Ovamboland

|

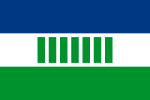

Ovamboland Ovambo |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Capital | Ondangua |

| size | 56,072 km² |

| Residents | 239,363 (1960) |

| Form of government | Homeland |

| Head of state |

|

| founding | 1968 (1973 autonomy) |

| resolution | May 1989 (before Namibia's independence ) |

| currency | South African rand |

| license plate | SWA |

|

Location of the former homeland Okavangoland |

|

The Ovamboland (also Owamboland , formerly Amboland ), as homeland since 1972 or 1973 only Owambo (or Ovambo ) is the historical name for a geographical area in Namibia (formerly South West Africa ) and home of the Ovambo people . The term comes from the German colonial times and the time of the South African occupation, but is used today almost without exception by the Ovambo themselves as well as by all other ethnic groups in Namibia.

From 1968 to 1990 Ovamboland was a homeland based on the South African model, and since 1973 an autonomously administered homeland with around 239,000 inhabitants.

The veterinary fence of Namibia , which, from an agricultural point of view, separates the north of the country from the south in order to contain animal diseases that are common in the north, is often regarded as the southern border of Ovamboland. The city of Oshivelo , located in southern Ovamboland and on the most important north-south connection , is now considered the "gateway to Ovamboland".

A special scenic feature of Ovamboland is the large number of Makalani palms ( Hyphaene petersiana ) growing there . In addition, the largely communal land use without fenced farms or pastures represents a strong contrast to the rest of Namibia.

history

Settlement, Colonial Era and Apartheid

The area southwest of the Okavango and north of the Etosha pan was settled by the Ovambo between the 15th and 16th centuries. Since the Ovambo also farmed agriculture in addition to cattle , they were relatively sedentary from the start. It was not until the 19th century that the first Europeans penetrated the Ovambo settlement area . Francis Galton , Karl Johan Andersson and Carl Hugo Hahn were among the first . They were soon followed by missionaries who started their work in Ovamboland. A little later, traders followed , who mainly bought ivory and ostrich products in exchange for weapons , ammunition , clothing or horses .

During the German colonial period in what is now Namibia, as well as the simultaneous Portuguese rule in neighboring Angola , the local rulers of the Ovambo began to make their subjects available to the colonial rulers as workers for a limited period in exchange for bonuses. These were mostly young men who were then placed in the service of the Germans or the Portuguese for a few years.

In 1897 there was a strong outbreak of rinderpest in Ovamboland as a result of which around 90% of all cattle in the region perished. A very long period of drought that occurred around the same time led to the almost complete collapse of the Ovamboland economy .

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the German colonial power set up some checkpoints on the southern border of the area, in particular to monitor the movement of cattle to and from the region. The Germans never took any serious steps to bring Ovamboland under their complete control, let alone colonize it. Only Major Franke made a few trips to the region after the Herero Wars. Only in 1908 were official protection treaties concluded with the Ovambo kings.

After German South West Africa was conquered by the South African Union in the First World War in 1915 , the South African occupiers initially limited themselves to patrols in the Ovambo area.

The attitude of South Africa towards Ovamboland was to change fundamentally in 1916, when the Kwanyama king Mandume Ndemufayo remained victorious in the fight against the Portuguese in neighboring Angola, captured numerous weapons and then managed himself again with the booty in what is now Namibian (and then South African ) Withdrew part of Ovamboland, which was viewed as a threat by the South Africans. Ndemufayo was given an ultimatum to voluntarily bow to the South African occupying power . After the hoped-for effect could not be achieved in this way, the South African Union Defense Force dispatched more than 800 soldiers to Ovamboland in February 1917, who defeated the Kwanyama. Ndemufayo was killed in the process.

The then commander of the British-South African military administration, Colonel de Jager , appointed himself King of the Ovambo after the campaign . The Ovambo were then disarmed and sent in large numbers to the south as "contract workers".

In 1919 South West Africa was taken over as a mandate area by the Union of South Africa on behalf of the League of Nations . In the following decades the restrictions and controls in Ovamboland were steadily expanded, which reached its peak in 1964 in the course of the apartheid policy .

The first regionally effective step for Ovamboland in the course of the homeland formation in South West Africa proposed by the Odendaal Commission was Proclamation R 291, which came into force on October 2, 1968 by the South African President . Herewith the establishment of the Ovamboland Legislative Council , a self-governing body, was ordered. With the proclamation R 290 issued on the same day, seven traditional tribal authorities were appointed . These were the tribal authorities of Kolonkadhi-Eunda, Kwaluudhi, Kwambi, Kwanyama, Mbalantu, Ndonga and Ngandjera. The formal legal basis for these steps was the Development of Self-Government for Native Nations of South-West Africa Act ( Act 54/1968 ), passed in the same year , which, according to the South African government, “realizes its right to self-determined development in in an orderly way to a self-governing nation and independence ”for the people of Ovamboland.

Through the Proclamation R 104 of April 27, 1973 ( Owambo Constitution Proclamation ), the South African administration introduced self-government status in the District of Ovamboland . The name was changed to Owambo and Ongwediva was established as the seat of the administration and Ndonga , English and Afrikaans were declared official languages . The highest representative body of the local population was the Owambo Legislative Council (German: "Legislative Assembly of Owambo"), whose first election took place in 1973 and as a result of which the apartheid-supporting chief Filemon Elifas was elected Chief Minister .

Namibian Liberation Struggle

No other region in Namibia was so dominated by the Namibian liberation struggle as Ovamboland. The was SWAPO driving. SWAPO itself emerged from the OPO , a pure Ovambo party .

During the Namibian liberation struggle, thousands of Ovambo lost their lives and tens of thousands had to flee into exile . In the period from 1975 to 1988 alone, around 50,000 Ovambo fled to Angola. As a consequence, among other things, the further development of Ovamboland continued to decline significantly during these years.

The first military confrontation between the Ovambo and the South African armed forces took place in Ongulumbashe in 1966 and until the end of a decades-long conflict that ended with the independence of Namibia, most of the fighting between the PLAN (the armed arm of the SWAPO) and the South African armed forces took place in Ovamboland instead.

One of the most prominent victims of this armed conflict was the Chief Minister of the Homeland Filemon Elifas. He was killed on the evening of August 17, 1975 as a result of a guerrilla attack on his car near Ondangwa . Elfias died on the way to an infirmary and the assassins escaped. The unrest was marked by attacks on African tribal representatives and trade institutions as well as the use of land mines . Most of the incidents were attributed to SWAPO.

administration

On the Namibian side (formerly German name: Südliches Amboland ), Ovamboland is now divided into the following four regions :

literature

- John Paul : Economy and Settlement in southern Amboland. In: Scientific publications of the Museum for Regional Geography in Leipzig. NF 2. 1933 (with references).

- Johannes Paul: German South West Africa. In: Carl Petersen, Otto Scheel, Paul Hermann Ruth, Hans Schwalm (eds.): Concise Dictionary of Border and Abroad German , Volume II. Ferdinand Hirt Verlag, Breslau 1936, pp. 262–278 (pdf, 4.1 MB).

- Joachim Fernau, Kurt Kayser, Johannes Paul (Eds.): Africa is waiting. A picture book on colonial politics. Rütten & Loening Verlag, Potsdam 1942. (With photographs by Johannes Paul from the geographical research trip 1928–1929 to Ovamboland)

- Nick Santross, Gordon Baker, Sebastian Ballard: Namibia Handbook . 3. Edition. Footprint Handbooks, Bath (England) 2001, ISBN 1-900949-91-1 , pp. 177 ff.

- Heinrich Vedder: South West Africa's history up to the death of Maharero in 1890. 1st part. Namaland and Hereroland, Amboland . Chapter 1. Discovery and Exploration . SWA Scientific Society, Windhoek 1973, pp. 18–40.

Web links

- Amboland. In: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon , Volume 1. 1920, pp. 38–39 .

- Sorghum. In: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon, Volume 3. 1920, pp. 375–376 .

- Andersson, Karl Johan. In: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon, Volume 1. 1920, p. 50 .

- Dag Henrichsen: Classifying Colonial Territory and Mapping out an Academic Career. The Example of Hans Schinz, Botanist in Southwestern Africa and Zurich. (rtf, 22 kB) In: Imperial Culture in Countries without Colonies: Africa and Switzerland. October 23, 2003 (English).

- Namibia: Total Population Distribution 1995. In: MARA (Mapping Malaria Risk in Africa). February 15, 2002, archived from the original on September 26, 2007 ; accessed on October 20, 2018 (English).

Individual evidence

- ^ Gregor Dobler: Traders and Trade in Colonial Ovamboland, 1925–1990 Basler Afrika Biographien, Basel 2014, ISBN 978-3-905758-40-5 , p. 89.

- ^ A b André du Pisani : SWA / Namibia: The Politics of Continuity and Change . Jonathan Ball Publishers , Johannesburg 1985, ISBN 978-08685-009-28 , pp. 229-230

- ^ A b President van die Republiek van Suid-Afrika: Proklamasies No. R 138, 1976: Wysiging van die Owambo-Grondwet-Proklamasie, 1973 (Amendment of the Owambo Constitution Proclamation 1973). (pdf, 1.6 MB) In: Staatskoerant van die Republiek van Suid-Afrika, Regulasiekoerant No. 2344. July 30, 1976, pp. 1–2 , accessed October 20, 2018 (Afrikaans, English).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Livia and Peter Pack: Namibia. DuMont, Cologne, 2nd edition, 2004, ISBN 3-7701-6137-8 .

- ^ SAIRR : A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1968 . Johannesburg 1969, p. 309

- ^ SAIRR: A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1968 . Johannesburg 1969, p. 307

- ^ SAIRR: A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1973 . Johannesburg 1974, pp. 388-389

- ^ SAIRR: A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1975 . Johannesburg 1976, pp. 347-348

- ^ SAIRR: A Survey of Race Relations in South Africa 1976 . Johannesburg 1977, p. 479