German South West Africa

|

German South West Africa (then South West Africa ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Capital : | Berlin , German Empire | ||||

| Administrative headquarters: | 1885–1891: Otjimbingwe 1891–1915: Windhoek 1915: Grootfontein |

||||

| Administrative organization: | 5–12 districts | ||||

| Head of the colony: | 1884–1888: Kaiser Wilhelm I. 1888: Kaiser Friedrich III. 1888 - Surrender on July 9, 1915: Kaiser Wilhelm II. |

||||

| Colony Governor: | look here | ||||

| Residents: | approx. 200,000 inhabitants, including approx. 12,500 Germans (1913) | ||||

| Currency: | Gold mark | ||||

| Takeover: | 1884-1915 | ||||

| Today's areas: |

Namibia and the southern edge of the Caprivi Strip in Botswana |

||||

German South West Africa was a German colony (also a protected area ) from 1884 to 1915 on the territory of what is now the state of Namibia . With an area of 835,100 km², it was about one and a half times the size of the German Empire . German South West Africa was the only one of the German colonies in which a significant number of German settlers settled. During the First World War , the area was conquered by troops of the South African Union in 1915 , placed under its military administration and in 1919 transferred to the administration of South Africa as a League of Nations mandate of South West Africa in accordance with the provisions of the Versailles Peace Treaty .

population

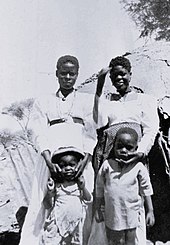

The country was never densely populated; because apart from a few exceptions it could only be used by extensive cattle breeding . There was no uniform population in the former colony area. Especially in the area of the largest elevations in the highlands, near Windhoek, the two main peoples Herero and Nama bordered each other at the time of the German occupation . In addition, there were the San , who were excellently adapted to the adverse living conditions , the enslaved Damara and the farming Owambo , who lived in the far north .

Before the occupation by Germany, around 80,000 Herero , 60,000 Owambo , 35,000 Damara and 20,000 Nama lived in South West Africa . German South West Africa was the only German colony in which a targeted settlement of Germans took place on a large scale ( settlement colony ). In addition to the mining of lead , copper and zinc ores (at Otavi-Tsumeb since 1901) and diamonds (since 1908), it was in particular cattle breeding that attracted German settlers to the country. In 1902 the colony had around 200,000 inhabitants, including 2595 Germans , 1354 Boers and 452 British. Another 9,000 German settlers were added by 1914.

history

prehistory

South West Africa entered the area of European research and knowledge only late. In the 15th century (1486) the Portuguese had left landing signs in the form of crosses on their India voyages, but it was only the assumption that wealth could be acquired inside that led to several expeditions from the Cape in the 18th century . They should find out how the fabulous wealth of cattle of the Herero could be transformed into tinkling coins and whether there might not be gold deposits in the country. However, both intentions were just as unpromising as a later attempt by the British to set up a copper mine.

As early as 1868, German missionaries from the Rhenish Mission Society wanted the King of Prussia to be interested in the area and asked for his protection, as they had to suffer a lot from the constant struggles of the Africans. However, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 let these efforts fall into oblivion. In 1876 the British tried to take possession of the area from the Cape Colony , but could not prevail. However, they kept the whale bay and the penguin islands in their hands. When inland Europeans, missionaries and traders complained of a lack of protection due to alleged attacks by Africans, the British colonial authorities declared that they had nothing to do with the interior of the country and that they had no administration. The British, as they themselves declared, made no further claims on South West Africa.

Taking possession

On May 1, 1883 , the 22-year-old merchant's assistant Heinrich Vogelsang acquired the Bay of Angra Pequena, today's Lüderitz Bay and five miles of hinterland from the Nama people in Bethanien, on behalf of the Bremen tobacco dealer Adolf Lüderitz . The purchase price agreed with their captain Joseph Frederiks was 200 old rifles and 100 English pounds. In September 1883 Lüderitz sailed on board a three-master to South West Africa to inspect his acquisitions as the new sovereign. He was soon celebrated in the newspapers as a hero of the German colonial movement. Chancellor Bismarck sent the gunboat SMS Nautilus on a reconnaissance trip into Lüderitz Bay. Its captain Karl Ascheborn later reported to the Chancellor in writing and stated that he had found that Lüderitz had initially only measured the land in English miles . This length measure, which is also well known to the Nama, was not expressly agreed in the contract, so that the four times longer geographic German mile was to be expected. Lüderitz took up the idea immediately and from then on claimed an area sixteen times larger. The Nama felt deceived, but could not get their point across despite protests. On April 24, 1884, Bismarck telegraphed the German consul in Cape Town that “ Lüderitzland ” was under the protection of the German Empire . The land acquisitions by the Bremen merchant had rekindled the interest of Great Britain and the Cape in this area. However, after Bismarck appeared so determined and the British legal claims had to appear questionable after having previously given up the area, they had no choice but to give in. They only claimed Walvis Bay, which was occupied earlier. In return, Germany finally dropped its claim to the South African bay of Santa Lucia in November 1884 in favor of Great Britain.

The first official flag-raising in South West Africa took place on August 7, 1884 with the participation of the Nama captain Josef Fredericks II and his councilors, the crews of two German warships, the cruiser frigate Leipzig and the corvette Elisabeth , and representatives of the Lüderitz company at Fort Vogelsang in Lüderitzbucht instead of.

Extensions

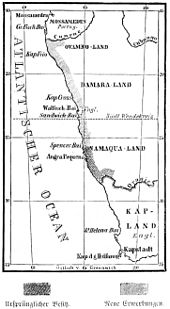

That same month, Vogelsang signed a second contract in which Lüderitz, the coastal strip between the Orange River and the 26th parallel, and an area 20 miles inland from any point on the coast, was sold for an additional £ 500 and 60 rifles. In 1885 the first administrative headquarters were established in Otjimbingwe . By 1890, Deutsch-Südwest expanded to include Damaraland , Ovamboland and the Republic of Upingtonia in the north. In the northeast, the Caprivi Strip was added, which promised new trade routes and which established the connection to the Zambezi River . This area was based on the profit with the UK concluded Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty from 1 July 1890th

German South West Africa then extended from the Orange River, the border against the Cape in the south, for more than 1200 km to the Kunene, the border river against the Portuguese Angola in the north. Its width from the coast inland fluctuated, apart from the “Caprivi Strip”, between around 450 km in the south and almost 1000 km in the north. On October 18 of the same year, at the instigation of Captain Curt von François, the foundation stone was laid for the “Great Windhoek” festival. The sanctuary administration was moved to this fortress soon after. The later regional capital Windhoek , which is officially called "Windhoek" today , was built around it over the next few years .

Colonial administration until 1903

After Lüderitz had convinced the German government of the economic importance of his branch in South West Africa and urgently asked for sovereign protection, Gustav Nachtigal was appointed Imperial Consul General and Commissioner for German West Africa in 1884 . In the era of his short term in office, the protection treaty was concluded with the Nama. After Nachtigal's death, Chancellor Bismarck appointed Heinrich Göring , the father of the later National Socialist politician Hermann Göring , as the new Reich Commissioner in 1885 . This concluded further protection treaties with the local tribes. He was assisted by Carl Gotthilf Büttner as a further negotiator as well as the former court trainee Louis Nels , who was acting as "Chancellor", and Sergeant Goldammer, who was supposed to exercise police powers.

In 1887 it was rumored that gold had been found near Walvis Bay. Goering was then asked to request a protection force from the Reich to maintain order in the supposed gold fields. The Reich government rejected the request, pointing out that the affected area was privately owned by the German Colonial Society . With the support of Göring, the colonial society then set up its own mercenary troop, consisting of two officers, five non-commissioned officers and 20 black soldiers. The gold discovery later turned out to be a hoax, and the Schutztruppe disbanded after having previously only been noticed by their lack of discipline.

In 1888 there were disputes between the Witbooi tribe and the Herero, who hoped in vain for support from the Germans. The Herero then terminated the mining rights of the Germans and the protection treaty. Goering succeeded neither in reversing the terminations of the contract nor in pacifying the fighting tribes. When the Witbooi also began to terrorize the whole country with looting, Göring and the entire German administration, escaping the chaos, withdrew to the British Walvis Bay.

At the insistence of the colonial society, in May 1889, the imperial government sent a troop of 21 under the leadership of Lieutenant Hugo von François , which was later expanded to 50 men to reinstate the German administration and to pacify the country. François cut off the arms supply to the Herero and built Windhoek into a fortress. Impressed by the energetic demeanor, the Herero withdrew the termination of the protection treaty in 1890. In the same year Göring returned to Germany, and François was appointed provisional Reichskommissar and provincial governor on May 12, 1891. Civil and military power were thus in one hand. François saw it as his most important task to push back the Witbooi under their captain Hendrik Witbooi , because they now increasingly attacked the German settlers. After the protection force had been increased again to now 212 soldiers and two officers, François took up the fight against the Witbooi in April 1893. After the battle of Hornkranz , Hendrik Witbooi withdrew to the impassable Naukluft Mountains and waged a guerrilla war against the Germans.

When François had still not defeated the Witbooi after six months and barely performed his duties as governor, resentment arose in both South West Africa and Germany. The Reich government sent Major Theodor Leutwein to Africa in December 1893, initially with the order to support François in his administrative tasks. But both quickly worked together militarily. After they had succeeded in establishing a number of military stations in the Witbooi area, François resigned his offices and returned to Germany. Leutwein was now faced with the task of ending the fight against the Witbooi under their captain Hendrik Witbooi, who had meanwhile holed up in the Naukluft, an inaccessible rocky landscape. After the German troops had been reinforced by supplies from Germany, Leutwein attacked the Witbooi on August 27, 1894 with three companies and forced them to surrender on September 11, 1894 after grueling battles for both sides. A protection contract was concluded with Captain Hendrik Witbooi, which guaranteed his tribe their own settlement area, which, however, was supposed to be under the supervision of a German garrison. The Witbooi kept to this treaty until the outbreak of the Herero uprising. After Leutwein subsequently succeeded in pacifying the Herero tribes, apart from minor skirmishes, calm returned to German South West Africa for almost ten years. In the 1890s, German settlers (e.g. Gustav Voigts ) took over farmland. In 1898 Leutwein was appointed governor of the colony.

The Herero uprising

The Herero uprising under their captain Samuel Maharero began on January 12th, 1904, after the ethnic group saw itself more and more pushed back from their settlement area by massive land purchases by the German Colonial Society and they had been brought to the brink of economic existence by unscrupulous traders. Initially, individual farms, railway lines and trading posts were attacked. There was fierce fighting over the city of Okahandja . The initially outnumbered German protection force was reinforced in February by 500 marines and a volunteer force. The fight against the Herero was started with three divisions. Since Leutwein misjudged the fighting strength of the Herero, it was initially not possible to gain decisive advantages. The Reich government was dissatisfied with the course of the operations and appointed Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha as the new commander in chief of the Schutztruppe . In contrast to Leutwein, von Trotha's aim was to destroy the enemy completely. He had reinforcements come from Germany again and put the Herero on August 11, 1904 for the decisive battle at Waterberg .

The Herero managed to evade to the southeast, as planned in the event of a defeat, but they underestimated the difficulties that arose from fleeing through the Omaheke dry savannah with herds of cattle and goats, children and the wounded . According to various sources, up to 60 percent of the Herero were killed during the fighting and the flight. This went down in history as the genocide of the Herero and Nama .

In October 1904 the Nama rose in the south of the country. The apostate Captain Hendrik Witbooi had the friendly district administrator of Gibeon von Burgsdorff killed. At the same time, Captain Jakob Morenga rose and intervened in the fighting. Years of grueling guerrilla warfare with the Schutztruppe followed, which was not finally put down until 1907/08. The events cost the lives of between 24,000 and 64,000 Herero, around 10,000 Nama and 1,365 settlers and soldiers, according to estimates , through illness, hunger and thirst, fighting, raids, flight and in many cases inhumane abuses in the internment camps . 76 whites were considered missing and most likely died as a result of the war.

Peace period 1908 to 1914

The uprisings almost brought the economy of German South West Africa to a standstill, the farm economy had to be completely rebuilt, there were hardly any cattle left. The reconstruction had already been initiated by the new governor Friedrich von Lindequist , appointed on November 19, 1905 . With compensation totaling 7 million Reichsmarks, the Reich government ensured that most of the farmers could be kept in the country.

In 1908 Bruno von Schuckmann became the new governor. He made sure that aid was distributed effectively, put an end to land speculation and encouraged the importation of livestock. The importation of karakul sheep , whose skin and meat could be marketed excellently, was very beneficial for the South West African economy . The opening of the Lüderitzbucht – Keetmanshoop railway line in July 1908 also helped promote economic activity.

At the urging of the white population, on January 28, 1909, the imperial government issued an ordinance on self-government in German South West Africa, with which community and district associations and a regional council were brought into being. The National Council, which met for the first time in April 1910, had the task of advising the governor, who continued to head the colonial administration.

Germany tried to attract orphans as low-wage assistants for business people and tradespeople. The young people destined for German South West Africa were only to be accommodated with those colonists who appeared trustworthy and who left nothing to be missing "in the moral and professional training" of their wards. Priority was given to young people and girls released from orphanages, under no circumstances those from reform schools and so-called rescue houses.

In June 1908 the first diamond was found east of Lüderitz, which triggered a mass rush to the area and gave the country a new branch of industry, diamond mining. After just three months, diamonds totaling 2,720 carats had been found, and by the end of the year the value of the extraction was already 1.1 million Reichsmarks. Until the outbreak of the First World War, diamonds worth 152 million Reichsmarks were mined. Much to the displeasure of the population, the Reich Colonial Office blocked the area of the diamond fields south of the 26th parallel to the Orange River in a width of 100 kilometers and granted the sole mining rights to the landowner, the German Colonial Society. From 1912 diamond mining was subject to a tax of 6.6 percent, whereby the colonial administration received about 10 million Reichsmarks annually.

First World War and the end of the colony

The news of the outbreak of the First World War reached German South West Africa on August 2nd via the large radio station in Windhoek, which is still under construction . With the outbreak of war, an attack by the South African Union, allied with Great Britain, was expected in German South West Africa . Therefore, on August 8, the mobilization was called and a 50 km wide strip along the border with South Africa was evacuated. On September 9, the South African parliament decided to participate in the war.

The first shots were fired at the police stations of Nakop and Ramansdrift on September 13, 1914 , and on September 19, 2000-strong South African troops occupied Lüderitz Bay. A day later, a division of the Union troops crossed the Orange River, but they were repulsed by the German troops in the Battle of Sandfontein . The South Africans then relocated their attacks to Lüderitz Bay and were able to advance 70 kilometers inland along the railway line by November 9. In March 1915, South African troops marched from Walvis Bay towards Keetmanshoop , which fell into their hands on April 19. In the south, the German protection force had to give way to the superior strength of the enemy and withdrew to the north. At the beginning of May, Governor Theodor Seitz moved his official residence from Windhoek to Grootfontein .

It now turned out that the German protection force was hopelessly inferior to the South Africans; this applied to both troop strength and equipment. While the German troops had been increased to 5,000 men by seamen, reservists, volunteers and locals when the war broke out, they faced an army of 43,000 soldiers on the opposing side. The Germans had two obsolete aircraft and five motor vehicles at their disposal, while the South Africans were able to use six modern combat aircraft and 2,000 motor vehicles.

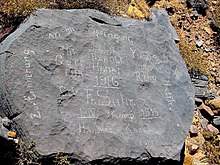

After the Union troops had pushed the German defenders further and further back, also in the north, Governor Seitz offered the South African General Botha an armistice on May 21, 1915 in vain. On July 1, the Schutztruppe suffered their final and final defeat in a battle near Otavi , west of Grootfontein. On July 9, 1915, Governor Seitz and Lieutenant Colonel Victor Franke signed a declaration on the handover of the German protection force to the South African Union.

The active part of the protection force was interned in a camp near Aus , the reservists were able to return to Germany. The South African military took over the administration of the German colony. About half of the German population in South West Africa had been sent back to Germany by July 1919. The end of German South West Africa was sealed with the Versailles Treaty of June 28, 1919. It was declared a mandate area of the League of Nations and named South West Africa under the administration of the South African Union .

Economy and Infrastructure

Agriculture

The first German settlers were mainly concerned with livestock farming. The number of cattle kept rose from around 121,000 in 1910 to 205,000 three years later.

In the south, wool sheep and goat breeding developed. Goats and sheep have always been widespread in the country and primarily provided meat food. European breeders experimented with merino and karakul sheep , the numbers of which grew rapidly. Of the 135,500 km² of usable agricultural area, only 56 km² were built on in 1913 - mostly with maize, potatoes or pumpkins. The planned expansion of irrigated areas no longer took place due to the war.

Mining

Mineral resources were found in German South West Africa even before diamonds were found. However, the hope that was cherished early on that gold would be minable did not come true. Instead, the mining of copper ores came second after diamonds. Copper was mined mainly at Tsumeb and Otavi and at the Khan-Rivier . A marble factory was built in the area around Karibib and marble was prepared for shipment to Germany.

Indigenous labor

Indigenous workers, mostly from Ovamboland, were recruited on the farms, and farmers who treated their indigenous workers badly often had difficulties recruiting. Hereros and Bushmen could hardly be used for work in the western sense. The natives control measures of 1907 led many natives to take up wage-related employment. For railway construction, people from South Africa preferred to recruit " Kaffirs " and Baster . After some of the 6,500 workers went on strike in Wilhelmsthal in 1911, they were supposed to be replaced. However, the administrations of the other German colonies in Africa rejected requests for workers. In 1913, the Provincial Council ruled that the few seasonal workers from Ovambo were only allowed to be used in railroad and mining. In 1915 the British occupiers estimated the number of potentially recruited workers at 156,000.

Traffic routes

When copper was found in the north and then diamonds in the south, a local industrial infrastructure also developed.

The construction of the first railway line from Swakopmund to Windhoek , with a gauge of 600 millimeters, began in 1897. The previously exclusively available ox wagons had been criticized for a long time as inadequate and too slow, but the outbreak of rinderpest had brought the transport system to a collapse that year. The full route was opened on July 19, 1902. From 1903, the Otavi Mining and Railway Company (OMEG) also built a line from Swakopmund with the Otavibahn , which ran parallel to the state line to Windhoek to Kranzberg . In Otavi, the route branched out to the endpoints Tsumeb and Grootfontein. With the route, OMEG opened up the abundant copper deposits around Otavi. In the 1950s it was replaced by a cape gauge line.

Until the end of German colonial rule in 1915, further rail connections followed to the south and north of the country; so from Lüderitz to Aus and Keetmanshoop (1908) and from Keetmanshoop to Windhoek. These routes were created in Cape Gauge, analogous to the neighboring South African Union . The section between Windhoek and Kranzberg of the first state railway was also converted to Cape Gauge in 1910 (the remaining section to Swakopmund was only changed by the British during the First World War). This gave German South West Africa the most extensive route network of all German colonies. At the outbreak of World War I, it had a length of 2372 kilometers, of which 2178 km were in operation. With the construction of this railway network, a decisive share in the rise of the country was achieved. The early, state-supported attempt to open up the country with trucks was unsuccessful with two imported models, as they got stuck in the desert sand.

The automobile also remained a marginal phenomenon in the colony. In 1909, the government introduced the first car, a Daimler-Benz Mercedes. In the same year, the German officer Paul Graetz, at the end of his Africa crossing, drove through the area of German South West Africa, coming from the east, via Windhoek to Swakopmund. In general, until the end of German colonial rule, it was left with the ox-drawn carts, which the military also used.

A regular ship connection with Germany took place from 1898 on the 25th of each month through the Woermann Line . Until the completion of a jetty (planned for 1915) in Swakopmund, this was given a transport monopoly that also applied to Lüderitz. A ship connection between Cape Town and Walvis Bay was served by the coastal steamer "Leutwein". The colony was visited almost exclusively by ships sailing under the German flag. Foreign ships accounted for 15% of the tonnage in 1907 and only 2.4% in 1912.

Post and telecommunications

By 1913, 102 post and telegraph companies had been established in German South West Africa. The number of postal workers rose from 13 in 1902 to 73 by April 1913, plus 91 natives in subordinate positions. The operation of smaller postal agencies (1913: 42) was often taken care of by railway officials or police officers, etc.

From 1901 heliograph routes were set up in German South West Africa . They reached far in the north and south of the country as well as in the east to Gobabis . These were used militarily as well as civilly.

The telegraph lines were operated by the post office, the railroad or the military. The civil network at that time had a total length of 3964 kilometers. By April 1913, local telephone networks with 954 lines had been set up at 28 locations. At Walvis Bay, the sanctuary was connected to the world telegraph network via a British submarine cable . After 1910 plans for the use of radio stations in German South West Africa began to take shape. On February 4, 1912, the Swakopmund coastal radio station went into operation. A similar station in Lüderitzbucht was completed on June 3, 1912. Shortly before the beginning of the First World War, the Windhoek radio station was finally set up. The station was comparable to the Kamina radio station in Togo , which was intended as a switching point to Germany. As an experiment, the direct connection with the major radio station in Nauen near Berlin, 8,340 kilometers away, also succeeded .

Administration of justice

The administration of justice vis-à-vis the German population and the Europeans who were treated as “fellow protectors” was carried out by district courts and the higher court in Windhoek. District courts existed in Keetmannshoop, Lüderitz, Omaruru, Swakopmund and Windhoek in 1909.

Until the uprisings of 1904–1908, the tribal chiefs were largely still entrusted with the administration of criminal justice towards the indigenous population. As far as possible autonomy in jurisprudence was guaranteed by the protection treaties . After the end of the uprisings, the contractually guaranteed autonomy was deemed “forfeited”, so that the indigenous population was fully under the jurisdiction of the district officials, i.e. the heads of the individual administrative districts. Only the tribes not involved in the uprisings were left with jurisdiction in civil disputes. In 1914 there were eleven district offices, five independent district offices and one residency that were entrusted with the administration of indigenous justice.

Banks

A substantial part of the intra-colonial money transactions was carried out through postal orders. Mark banknotes that had not been issued by the Reichsbank were only accepted at high discounts. Before 1914 the Deutsche Afrika Bank (head office Hamburg) operated as a commercial bank u. a. in Lüderitz . The German Colonial Society brokered banking transactions to Swakopmund through its Berlin headquarters. A German-South West African cooperative bank was founded in 1908 in Windhoek by 28 farmers. In 1912 there were 131 members of the cooperative. The Swakopmund Bank Corporation, founded by industrial workers in 1911, was also organized as a cooperative . Its membership rose from 56 to 68 between 1911 and 1912, with a profit sharing of 21%. The savings and loan fund (Gibeon) , which had 44 members in 1913, was only of local importance, where the warehouse was also operated. The South West African Boden-Kredit-Gesellschaft (founded in Swakopmund in 1912), capitalized with one million marks, was the first credit institution in the colony to provide all financial services of a commercial bank. During the short period of its existence, it mainly served as a house bank for the municipal administrations and a mortgage fund. Branches were opened in Lüderitz and Windhoek. Already in the first year a loan of 3 million marks was issued. The ten million marks in capital of the land bank , which was brought into being by an imperial decree of June 9, 1913, were to be raised entirely by the protectorate administration. The purpose of the business was to provide low-interest loans for the expansion of agriculture and infrastructure. It completely controlled the business of Omaruru Bank , founded on private initiative in December 1913 , whose 100 shareholders each had to subscribe at least 5000 marks.

Soon after the occupation in 1915, the banking operations were taken over by the Standard Bank of South Africa and the First National Bank of South Africa .

aviation

As early as the Herero and Nama uprising , the German side used telegraph departments for the airship troops . The military raised antennas with small tethered balloons to extend the range of the radio signals. In May 1912 the German-South West African Aviation Association was formed in Keetmanshoop . Numerous local groups subsequently emerged, including in Lüderitzbucht, Swakopmund and Windhoek. The number of members grew to several hundred. The aim of the association was to promote aviation in the German colonies, especially in German South West Africa. The focus was on the demand for airplanes and airships for military purposes. The idea met with approval from the competent authorities in the colonial administration, so that in 1914 one aircraft each was stationed at the airfields at Karibib and Keetmanshoop. This is also where the protection force's trains were located . Airfields were also created with simple means in other places in the protected area. In May and June 1914 a total of three aircraft arrived in Swakopmund by ship . It was an aviation - as well as a Roland arrow biplane from LFG . On a private initiative , the pilot Bruno Büchner undertook postal and inspection flights with a third aircraft, a Pfalz double-decker with a pusher propeller , before he embarked with his aircraft on to German East Africa . The other two aircraft were used for reconnaissance flights and bombing of enemy troop camps in South West Africa during World War I until they were lost in unsuccessful take-offs in April and May 1915.

Planned symbols for German South West Africa

In 1914, a coat of arms and a flag for German South West Africa were planned, but were no longer introduced because of the outbreak of war.

See also

- German language in Namibia

- German colonial efforts in Southeast Africa

- The other side of silence , novel by André Brink

- The German Empire - Storm over Southwest , TV documentary from 2010

literature

- Dirk Bittner: Great Illustrated History of South West Africa . Melchior Verlag, 2012, ISBN 978-3-942562-79-9 .

- Imre Josef Demhardt: The cartography of the protected and mandate area South West Africa . In: Cartographica Helvetica. Issue 30, 2004, pp. 43-52.

- Udo Kaulich: History of the former colony of German South West Africa. An overall picture. 2nd, corrected edition. Lang, Frankfurt 2003, ISBN 3-631-50196-X .

- German Colonial Society: Small German Colonial Atlas. Publishing house Dietrich Reimer, Berlin 1899.

- Christoph Marx: History of Africa: from 1800 to the present. UTB, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8252-2566-6 .

- Johannes Paul : Germans, Boers and English in South West Africa. Accompanying word to a map of nationalities of Europeans in South West Africa. In: Koloniale Rundschau. 9/10, 1931.

- John Paul: Economy and Settlement in southern Amboland . In: Scientific publications of the Museum for Regional Geography in Leipzig. NF 2, 1933 (with references)

- Johannes Paul: German South West Africa . (PDF; 4.3 MB). In: Concise dictionary of border and foreign Germans. Volume II (Eds.): Carl Petersen, Otto Scheel, Paul Hermann Ruth and Hans Schwalm. Ferdinand Hirt Verlag, Breslau 1936, pp. 262-278.

- GW Prothero (Ed.): South-West Africa. (= Handbooks prepared under the direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office . No. 112). London 1920.

- H. Rafalski: From no man's land to an orderly state: history d. former Kaiserl. State Police for German South West Africa; to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the founding day on March 1, 1930. Wernitz, Berlin 1930, DNB 576335649 .

- Helmut Rücker, Gerhard Ziegenfuß: A skull from Namibia - head held high back to Africa . Anno-Verlag , Ahlen 2018, ISBN 978-3-939256-75-5 .

- Wilhelm R. Schmidt : Otto Schiffbauer. As a telegraph builder in German Southwest . Sutton, Erfurt 2006, ISBN 3-89702-992-8 .

- Heinrich Schnee (Ed.): German Colonial Lexicon. (Enter "South West Africa"). Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920. (3 volumes)

- Julian Steinkröger: Criminal law and the administration of criminal justice in the German colonies: A comparison of law within the possessions of the empire overseas. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-339-11274-3 .

- Jürgen Zimmerer: German rule over Africans. State claim to power and reality in colonial Namibia . Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5047-1 .

- Joachim Zeller, Jürgen Zimmerer (eds.): Genocide in German South West Africa: the colonial war (1904–1908) in Namibia and its consequences. Christoph Links, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-86153-303-0 .

Fiction representations

- Hans Grimm : South African short stories . Verlag Albert Langen, Frankfurt am Main 1913.

- Hans Grimm: People without space . Albert Langen publishing house. (First edition 1926)

- Uwe Timm : Morenga . Verlag Authors Edition, Munich 1978, ISBN 3-570-06415-8 . (dtv, 2004, ISBN 3-423-12725-2 )

- André Brink : The other side of the silence . Osburg Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-940731-07-4 .

- Gerhard Seyfried : Herero . Novel. Eichborn , Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-8218-0873-X . (with historical photographs and maps) (Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-7466-2026-0 )

- Gottreich Hubertus Mehnert : Short stories from South West Africa. 4th edition. Windhoek 2011, ISBN 978-99916-782-8-3 .

Web links

- The Colony of German South West Africa - German Historical Museum

- Zeit Wissen: Colonial history - German South West Africa becomes Namibia by Hellmuth Vensky, March 19, 2010

- Sebastian Dehnhardt, Ricarda Schlosshan: Storm over southwest. ( YouTube video) The German Empire (Part 2). (No longer available online.) ZDF , 2010, archived from the original on August 16, 2014 ; Retrieved October 11, 2011 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Lewis H. Gann, Peter Duignan: The rulers of German Africa, 1884-1914. Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, Cal. 1977, ISBN 0-8047-0938-6 , p. 7.

- ^ History. Klaus Dierks . Accessed July 31, 2020.

- ↑ Santa Lucīa. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon. Volume 17, Leipzig 1909, p. 587.

- ^ G Dornseif: Orphan import and maid recruitment for Southwest. ( Memento from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) In: Windhuker Nachrichten. September 1908.

- ↑ The Farmer. In: Windhoek News. Windhoek September 8, 1908.

- ↑ German Colonial Atlas with Yearbook 1918 - The War in German South West Africa .

- ^ GW Prothero (ed.); South-West Africa. (= Handbooks prepared under the direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office. No. 112). London 1920, pp. 48-9.

- ^ German South West Africa (section "Bergwesen") , in: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon. Volume I, Leipzig 1920, p. 410 ff.

- ↑ Government Ordinance No. 82 of Aug. 18, 1907. The provisions (compulsory passport against vagabonding etc.) read as strict from today's perspective, but hardly differed from analogous contemporary regulations of other colonial powers.

- ^ GW Prothero (ed.); South-West Africa. (= Handbooks prepared under the direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office. No. 112). London 1920, p. 42f.

- ^ Hans Emil Lenssen: Chronicle of German South West Africa 1883-1915. 7th edition, Namibia Scientific Society, Windhoek 2002, ISBN 3-933117-51-8 , p. 202.

- ↑ Paul Graetz: In the car across Africa . Braunbeck & Gutenberg, Berlin 1910. (Reprint: Klaus Hess Verlag, Göttingen / Windhoek 2007, ISBN 978-3-933117-35-9 .)

- ^ Hans-Otto Meissner: Dreamland Southwest. European book u. Phonoklub, Stuttgart 1969, pp. 235-258.

- ^ German South West Africa : Transportation. In: German Colonial Lexicon . 1920. (on: ub.bildarchiv-dkg.uni-frankfurt.de ).

- ^ Image of the radio station Swakopmund , Colonial Image Archive, University Library Frankfurt am Main.

- ↑ Reinhard Klein-Arendt: “Kamina calls Nauen!” The radio stations in the German colonies 1904–1918. 3. Edition. Wilhelm Herbst Verlag, Cologne 1999, ISBN 3-923925-58-1 , pp. 144ff. (The referenced distance of 9730 km is incorrect. Nauen-Windhoek are 8340 km)

- ↑ Julian Steinkröger: Criminal Law and Criminal Justice in the German colonies 1884-1914 A Comparative within the dominions of the Empire overseas . 1st edition. Publishing house Dr. Kovač , Hamburg 2019, ISBN 978-3-339-11274-3 , p. 253-256 .

- ^ GW Prothero (ed.); South-West Africa. (= Handbooks prepared under the direction of the Historical Section of the Foreign Office. No. 112). London 1920, pp. 101-107.

- ^ Karl-Dieter Seifert: German aviators over the colonies . VDM Heinz Nickel, Zweibrücken 2007, ISBN 978-3-86619-019-1 .