German East Africa

|

German East Africa (then Tanganyika and Ruanda-Urundi ) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Capital : | Berlin , German Empire | ||||

| Administrative headquarters: | 1885–1890: Bagamoyo 1890–1916: Dar es Salaam 1916: Tabora (provisional) |

||||

| Administrative organization: | 22 districts | ||||

| Head of the colony: | 1885–1888: Kaiser Wilhelm I. 1888: Kaiser Friedrich III. 1888–1918: Kaiser Wilhelm II. |

||||

| Colony Governor: | Hermann von Wissmann , Julius Freiherr von Soden , Friedrich von Schele , Hermann von Wissmann , Eduard von Liebert , Gustav Adolf von Götzen , Albrecht von Rechenberg , Heinrich Schnee | ||||

| Residents: | about 7.7 million inhabitants (1913), of which about 5300 are white, of which 4100 are Germans |

||||

| Currency: | 1890–1916: German-East African rupee | ||||

| Takeover: | 1885 - 1918 | ||||

| Today's areas: |

Tanzania (without Zanzibar ) Rwanda Burundi Kionga triangle in Mozambique |

||||

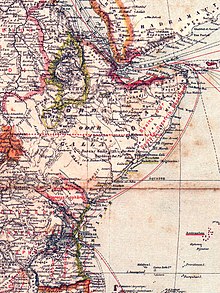

German East Africa was the name of a German colony (also a protected area ) that existed from 1885 to 1918 . The area comprised the present-day countries Tanzania (without Zanzibar ), Burundi and Rwanda as well as a small area in present-day Mozambique with a total area of 995,000 km² (almost double the area of the former German Empire). With around 7.75 million inhabitants, it was the largest and most populous colony in the German Empire .

Founded as a private colony of the German-East African Society

Political background

In the 1880s there were voices in Germany calling for an intensified colonial policy . Chancellor Otto von Bismarck rejected this at the beginning because he wanted to focus on Europe in terms of foreign policy. But feared social and economic tensions prompted German colonial supporters to act. The economy allegedly lacked new sales markets that would already bring great wealth to the other European colonial powers. Ruling economic circles hoped for a weakening of the growing labor movement through an emigration campaign with the aim of settling a "German India" overseas, where there are supposedly brilliant opportunities for development. This idea fell on fertile soil in nationalist-minded circles of the bourgeoisie and the nobility.

The German-East African Society

The driving force behind the establishment of the colony was the pastor's son Carl Peters , who was commissioned by the Society for German Colonization, which he himself founded , to take possession of areas in Africa. On November 10, 1884, Peters arrived in Zanzibar with companions . He traveled in camouflage because his plan should remain undetected by the British and the Sultan of Zanzibar .

A little later, the first " protection treaties " were concluded on the mainland, with which the colonization society justified its claims to areas in today's Tanzania, the real meaning of which, however, was mostly not understood by the chiefs who signed. Chancellor Bismarck was initially against the establishment of the colony, had informed the British envoy Malet in November 1884 that Germany had no intentions on Zanzibar and instructed the German representation in Zanzibar not to give Peters any support. When Peters returned to Berlin with his treaties during the Congo Conference and threatened an agreement with the Belgian King Leopold, the Chancellor relented for domestic political reasons and on February 27, 1885 issued a letter of protection signed by Kaiser Wilhelm I. This letter of protection legitimized the occupation of East African territories under the name German East Africa after the name Petersland, which was considered by Peters' friends, was rejected by the same.

The meanwhile renamed German-East African Society (DOAG) under the direction of Carl Peters now had the backing of the German Reich and expanded the range of its claims gained through "protection contracts". This expansion met the protest of the government of Zanzibar, which ruled the coast of the East African mainland between Mozambique and Somalia and also claimed the hinterland as far as the Congo area, in which it had little influence off the caravan routes. On April 27, 1885, she addressed a protest note to the emperor and reinforced her troops on the mainland. Chancellor Bismarck then sent a naval squadron under Admiral Knorr to Zanzibar , despite major concerns, forcing the Sultan to recognize the DOAG acquisitions. At the same time, the DOAG also tried to acquire the entire Somali coast between Buur Gaabo and Aluula .

In the following year, Germany and Great Britain agreed in the British-German Agreement on the delimitation of their spheres of influence in East Africa of November 1, 1886 ; it was agreed to recognize the sovereignty of Zanzibar and the sultan's property was limited to a 10-mile-wide strip of mainland between Kionga and the Tana Estuary, some cities in Somalia and the islands of Zanzibar, Pemba, Mafia and Lamu. At the same time, the British promised to exert their influence on the Sultan so that he would agree to the lease of the port administration of Dar es Salaam and Pangani to the DOAG - without access to the sea, the value of the acquisitions on the mainland was very limited.

Based on this German-British agreement, which put the Sultan under pressure, Peters succeeded in 1887 in concluding a contract with the Sultan on the administration of the entire Zanzibari coastal strip between the two rivers Umba and Rovuma . Thereafter, the DOAG should take over the administration of the Zanzibari mainland area and the collection of the coastal tariffs in the name of the Sultan for an annual rent.

Riot on the coast

When the treaty came into force in 1888, a major part of the coastal population under Buschiri bin Salim from Tanga in the north to Lindi in the south against attempts at German occupation (the so-called Arab uprising ) took place immediately . The loose rule of the DOAG collapsed and the Bagamoyo and Dar es Salaam stations could only be held through the use of German marines .

The Reich government then sent the young officer Hermann Wissmann, who was experienced in Africa, to East Africa as Reich Commissioner. With the help of a mercenary force of German officers as well as Sudanese and Zulu , it was possible to put down the revolt. The leader of the uprising, Buschiri bin Salim, was executed on December 15, 1889. The intervention of the empire was presented to the public as a measure against the Arab slave trade, which was carried out in accordance with the international legal provisions of the Congo Act.

While the DOAG rule on the coast was effectively over, Peters was back in the hinterland to conclude contracts in the area of Lake Victoria. In February 1890, he also reached an agreement with the ruler of Buganda .

Takeover of the colony by the empire

In fact, with the arrival of Reich Commissioner Wissmann, control had already passed to the German state. During the year 1890, the provisions were negotiated under which the Reich should also formally take over the ownership claims of the DOAG.

Demarcation

On July 1, 1890, the Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty between Germany and Great Britain was concluded. The treaty regulated the transfer of the North Sea island of Heligoland and the Caprivi Strip (now part of Namibia ) to the German Empire, while Wituland (now part of Kenya ) and the claims to Uganda were ceded to Great Britain. In doing so, the government put a final stop to Peter’s efforts, who in the meantime had tried to expand the DOAG area again by signing contracts with the Kabaka of Buganda . The area west of Lake Tanganyika, for which Paul Reichard had requested Reich protection, had already been recognized as part of the Congo state.

After a border conflict with Portugal , only the small Kionga triangle in the extreme southeast of the protected area was added in 1894 .

Consolidation of colonial rule

In 1891, German East Africa was officially placed under the administration of the German Reich as a "protected area", and the soldiers of Wissmann were officially designated as Schutztruppe . The first civil governor was Julius Freiherr von Soden from 1891 to 1893 . He was followed in 1893-1895 by Colonel Friedrich von Schele , who, after disputes with the Maasai, carried out a military expedition against the Hehe in 1894 and captured the fortress of Kuironga from Chief Mkwawa . Carl Peters had been appointed Reich Commissioner for the Kilimanjaro area in 1891, but was recalled to Germany in 1892.

Under Governor Eduard von Liebert (1897–1901), the Schutztruppe carried out further campaigns and brought most of the country under their control, including the Hehe in 1898 . The overthrown Sultan Chalid ibn Barghasch of Zanzibar, who exercised a calming influence on the East African aristocracy in Dar es Salaam , was also helpful .

Administrative division

The administrative organization developed from the coast to the interior. Districts were set up as administrative organizations on the coast and military stations in the interior. In 1888 Bagamojo , Daressalam , Kilwa , Lindi , Mikindani , Pangani and Tanga were the seats of the district chiefs of the German-East African Society.

In 1890 the German Empire divided the colony into a northern and a southern province. In 1891 they returned to the division into districts. Five districts were set up on the coast, headed by a district captain. With the stabilization of the military situation inland, the military stations there were gradually converted into districts. In 1893 there were the seven districts of Bagamojo, Daressalam, Kilwa, Lindi, Pangani, Tabora and Langenburg . The district captain now bore the title of district administrator. In the following years, the Kilossa military station was converted into a district and the Rufiji district was newly established.

In 1905 the colony was divided into 22 districts; 10 of them were subordinate to district offices of the civil administration, and a further 12 as "military districts" to the commanders of the protection force. In addition, there were 14 district branches (as of 1912).

- District offices in German East Africa (selection)

District Offices

Military districts

In 1906 the residences of Rwanda , Urundi and Bukoba were formed from the military districts of Usumbura and Bukoba . These were the representations of the protected area with the local sultanates in the area of Uhaya (Bukoba), Rwanda and Urundi. Here German rule was based on the British system of "indirect rule".

In 1914 there were 19 civil district offices. Iringa and Mahenge were military districts.

currency

From 1890 to 1916 the German East African rupee was the currency in German East Africa. It continued to circulate in Tanganyika until 1920.

Administration of justice

The administration of justice vis-à-vis the German population and the Europeans treated as “fellow protectors” was carried out by district courts and the higher court in Dar es Salaam. District courts existed in Dar es Salaam, Tanga, Muansa, Moshi, and Tabora in 1914. These courts were also responsible to the few Europeans in the sultanates of Rwanda and Burundi.

In relation to the local population, district officials were principally entrusted with the administration of criminal justice as heads of the administrative districts. The district courts and the higher court expressly did not have jurisdiction. Often tribal chiefs were left with jurisdiction over their tribesmen; so these fines could go up to 100 rupees. If the district officer took over the jurisdiction, village elders were appointed to local judges, so-called "Walis", who advised the German officials on criminal customs and customs.

Flags

The flag of the governor of German East Africa was used in 1891. In 1914 a coat of arms and a flag for German East Africa were planned, but no longer introduced due to the start of the war.

Economy and Transport

At the beginning of the 20th century, the introduction of cotton , rubber and sisal crops promoted agricultural development. The Amani Biological-Agricultural Institute was established in the Usambara Mountains in 1902 and was then the most modern facility of its kind in Africa. The agriculturally necessary labor was partly used as forced labor . In general, however, the introduction of taxes forced the African population to take up wage labor. The taxes were to be paid in cash, which the locals could only get through wage labor from Europeans. As there was fear of a collapse of the local economy, house slavery , which was common in pre-colonial times, was still allowed. It is estimated that around 1900 around ten percent of the population of East Africa were slaves.

Commercial products

Export products were: ivory, raw rubber, sesame, copra, resins, coconuts, mats, wood, horns, coffee and hippopotamus teeth.

Export earnings were:

- 1902: 5,283,290 ℳ

- 1903: 6,738,906 ℳ (including exports by land: 7,054,207)

The following were imported: Cotton products, rice, iron goods, wine, butter, cheese, bacon, ham, meat, beer, petroleum, vegetables & fruits, flour, tobacco, brandy worth:

- 1902: 8,858,463 ℳ

- 1903: 10,688,804 (including imports by land: 11,188,052 ℳ)

Railways

The Usambara and Tanganyika lines were important railway lines in German East Africa . In addition, there were short connecting routes and small railways operated by the plantation companies. A railway line for the development of the northwest, the Rwanda Railway , as well as in the south of the colony was no longer realized due to the First World War . An important builder and operator was the East African Railway Company , which was founded on June 29, 1904 with its seat in Berlin. In 1914, about 1628 kilometers of line were in operation in German East Africa .

Shipping

Shipping traffic between Europe and German East Africa and coastal shipping was mainly handled by the German East Africa Line, founded in 1890 . In addition, ships of the British India Steam Navigation Company and other companies called German East Africa. Only the coastal cities of Dar es Salaam and Tanga, which handled the overseas traffic , had notable port and landing facilities . There was also a brisk traffic with local sailing ships ( dhows ). To protect against reefs and sandbanks , buoys were laid and lighthouses were built on the coastal spots . A floating dock was operated in Dar es Salaam from 1902 , which saved German and foreign ships long maintenance trips. In 1906, the disinfection and fire - fighting boat Clayton vehicle A was stationed in the port of Dar es Salaam to fight epidemics and fires .

Smaller barges and government steamers operated on Lake Malawi , Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria .

Colonial societies

The following colonial societies became economically active in German East Africa:

- the Central African Lakes Society, founded in 1902 by Otto Schloifer

- the Central African Mining Society, founded in 1905 by Otto Schloifer

- the Kironda-Goldminen-Gesellschaft, founded in 1908 by Otto Schloifer

- the German-East African Society in Berlin, founded in 1885

- the German-East African Plantation Society in Berlin, founded in 1886

- the L. & O. Hansing, Mrima agriculture and plantation company in Hamburg

- the Usambara coffee building company in Berlin, founded in 1893

- the Pangani Society in Berlin, constituted in 1894

- the Rheinische Handeï-Plantagen-Gesellschaft in Cologne, founded in 1895

- the West German trading and plantation company Düsseldorf, founded in 1895 a. a. by Albert Poensgen

- Sigi-Pflanzungsgesellschaft mbH in Essen an der Ruhr, founded in 1897

- Montangesellschaft mbH in Berlin, founded in 1895

- the Irangi Society in Berlin, founded in 1896

- Usindja-Gold-Syndikat , later Victoria-Njansa-Gold-Syndikat, Berlin, founded in 1896

- Kilimandjaro trading and agricultural company , formerly Kilimandjaro ostrich breeding company in Berlin, founded in 1895

- Coffee plantation Sakarre AG in Berlin, founded in 1898

- Lindi-Hinterland-Gesellschaft mbH in Koblenz, formerly Karl Perrot & Co., German Lindi, trading and plantation company in Wiesbaden, founded in 1900

- German Agave Society in Berlin, founded in 1902 a. a. by Albert Poensgen

- Bergbaufeld Luisenfelde GmbH in Berlin, founded in 1902

- East African Plantation Society Kilwa-Südland GmbH in Berlin, founded in 1908

- Ulanga Reis- und Handelsgesellschaft mbH in Hamburg, founded in 1914

Communications

In German East Africa, a network of post and telegraph companies was created. More remote post offices away from the railways were connected by messenger mail. The private forerunner East African Sea Mail was followed by state mail connections to the hinterland from 1894. Telegraph lines ran from Tanga to Mikindani , from Tanga to Aruscha , from Kilossa to Iringa and from Dar es Salaam via Kilossa and Tabora to Muansa . Local telephone networks were installed in around a dozen places. The submarine cable of the Eastern and South African Telegraph Company , which ran into Bagamojo and Dar es Salaam , connected the colony to the world telegraph network via Zanzibar. By 1914, three radio stations for wireless telegraphy were built, which were used for intra-African and coastal radio traffic. In the interior of the country, Muansa and Bukoba on Lake Victoria were equipped with radio stations in 1911. Dar es Salaam received a coast radio station in 1913. A transcontinental large-scale radio station based on the model of the radio station Kamina (the station in the Togo colony ) was supposed to be built near Tabora, but was no longer possible due to the outbreak of the First World War .

The Maji Maji uprising

Due to increasing repressive measures, the increase in taxes and especially the introduction of the so-called village shambs (cotton fields on which the inhabitants of a village were forced to work), the Maji Maji uprising broke out in 1905 . The first unrest occurred in the second half of July in the Matumbi Mountains, west of the coastal town of Kilwa . The German colonial administration in Dar es Salaam still hoped at this point that it was a locally limited event. However, this assessment by the governor Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen turned out to be completely wrong no later than August 15, when insurgents stormed the military post in Liwale . The resistance against colonial rule finally assumed threatening proportions for the Germans.

The particular danger for the colonial administration lay in the structure of the resistance, which quickly spread across ethnic and political borders. Within a few weeks and months, different ethnic groups joined the uprising movement. This was mainly made possible by the Maji cult , which took up traditional myths and met with resonance in various areas. The prophet Kinjikitile Ngwale preached the resistance against the Germans and spread his message with the help of “holy water” (water = maji) as a kind of medicine. The Maji was supposed to protect the insurgents in battle by turning the enemy bullets into drops of water. The integrative power of the Maji cult reached its climax in the battle of Mahenge : In the storming of the Mahenge boma on August 30, 1905, several thousand Africans attacked the German post, which was supported by around 80 soldiers and 200 loyal locals was defended. In machine gun fire , however, the Maji failed, and the attackers suffered devastating losses.

The Mahenge setback, however, did not mean the end of the expansion of the uprising. Other groups joined the movement and by October the insurgents controlled about half of the colony. In the wake of the heavy open field battles, the insurgents soon shifted to waging a small war against the Germans, which continued until 1907, albeit without the previous overarching cooperation.

From 1906, the Germans used a "scorched earth strategy" against the guerrilla tactics of the insurgents. Villages were destroyed, crops and inventories burned, well filled and members of the ringleaders in " guilt by association taken" to the rebels to withdraw the basis for warfare. But the consequence was also a devastating famine , which depopulated entire stretches of land and which permanently changed the social structures of African society. The losses on the part of the insurgents are now estimated at 100,000 to 300,000 people. On the other side, 15 Europeans and 389 African soldiers were killed. The number of German soldiers in the colony (excluding African Askari ) was never more than 1000 men during the entire uprising (in addition to the protection force, crew members of German warships were deployed as "land soldiers" as well as civilians who volunteered to war, including a number of non-German whites, mostly British and South Africans ). The Reichstag in Berlin did not want to approve any additional funds for the suppression of the uprising, since the colony had to “support itself” in contrast to German South West Africa, which was intended as a “ settlement colony ” .

For various reasons, the events in East Africa were hardly noticed in the German Reich and were or are still in the shadow of the war and genocide in German South West Africa . In order to ensure the stability of the colony, the system of rule was defused after the end of the war under the new governor Rechenberg . However, the reform measures largely failed due to the resistance of the white settlers. Nevertheless, there was no resistance worth mentioning until the end of German rule in East Africa.

The population on the eve of the world war

The colonial contradictions persisted even after the end of the Maji Maji War. In the most populous colony of the German Empire, there were only over 5,000 Europeans for every 7.5 million locals, who mainly stayed at the coastal squares and official offices. In the years before the First World War, minor settlement from Europe began, especially around Kilimanjaro and in the Usambara Mountains . The mild mountain climate was considered more bearable by Europeans compared to the southern savannas and swamps. In 1913, however, there were only 882 German settlers (farmers and planters) in the colony. In contrast, around 70,000 Africans worked on the plantations of German East Africa. Among the remaining Germans at that time there were many government officials (551) and members of the protection and police forces (260 and 65, respectively). Within the Europeans, different mentalities emerged between the plantation owners and the urban population. In the eyes of many farmers, the townspeople stood for excessive bureaucratization and a land policy that was perceived as too good-natured. In addition to Africans and Europeans, there were Asian parts of the population (namely Arabs and Indians). They played an important role in the colony's trade and local government, but their position was often uncertain as they were not fully recognized by either the African majority society or the European power elite.

| Population in German East Africa (1913) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| nationwide | thereof in Dar es Salaam | ||

| African | approx. 7,645,000 | 19,000 | |

| Arabs | 4000 | ||

| In the | 8800 | 2629 | |

| Europeans | 5339 (including 4107 Germans) |

967 | |

| total | 7,663,139 | 22,596 | |

The German colonial rulers also disagreed on religion and school policy, particularly on the role of Islam. Although the share of the Islamic inhabitants of German East Africa in the total population was only about four percent, opinions about them show different views. The majority of the German colonial administration took the standpoint of religious neutrality and valued the Muslim residents as largely loyal subjects. The church-related parties, such as the center , as well as church representatives, on the other hand, saw Christian proselytizing in danger through equal treatment. Within school policy, this formed the framework for the dispute between supporters of government schools and those of mission schools. Muslims were also trained at government schools, giving them opportunities for advancement. This was denied to them in the mission schools. Even if the proportion of government schools was far lower than that of mission schools (approx. 8% compared to 92% in 1911), Muslims were promoted by the government and gladly placed in the lower administration.

The First World War

The colony was fought over throughout the First World War . By March 1916, the Schutztruppe succeeded in repelling an attempt by British-Indian troops to land near Tanga , made several advances into neighboring British and Belgian areas and held off most of the area against initial attacks from Kenya. In 1916 the Allies had then gathered stronger forces and marched into German East Africa from Kenya, the Belgian Congo and Nyassaland. Within a few months they had pushed the protection force back to the impassable south of the country. After heavy fighting, the Schutztruppe withdrew under their commander Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck in November 1917 to Mozambique , Portugal , where they fought retreats with Allied troops for several months. In October 1918, the protection force penetrated through the south of German East Africa into Northern Rhodesia . Due to the late arrival of news of the armistice in Compiègne , the war in East Africa did not end until November 25, 1918 with an agreement to transfer the protection force to Germany.

The fighting resulted in severe devastation in the country from 1916 onwards. There were hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, mainly due to the many deaths among the porters who were forced to carry out transport services for the military , a worsening famine from 1917 and the effects of the global flu epidemic from 1918 to 1920 on the weakened population.

The Versailles Treaty

The Versailles Treaty determined that Germany had to surrender all colonies . German East Africa was placed under the administration of the League of Nations on January 20, 1920 . The area of German East Africa was divided up between Belgium and Great Britain according to previous agreements. Belgium received mandates over Burundi and Rwanda and Great Britain the mandate over Tanganyika . In the south, the small Kionga triangle fell on Portuguese East Africa ( Mozambique ), which pushed the border to the mouth of the Rovuma .

List of governors of German East Africa

In East Africa, a representative of the German government appeared for the first time in 1888 with Wissmann as Reich's military commissioner. Previously there were various stations and representations of the German-East African Society that could not exercise any governmental power; Carl Peters was appointed "first executive officer" with general power of attorney by the colonial society in 1885. The first attempt to take on sovereign tasks collapsed after a few days with the uprising of 1888 .

- 1888–1891: Hermann von Wissmann (Reich Commissioner)

- 1891–1893: Julius Freiherr von Soden

- 1893–1895: Friedrich Radbod Freiherr von Schele

- 1895–1896: Hermann von Wissmann

- 1896–1901: Eduard von Liebert

- 1901–1906: Gustav Adolf Graf von Götzen

- 1906–1912: Georg Albrecht Freiherr von Rechenberg

- 1912–1918: Heinrich Albert Schnee

German place names

- Bismarckburg ( Kasanga )

- New Gottorp ( Uvinza )

- Neu-Langenburg ( Tukuyu )

- Sphinx Harbor ( Liuli )

- Wilhelmstal ( Lushoto )

The highest mountain in Africa, the Kibo in the Kilimanjaro massif, was known as the Kaiser Wilhelm peak .

Movies

- The horsemen of German East Africa

- Mamba , USA 1930, directed by Albert S. Rogell

- Headhunt in East Africa (= episode 2 of the docu-drama series Das Weltreich der Deutschen ), 45 min., Germany 2010.

- Love for Empire - Germany's dark past in Africa, documentary , 60 min., Director: Peter Heller , D 1978.

See also

literature

- Norbert Aas, Werena Rosenke (Hrsg.): Colonial history in the family album . Early photos from the German East Africa colony. Münster: Unrast, 1992. ISBN 3-928300-13-X .

- Martin Baer, Olaf Schröter: A head hunt. Germans in East Africa Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3-86153-248-4 .

- Detlef Bald: German East Africa 1900–1914: a study on administration, interest groups and economic development. Munich: Weltforum-Verlag, 1970. ISBN 3-8039-0038-7 .

- Felicitas Becker, Jigal Beez: The Maji Maji War in German East Africa 1905–1907. Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag, 2005. ISBN 3-86153-358-8 .

- Tanja Bührer: The Imperial Protection Force for German East Africa. Colonial security policy and transcultural warfare, 1885 to 1918. Contributions to military history, vol. 70. Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag 2011. ISBN 978-3-486-70442-6 .

- Imre Josef Demhardt: The cartography of the imperial protected area German East Africa. In: Cartographica Helvetica Heft 30 (2004) pp. 11–21 full text

- Small German Colonial Atlas , 3rd edition ed. by the German Colonial Society published by Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), Berlin 1899, with comments on the maps (description of the colonial areas). 2002 edition by the Weltbild GmbH publishing group in Augsburg, ISBN 3-8289-0526-9 .

- Fritz Ferdinand Müller: Germany - Zanzibar - East Africa: History of a German colonial conquest 1884–1890; with 14 illustrations and 6 maps. Berlin: Rütten & Loening, 1959

- Michael Pesek : The end of a colonial empire. East Africa during the First World War . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010. ISBN 978-3-593-39184-7 .

- Rainer Tetzlaff: Colonial development and exploitation: Economic and social history of German East Africa 1885–1914 Berlin: Duncker [below] Humblot, 1970

- Dirk Bittner: Great Illustrated History of East Africa . Melchior Verlag, 2012, ISBN 3-942562-86-3 .

- Ulrich van der Heyden: Colonial everyday life in German East Africa in documents. (Trafo-Verlag, Berlin 2009)

Web links

- The German East Africa colony German Historical Museum

- 1914-18. The war in German East Africa German Historical Museum

- Klaus Richter : German East Africa 1885 to 1890: On the way from the protection letter system to the imperial colonial administration , in forum historiae iuris (Internet journal for legal history)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael Pesek: The end of a colonial empire. Campus, Frankfurt a. M./New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-593-39184-7 , pp. 86/90.

- ↑ Zum.de - Colonial Atlas

- ↑ Communication on November 28, 1884, see Hertslett (1894), The Map of Africa by Treaty Vol II, footnote p. 605, online at archive.org

- ↑ Carl Peters: Memorabilia (1918) online here on google books

- ↑ Johann Frömbgen: Wissmann, Peters, Kruger . Stuttgart: Franckh'sche Verlagshandlung, 1941, p. 122.

- ↑ Bartholomäus Grill : Wir Herrenmenschen - Our racist legacy: A journey into German colonial history. 2nd edition, Siedler, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-8275-0110-3 , p. 35.

- ↑ cf. Point 1 of the Agreement of November 1, 1886, see Hertslett (1894), The Map of Africa by Treaty Vol II, p. 615 f., Online at archive.org

- ^ Reichard, Paul , in: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon. Volume III, p. 146.

- ↑ Without a name : The German-Portuguese border dispute, in: Karl Homann (Ed.): Latest Mittheilungen. Berlin, July 31, 1894.

- ↑ Command office order of August 6, 1890, DKB 1890, p. 211

- ↑ DKB 1891, p. 334

- ↑ a b Walther Hubatsch (Ed.): Outline of German administrative history: 1815 - 1945. Vol. 22. Federal and Reich authorities, 1983, ISBN 3-87969-156-8 , p. 369

- ↑ From footnote: Map-Small Colonial Atlas 1905

- ↑ Michael Pesek: The end of a colonial empire: East Africa in the First World War, Frankfurt am Main 2010: Campus Verlag, ISBN 978-3-593-39184-7 , p. 35 ( online excerpt from academia.edu )

- ↑ Footnote on the German East Africa map in the Colonial Lexicon 1913 ; Usumbura fell away from the military districts mentioned in 1905, and the residencies took its place

- ↑ Julian Steinkröger: Criminal law and the administration of criminal justice in the German colonies: A comparison of law within the possessions of the empire overseas. Dr. Kovač, Hamburg 2019, pp. 317–319

- ^ Sebastian Conrad : German colonial history . Beck, Munich 2012, pp. 55-60.

- ↑ from: Colonial Atlas

- ^ East African Railway Company , in the German Colonial Lexicon

- ^ Franz Baltzer : The colonial railways with special consideration of Africa . Berlin 1916, Reprint: Leipzig 2008, p. 99, ISBN 978-3-8262-0233-9 . ( Preview on Google Books )

- ^ German East Africa : Transport, in the German Colonial Lexicon

- ^ Rudolf Fitzner: German Colonial Handbook. Volume 1, 2nd ext. Ed., Hermann Paetel, Berlin 1901, p. 262 f. (Reprint, Melchior Verlag, Wolfenbüttel 2006, ISBN 978-3-939102-38-0 ).

- ^ Deutsche Post (ed.): Carrier pigeons, balloons, tin cans. Mail delivery between innovation and curiosity . Without publisher information , without location information 2013, chapter East African Lake Mail , p. 120 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Klein-Arendt: “Kamina ruft Nauen!” The radio stations in the German colonies 1904–1918 . 3rd edition, Cologne: Wilhelm Herbst Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-923925-58-1 .

- ↑ Bernd G. Längin : The German colonies . Hamburg / Berlin / Bonn: Mittler, 2005, ISBN 3-8132-0854-0 , p. 217.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: German colonial history . Munich: CH Beck, 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-56248-8 , p. 64.

- ^ Wilfried Westphal: History of the German Colonies. Gondrom, Bindlach 1991, ISBN 3-8112-0905-1 , p. 350f.

- ^ Uwe Timm: German colonies . Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1986, ISBN 3-89340-019-2 , p. 197.

- ^ Winfried Speitkamp: German Colonial History . Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005, ISBN 978-3-15-017047-2 , p. 110.

- ↑ Armin Owzar : Loyal vassals or Islamic rebels? Muslims in German East Africa, in: Ulrich van der Heyden and Joachim Zeller (eds.): Colonialism in this country - A search for traces in Germany. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2007, ISBN 978-3-86680-269-8 , pp. 234-239.

- ^ J. Wagner, German East Africa, History of the Society for German Colonization and the German East African Society, according to the official sources, Berlin 1886, online at archive.org