German Central Africa

The establishment of a colony "German Central Africa" was a subordinate German colonial project and war goal in both the First and Second World Wars .

Pre-war plans

Even before the First World War, there were several attempts to expand the German colonial empire into areas of Central Africa . In the early phase Paul Reichard tried to acquire parts of what would later become the Katanga province for Germany. However, they were awarded to the Congo Free State by the German government , so they rejected the protection of the Reich requested in February 1886. Eduard Schulze's initiative at Nokki in the lower Congo was also rejected. Between 1894 and 1911, the German advance was expressed geographically in the so-called duck's bill in the northeast of the German colony of Cameroon . This area protruded into the area of today's state of Chad . However, it was ceded to France in 1911 in exchange for New Cameroon . France's offer to swap German Togo for an even larger area in Equatorial Africa was dropped after protests by German colonial politicians and traders.

Uganda treaty

In 1890 Carl Peters tried to conclude a protection treaty with the king of Buganda , Mwanga II , in what is now Uganda . The treaty was intended to lay the foundation for the expansion of German East Africa into a German India in Africa . The ratification of the treaty, so the colonial German hope, would have given Germany influence between the Congo Basin , Sudan and East Africa . Due to Mwanga's caution (who only signed a friendship agreement ), competition from Great Britain and the Heligoland-Zanzibar treaty , the Uganda treaty gained no significance.

Morocco-Congo Treaty

The Morocco-Congo Agreement of November 4, 1911, concluded as a result of the Second Morocco Crisis , included the enlargement of the German colony of Cameroon as compensation for French activities in Morocco . The aim of German policy was to gain direct access to the navigable Congo and, in view of the expected division of the Belgian Congo to other colonial powers, to create a favorable starting position for rounding off German colonial holdings in Central Africa. In its southern and eastern foothills, the enlarged Cameroon now extended over parts of the Congo Basin. German territory extended through the Ssanga summit directly to the Congo. The eastern tip touched the Ubangi tributary .

Angola Treaty

In the German-British negotiations on the division of the Portuguese and Belgian Africa holdings, there were initial concrete plans. In July 1913, the government representative von Kühlmann reached an agreement with the British negotiating partners: In the event of Portugal's financial difficulties, Germany should be entitled to Angola , apart from the border area with northern Rhodesia , as well as Sao Tomé and Principe , while England claimed Mozambique up to Lugenda . A proposal by State Secretary of the Reich Colonial Office, Wilhelm Solf, to circumcise the Belgian Congo, with Katanga and the extreme northeast to Great Britain, the region north of the Congo to France and a broad connection between Angola and German East Africa to the Reich, ultimately failed due to British resistance . To enforce claims against indebted Portugal seemed much easier than against economically prosperous Belgium.

First World War

The central goal of German colonial policy was a colonial empire in Central Africa that was as closed as possible through land bridges between the colonies of East Africa , South West Africa and Cameroon .

1914 plans

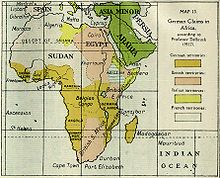

Another suggestion by Solf, who drafted a specific Central Africa project in August and September 1914, was the distribution of the African colonies of France, Belgium and Portugal , which Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg finally included in his September program. The new closed Central African colonial empire of Germany should encompass the following areas: Angola, the northern half of Mozambique, Belgian Congo, with the Katangas copper mines as the most valuable individual object, French Equatorial Africa up to the level of Lake Chad , Dahomé and the area south of the Niger arc up to Timbuktu . This project of creating a coherent Central African colonial empire remained, in some areas still greatly expanded, from then on fundamentally part of the official German war aims.

Plans from 1916/17

In the unlikely event that the Entente would accept the peace offer of the Central Powers , Bethmann Hollweg asked the General Staff, Admiralty Staff and Colonial Office to draw up war target lists as a basis for negotiation, which happened immediately. Admiral's chief of staff Holtzendorff's maritime war aims of December 24, 1916, appraised and approved by the Supreme Army Command , had a fantastic character : In addition to bases in the North and Baltic Seas, the first breach in England's sea-dominating geographic location was to be made together with the Azores . To connect and protect the colonial empire, you should get to Dakar or, if necessary, Cape Verde . East African ports, Zanzibar and Madagascar are still needed as bases to threaten the English route to India . The State Secretary of the Colonial Office, Solf, demanded in the war target program of his department, in addition to the return of all German colonies, the consolidation of African colonial possessions through the acquisition of French, Belgian, Portuguese and possibly also English colonies into a "German-Central African Empire". In addition, he called for the expansion of this Central African empire to the west, into the economically developed areas of the recruiting of the colored French .

1918 plans

In the spring of 1918, Solf even agreed to the demands of the German Colonial Association . According to these, in addition to the old claims in Central Africa, the river basins of Senegal and Niger and south of these to the sea (i.e. with Nigeria ) should fall to the German Empire - the German colonial rule would therefore have spread from Cape Verde to the Orange River in the west Northern Rhodesia , Northern Mozambique, Uganda , Kenya , Madagascar, the Comoros and Djibouti to the east. In May 1917, the Admiral's staff called for bases for the preservation of the future world empire, in addition to worldwide naval bases in Africa, to Dakar with Senegal and Gambia as hinterland (elsewhere also the Cape Verde and Canary Islands and Madeira ) and Réunion .

Significance for German politics

Overall, however, the “Central Africa Project” and the base program only played a subordinate role in German war policy, as it was believed that a victory in Europe would achieve them by itself. On the other hand, in the further course of the war, the goal of "Central Africa" was used more and more by liberal-minded politicians as a substitute and diversion goal for the nation, away from wild annexation demands in Europe. For Germany, colonies were more of a fancy dress and an expression of its (world) power. The concepts for a closed German Central Africa expected visible proof of the German world power from their realization and calculated that the area would acquire the importance for Germany that India had for Great Britain. But even before the war, heavy industry and banks had shown little interest in colonial empires that lay in the moon and pushed for European expansion.

Second World War

On the eve of the Second World War and during the war, the German side again made plans for a colonial reorganization of Africa. Again, a central African colonial empire was the focus and main goal of these plans. The original efforts to find a settlement with Great Britain exclusively at the expense of French and Belgian colonial possessions were adjusted in 1942 in favor of a colonial settlement between the Greater German Reich, France and Spain. In contrast to the First World War, Germany no longer made any claims to the colonies of Portugal, which was also ruled by fascism.

Reorganization with no British assignments

The return of the four formerly German colonies in Africa or the handing over of the mandate over them to Germany was taken for granted by the National Socialist regime and propagated. German “minimum requirements” that went beyond the four former German colonies initially only extended to Belgian Congo and French Equatorial Africa with French Congo, Gabon, Ubangi-Shari (Central Africa) and southern Chad to Lake Chad and Dahome (Benin ) as well as the port cities Dakar, Conakry (Guinea), Mogador (Morocco) and Agadir (Morocco) with their respective hinterland.

Djibouti, Tunis and northern Chad were to fall to Italy. In 1940, in Hendaye, Spain demanded French Morocco, parts of Algeria (Department Oran: Oran and its hinterland, 67,262 km²) to shift the southern border of Spanish Sahara to the 20th parallel and to expand the coastal area of Spanish Guinea in return for entering the war Pages of Germany and Italy.

Berlin hoped to acquire Kenya, Uganda, Northern Rhodesia and Nigeria and possibly the Gold Coast (Ghana) from Great Britain, which corresponded to the demands made during the First World War. German naval bases were to be established in Zanzibar, the Seychelles, the Comoros, Mauritius, Reunion, Sao Tome, Fernando Poo, Sankt Helena, Cape Verde, the Canaries, Sao Miguel and the Azores.

However, the attempt to come to an agreement with Great Britain at the expense of France, already mentioned in Hitler's Mein Kampf , initially provided for the rest of British colonial possessions to be spared or a guarantee of the British acquis. If, therefore, no assignments are obtained from Great Britain, France would also have to assign large parts of French West Africa to Germany: the majority of Niger, Upper Volta, the Ivory Coast and parts of Mali south of the Niger Arc, possibly also all of Senegal, Guinea and Madagascar. The same also applied in the event that an agreement with Great Britain did not come about, but the German-Italian conquest of British colonial possessions would also fail.

Reorganization at the expense of Great Britain

In deviation from the original plans for conquest, the National Socialist regime adjusted its demands after the failure of a compromise with Great Britain. The USA and Great Britain had agreed not to conclude a separate peace with the Greater German Reich ("Washington Pact" of January 1, 1942 as part of the Arcadia Conference ). As early as 1941, Germany had also laid claim to the Gold Coast (Ghana), Sierra Leone, Gambia, Nyassaland and Southern Rhodesia. In January 1942, Ernst Woermann , Undersecretary of State in the Foreign Office, instead outlined concessions to Vichy France : Vichy France was promised compensation for German colonial demands in West Africa at the expense of British colonial possessions. Britain was to lose all of its African colonial possessions to Germany and its fascist allies Spain and Italy, and to France and the South African Union .

For the Central African colonial empire of Germany, France was supposed to cede “only” French Equatorial Africa (up to Lake Chad) in addition to the return of Cameroon. For a future “Jewish state” under German protectorate, Germany also demanded Madagascar. For Madagascar (and Syria), France should be compensated with the western half of Nigeria, the Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. Germany was even ready to hand over the former German colony of Togo to France.

From Great Britain and Belgium, in addition to Tanganyika, the eastern half of Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Northern Rhodesia and Congo were to belong to German Central Africa. Southern Rhodesia should be left to South Africa. Italy laid claim to the British colonies of Sudan and Somaliland.

However, the areas available as compensation were not sufficient to take into account the Italian claims and the German attempt to include Franco-Spain in addition to Vichy France. Instead of French Morocco, Spain should therefore be resigned to Sierra Leone (also offered to France) and possibly western Nigeria and Liberia as well as a border adjustment in the south of Spanish Western Sahara. In return, Spain was even supposed to cede Spanish Guinea to German Central Africa. Nazi Germany, on the other hand, was prepared to forego southern Chad and Ubangi-Shari (French Central Africa) in relation to France if Spain were to be taken into account. Corresponding negotiations between Hitler, Franco and Petain failed, however.

Egypt and South Africa

For Egypt, which was to be left formally independent, the fascist allies wanted Italy to take over all the special rights previously reserved for Great Britain, while the German Empire sought (at French expense) to acquire a majority of the Suez Canal shares.

The South African Union was to be completely detached from British influence and won over as an ally of Germany. In addition, Germany recognized possible claims of South Africa on Southern Rhodesia and possibly Bechuanaland (Botswana), Basutoland (Lesotho) and Swaziland. A negotiated solution was to be found about the former colony of German South West Africa (Namibia), which was already under South African administration . On the South African side, these goals were essentially supported by Oswald Pirow , a right-wing extremist politician and multiple minister.

Abandonment of the colonial plans

With the final Italian defeat in Ethiopia ( Battle of Gondar in November 1941), the defeat of the German-Italian Africa Corps in front of El-Alamein (November 1942), the subsequent occupation of the French colonies in North Africa by British and US Americans ( Operation Torch im November 1942) and the German defeat at Stalingrad (January 1943) there was no longer any prospect of direct military conquests in Africa and the Middle East. At the beginning of 1943, an order issued by Martin Bormann on Hitler's behalf ended all activity in colonial territory. All previously Vichy-French colonies were already under the free French control of de Gaulle at this point, so they were no longer available. In May 1943 the German-Italian Africa Corps capitulated.

In contrast, for example, to the German naval command, Hitler assigned a subordinate role to far-off African possessions anyway. For him (as for the extreme right in World War I), areas in Eastern Europe that could be directly connected to the German “living space” were in the foreground.

literature

- Dirk van Laak : Imperial Infrastructure. German plans for the development of Africa from 1880 to 1960. Schöningh, Paderborn / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-506-71745-6 (Zugl .: Jena, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 2001).

- Karsten Linne: Germany beyond the equator? The Nazi colonial planning for Africa. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-500-3 .

- Sönke Neitzel : "Middle Africa". On the importance of a catchphrase in German world politics of high imperialism. In: Wolfgang Elz (ed.): International relations in the 19th and 20th centuries. Festschrift for Winfried Baumgart on the 65th birthday of Schöningh, Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-70140-1 , pp. 83-104.

- Rolf Peter Tschapek: Building blocks of a future German Central Africa. German Imperialism and the Portuguese Colonies. German interest in the South African colonies of Portugal from the end of the 19th century to the First World War. Steiner, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-515-07592-5 ( review ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Conrad Weidmann: German men in Africa - Lexicon of the most outstanding German Africa researchers, missionaries, etc. Bernhard Nöhring, Lübeck 1894, p. 146.

- ^ Reichard, Paul , in: Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon. Volume III, p. 146.

- ^ Horst founder: History of the German colonies . 5th edition, Paderborn: Schöningh / UTB, 2004, p. 101, ISBN 3-506-99415-8 ( book preview on Googlebooks )

- ^ Wilfried Westphal: History of the German colonies . Bindlach: Gondrom, 1991, p. 126ff., ISBN 3-8112-0905-1 .

- ↑ Fritz Fischer: War of Illusions. German politics from 1911 to 1914 . Düsseldorf 1969, pp. 448-458; and Wolfgang J. Mommsen: The Age of Imperialism (= Fischer World History Volume 28) . Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-60028-6 , p. 265.

- ↑ Wolfdieter Bihl (Hrsg.): German sources for the history of the First World War . Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-08570-1 , pp. 58f. (Doc. No. 16); and Fritz Fischer : reaching for world power. The war policy of imperial Germany 1914/18. Droste, Düsseldorf 1964, p. 115f.

- ^ Klaus Epstein: The Development of German-Austrian War Aims in the Spring of 1917 . In: Journal of Central European Affairs 17 (1957), pp. 24–47, here: p. 27.

- ^ André Scherer, Jacques Grunewald: L'Allemagne et les problemèmes de la paix pendant la première guerre mondiale. Documents extraits des archives de l'Office allemand des Affaires étrangères. 4 volumes (German original documents). Paris 1962/1978, ISBN 2-85944-010-0 , Volume 1, pp. 136ff. (No. 117); and Gerhard Ritter: statecraft and war craft. The problem of "militarism" in Germany. Volume 3: The tragedy of statecraft. Bethmann Hollweg as war chancellor (1914-1917) . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 1964, p. 352.

- ^ Fritz Fischer: Reach for world power. The war policy of imperial Germany 1914/18. Düsseldorf 1964, pp. 415f; and Wolfgang Steglich: securing alliances or peace of understanding. Investigations into the peace offer of the Central Powers of December 12, 1916 . Musterschmidt publishing house, Göttingen / Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1958, p. 158.

- ↑ Wolfdieter Bihl (Hrsg.): German sources for the history of the First World War . Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-08570-1 , pp. 283f. (Doc.No.142); and André Scherer, Jacques Grunewald: L'Allemagne et les problemèmes de la paix pendant la première guerre mondiale. Documents extraits des archives de l'Office allemand des Affaires étrangères. 4 volumes (German original documents). Paris 1962/1978, ISBN 2-85944-010-0 , Volume 2, pp. 214f. (No. 129).

- ↑ Andreas Hillgruber: The failed great power. A sketch of the German Empire 1871-1945 . Düsseldorf 1980, ISBN 3-7700-0564-3 , p. 51.

- ^ Karl Dietrich Erdmann : The First World War . Munich 1980 (= Gebhardt: Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte Vol. 18), ISBN 3-423-04218-4 , p. 54.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Loth : History of Africa. Volume 2: Africa under imperialist colonial rule and the formation of anti-colonial forces 1884–1945. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1976, p. 237f.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, map 6.

- ^ A b Diplomats Ribbentrops in the Foreign Service of Bonn . ( Memento of December 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) In: Braunbuch, Berlin 1965. pp. 233-278.

- ↑ Karsten Linne: Germany beyond the equator? The Nazi colonial planning for Africa. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-500-3 , pp. 81ff.

- ↑ a b c Heinz Hoffmann (Ed.): History of the Second World War 1939–1945 with extensive maps. (12 volumes) ( German and Italian colonial plans in Africa and the Middle East 1939–1941. ) Berlin 1973–1982, map 27.

- ↑ Karsten Linne: Germany beyond the equator? The Nazi colonial planning for Africa. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-500-3 , pp. 140f.

- ↑ a b Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, p. 238.

- ↑ Karsten Linne: Germany beyond the equator? The Nazi colonial planning for Africa. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-500-3 , pp. 83ff.

- ^ Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, p. 230 and 238.

- ↑ Karsten Linne: Germany beyond the equator? The Nazi colonial planning for Africa. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86153-500-3 , p. 81.

- ^ Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, p. 239f.

- ^ Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, p. 240.

- ^ Heinrich Loth: History of Africa. Part II, Berlin 1976, pp. 232 and 236.

- ↑ Federal Agency for Civic Education: Germany in Africa. Colonialism and its aftermath.