German New Guinea

|

German New Guinea Micronesia and Melanesia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Capital : | Berlin , German Empire | ||||

| Administrative headquarters: | 1885–1891: Finschhafen 1891–1892: Stephansort 1892–1899: Friedrich-Wilhelms-Hafen 1899–1910: Herbertshöhe 1910–1914: Simpsonhafen 1914: Toma (provisional) |

||||

| Administrative organization: | |||||

| Head of the colony: | 1884–1888: Kaiser Wilhelm I. 1888: Kaiser Friedrich III. 1888–1914: Kaiser Wilhelm II. |

||||

| Colony Governor: | see List of Governors of German New Guinea | ||||

| Residents: | approx. 480,000 inhabitants (1912) | ||||

| Currency: | 1885–1911: New Guinea Mark , from 1911: Gold Mark |

||||

| Takeover: | 1884 - 1914 protected area | ||||

| Today's areas: |

Papua New Guinea Micronesia Northern Mariana Islands Palau Nauru Marshall Islands Solomon Islands (northern part) |

||||

In 1899, under the name of German New Guinea , the German Empire took over the imperial protected area in Oceania administered by the German New Guinea Company . With the exception of German Samoa , German New Guinea comprised the entirety of all German colonies or protected areas located in the South Pacific (the so-called " German South Sea ").

German New Guinea included:

- Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land on the island of New Guinea

- the islands in the Bismarck Archipelago :

- the northern Solomon Islands

- the Carolines (administered as East and West Carolines)

- the Northern Mariana Islands (excluding Guam )

- Palau

- Nauru

- and the Marshall Islands (1885–1906 separate protected area)

History at the time of the German Empire

Pre- and early phase (1883–1885)

Queensland is annexing ahead

Because of a growing need for plantation workers, both the Australian colony of Queensland and the European landowners in Samoa began to force recruiting of islanders in the New Britain and Solomon Islands archipelago in the early 1880s . As a result of a trade-policy conflict of interests between Australian and German merchants, the colony of Queensland (Australia) reacted in April 1883 with an advance annexation of all land masses of New Guinea not claimed by the Netherlands (i.e. the main island east of the 141st degree of longitude).

On March 15, Queensland Prime Minister Thomas McIlwraith dispatched the Thursday Island Police Magistrate Henry Chester to Port Moresby without prior consultation with the London Colonial Office . This is where Chester hoisted the Union Jack on April 4, 1883, and declared eastern New Guinea a British colony. An application was subsequently sent to London for approval, but was rejected by Colonial Minister Lord Derby . In support of this, the Queensland government was asked to come to an agreement there (and possibly in other Australian colonies) on assuming the administrative costs for the new protectorate, after which the question of raising the flag in Port Moresby would be dealt with again in London.

German-English territorial demarcation

A casual remark by Lord Derby that he personally saw no need for a British colonial establishment in New Guinea because there was “no foreign power” among the other large nation states that wanted to take possession of the area, led to around sixty protests in Australia. In November 1883 these protests culminated in an intercolonial convention in Sydney, at the end of which a resolution was passed calling for London to "take immediate steps" for the annexation of New Guinea, including all islands to the south and north.

Following a confidential communication to the German ambassador in London that, in recognition of German economic interests in northern New Guinea, the government of Great Britain would limit its protectorate only to the south coast and the islands in front of it, Lord Derby responded negatively to the Sydney resolution. In September 1884, however, the British government turned around and informed Berlin in a note that Great Britain would now accept the demands of the Sydney Convention and also raise territorial claims on the north coast of New Guinea, "from the Eastern Cape to the 145th degree east longitude". Because preparations had already begun for the first German flag hoisting in the island area, this and the ensuing entanglements led to a conference in London in February 1885. At it, the spheres of interest of both nations in Oceania were diplomatically delimited. The claims of Great Britain on the southern and eastern parts of New Guinea (→ British New Guinea ), as well as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands were established . In contrast, the territory of the later Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land on the northeast coast of New Guinea fell to the German Empire , including the islands off the coast to the north. H. of the so-called Bismarck Archipelago from 1885 . Samoa , Tonga , the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides remained independent for the time being. Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land and the Bismarck Archipelago formed the "old protected area" of German New Guinea, which was expanded to include "new" protected areas with the next flag-raising and territorial acquisitions.

The South Seas colonial program of the Disconto Society

On behalf of parts of the German financial elite, the banker Adolph von Hansemann had formulated a program in his secret memorandum, German interests in the South Seas (September 1880), which was supposed to make the establishment of a German South Seas protected area possible regardless of a democratic approval by the Reichstag or Bundesrat . Among other things, this was a reaction to the attitude of Bismarck, who after the fall of the Samoa bill (April 1880) did not see enough support in the German population to launch such a colonial program in parliament. According to von Hansemann, it was therefore necessary first of all for “a few to unite in any social form” and then to make the necessary resources available at “[their own] risk for a national cause”. Only in the event of success would a “large” company be founded (the later New Guinea Company ), whose task it was to carry out the actual colonial program.

The purpose of the initially to be formed "small" society was, starting from the ports of Mioko and Makada ( Duke of York Islands ), which after an "acquisition" by Corvette Captain Bartholomäus von Werner in December 1878 were already regarded as ports of the Imperial Admiralty were to establish a steamship connection to other South Sea islands and, in association with the Imperial Navy, to occupy the northeast coast of New Guinea with trading and coal stations. As far as the support of the Reich was concerned, the operators of the preliminary program could rely on Bismarck's promise that the Reich would give them “maritime and consular protection” even if the aforementioned actions were carried out by private entrepreneurs.

As a "small" society, a consortium came together in the spring of 1884 to prepare and establish a South Sea Island Compagnie ( New Guinea Consortium for short ), whose committee included Adolph von Hansemann and Gerson von Bleichröder , the German consul general in Sydney, Carl Sahl , and the Oppenheim jr. (Cologne) counted. The company Robertson & Hernsheim in Hamburg was initially to be entrusted with the practical part of the taking of possession , because Hansemann had admitted that their subsidiary in the South Sea, Hernsheim & Co , had the necessary means to carry it out. However, the company manager Franz Hernsheim refused to cooperate because the speculative colonial project of the Hansemanns to sell the captured land masses back to free settlers and entrepreneurs, if possible without state building, seemed morally and commercially unjustifiable. Instead, from June 1884, von Hansemann turned to the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesellschaft ( DHPG ) and at the same time commissioned the Bremen ornithologist Otto Finsch to put together an expedition team. Finsch had already toured the island area of New Guinea on ships from Hernsheim & Co in 1880/81 .

The Australian-British screw steamer Sophia Ann was bought by the New Guinea Consortium in July 1884 , which was renamed Samoa after being refitted in Sydney . To keep the expedition secret, Samoa was declared to the Phoenix Islands (September 11th), whereby the trip - with Otto Finsch as leader and the Arkis driver Eduard Dallmann as captain - supposedly served purely scientific purposes. The accompanying warships SMS Hyäne and Elisabeth sailed from Sydney (October 2 and 16) with sealed orders and the DHPG was only entrusted with insignificant auxiliary services, also for reasons of secrecy.

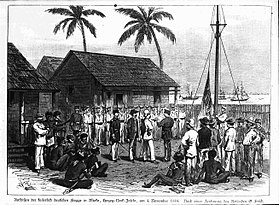

Flag hoisting for "German New Guinea"

During the Samoa stop before Mioko (September 26th) the Imperial Commissioner for the New Britain Archipelago, Gustav von Oertzen , was embarked. In addition to Otto Finsch's first "land purchases" in Konstantinhafen and Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen (both Astrolabe Bay, New Guinea), von Oertzen concluded "Reich Treaties" with the coastal residents, which, according to Finsch, the Papuans understood "even less" than their own agreements. After a first return to the New Britain archipelago and a meeting with SMS Hyäne and SMS Elisabeth (arrival October 21st and November 1st), they hoisted on November 3rd, 1884 on the premises of the headquarters of Hernsheim & Co on Matupi (Blanche Bay, New Britain) the Imperial flag. Further hoists took place on November 4th on Mioko ( Duke of York Islands , main branch of DHPG ) and during the following days on stations of both companies on the north and east beaches of the Gazelle Peninsula . During a second voyage on the Samoa to the main coast of New Guinea, now accompanied by SMS Hyäne and Elisabeth , the first flag hoisting took place here too. On 23/24 November Finschhafen was discovered, the settlement for the first "capital" in the area of what will later become German New Guinea.

In the absence of prior notice in London, the British government viewed the flag raising as an affront to a cabinet declaration from October. It had stated that Great Britain would limit its territorial claims to the south coast of New Guinea and the offshore islands, but without prejudice to territorial questions beyond these borders . After the Colonial Minister Granville gave in, the German claims to what would later become Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the Bismarck Archipelago were enforced at the London Conference in February / March 1885.

First main phase (1886–1899)

Issuing a charter

A charter modeled on the North Borneo Company was sought as an administrative model for the new protected area . The issuance of the letter of protection to the New Guinea Company (founded: May 1884) was delayed, however, because the Reich Foreign Ministry had previously wanted to have an agreement with Robertson & Hernsheim as an important economic interest in the protected area. Because of the ideological differences between Adolph von Hansemann and Franz Hernsheim (see above), the Hamburg company management resisted taking over sovereignty by the New Guinea company , which was a core part of the charter. As a result, Robertson & Hernsheim could only be affiliated to the New Guinea company under protest .

With the assumption of sovereign rights by the New Guinea Company (letter of protection dated May 17, 1885), the company was able to manage the area autonomously, take possession of unpopulated terrain and independently complete land purchases. The right to regulate relations with foreign powers was reserved for the imperial government . In return, the company took on the obligation to “make the protected area usable”, i. H. to find usable harbors, to explore the interior of the country, to set up supply depots as well as to establish orderly legal relationships and attract settlers. The company had to provide these services self-financed or privately, i. H. without subsidies from the Reich Treasury.

Until May 1888, so-called company officials were employed to exercise the administration. They headed the trading and plantation branches of the New Guinea company , acted as customs and tax officials and performed judicial functions. The highest official in the protected area was the governor .

Management of the New Guinea company

In the spring of 1888, a volcanic eruption sank a large part of the offshore Ritter Island . A subsequent tsunami killed over 3,000 people. Among the victims were the German researchers von Below and Carl Hunstein , who were looking for suitable locations for coffee plantations . The next catastrophe followed in 1891 when New Guinea's capital Finschhafen had to be abandoned due to a malaria epidemic . In 1901, however, Finschhafen was re-established.

In 1899 common German postage stamps were printed with German New Guinea , with which the colony received its first own postage stamps.

Second main phase (1900-1914)

Takeover and development by the German Reich

Due to the threat of insolvency of the New Guinea company, the German Reich was forced to buy back the sovereign rights of the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land colony on October 7, 1898. From 1899 the German Empire administered the colonies as part of German New Guinea. The imperial governor took the place of the former governor . This was based in Herbertshöhe ( Kokopo ) on the Gazelle Peninsula in the Bismarck Archipelago. As a result, Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen (Madang) lost its position as the administrative capital .

The government promised itself that the direct administration would, among other things, stabilize the economy. However, the colony's main exports continued to consist of natural products such as rubber , copra and stone nuts . Coconut palms in particular were grown on plantations. To this end, the German colonialists brought more Chinese and Malay workers to New Guinea. Only phosphates played a noteworthy role in mining , which were mined on the islands of Nauru and Angaur, which was later acquired. Grains and pulses , metal goods, construction and timber as well as animal products were imported.

Expansion and development of the colonial area

After the German Empire was initially defeated in the Caroline dispute of 1885 , it acquired the Caroline and Palau Islands and the northern Mariana Islands from Spain in the German-Spanish Treaty of 1899 . The purchase price was 25 million pesetas (almost 17 million marks ). With this, German New Guinea expanded to the north and west. With the Samoa Treaty of 1899 , territorial disputes over the Solomon Islands were settled.

In 1905, at the instigation of the German Colonial Society, a population census and classification was carried out, the results of which were published in the German Colonial Atlases in 1906. In view of some missing information and uncertainties, the population of German New Guinea at the time can be cautiously estimated at around 200,000 locals and 1,100 Europeans, including around 700 Germans, ignoring the mixed population.

From 1910 until the First World War , the colonial government of German New Guinea found its permanent place in Rabaul . On August 6, 1914, due to the war, the seat of the governor was relocated to a rest home in Toma for a few weeks , about 12-15 kilometers inland from Herbertshöhe (Kokopo).

In 1911, the uprising of the Sokehs in the Carolines was forcibly suppressed by German marines and Melanesian auxiliaries.

The total area of German New Guinea was approx. 240,000 km 2 . The only complete census in 1912 counted 478,843 indigenous people and 772 German inhabitants.

Due to its island location, the shipping lines formed the main transport links to and from German New Guinea. The main lines were the Austral-Japan line and the New Guinea-Singapore line (both North German Lloyd ) as well as a Reichspostdampfer line of the Jaluit company . The crossing by ship from Europe to German New Guinea took an average of six weeks. Traveling time on the Trans-Siberian Railway was reduced by 35 days under favorable conditions. The journeys within the widely scattered island area were also tedious and could take up to 60 days. The international shipping connections in the colony were supported by coastal and government steamers - such as the Starfish , which went missing in 1909 . In German New Guinea there was no railway network, only short field railways existed (e.g. at Stephansort and on the phosphate islands of Angaur and Nauru ). Inland traffic on the islands took place on foot, by horse or cart. For this purpose, roads were laid out, some of which were already accessible for cars. In terms of communications, only the Yap Islands were connected to the world telegraph network by cable. Large radio stations of the German colonial radio network for wireless telegraphy were set up on Yap, Nauru and near Rabaul . A smaller radio station insisted on Angaur.

First World War (1914-1918)

At the beginning of the First World War , Australian troops occupied the Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land, Bismarck Archipelago, Solomon Islands and Nauru from August 1914, while the Marianas , Carolines , Palau and Marshall Islands were surrendered to the Japanese units almost without a fight . The high point was the occupation of the Bita Paka radio station near Rabaul by Australian units in September 1914. The invasion ended with the capture of Rabaul by over 3,000 Australian soldiers. In the province of Morobe , the German captain Hermann Detzner hid in the bush with a few men and only surrendered in November 1918.

The expulsion of the German settlers took place in stages:

- About 110 civil servants and officials were sent back home between September 22 and May 11, 1915 after spending time in Darlinghurst Prison and Liverpool Concentration Camp . The return journey of the first took place via America with the ships Sonoma (January 16, 1915) and Ventura (February 13, 1915).

- Approx. 95 German civilians were brought to the German Concentration Camps in Liverpool City , Trial Bay or Berrima ( NSW ) on the Australian mainland in 1914/15 and interned until 1919/20.

- The remaining 180 or so German settlers were expelled between 1920 and 1922. A few stayed, mostly as prospectors.

All Germans were formally expropriated after the war through the expropriation ordinances from 1921, including those who had already died or were deported. Germans who were not married to Samoan women and who were allowed to stay became impoverished. They were only allowed to receive visitors from 1926 onwards, and correspondence with their homeland was prohibited. A few colonists returned from 1928. Australia never granted any compensation.

Recent history (1920 to present)

Australia received a mandate administration over German New Guinea ( Territory of New Guinea ), in 1949 the area was united with the former British New Guinea , also under an Australian mandate ( Territory of Papua ) to form the Territory of Papua and New Guinea . In 1975 the territory of Papua and New Guinea was granted independence as part of Papua New Guinea .

After the Second World War , the Japanese League of Nations mandates came under US rule. From 1945 nuclear bomb tests were carried out on the Marshall Islands Bikini and Eniwetok . Over time, the islands were given independence:

- 1968: Nauru

- 1975: Kaiser-Wilhelms-Land, Bismarck Archipelago, Bougainville, Neupommern, Neuhannover and Neumecklenburg as part of Papua New Guinea

- 1986: The Carolines as part of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands

- 1994: Palau

The Mariana Islands have been part of the United States since 1945 , but have had a certain degree of autonomy since 1986.

Planned symbols for German New Guinea

→ Main article: Flags in the colonies of the German Empire

In 1914, a coat of arms and a flag for German New Guinea were designed, but were no longer introduced due to the outbreak of war.

Former German island and place names (selection)

- Adolfhafen or Adolphhafen: Morobe

- Eschholtz Islands: Bikini Atoll

- Friedrich Wilhelmshafen: Madang

- Count Heyden Islands: Likiep Atoll

- Herbertshöhe: Kokopo

- New Hanover: Lavongai

- New Year Islands : Mejit

- Neulauenburg: Duke of York Islands

- Neumecklenburg: New Ireland

- Neupommern: New Britain

- Simpson Harbor: Rabaul

See also

- British New Guinea 1884–1902, British colony (south-eastern part of New Guinea)

- Dutch New Guinea 1828–1963, Dutch colony (western part of New Guinea)

- Territory of New Guinea 1920–1949, Mandate of the League of Nations Australia (north-eastern part of New Guinea)

- Territory of Papua 1920–1949, Mandate of the League of Nations Australia (south-eastern part of New Guinea)

- Territory of Papua and New Guinea 1949–1971 League of Nations mandate Australia (merger of the north-east and south-east of New Guinea)

literature

- Small German Colonial Atlas , 3rd edition ed. by the German Colonial Society published by Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), Berlin 1899, with comments on the maps (description of the colonial areas), 2002 edition by the Weltbild GmbH publishing group in Augsburg, ISBN 3-8289-0526-9

- Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money: biography in two volumes . MV Science, Münster 2012.

- Peter Biskup: "Hahl at Herbertshoehe, 1896-1898: The Genesis of German Native Administration in New Guinea". In: KS Inglis (ed.): History of Melanesia . (2nd ed.). Canberra - Port Moresby 1971, pp. 77-99.

- Sebastian Conrad , Jürgen Osterhammel (Hrsg.): Das Kaiserreich transnational. Germany in the world 1871–1914. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-36733-3 .

- Stewart Firth: New Guinea under the Germans . Melbourne University Press, Melbourne (Vic) 1983, ISBN 0-522-84220-8 .

- Susanne Froehlich (ed.): As a pioneer missionary to distant New Guinea. Johann Flierl's memoirs. Part I: 1858--1886, Part II: 1886--1941. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2015 (sources and research on the South Pacific; sources 5); ISBN 978-3-447-10164-6 .

- Robert J. Foster: "Komine and Tanga: A Note on Writing the History of German New Guinea". In: Journal of Pacific History . Vol. 22, No. 1 (1987), pp. 56-64.

- Gisela Graichen , Horst founder , Holger Diedrich: German colonies. Dream and trauma. Ullstein, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-550-07637-1 .

- Bartholomäus Grill: We gentlemen. Our racist heritage. A journey into German colonial history. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 2019.

- Horst founder : history of the German colonies. (5th edition). UTB, Paderborn 2004, ISBN 3-8385-1332-0 .

- Horst founder: ... found a young Germany here and there: racism, colonies and colonial ideas from the 16th to the 20th century . dtv, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-423-30713-7 .

- W. von Hanneken: "A colony in reality: illusion-free observations by a former station master in the protected area of the New Guinea Company". In: The Nation . No. 9, pp. 133-136, and No. 10, pp. 154-157.

- Hermann Joseph Hiery : The German Empire in the South Seas (1900-1921): An approach to the experiences of different cultures . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen - Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-525-36322-2 .

- Hermann Joseph Hiery (ed.): The German South Sea 1884-1914. A manual . (2nd revised and improved edition). Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-73912-3 .

- Mary T. Huber: The Bishops' Progress: a historical ethnography of Catholic missionary experience on the Sepik frontier . Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 0-87474-544-6 .

- Verena Keck: "Representing New Guineans in German Colonial Literature". In: Paideuma: Communications on cultural studies . Vol. 54 (2008), pp. 59-83.

- Dieter Klein: New Guinea as a German utopia. August Engelhardt and his Order of the Sun. In: Hermann Joseph Hiery (ed.): Die Deutsche Südsee 1884–1914. A manual . Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-73912-3 , pp. 450–458.

- Dieter Klein (ed.): "Jehova se nami nami". Johanna Diehl's diaries. Missionary in German New Guinea 1907-1913 . Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005 (sources and research on the South Pacific; sources 1); ISBN 3-447-05078-0 .

- Dieter Klein (ed.): Pioneer missionary in Kaiser-Wilhelmsland. Wilhelm Diehl reports from German New Guinea 1906-1913 . Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 2014 (sources and research on the South Pacific; sources 4); ISBN 978-3-447-10284-1 .

- Max von Koschitzky: German Colonial History . Baldamus, Leipzig 1888.

- Carl Leidecker: In the land of the bird of paradise. Serious and cheerful from German New Guinea . Leipzig 1916.

- Cathrin Meyer zu Hoberge: Penal colonies - “a matter of the people's welfare”? The discussion about the introduction of deportation in the German Empire. ( Story 26). LIT-Verlag, Münster u. a. 1999, ISBN 3-8258-4512-5 .

- Richard Neuhauss : German New Guinea. 3 volumes. Reimer, Berlin 1911.

- John Moses and Paul Kennedy: Germany in the Pacific and Far East 1870-1914 . Queensland University Press, St Lucia (Qld) 1977, ISBN 978-0-7022-1330-4 .

- Rufus Pesch: "The Protestant Missions in German New Guinea 1886–1921". In: Hermann Joseph Hiery (ed.), Die Deutsche Südsee 1884–1914: Ein Handbuch . (2nd revised and improved edition). Schöningh: Paderborn 2002, pp. 384-416, ISBN 3-506-73912-3 .

- Peter Sack (ed.): German New Guinea: A Bibliography . Australian National University Press, Canberra (ACT) 1980, ISBN 978-0-909596-47-7 .

- Peter Sack: "German New Guinea: a reluctant plantation colony?" In: Journal de la Société des océanistes , No. 82–83, Vol. 42 (1986), pp. 109–127.

- Bernhard Schulze: The Disconto-Ring and the German expansion 1871-1890: a contribution to the relationship monopoly: state . (Inaugural dissertation). Karl Marx University, Leipzig 1965.

- Paul B. Steffen, The Catholic Missions in German New Guinea . In: Hermann Joseph Hiery (ed.): The German South Seas. A manual . (2nd revised and improved edition). Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, pp. 343-383, ISBN 3-506-73912-3 .

- Paul [B.] Steffen: Beginning of the mission in New Guinea. The beginnings of the Rhenish, Neuendettelsauer and Steyler missionary work in New Guinea . (Studia Instituti Missiologici SVD 61.) Steyler Verlag, Nettetal 1995, ISBN 3-8050-0351-X .

- Anja Voeste : "Raise the negroes"? The language question in German New Guinea (1884–1914) . In: Elisabeth Berner, Manuela Böhm, Anja Voeste ( eds .): A big and narhracht. Festschrift for Joachim Gessinger. Universitätsverlag Potsdam, Potsdam 2005, ISBN 3-937786-35-X . Full text .

- Liane Werner: History of the German colonial area in Melanesia . (Thesis, filmed and published by the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra, PMB 514). [Humboldt University, Berlin 1965].

- Arthur Wichmann: Nova Guinea: Vol. II. History of the discovery of New Guinea 1828–1885 . Bookstore and printer EJ Brill, Leiden 1910.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Karl Sapper: Marshall Islands , in: Heinrich Schnee (Hrsg.): German Colonial Lexicon. Volume 2, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 513 ff.

- ↑ Considerations and ideas about the settlement / colonization of Papua New Guinea existed decades before. An example of this is the report: New Guinea German calls from the antipodes (letter from a German businessman ...), in: August Petermann : Mittheilungen from Justus Perthes' geographical institute about important new research in the entire field of geography , 1869, p . 401–406, ( digitized version )

- ↑ Sydney Morning Herald , January 3, 1885, p. 7 (retrospective).

- ↑ quoted from Max von Koschitzky: Deutsche Colonialgeschichte . Baldamus, Leipzig 1888, p. 174.

- ^ White books South Sea: German interests in the South Sea , Vols. I and II. Contained in files R1001-2722 of the Reich Colonial Office, Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde.

- ↑ a b quoted from Liane Werner: History of the German Colonial Area in Melanesia . (Thesis, filmed and published by the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra, PMB 514). [Humboldt University, Berlin 1965], Part I, pp. 95a and b.

- ↑ Cover letter from Hansemanns to the memorandum on German interests in the South Seas , November 11, 1880. Contained in file R1001-2722 of the Reich Colonial Office, Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde.

- ↑ Liane Werner: History of the German colonial area in Melanesia . (Thesis, filmed and published by the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, Canberra, PMB 514). [Humboldt University, Berlin 1965], Part II, pp. 1 and 4.

- ↑ Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money: biography in two volumes . MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, vol. 2, p. 196 u. 210 (passim).

- ↑ An insight into the preparatory phase is provided by: Peter-Michael Pawlik: From Siberia to New Guinea: Captain Dallmann, his ships and journeys 1830–1896. An image of life in self-testimonies and contemporary testimonies . HM Hauschild, Bremen [1996].

- ↑ Copy of Finsch's communication, contained in: Comité der Neuguinea-Kompagnie to Bismarck, March 21, 1885, file R1001-2800 of the colonial department of the Foreign Office, Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde.

- ↑ quoted from Max von Koschitzky: Deutsche Colonialgeschichte . Baldamus, Leipzig 1888, p. 175, not in italics in the original.

- ↑ Cf. the Society's memorandum drawn up in this style, d. i. Robertson & Hernsheim an Kusserow, August 8, 1885, contained in file R1001-2298 of the Colonial Department of the Federal Foreign Office, Federal Archives Berlin-Lichterfelde.

- ↑ H. Klee (ed.): Volcanic eruption in the protected areas of New Guinea. In: Latest news . 7th year, No. 49, Berlin 1888.

- ^ Heinrich Schnee (ed.): German Colonial Atlas. Historical Atlas, Volume I. Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 626.

- ^ Uwe Timm: German colonies . Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-89340-019-2 , p. 203.

- ↑ Krauß: German New Guinea (Section: 15. Trade), in: Heinrich Schnee (ed.): Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon , Volume 1, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 315 ff.

- ↑ Karl Sapper : Karolinen. In: German Colonial Lexicon. Vol. II. Leipzig 1920, p. 237 ff.

- ^ Heinrich Schnee (ed.): German Colonial Atlas. Historical Atlas, Volume I. Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 315 ff.

- ↑ Karstedt: The war in the South Seas. in: Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas mit Jahrbuch 1918 , edited by the German Colonial Society, edited by P. Sprigade and M. Moisel . Overviews and reviews by Dr. Karstedt. Berlin 1918, p. 28f.

- ↑ Without author: Toma, in: Heinrich Schnee (Ed.): Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon. Volume III, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 527.

- ↑ Horst founder: History of the German colonies. 5th edition. UTB, Paderborn 2004, p. 170.

- ↑ Krauß: German New Guinea (Section: 16. Transport), in: Heinrich Schnee (ed.): Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon , Volume 1, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920, p. 315 ff.

- ↑ Battle of Bita Paka (Eng.)

- ^ Karl Baumann: Biographical Handbook German New Guinea 3rd Edition. Fassberg, 2009, pp. 4-5, pp. 613-620. (List of interned Germans from German New Guinea)

Web links

- German Historical Museum: statistical information

- Thomas Morlang: Cruel robbers that we were. In: The time . No. 39, September 23, 2010

- Traces of colonialism in Hanover: Rudolf von Bennigsen

- Emil Nolde in the South Seas. Research expedition of the Reich Colonial Office from October 1913 to September 1914

- The Imperial Navy and the Empress Augusta River Expedition 1912/13. Federal Archives