coffee

Coffee ( standard pronunciation in Germany : [ ˈkafeː ]; in Austria and Switzerland : [ kaˈfeː ] ; colloquially in northern Germany also [ ˈkafə ] ; from Turkish kahve from Arabic قهوة qahwa for "stimulating drink", originally also "wine", based on the region of origin Kaffa ) or coffee drink is a black, psychotropic , caffeinated drink made from roasted and ground coffee beans , the seeds of the fruit of the coffee plant , and hot water becomes.

The degree of roasting and grinding vary depending on the type of preparation. Coffee contains the vitamin niacin . The term "coffee beans" does not mean that the coffee is still unground, but refers to the purity of the product (Arabic bunn بن"Coffee beans", Amharic bunaa ቡና "coffee") and is used to distinguish between coffee substitutes (made from chicory , barley malt , etc.). Coffee is a luxury item .

The coffee beans are obtained from stone fruits of various types of plants from the Rubiaceae family . The two most important types of coffee plants are Coffea arabica ( Arabica coffee ) and Coffea canephora ( Robusta coffee ) with many varieties and varieties . There are different levels of quality depending on the variety and cultivation location. Coffee is grown in over 50 countries around the world. There are 124 wild coffee species, around 60% of which are endangered.

history

Legends of origin, discovery and etymology

The coffee plant comes from Africa. According to a pious legend , the Islamic prophet Mohammed first discovered the stimulating effects of coffee after the angel Gabriel offered him a cup of hot, dark liquid.

After a 1671 of Antonius Faustus Naironus (1636-1707) in his book De saluberrima potione cahve committed to paper legend, once shepherds from the southwest of the present-day Ethiopia lying Kingdom of Kaffa have noticed that some of the goat herd, which with from a shrub had eaten white flowers and red fruits, jumped cheerfully into the night while the other animals were tired. The shepherds (according to another version, a Yemeni shepherd) complained about this to monks of the nearby monastery. When an Abyssinian shepherd (whose name is often given as Kaldi ) tried the fruits of the shrub himself, he noticed an invigorating effect on himself. While researching the grazing site, the monks discovered some dark green plants with cherry-like fruits. They made an infusion out of it and from then on could stay up late into the night, pray and talk to each other and are said to have traded with the plant. Other sources say that the shepherd spat the inedible fruit into the fire in disgust, whereupon scents were released; this is how the idea of roasting came about.

It is believed that the Kaffa region in southwest Ethiopia is the region of origin of coffee. There he was mentioned as early as the 9th century. Coffee probably came to Arabia from Ethiopia in the 14th century through slave traders. It was probably not roasted and drunk there until the middle of the 15th century. The cultivation of coffee brought Arabia a monopoly role . The trading center was the port city of Mocha, also known as Mokka, today's al-Mukha in Yemen. The Ethiopian method of preparation and coffee tradition is probably the most original: After roasting the beans in a large iron pan, they are roughly ground or pounded in a mortar. The grist is boiled with water and sugar in the so-called jabana , a bulbous clay jug similar to a carafe, and served in small bowls. The word coffee can be traced back to the Arabic qahwa , which can refer to “coffee” as well as “wine”. Via the Turkish kahve it got into Italian ( caffè ) and from there into French, the word form café was adopted into German without major phonetic changes and only the spelling was adapted. The Turkish ambassador Soliman Aga is said to have served coffee to the distinguished society of Versailles for the first time in 1669.

In the German-speaking world, the word form coffee from English or Dutch initially dominated , it was not until the 18th century that coffee caught on after the French café .

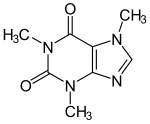

By Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , the idea came that one should the beans distill . When converting the idea of chemists discovered Fried Ferdinand Runge the caffeine .

Ottoman Empire

In the 16th century, coffee conquered the Persian Safavid Empire and the Ottoman Empire . The first coffee houses were built in Mecca around 1511 , which were subsequently closed again for some time due to a ban on coffee that was subject to severe penalties. The drink was first guaranteed for Cairo in 1532, and it also spread to Syria and Asia Minor . Coffee consumption took a special boom after the Ottoman annexation of Yemen and the opposite coast in 1538. Finally, in 1554 - after fierce opposition from the Islamic clergy and state authorities - the first coffee house was opened in the capital, Istanbul . Murad III issued a coffee ban at the end of the 16th century, which was initially only little controlled. It was not until Murad IV. Coffee houses were torn down and coffee drinkers exposed to severe persecution. Coffee house owners therefore sometimes disguised their bars as barber shops . The drink was finally recognized in the course of the reform policy of the Tanzimat from 1839.

Europe

The Augsburg doctor Leonhard Rauwolf already got to know in 1573 in Aleppo the enjoyment of the coffee drink called "chaube" according to Rauwolf by the inhabitants of Aleppo and reported about it in 1582. More news about coffee reached Italy through Prospero Alpino in 1592. In 1645 Venice, 1650 Oxford and 1652 London had coffee houses. In France, such institutions were established in Marseille around 1659. In 1672 an Armenian opened a coffee shop in St. Germain . The first Parisian café is Café Procope , which was opened around 1689 by the Sicilian Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli .

The spread of coffee as a luxury food in Europe went in the 17th century mainly from the court of Louis XIV and Louis XV. in France. The luxury goods were drunk hot and with sugar there.

The significant spread of coffee was made by the establishment of the first decorated in the 16th century by the Arabs, then by the Ottomans and finally in the 17th century in Europe coffeehouses . The first Viennese coffee house opened in 1685. It was an Armenian named Johannes Theodat who, in 1685, was granted the privilege of being the only trader in the city to sell coffee as a drink from the city leaders. The fact that the Pole Georg Franz Kolschitzky opened the first coffee house with 500 sacks of coffee, which would have been captured by the victory over the Turks before Vienna in 1683 , is a reference to the realm of legends. The piarist Gottfried Uhlich put this into the world in 1783 in his chronicle History of the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna at the centenary commemorative celebration .

The coffee had already reached the German-speaking area beforehand. In 1673 a coffee house was opened in Bremen and in the same year a license was granted to a Dutchman. In Hamburg in 1677 an Englishman opened a coffee and tea house based on the London model, after coffee is said to have been served in the Eimbeck house for the first time in 1668 . A Dutch competitor soon followed, and by 1694 there were already four coffee houses in Hamburg. Regensburg followed in 1686 and Leipzig in 1694. The coffee house in Schütting in Bremen was built in 1697 . In the same year founded prey Turk Mehmet Sadullah Pasha, 1695 baptized in the Juliusspital in the name of Johann Ernst Nicolauß Strauss, a coffee house in Wuerzburg . In 1675 coffee was already known at the court of the Great Elector in Berlin; the first coffee house was opened in Berlin in 1721.

In the 17th century, the coffee plant spread to Dutch colonies such as Java and secured the United Netherlands supremacy in trade. Coffee consumption quickly spread to ever wider circles of society. The import of coffee and its regulation were particularly important in the mercantilist economic system. In 1766 , Frederick the Great banned the private importation and trade of coffee. Only the Prussian state was allowed to trade in coffee. This should prevent the outflow of capital abroad and fill the state treasury. The ban made smuggling coffee beans lucrative. In 1781, roasting coffee for private individuals was also banned in Prussia. So-called " Kaffeeriecher ", former French soldiers, were hired to monitor the ban . They were supposed to detect illegal coffee roasting in the Prussian communes through their sense of smell. In 1787, the state coffee monopoly in Prussia was abolished again because the controls proved to be ineffective and the damage caused by smuggling increased.

Distribution of the coffee plant

While the coffee plants were initially only widespread in Africa and Arabia, the idea of cultivating them in other suitable regions soon came up. The first planting outside of Africa and Arabia was done by van Hoorn , who, as governor of the Dutch East Indies, had the first attempts made in Ceylon in 1690 (according to other sources as early as 1658) and in Java in 1696 (or 1699) . The plants used there came from Arabia. Several specimens of these plantations came to Europe in 1710 and were cultivated here in several botanical gardens, for example in Amsterdam, where a coffee bush was first grown on European soil.

In 1718 the Dutch brought coffee to Suriname , the French to Cayenne in 1725 , to Martinique in 1720/1723 , to Guadeloupe in 1730 , and the Portuguese brought the first coffee plants to Brazil in 1727, where, as everywhere in the Latin American plantation economy, African slaves had to work. As early as the end of the 18th century, coffee was one of the most widespread crops in the tropics. This is also due to the expansion of the European colonies, without which today's global distribution of coffee cannot be understood.

African slaves were exploited on the Latin American and Caribbean coffee plantations until the gradual abolition of slavery and the slave trade. The Dutch author Eduard Douwes Dekker described the living conditions of coffee growers in the Dutch East Indies in his work Max Havelaar . After all, the Europeans even exported the coffee obtained from overseas colonies to the Ottoman Empire, from where it originally began its triumphal march around the world; accordingly, the proportion of Yemeni coffee there decreased.

enjoyment

Originally, only well-off citizens and aristocrats could afford the aromatic drink. The poorer sections of the population and in times of crisis replaced coffee with drinks similar to coffee , such as muckefuck , malt coffee , Stragelkaffee or chicory . The expression “real coffee beans”, which is now less widely used, was created to distinguish it from substitute products that are also referred to as coffee.

Afternoon coffee drinking is established in some countries . Drinking coffee is also common with or after other meals. Coffee drinking had been widespread in Germany since 1733 at the latest. In the poorer sections of the population, however, the drink remained something special for a long time. It was presented to visitors in special coffee dishes, remained a Sunday drink and part of festive meals. In the 19th century, the motto “ families can make coffee here ” was associated with the Sunday excursion in the Berlin area and soon elsewhere as well. Note:

Literature and art

Soon after its introduction, coffee was seen as a means of “promoting poetry” (Johann Neukirch: The beginnings of pure German poetry. Halle 1724). In Minna von Barnhelm , Lessing addressed him as "the dear, melancholy coffee!" In the eighth book of Poetry and Truth, Goethe mused on the “very own dreary mood” in which the coffee, “especially enjoyed with milk after the table”, put it: “The coffee […] paralyzed my bowels and seemed to completely cancel out their functions so that I therefore felt great anxiety, but without being able to make up my mind to adopt a more sensible way of life. "

Honoré de Balzac always drank a lot of strong coffee to stay awake, since he usually worked twelve hours a day. Ludwig van Beethoven had the habit of counting exactly 60 coffee beans in order to brew a cup of mocha .

Curiosities

Coffee consumption was also criticized early on. This criticism is met with humor in the coffee cantata from 1734 by Johann Sebastian Bach (text based on Picander ). Nevertheless, Carl Gottlieb Hering (1766–1853) composed the well-known canon “Caffee, don't drink so much coffee!” With the six initial notes of CAFFEE.

According to a popular anecdote, the Swedish King Gustav III. tried to prove that coffee was toxic. For this purpose two prisoners sentenced to death are said to have been pardoned; one inmate had to drink tea, the other coffee, every day. However, these two are said to have survived both the supervising doctors and the king.

production

Economical meaning

At least 20 to 25 million families worldwide make a living from growing coffee. "With an assumed average family size of five people, more than 100 million people are dependent on [growing] coffee."

Around ten percent of roasted coffee is sold as decaffeinated coffee (data from 2004).

World production

A total of 10.3 million tons of green coffee were harvested worldwide in 2018. The table gives an overview of the 10 largest producers of coffee worldwide, which together reaped 84.6% of world production:

| Harvest quantities in 2018 (in t) coffee beans |

|

|---|---|

| country | harvest |

|

|

3,556,638 |

|

|

1,616,307 |

|

|

722.461 |

|

|

720,634 |

|

|

481.053 |

|

|

470.221 |

|

|

369,622 |

|

|

326,982 |

|

|

245,580 |

|

|

211,200 |

| world | 10,303,122 |

| Source: FAO | |

trade

In 2016, global coffee exports were worth $ 19.4 billion. More than two thirds of the global green coffee trade was handled through Switzerland. Germany was the fifth largest exporter with a value of 991.6 million US dollars.

Coffee is not "the second most important [legal] commercial product in the world after petroleum , [but is] the second most valuable commercial product exported by developing countries". For some countries, such as East Timor , it is the only export item worth mentioning. Coffee revenues fluctuate strongly: They fell from 14 billion US dollars in 1986 (a record amount at the time) to 4.9 billion US dollars in the crisis year 2001/2002. This so-called coffee crisis - it lasted for several years - had consequences for coffee producers all over the world.

Cultivation

Coffee plants

For the production of the coffee drink mainly the types Arabica and Robusta are used, to a lesser extent the types Liberica and Excelsa. The first yields are three to four year old bushes, from an age of around 20 the yield per bush decreases.

In 2005 there were around ten billion of the species Arabica ( Coffea arabica ) and around four billion of the species Robusta ( Coffea canephora ). Together, these two types provide 98% of the world's green coffee. Robusta coffee mostly comes from West Africa, Uganda, Indonesia and Vietnam, but also from Brazil and India. Arabica coffee is mainly grown in the countries of Latin America, East Africa, India and Papua New Guinea. According to an Oxfam study from 2002, 70% of the coffee comes from smallholders.

climate

Coffee bushes (or trees) need a balanced climate without temperature extremes, without too much sunshine and heat. The average temperatures should be between 18 and 25 ° C, the temperature should not exceed 30 ° C and should not often fall below 13 ° C, the plants cannot tolerate temperatures below 0 ° C. The water requirement is 250 to 300 millimeters per month, which is why the annual rainfall must be 1500 to 2000 millimeters, below 1000 millimeters per year is irrigated, below 800 millimeters per year coffee is not grown. Robusta coffee requires more rainfall than Arabica coffee. A lot of wind and sunshine are damaging, whereas hedges and shade trees are planted. The soil must be deep, loose and permeable (well "ventilated"), humic on top and neutral to slightly acidic.

The growing areas lie between the tropics, according to requirements, with Arabica coffee at heights of about 600 to 1200 meters above sea level. NN., With Robusta coffee between 300 and 800 meters above sea level. NN. Highland coffees (Arabica) are of a particularly high quality.

Propagation and care

Coffee is propagated by seeds , cuttings or by grafting , mostly seeds. The seeds (coffee beans) have the highest germination capacity eight weeks after the fruit ripens , after which it decreases. They are freed from the parchment membrane and sown in germ beds. The first two leaves of the seedling appear after five to six weeks. Then the young plants are transplanted into containers and further cultivated in nursery beds. When they are eight months old, they are planted in the plantation, at intervals of one to four meters, depending on the variety. As they grow further, they are trimmed in height to 1.5 to 3 meters as required. At the age of three to five years the yield is optimal and remains 10 to 20 years maximum, after which it decreases.

Environmental impact

Growing coffee has a significant impact on the environment. Traditionally, coffee was grown in the shade of large surrounding trees. With this method, part of the natural habitat is preserved, which is accompanied by a significantly higher biodiversity . In places, the diversity even approaches that of the pristine forest, even if it usually decreases as a result of management. Because the maturity time of such drawn coffee longer and per hectare find less coffee plant space, many coffee farmers (exacerbated in the wake of falling world prices by the coffee crisis Note .: ) gone over to clear existing trees and coffee beans in large monocultures to pull the open air . The existing studies show a drastic effect on biodiversity. Among other things, American migratory birds can no longer find shelter in the tree-free plantations, and attempts are made to balance the balance of pests and beneficial insects that can be observed in traditional coffee cultivation by using environmentally harmful pesticides .

According to the environmental protection organization WWF, there is a close connection between the “sun coffee” described above and tropical deforestation . Among the 50 countries with the highest rate of deforestation between 1990 and 1995 are 37 producers of coffee. The 25 most important coffee exporters lost 70,000 km² of forest area annually in the same period. The result is a significant decline in biodiversity, in the case of birds by up to 90%. Further consequences are increased soil erosion , especially in shifting cultivation and with the use of herbicides , which destroy the protective vegetation layer of the soil, as well as declining water quality in the vicinity of coffee plantations. The latter is well illustrated by the calculation that a total of 140 liters of virtual water are required for growing, roasting, shipping and preparing a cup of coffee .

The ecological cultivation of coffee has a significantly lower environmental impact . In organic farming, among other things, the use of pesticides is prohibited, while measures must be taken to prevent soil erosion. At the same time, the income of some organic coffee farmers can be stabilized, which is the case in Chiapas , Mexico, for example . In 2010, around 6.5% of the world's coffee-growing area was organically farmed, with over 90% of this area in Peru, Ethiopia and Mexico.

harvest

Once a year is harvested, in some growing areas twice. The harvest is north of the equator from July to December, south of the equator from April to August. In the vicinity of the equator, the harvest can be in all seasons. The harvest takes up to ten or even twelve weeks because the fruits take different lengths of time to ripen on the same bush. Picking by hand in such a way that only the ripe fruits are harvested results in better quality. Arabica coffee in particular is selectively handpicked using the so-called “picking method”. Inferior quality has to be accepted if all fruits are stripped by hand or with a machine, regardless of their degree of ripeness (“stripping method”) in order to save work. However, re-sorting improves the quality. Strip harvesting is used for Robusta coffee and for Arabica coffee in Brazil and Ethiopia, which is then processed dry (see processing). Harvesting machines are used on large plantations in Brazil.

The world average green coffee yield is around 680 kg / ha, in Angola 33 kg / ha, in Costa Rica 1620 kg / ha, new plantations in Brazil produce 4200 kg / ha. To get a sack with 60 kg of green coffee, it is necessary to harvest 100 well-bearing arabica trees.

processing

During processing, the skin , the pulp (also called pulp ), the mucus on the parchment skin, the parchment skin and - as far as possible - the silver skin are removed to extract the green coffee .

This can be achieved on the dry route as well as on the wet route. When deciding which type of processing to use, the aim is usually to avoid errors and loss of quality as much as possible, as these affect the price and can represent an existential risk for the coffee farmers. However, there are increasing numbers of farmers who use specific processing methods to consciously influence the taste of the coffee. Coffees prepared dry (“natural”) are generally sweeter and full-bodied than wet (“washed”) coffees. In contrast, wet processed beans are valued for their complex and clear taste profile. In mixed forms, the attempt is made to work out the clarity of the coffee and at the same time to preserve the coffee a slight sweetness and more "body".

| Type | Wet processing | Dry processing |

|---|---|---|

| Robusta | Asia (Indonesia, India, Papua New Guinea) | Africa (Uganda, Angola, Tanzania) |

| Arabica | Standard practice outside of Brazil | Brazil and up to 10% in other countries |

The very rare and expensive Indonesian Kopi Luwak undergoes an additional and special type of preparation . It occurs when the Luwak sneak cat eats coffee cherries and excretes beans whose taste properties have changed due to fermentation in the animals' intestines. Among other things, bitter substances are removed from them.

Dry processing

With dry processing, the coffee fruits ("coffee cherries"), which contain around 50 to 60% water, are spread out and turned from time to time until they have dried to a water content of around 12%. This takes about three to five weeks. Then the dry skin and pulp are mechanically peeled off.

Wet processing

Wet processing is started within 12 hours, at the latest 24 hours after the harvest. First it is pre-cleaned with water (hand or machine) and pre-sorted by washing. Then the fruit skin and pulp are squeezed off in a “pulper”, the parchment membrane and the mucus sticking to it remain on the coffee beans. The beans are transported through a flood channel and sieves into fermentation tanks. There is a fermentation ( fermentation ) instead, the mucus liquefied and thus washable. After 12 to 36 hours of fermentation, the beans are washed, then spread out to dry (sun, air, hot air if necessary) and dried to a water content of about 12%. For wet processing, 130 to 150 liters of water are required per kilogram of market-ready green coffee.

Semi-dry preparation

In order to save water when there is a water shortage and still achieve a higher quality than with dry processing, a so-called semi-dry processing is used: After washing, the pulp is largely squeezed off, but then it is not fermented, but dried immediately. Then, as in dry processing, the dry skin and pulp are peeled off the coffee beans.

Clean

After processing, the coffee beans are still surrounded by the parchment membrane (so-called "parchment coffee"). The skin of parchment and, if possible, also the skin of silver are removed by peeling.

In a final treatment, any remaining impurities are removed and the beans - with high-quality coffees by hand - sorted, that is, sorted according to size and quality. This results in the green coffee that is ready for the market.

Roast

The beans are roasted to make green coffee palatable. In general, roasting is the dry heating of the coffee beans, usually under atmospheric pressure. The roasted material goes through various chemical and physical processes through which the roasted coffee-specific color, flavor and aroma substances are formed. The roasting process begins at 60 ° C and ends in the traditional roasting process at around 200–250 ° C, or in the time-saving industrial roasting process at temperatures of up to 550 ° C. The type and quality of the green coffee beans, as well as the roasting time and temperature, determine the degree of roasting and essentially influence the formation of aromas, the development of flavors and digestibility. Fast industrial roasts at high temperatures build up more pollutants, such as melanoidins and acrylamide . Light roasts lead to a tart but less bitter taste, while darker roasts taste slightly sweet but bitter.

The heat transfer to the surface of the coffee beans takes place by means of convection , radiation and contact. However, there is an increasing transition from contact roasting to convection roasting, in which the coffee is washed with directly or indirectly heated air, thus improving the heat transfer to the roast. The following roasting processes are common:

- Batch roasting either in the drum roaster or in the fluid bed roaster

- Continuous roasting, during which the coffee is transported and roasted in rotating drums with an internal transport system

Roast level

- Light roast = pale or cinnamon roast

- Medium roast = American roast, breakfast roast

- Strong roast = light French roast, Viennese roast

- Double roast = continental roast, French roast

- Italian roast = espresso roast

- Café torrefacto (Spanish for roasted coffee) = roasting with the addition of sugar, especially common in Spain. The coffee roasted in this way is mixed with the conventionally roasted ( tueste natural ) to 20-50%, the result is called mezcla (Spanish for mixture). A mezcla 70/30, for example, consists of 70% tueste natural and 30% café torrefacto. This type of roasting softens the acidity and bitterness of the coffee blend.

trade

|

Harvest year |

Export volume (in t) |

Export value (in USD million) |

Value / t (in USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 122,623 | 193.637 | 1,579.12 |

| 2004 | 108,565 | 197.640 | 1,820.48 |

| 2005 | 112,408 | 262,260 | 2,333.11 |

| 2006 | 96,805 | 250.195 | 2,584.53 |

| 2007 | 91,665 | 254,912 | 2,780.91 |

| 2008 | 109,777 | 337,429 | 3,073.77 |

| 2009 | 78,337 | 237,088 | 3,026.51 |

| 2010 | 74,218 | 261.841 | 3,528.00 |

| 2011 | 76,400 | 375.867 | 4,919.73 |

| 2012 | 87,148 | 418,564 | 4,919.73 |

| 2013 | 81,464 | 302.806 | 3,717.05 |

| 2014 | 72,817 | 277,330 | 3,121.94 |

| 2015 | 68,579 | 305,956 | 4,461.37 |

| 2016 | 75,495 | 307.910 | 4,078.55 |

The most important customer countries are the USA , Germany , France , Japan and Italy .

Beginning at the end of 2001, the coffee price returned to a slight upward trend. Since the end of 2004, coffee prices have risen more sharply again. According to the monthly averages of the composite index of the international coffee exporters' association, the International Coffee Organization , a low of just over 100 US cents per pound (lb) in the 1970s, 1980s and mid-1990s was recorded in international trade in September 2001 41.17 US cents measured per pound; the twelve monthly means for 2005, however, recovered to values between 78.79 (September) and 101.44 (March) US cents per pound.

In addition to increased consumption, which led to a balanced market, hedge funds and other speculative investors, who have driven up prices on commodities and coffee exchanges , have contributed to the increase since late 2004 . The number of traded and outstanding commodity futures contracts has increased significantly.

Fair trade

Most of the time, the smallest portion of the price paid by the end consumer remains in the country of cultivation itself, and only a small portion of this remains with the coffee farmers and plantation workers. In fair trade , the classic product of which is coffee, attempts are made to improve this difficult economic situation for producers throughout the entire trade process.

Germany

The coffee industry in Germany is an oligopoly : six suppliers, including Tchibo and Aldi , share 85% of the market. The large German roasters are concentrated in the Hamburg and Bremen areas. The port of Hamburg is the largest import port for coffee in Europe, while the largest amount of coffee in Germany is handled in the city of Bremen via the ports of Bremen and Bremerhaven. Four of the largest coffee roasting plants in Germany are located in Bremen and the surrounding area.

| 44.9% | Taxes, duties, freight costs |

| 23.7% | retail trade |

| 17.8% | Traders and roasters |

| 8.5% | Plantation owner |

| 5.1% | Wages of workers |

| product | Quantity (in t) |

|---|---|

| Filter coffee (ground) | 261,650 |

| Whole coffee bean | 63,450 |

| Coffee pad | 48,650 |

| Instant coffee | 19,890 |

The proportion of coffee from certified sustainable cultivation was around 8% in 2014.

As a result of the drop in prices on the coffee market in 2001, the price of coffee fell to a level that had never been undercut in the previous 50 years: an annual average of just 3.28 euros had to be paid for 500 g of coffee in 2001. This “ coffee crisis ” had far-reaching consequences for coffee producers around the world .

On the basis of the Coffee Tax Act , roasted coffee and goods containing roasted coffee are taxed. A tax of 2.19 euros / kg is levied on roasted coffee and a tax of 4.78 euros / kg on soluble coffee. The annual income from the coffee tax in Germany amounts to around one billion euros. Recently, some manufacturers have started to add up to 12% maltodextrin, caramel and other carbohydrates to roasted ground coffee. While the manufacturers Kraft Foods and Tchibo justify this with taste reasons, this approach, together with roasting abroad, also offers companies considerable tax advantages.

Pricing

The quality ranking is based on the types of varieties in demand in the trade. There is a strong demand for Colombian Mild varieties with a broad spectrum of flavors.

The pricing is generally based on:

- economic aspects and quality criteria

- price formation on the world market

- the special trading structure

- multinational trade agreements and their effects

Yield gaps result from the difference between the maximum yield that can be achieved using what is biologically and technically feasible under optimal conditions on test stations and the actual yields in agricultural practice. The worldwide cultivation area varies due to the current raw material prices for coffee. While the acreage declined slightly in Brazil, it was expanded in the Dominican Republic , Costa Rica and Honduras . The largest increases in area were observed in Asia, particularly due to the very low wages in Vietnam .

Different intensities are used in coffee cultivation: a minimum of 1.9 tons per hectare in subsistence farming , 1.7 tons per hectare in semi-shade cultivation and 4.9 tons per hectare in cultivation with shade trees. Due to an opaque price and trade policy, African coffee cultivation stagnated for a certain time. In Rwanda and Burundi , coffee revenues fell sharply due to the civil wars, despite an export-oriented agricultural policy.

The coffee supply is economically an almost completely inelastic short-term supply curve. A long-term supply reaction has a time lag of up to eight years, since the optimum yield of a coffee plantation is only achieved during this period. The first harvest of a newly created plantation can only be made after three to four years at the earliest. The demand for coffee is also relatively inelastic. There is a slight and short-term price elasticity Note: for coffee between 0.1 and 0.2, since national drinking and eating habits determine consumption. Note:

International coffee agreements

A one percent increase in supply would therefore cause a four percent price drop. In order to regulate these effects, the trade was instrumentalized by means of international coffee agreements. In 1963 the first ICA (International Coffee Agreement) was made between producer and consumer countries and had the aim of compensating for price fluctuations on the world market . The ICA consisted of a set of rules consisting of export quotas and guide prices , which were adjusted according to the market situation.

In 1983 there were further price- quota agreements and intervention prices ; the quota volume was decided by a council at that time and was based on the total quota of the exporting countries. 85% of the world market was thus controlled by intervention prices. Countries with a low export and market share did not always adhere to the quota discipline, and there was a discrepancy between producing countries with a high proportion of cheap coffee and others with low proportions but high quality. Leap in innovation in coffee production (Costa Rica increased its coffee yields to 2.5 t / ha) give some countries production advantages and trigger cost competition. The trade structure in the coffee-producing countries is often state-controlled or regulated by aggregated trade. Since the foreign exchange proceeds for coffee were relatively high, this agricultural commodity was often the focus of national economic policy. In order to guarantee stable prices, the supply was often artificially reduced through state intervention . 50 countries in the third world were or are still heavily dependent on foreign exchange revenues from coffee exports, since 70% of coffee worldwide is produced as a "cash crop" in small-scale subsistence agriculture. The harvest of high-quality Arabica coffee requires farming methods ( labor intensity in Kenya for 850 kilograms of green coffee approx. 2900 man- hours ).

There are concentrations in the importing countries, so that in some countries up to 95% of total sales come from four large roasting plants. Oligopoly organizational structures can be found on both the producer and the sales side. In any case, the trading margin covers the high transformation costs. The import price elasticity as a net range is 0.3 in the Federal Republic of Germany and 0.7 as a single regression and 0.03 as a multiple regression. Coffee agreements clearly have a stabilizing effect on the market and are intended to ensure a moderate price level. If there is an oversupply, the producers try to export more to non-quota countries. In Brazil, the quota shares were partially topped up with low-quality Robusta coffee. If the surpluses cannot be sold, one looks for sales at dumping prices on the residual market. The Eastern Bloc countries of that time, such as the GDR , Poland and the USSR , received high-quality coffee too far below the world market price. In coffee production there is mostly a structural overproduction , partly due to the biological-technical progress in production and on the other hand due to the entry of new participants like Vietnam, which now ranks second among world producers due to the strong expansion of cultivation.

The ACPC ( Association of Coffee Producing Countries ) was founded in 1993, and in 1996 the 5th International Coffee Agreement was passed between 36 producer and 17 consumer nations. These countries are organized in the ICO ( International Coffee Organization ). Of the 43 billion US dollars in coffee sales in 1997, less than 30% went to the countries of origin of the raw material. The market gains from the low-price policy of coffee processors such as Kraft Foods , Nestlé , Tesco , Sara Lee and Starbucks were not passed on to the producers.

consumption

The Finns have the highest coffee consumption in the world, followed by Norwegians and Swedes. Each inhabitant of Finland consumed an average of almost 8.5 kg of coffee in 2009, which corresponds to a total of 1305 cups per year or 3.6 cups per day and person. The USA has the highest total consumption, in 2003 it was estimated at 1,216,477 tons (Finland: 59,301 tons). Converted to the individual resident of the USA, these numbers correspond to 4.2 kg, i.e. 646 cups per year (1.8 per day). These figures are based on data from the International Coffee Organization (ICO) after calculating imports minus re-exports.

On average, every German consumed 6.9 kg of coffee in 2013; that's equivalent to 2.6 cups of coffee a day. This makes coffee the most popular drink among Germans, ahead of beer.

In Switzerland, the average consumption in 2018 was 975 cups per person, in 2017 it was 1110 cups.

Preparation and consumption

The way the coffee is prepared changes depending on the culture, national customs or personal taste. To make the drink, the bean is roasted and ground. The degree of roasting and grinding depends on the type of preparation.

In the liquid preparation, he is infused with water, without any ingredient produced black coffee or black coffee . Most of the preparation methods use water just below the boiling point . If the water temperature is too low, the coffee tastes thin, old and sour; if the water is too hot, more bitter substances are released from the coffee powder and it tastes bitter and burnt. Preparation with water at room temperature is possible, but requires a much longer time of at least eight hours. Cold Brew is a young phenomenon that has only been included in the range of larger coffee chains internationally since 2015. You can even prepare coffee with ice-cold water: cold drip is a special form of cold brew . In this process, water is mixed with ice cubes and dripped onto the coffee powder over many hours.

- With direct infusion (familiar robber coffee , on goods also harvest coffee , people's coffee ), ground coffee is infused directly with heated, non-boiling water of around 91 ° C.

- In France, the method of pouring the mostly coarsely ground coffee into a plunger jug (also called French press or cafetière) is widespread. After a few minutes, usually three to five, the coffee grounds are pressed onto the floor with the help of a wire mesh. A newer variant of the press ram can is the AeroPress . It works on a similar principle, but separates the water from the coffee after the brewing process.

- When infusing a pot , almost boiling water is poured over mostly coarsely ground coffee in the pot. The coffee is then poured into the cup through a metal sieve that filters the coffee grounds.

- In the Austrian Austro-Hungarian Danube Monarchy , coffee was mostly boiled, brewed coffee was called "Karlsbader", after the " Karlsbader Kanne " , which was necessary for it .

- Coffee is also poured and drunk directly in the cup after most of the coffee powder has settled on the floor. Here stirs the ancient oracle technology , read from the coffee base .

- In filter coffee , which is widespread in Central Europe and North America , hot water is added drop by drop to the coffee powder in a coffee filter made of filter paper . The water temperature is usually between 90 ° C and 95 ° C. Mostly machines are used that are available in different sizes and price ranges. Very finely ground powder can be used for this application.

- A subspecies of filter coffee is the gush method . In contrast to the usual machine preparation, the hot water (between 90 ° C and 95 ° C) is not poured into the filter drop by drop, but the filter is filled with a surge of water once or several times using a kettle. Scientifically verifiable, this leads to a lower level of bitter substances, since coffee grounds and water come into better contact with one another. Formerly a common preparation, the gush method has been pushed back by the machines for convenience since the advent of machines.

- In Italy , for example , espresso is drunk, in which water is passed through the finely ground coffee under high pressure (around 9.5 bar) ( extraction ) and forms a foam from coffee bean oils, the crema .

- A similar method is the preparation with so-called coffee pods . Here, a prefabricated filter bag filled with finely ground coffee is placed in a special machine, in which the water is then pressed through. However, the pressure is lower than that of an espresso machine and usually cannot be varied. Nevertheless, a crema forms here too.

- A very common method of preparation for at home in Italy is the moka pot , which in Germany is also erroneously referred to as an espresso pot (although it cannot be used to make espresso). Here, the jug is heated on the stove, with hot water being pressed by steam pressure from the lower chamber of the jug through a puck of ground coffee into the upper part of the jug. The principle is similar to that of the espresso machine, but the result is significantly different due to the higher water temperature and the lower pressure (approx. 1.5 to 2 bar compared to 9.5 bar in the machine). Coffee from the Moka has more bitter substances than an espresso and, due to the lower amount of dissolved oils, also has no crema. The name Moka is not to be confused with the name Mocha .

- In Vietnam, Cà phê sữa is a coffee with sweetened condensed milk . This is also available with ice as Cà phê sữa đá . In addition to the well-known Robusta and Arabica species, the roasted coffee blend can also contain the Catimor and Chari species . It is a very dark coffee with a slightly nutty-chocolate taste and coarser grain. These coffee blends contain the varieties mentioned in different proportions and, more rarely, also contain Excelsa or Liberica beans. Because of the local idea of the coffee taste, these blends cover the majority of the coffee demand there. Mixtures containing the mentioned types of coffee, which are rather unknown on the world market, are only available as imported articles in Asian shops outside of Vietnam. Because of its very low caffeine content, Chari coffee is offered as a natural, gentle coffee that does not have to be decaffeinated.

- When preparing Turkish coffee (Turkey, Balkan countries; in Greece or in Greek restaurants, Greek coffee ), the very finely ground coffee is boiled with water and with or without sugar in a specially designed, slightly conical copper kettle, the so-called Ibrik or Cezve ( / ʤɛzvɛ ' /), also Dzezva or Djezva , or in Greek Briki . Various spices are sometimes added to this mocha , such as cinnamon , cardamom or rose water . Without filtering the coffee, the drink is served with the coffee grounds and poured into the cup; After the coffee grounds have settled, the still hot coffee is sipped without tilting the bowl too much so as not to stir up the coffee grounds.

- Soluble coffee , also known as "coffee extract", is a powdered drink that is dissolved in hot water and can be drunk without any further preparation steps. Soluble coffee is made by preparing coffee using one of the methods above and then removing the water from the prepared coffee.

Based on these basic preparations, there are hundreds of processes that use coffee. There are special coffee machines for many types of preparation . Machines for private households are already available for less than ten euros. Machines for the catering industry can be significantly larger and more expensive.

Malt coffee ( muckefuck ) is called coffee, but it contains malt and is not very similar to coffee in terms of taste. It is a food substitute (surrogate) for coffee and does not contain caffeine.

Internationally, most varieties are sweet. Many specialties combine coffee with alcohol, cocoa or dairy products. Salty coffee drinks are rarely prepared, but some people believe that a pinch of salt in the coffee filter would have a positive effect on the taste, or alternatively cause the brewing water to harden.

Roasted coffee beans can also be chewed. Different variants are available in stores, for example coffee beans coated with chocolate. Coffee is also ground for cakes, pies, ice cream and pralines.

The Tobacco Ordinance allows coffee to be added to tobacco products.

Effects of coffee

The positive effects of coffee seem to outweigh the negative. One study stated that the optimal amount was three to four cups of coffee per day. Thomas Hofmann, Director of the Institute for Food Chemistry at the Westphalian Wilhelms University , says: “The statement that coffee is generally harmful is no longer tenable today. (...) In the past, some negative effects of individual coffee ingredients were transferred to the overall coffee complex ”.

Many of the positive effects of coffee are attributed to the antioxidants it contains . According to a US study from 2005, by far the largest part of the physiological antioxidants consumed with daily food comes from coffee. However, this is less because coffee contains unusually large amounts of antioxidants than to the fact that Americans consume too few fruit and vegetables, but consume more coffee.

Green coffee contains a particularly large number of antioxidant substances . A study by German scientists shows that these antioxidants protect the cells: The researchers found that the daily consumption of three to four cups of a mixture of green and roasted coffee reduces oxidative DNA damage by 40% and thus improves cell protection. Scientists suspect that this effect explains the many positive effects coffee has on health.

More recent studies also reveal a genetic cause for the different consequences of coffee consumption. Depending on the gene variant, the alkaloid caffeine can be eliminated quickly or slowly , which in turn can have an impact on the risk of a heart attack .

In 2009, the German Green Cross summarized the various research results as follows: “The regular consumption of three, four or more cups of coffee has a positive influence on numerous organs and body functions. For some diseases, coffee even seems to have a clear preventive or protective effect. Basically, coffee does not have to be dispensed with in most cases for medical reasons. In individual cases, however, you should consult a doctor again. This is especially true for women who are pregnant. ”The caffeine in coffee is associated with slowing fetal growth and an increased risk of lower birth weight.

A comprehensive presentation of research results on the topic of coffee and health was published in the monograph Le café et la santé .

Caffeine is also absorbed (absorbed) sublingually through the oral mucosa , which is why the caffeine takes effect more quickly if the coffee is left in the mouth longer before swallowing. The same effect is achieved with chewing gum that contains caffeine. When it is absorbed into the blood via the rest of the digestive tract, the blood first passes through the liver, some of which is immediately filtered out again ( first-pass effect ).

Coffee contains caffeine as its main active ingredient. The following withdrawal symptoms were compiled in a review article: headache, exhaustion, loss of energy, decreased alertness, drowsiness, decreased satisfaction, depressed mood, difficulty concentrating, irritability and the feeling of not being able to think clearly. In some cases there were also flu-like symptoms. The symptoms set in twelve to 24 hours after the last caffeine consumption, peak after 20 to 51 hours and last about two to nine days. Even a small amount of caffeine leads to relapse.

Medical history

According to Madaus , the decoction of raw coffee beans was taken for intermittent fever , whooping cough , etc., and a Peretti coffee liqueur, a Ferrari syrup and an Essentia Coffeae were prepared . Roasted coffee was a dietary aid for diarrhea and various types of poisoning. From Haller's Medicin. Lexicon (1755) describes coffee as a stomach-tonic, wind-blowing, laxative, with the disadvantage of "heating up the blood", fatigue and nervous tremors; it can be used without milk against diarrhea caused by a cold. According to Hecker's practical medicine theory (1814), raw coffee has a tonic, nourishing and "wrapping" effect, Gentil praises it for catarrh , gout and suppressed menstruation, Grindel as a cinchona bark substitute for intermittent fever, but also nerve fever, atony of the digestive organs (diarrhea, atrophy, putride Fever) and to maintain strength. Delioux added 30-40 g of unroasted beans to 1/3 l of boiled water with lemon juice for intermittent fever. Audon recommended roasted coffee for intermittent fever, Lanzoni and Schulze for bilious diarrhea, Pringle for nervous disorders and periodic asthma, Hecker for gastrospasm , apoplexy , insomnia , headache, poisoning and stone diseases . Osiander often recommended coffee, Hufeland et al. a. as digestive. Clarus used strong coffee and a. for migraines and other neuralgia , if there was insufficient cerebral blood flow but no digestive disorder. Künzle mentioned the healing of lupus by washing with coffee water. Madaus concluded from his own experiments that fiber from the coffee bean accelerated the detoxification of caffeine via the urine, which is probably the reason for the better tolerance of “Turkish” coffee that is enjoyed with sediment. According to Kleine, chewing a coffee bean in bed in the morning helps with vomiting. Madaus also names unwanted effects such as ringing in the ears, headache, dizziness, neurasthenia , hemorrhoids and rosacea . According to Lewin, heavy coffee consumption leads to pruritus vulvae et ani , reduced sexual excitability, flickering in the eyes, amblyopia and temporary numbness. According to Samuel Hahnemann , coffee is medicinal, so mere consumption is harmful. After his pharmacology, he increases organ and sensory functions and helps u. a. with fever and severe labor. Homeopaths use Coffea when there is a lack of sleep through mental, also joyful excitement, headache and noise-sensitive pain. A home remedy uses heated coffee grounds in the foot bath for heel spurs .

Effects on the psyche

A ten-year study of 50,739 American women (mean age 63 years) examined the relationship between coffee consumption and the risk of depression. The women who were not depressed at the start of the study showed a lower risk of developing depression when they consumed more coffee . The caffeine in coffee can intensify symptoms of anxiety disorders . Conversely, reducing your caffeine intake can have a symptom-relieving effect.

Since caffeine blocks adenosine receptors, it indirectly leads to an increased release of dopamine . Dopaminergic stimulants (such as caffeine) promote the ability to concentrate , e.g. B. Methylphenidate used for ADHD treatment . However, as the amount of coffee consumed increases, the opposite effect occurs; symptoms of caffeinism also include poor concentration and hyperactivity. The mechanism of this effect has not yet been sufficiently clarified. The concentration- promoting effect could be made visible in the magnetic resonance tomograph , in particular the brain areas of the frontal lobes and the anterior cingulate gyrus , in which the short-term memory is located, became active.

Effects on Sleep

According to an article in Sleep magazine, it makes more sense to take many small sips of coffee throughout the day than to take a large cup of coffee in the morning in order to fully exploit the encouraging and concentration-promoting effects of coffee . In this way, the caffeine has a much more effective effect on the sleep centers in the brain. The strategy of spreading coffee consumption evenly over a longer period of time is particularly useful for people who work at night: It makes it easier for them to stay awake while maintaining their ability to concentrate.

Effects on metabolism

In a study by Trine Ranheim and Bente Halvorsen, an increase in cholesterol levels was found in individual cases after consuming unfiltered coffee. The filterable diterpenes Cafestol and Kahweol cause this effect.

Coffee can also reduce the absorption of the essential minerals calcium and magnesium and increase their excretion. It also lowers the level of magnesium in the blood. Coffee seems to be more beneficial to bone metabolism than harm.

Cancer risk

In 2020, a meta-analysis was published on 28 previous meta-analyzes on the relationship between cancer and coffee consumption, i. That is, 28 scientific articles were examined, each of which had examined several scientific publications on the topic. The authors found that moderate coffee drinkers are very likely to have a lower risk than non-coffee drinkers of developing liver cancer or cancer of the uterine lining . For the unborn child, however, coffee consumption during pregnancy is also harmful in terms of possible cancer diseases: There is clear evidence that children of women who drank a lot of coffee during pregnancy have an increased risk of developing acute lymphocytic leukemia . The meta-analysis found further possible positive effects for the coffee drinkers themselves. They may have a lower risk of developing malignant melanoma (black skin cancer), oral cancer, or throat cancer than non-coffee drinkers. Coffee drinkers are likely to have a higher risk of bladder cancer . The data situation is still uncertain for these types of cancer. It has also not yet been conclusively clarified “how the amount and regularity of consumption, the type of coffee and the type of preparation, e.g. B. the addition of milk or sugar ”, change the effect of coffee on cancer risk.

Researchers at Wayne State University in Detroit (USA) have found that regular coffee consumption appears to protect against "non-melanoma skin cancer (LMWHD)". The Women's Health Initiative collected clinical data and dietary habits from over 93,000 women. It turned out that there was an inverse relationship between coffee consumption and the risk of skin cancer: with every cup of coffee that was drunk, the incidence of LMWHD diseases fell by 1%. Women who drank six or more cups of coffee a day had a 30% lower risk of developing LMWHD than women who did not drink coffee. However, this relationship does not apply to decaffeinated coffee. The researchers suspect that caffeine's antioxidant properties are responsible for this. According to current data from Japan, caffeine can also significantly improve the effect of chemotherapy.

As in a number of other foods, the substance furan is found in coffee , which is suspected of promoting cancer. However, it has not yet been adequately researched whether long-term intake of small amounts of furan, for example via coffee, poses a health risk for humans. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment currently sees no evidence that furan contamination from food is a health concern. The International Agency for Research on Cancer looks after the evaluation of more than 1,000 studies by 23 experts "insufficient evidence of cancer risk" by coffee more, an article in the weekly newspaper "Die Zeit".

Decreased risk of high blood pressure

Coffee is believed to lower the risk of high blood pressure. A large meta-analysis showed a reduced risk of high blood pressure with long-term consumption of seven cups of coffee a day. However, the measured effect could be partly due to different cigarette consumption.

Heart disease and diabetes mellitus

Because of contradictory data available on this issue in 2005 by American researchers called CALM study ( C offee a nd L ipoprotein M etabolism study) conducted in which the effects of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee on heart, blood circulation and metabolism first time after the the high standards of a clinical trial . The surprising result: coffee containing caffeine had no negative effect on the measured parameters such as blood pressure , pulse rate , body mass index (BMI), blood sugar level , amount of insulin and various blood fat values ( total cholesterol , HDL cholesterol , LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B). In contrast, in the group who had drunk the decaffeinated coffee, the blood lipoprotein and free fatty acid levels - both risk factors for arteriosclerosis - increased significantly, and the level of LDL cholesterol ("bad cholesterol") was also frequent as a result elevated. However, decaffeinated coffee did not only have negative effects on all test subjects: in overweight people with a BMI of more than 25, but not in participants of normal weight, regular consumption also increased the amount of “good” HDL cholesterol by more than 50%. Two other large-scale studies, an American study of over 45,000 men and a Finnish cohort study of over 20,000 female and male subjects, clearly concluded that regular coffee consumption posed no risk of coronary or cerebral vascular disease. The authors of the Finnish study found the highest mortality even in men who did not drink coffee at all, and in women, too, the death rate fell continuously with increasing coffee consumption.

While no influence of coffee was found on blood sugar and insulin levels in the large-scale CALM study, researchers report from Duke University in Durham (USA) in the journal Diabetes Care that caffeine in combination with a meal in diabetes mellitus the Raised blood sugar levels by nearly 50% and insulin levels by 20%. The researchers concluded that caffeine further impaired the diabetics' already disturbed energy metabolism . However, the number of 14 study participants was very small, and pure caffeine was given in capsule form, not coffee (as a drink).

A large epidemiological study with more than 120,000 participants showed that men who drank more than six cups of coffee a day had a 54% lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, while the risk was reduced by 29% in women. The scientists were unable to definitively clarify which factors are responsible for this effect. On the one hand, ingredients of the coffee itself such as caffeine, potassium , magnesium or antioxidants can be considered, on the other hand, it could be that the habits of the heavy coffee drinkers differ from those of the other test subjects in ways that were previously unknown.

The finding that coffee reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes is also confirmed by a study from 2006 with almost 29,000 participants. Since both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee displayed the significant “diabetes protection effect” observed , the researchers concluded that the health-promoting effect is not due to the caffeine, but rather to the antioxidants, polyphenols or minerals in the drink in abundance .

According to the results of a study from 2006, the amount of caffeine in two cups of coffee should measurably reduce the blood flow to the heart muscle during physical exertion. This significantly reduces the positive effect of physical activity on the heart. This applies particularly to activities at high altitude or to people with coronary heart disease or atherosclerosis . Possible weaknesses of the study are the small number of subjects (18 participants), the dosage form of the caffeine in tablet form and the fact that the subjects were not allowed to drink coffee or other caffeinated drinks in the days before the test. Since there was no control group that was not weaned from caffeine, it cannot be ruled out that "habitual" coffee drinkers would have reacted less sensitively. It is also possible that caffeine develops different effects depending on its dosage form (for example in tablet form or as a hot drink).

In a study of 3987 participants, it was shown that three or more cups of coffee a day reduced the risk of chronic heart disease in Korean women.

Positive effects on the liver

For a specialist article (published on December 1, 2005), health and nutrition data from 9,849 volunteers in another large epidemiological study, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, were evaluated. Note: It was shown, among other things, that the number of chronic liver diseases was significantly lower in test subjects who had consumed more than two cups of coffee or tea a day . This effect, which the scientists ascribe mainly to caffeine, was only found in people with an increased risk of such diseases, for example alcoholics or overweight people.

kidney

In a study of 14,298 participants, people who consumed more coffee had a lower risk of developing chronic kidney disease.

heartburn

With moderate coffee consumption, heartburn can occur with the appropriate predisposition . However , studies have not found a connection with dyspepsia (indigestion). Either way, caffeinated coffee stimulates gastric acid production and contraction of the gallbladder .

Parkinson's and Alzheimer's Disease

The Parkinson's inhibiting effect of caffeine is discussed as a further positive effect , as the production of the neurotransmitter dopamine is stimulated. The onset of Alzheimer's disease could be delayed through regular consumption. In mice, when caffeine is added to drinking water, memory regeneration has been observed while reducing the buildup of amyloid beta , which is one of the causes of the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease.

libido

The effects of coffee consumption on potency are controversial. Coffee was alternately referred to as a drug that made people impotent or an aphrodisiac . However, in a human experiment in 1923, the researcher Amantea found that caffeine not only increased the desire for sexual intercourse, but also increased orgasm and increased the amount of ejaculate . A study from 2005/2006 showed that caffeine actually increased the sex drive in female rats . It remains doubtful whether this effect can also be observed in humans. According to the scientists involved in the study, the sexual pleasure-enhancing effects of caffeine - if present at all - would only occur in women who are not used to caffeine.

Refuted effects

No increase in blood pressure

In 2003, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the United States withdrew a recommendation that patients with high blood pressure should drink a moderate amount of coffee. Source? The Harvard School of Public Health in Boston supported this new assessment: In the Journal of the American Medical Association , a group of scientists presented a study with data from 156,000 women. A connection between habitual coffee consumption and high blood pressure has not been found.

drainage

In the press, but also by some doctors, it is often claimed that coffee removes water from the body and should therefore not be added to the fluid intake. However, this is only the case to a limited extent. A study in which twelve subjects who had been abstinent from caffeine for five days were given three cups of coffee twice a day (a total of 642 mg caffeine / day) over several days, showed a mean decrease in body weight of 0.7 after 24 hours kg and a reduction in total body water by 1.1 kg (measured with bio-impedance measurement ). However, a statement cannot be made about the fluid supply status of a person solely on the basis of the total body water amount, since the water, as in this case, can come from the extracellular space . With continued long-term coffee consumption, compensation mechanisms, such as an increase in the plasma vasopressin level and the osmolality of the urine, become active. An increased loss of fluids as a result of coffee only occurs once.

The caffeine contained in coffee has a diuretic effect. However, if coffee is consumed regularly and in similar quantities, is there no increased diuresis or natriuresis source? due to the increased level of various compensation mechanisms (escape phenomenon). According to the current state of research, coffee is therefore regarded as part of the body's water supply and can be treated like any other drink in the fluid balance.

Ingredients of coffee

A cup with 125 ml filter coffee contains around 80–120 mg caffeine and has a pH value of 5. Coffee is therefore slightly acidic. Some types of coffee also contain the β-carbolines Harman and Norharman in physiologically effective amounts, which can contribute to the psychoactive effect by inhibiting monoamine oxidase , among other things .

The average ingredients of Arabica coffee based on dry matter are given in the following table:

| substance | Green coffee (in%) |

Roasted coffee (in%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sucrose | 8.0 | 0 |

| Polysaccharides | 46.0 | 35.0 |

| lignin | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Fats | 16.0 | 17.0 |

| Proteins | 11.0 | 7.5 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 6.5 | 2.5 |

| caffeine | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Trigonelline | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ash | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| Caramelization, condensation products |

- | 28.5 |

Caramelization and condensation products are substances that are created during roasting and determine the aroma, brown color and taste. Most of these substances arise from Maillard reactions , which are complex reactions between reducing sugars and amino acids (from the proteins present in coffee).

About 40 volatile compounds probably contribute to the coffee aroma , of which 2-furfurylthiol , 4-vinylguaiacol , acetaldehyde , propanol , alkylpyrazines , furanones , methylpropanol and 2-methylbutanal / 3-methylbutanal are the typical components.

Coffee leftovers as a household item

- After brewing, cold coffee or the used coffee powder can still be used as garden fertilizer because of its high organically bound nitrogen content . Its high content of potassium , phosphorus and other minerals is good for plant development.

- Dry coffee grounds or sprayed coffee are environmentally safe pesticides for snails, but they are also likely to harm beneficial insects.

- In Meyers encyclopedia (1888), we read: "You used coffee grounds also for cleaning the chamber pots and the sweeping brown painted floors. If the coffee grounds are boiled with soda solution , a brown precipitate is obtained by adding alum to the filtered liquid, which can be used as paint. When charred, the coffee grounds give a kind of carbon black. The smell that develops when the coffee is brewed excellently conceals the foul smells of freshly whitewashed lime walls, freshly painted doors, when clearing fertilizer pits, in nurseries etc. ”(the“ foul smell ”of paints and varnishes came from the linseed oil varnish , which smelled rancid ).

- Reading coffee grounds is used in popular spiritism to tell fortune about the future and is called coffee romance .

Museums

In 1994 the Nova Delta Coffee Museum opened in Campo Maior , in the Portuguese region of Alentejo . It is part of the European Route of Industrial Culture and was considered the first and possibly only museum in Europe dedicated exclusively to coffee.

In 2003, the coffee museum opened on the ground floor of the annex building of the Austrian Society and Economic Museum in the 5th district of Margareten in Vienna .

Another small coffee museum is located on the 3rd floor of the historic Leipzig coffee house Zum Arabischen Coffe Baum .

See also

literature

- Bon, ex cujus fructu potus Coffée conficitur. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 4, Leipzig 1733, columns 534-545.

- Peter Albrecht: Coffee. On the social history of a drink (= publication [s] of the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum. 23). Braunschweig 1980, OCLC 1000530472 .

- Peter Albrecht: Drinking coffee as a symbol of social change in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. In: Roman Sandgruber , Harry Kühnel (Ed.): Enjoyment & Art. Coffee, tea, chocolate, tobacco, cola. Innsbruck 1994, ISBN 3-85460-108-5 , pp. 28-39.

- Stewart Lee Allen: Devilish stuff. On an adventurous journey through the history of coffee. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-593-37290-8 .

- Heidrun Alzheimer : Coffee - Consumption, Culture, Commerce. Booklet accompanying the exhibition of the same name in the Museum Malerwinkelhaus Marktbreit, March 20 - October 24, 2004 (= series of publications by the Museum Malerwinkelhaus. 4), Marktbreit 2004, DNB 971848890 .

- Daniela U. Ball (Ed.): Coffee in the mirror of European drinking habits. Coffee in the Context of European Drinking Habits. Johann Jacobs Museum, Zurich 1991, ISBN 3-906554-06-6 . (German English.)

- Mary Banks: Coffee. The black passion. Bindlach 1999.

- Hans Becker , Volker Höhfeld , Horst Kopp : Coffee from Arabia. The change in the meaning of a global economic good and its settlement-geographical consequence on the dry line of ecumenism. (= Geographic knowledge. Scriptures for research and practice. Issue 46). Wiesbaden 1979.

- Rolf Bernhardt, Simone Hoffmann: The world of coffee . Umschau, Neustadt an der Weinstrasse 2007, ISBN 978-3-86528-604-8 .

- Gérard Debry: Le café et la santé. John Libbey Eurotext, Paris 1993, ISBN 2-7420-0025-9 .

- Viviane Deak, Yvonne Grimm, Christiane Köglmaier-Horn, Frank-Michael Schäfer, Wolfgang Protzner: The first coffee houses in Würzburg, Nuremberg and Erlangen. In: Wolfgang Protzner, Christiane Köglmaier-Horn (Ed.): Culina Franconia. (= Contributions to economic and social history. 109). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-515-09001-8 , pp. 245-264.

- German Coffee Association: Fascination with coffee. Bucher Verlag, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7658-1879-0 .

- Oskar Eichler: Coffee and caffeine. 2nd Edition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin / Heidelberg / New York 1976, ISBN 3-540-07281-0 .

-

Ulla Heise : coffee and coffee house. A bean makes cultural history. Komet, Cologne 1996 and 2005, ISBN 3-89836-453-4 .

- Ulla Heise: coffee and coffee house. The history of coffee. Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-458-34495-0 .

- Tobias Hierl, Johanna Wechselberger: The coffee book. For beginners, professionals and freaks . 3. Edition. Braumüller, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-99100-045-7 .

- Ernesto Illy: From the bean to the espresso. In: Spectrum of Science. May 2003, ISSN 0170-2971 , pp. 82-87.

- Gerhard A. Jansen: Roasting coffee. Magic - Art - Science. Physical changes and chemical reactions. SV Corporate Media, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-937889-52-3 .

-

Heinrich Eduard Jacob : legend and triumph of coffee. The biography of a world economic material . Rowohlt, Berlin 1934.

- extended new version: Rowohlt, Hamburg 1952; Paperback edition: Rowohlt, Reinbek 1964.

- New edition under the title coffee. The biography of a world economic material . Oekom Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-86581-023-3 (with an update of the coffee world from the 1950s to the 2000s by Jens Soentgen ).

- Martin Krieger : Coffee. History of a luxury food. Böhlau / Cologne et al. 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20786-1 .

- Peter Lummel (Ed.): Coffee. From smuggled goods to lifestyle classics. Three centuries of Berlin coffee house culture. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-930863-91-X .

- Hans Gerhard Maier: Chemical aspects of coffee. In: Chemistry in Our Time . Volume 18, Issue 1, 1984, ISSN 0009-2851 , pp. 17-23.

- Fritz Maritsch, Alfred Uhl: coffee and tea. In: Sebastian Scheerer, Irmgard Vogt, Henner Hess (eds.): Drugs and drug policy. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1989, ISBN 3-593-33675-8 (also as a PDF ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Addiction Research ( Memento from February 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive )).

- Mark Pendergrast : Coffee. How a bean changed the world . Edition Temmen , 2001, ISBN 3-86108-780-4 .

- Bernhard Rothfos: Coffee - The Production. 2nd Edition. Gordian-Max Rieck GmbH, Hamburg 1982, ISBN 3-920391-06-3 .

- Bernhard Rothfos: Coffee - Consumption. Gordian-Max Rieck GmbH, Hamburg 1984, ISBN 3-920391-07-1 .

- Jürgen Schneider : Production, trade and consumption of coffee (15th to the end of the 18th century). In: Hans Pohl (Ed.): The European discovery of the world and its economic effects on pre-industrial society, 1500-1800. Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-515-05546-0 , pp. 122-137.

- Antoinette Schnyder von Waldkirch: How Europe discovered coffee. Travel reports from the Baroque period as a source of the history of coffee. Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-906554-02-3 .

- Dirk Selmar, Gerhard Bytof: The secret of a good coffee - Biochemical basics of post-harvest treatment. In: Biology in Our Time . Volume 38, Issue 3, 2008, ISSN 0045-205X , pp. 158-167.

- Cornelia Teufl, Stephan Clauss: Coffee . Zabert Sandmann, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-89883-077-2 .

- Hans Jürgen Teuteberg : Coffee. In: Thomas Hengartner , Christoph Maria Merki (Ed.): Luxury foods. A cultural story. Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2001, pp. 91–132.

Movies

- Black gold. Documentary, 78 min., USA, 2006, written and directed by Marc Francis and Nick Francis. Movie review:

- Bitter harvest. The high price of cheap coffee. Television report, Germany, 2013, 30 min., Script and director: Michael Höft, production: HTTV, NDR , series: Die Reportage. First broadcast: February 15, 2013 at NDR, summary from NDR.

- Cafe Rebeldia. Documentary, 75 min., Mexico, 2012, written and directed by Jan Braunholz, summary

Web links

|

Further content in the sister projects of Wikipedia:

|

||

|

|

Commons | - multimedia content |

|

|

Wiktionary | - Dictionary entries |

|

|

Wikisource | - Sources and full texts |

|

|

Wikiquote | - Quotes |

- Coffee tradition association, portal to coffee history

- German Coffee Association - information on cultivation, processing and trade

- General Association of the German Insurance Industry: "Goods information. Coffee, green coffee ” - also includes goods knowledge

- Vienna Coffee Museum and Coffee Competence Center - information about coffee

- KaffeeWiki - German-language wiki about espresso, coffee and machines

- Daniel Lingenhöhl: 10 surprising facts about coffee in the spectrum of science

- ICA International Coffee Agreement 2001. (PDF; 110 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Adaba: Austrian pronunciation dictionary. Austrian pronunciation database. Research Center for Austrian German, accessed on April 8, 2020 .

- ^ Wilhelm Viëtor : German pronunciation dictionary. Edited by Ernst A [lfred] Meyer. OR Reisland, Leipzig 1921.

- ↑ Austrian dictionary . 35th edition. Österreichischer Bundesverlag / Jugend & Volk, Vienna 1979.

- ^ Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm : German Dictionary. Lfg. 1 (1864), Volume V (1873), Col. 21, line 47.

- ↑ a b c coffee. In: Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: German dictionary. Volume 11, Col. 21.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pfeifer (Ed.): Etymological Dictionary of German. dtv, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-423-03358-4 , p. 607.

- ↑ Aaron P. Davis, Helen Chadburn, Justin Moat, Robert O'Sullivan, Serene Hargreaves, Eimear Nic Lughadha: High extinction risk for wild coffee species and implications for coffee sector sustainability . In: Science Advances . Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019, doi : 10.1126 / sciadv.aav3473 .

- ↑ Ulla Heise : Coffee and Coffee House. The history of coffee. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-458-34495-0 , p. 18 f.

- ↑ Heinrich Eduard Jacob : Legend and triumph of coffee. The biography of a world economic material. Rowohlt, Berlin 1934, p. 9 ff.

- ^ Ignaz Denzinger: First coffee bar in Würzburg. In: Archives of the Historical Association of Lower Franconia and Aschaffenburg. Volume 9, Issue 2, 1847, p. 161 f.

- ↑ Viviane Deak, Yvonne Grimm, Christiane Köglmaier-Horn, Frank-Michael Schäfer, Wolfgang Protzner: The first coffee houses in Würzburg, Nuremberg and Erlangen. In: Wolfgang Protzner, Christiane Köglmaier-Horn (eds.): Culina Franconia (= contributions to economic and social history. Volume 109). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-515-09001-8 , pp. 245-264, here: p. 248.

- ^ Fritz Maritsch, Alfred Uhl: Coffee and tea. In: Sebastian Scheerer, Irmgard Vogt, Henner Hess (eds.): Drugs and drug policy. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / New York 1989, ISBN 3-593-33675-8 (also as a PDF ( Memento from September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) on the website of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Addiction Research ( Memento from February 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Antoinette Schnyder von Waldkirch: How Europe discovered coffee. Travel reports from the Baroque period as a source of the history of coffee. Jacobs Suchard Museum, Zurich 1988, ISBN 3-906554-02-3 , p. 38.

- ^ Jürgen Schneider : Production, trade and consumption of coffee (15th to the end of the 18th century). In: Hans Pohl (Ed.): The European discovery of the world and its economic effects on pre-industrial society, 1500-1800. Steiner, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-515-05546-0 , pp. 122-137, here: p. 122.

- ↑ Ulla Heise: Coffee and Coffee House. The history of coffee. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-458-34495-0 , p. 43 f.

- ^ Peter Albrecht: Coffee. On the social history of a drink. (= Publication by the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum. Volume 23). Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum für Geschichte u. Volkstum, Braunschweig 1980, p. 42.

- ^ Annerose Menninger: Enjoyment in cultural change. Tobacco, Coffee, Tea, and Chocolate in Europe (16th – 19th Century). Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08624-2 , pp. 320-322.

- ^ Annerose Menninger: Enjoyment in cultural change. Tobacco, Coffee, Tea and Chocolate in Europe (16th – 19th Centuries). Steiner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-515-08624-2 , pp. 89 and 323-327.

- ^ Jürgen Schneider : Production, trade and consumption of coffee (15th to the end of the 18th century). In: Hans Pohl (Ed.): The European discovery of the world and its economic effects on pre-industrial society, 1500-1800. Steiner, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-515-05546-0 , pp. 122-137, here: pp. 122 and 129.

- ↑ See also Oskar Enzfelder: Wieden: Naming of the Johannes-Diodato-Park. On the website of APA-OTS, a subsidiary of APA - Austria Press Agency .

- ^ Karl Teply: The introduction of coffee in Vienna. Volume 6. Association for the History of the City of Vienna, Vienna 1980, p. 104; quoted in: Anna Maria Seibel: The importance of the Greeks for economic and cultural life in Vienna. P. 4, available online at: http://othes.univie.ac.at/2016/ (as .pdf).