hemorrhoids

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| K64 | Hemorrhoids Includes: hemorrhoidal nodules, varices of the anus or rectum. Excludes: as a complication in: childbirth or the puerperium (O87.2) or pregnancy (O22.4) |

| K64.0 | 1st degree hemorrhoids: hemorrhoids (bleeding) without prolapse |

| K64.1 | 2nd degree hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoids (bleeding) with prolapse when pressed, retract spontaneously |

| K64.2 | 3rd degree hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoids (bleeding) with prolapse when pressing, do not retract spontaneously, manual repositioning |

| K64.3 | Grade 4 hemorrhoids: Hemorrhoids (bleeding) with prolapse, manual repositioning not possible |

| K64.4 | Skin tags as a consequence of hemorrhoids |

| K64.5 | Perianal vein thrombosis |

| K64.8 | Other hemorrhoids |

| K64.9 | Haemorrhoids, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Hemorrhoids , even hemorrhoids called ( ancient Greek αἷμα haima "blood" and ῥεῖν rhein "flow"; outdated designations blind wires , gold wires , gold wires ) are arterio venous vascular cushions , the ring of the rectal mucosa are applied and the precise closure of the anus serve. These are varicose enlargements of the veins of the rectum in the area of the sphincter muscles of the anus. When people speak of hemorrhoids , they usually mean enlarged or deepened hemorrhoids in the sense of a hemorrhoid disease that cause symptoms. These complaints are mainly repeated anal bleeding and anal oozing, excruciating itching and stool smear .

Symptomatic hemorrhoids are one of the most common diseases in the western world, but are largely taboo in society . It is a disease of old age. Hemorrhoids before the age of 35 are rare. The causes of the disease are still largely unexplained. Symptomatic hemorrhoids are a progressively progressive disease that is divided into four degrees of disease. Because of its widespread use, the diagnosis of 'hemorrhoidal disease' is often made very lightly and often by those affected. Some much more serious illnesses are characterized by very similar symptoms.

Hemorrhoidals , which are mainly ointments and creams for the treatment of a hemorrhoidal disease, can at best relieve the symptoms. It is not possible to cure or stop the progression of the disease. With basic therapy , at least the progression of the disease can be slowed down. A cure is only possible through surgical interventions . In the early stages of the disease, these interventions can be carried out on an outpatient and minimally invasive basis. Far advanced hemorrhoid diseases can only be cured by an operation with an inpatient hospital stay. In many cases, those affected only seek medical treatment when the pain and discomfort outweigh the feeling of shame .

Anatomy and function of the hemorrhoidal plexus

The hemorrhoidal plexus , also called corpus cavernosum recti or plexus haemorrhoidalis superior , is a broad-based, spongy, arteriovenous vascular cushion that lies in a ring under the mucous membrane of the end of the rectum (the submucosa of the distal rectum) and usually directly above the border line ( linea dentata ) Anal canal and rectum ends. This erectile tissue is held in place by the canalis ani muscle and elastic fibers in the upper anal canal.

The corpus cavernosum recti was formerly called the zona haemorrhoidalis . This designation has been deleted from the anatomical nomenclature because haemorrhoidalis denotes a pathological condition.

Arterial supply

The hemorrhoidal plexus is part of the continence organ and is supplied arterially via the superior rectal artery . The vascular cushion is designed in a ring shape, but the anatomical position of the mostly three blood-supplying branches of the superior rectalis artery emphasizes the cushions, the main hemorrhoidal node , in three sectors, namely in anatomical position 3 (on the left as seen from the patient), 7 and 11 a.m. (on the right as viewed from the patient). According to the definition of the lithotomy position, the 6 o'clock position always points to the tip of the tailbone , regardless of the examination position. Secondary nodes can be assigned to the main nodes . The 7 o'clock main node has two secondary nodes at 9 and 6 o'clock and the 3 o'clock main node has two secondary nodes at 1 and 4 o'clock. The 11 o'clock major knot rarely develops minor knots; if then at 12 o'clock. An adult human therefore normally has three major hemorrhoidal nodes and four, maximum five secondary hemorrhoidal nodes. The hemorrhoidal nodes (hemorrhoids) develop during puberty and are not a pathological finding, but normal. Although the pathological changes in this erectile tissue have been known to mankind as haemorrhoidal disease for millennia, the haemorrhoidal plexus - the normal anatomical case - and its function were only discovered in the middle of the 20th century. The superior rectal artery can have individual variations and form, for example, up to five terminal branches that then feed the hemorrhoidal plexus.

Venous outflow

The venous drainage of the hemorrhoidal plexus leads through the internal and external sphincter muscles ( sphincter ani internus or externus ), which together with the hemorrhoidal plexus and other muscular, neural and epithelial structures form the continence organ. The hemorrhoidal plexus closes the anal canal from the inside. To do this, the hemorrhoidal nodes interlock in a star shape. This results in the fine sealing of the anus , which is very important for anal continence , i.e. the ability to hold back stool for a certain time or to trigger the elimination process willingly. The share of the corpus cavernosum recti in continence performance in the resting state is around 10 to 15%. If the internal sphincter is tense, the venous outflow is restricted and the hemorrhoidal plexus fills with blood. This prevents the passage of feces and intestinal gases . In this function, the corpus cavernosum recti also plays an important role in the development of human socialization .

Mechanism of the anal canal closure

The sphincter muscles of the anus would not be able to close the anal canal on their own. Even with maximum contraction of these spinal muscles, an opening about 10 mm in diameter would remain, which can only be closed by the canalis ani muscle and the corpus cavernosum recti on it.

If the nerve endings of the rectum signal to the brain that there is enough feces in the rectal ampulla of the rectum, the need to defecate arises. The internal sphincter then relaxes and blood drains from the hemorrhoidal plexus, which opens the lock and allows feces to be excreted. This process happens involuntarily . By contrast, bowel movements can be controlled arbitrarily via the external sphincter, which is supported by the pelvic muscles.

The corpus cavernosum recti contains no arterioles and no venules . It is a direct vascular connection between the branches of the supplying superior rectalis artery and the draining veins, without capillaries (functional circulation). The arterial terminal branches open directly into large spongy ( lacunar ) vessels. These vessels in turn divert the blood in a kind of rope ladder system into the upper, middle and lower rectal veins ( vena rectalis superior , media and inferior ). This vascular structure (arterio-venous "short circuit") enables the build-up of considerable pressure in the blood vessels . On the surface of the hemorrhoidal plexus there is an arterial vascular system that branches into smaller blood vessels and radiates into the spaces between the plexus. This vascular system supplies the corpus cavernosum recti itself with blood (nutritive circulation; nutritive = 'serving for nutrition'). Hemorrhoids are cherry red because of the arterial blood supply. Only in the case of a hemorrhoidal disease can a hemorrhoidal node displaced in front of the anus change its color due to jamming. The congestion of blood then turns it blue-red and apparently venous.

Definitions and demarcations

According to the guidelines of the German Society for Coloproctology , the term 'haemorrhoids' should only be used if the corpus cavernosum recti is enlarged ( hyperplasia ) and only if the haemorrhoids cause discomfort, it should be referred to as 'haemorrhoids' or 'symptomatic haemorrhoids'. However, these clear definitions of terms are largely disregarded in many publications and especially in everyday language. The anatomical term hemorrhoids is mostly used as a synonym for a hemorrhoidal disease .

Specifically, in the Swiss and English literature the terms inner 'are (internal) and outer' (external) hemorrhoids (haemorrhoids) used. The dentate line is used as the borderline to differentiate . "Outer hemorrhoids" arise below ( distal or aboral ) the dentate line , "inner" above ( proximal or oral ) of it. "Outer hemorrhoids" are diseases of the venous plexus ( plexus haemorrhoidalis inferior ) lying under the skin around the anus . In Germany, the terms 'internal' and 'external' hemorrhoids are not recommended. An "external hemorrhoid" is than perianal , Analthrombose, perianal thrombosis, Analvenenthrombose, perianal hematoma referred perianal hematoma or spurious hemorrhoid. Perianal thromboses are painful blue-black bruises caused by a ruptured perianal vein.

Hemorrhoids are not " varicose veins (varices) of the anus". Varicose veins are visible, tortuous, elongated and dilated superficial, large veins. Rectal varices, which can develop especially in patients with portal hypertension , are a separate clinical picture that must be distinguished from hemorrhoids or hemorrhoidal disease. Despite these anatomical and pathological issues, the ICD-10 system for the classification of diseases and related health problems listed 'hemorrhoids' under the code I84 and assigned them to diseases of the veins, lymph vessels and lymph nodes, not elsewhere classified (I80 – I89) . Under I84, among others, the clinical picture of rectal varicose veins found (I84 varices of the anus or rectum ), perianal thrombosis (I84.3 external thrombosed hemorrhoids ) and skin tags as a successor state of hemorrhoids (I84.6) (actually a subsequent state of perianal). In the literature, even in the 21st century, the misnomer 'varicose veins' is often used. The error can be found, for example, in books on medical officer examinations. Since 2013, hemorrhoids have been listed under K64 and thus in the Digestive System Diseases chapter.

Hemorrhoids are fed by arteries. If they are injured, bright red - that is, arterial - blood emerges from the arteriovenous anastomoses of the vascular chambers of the anorectal mucosa. In contrast to this, the blood of the much less bleeding perianal thrombosis ("external hemorrhoids"), which comes from the inferior hemorrhoid plexus , is dark red, that is, of venous origin.

distribution

Hemorrhoid disorders usually develop between the ages of 45 and 65. Women and men are affected about equally often. Hemorrhoids before the age of 20 are unusual. Hemorrhoids are a very common disease, which is why they are sometimes referred to as a "widespread disease". In Germany there are around 3.5 million cases that are treated every year. Around 50,000 operations are carried out. It is estimated that there are approximately 1,000 hemorrhoid-related visits to the doctor per 100,000 people in western industrialized nations, or 1% of the population per year. In addition, there is a high proportion of self-diagnoses and self-treatment that can hardly be recorded.

There are very different information about the number of new cases ( incidence ) and the frequency of the disease ( prevalence ): In numerous specialist articles and specialist books, very high figures are given for the frequency of symptomatic hemorrhoids, which are in the range of 50% of the population. Symptomatic hemorrhoids are classified by some authors as "the most common disease of the rectum". There is also information that around 70 to 80% of the population would experience hemorrhoidal complications in the course of their life. However, these figures are not based on epidemiological data, but on estimates by experts. The few available epidemiological studies show that the frequencies are considerably lower. One reason for this is that a large number of anal complaints, such as anal eczema , are obviously attributed to symptomatic hemorrhoids.

There are also only a few studies on the prevalence of hemorrhoids. The authors of the guideline for hemorrhoids of the German Society for Coloproctology from July 2008 even come to the conclusion: There are no valid epidemiological studies on the prevalence of hemorrhoids. The existing studies vary considerably in their results, which is primarily due to the study design , but also to the problems involved in determining the prevalence. Because of their feelings of shame, many patients initially 'sit out' the suffering, try self-treatment or follow unqualified recommendations. A weak point of previous studies is that the patients were asked orally or in writing about symptoms of hemorrhoidal disease - which can, however, also occur with other diseases. A medical examination is essential for reliable data.

In one study, for example, the medical files of a colectal ward - a ward that deals with diseases of the colon and rectum - were evaluated. The authors of the study determined a prevalence of 86% for asymptomatic and symptomatic hemorrhoids. This study was carried out on a very special, selected group of patients . Systematic errors cannot therefore be ruled out. In 1990, a meta-analysis was published that evaluated data from the National Health Interview Survey , the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the National Disease and Therapeutic Index of the United States and the Morbidity Statistics from General Practice from England and Wales. The authors found a prevalence of 4.4%, which corresponds to 10 million US citizens who suffer from hemorrhoids. The maximum frequency was in the age range from 45 to 65 years. In the studies mentioned above, the hemorrhoids were not classified into symptomatic or asymptomatic, nor were they classified according to their stages.

In September 2011 the results of a prospective study from the years 2008 and 2009 were published in which 976 patients in Austria were examined for hemorrhoids as part of a colonoscopy for cancer prevention at four different clinics. The hemorrhoids were classified according to a standardized system. A total of 380 patients (38.9%) were diagnosed with hemorrhoids. If only the 380 patients are considered, the majority (72.9%) had hemorrhoids in stage 1, in 18.4% in stage 2, in 8.2% in stage 3 and in only 2 patients (= 0, 5%) in stage 4. Almost half (44.7%) of patients with diagnosed hemorrhoids complained of symptoms associated with their hemorrhoids. Accordingly, 55.3% were without complaints. For all 976 patients in the study, 17% complained of symptomatic hemorrhoids.

In another study, 548 patients with unclear symptoms in the abdomen and / or anus were questioned and then examined proctologically and colonoscopically. 63% of the patients believed they had a haemorrhoidal disease, 34% did not believe this and the rest did not answer. However, only 18% and 13% of these patients were found to have hemorrhoids. The authors of the study conclude that hemorrhoids are suspected and treated too often.

In an Italian study from 2010, 116 patients were examined for asymptomatic and symptomatic hemorrhoids prior to their kidney transplantation . 70.6% had no hemorrhoids. First-degree hemorrhoids were found in 24% and second-degree hemorrhoids in 5.4%. No patient had third or fourth degree hemorrhoids. After the transplant, 22.4% of 116 patients developed third and fourth degree hemorrhoids. This was particularly the case with patients who had previously exhibited hemorrhoids or who gained body weight rapidly after the transplant. The study's authors suggest that post- transplant immunosuppressive therapy may play an important role in worsening hemorrhoids.

African Americans are significantly less affected than whites. In underdeveloped countries, hemorrhoids are extremely rare.

Disease origin and course

There are no reliable data from clinical studies on the causes ( etiology ) of the development of a hemorrhoidal disease. The few existing studies provide partly contradicting results. A large number of different factors are sometimes controversially discussed.

While the etiology is largely unclear, the origin and development ( pathogenesis ) is largely certain. Hemorrhoids are the result of the breakdown of muscular and elastic components, which causes a pathological displacement and enlargement of the corpus cavernosum recti in the direction of the anus (distal). The shift disrupts the anatomical structure of the anal canal. Especially during bowel movements, shear forces act on the vessels of the corpus cavernosum recti , which can lead to damage to the vessel walls and circulatory disorders in the vascular plexus. The bleeding that is often observed comes from arterial vessels on the surface of the plexus and results from mechanical stress.

etiology

The causes of enlargement and prolapse of the hemorrhoidal plexus are still largely unclear. A variety of triggers are controversial. Sufficiently reliable data is not available and the data available is often contradictory. Bad nutrition, disturbed defecation behavior, functional disorders that affect the rectum and anus, familial predispositions and an increase in pressure in the abdomen are seriously discussed .

Many authors attribute an important role to the defecation behavior in the development of a hemorrhoidal disease. Too early and compulsive abdominal cramping during bowel movements causes small-volume stool portions and the resulting increased stress on the hemorrhoidal plexus when defecating. Both factors of unphysiological defecation can influence each other. Too small stool volumes automatically lead to more frequent stool movements with increased use of the abdominal press, so that the feces in the rectum are pressed against the hemorrhoidal cushions, which are still filled with blood. The blood evacuation of the vascular cushions cannot take place arbitrarily, but requires the rectoanal reflex, which does not occur in the 'compulsive' defecation. The repeated voluntary pressure on the hemorrhoidal cushions causes their increasing displacement outwards.

In several studies a clear connection between chronic constipation (constipation) and hemorrhoids could be established. Constipation, in turn, can lead to incorrect defecation behavior. Other authors question that constipation promotes hemorrhoidal disease.

An incorrect diet with too little fiber is held responsible for the development of hemorrhoidal diseases. The basis of this theory is essentially an epidemiological study from 1977, in which it was found that Africans eat a diet rich in fiber and are considerably less likely to develop some diseases of civilization than Europeans and Americans who mainly eat low-fiber foods. In fact, hemorrhoids are extremely rare in rural Africa. Some studies show positive effects on a high-fiber diet. However, some authors question the sense of a high-fiber diet, as this results in large amounts of stool, which in turn causes more frequent bowel movements and thus increased stress on the hemorrhoidal cushions.

In a study from 2011, a correlation between the body mass index (BMI) and the frequency of hemorrhoids could be determined. The mean BMI in patients with hemorrhoids was 27.04 and in patients without 26.33 kg / m². The difference is relatively small, but still statistically significant . In this study, this was the only independent risk factor for hemorrhoids while gender, education, marital status , pregnancy and type of delivery (vaginal or cesarean ) were without significance. According to this study, age was the most significant risk factor.

A French study of over 2000 patients from 2005 identified a spicy diet, recent acute constipation, increased alcohol consumption and physical exertion as risk factors for hemorrhoidal disease . On the other hand, obesity was not a risk factor in this study. Stress even had a protective function.

The influence of pregnancy on the development of hemorrhoids is discussed very controversially. Basically, hormonal changes and the space requirements of the fetus can lead to symptoms and complaints in the anal area during pregnancy . There are many articles in the specialist literature with statements regarding an accumulation of haemorrhoidal diseases during pregnancy. However, there are no evidence-based studies on this aspect. Some proctologists question the correct diagnosis and suspect possible confusion with skin tags . In addition, most women are symptom-free a few weeks after giving birth without treatment for the "hemorrhoids". In many cases it appears to be a perianal thrombosis ("external hemorrhoids") or anal fissures . In a French study, a third of the young mothers were diagnosed with a perianal thrombosis or an anal fissure. One study found an increase in “symptomatic hemorrhoids” in the first few weeks after birth. However, after 8 to 24 weeks the symptoms disappeared again. This course of the disease also corresponds more to that of a perianal thrombosis than a hemorrhoidal disease.

The genetic predisposition in the form of a congenital connective tissue weakness is often cited as a possible cause for the development of hemorrhoids. However, there are no evidence-based studies on this. (As of March 2012)

Pathogenesis

The sphincter muscles play an essential role in the development of symptomatic hemorrhoids. For example, muscular incontinent patients never have hemorrhoids, while they are quite common in patients with paraplegia . The elastic fibers and collagen fibers that hold the corpus cavernosum recti together with the canalis ani muscle in the rectum above the dentate line or give it tensile strength begin to fragment from the third decade of life due to physiological aging . These fibers cover the vessels like a stocking . This is why hemorrhoids are very rare before the age of 30. At the beginning of the hemorrhoid disease, at least one, usually all three, hemorrhoidal nodules, which then protrude further into the anal canal, enlarge. The reason for this is the degeneration of the fibers in the extracellular matrix of the hemorrhoidal plexus and the increased pressure in the arteriovenous vessels. Injuries to the sensitive mucosal surfaces lead to the well-known symptom of arterial bleeding. Histologically one can see overgrown muscle fibers of the musculus canalis ani and the connective tissue. Using transperineal (through the perineum ) Doppler sonography , increased local blood flow to the hemorrhoidal plexus can be measured. The progression of the displacement of the hemorrhoidal plexus is accelerated by the passage of hard stool, which exerts shear forces on the pads outward. Increased pressure during bowel movements causes a reduced venous flow (blood congestion), and the resulting increased blood pressure in the hemorrhoidal cushion leads to its further enlargement. With the erosion of the epithelium of the hemorrhoidal plexus, inflammatory processes and bleeding occur. In addition, excessive new blood vessels are formed in the hemorrhoidal plexus: This process, known as neovascularization , is driven by increased expression of growth factors such as VEGF and EGFR in the epithelium of the mucosa and submucosa of the hemorrhoidal plexus. The further increase in connective tissue and the hypertrophy of the canalis ani muscle lead to palpable, coarse lumps (second-degree hemorrhoids). Edema and fibrosis further damage this muscle so that it can easily tear in its upper (cranial) area. Characterized the hardened nodes below the can dentate in the sensitive anal skin advance (third degree hemorrhoids). Due to the degeneration of the continence organ, the affected segments reduce their ability to close. Mucus from the rectum can unintentionally get onto the anal skin and lead to eczema (anal eczema) and pruritus ani (itching of the anus). In the final stage, the hemorrhoidal plexus consists largely of connective tissue fibers and a few disordered hypertrophic muscle fibers, making the prolapse of the hemorrhoidal nodes, the anal prolapse, irreversible. At this stage the continence organ is so severely impaired by the damage to the angiomuscular occlusion that control over intestinal gases and stool is disturbed. The progressive displacement of the hemorrhoidal plexus in the distal direction is called the sliding anal lining theory according to William Hamish Fearon Thomson and has replaced the previously common assumption that hemorrhoids are varicose veins and have the same pathogenesis.

Symptoms in the four stages

The symptoms and complaints of a haemorrhoidal disease are very uniform from patient to patient, but are uncharacteristic and occur in a similar form in many other diseases in the area of the rectum. The symptoms are mainly repeated anal bleeding and anal oozing, excruciating itching of the perianal skin ( pruritus ani ), stool smear and anal tissue prolapse. Pain , on the other hand, is rather rare. If pain occurs in the area of the anus, it is mainly due to anal fissures , fistulas or abscesses . The symptoms described are also referred to as the haemorrhoidal symptom complex . Hemorrhoidal disorders can limit certain sexual practices. Symptomatic hemorrhoids are described by those affected as extremely annoying. Annoying , unnecessary or superfluous like hemorrhoids are winged words in everyday parlance. According to the results of surveys with the standardized health questionnaire SF-12 (Short Form-12 Health Survey) , however, they have no significant influence on quality of life - regardless of the degree of illness .

The symptoms correlate with the different stages of the disease: The pathological enlargement of the hemorrhoids is divided into four stages according to a classification system by John Cedric Goligher . Intermediate stages between the individual stages are possible.

First degree hemorrhoids:

- The hemorrhoids are not visible from the outside, they can only be shown proctoscopically .

- The nodes protrude only slightly inside the intestinal tube. The knot formation is fully reversible and there is usually no pain.

In stage I hemorrhoidal disease, painless, bright red bleeding is the main symptom . The bleeding can easily be seen in the form of traces of blood on the surface of the chair ( hematochezia ) or especially on the toilet paper . The blood is mostly bright red. Bright red blood can also be caused by an anal fissure . If, on the other hand, the blood is dark red, there is a high probability that the disease is considerably more serious. In such cases, it is strongly recommended that you see a doctor immediately. The bleeding is the main symptom even in later stages of the disease. The bleeding tendency can be subject to strong fluctuations. After phases of sometimes heavy bleeding after each bowel movement, bleeding can be absent for weeks or months, even without intervention. Hemorrhoidal bleeding rarely leads to anemia ( anemia ).

No data are currently (as of 2012) published showing that asymptomatic first-degree hemorrhoids ever become symptomatic. It is therefore possible that hemorrhoids at this stage are 'normal' endoscopic findings and never lead to a hemorrhoidal disease.

Second degree hemorrhoids:

- When pressed into the anal canal, the knots fall forward, but after a short time they pull back by themselves.

- The hemorrhoids are no longer able to regress on their own.

In stage II, the temporary prolapse of the hemorrhoids leads to disturbed fine continence, which causes increased mucus secretion. This secretion leads to moistening and irritation of the perianal skin, which triggers the itching. The reason for this is anal eczema, which is an indirect consequence of the hemorrhoid problem. Another consequence of hemorrhoid disease can be an anal fissure , which can lead to pain, especially at this stage.

Third degree hemorrhoids:

- One or more lumps can spontaneously appear during exertion. After a bowel movement, they no longer withdraw on their own. The reduction (pushing in) is still possible.

- Entrapment ( incarceration ) and bleeding can occur.

Fourth degree hemorrhoids:

- This stage corresponds to an anal prolapse (stepping down).

- Reduction is no longer possible.

In stages III and IV, the permanent prolapse and pinching of the hemorrhoidal tissue can lead to pain or a dull feeling of pressure in the anal canal. There is no correlation between the size of the hemorrhoids and the symptoms associated with them.

In some cases, the abnormally enlarged hemorrhoidal nodules can exert pressure on the rectal wall and thus trigger the rectoanal reflex, which causes a decrease in the tone of the internal anal sphincter . Defecation is then unsuccessful in such cases. Due to the space they require in the anal canal, they can lead to partial obstruction and hinder the complete evacuation of stool in the rectum. This then often leads to stool smearing (soiling) . Severe, localizable pain is very rare in hemorrhoidal disorders and usually occurs only in stage IV when there is thrombosis in the hemorrhoidal pad.

Taboo

Most patients do not see a doctor about their hemorrhoid condition until the pain outweighs the feeling of shame. The anus is one of the last taboo areas in the body. Hemorrhoids are largely taboo , which is also made clear by the older paraphrases such as "suffering of the secret places" or "embarrassing illness". This taboo is incomprehensible precisely because of the very high degree of widespread suffering. Even in the 21st century, hemorrhoids are not a socially acceptable disease. A taboo and a feeling of shame still mean that many patients seek medical treatment very late, with the disease progressing well. From a rational point of view, there is no reason to do so. The examination techniques for rectal diseases are now very patient-friendly, and some of the symptoms of the - comparatively - harmless haemorrhoidal disease are also present in considerably more serious, life-threatening diseases of the rectum.

Feelings of shame and taboos repeatedly lead to obscure and sometimes fatal forms of self-treatment. Foreign bodies introduced for “treatment” can inadvertently remain in the rectum and become clinically relevant as foreign bodies in the anus and rectum .

diagnosis

examination

After the patient's medical history and description of the symptoms, a visual inspection of the perineum usually takes place first during the initial medical examination . Prevented (prolapsed) fourth-degree hemorrhoids can be easily detected. During the examination, the patient can be encouraged to squeeze the sphincter apparatus, as this is the best way to detect prolapsing second and third degree hemorrhoids. First-degree hemorrhoids can only be diagnosed with a proctoscope . A palpation (palpation) is not suitable. In most cases, further examinations are not necessary to diagnose a hemorrhoidal disease. A rectoscopy can be performed to rule out other proctological diseases and a colonoscopy if a tumor is suspected.

For the planning of surgical interventions for third and fourth degree hemorrhoids, further anorectal examinations such as endoanal ultrasound ( sonography ) can be used. Likewise, if the symptoms cannot be assigned to a hemorrhoidal disease (differential diagnosis).

The (self) diagnosis “hemorrhoids” is often made too frivolously and without the necessary care, due to the extremely high frequency of the disease. There is a risk that significantly more serious illnesses - with similar symptoms - will only be correctly diagnosed with considerable delay. This loss of time can have lethal consequences under certain circumstances.

When diagnosing a haemorrhoidal disease, the most important aspect is the exclusion of other, much more serious and sometimes life-threatening diseases. Only a doctor can safely distinguish hemorrhoids from colon cancer .

Differential diagnosis

Perianal thrombosis

Perianal thromboses, also known as “false hemorrhoids”, are most often confused with hemorrhoids. They have their origin in the perianal subcutaneous venous plexus ( plexus haemorrhoidalis externus ).

Pruritus ani

Anal itching ( pruritus ani ) is a symptom and the result of various causes. It is not an independent clinical picture.

Possible causes of anal itching:

| morphologically conditioned | functionally conditioned | external causes | other causes |

| Anal fissure | Incontinence | allergic contact eczema | Worm disease |

| Anal fistula | Anal prolapse | airtight underwear | radiotherapy |

| Condylomas | hemorrhoids | Excessive hygiene can increase susceptibility to infection | |

| hypertrophic anal papilla | massive diarrhea |

Anal eczema

Anal eczema is the most common cause of anal itching. These are inflammatory processes of the keratinized epithelium of the perianal region. The skin changes include erosions and rhagades . Anal eczema is usually the result of another disease and in about 80% of cases, hemorrhoids are the cause of this skin disorder. The inadequate fine sealing leads to oozing, which results in eczematous changes in the perianal skin. Also anal fistulas can cause oozing in the Pospalte and so lead to an irritative-toxic anal eczema. Another possible cause can be poor anal hygiene. Allergic anal eczema is a special form of allergic contact eczema . They can be caused, for example, by scented toilet paper, certain wet wipes and soaps, but also by some ingredients in hemorrhoid ointments. If there is a lot of anal hair , often in connection with profuse perspiration, anal eczema can also develop acutely and primarily.

Mariske

Skin tags are painless and soft to rough Hautläppchen, which individually or in combination in the area of the vent may occur. They are often the remnants of a perianal thrombosis, but they can also form for no apparent cause. Skin tags do not fill with blood even when pressed and can not be pushed back into the anal canal with digital palpation . They are not classified as a disease.

Anal fibroma

Anal fibromas , also called anal papillae or "cat's teeth" because of their appearance, are wart-like, pedunculated and benign fibromas that arise on the dentate line . They can reach lengths of up to 40 mm ( Fibroma pendulans ).

Anal fissure

Like hemorrhoids, anal fissures can bleed bright red when defecated. They can cause severe pain when defecating. This is an essential difference to hemorrhoids and the main symptom of an anal fissure.

Anal abscess and anal fistula

Anal fistulas are usually caused by anal abscesses (periproctitis) in the area of the crypts within the rectum. It is an inflammation of certain glands that secrete mucus. The anal abscess is the acute and the anal fistula the chronic form of inflammation. Affected patients suffer from intense dull pain when defecating and sitting.

Rectal prolapse

A rectal prolapse is a prolapse of the rectum in which all layers of the rectum penetrate into the rectal clearing and out through the anus. Rectal prolapse is usually caused by weak muscles in the pelvic floor , constipation or diarrhea. While in anal prolapse (4th degree hemorrhoids) the mucous membrane folds are arranged radially and in the shape of a cloverleaf, they are circular in rectal prolapse.

Cancers of the rectum and anus

Endoscopic image of a stenosis caused by rectal cancer

When diagnosing hemorrhoids, in addition to the benign diseases of the continence organ listed above , cancer diseases must also be ruled out by means of differential diagnosis. The main haemorrhoidal symptom blood in the stool also shows malignant diseases (cancer) such as colorectal carcinoma . Anal bleeding is therefore a serious symptom per se that should be clarified promptly and precisely by a suitable doctor. The different color of the blood - hemorrhoidal blood is almost always light red, while tumorous blood is usually dark red to black when it comes from the upper areas of the digestive tract - is by no means sufficient for the differential diagnosis.

Anal canal carcinoma and anal rim carcinoma represent about 1 to 2% of all cancers of the colon. They are particularly often misdiagnosed and, above all, easily mistaken for hemorrhoids due to their mass and appearance. They too have the main symptom of blood in their stool . In addition, pain during bowel movements and itching in the anal area can occur.

Anorectal melanoma is even rarer and accounts for only 0.1% of all anal tumors and 1% of all malignant melanomas . The symptoms, blood in the stool, anal discomfort or pain, are usually diagnosed and treated as hemorrhoids. It takes an average of five months from the first symptoms to the correct diagnosis, so that in many patients a metastasis has already taken place, which significantly worsens the prognosis .

In previous studies, there was evidence that patients with hemorrhoidal disease are at increased risk for anal squamous cell carcinoma, a specific type of anal cancer. Recent studies cannot confirm this connection.

treatment

Treatment is only necessary in the event of a hemorrhoidal disease and not in the presence of hemorrhoids. There are a number of different options for treating hemorrhoidal disease. Which treatment option is ultimately chosen depends primarily on the degree of the disease and the therapy goal - cure or relief. In addition to the general condition of the patient, the number of hemorrhoidal nodes that have occurred and the individual anatomy can also influence the type of treatment. There is no universal treatment method. Usually, minor outpatient procedures are sufficient for first and second degree hemorrhoids . With hemorrhoids from the 3rd degree onwards, usually only a surgical intervention can remedy the situation.

The treatment itself can in principle be carried out by general practitioners (family doctor), surgeons, dermatologists (dermatologist), gynecologists , urologists or proctologists . Proctologists specialize in treating diseases of the rectum. They are therefore usually very familiar with the diagnosis - especially the differential diagnosis - and the treatment of hemorrhoids. The treatment costs are fully reimbursed by the statutory health insurance .

Basic therapy

Basic medical therapy usually precedes conservative, semi-operative or operative measures. Its main purpose is to prevent or at least delay the progression of the haemorrhoid disease. It essentially consists of nutritional advice, which provides for food that is as rich in fiber as possible to increase the volume of stool and a fluid intake of at least two liters per day. The aim of the basic therapy is to have stools that are as soft as possible and to empty the bowels quickly without long pressing. Constipation promotes the formation of hemorrhoids and the progression of the hemorrhoidal disease. The therapeutic benefit of these measures has been confirmed in several prospective studies . Skin irritations can be alleviated through hygiene measures; this includes, for example, cleaning the anus with clear water. Sports activities increase the motility of the intestines. If you are overweight , weight reduction can also alleviate the symptoms of hemorrhoidal disease. The measures of basic therapy described can in principle also be used purely prophylactically .

Hemorrhoidals (hemorrhoid remedies)

Hemorrhoidals are drugs that are used exclusively to treat hemorrhoidal disorders, their symptoms and their sequelae. The drug treatment of a haemorrhoidal disease is symptomatic at best and in no way curative (healing). It may be indicated as an adjuvant to relieve or eliminate the itching, pain and other consequences of the inflammatory reaction . So far, there is no evidence that hemorrhoidals can influence the severity and progression of the disease.

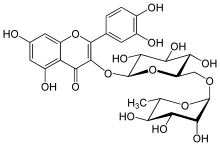

Pharmaceuticals for internal use ( internals ) are offered in pharmacies on the basis of natural substances or natural substance extracts . These include flavonoids such as diosmin or rutin . The drugs mentioned were designed primarily as venous drugs . Since hemorrhoids are arterially supplied vascular cushions and not venous vascular clusters, there is no reasonable justification for the use for the treatment of these drugs according to the guidelines of the German Dermatological Society (DDG) and the German Society for Coloproctology (DGK) Hemorrhoid disease. In Germany, these drugs are of almost no importance. In a randomized double- blind study with flavonoids, which also include rutin, significant positive effects in terms of bleeding arrest and reduced recurrence rate were found, but no cure is possible with this treatment option. The primary goal of drug therapy is to suppress bleeding in order to plan a curative therapy such as sclerotherapy, rubber band ligation or surgery at a convenient time.

There is a large number of ointments, creams and suppositories ("suppositories") available for local therapy . The latter are also available with a gauze insert as anal tampons . The majority of the hemorrhoidal drugs on offer are available without a prescription .

There are no controlled clinical studies for any of the hemorrhoidals on the market that prove the effectiveness of these drugs in hemorrhoidal disorders. This also applies to the ointments or suppositories with local anesthetics , astringents or anti-inflammatory agents classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as indispensable drugs for the short-term symptomatic treatment of hemorrhoids . The WHO recommends mild astringents such as basic bismuth gallate , zinc oxide or witch hazel extract ( Hamamelidis cortex ) as " calming creams " to relieve symptoms, which are applied locally as ointments or suppositories together with lubricants , vasoconstrictors or mild antiseptics . Local anesthetics in these formulations can relieve pain. According to the WHO, corticosteroids can be used briefly in combination with the formulations mentioned if there is no local infection . Prolonged use of corticosteroids should be avoided, as this can lead to atrophy of the anoderm (breakdown of the anal skin).

Outpatient measures

In the case of hemorrhoids of the first and second degree, attempts are made to avoid an operation or at least postpone it for a few years by carrying out minor outpatient interventions. The following treatment methods are essentially used:

- Sclerotherapy of hemorrhoids : Smaller hemorrhoidal nodules are held in place with a tubular device ( proctoscope ) and a sclerosing liquid, for example phenol dissolved in almond oil , 5% quinine solution or polidocanol , is injected. The inflammatory reaction caused by this is intended to locally reduce the blood flow through subsequent scarring, shrink the hemorrhoids and fix the hemorrhoidal nodes on the surface. The very simple and inexpensive procedure is usually carried out in several partial treatments at intervals of around four to six weeks and is usually completely painless. There is little risk of necrosis . Necrosis mainly occurs when the injection technique is poor. The probability of a recurrence is high (high recurrence rate ). Sclerotherapy is the treatment of choice for symptomatic grade 1 hemorrhoids.

- Rubber band ligation (also called Barron's rubber ligation ) : The knot is clamped off by a rubber band slipped over it ( ligature ) and falls off in the following days. This is the most popular treatment for second-degree hemorrhoids. The recurrence rate is lower than with sclerotherapy. Risks of the mostly harmless treatment exist when taking "blood-thinning" drugs (secondary bleeding) and with latex allergies (rarely serious, allergic reactions) as well as with chronic inflammatory bowel diseases (fistula formation) and HIV infection (infections). For the treatment of symptomatic second-degree hemorrhoids, rubber band ligation is the method of choice.

Both procedures are performed through a proctoscope, which gives the treating physician access to the hemorrhoids. Neither anesthesia nor sedation is necessary.

The Infrarotkoagulation is rarely used for hemorrhoids first and second degree. The Kryohämorrhoidektomie (freezing) and the maximum anal sphincter dilatation after Lord are now no longer used, and their use is clearly discouraged.

Surgical procedure

For the treatment of hemorrhoids, surgery is usually only performed if the conservative measures have failed or the degree of the disease does not suggest that successful conservative treatment can be expected. The aim of all currently common interventions is to restore normal anatomical conditions. In no case is the goal to completely remove the enlarged hemorrhoidal cushions, as these are essential for fine continence. Surgical intervention is necessary in around 10% of patients who see a doctor with a hemorrhoidal disease.

Classic procedures

In the case of a far advanced haemorrhoid disease, which is mainly characterized by a prolapse of the haemorrhoidal tissue that can no longer be reduced (haemorrhoids 4th degree), an operation is necessary to achieve healing. This procedure is called a hemorrhoidectomy . There are several hemorrhoidectomy techniques, which are differentiated and named after their inventors. All procedures are performed under anesthesia or spinal anesthesia (e.g. saddle block) and usually require a hospital stay of several days (inpatient). The healing takes several weeks and is usually painful. In the acute stage (that is, the hemorrhoids are either thrombosed or pinched), conservative treatment is initially given before surgery.

Depending on whether the hemorrhoidal disease is segmental or circular (all hemorrhoidal cushions prolapse), either segmental or circular procedures are used. The segmental procedures include, for example, the Milligan-Morgan open hemorrhoidectomy , the Parks submucosal hemorrhoidectomy, and the Ferguson closed hemorrhoidectomy . In contrast, the reconstructive hemorrhoidectomy according to Fansler-Arnold and the supraanodermal hemorrhoidectomy according to Whitehead are counted among the circular procedures. Other authors divide the various procedures into open and closed hemorrhoidectomies. The open procedures include, for example, the Milligan-Morgan operation (also known as the three-lobe method), while the closed procedures include the Parks , Ferguson and Fansler-Arnold techniques. The Fansler-Arnold method is mainly used for the reconstruction of the anal canal, as it is occasionally required for 4th degree hemorrhoids that are fixed to the outside. Laser-assisted hemorrhoidectomy procedures offer no advantages over conventional surgical procedures.

Until the 1980s, complete removal (“eradicating” the hemorrhoidal cushions) was the goal of surgical interventions in advanced hemorrhoidal diseases. An undesirable consequence of these treatments was fecal incontinence. The supra-anodermal hemorrhoidectomy (Whitehead operation ) described for the first time in 1882 by the British Walter Whitehead (1840-1913) is now considered a " malpractice " due to significant postoperative complications .

Modern procedures

The stapled hemorrhoidopexy by Longo is a less painful closed process, in which by using a specific operation unit, the stacker, the anal skin is lifted. In contrast to hemorrhoidectomy, hemorrhoidopexy does not involve resection of the hemorrhoidal cushion, but a circular resection of the mucosal cuff ( mucosectomy ), about 30 mm above the corpus cavernosum recti . The subsequent scarring and secondary remodeling processes reduce the hemorrhoidal cushions to a normal size and return them to their original position. Since the procedure does not take place in the area of the extremely sensitive anoderm, the method is largely painless and - compared to a hemorrhoidectomy - very comfortable for the patient. This technique is now widely used and the method of choice for the treatment of third-degree circular hemorrhoids. However, the staple method is not suitable for fourth-degree hemorrhoids, as a prolapse usually occurs again after the operation.

The Doppler-controlled hemorrhoidal artery ligation according to Morinaga (HAL) is a minimally invasive procedure developed in 1995 for hemorrhoids of the second and early third degree, in which no tissue is removed, but only the arteries supplying the hemorrhoids are tied off. The vessels are specifically searched for with a special ultrasound probe , a Doppler proctoscope. After the supply arteries are tied, the hemorrhoidal nodes gradually begin to shrink. The recurrence rate is comparatively high; however, the treatment can easily be repeated. So far, there has only been one randomized controlled study with a relatively small number of patients (60 in total), which is why the method has not yet been evaluated by the guidelines. A further development of the HAL method is the transanal haemorrhoidal artery ligation (THD), in which additional suture loops are used to reposition ("lift") the protruding anal mucosa. This procedure is also intended to treat second and third degree hemorrhoids. The results are comparable to Longo's stapled hemorrhoidopexy. So far it has only been used sporadically.

The minimally invasive, subanodermal submucosal hemorrhoidoplasty (MISSH) was developed in 1996 by the surgeon Gunther Matthias Burgard from Kaiserslautern and has been used since then by himself, but now also by a number of other specialists at home and abroad. The technique is also suitable for fixed fourth-degree prolapse forms and - in contrast to circular procedures (such as Longo) - offers the option of operating on individual nodes. The corresponding supply artery is constricted, the knot is mobilized, excess hemorrhoidal plexus is removed with a shaver and the skin is gathered in a painless area by means of anal lifting.

At the beginning of the 21st century, the LigaSure procedure of hemorrhoidectomy was developed. It is also suitable for the treatment of advanced fourth degree hemorrhoid disease. The methods of HF surgery (coagulation and blood-free closure of the vessels) are used. Compared to the established procedures, a reduction in pain, a lower tendency to bleed during and after the procedure, shorter operation times and an earlier ability to work were found in several studies. No data are yet available on long-term experience and relapse rates. Disadvantages for the attending physician are the high investments in an HF generator of around € 19,000 (, 2011) and in HF pliers that can often only be used once.

Risks and Complications of Surgical Treatment

After the operation, bleeding and pain are common, especially with traditional procedures. Depending on the treatment method and the findings, working patients are usually on sick leave for one to three weeks . Defecation control may be impaired for the first few days. This problem is usually temporary and gets better over time. In rare cases, scar tissue narrows the anus, which can make it difficult to pass stool. This tightness of the sphincter muscles ( anal stenosis ) can be temporary or persistent.

Acute urinary retention is the most common complication after hemorrhoid surgery , with a frequency of around 20 percent . It occurs mainly in elderly patients and is also observed when rubber band ligatures are placed. An important risk factor is obviously the type of anesthesia, with spinal anesthesia significantly increasing the risk. With the modern surgical procedures stapled hemorrhoidopexy and LigaSure, the risk of acute urinary retention is significantly lower. By restricting the fluid intake during the operation and using adequate pain management after the operation, urinary retention can largely be avoided.

After sclerotherapy or rubber band ligation, bacteremia , which is the temporary presence of bacteria in the blood, can be detected in around 8% of patients . A preventive administration of antibiotics ( perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is carried out) - even with the surgical procedure for the treatment of hemorrhoids - usually only in high-risk patients to a endocarditis prevention ( endocarditis ).

In around 2.5% of Longo hemorrhoid operations, a rectal diverticulum ( rectal pocket syndrome ), a usually one-sided protrusion of the rectal mucosa after a tear in the rectal muscles, can form as a complication.

A very rare, but by far the most dangerous complication is Fournier gangrene . This necrotizing perineal sepsis can occur and be fatal in all procedures for the treatment of a hemorrhoidal disease, from sclerotherapy to rubber band ligation and staple hemorrhoidopexy to hemorrhoidectomy.

In principle, enlarged hemorrhoids can develop again later (relapse).

Treatment costs and reimbursement

Hemorrhoid operations are remunerated according to G26Z (Other interventions on the anus) of the DRG system . A mean inpatient stay of 3.8 days per patient is calculated. It is a mixed calculation of several different surgical procedures. In 2009, the base case value was € 2,600 and the valuation ratio was 0.53. The product of both factors results in an amount of € 1378, which the statutory health insurance companies have to pay to the treating hospital after the hemorrhoid operation. If the operation is carried out on an outpatient basis, the EBM fee in 2009 was € 472.01, which the health insurers have to reimburse. The mixed calculation means that due to the significantly higher material costs (including consumables, depreciation of equipment investments ) of modern methods such as forklifts, the costs can only be compensated by reducing the length of time patients stay in the clinic. In principle, this fits in with modern procedures that offer faster convalescence . However, if you are discharged on the first day after the operation, the minimum length of stay will be one day below, which will result in a discount of 44% on the DRG amount. The remaining approx. 800 € are often not enough to cover material costs. Some authors therefore express the fear that hospitals have no interest in discharging patients before the lower limit of length of stay has been reached.

Veterinary medicine

Hemorrhoids play a minor role in veterinary practice. For the development of new surgical techniques, model organisms are selected that come as close as possible to humans in terms of their size and anatomy. In particular, domestic pigs and primates , such as the hooded capuchin ( Cebus apella ), are used as animal models. The hemorrhoids can be created by ligating the draining veins of the hemorrhoidal plexus.

Medical history

Hemorrhoid disease is not a modern disease. Doctors have been dealing with its diagnosis and therapy for thousands of years. Egyptian pharaohs had, among other things, a 'guardian of the anus' in their medical staff, whose tasks included the treatment of hemorrhoidal diseases. Hemorrhoidal diseases are first described in the Ebers Papyrus (approx. 1500 BC). In the Old Testament they are mentioned in 1 Samuel chapter 5. Hippocrates of Kos recommended treatment with a branding iron, an extremely painful therapy method in which the hemorrhoids were forcibly pulled outwards and burned away with a red-hot iron. He also described a suppository (suppository) used to treat hemorrhoids.

“If you want to treat with suppositories, you take the back shell of a squid, a third of lead root, asphalt, alum, a little (copper) blossom, gall apple, verdigris, pour boiled honey over it, make a fairly long cone and place it like that until the hemorrhoids have disappeared. "

Hippocrates also mentions procedures corresponding to sclerotherapy, Barron's ligation, and hemorrhoidal excision. The 'incandescent branding iron' was still recommended in the 19th century to stop bleeding after the operation of “external” and “internal hemorrhoids”. It was shaped like a bean. In 1855, Professor Reinhold Köhler (1826–1873) from Tübingen described the burning out of hemorrhoids as follows:

"You give an enema, which is to be emptied again immediately to drive the hemorrhoidal nodes in front of the anus. The patient is then positioned as in the operation of the anal fistula, the knot is grasped and a needle with a double thread is passed through it; two assistants hold the knots outside the sphincter by means of the thread ends. Immediately a rod-shaped, incandescent iron is inserted 3 to 4 centimeters deep into the anus and left until it has turned black; when the iron penetrates, the knots are let back a little. This kind of etching is repeated twice; Finally the skin of the anus, which contributes to the formation of the sacs, is destroyed by pressing a conical branding iron, truncated at the tip, onto the anus. The consequences of the operation are severe pain, urinary problems, feverish movements, sometimes even delirium; in Boyer's cases, these after-effects disappeared after a few days. "

The Greek doctor Paulos von Aigina , who lived in the 7th century, describes the surgical treatment of hemorrhoids in his medical collections . Before the procedure, he recommends the repeated use of enemas to empty the intestines. He also described the ligature of hemorrhoidal knots with thread. The Englishman Johannes von Arderne (1307-1392) is considered the first proctologist. He studied the hemorrhoids extensively. The bleeding was a symptom for him, against which he used hemostatic agents. He wrote of "veins". Apparently he did not perform any surgical interventions. At the beginning of the 19th century, Frederick Salmon (1796–1868) developed a surgical procedure in which he cut the hemorrhoid segments down to the stalk in the insensitive rectal mucosa and placed a ligature at this point . His method has been praised as being 'painless'.

The designation golden veins lasted until the 20th century. The reason for this was that, according to Galenus, the bleeding, similar to bloodletting, was considered useful so that the 'bad juices' could drain off. In 1919, William Ernest Miles (1869–1947) was the first to recognize the three arterial blood vessels that supply the hemorrhoidal plexus, but continued to speak of “veins”. The German surgeon Friedrich Stelzner recognized at the beginning of the 1960s that the corpus cavernosum recti is the morphological basis of hemorrhoids and that the assumption that hemorrhoids are veins is an error that has existed for millennia. From today's perspective it is still incomprehensible that this error could last so long. Doctors and patients always saw bright red, that is, arterial blood during operations and bleeding of the hemorrhoids.

Other names for hemorrhoids or piles were gold varices also genital warts and Feigblattern and Feig (from the Latin ficus ).

The method of obliteration was developed relatively late. The first recorded report of hemorrhoid obliteration dates back to 1869. It was carried out by Morgan at St. Mercer's Hospital in Dublin with ferric sulfate . This sclerosing method was originally developed in the United States in 1836 for the treatment of nevi . Around 1871, Mitchell in Clinto ( Illinois ) injected phenol for the first time to obliterate hemorrhoids. He used a mixture of one part phenol with two parts olive oil. Mitchell tried to keep the process a secret, but the process spread quickly and was used by many quacks , who sometimes significantly changed the original recipe. Five years later, a Chicago university professor became aware of the procedure and identified 3,300 cases of hemorrhoid obliteration with phenol. Later on, olive oil was often replaced by castor oil .

Curiosities

In the historical literature, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Napoleon Bonaparte discussed a possible disease from hemorrhoids : Napoleon is said to have suffered from hemorrhoids from 1814 onwards. It is believed that he was plagued by very painful, thrombosed hemorrhoids on June 18, 1815, the day of the Battle of Waterloo . The pain is said to have been so great that day that the French Emperor could only sit on a chair with the hay underneath. There are historians and serious writers who suggest that this is why Napoleon lost this last great battle. Because of the pain he suffered from sleep deprivation, and the use of opium drops to relieve pain had a negative impact on his skills as a general . Napoleon could hardly keep himself on his horse.

Occasionally the “insider tip” is spread in tabloids or internet forums that “hemorrhoid cream” is helpful against facial wrinkles or swelling of the eyelids. In fact, most hemorrhoid creams are completely unsuitable or even harmful for this purpose due to the local anesthetics they contain, such as lidocaine or anti-inflammatory agents such as cortisone . The desired effect can only be expected from an ointment with an astringent ( astringent ) active ingredient. Ointments with witch hazel extract, a vegetable tanning agent, are largely harmless . Hamamelis ointments are not only offered as hemorrhoid creams, but also in cosmetically more suitable, less fatty preparations.

For devout Catholics, St. Fiacrius is the patron saint against hemorrhoids. According to legend, a stone on which the hermit sat in the 7th century is said to have "freed their hemorrhoids" from many believers later.

In 2004, the heirs of the American singer and songwriter Johnny Cash forbade the use of the most successful Cash song, the Ring of Fire, to advertise a hemorrhoidal ointment. The planned use of the line “And it burns, burns, burns, the ring of fire, the ring of fire” for advertising was viewed by the Cash heirs as a disparagement of the song. Ring of Fire deals with the "transformative power of love". The song was composed in 1962 by Merle Kilgore and Cash's later wife June Carter . Kilgore said in an interview that he himself often joked about hemorrhoids when the song was played on stage.

literature

Reference books

- Volker Wienert , Horst Mlitz, Franz Raulf: Handbook of hemorrhoidal diseases . Uni-Med, Bremen a. a. 2008, ISBN 978-3-8374-1006-8 .

- Friedrich Anton Weiser: Hemorrhoids: let's talk about it. 1st edition. Verlag-Haus der Ärzte, Vienna 2006, ISBN 3-901488-80-4 .

- Volker Dinnendahl: Hemorrhoid remedies. In: Ulrich Schwabe, Dieter Paffrath: Drug Ordinance Report 2003. [Electronic resource]: Current data, costs, trends and comments. Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 978-3-642-18512-0 , pp. 506-512. limited preview in Google Book search.

- Freya Reinhard, Jens J. Kirsch: Hemorrhoids and the diseased rectum. A guide. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-017587-4 .

- Ernst Stein: Proctology: Textbook and Atlas. 4th edition, Springer, 2002, ISBN 3-540-43033-4 .

- Peter Grunert: Hemorrhoids - the pain that is often hidden. Ways of healing. Goldmann, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-442-14161-3 .

Technical article

- Caroline Sanchez, Bertram T. Chinn: Hemorrhoids. In: Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. Volume 24, number 1, March 2011, pp. 5-13, doi: 10.1055 / s-0031-1272818 , PMID 22379400 , PMC 3140328 (free full text).

- Erica B. Sneider, Justin A. Maykel: Diagnosis and management of symptomatic hemorrhoids. In: Surgical Clinics of North America . Volume 90, Number 1, February 2010, pp. 17-32, Table of Contents, doi: 10.1016 / j.suc.2009.10.005 , PMID 20109630 (review).

- Alexander Herold: Proctology: Hemorrhoidal disease, fissure, abscess, fistula. (PDF; 325 kB) In: The gastroenterologist. Volume 4, Number 2, March 2009, pp. 137-146, doi: 10.1007 / s11377-009-0281-7 .

- Hans Georg Kuehn, Ole Gebbensleben a. a .: Relationship between anal symptoms and anal findings. In: International journal of medical sciences. Volume 6, Number 2, 2009, pp. 77-84, PMID 19277253 . PMC 2653786 (free full text).

- Pierre Plancherel: The hemorrhoid disease. In: Alexander Neiger (Ed.): Diseases of the anus and the rectum. Basel 1973 (= gastroenterological advanced training courses for practice , 3), pp. 36–45.

- Shauna Lorenzo-Rivero: Hemorrhoids: Diagnosis and Current Management. In: The American surgeon. Volume 75, Number 8, August 2009, pp. 635-642, PMID 19725283 (review).

- Gordon V. Ohning, Gustavo A. Machicado, Dennis M. Jensen: Definitive therapy for internal hemorrhoids - new opportunities and options. In: Reviews in gastroenterological disorders. Volume 9, Number 1, 2009, pp. 16-26, PMID 19367214 (review).

- Manish Chand, Natalie Dabbas, Guy F. Nash: The management of haemorrhoids. In: British journal of hospital medicine. Volume 69, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 35-40, PMID 18293730 (review).

- Joy N. Hussain: Hemorrhoids. In: Primary care. Volume 26, Number 1, March 1999, pp. 35-51, PMID 9922293 (review).

- Peter B. Loder, Michael A. Kamm u. a .: Haemorrhoids: pathology, pathophysiology and aetiology. In: British Journal of Surgery . Volume 81, Number 7, July 1994, pp. 946-954, PMID 7922085 (review).

- Robert Wohlwend, R. Amgwerd: The surgical treatment of the hemorrhoidal disease and its consequences. In: Alexander Neiger (Ed.): Diseases of the anus and the rectum. Basel 1973 (= gastroenterological advanced training courses for practice , 3), pp. 46–53.

Web links

- AK Joos: S3 guidelines for hemorrhoidal disorders (PDF) guidelines of the German Society for Coloproctology, 04/2019, AWMF register number 081/007; accessed on November 12, 2017

- A. Furtwängler: Hemorrhoids. at the professional association of German surgeons

- DermIS.net: hemorrhoids. Dermatology Information Service in cooperation with the Department of Clinical Social Medicine (Heidelberg University) and the Erlangen Dermatology Clinic (Erlangen-Nuremberg University)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c R. Hesterberg: Proctology for the urologist. In: Der Urologe B. Volume 40, number 2, 2000, pp. 168-176, doi: 10.1007 / s001310050357 .

- ↑ a b c J. Lange, B. Mölle, J. Girona (eds.): Surgical proctology. Springer, 2005, ISBN 3-540-20030-4 , p. 17. Restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l G. Pühse, F. Raulf: Das Hämorrhoidalleiden. In: Urologe A. Volume 46, number 3, March 2007, pp. W303-W314, doi: 10.1007 / s00120-006-1281-6 . PMID 17294153 . (Review).

- ↑ a b c d e F. Raulf: Functional anatomy of the anorectum. In: The dermatologist. Volume 55, Number 3, March 2004, pp. 233-239, doi: 10.1007 / s00105-004-0689-4 . PMID 15029428 .

- ↑ a b c d e f F. Stelzner , J. Staubesand, H. Machleidt: The corpus cavernosum recti - the basis of the internal hemorrhoids. In: Langenbecks Arch Klin Chir Ver Dtsch Z Chir. Volume 299, 1962, pp. 302-312, PMID 13916799 .

- ↑ a b c WH Thomson: The nature of haemorrhoids. In: The British Journal of Surgery . Volume 62, Number 7, July 1975, pp. 542-552, PMID 1174785 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h H.-P. Bruch, UJ Roblick: Pathophysiology of the hemorrhoid disease. In: The surgeon . Volume 72, number 6, 2001, pp. 656-659, doi: 10.1007 / s001040170120 . PMID 11469085 . (Review).

- ^ CP Gibbons, EA Trowbridge et al. a .: Role of anal cushions in maintaining continence. In: The Lancet . Volume 1, Number 8486, April 1986, pp. 886-888, PMID 2870357 .

- ↑ H. Stieve : About the importance of venous miracle nets for the closure of individual openings in the human body. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 54, Number 3, 1928, pp. 87-90, doi: 10.1055 / s-0028-1124946

- ↑ a b HH Hansen: The importance of the canalis ani muscle for continence and anorectal diseases. In: Langenbecks Arch Chir. Volume 341, Number 1, June 1976, pp. 23-37, PMID 957838 .

- ↑ D. Schößler: Anal atresia - functional results and psychosocial stress. (PDF; 1.2 MB) Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau, 2008, pp. 10–11.

- ^ W. Lierse: Anatomical foundations of continence. In: E. Farthmann, L. Fiedler (Ed.): The anal continence and its restoration. Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1984, ISBN 3-541-12001-0 , pp. 7-9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o A. Herold, C. Breitkopf u. a .: Hemorrhoidal disease. ( Memento from April 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 749 kB) Guidelines of the German Society for Coloproctology, AWMF , as of July 2008

- ↑ M. Schünke, E. Schulte u. a .: Prometheus Learning Atlas of Anatomy. Georg Thieme, 2009, ISBN 3-13-139532-X , p. 236. Restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ G. Brisinda: How to treat haemorrhoids. Prevention is best; haemorrhoidectomy needs skilled operators. In: BMJ. Volume 321, Number 7261, September 2000, pp. 582-583, PMID 10977817 . PMC 1118483 (free full text).

- ↑ HH Hansen: New aspects on the pathogenesis and therapy of hemorrhoidal disease. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 102, Number 35, September 1977, pp. 1244-1248, doi: 10.1055 / s-0028-1105487 . PMID 902585 .

- ↑ a b H. Rohde: What are hemorrhoids? Collective term, symptom or illness? In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . Volume 102, Number 4, 2005, pp. A-209 / B-172 / C-165.

- ↑ H. Rohde: Teaching Atlas of proctology. Georg Thieme, 2006, ISBN 3-13-140881-2 , p. 100. Limited preview in Google book search

- ↑ a b JJ Kirsch: What are hemorrhoids? Confusing claims. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt . Volume 102, Number 27, 2005, pp. A-1969 / B-1664 / C-1568.

- ↑ a b c d JJ Kirsch, BD Grimm: The conservative treatment of hemorrhoids. (PDF; 1.2 MB) In: Wiener Medical Wochenschrift . 154, 2004, pp. 50-55. PMID 15038575 .

- ↑ G. Staude: Proctology. In: Wiener Medical Wochenschrift . Volume 154, Numbers 3-4, 2004, pp. 43-44, PMID 15038573 .

- ↑ HS Füeßl: Internal medicine in questions and answers. Georg Thieme, 2004, ISBN 3-13-496308-6 , p. 63. Restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ a b c O. Kaidar-Person, B. Person, SD Wexner: Hemorrhoidal disease: A comprehensive review. In: J Am Coll Surg. Volume 204, number 1, January 2007, pp. 102-117, doi: 10.1016 / j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.022 . PMID 17189119 . (Review).

- ↑ SW Hosking, HL Smart u. a .: Anorectal varices, haemorrhoids, and portal hypertension. In: The Lancet . Volume 1, Number 8634, February 1989, pp. 349-352, PMID 2563507 .

- ^ German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information: Diseases of the veins, lymph vessels and lymph nodes, not elsewhere classified (I80-I89). ( Memento of February 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Retrieved March 1, 2012

- ↑ a b AF Avsar, HL Keskin: Haemorrhoids during pregnancy. In: J Obstet Gynaecol. Volume 30, Number 3, April 2010, pp. 231-237, doi: 10.3109 / 01443610903439242 . PMID 20373920 . (Review).

- ↑ W. Stumpf: Homeopathy. Gräfe and Unzer, 2008, ISBN 3-8338-1144-7 , p. 180. Limited preview in the Google book search Hemorrhoids are enlarged veins or varicose veins at the exit of the rectum, ...

- ↑ I. Scharphuis: The oral medical examination . Urban & Fischer, 2007, ISBN 3-437-55793-9 , p. 107. limited preview in the Google book search Question: What are hemorrhoids? Answer: Hemorrhoids are varicose veins of the haemorrhoidal plexus, a rectal arterio-venous vascular system.

- ↑ JW Rohen: Topographical Anatomy. Schattauer, 2008, ISBN 3-7945-2616-3 , p. 374. Restricted preview in the Google book search

- ↑ HW Baenkler: Internal Medicine. Georg Thieme, 2001, p. 253, ISBN 3-13-128751-9 , p. 1125. limited preview in Google book search

- ↑ a b c d e f g S. Riss, FA Weiser u. a .: The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. In: International Journal of Colorectal Disease . Volume 27, Number 2, 2011, pp. 215-220, doi: 10.1007 / s00384-011-1316-3 . PMID 21932016 .

- ↑ a b c W. Luyken: Hemorrhoids as faithful companions. In: Oberpfalznetz.de of February 24, 2011

- ↑ JJ Kirsch: Proctology Today. In: Coloproctology . Volume 24, 2002, pp. 239-241.

- ↑ P. Otto: The hemorrhoid disease: pathogenesis, diagnostics and conservative therapy. In: Therapy Week. Volume 39, 1989, pp. 1124-1129.

- ↑ V. Wienert, H. Mlitz: Atlas coloproctology. Blackwell Science Publishing, 1997.

- ↑ a b J. Blech: Phantom in the Po . In: Der Spiegel . No. 51 , 2004, p. 172 ( online ).

- ↑ a b c PJ Nisar, JH Scholefield: Managing haemorrhoids. In: BMJ. Volume 327, number 7419, October 2003, pp. 847-851, doi: 10.1136 / bmj.327.7419.847 . PMID 14551102 . PMC 214027 (free full text). (Review).

- ^ H. Rohde, H. Christ: Hemorrhoids are suspected and treated too often: surveys in 548 patients with anal complaints. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 129, 2004, pp. 1965-1969.

- ↑ VW Fazio, JJ Tjandra: The management of perianal diseases. In: Advances in surgery. Volume 29, 1996, pp. 59-78, PMID 8719995 . (Review).

- ↑ a b WP Mazier: Hemorrhoids, fissures, and pruritus ani. In: The Surgical clinics of North America. Volume 74, Number 6, December 1994, pp. 1277-1292, PMID 7985064 . (Review).

- ↑ D. Nagle, RH Rolandelli: Primary care office management of perianal and anal disease. In: Primary care. Volume 23, Number 3, September 1996, pp. 609-620, PMID 8888347 . (Review).

- ^ H. Rohde: Routine anal cleansing, so-called hemorrhoids, and perianal dermatitis: cause and effect? In: Diseases of the Colon and Rectum . Volume 43, Number 4, April 2000, pp. 561-563, PMID 10789760 .

- ^ A b H. Rohde: Diagnostic errors. In: The Lancet . Volume 356, number 9237, October 2000, p. 1278, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (05) 73886-1 . PMID 11072979 .

- ↑ JC Gazet, W. Redding, JW Rickett: The prevalence of haemorrhoids. A preliminary survey. In: Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Volume 63 Suppl, 1970, pp. 78-80, PMID 5525514 . PMC 1811405 (free full text).

- ^ PA Haas, GP Haas et al. a .: The prevalence of hemorrhoids. In: Diseases of the Colon and Rectum . Volume 26, Number 7, July 1983, pp. 435-439, PMID 6861574 .

- ↑ a b c JF Johanson, A. Sonnenberg: The prevalence of hemorrhoids and chronic constipation. An epidemiologic study. In: Gastroenterology. Volume 98, Number 2, February 1990, pp. 380-386, PMID 2295392 .

- ^ H. Rohde, H. Christ: Hemorrhoids are suspected and treated too often: surveys in 548 patients with anal complaints. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 129, Number 38, September 2004, pp. 1965-1969, doi: 10.1055 / s-2004-831833 . PMID 15375737 .

- ↑ T. Tallarita, C. Gurrieri et al. a .: Clinical features of hemorrhoidal disease in renal transplant recipients. In: Transplant Proc. Volume 42, number 4, May 2010, pp. 1171-1173, doi: 10.1016 / j.transproceed.2010.03.070 . PMID 20534253 .

- ↑ M. Hulme-Moir, DC Bartolo: Hemorrhoids. In: Gastroenterol Clin North Am. Volume 30, Number 1, March 2001, pp. 183-197, PMID 11394030 . (Review).

- ↑ DP Burkitt: Varicose veins, deep vein thrombosis, and haemorrhoids: epidemiology and suggested aetiology. In: British medical journal. Volume 2, Number 5813, June 1972, pp. 556-561, PMID 5032782 . PMC 1788140 (free full text).

- ↑ a b S. Riss, FA Weiser u. a .: Haemorrhoids, constipation and faecal incontinence: is there any relationship? In: Colorectal disease. Volume 13, number 8, August 2011, pp. E227 – e233, doi: 10.1111 / j.1463-1318.2011.02632.x . PMID 21689320 .

- ^ NJ Talley: Definitions, epidemiology, and impact of chronic constipation. In: Reviews in gastroenterological disorders. Volume 4 Suppl 2, 2004, pp. S3-S10, PMID 15184814 . (Review).

- ^ DP Burkitt, HC Trowell: Dietary fiber and western diseases. In: Irish medical journal. Volume 70, Number 9, June 1977, pp. 272-277, PMID 893060 .

- ↑ A. Hirner, K. Weise: Surgery: cut for cut. Georg Thieme, 2004, ISBN 3-13-130841-9 , p. 630. Limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ JW Anderson, P. Baird et al. a .: Health benefits of dietary fiber. In: Nutrition reviews. Volume 67, Number 4, April 2009, pp. 188-205, doi: 10.1111 / j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x . PMID 19335713 . (Review).

- ↑ DM Klurfeld: The role of dietary fiber in gastrointestinal disease. In: Journal of the American Dietetic Association. Volume 87, Number 9, September 1987, pp. 1172-1177, PMID 3040840 .

- ↑ KY Tan, F. Seow-Choen: Fiber and colorectal diseases: separating fact from fiction. In: World journal of gastroenterology. Volume 13, Number 31, August 2007, pp. 4161-4167, PMID 17696243 . (Review).

- ↑ F. Pigot, L. Siproudhis, FA Allaert: Risk factors associated with hemorrhoidal symptoms in specialized consultation. (PDF; 103 kB) In: Gastroenterology clinique et biologique. Volume 29, Number 12, December 2005, pp. 1270-1274, PMID 16518286 .

- ↑ C. Hasse: Hemorrhoids in Pregnancy. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 126, Numbers 28-29, July 2001, p. 832, doi: 10.1055 / s-2001-15701 . PMID 11499269 .

- ^ H. Rohde: Differential diagnosis of hemorrhoids in pregnancy. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 126, number 46, November 2001, p. 1302, doi: 10.1055 / s-2001-18474 . PMID 11709734 .

- ↑ A. Staroselsky, AA Nava-Ocampo et al. a .: Hemorrhoids in pregnancy. In: Canadian family physician Médecin de famille canadien. Volume 54, Number 2, February 2008, pp. 189-190, PMID 18272631 . PMC 2278306 (free full text).

- ↑ L. Abramowitz, I. Sobhani et al. a .: Anal fissure and thrombosed external hemorrhoids before and after delivery. In: Diseases of the Colon and Rectum . Volume 45, Number 5, May 2002, pp. 650-655, PMID 12004215 .

- ↑ JF Thompson, CL Roberts et al. a .: Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. In: Birth. Volume 29, Number 2, June 2002, pp. 83-94, PMID 12051189 .

- ↑ JL Grobe, RA Kozarek, RA Sanowski: colonoscopic retroflexion in the evaluation of rectal disease. In: The American Journal of Gastroenterology. Volume 77, Number 11, November 1982, pp. 856-858, PMID 7137139 .

- ↑ Peter Reuter: Springer Lexicon Medicine. Springer, Berlin a. a. 2004, ISBN 3-540-20412-1 , p. 869.

- ↑ F. Stelzner: The hemorrhoids and other diseases of the corpus cavernosum recti and the anal canal. In: German Medical Weekly . Volume 88, April 1963, pp. 689-696, doi: 10.1055 / s-0028-1111996 . PMID 13983815 .

- ^ PA Haas, TA Fox, GP Haas: The pathogenesis of hemorrhoids. In: Diseases of the Colon and Rectum . Volume 27, Number 7, July 1984, pp. 442-450, PMID 6745015 .

- ↑ F. Aigner, G. Bodner u. a .: The vascular nature of hemorrhoids. In: Journal of gastrointestinal surgery. Volume 10, number 7, 2006 Jul-Aug, pp. 1044-1050, doi: 10.1016 / j.gassur.2005.12.004 . PMID 16843876 .

- ↑ F. Aigner, H. Gruber u. a .: Revised morphology and hemodynamics of the anorectal vascular plexus: impact on the course of hemorrhoidal disease. In: International journal of colorectal disease. Volume 24, Number 1, January 2009, pp. 105-113, doi: 10.1007 / s00384-008-0572-3 . PMID 18766355 .