Coronary heart disease

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| I20 - I25 | Ischemic heart disease |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

- Ventricles and atria (white): right ventricle (RV), right atrium (RA) and left ventricle (LV).

The left atrium (LA) is covered by the left ventricle.

- Arteries (red) and veins (blue) of the great and small circulation: aortic arch of the aorta (A), truncus pulmonalis (TP) with left and right pulmonary artery (RPA and LPA) and vena cava superior and inferior (VCS and VCI) as well the left pulmonary veins (PV).

The right pulmonary veins are hidden by the right ventricle.

- Coronary arteries (orange): Main trunk of the left coronary artery (LCA) with the main branches Ramus circumflexus (RCX) and Ramus interventricularis anterior (RIVA) as well as the main trunk of the right coronary artery (RCA) with the main branches Ramus interventricularis posterior (RIP) and Ramus posterolateralis ( RPL).

The origin of the coronary arteries is incorrectly drawn in this drawing at the root of the pulmonary arteries and not in the area of the aortic root!

- The coronary veins are not shown.

The term coronary heart disease ( ancient Greek κορώνα korona : "crown", "wreath"; KHK, also ischemic heart disease , IHK) is a disease of the coronary arteries.

In most cases it is caused by arteriosclerosis (colloquially “hardening of the arteries”). Deposits in and not on the vessel walls cause stiffening of these and an increasing reduction in the cross-section of the vessel ( obstructive CAD ) up to complete blockage. The consequence of coronary sclerosis is an impairment of the blood flow and thus a reduced oxygen supply to the heart muscles . There is a disproportion between oxygen demand and oxygen supply, which is called myocardial ischemia (describes the effect on the muscles) or coronary insufficiency (describes the cause in the coronary vessels).

The main symptom of CHD is angina pectoris (chest tightness). As the disease progresses , the likelihood of accompanying symptoms such as cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure as well as acute life-threatening complications such as myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death increases .

CHD is a chronic disease that progresses over the course of years to decades. A cure, d. H. The elimination of the cause in the sense of removing the deposits in the affected vessel walls is currently not possible, but the increasing deterioration can be delayed or halted. There are a whole range of options for this, ranging from a change in diet to a change in lifestyle. Coronary artery disease can also be treated with drugs, therapeutic interventions using cardiac catheters, and surgically.

With its acute manifestations, CHD is the most common cause of death in industrialized nations.

definition

The term coronary artery disease is not defined uniformly by all authors in the literature. Coronary artery disease is defined in many textbooks and in the national health care guidelines of the German Medical Association as the manifestation of arteriosclerosis in the coronary arteries. There is also a somewhat broader definition. According to this, coronary artery disease arises from coronary insufficiency, which can have numerous other causes in addition to arteriosclerosis.

Epidemiology

Cardiovascular diseases , which include CHD, are by far the most common cause of death in industrialized nations . The CHD and its manifestations lead the death statistics. In Germany, more than 17 percent of all registered deaths in 2005 were caused by chronic CHD and myocardial infarction. The incidence of CHD is around 0.6% per year across all age groups, with an increase in the older age groups. In this context, incidence means that the disease manifests itself clinically. In about 50% of the cases the first event is a heart attack , in 10% sudden cardiac death and in the rest of the cases, by definition, unstable angina pectoris. About 2% of the population suffer from asymptomatic CHD, that is, a circulatory disorder of the heart without symptoms such as angina pectoris.

Causes and Disease Development

Whichever definition is used, atherosclerosis is the leading cause of coronary artery disease. Other causes very often occur in combination with arteriosclerosis. There are numerous risk factors for arteriosclerosis, the avoidance of which plays an important role in the prevention (prevention) of this disease.

Causes and development of arteriosclerosis

Atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) or atherosclerosis is the most common systemic disease of arteries. It is popularly known as hardening of the arteries. According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), arteriosclerosis is a variable combination of changes in the inner vessel wall ( intima ) of the arteries, consisting of focal accumulation of fatty substances, complex carbohydrates , blood and blood components, connective tissue and calcium deposits , combined with changes in the vascular muscle layer ( media ) .

These changes lead to hardening of the vessel walls, which is accompanied by a loss of elasticity, as well as narrowing of the vascular clearing due to wall thickening (arteriosclerotic plaques) and secondary thromboses . This restricts the blood flow to the heart muscle. Depending on the extent of the arteriosclerosis, the heart muscle can no longer be supplied with sufficient blood during physical stress and psychological excitement or even at rest (coronary insufficiency). The development of arteriosclerosis is a gradual, creeping and progressive process that lasts for many years to decades. Numerous risk factors favor the development of arteriosclerosis.

Risk factors of arteriosclerosis

The risk factors for the development of coronary arteriosclerosis in CHD and the corresponding vascular changes in other diseases, such as peripheral arterial occlusive disease , differ only insignificantly. However, there is a specific relationship between the risk factors and CHD, which is particularly important with regard to epidemiological data.

Risk factors include non-modifiable or constitutional risks such as genetic predisposition, the age and gender of the patient. The risk factors that can be influenced include lipid metabolism disorders in general and an increased cholesterol level (hypercholesterolemia) in particular, obesity , tobacco smoking, arterial hypertension (arterial high blood pressure), diabetes mellitus, sedentary lifestyle and psychosocial factors. The individual risk factors not only have an additive effect, but together increase the cardiovascular risk disproportionately ( synergistically ).

Hypercholesterolemia, together with tobacco smoking, arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus , is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for CHD in terms of morbidity and mortality . Several large studies have shown that the cardiovascular risk increases with an increase in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol as well as phospholipase A₂ . In contrast, HDL cholesterol has a cardioprotective effect. Smokers have, depending on the number of cigarettes smoked daily and the number of years, was where smoke ( cigarette pack-years , pack-years ) a 2-5-fold increased risk of suffering a heart attack. There is a linear relationship between blood pressure and the risk of developing CHD from systolic values above 125 mmHg and diastolic values above 85 mmHg, which means that above the blood pressure values mentioned, the risk increases proportionally with the increase in blood pressure. More than half of the patients with diabetes mellitus die from CAD. Compared to non-diabetics, diabetics have a 2-3 times higher risk of developing CHD.

Furthermore, radiation therapy as part of cancer therapy , e.g. B. breast cancer poses a risk of coronary heart disease. The risk increases depending on the organ dose of the heart by about 7.4% per Gray , with an increase in the risk after five years to over twenty years, without a threshold value and regardless of other cardiological risk factors.

Causes of Coronary Insufficiency

All of the following causes on their own and especially in combination with arteriosclerosis increase the likelihood of developing coronary artery disease. With regard to the pathophysiology , a distinction can be made between a reduction in the oxygen supply and an increase in the oxygen demand.

A reduction in the supply of oxygen can result, among other things, from a narrowing of the vascular lumen. In addition to arteriosclerosis, thromboses and embolisms , infectious or autoimmune inflammation of the vessels ( vasculitis ) and coronary spasms play a role as the cause . The latter can also by various drugs and drug abuse (eg in the case. Cocaine - abuse ) caused. External compression of the coronary arteries, for example in the case of cardiac hypertrophy or various tumors , also leads to a reduction in the supply of oxygen. In addition, hypoxemia (for example in anemia , respiratory failure and carbon monoxide poisoning ), in which the oxygen content in the blood is reduced, is a possible cause of coronary insufficiency. An increase in blood viscosity , as occurs in leukemia , is another rare cause.

An increase in oxygen demand occurs, among other things, in cardiac muscle hypertrophy, certain forms of cardiomyopathy , valvular heart disease , hyperthyroidism , high blood pressure, infectious diseases and fever . Physical strain and emotional stress also increase the need for oxygen. However, this stress only triggers coronary insufficiency if the corresponding diseases are present.

Clinical manifestations

The main symptom of CHD is angina pectoris . Synonyms are the short form AP symptoms and anginal complaints . Further symptoms are relatively unspecific for chronic CHD. In addition to the AP-symptoms often breathlessness (occur dyspnoea ), hypotension ( hypotension ), an increase in heart rate ( tachycardia ), increased sweating, pallor and agony on. It is not uncommon for CHD to be asymptomatic. This means that these patients have no symptoms of AP or other symptoms. This form of CHD is known as latent CHD or silent myocardial ischemia , and it is common in the elderly and diabetics. In the latter, diabetic polyneuropathy , which is caused by the impaired sugar metabolism , plays a decisive role. Diagnosing asymptomatic CHD is difficult. Since the patients do not feel pain with myocardial ischemia, heart attacks and other manifestations of CAD are often not noticed at all or too late.

Angina pectoris as the main symptom

Angina pectoris is typically dull, pressing, constricting and often burning pain that is localized behind the breastbone (retrosternal). Those affected often describe the pain as "tightness in the chest". It is also typical that the pain radiates to the left or, less often, to both arms. In addition, anginal complaints can show an atypical picture ( atypical angina pectoris ), that is, they can have a different pain character as well as a different pain localization and they can radiate to other parts of the body (neck, lower jaw, upper abdomen, back) or not at all. The mechanism by which pain is perceived (nociception) in ischemia has not yet been clarified with certainty.

A number of other diseases can also manifest themselves as chest pain .

Stable angina pectoris

There are different forms of angina pectoris. The stable angina pectoris is the leading symptom of chronic CAD. ( Chronic coronary syndrome used to be called stable CHD ). These are repetitive, short-term attacks of pain with the symptoms described above that occur during physical exertion. The heart muscle uses more oxygen in the process. However, the sclerotic coronary arteries cannot supply enough oxygen to the heart muscles. Stable angina pectoris occurs in the initial stage mainly during exertion and is therefore referred to as "exertion angina". After the end of the exercise, the patient is usually symptom-free again after a few minutes. An exception is a special form of stable angina pectoris, the so-called "walk-through angina". If the physical exertion is maintained over a longer period of time, the symptoms improve again with this form. In addition to physical strain, there are other causes that can trigger stable angina pectoris. This includes psychological excitement, cold and large meals. Another characteristic of stable angina pectoris is that the administration of nitrates (“nitro preparations”) leads to a rapid improvement in the pain during an attack. Nitro supplements cause blood vessels to widen . This increases blood flow in the heart muscle (and other organs) and eliminates the oxygen deficit that triggered the AP symptoms. Stable angina pectoris can be divided into different degrees of severity according to the CCS classification (classification of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society ). This is particularly important for the therapy of chronic CHD.

Unstable angina pectoris

Other forms must be distinguished from stable angina pectoris, in particular unstable angina pectoris, which can occur in the context of an acute coronary syndrome. Any angina pectoris that occurs for the first time in previously asymptomatic patients is classified as unstable angina pectoris. Unstable angina pectoris also refers to AP symptoms that occur at rest ("resting angina"), as well as AP symptoms that increase in intensity, duration and / or frequency ("crescendo angina"). The distinction between stable and unstable angina pectoris is of great differential diagnostic importance.

Buddenbrook Syndrome

The Buddenbrooks syndrome is a very rare but all the more dreaded misdiagnosis in dentistry. Toothache-like complaints in the lower jaw , preferably the left side, lead to a visit to a dentist . If a medical correlate can actually be found, for example a pulpid or devitalized , purulent tooth , the primary cause remains undetected, namely a coronary heart disease, which can be life-threatening.

Investigation methods

In the first place is the basic diagnosis. The diagnostic steps a doctor takes to diagnose chronic CHD depend on the manifestation of the CHD and its severity. The typical patient with chronic CHD usually suffers from stable angina pectoris. With the help of a detailed anamnesis with risk stratification, a physical examination, the evaluation of various laboratory parameters as well as the interpretation of a resting and exercise electrocardiogram, a relatively reliable suspected diagnosis can be made. An extended diagnostic procedure is usually not required.

In contrast, the diagnosis of asymptomatic CHD is difficult. The first manifestation of CAD in these cases is very often the acute coronary syndrome . However, regular visits to the family doctor with examinations tailored to the patient can help ensure that this form is detected in good time before a life-threatening complication occurs. In patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome, the diagnostic procedure differs significantly from that of chronic CHD.

If an obstructive CHD is suspected, the European guideline (as of 2019) recommends a CT angiography or a non-invasive ischemia test, possibly followed by an invasive coronary angiography.

Basic diagnostics

anamnese

The suspected diagnosis of CAD can often be made by taking a detailed anamnesis . If a patient suffers from the typical anginal symptoms, this is highly suspicious for the presence of CHD. In order to substantiate the suspicion, the patient should be asked as precisely as possible about the nature of the pain, existing risk factors, accompanying symptoms and other known diseases such as peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) and past strokes, the main cause of which is also arteriosclerosis. Patients with PAD or previous strokes also have an increased risk of developing CAD. In addition, a detailed family history should be taken in order to clarify whether there are known cardiovascular diseases in close relatives, as there could be a genetic predisposition that would increase the risk of chronic CHD. A precise history can rule out most differential diagnoses with a high degree of probability.

Physical examination

Examination findings characteristic of CHD can very rarely be obtained. The physical examination serves primarily to corroborate the suspected diagnosis and to reveal any accompanying diseases and risk factors. The examples given below represent only a small selection of possible test results. In this way, signs of hypercholesterolemia such as xanthelasma and xanthomas can be identified as risk factors. Cold legs and a lack of peripheral pulses can indicate peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD). Vascular noises , for example during auscultation of the external carotid artery , are also frequently found in arteriosclerosis. Auscultation of the heart can reveal other heart diseases, such as aortic stenosis, as the cause of the chest pain. Rattling noises during auscultation of the lungs, a visible congestion of the neck veins, lower leg edema and a palpable liver can indicate manifest heart failure. Palpation of the liver and certain changes in the eyes and ulcers of the lower legs ( ulcera crurum ) are often signs of overt diabetes (diabetes mellitus). A long-term high blood pressure can be revealed with an eye fundus . In the broadest sense, the physical examination also includes routine blood pressure measurement, which can be used to diagnose any high blood pressure, an important risk factor for CHD.

laboratory

Blood sugar , HbA1c , LDL -, HDL -, total cholesterol and triglycerides are determined for the detection of risk factors (diabetes mellitus and lipid metabolism disorders) . In addition, usually the small blood count , inflammation parameters and TSH . Outside of clinical practice, protein sample diagnostics can be carried out to determine the risk of atherosclerosis.

In the case of unstable angina pectoris and a suspected heart attack, the determination of cardiac enzymes is necessary. The heart-specific troponin is the first marker for acute ischemia . In the further course the creatine kinase (CK) and its heart-specific part (CK-MB) as well as glutamate-oxaloacetate-transaminase (GOT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) increase.

electrocardiogram

The EKG is a non-invasive examination method in which the electrical activity of the heart muscles is recorded with electrodes. There are essentially three different forms that are important in diagnosing chronic CHD. The resting ECG is part of the basic diagnosis. Exercise ECG and long-term ECG are carried out depending on the risk profile of the patient and the probability of the pretest.

Resting ECG

The resting ECG is part of the basic internal diagnostics, not only when coronary artery disease is suspected. However, the resting ECG is rather unsuitable for reliable detection of chronic CHD without a previous heart attack. There are signs that speak for a past infarction or a thickening of the heart muscle in the context of a high blood pressure disease. Cardiac arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation or frequent extra beats (ventricular extrasystole ) can also be seen, which can also be an indirect sign of the presence of CHD.

Exercise ECG

The exercise ECG is usually recorded with a bicycle ergometer , depending on the patient's condition, either lying down or sitting. It represents the next step in the diagnosis of suspected coronary heart disease. The sensitivity (50–70%) and specificity (60–90%) are significantly higher than with the resting ECG. How high is u. a. depending on the severity of the disease, gender and the extent of the load (reaching the maximum load heart rate). The suspicion of an existing chronic CHD is corroborated by disturbances in the regression of excitation during exercise, the increased occurrence of extra blows or a sudden drop in blood pressure during exercise.

Some heart medications ( digitalis glycosides ) make it more difficult to assess disorders of arousal regression, and the use of heart rate lowering drugs can limit the assessment because the target frequency is not reached and the patient is not fully utilized. The suspicion of an acute myocardial infarction is an absolute contraindication , and it should not be carried out even if the blood pressure or heart rate is significantly high prior to the examination.

Long-term ECG

If the results of the stress ECG are negative, but the suspected diagnosis of chronic CHD still exists, a long-term ECG can be useful. It can be particularly helpful for uncovering silent ischemias. There is a high probability of a positive test result if there are repeated ST segment depressions that last longer than 1 minute. In practice, the long-term ECG is rarely used for this indication.

Echocardiography

As part of the ultrasound examination of the heart, wall movement disorders can be seen, which persist in the form of a scar after a heart attack has ended. Various other diseases of the heart ( valves , heart muscle ) can also be recognized.

Doppler sonography of the vessels

Doppler sonography of the vessels, usually the carotid arteries , can be performed from the point of view that all vessels in the body are affected to the same extent by atherosclerosis . If changes can be seen here, the probability is high that in other places, such as B. the coronary arteries, there are also changes.

Risk stratification

In the synopsis of the findings collected, the further diagnostic procedure is planned as part of a risk stratification . A decision has to be made as to whether the complaints

- most likely not come from the heart, then other causes must be investigated,

- they tend not to come from the heart and one makes further non-invasive diagnostics, or

- the probability of the presence of a relevant CHD is assessed as rather high to certain .

The point system of the Euro Heart Survey is a valuable aid , with points being awarded for risk factors, the severity of stable angina pectoris and comorbidities.

| Risk factor | Points |

|---|---|

| One or more comorbidities | 86 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 |

| Severity of angina pectoris | |

|

0 |

|

54 |

|

91 |

| Symptoms> 6 months CCS III | 80 |

| Impaired left ventricular function | 114 |

| ST segment depression or T negativity in the ECG | 34 |

Advanced diagnostics

The further diagnosis of a suspected coronary heart disease pursues two goals: on the one hand, the detection of load-dependent wall movement disorders of the heart chambers. If these are present, there is a high probability that the vessel supplying the wall section with blood is narrowing and that the blood flow is insufficient under the load. Stress echocardiography, myocardial scintigraphy and, recently, magnetic resonance imaging of the heart (cardio MR) are used for this. The second goal is to display the coronary vessels as evidence of the suspected vascular narrowing, traditionally with the help of coronary angiography and, more recently, also non-invasively with a computed tomography of the heart.

Stress echocardiography

In stress echocardiography , the heart muscle is shown under stress using ultrasound imaging. The stress is generated, similar to the stress EKG, by cycling while lying down or by means of medication. In the case of clinically relevant stenosis, the stress should trigger a wall movement disorder.

Myocardial scintigraphy

Myocardial scintigraphy is a nuclear medicine examination method , the main indication of which is the detection of CAD with a medium probability. The radionuclide used is 201 thallium or 99m technetium , each of which is injected intravenously . Myocardial scintigraphy can be used to determine the extent, severity and location of the ischemia and to make statements about the patient's prognosis. Myocardial scintigraphy is superior to exercise ECG in terms of sensitivity and specificity, especially in the presence of a 1-vascular disease.

To diagnose CHD, myocardial scintigraphy is initially performed on a bicycle ergometer if there are no contraindications. Alternatively, if physical strain is not possible, it can be induced pharmacologically, for example with the vasodilators adenosine and dipyridamole or the catecholamine analogue dobutamine . In healthy people, the blood flow can be increased considerably under stress, in CHD patients there are blood flow deficits in certain areas, depending on the coronary arteries affected. After a break of several hours, another scintigram is made, but without stressing the patient. During this time, the blood flow has normalized, so that the tracer is evenly distributed in the heart muscle. If the same areas are found to have reduced accumulation, there is a high probability of irreversible myocardial ischemia, i.e. an infarct scar that was caused by a previous heart attack.

The examination with 201 thallium can provide information about the vitality of the heart muscle in addition to statements about blood flow.

Myocardial scintigraphy with 99m technetium can be performed as cardiac phase-triggered recording because of the better yield, provided there are no pronounced cardiac arrhythmias. This allows the function of the left ventricle to be assessed under stress and at rest, and the end-systolic and end-diastolic volume and the ejection fraction can be determined indirectly. CHD patients experience cardiac wall movement disorders during exercise and the ejection fraction decreases.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart

Cardio-MR is a relatively new, time-consuming, not very common examination method that will possibly supplant myocardial scintigraphy in the foreseeable future. Here, under drug exposure, wall movement disorders are also searched for, and statements can also be made about the pumping capacity and past inflammations of the heart muscle. If no wall movement disorder is seen, coronary heart disease can be ruled out with almost 100% certainty.

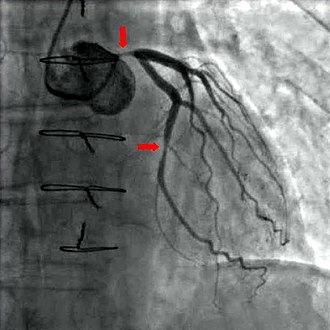

Coronary angiography and ventriculography

With the help of diagnostic coronary angiography , coronary arteries can be visualized and their anatomy as well as the extent and location of any stenoses assessed. It is the most informative study. During this examination, a cardiac catheter is advanced through the arteria femoralis (thigh artery) or, more rarely, the arteria brachialis (upper arm artery) to the branches of the coronary arteries from the aorta and contrast medium is injected into the branches . With the help of X-rays , the coronary arteries can be visualized and assessed. The catheter can be advanced further into the left ventricle by bridging the aortic valve. This exam is called a ventriculography . It also enables regional contraction disorders to be made visible, which can provide information about previous heart attacks, for example, as well as an assessment of the left ventricular pump function by calculating the ejection fraction and determining the elasticity of the heart muscles ( compliance ) by determining the end-diastolic volume .

Since coronary angiography and ventriculoangiography are invasive examination methods, in addition to relatively harmless complications ( e.g. hematomas at the injection site), in very rare cases serious life-threatening complications can occur. These include, above all, heart attacks, strokes , splits (dissections) of the vessel walls, heart ruptures , air embolisms and arrhythmias . The lethality of the examination is below 1: 1000.

Due to the risk of complications, radiation exposure and the stress on the kidneys caused by the X-ray contrast agent, which cannot be completely ruled out, the indication of coronary angiography for the diagnosis of chronic CHD should be made relatively strict and weighed up in terms of a risk-benefit analysis. According to the recommendations of the National Health Care Guideline (NVL), this examination should only be carried out if either all non-invasive examination methods have been exhausted without results and the suspected diagnosis of chronic CHD is still probable, or if the patient could benefit from revascularization measures. In the weighing up, existing cardiovascular risk factors, past heart attacks and other existing cardiovascular diseases, the assessment of the patient's quality of life and the severity of stable angina pectoris according to the CCS classification also play an important role. For the latter, there is usually no indication for a new coronary angiography with a CCS stage <III or with successful conservative pharmacotherapy.

Computed tomography of the heart

Cardio-CT, like cardio-MRT, is a new, not yet established examination method. Here, an X-ray slice image of the heart is made, in which the calcium score is first determined, i.e. H. the amount of lime in the captured area. If this exceeds a certain limit value, the examination is terminated, since the informative value regarding constrictions in the coronary vessels is too low. If the investigation can be continued, the informative value about the extent of CHD is quite good. Since a cardiac catheter examination usually has to be followed up when diagnosing CAD with cardio-CT, the indication should be narrowed down solely for reasons of radiation hygiene. Patients come into question here, in whom there is little evidence to suggest the presence of CHD, but cannot be excluded with absolute certainty using non-invasive methods. The quantification of the coronary calcifications in the CT is carried out with the CACS (Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring), which was described in 1990 by Agatston and colleagues.

prevention

Under prevention or prophylaxis refers (in medicine measures that can prevent damage to a healthy organism primary prevention ), uncover the symptomless disease early stages so that they can be treated early ( secondary prevention ) and avoid measures that relapses of disease or progression of Can slow down the disease ( tertiary prevention ). In the case of CHD, the transitions between the various forms of prevention are fluid, so that a strict distinction is not made in this article.

Risk factor management plays a major role in the prevention of CHD. This refers to measures that can reduce or better avoid risk factors. In order to reduce risk factors, lifestyle changes in the patient and possibly prevention with medication are necessary. The drug therapy of concomitant diseases such as high blood pressure , diabetes mellitus and lipid metabolism disorders is therefore indirectly part of prevention , since these are also risk factors.

change of lifestyle

CHD patients can make an important contribution to positively influencing the course of their disease by changing their lifestyle. The promising lifestyle changes include quitting smoking, a targeted change in diet and weight reduction if you are overweight.

The smoking is one of the major cardiovascular risk factors. Smoking cessation can reduce the risk of cardiovascular events by up to 50%.

The effect of a targeted change in diet goes beyond the mere lowering of the cholesterol level. The standard should be the so-called Mediterranean diet, which is characterized by high-calorie, high-fiber and low-fat food and is also rich in unsaturated and omega-3 fatty acids . In addition to nutrition, regular physical activity also has a positive effect.

The severity of the excess weight can be documented by measuring the body mass index (BMI) and the waist circumference . The degree of severity correlates with the frequency and prognosis of coronary artery disease and other diseases, especially type 2 diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, heart failure, lipid metabolism disorders and blood clotting disorders .

In an overview article on secondary prevention in CHD, the Deutsches Ärzteblatt draws the following conclusion: "The total effectiveness of the lifestyle changes listed is likely to be several times greater than the effectiveness of a combined drug therapy." Attending a cardiac school can be useful for permanent lifestyle changes .

| Lifestyle change | Ref. | ARR% | Duration of study (years) | Number of study participants | NNT / 1 year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| quit smoking | 7.7 | 4.8 | 5878 | 62 | |

| low-fat diet | 16 | 3 | 100 | 19th | |

| low-fat diet | 38 | 12 | 100 | 32 | |

| "Mediterranean" food | 12 | 4th | 605 | 33 | |

| Recreational sport | 2.2 | 3 | 4554 | 136 | |

| Stress management | 20.9 | 5 | 107 | 24 |

Reduced-fat diet: <20% fat content. Studies with <30% showed no benefit.

“Mediterranean” food: bread, vegetables, fruit, fish, unsaturated fatty acids, olive oil; little meat.

Compensatory sport: at least 3x / week, 30 min.

ARR = absolute risk reduction for death and non-fatal myocardial infarction; NNT = number needed to treat .

Drug prevention

Antiplatelet drugs

Platelets (blood platelets) are cells without a nucleus that play an important role in blood clotting (hemostasis). By inhibiting platelet aggregation , the likelihood of thrombosis in the coronary arteries is reduced. The risk of developing an acute coronary syndrome or dying of a heart attack is reduced.

The most common anti-platelet drugs include acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and clopidogrel . The agent of choice is ASA because the benefit for the patient, both without and with a previous myocardial infarction, in terms of mortality and morbidity compared to other platelet aggregation inhibitors is at least equivalent. The dosage depends on the patient's cardiovascular risk profile. In patients with a high cardiovascular risk or with stable angina pectoris, the mortality rate falls under ASA medication. Clopidogrel is indicated in the event of contraindications or ASA intolerance.

Cholesterol lowering drugs

Medicines from the group of statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase , an enzyme in the cholesterol metabolism, and thus the body's own cholesterol production. They are also assumed to have a certain stabilization of atheromatous plaques.

Vitamin D

In the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, the risk of myocardial infarction in men with vitamin D deficiency (plasma 25-OH-vitamin D of 15 ng / mL or less) was 2.4 times higher than in those of the same age with adequate Vitamin D supply (plasma 25 (OH) D of at least 30 ng / mL). Even taking into account CHD risk factors such as a positive family history, hypertension, poor lipid profile, and obesity, the risk of myocardial infarction was still doubled with low vitamin D levels. These study data were collected from 18,225 men between the ages of 40 and 75 whose blood had been examined. At the start of the study, none of the men had CHD. Over the next ten years, 454 study participants had suffered a non-fatal heart attack or a fatal CHD event. In another study with more than 3000 men and women, those with low vitamin D values (median 7.7 and 13.3 ng / ml) had both cardiovascular and total mortality rates doubled within 7.7 years. Participants with a good vitamin D supply (median 28.4 ng / ml) were used for comparison.

Life's Simple 7

The American Heart Association has created 7 basic rules that should prevent not only cardiovascular disease, but cancer as well.

- Be physically active

- maintain a healthy weight

- eating healthy

- maintain healthy cholesterol levels

- Keep blood pressure low

- maintain normal blood sugar

- do not smoke

treatment

In the case of a disease of the small vessels , apart from drug therapy, no invasive treatment method has so far been promising. In the case of disease of the large vessels, it is possible to dilate it with a balloon catheter or to perform a bypass operation . The statutory health insurances have been offering disease management programs (DMP) since mid-2004 to ensure consistent quality of therapy .

Medical therapy

Nitrates

By reducing the vascular resistance, nitrates lead to a lowering of the preload and the afterload of the heart. This reduces the oxygen consumption of the heart muscle. There are both short-acting and long-acting nitrate supplements. Short-acting nitrates are used for the symptomatic treatment of acute angina pectoris. The effect occurs within a few minutes with sublingual or cutaneous application, so that they are particularly suitable for treatment in acute AP attacks. Short-acting and long-acting nitrates have no influence on the prognosis of chronic CHD. Long-acting preparations are used for long-term therapy, although they are only suitable to a limited extent due to the rapid development of tolerance. With specific therapy schemes and therapy breaks lasting several hours, long-term therapy with nitrates is possible if the patient is in compliance.

Beta blockers

Beta blockers lower the heart rate both at rest and during physical exertion (negative chronotropy ). In addition, they have a negative inotropic effect by lowering the contractility (force of contraction) of the heart. Both mechanisms cause the oxygen demand of the heart muscles and the arterial blood pressure to decrease. Beta blockers, like nitrates and calcium channel blockers, can be used against anginal complaints. In contrast to the other two drugs, they also lower the risk of cardiovascular events. Beta blockers are the drug of choice for stable angina pectoris. As with all drugs, the contraindications must be observed. Here these are in particular bronchial asthma and various cardiac arrhythmias , such as AV blockages .

Calcium channel blockers

The calcium antagonists (actually calcium channel modulators) reduce the calcium influx into the muscle cell and inhibit the electromechanical coupling . This leads to a decrease in the contractility and oxygen consumption of the heart.

Trapidil

The drug Trapidil , which has been approved in Germany since 1992, is suitable for the treatment of CHD, especially in patients who are intolerant to the nitrates used as standard.

Revascularization Therapy

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and stent placement

As a diagnostic and therapeutic measure, the depiction of the coronary arteries using coronary angiography is considered the gold standard in diagnostics. In the same session it is possible to expand significant constrictions by means of balloon dilatation ( percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty , PTCA), possibly combined with the implantation of a stent .

Bypass surgery

In a bypass operation , vascular grafts are used to bridge the constrictions from veins or arteries previously removed from the extremities; in addition, an artery running inside the thoracic cage, the left internal thoracic artery ( LIMA ) (rarely also the right one), is overlaid with a branch of the coronary arteries connected to the bottleneck. As a rule, the operation is performed in cardiac arrest with a heart-lung machine ; Under certain conditions, however, an operation on the beating heart (so-called off pump bypass ) or minimally invasive techniques are possible.

Indications

According to the recommendations of the national care guideline, there is an indication for revascularization therapy in the following cases:

- In the case of CHD, the symptoms of which cannot be brought under control with drug therapy alone, revascularization therapy can bring about a significant alleviation of the AP symptoms. Due to its lower invasiveness, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty is the therapy of first choice.

- In the case of moderate stenoses (> 50 percent) of the main trunk of the left coronary artery, bypass surgery is the treatment of first choice because it is superior to percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in terms of improving quality of life and prognosis as well as the occurrence of acute CHD manifestations. However, if the patient is inoperable or refused, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty is recommended. Inoperability can exist due to severe comorbidities or diffuse arteriosclerosis.

- Severe proximal stenoses (> 70 percent) of the ramus interventricularis anterior (RIVA stenosis) should be treated with revascularization therapy regardless of the symptoms, whereby percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and bypass surgery are regarded as equivalent in terms of improving the prognosis. If there is also a significant reduction in the ejection capacity of the left heart, according to current studies, there are advantages for bypass surgery.

- In the case of multivascular disease, the AP symptoms can be significantly reduced by revascularization therapy, regardless of the method. An improvement in the prognosis compared to drug therapy alone has not been proven.

- In three-vessel disease with severe proximal stenoses, bypass surgery is recommended as the therapy of first choice. Both revascularization methods improve the quality of life (reduction of symptoms) and probably also lead to an improvement in the prognosis.

history

The people in ancient Egypt already suffered from arteriosclerosis or coronary heart disease, as was shown by studies on mummies in the 20th and 21st centuries. In 1749, hardening of the arteries was first described by Jean-Baptiste Sénac . The first and very precise description of the AP symptoms goes back to the English physician William Heberden in 1768. Heberden did not recognize that there is a connection between angina pectoris and arteriosclerosis of the coronary arteries. This connection was also described in 1768 by Edward Jenner and in 1799 by Caleb Hillier Parry . With their work , Antonio Scarpa (1804) and Jean-Frédéric Lobstein (1833) have made a major contribution to today's knowledge of macroscopic and microscopic vascular changes caused by arteriosclerosis . Wean in 1923 and Himbert and Jean Lenègre in 1957 recognized the ECG changes that can occur in the context of chronic CHD .

CHD in animals

In animals, arteriosclerotic changes in the coronary vessels or chronic CHD have only very little clinical significance; There is also no corresponding documentation, especially for large animals. In small animals, there are some studies on arteriosclerosis and its manifestation myocardial infarction. Systemic arteriosclerosis was diagnosed in an autopsy from 1970 to 1983 in 21 dogs. In addition, histological examinations revealed infarct areas in the heart muscles. In other studies with dogs, similar changes were found, including those in the coronary arteries. In addition, there are systemic changes in the vessels in cats, the significance of which for the coronary vessels is currently unclear.

The heart of the domestic pig is similar in its anatomical structure and its physiology to that of humans. Complex clinical pictures of arteriosclerosis already appear at the age of about four to eight years, which, however, is usually far longer than the normal lifespan of the animals due to the fact that they are kept as farm animals. In the event of illness, ischemic changes and damage comparable to those of humans occur within a relatively short period of time. The coronary arteries also tend to develop collateral vessels to an even lesser extent than those of humans , which facilitates the clinical localization of infarct areas. Because of these properties, pig hearts are used as models for studying human chronic myocardial ischemia. Rat , rabbit , dog and primate hearts are also used for this purpose .

literature

- Chronic CHD . - National care guidelines of the German Medical Association (BÄK), the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV) and the Working Group of Scientific Medical Societies (AWMF) (as of April 2019)

- Hans H. Lauer: History of coronary sclerosis. BYK Gulden, Konstanz 1971. (From the Institute for the History of Medicine at the University of Heidelberg)

- JO Leibowitz: The history of coronary heart disease. Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, London 1970.

- Martin Ruß, Jochen Cremer u. a .: Differential therapy of chronic coronary artery disease: when is drug therapy, when percutaneous coronary intervention, when aortocoronary bypass surgery? In: Dtsch Arztebl Int. Volume 106, Number 15, 2009, pp. 253-261. doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2009.0253

Web links

- Heart in danger? - Causes, prevention, therapy - results of cardiovascular research . (PDF; 3.8 MB) Federal Ministry of Education and Research, 2006; brochure

- Heart attack risk calculator from the German Heart Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f M. Classen, V. Diehl, K. Kochsiek: Internal medicine. 5th edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-437-44405-0 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g H. Renz-Polster u. a .: Basic textbook internal medicine. 3. Edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-437-41052-0 .

- ↑ Cause of death statistics: Federal health reporting

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Chronic KHK , Version 1.8, April 2008. (PDF) National care guidelines of the German Medical Association

- ↑ a b Manfred Dietel u. a. (Ed.): Harrison's Internal Medicine. German Edition of the 15th edition. ABW Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-936072-10-8 .

- ↑ Bethesda: NHLBI morbidity and mortality chartbook . National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, May 2002. nhlbi.nih.gov

- ↑ Europe in figures - Eurostat yearbook 2006-07 . (PDF; 12.1 MB)

- ↑ Causes of death in Germany. Federal Office of Statistics

- ^ R. Ross: Atherosclerosis – an inflammatory disease. In: The New England Journal of Medicine . Volume 340, Number 2, January 1999, pp. 115-126, ISSN 0028-4793 . doi: 10.1056 / NEJM199901143400207 . PMID 9887164 . (Review).

- ↑ J. Stamler et al. a .: Is relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356,222 primary screees of the multiple risk factor intervention trial. (MRFIT). In: JAMA. 256, 1986, pp. 2823-2828.

- ↑ W. Verschuren et al. a .: Serum total cholesterol and long-term coronary heart disease mortality in different cultures. Twenty-five-year follow-up of the seven countries study. In: JAMA . 274, 1995, pp. 131-136.

- ↑ Coronary artery disease: markers of inflammation as responsible as high blood pressure and LDL cholesterol. In: The Lancet . April 30, 2010.

- ^ The Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. In: The Lancet . 375, 2010, p. 1536. doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 60319-4

- ↑ A. Rieder: Epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases . (PDF) In: Journal for Cardiology. 11 (Supplementum D), 2004, pp. 3-4.

- ↑ Sarah C. Darby, Marianne Ewertz, Paul McGale, Anna M. Bennet, Ulla Blom-Goldman, Dorthe Brønnum, Candace Correa, David Cutter, Giovanna Gagliardi, Bruna Gigante, Maj-Britt Jensen, Andrew Nisbet, Richard Peto, Kazem Rahimi , Carolyn Taylor, Per Hall: Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Women after Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer. In: New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 368, Issue 11, March 14, 2013, pp. 987-998, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1209825 .

- ↑ Nadine Eckert, Kathrin Gießelmann: Chronic coronary syndrome. Too few ischemia tests. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 51–52, December 23, 2019, pp. B 1971–1973.

- ↑ Nadine Eckert, Kathrin Gießelmann: Chronic coronary syndrome. Too few ischemia tests. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 116, Issue 51–52, December 23, 2019, p. B 1971–1973, here: p. B 1972.

- ↑ a b c d R. Dietz u. a .: Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic coronary heart disease of the German Society for Cardiology (DGK). In: Journal of Cardiology. 92, 2003, pp. 501–521, leitlinien.dgk.org (PDF)

- ↑ a b c C. A. Daly et al. a .: Predicting prognosis in stable angina-results from the Euro heart survey of stable angina: prospective observational study . Online version. In: BMJ . 332 (7536), 2006, pp. 262-267.

- ↑ Eur J Echocardiogr. 9 (4), Jul 2008, pp. 415-437.

- ↑ Büll, Schicha, Biersack, Knapp, Reiners, Schober: Nuclear medicine. Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-13-128123-5 , pp. 213f.

- ↑ MA Pantaleo, A. Mandrioli u. a .: Development of coronary artery stenosis in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. (PDF; 287 kB) In: BMC Cancer. 12, 2012, p. 231 doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2407-12-231 ( Open Access )

- ↑ Kauffmann u. a .: Radiology, 3rd edition. Urban & Fischer, Munich / Jena 2006, ISBN 3-437-44415-8 .

- ↑ AS Agatston, WR Janowitz, FJ Hildner, NR Zusmer, M Viamonte, R Detrano: Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. In: J Am Coll Cardiol . tape 15 , no. 4 , 1990, pp. 827-832 , PMID 2407762 .

- ↑ B. Hermanson et al. a .: Beneficial six-year outcome of smoking cessation in older men and women with coronary artery disease. Results from the CASS registry. In: N Engl J Med. 319, 1988, pp. 1365-1369

- ↑ L. Ignarro, M. Balestrieri, C. Napoli: Nutrition, physical activity, and cardiovascular disease: An update. In: Cardiovascular Research. 73, 2007, p. 326, doi: 10.1016 / j.cardiores.2006.06.030 .

- ↑ KD Kolenda: Secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: efficiency demonstrable . (PDF) In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. 102/2005, p. A1889.

- ↑ K. Wilson, N. Gibson, N. Willan, D. Cook: Effect of smoking cessation on mortality after myocardial infarction. In: Arch Int Med . 160, 2000, pp. 939-944.

- ↑ a b L. M. Morrison: Diet in coronary atherosclerosis. In: JAMA. 173, 1960, pp. 884-888.

- ↑ M. De Longeril, P. Salen, JL Martin, J. Monjaud, J. Delaye, N. Mamelle: Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction. Final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. In: Circulation . 99, 1999, pp. 779-785. PMID 9989963

- ^ GT O'Connor, I. Buring, S. Yusuf et al. a .: An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. In: Circulation. 80, 1989, pp. 234-244.

- ↑ JA Blumenthal, W. Jiang, MA Babyatz u. a .: Stress management and exercise training in cardiac patients with myocardial ischemia. In: Arch Intern Med. 157, 1997, pp. 2213-2223.

- ↑ E. Giovannucci, Y. Liu et al. a .: 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. In: Archives of internal medicine. Volume 168, Number 11, June 2008, pp. 1174-1180, ISSN 1538-3679 . doi: 10.1001 / archinte.168.11.1174 . PMID 18541825 .

- ↑ H. Dobnig, S. Pilz u. a .: Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. In: Archives of internal medicine. Volume 168, Number 12, June 2008, pp. 1340-1349, ISSN 1538-3679 . doi: 10.1001 / archinte.168.12.1340 . PMID 18574092 .

- ↑ Quoted from the Ärzte-Zeitung. July 9, 2008, p. 1.

- ↑ LJ Rasmussen-Torvik, CM Shay, JG Abramson, CA Friedrich, JA Nettleton, AE Prizment, AR Folsom: Ideal Cardiovascular Health is Inversely Associated with Incident Cancer: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. In: Circulation. doi: 10.1161 / CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001183 .

- ↑ HP Wolff, TR Weihrauch: Internal Therapy 2004-2005. 15th edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-437-21802-6 .

- ↑ J. Schmitt, M. Beeres: History of Medical Technology, Part 3. In: MTDialog. Dec. 2004, pp. 72-75. bvmed.de ( Memento from July 31, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Martin Schrenk: From the history of cardiopathology: Die Heberden's Angina pectoris (1768). Mannheim / Frankfurt am Main 1969.

- ↑ R. RULLIERE: history of Cardiology in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: R. Toellner: Illustrated history of medicine. Volume 3, Andreas Verlag, Salzburg 1992, ISBN 3-86070-204-1 .

- ^ S. Liu et al. a .: Clinical and pathologic findings in dogs with atherosclerosis: 21 cases (1970-1983) In: J Am Vet Med Assoc. 189 (2): Jul 15, 1986, pp. 227-232. PMID 3744984

- ↑ D. Kelly: Arteriosclerosis of coronary arteries in Labradors with congestive heart failure. In: J Small Anim Pract. 33, 1992, p. 437.

- ↑ D. Detweiler: Spontaneous and induced arterial disease in the dog: pathology and pathogenesis. In: Toxicol Pathol . 17 (1 Pt 2), 1989, pp. 94-108. PMID 2665038

- ↑ V. Lucke: Renal disease in the domestic cat. In: J Pathol Bacteriol. 95 (1), Jan 1968, pp. 67-91. PMID 5689371

- ↑ C. Nimz: Pathological-anatomical and immunohistological investigations of the ischemic pig myocardium. Vet.-med. Diss., Munich 2004, pp. 1-10 online version