Tobacco smoking

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F17.1 | Mental and behavioral disorders from tobacco (harmful use) |

| F17.2 | Mental and behavioral disorders caused by tobacco (addiction syndrome) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Tobacco smoking (short: smoking ) is the inhalation of tobacco smoke , which is produced by burning (actually glowing ) tobacco-containing products such as cigarettes , cigarillos or shisha tobacco .

Cigars and pipes are actually " puffed ", although one often speaks of smoking in colloquial terms. The transition is fluid, sometimes tobacco smoke is puffed from water pipes or cigarillos, sometimes inhaled.

Since the harmful effects of smoking and passive smoking have been scientifically proven, the topic has been increasingly noticed and discussed. According to the World Health Organization , over 6 million people die each year as a result of tobacco consumption, around 10% of them from secondhand smoke. The annual economic damage is estimated at around $ 950 billion. In total, around 1.1 billion people smoke.

History of smoking

Smoking had long been common in various ancient American cultures and was practiced there primarily as a ritual. The oldest representations of smoking Maya priests are from 600 to 500 BC. Known. The Mayan priests lit sacred fires and then inhaled the tobacco smoke. After the discovery of America by Columbus , who on November 6th 1492 documented for the first time the tobacco consumption of locals on what is now the island of Cuba , first reports about the tobacco plant in Europe appeared in 1497 . Tobacco later made its way to Europe, where other plants may have been smoked (for example lavender ). Europeans first inhaled tobacco smoke through their noses .

Soon smoking was so widespread that Tsar Mikhail Romanov stopped tobacco consumption in the 16th and 17th centuries. Attempted to combat penalties such as exile, excommunication and execution in the 19th century - while the tobacco tax was first introduced elsewhere in 1625 . From the early 19th century onwards, smoking was again largely accepted socially and positively viewed as a means of expressing social rank, composure and superiority. In the context of the revolutions of 1848/1849 , smoking bans were considered an expression of the arbitrariness of the princes , while the “right to smoke in public” was considered an “achievement”.

In the “Third Reich”, health policy measures against smoking were taken, including the propagated statement “The German woman does not smoke”, which, although not able to prevent the general increase in tobacco consumption, reduced the proportion of women among smokers. After the war, the measures against smoking came to a temporary end. The US company Philip Morris tried to discredit smoking bans in advertisements with this “Nazi connection” (comparison of non-smoking areas with Jewish ghettos ), but without success.

The clear link between tobacco smoking and the risk of developing lung cancer ("lung cancer") and coronary artery disease was first scientifically proven in a groundbreaking epidemiological study by the Royal College of Physicians in the UK in 1962. This connection had previously been suspected several times, but had not been scientifically proven. At the time these study results were announced, around 70% of all men and 40% of women in the UK were smokers, and smoked was literally everywhere regardless of non-smokers, on public transport, airplanes, in the workplace, even in schools and hospitals. With the increasing spread of medical knowledge about the harmful effects of smoking, the general assessment of smoking has turned strongly towards the negative. While smoking was particularly widespread in the upper class in the 1960s, it is now the case that low-wage earners tend to smoke. People in public life today usually avoid confessing to smoking in order to be seen as role models .

Smoking and social classes

The proportion of smokers is comparatively higher in groups with low education or with low socio-economic status. According to a report by the World Health Organization (WHO), this was confirmed by studies from India, Poland and Great Britain, among others. In addition, smoking rates are higher in low and middle income countries than in high average income countries.

In the mid-1960s, the proportion of smokers in the upper and middle classes in Germany was still more than 40%, by 2010 it had more than halved in the upper class and was only 19%, in the middle class it was around one Third dropped to 29%. In contrast, cigarette smoking is just as widespread among the lower social classes today as it was in the mid-1970s, at around 34%.

According to a study published in 2004 by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) with data from 1998, the proportion of smokers among men with an income of less than € 730 per month in Germany at that time was 43%; for men with an income above € 3,350 the proportion was only 23%. Around 50% of people who do simple, manual activities smoked. In contrast, the proportion of smokers in the group of doctors and high school and university teachers was around 15%. Social differences in smoking behavior are also evident in young people. According to a study carried out by the BZgA in Germany in 2015, around 3% of secondary school students and total school students smoke, but 8.5% of secondary school students and 9.3% of secondary school students smoke. Among older adolescents, 18.7% of the upper secondary level of the grammar school and 16.5% of the students smoke, but 32.1% of the vocational school students and 36.1% of the trainees.

The Federal Statistical Office also confirmed in 2006: Among people with a degree from a university / doctorate, the proportion of smokers is only 16% (men 18%, women 14%). A representative study by the Heinrich Heine University in Düsseldorf, based on the German survey on smoking behavior (DEBRA) published in 2018, confirmed the social gradient in smoking behavior: 42% of all Germans over 14 years of age who have no school-leaving certificate smoke only 20% of all Germans with a high school diploma. The proportion of smokers and the social gradient in smoking are more pronounced in Germany than in other western and northern European countries.

The 1995 microcensus data showed that the male occupations with the highest smoking rate included construction workers (54%), road builders (52%), transport workers (52%), roofers (51%) and professional drivers (40%). Among the occupations with the lowest smoking rate, there was only one manual occupation, namely farmer (17%). Other occupations with a low smoking rate were electrical engineer (17%), elementary school teacher (16%), university teacher (15%) and high school teacher (13%). Among women, the highest smoking rates were found among innkeepers (45%), geriatric nurses (36%), cashiers (35%), housekeepers (35%) and nurses (34%) and the lowest smoking rates among teachers (16%) , Primary school teachers (15%), doctors (11%), high school teachers (11%) and farmers (9%).

The relative share of expenditure on tobacco products in 1998 was greater in financially weak households than in financially strong households. In low-income groups, especially single parents, this proportion could amount to up to 20% of disposable income.

One explanatory model for the high smoking rate among less educated people is the model of the gratification crisis developed by Johannes Siegrist . According to this model, employees with low qualifications, such as construction workers, often get into an emotional crisis. They exhaust themselves professionally, but still get little recognition from society. The emotional crisis can lead to increased smoking. According to another explanation, people with a relatively low level of education generally tend to evaluate health as an uncontrollable happiness and less as a result of their own actions and measures against smoking, less as care than as harassment. Groups with a common socialization , which also includes confirmation of group membership through smoking, developed the feeling of being a “ discriminated minority”. This feeling is reinforced by the fact that members of the higher classes in particular advocate restrictions on smoking and openly show their disapproval to smokers.

Children, adolescents and young adults

The number of 12 to 17 year olds who smoke constantly or occasionally fell from 30% in 1979 to 8% in 2015.

In 2012, the WHO published data on the smoking behavior of young people in 41 countries from the international HBSC study on the health behavior of children and adolescents of school age, which is supervised by Bielefeld University in Germany . Around 1,500 young people were surveyed in each country in three age groups (11, 13, 15 years). In Germany, 15% of 15-year-old boys and girls stated that they smoke at least once a week. In Austria it was 25% of boys and 29% of girls, in Switzerland 19% of boys and 15% of girls. By far the highest smoking rates among 15-year-olds were found in Greenland (53% boys and 61% girls), followed by Lithuania (34% and 21%) and Austria, the lowest in Iceland (9% and 7%) and Armenia (11% and 1%).

For Germany, Austria and Switzerland, as well as for most Central European countries, the study finds an inverse relationship between tobacco consumption and prosperity. Young people from less well-off families are described as particularly at risk, which the authors attribute in part to the parental model.

In 2012 the members of the Federal Association of German Tobacco Wholesalers and Automatenaufsteller e. V. (BDTA) operated 360,000 machines, 20,000 fewer than two years earlier. There are around 5000 of them in Austria. The use of cigarette machines is now banned in Great Britain. In other countries such as Hungary, France or Ireland, cigarette machines are no longer allowed in public.

According to a comparative study from 2006, 25.1% of medical students and 20.6% of medical students at the University of Göttingen smoked , while in London the corresponding figures were only 10.9% and 9.1%.

In Austria, it has been forbidden to smoke in a car since May 1, 2018 if minors are also in the car.

In Italy, on the basis of a decree of January 12, 2016, it has been forbidden to smoke in a car since February 2016 if there are minors or pregnant women there. The fine is between 25 and 250 euros, but it is doubled and can reach up to 500 euros if smoked in the presence of a woman whose pregnancy is evident, a nursing mothers or children up to 12 years of age.

Smoking and family

Evaluations of representative data from 1998 by the German Cancer Research Center Heidelberg (DKFZ) yielded the following family-related results: Parents smoke more often than childless couples. Young parents smoke particularly often. Half of all children under the age of six and around two thirds of all children aged 6 to 13 live in households in which at least one person smokes. In the lower social class, three out of four households with children under six years of age smoke. In the upper layer it is only a third. There is also a social trend in the smoking behavior of pregnant women. In the upper class, 24% smoke and in the middle class 17% of pregnant women. In the lower layer it is 40%.

Religious view of smoking

Various Christian fundamentalist or other religious groups are of the opinion that tobacco smoking and other addictive substances are not suitable for a life according to the will of God. These include, for example, Seventh-day Adventists , The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Jehovah's Witnesses . This attitude is justified, among other things, with instructions from the Bible , for example 1 Corinthians 3, 16 + 17: Do you not know that you are God's temple and that the Spirit of God dwells in you? If anyone corrupts the temple of God, God will destroy him; for the temple of God is holy, and it is you. (Quoted from the Schlachter Bible , edition 2000) The Bible and the church fathers who had drafted the Christian ethics did not even know tobacco smoking.

Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan (1838–1933) spoke out against smoking as early as the beginning of the 20th century. He described smoking as a health hazard and a waste of time. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (1895–1986) believed that the Halacha permitted smoking; nevertheless he said it was not advisable. However, Feinstein completely refused to smoke inside buildings because it also harms the health of bystanders. Rabbi Solomon Bennett Freehof also spoke out against smoking.

In Islam, smoking is predominantly rated as prohibited or at least undesirable . This is justified with the harmful effects of smoking. Deliberately harming your own health is not allowed.

Reasons for tobacco use

Sociodynamic and sociobiological causes

The leading scholars in the field of tobacco research believe that a person's social context and attitudes towards smoking are the most important factors in the development of tobacco addiction.

Anyone who has belonged to a social group in which most of the members smoke for a long time (for example, in the family , in a shared apartment or in a clique ), is at higher risk of becoming a smoker themselves. Also, partnerships between two people in which both smoke only occasionally, may lead to an increase in smoking, because there are more opportunities in a partnership to smoke together.

As a further reason for tobacco consumption, the researchers state that in large parts of the public perception, positive properties such as promoting communication and relaxation are associated with smoking. Tobacco advertising in particular has this view.

Smoking was also interpreted as a cultural adaptation to behavior developed through phylogenetic history: based on Charles Darwin's theory of sexual selection , the zoologist couple Zahavi developed the theory of the handicap principle in the 1970s . According to this, in some species, especially male organisms showed wasteful or self-damaging behavior in order to demonstrate their robustness as partner recruitment to female representatives. Since burned tobacco, like smoke from other ignited organic substances, is initially automatically perceived as having a bad smell and causes physiological defensive reactions such as coughing and nausea, it can be assumed that the tobacco consumer and his environment are implicitly aware of the harmfulness of smoke. The higher smoking rate and other risky behavior of men and male adolescents after puberty (e.g. motorcycling, excessive alcohol consumption , S-Bahn surfing , propensity for violence) therefore suggested that tobacco consumption was a Zahavian handicap.

Effects perceived as pleasant by smokers

Although addictive behavior makes up a large proportion of smoking habits in most smokers, there are social and sociodynamic reasons for smoking as well as other aspects that many smokers find pleasant.

The effect of nicotine, also in combination with caffeine , in the morning or after long tiring activities, is described by smokers as stimulating. People with sleep disorders and chronically shifted internal clocks (so-called night owls ) are particularly susceptible to this behavior pattern in the morning. Of course, the stimulating measures during the day also hinder the next night's sleep, so that it is difficult for those affected to break out of this cycle.

Another aspect is making time for yourself. A “cigarette break ”, provided it is allowed to workers who smoke, serves as a time for relaxation and social communication, during which time a few minutes away from work and stress is gained. Smoking lowers the appetite threshold . It therefore has a specific dampening effect on eating behavior. This is what smokers describe as pleasant or helpful in the fight against actual or supposed obesity .

Young people in particular perceive the social impact of smoking as a positive stimulus. Adolescents and adolescents who spend a long time in a smoking environment (e.g. in the company of smoking parents and colleagues) are very susceptible to this subjectively felt effect. The feeling of belonging that this creates is presented by many, especially young smokers, as a pleasant effect. The feeling of well-being among adolescents who smoke in the presence of others is reinforced by the fact that there is a general smoking ban for children and adolescents only, which means that smoking is perceived as an attribute of adulthood. Anyone who smokes as a young person creates an “adult status”.

Nicotine addiction

Nicotine is partly responsible for the dependence on tobacco products . Comparisons of animal studies and studies of human drug use show that pure nicotine is only slightly addictive, while tobacco cigarette smoke is very addictive. In combination with other substances in tobacco smoke, nicotine has an extremely high potential for dependence and can very quickly lead to dependent behavior . According to David Nutt, the addiction potential of tobacco smoke is somewhere between alcohol and cocaine, with the physical addiction potential corresponding to that of alcohol or barbiturates and the psychological addiction potential that of cocaine.

When smoking, the nicotine contained in the cigarette is released, of which up to 95% is available in the body ( bioavailability ). Some of the nicotine absorbed reaches the brain within 10 to 20 seconds, where it acts on the so-called nicotinergic acetylcholine receptors and triggers a series of physiological reactions, in the course of which the release of certain messenger substances is activated. In addition to the direct effect on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, the high addictive potential of tobacco smoke is primarily attributed to influencing the dopamine system, in particular the reward center of the brain, the nucleus accumbens . The reward effect of smoking is largely mediated by dopamine , so that it interprets the intake as an immediately existentially necessary action.

Above all, it is important that nicotine, in conjunction with other substances in tobacco smoke, subliminally creates the desire for a tobacco product and that the increasingly shorter habit-related stimulus-response interval creates an increasingly pronounced dependency in the form of increased tobacco consumption. Possible withdrawal symptoms can include irritability, restlessness, circulatory problems, headaches and sweating. However, the symptoms go away in 5-30 days.

Today we know that after three weeks of abstinence there is no longer any measurable change in the acetylcholine receptors - that is, they have returned to normal. During this time there can be restlessness and irritability up to aggressiveness and depression. At this point in time, the nicotine itself is no longer detectable in the brain (up to a maximum of three days after the end of nicotine consumption).

As a result, it can be stated that during withdrawal the dependence on the effects produced by tobacco smoke is less important, as shown by many failed therapies with nicotine substitutes, but rather the learning process induced by the nicotinic stimulation of the nucleus accumbens. In a suitable way, this learning process can only be influenced or reversed by strong self-motivation or professional behavioral therapies. Nicotine replacement supplements and other medications can help with withdrawal.

The psychological dependency due to imprinted behavior patterns that develop in the course of a “smoking career” can still be present years after physical withdrawal.

The likelihood of relapse among smokers who quit tobacco without aids is 97% within six months of quitting. Until 2012, it was assumed that nicotine replacement preparations with the correct dosage and further professional guidance could increase the chances of success by 3%. A recent study from 2012 found that relapse rates among those who used nicotine replacement supplements to quit were just as high as those who quit without aids.

Additives

The substances such as ammonium salts and menthol , some of which are added to the tobacco by the manufacturers, accelerate the build-up of nicotine in the blood. The thesis that the addition of ammonium compounds to cigarette tobacco increases the absorption of nicotine from smoke contradicts a scientific study from autumn 2011. It was carried out by a state research institute in the Netherlands and showed that the ammonium content in tobacco has no influence on the Has nicotine intake. Menthol dampens the urge to cough and numbs the painful airways. Sugars and cocoa take the edge off the smoke, making it easier to inhale. Medical organizations are of the opinion that the addition of these substances serves to make it easier for children and young people in particular to start a smoking career. Ammonium compounds (such as ammonium chloride ) are only permitted for snuff and chewing tobacco in Germany, but not for tobacco for smoking.

Health effects

From the middle of the 20th century, the serious health effects of smoking became common knowledge. The health hazards caused by smoking have been proven beyond doubt both epidemiologically and through biochemical-molecular-biological studies. Tobacco smoke contains several thousand substances, many of which are carcinogenic in and of themselves .

The Federal Constitutional Court also found in 1997 that smoking is harmful to health. It was also found superior court that is secured by today's medical knowledge that smoking cancer and heart and vascular diseases caused and causes fatal diseases and health hazards for non-smoking fellow human beings. Tobacco products are luxury goods which, if used as intended, are regularly harmful to health (BVerfG, B. of January 22, 1997, Az. 2 BvR 1915/91, in: BVerfGE 95, 173).

Pollutant absorption

Risk factor for disease

With a time lag of 20 to 30 years, the two curves run largely parallel. Lung cancer was an extremely rare disease at the beginning of the 20th century.

Inhaling tobacco smoke is an established risk factor for the following diseases:

- Different types of cancer, mostly at one or more stations on the route that smoke travels through the body, known colloquially as the smoking street : throat , larynx , esophagus , lung , stomach , kidney , bladder cancer, among others

- Pancreatic cancer and chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

- asthma

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, colloquially "smoker's cough"), emphysema , chronic bronchitis and other lung diseases

- Coronary artery disease and the resulting heart attack

- Peripheral arterial disease , commonly known as smoker's leg called

- stroke

- Erectile dysfunction ( erectile dysfunction )

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Multiple sclerosis , a disease of the central nervous system

- Aneurysms , due to the local bulging of the blood vessels, there is a risk that they will tear and result in internal bleeding

- Cirrhosis of the liver

- Gastrointestinal ulcers

- Cervical carcinoma or cervical cancer, nicotine can be detected in the cervical secretion in three to 35 times the concentration of the serum

- Chronic gum disease (periodontal disease) and other gum diseases

- Weakening of the immune system and the associated increased susceptibility to infectious diseases

- Premature aging of the skin

- Delayed wound healing

- Age-related macular degeneration (the leading cause of blindness in Europe)

- Thrombangitis obliterans , a vascular inflammation known as Winiwarter-Buerger syndrome .

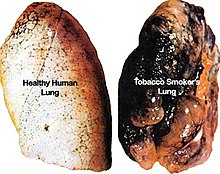

Smoking increases the relative risk of cancer most significantly compared to the general population, followed by gastric and intestinal ulcers, chronic lung diseases and cardiovascular diseases. The increase in risk is particularly evident in lung cancer: more than 85% of lung cancer patients, but - depending on age group, gender and population - only about 25 to 35 percent of the normal population are smokers. Former smokers also remain at an increased risk of lung cancer. Genetic studies have shown that the activity of genes that are responsible for repairing DNA and which could stop the development of lung cancer is permanently reduced in smokers. After a diagnosis of lung cancer is made, the chance of surviving for the next five years is only 16-21%.

Smoking is the strongest risk factor for heart attacks and cardiovascular diseases (98% of all heart attack patients under 40 are smokers). In a meta-study , cardiologists from Northwestern University in Chicago analyzed 18 individual longitudinal studies in which more than 250,000 men and women between the ages of 45 and 75 were followed for at least ten years. One result: just one of the big four risk factors - smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure or cholesterol levels - can increase the normal risk of cardiovascular disease tenfold.

Sudden pain below the hollow of the knee when getting up and walking can indicate diseases of the leg arteries, which can cause toes, later feet and lower legs to die if they become blocked (arteriosclerosis). Pulmonary emphysema (flatulence) allows the patient to exhale with difficulty. The alveoli only partially empty the exhaled air, eventually burst, and due to the reduced oxygen saturation of the blood, the patient can only survive later by breathing abnormally quickly or with the help of oxygen breathing devices.

Furthermore, there is a risk that smoking will adversely affect the course of an existing chronic illness. In multiple sclerosis, for example, the risk of the disability progressing is significantly increased.

The widespread assumption that cigarettes with a reduced nicotine and tar content are less harmful than “normal” cigarettes has now been adequately refuted. It has been shown that the health risk from so-called light cigarettes is just as high as that of cigarettes with a higher tar and nicotine content. For this reason, the use of terms such as “light”, which are misleading for consumers, has been prohibited in the EU since 2003. In addition, a current study shows that smokers of “light cigarettes” find it considerably more difficult to give up tobacco than smokers of cigarettes with a higher tar and nicotine content.

Studies that showed evidence of a possible protection against Alzheimer's disease and other dementias through smoking are now considered refuted. The opposite is the case. In several meta-studies it was found that smokers have a significantly higher risk of dementia from Alzheimer's disease than non-smokers. The risk of vascular dementia and mild cognitive impairment is not or only slightly increased.

Passive smoking, which is usually involuntary, can cause identical symptoms and illnesses. A significantly higher susceptibility to infection can be observed in children of smokers . Nicotine and other metabolic toxins from tobacco smoke can be detected in the hair or in the body and urine even after months.

Smoking and mental health

Smoking is associated not only with physical consequences, but also with mental instability. There are more smokers among patients with mental illness than the average in the population. In a representative British study, there was a higher proportion of smokers among adolescents with a history of suicide than among other adolescents. However, it is unclear to what extent smoking leads to psychological problems or to what extent tobacco consumption is a consequence of existing mental instability.

Change in the human genome

In a 2010 study by the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research in San Antonio , Texas, scientists identified more than 300 genes whose function is changed by smoking. In addition, according to this study, tobacco consumption affects not only individual, but also entire networks of genes. These genes are directly related to the diseases caused by cigarette smoke. The immune system in particular would be negatively affected by the altered gene activity, as many of the genes relevant to the defense against pathogens are impaired in their function. Smoking also favors many processes that are involved in the development of cancer.

Even the amount of tobacco smoke ingested with one or two puffs of cigarettes can cause serious genetic damage.

Scientists led by Ludmil Alexandrov from Los Alamos National Laboratory examined the extent of genetic damage caused by tobacco smoke. They came to the conclusion that the consumption of a pack of cigarettes per day within a year became an average

- 150 additional mutations in each lung cell ,

- 97 additional mutations in each cell of the larynx ,

- 39 additional mutations in each pharynx cell ,

- 23 additional mutations in each cell of the mouth ,

- 18 additional mutations in each bladder cell

- plus six additional mutations in each liver cell .

The greatly increased mutation rate leads to an increased risk of cancer in the affected organs.

Erectile dysfunction (impotence) and infertility

Smoking is one of the main causes of erectile dysfunction - mainly due to its vasoconstricting effect.

In addition, smoking reduces the quality of the sperm , resulting in decreased fertility .

Delayed healing

What has long been established in practice due to the negative effects of tobacco smoke ingredients on the immune system was published in November 2006 for orthopedic injuries, strictly evidence-based, in two control group studies on animals. Bone and ligament injuries heal significantly more slowly when exposed to tobacco smoke (passive smoking) than in those living beings who were not exposed to it. Mice that were regularly exposed to cigarette smoke and had to heal a surgically inflicted fracture had severely reduced levels of type II collagen . The healing was much slower. In another study on healing processes in injuries to the ligamentous apparatus, the animals exposed to tobacco smoke under controlled laboratory conditions proved to be significantly less capable of regeneration. After just one week of the two-month research plan, the mice in the control group had a significantly higher cell density in the wound area. In any case, US statistical analyzes of clinical data show that smokers are more likely to be affected by hip fractures and bone infections and their wound and fracture healing is delayed.

Healing after the use of dental implants is made considerably more difficult by the consumption of nicotine, as this narrows the vessels and the gums are no longer supplied with normal blood. A study with more than 23,300 participants concluded that smokers are 2.5 to 3.6 times more likely to lose their teeth prematurely compared to non-smokers.

radioactivity

Radioactive substances pose a further health risk . They are contained in cigarette smoke because the leaves of the tobacco plant with the trichomes have a structure that filters dust particles containing heavy metals from the air particularly well. These heavy metals also include radioactive ones.

Some of the radioactive nuclides still come from above-ground tests of nuclear weapons in the 1950s / 1960s and satellite crashes in the 1970s. Most of the radioactivity, however, comes from polonium -210, which occurs naturally in the soil in the cultivation regions or which reaches the field through phosphate fertilizers .

Various studies exist on the annual radiation exposure from smoking. There are several studies that indicate effective doses of 0.16 mSv to 1.31 mSv per year with consumption of 30 cigarettes a day . Another study by the American National Council on Radiation Protection & Measurements comes to significantly higher doses, which indicate an average lung dose of 160 mSv / a or an effective equivalent dose of 13 mSv / a for the same consumption.

The annual total radiation exposure in Germany averages 4.05 mSv. Some scientists believe that the radionuclides inhaled through tobacco smoke are responsible for a significant proportion of lung cancer. Polonium is a radioactive α-emitter which can be very damaging to the body of a living organism if it accumulates in the lungs of people who inhale tobacco smoke.

particulate matter

Cigarette smoking creates fine dust , which can reach a high concentration, especially in closed rooms. This was shown by a study by the Dublin Institute of Technology under the direction of Patrick Goodman.

The working group examined the air quality and health of employees in bars and pubs in Dublin seven months before the general smoking ban was introduced in Ireland on March 29, 2004 and exactly one year after. It was found that the fine dust concentration had decreased by 83% during the period. Since this fine dust is considered carcinogenic , it is likely to pose a particular health risk. The concentration of benzene, which is also considered carcinogenic, also fell by 80%. In addition, 81 employees underwent a lung function test, which found that the amount of exhaled carbon monoxide had decreased by an average of 79% in the second test.

When smoking filter cigarettes , the finest dust particles are inhaled from the filter. In a statement by the Federal Institute for Consumer Health Protection and Veterinary Medicine of June 4, 2002, which is no longer available on the web in 2012, it says: "It was described that when cigarettes are smoked with cellulose acetate filters, cellulose acetate fibers containing 'tar' or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are coated, enter the mouth and that such fibers could be detected in the lungs of patients with lung cancer. Ingestion of such fibers has also been considered theoretically. It has also been proven that smoking cigarettes with a filter containing activated carbon released carbon particles. From this the assumption was made that carbon particles coated with tobacco smoke toxins could be inhaled or swallowed when smoking. "

Smoking during pregnancy

According to the German Cancer Society, 30% to 40% of all birth defects and up to 14% of all premature births are caused by smoking during pregnancy. Heavy smokers are also less likely to get pregnant than other women. In Germany, 17.3% of mothers smoked during pregnancy in 2006 - twice as much as in the USA or Sweden.

Smoking during pregnancy endangers the embryo or fetus , as the toxins inhaled by the mother get into the child's organism via the bloodstream. Some carcinogens contained in tobacco smoke can also be detected in the blood of unborn babies, and a higher number of nicotine receptors in the brain makes the development of addiction likely in adolescence at the latest. After intrauterine contact with nicotine, rats also show a stronger tendency to consume nicotine and alcohol as well as a preference for high-fat foods.

Smoking constricts the blood vessels in the placenta and thus affects the child's oxygen supply. Heavy smoking damages the uterus and lowers fertility , because the fertilized egg cell is more difficult to implant in the endometrium . The consequence is an increased risk of miscarriage , malformations ( e.g. cleft lip and palate ), deficiency development and premature birth . The birth weights of babies born to mothers who smoke are on average significantly lower than those of babies whose mothers do not smoke (non-smokers: 11 percent below 2500 grams; up to ten cigarettes per day: 17 percent below 2500 grams; more than 20 cigarettes per day: 25 percent less than 2500 grams). Smoking also increases the risk of children dying later from sudden infant death syndrome or developing leukemia . An increase in the risk of genetic deviations has now also been proven. The rate of malformations increases with cigarette smoking of mother and father above the average. According to recent studies (see links), damage to the chromosomes of the child is also possible through the nicotine consumption of the pregnant woman. Proven is the increased vulnerability of children of smoking mothers for allergy - bronchitis - and asthma , as well as middle ear infections (2 to 3 times more likely than the average). At school age, children from smokers' households are more often overweight and have behavioral problems (poor concentration, inattentiveness, hyperactivity , impulsiveness, aggressive behavior , disorders of spoken language development ). According to the latest studies by American researchers, smoking by the mother or parents during pregnancy even damages the health of their grandchildren.

It now seems to be proven that smoking during pregnancy so significantly reduces the quality of the male offspring's semen that their chances of later having children themselves are significantly reduced. This could also be the reason for the currently obviously falling male fertility: The generation of mothers of now 20 to 40 year olds is the first in which women smoked on a large scale.

brain

A review ( meta-analysis ) from 2013, which included 7 studies with imaging methods and a total of 418 test persons, found evidence of less gray matter in smokers compared to non-smokers in a part of the limbic system , the anterior cingulate gyrus . Whether it is a result of smoking or caused by other factors is unknown.

Lowering life expectancy

Studies show a shortening of the life expectancy of smokers, albeit with different statements about the extent of the shortening.

A study carried out between 1951 and 2001 with over 30,000 British doctors showed that life expectancy for lifelong smokers was reduced by an average of 10 years compared to non-smokers . A Japanese long-term study initiated in 1950 and continued until 2008 with over 67,000 participants came to a similar result. Other studies come to reductions of 5, 7 or 12 years, whereby the reduction is always greater in men than in women.

In a UK study published in 2010, the risk of death increased by 56% over 20 years with little exercise, 52% from smoking, 31% from poor diet and 26% from heavy alcohol.

A study published in 2011 that examined data from 30 European countries concluded that between 40% and 60% of the gender difference in life expectancy was due to smoking tobacco.

Deaths

According to the information provided by the drug commissioner of the federal government and the German headquarters for addiction issues , 110,000 to 140,000 tobacco-related deaths per year can be assumed in Germany, which corresponds to around 12–16% of all deaths. For comparison: in 2009 1,331 drug deaths from illegal intoxicants were registered. The number of deaths from alcohol abuse is estimated at over 70,000, with 74% of these cases being mixed with tobacco.

In 2015 there were 9,535 deaths in Switzerland from direct tobacco consumption (without passive smoking, etc.), which corresponds to 14.1 percent of all deaths. The medical costs alone added up to around three billion Swiss francs that year.

In 2008, around 5.2% of all deaths in Germany were attributed to cancer that was symptomatic of smokers. Lung cancer alone killed 42,319 people. A total of 43,380 people died in Germany in 2008 as a result of cancer that could be attributed to tobacco consumption.

The number of women who died as a result of smoking in Germany has increased over the past ten years from 11,870 in 2005 to 15,748 in 2014.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around a billion people will die from smoking tobacco in the 21st century. Smoking kills around 5.4 million worldwide every year, which, according to Douglas Bettcher of the WHO, is as many deaths as if a jumbo jet crashed every hour. Every year around 600,000 people worldwide die from passive smoking, 165,000 of them children alone, as it is particularly difficult for them to escape the smoke.

Research history

Until the beginning of the 20th century, lung cancer was one of the extremely rare diseases. For example, the proportion of lung cancer in all cancers in 1878 autopsies at the Pathological Institute of the University of Dresden was only 1%. The frequency of this disease increased in the following years. In 1918 lung cancer reached a share of almost 10% and in 1927 over 14% of all cancers. The Handbook of Special Pathology and Therapy noted in the 1930 edition that the number of malignant pulmonary tumors increased at the beginning of the new century and even more so after the First World War. Most of the tumors were observed in men. The survival time between initial diagnosis and death was usually 6 to 24 months, whereby in almost all cases the disease was preceded by longstanding chronic bronchitis. The handbook discussed the possible causes of the increase in lung cancer incidence. Industrial pollution of toxic gases and dust, asphalting of roads, increase in motorized road traffic, exposure to chemical warfare agents during World War I, Spanish flu (1918), and exposure to benzene or gasoline were all considered . Tobacco smoking was only marginally mentioned as a possible cause. It was stated that most studies to date have failed to show a link between smoking and lung cancer. A year earlier, the Dresden doctor Fritz Lickint published a review article ( tobacco and tobacco smoke as an etiological factor in carcinoma ) in which he identified tobacco smoke as a cancer-causing factor. As early as 1923 at a conference of the German Pathological Society, Theodor Fahr was one of the first scientists to suspect that there was a connection between smoking and bronchial carcinoma:

"The stimulus for the development of bronchial cancer comes from m. E. only a chronically acting harmfulness into consideration, hardly a poisoning with war gases, much more the inhalation with cigarette smoking, which undoubtedly has increased. "

The Terry Report provided the first toxicological and therefore scientifically reliable evidence that cigarette smoking leads to a significantly increased incidence of lung tumors (cancer). Larynx, oral cavity, esophagus, bladder and pancreatic tumors can also be caused by tobacco smoke. When the report came out and the harmfulness of inhaled tar condensate to road builders, factory workers and smokers became known, many doctors in the UK gave up smoking. At the same time, from 1953 to 1965, a long-term study of the number of deaths was already running. The result showed that the number of lung cancer-related deaths among men aged 35 to 64 in the UK rose by 7% - that of doctors fell by 38% over the same period. One out of five non-smokers did not reach retirement age - but two of the smokers (cigarette consumption: 25 per day and “on the lungs”). A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in January 2013 states that the likelihood of lifelong smokers reaching the age of 80 is 26% and that of lifelong smokers is 38%, while the likelihood of being 80 years old is. Years of age, 61% for lifelong non-smokers and 70% for non-smokers.

The women who were smokers who were taking birth control pills were also at risk: they were eight times more likely to suffer from strokes, thrombosis or heart attacks. In the case of pregnant smokers, the placenta was also supplied with less blood, so that the fruit of the abdomen contained less nutrients and oxygen. The risk of miscarriage or premature birth became twice as great as that of non-smokers with a daily consumption of 20 cigarettes, and the birth weight of the infants fell by an average of 200 g. The school performance of eleven-year-old children whose mothers had smoked during pregnancy, for example, was on average around three months earlier than that of children who had not been damaged in this way.

In 1986/87, further extensive government reports on the harmfulness of cigarette smoke were submitted in the USA and Great Britain. Accordingly, the risk of developing lung cancer from passive smoking is two to three times as high for the non-smoking partner of smoking spouses as the average risk for non-smokers. Statistically, for every 1,000 young men who smoke, one is murdered. Six of them are killed in traffic accidents, but 250 die from complications and illnesses of smoking. The life expectancy drops by about 15 minutes per cigarette, i.e. In other words, with 20 cigarettes a day, life expectancy is five years shorter, with 40 cigarettes a day, about eight years less.

In the mid-1990s, evidence was finally provided that the benzo [ a ] pyrene in tobacco smoke damaged the tumor suppressor gene p53 . This gene is responsible for the repair of defects in the DNA , which prevents the formation of tumor cells and thus the development of cancer. In addition to research results through statistics and animal experiments, the direct causal relationship between smoking and lung cancer was also proven.

statistics

Share of smokers in Germany

The tobacco atlas of the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) showed a smoking rate of 24.5% for 2013. The rate of ex-smokers was 19.7%. The average age at the start of smoking was 17.8 years (15.4 years in the 15-20 year old age group).

According to the 2017 microcensus , around one in four to five people (22.4%) smoked in the total population aged 15 and over. Less than a fifth (18.8%) smoked regularly .

| Age in years | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 15-18 | 6.3% | 4.8% |

| 18-20 | 21.7% | 14.2% |

| 20-25 | 29.8% | 20.3% |

| 25-30 | 35.1% | 24.3% |

| 30-35 | 36.6% | 24.7% |

| 35-40 | 36.0% | 24.1% |

| 40-45 | 33.2% | 23.4% |

| 45-50 | 32.2% | 24.7% |

| 50-55 | 31.6% | 25.9% |

| 55-60 | 30.2% | 24.9% |

| 60-65 | 25.8% | 20.6% |

| 65-70 | 18.8% | 14.7% |

| 70-75 | 13.8% | 19.8% |

| from 75 | 7.2% | 4.2% |

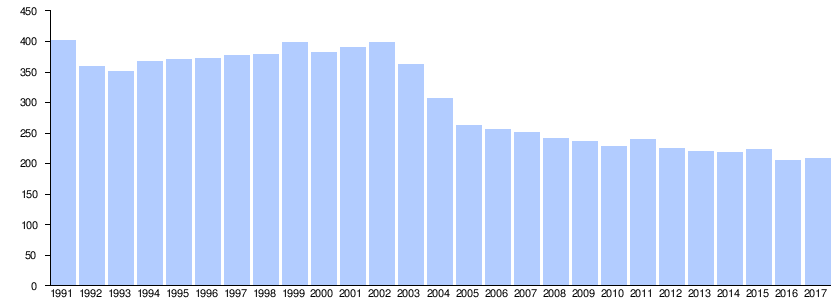

Annual cigarette consumption per inhabitant in Germany

In 2010, around 229 million cigarettes were smoked per day in Germany. That corresponds to around 1,021 cigarettes per inhabitant per year.

| Smoking behavior | Women | Men | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 to 29 | 30 to 44 | 45 to 64 | 65 u. older | total | 18 to 29 | 30 to 44 | 45 to 64 | 65 u. older | total | |

| Daily smokers | 33.6% | 29.3% | 22.0% | 5.1% | 21.9% | 39.3% | 36.0% | 26.1% | 11.8% | 29.2% |

| Casual smoker | 11.0% | 7.4% | 5.3% | 2.4% | 6.1% | 14.4% | 8.3% | 6.9% | 3.8% | 8.1% |

| Ex-smoker | 14.6% | 24.1% | 25.5% | 21.2% | 22.3% | 14.7% | 23.9% | 38.2% | 52.1% | 31.8% |

| Never smokers | 40.8% | 39.2% | 47.2% | 71.3% | 49.7% | 31.5% | 31.8% | 28.8% | 32.4% | 30.9% |

Cigarette consumption per day (Germany)

Number of cigarettes smoked per day (basis: smoker).

| Cigarettes | proportion of |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | 7% |

| 5-9 | 14% |

| 10-14 | 22% |

| 15-19 | 18% |

| 20-24 | 24% |

| 25-29 | 5% |

| 30-34 | 5% |

| 35-39 | 1 % |

| 40 and more | 4% |

Cigarette consumption since 1991 (Germany)

|

Sources: Federal Statistical Office, 1991–2015 and 2017, 2016

The proportion of tobacco in an average finished cigarette can be estimated at 0.7 g . 100 million cigarettes a day correspond to 70 tons of tobacco a day or 25,550 tons of tobacco a year. The value of 220 million cigarettes per day (2013) corresponds to around 56,000 tons of tobacco per year.

Fine-cut tobacco consumption from 2000 to 2013 (Germany)

Average number of fine-cut tobacco sold annually (in tons).

| year | Fine cut in t |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 14,611 |

| 2005 | 33,232 |

| 2010 | 25,486 |

| 2011 | 27,043 |

| 2012 | 26,922 |

| 2013 | 25,734 |

Pipe tobacco consumption from 2000 to 2013 (Germany)

Average number of pipe tobacco sold annually (in tons).

| year | Pipe tobacco in t |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 909 |

| 2005 | 804 |

| 2010 | 756 |

| 2011 | 915 |

| 2012 | 1,029 |

| 2013 | 1,200 |

Proportion of smokers in different countries

The proportion of smokers (daily smokers and occasional smokers combined) in the population (age over 15 years) of the respective countries (figures, unless otherwise stated in the individual records, from 2002 to 2010).

It should be taken into account that in some countries (e.g. India) there is little smoking, but smokeless tobacco is consumed all the more. In other countries, however, including Brazil, harsh laws have actually led to a drastic reduction in tobacco smoking. In other countries, e.g. Indonesia. For example, it should be noted that women rarely smoke there, but men are far more likely to smoke than the following figures indicate.

| country | Proportion of smokers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Measures against smoking

Framework Convention

In 2003, the World Health Organization adopted the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control . The international treaty came into force in 2005 and was signed by 168 contracting parties, including Germany, Austria and the European Union. It is binding for them. The aim is to protect current and future generations from the devastating health, social and environmental consequences of tobacco consumption and passive smoking. To this end, the Convention provides for a number of national, regional and international tobacco control measures, including extensive obligations on production, sale, distribution, advertising, taxation and tobacco-related policies.

Warning notices

EU health ministers have introduced larger and more urgent warnings on cigarette packs and other tobacco product packaging, such as "Smoking can kill", "Smoking causes your skin to age" or "Smoking can lead to a slow and painful death". It is also pointed out that smoking is addictive very quickly and should therefore not even be started. In Germany and Austria, the warning notices contained in Directive 2014/40 / EU are used:

- Smoking causes 9 out of 10 lung cancers

- Smoking causes cancer of the mouth, throat and throat

- Smoking damages your lungs

- Smoking causes heart attacks

- Smoking causes strokes and disabilities

- Smoking clogs your arteries

- Smoking increases the risk of going blind

- Smoking damages teeth and gums

- Smoking can kill your unborn baby

- When you smoke, you harm your children, your family, your friends

- Children of smokers often become smokers themselves

- Quit smoking for your loved ones to go on living

- Smoking decreases your fertility

- Smoking threatens your potency

Information on smoking cessation must also be provided.

In 2004 the EU presented a selection of pictorial warnings that the member states can use. Great Britain, France, Belgium, Spain, Latvia, Hungary and Romania have now introduced the image warnings. In Germany, combined text and image warnings are regulated in Section 14 of the Tobacco Products Ordinance.

Tobacco tax

Another political tool used to curb smoking is the tobacco tax . The general benefit associated with the tax revenue generated must be viewed in relation to the economic damage caused by the health consequences. On World No Tobacco Day 2014, the World Health Organization is calling for an increase in tobacco taxes.

Tobacco Smoking Bans

Since the harmful effects of smoking have been medically proven, there have been appeals to political decision-makers in various countries that the government should counteract smoking. The overriding reasons for such appeals are the request to the state to fulfill a health care obligation towards the citizens, as well as the reference to the economic damage caused by the health consequences .

For its part, the state often finds it difficult to meet such demands because it finds itself in a dilemma that is characterized by conflicting interests: On the one hand, people want to take care of public health, on the other hand, the citizens' personal freedom of choice should not be restricted more than necessary become. There is the view that states are interested in the continued tobacco consumption of their citizens because the tobacco tax is an important source of government income.

The USA is a pioneer in the field of smoking bans , where local ordinances usually stipulate where tobacco smoke is tolerated and where not. Cases are already known here where smoking in public (including on public streets and squares) was generally prohibited in a municipality. In 2003, New York City banned smoking in restaurants. At the same time, extremely high cigarette prices apply here. The Kingdom of Bhutan , located in the Himalayas , was the first country in the world to introduce a nationwide smoking ban in public on December 17, 2004.

Image change

Many states are making efforts to encourage smokers to volunteer to quit. In addition to increasing the tobacco tax, this also includes campaigns and measures designed to give smoking a negative image. For example, the 1989 California Tobacco Control Program aimed to change social norms and make tobacco "less desirable, less acceptable, and less available," which resulted in significant reductions in tobacco use.

Packaging unit ( Plain packaging )

Standardized prohibition sign

To avert fire and health hazards, smoking is now banned in many places. This applies in particular to schools, restaurants, workplaces, petrol stations, clubs (for example at the shooting range of rifle clubs), hospitals, kindergartens, health resorts, shops and forest areas (forest fire).

To mark places where smoking is prohibited , a standardized prohibition sign was developed a long time ago.

Studies by the University of Würzburg show a paradoxical effect of no-smoking signs depicting a cigarette that has just been lit. The results suggest that the desire to smoke is fueled by such stimuli ( craving ). As an alternative, the researchers suggest images of cigarettes as they are smoked.

Advertising ban in the EC

The EC-wide adopted Directive 2003/33 / EC provides for a far-reaching ban on the advertising of tobacco products. Tobacco advertising is generally prohibited in:

- the print media (newspapers and other publications)

- information society services

- all broadcasts.

But sponsorship , for example Formula 1 races, is also affected.

Luxembourg and Germany did not implement this directive into national law until the end of 2006, after all other EC countries. The federal government, both the Kohl and the Schröder governments, had taken action against the advertising ban several times, including in court, in Brussels .

Representation in the media

At the award ceremony of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2015 for “mechanistic studies of DNA repair”, in addition to radioactivity and chemicals, tobacco smoke was mentioned as gene-changing in the sentence explaining the meaning.

Economic aspects

Accounting for damage to health

When accounting for damage to health, the premature death of smokers, lost work due to tobacco consumption, treatment costs for smokers, tobacco taxes, etc. are usually taken into account. Most studies come to the conclusion that tobacco consumption incurs very high costs to society.

Savings

Looking at the health system alone, the Dutch Institute for Public Health and the Environment published a study in 2008 that found that the health system costs of tobacco consumption were offset by the savings from the early demise of smokers. From the age of 20 until their death, smokers caused treatment costs of 220,000 euros, while non-smokers caused 281,000 euros.

Due to the lower life expectancy of smokers, the costs that they are likely to incur for the health care system through expensive treatment of age-related diseases and, above all, where they exist, for long-term care insurance in old age due to an increasing dementia, will decrease. The study “The Health Care Costs of Smoking” says: “If all smokers stopped smoking, the health care costs would be lower at first, but after 15 years they would be higher than they are now.” Other studies, however, come to the opposite conclusion .

The significantly lower longevity risk associated with the reduction in the life expectancy of smokers takes the pressure off the pension system considerably. Financial scientists from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology have calculated savings in the billions based on a purely economic analysis due to the earlier death of smokers. However, the calculation has been described by other economists as unrealistic. Most studies show billions in costs instead of savings.

costs

According to a study by the World Lung Foundation and the American Cancer Society, the global economy is burdened with tobacco consumption due to treatment costs, lost productivity and environmental damage at an annual rate of $ 500 billion.

The University of California has calculated that the US state of California was able to save around 86 billion dollars in the period from 1989 to 2004 through an anti-tobacco program that, among other things, deliberately worsened the image of smoking and thereby significantly reduced tobacco consumption .

A study from Sweden found a difference of 8 to 11 days of illness between smoking and non-smoking workers.

German economy

In 1995, the published Medical Action Group on Smoking and Health e. V. (ÄARG) together with the Non-Smoking Initiative Germany e. V. a calculation that looks at the effects of smoking on the gross national product (GNP). According to this calculation, the losses in 1991 amounted to

- 12.1 billion euros due to incapacity for work ,

- 6.4 billion euros through excess mortality ,

- 23.1 billion euros due to early disability .

(Original figures in DM, here converted into euros)

Due to the burden on the GNP of 41.6 billion euros, tax revenues of 25.3 percent, i.e. 10.5 billion euros, were lost. This contrasted with revenues from tobacco tax amounting to 10 billion euros. The ÄARG therefore comes to the conclusion that the bottom line is that the state does not earn money from smoking. However, the calculation refers to the GNP of the old federal states, while in other tables it also uses data from the new federal states. The calculation can therefore only give a rough estimate.

According to a study from 2008, employees who smoke in Germany are sick more than 2.5 days per year on average than their colleagues who do not smoke, and the costs of secondary diseases burden the economy with 17 billion euros annually. What is not taken into account here is that the difference between the target and actual working hours is greater for smokers than for non-smokers if frequent smoking breaks are not prevented by the employer.

Economic costs also arise from lost life. The assumption of maintenance obligations for the prematurely deceased by the social security systems, in particular long-term payments of widows / widowers and orphans' pensions as well as BAföG benefits, is significant .

Michael Adams, Professor of Business Law, puts the costs at 13 billion euros for smoke-related illnesses and 39 billion euros for reduced life expectancy. Accordingly, a price of 40 euros would actually be required for a pack of cigarettes (see the invoice below).

A study by Stanford University in April 2016 concluded that smoking even affects the prospects of unemployed people to find a new job. Accordingly, even with the same qualifications, smokers are unemployed longer than non-smokers and also earn less after taking up a new job. However, there is no certainty about the exact reasons.

Tobacco production and processing as a source of income and an environmental factor

In Germany, according to statements by the tobacco industry, the cultivation and processing of tobacco as well as the trade in tobacco products generated over € 16 billion in 2009. According to the same source, around 52,000 people are employed in the tobacco industry in Germany, around 42,000 of them in trade and around 10,000 in tobacco processing. The figures for the tobacco industry are rated by the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg as "a statistical artefact". In the entire EU, only 40,000 workers are employed in the cigarette industry, which corresponds to 0.018 percent of the workforce, and not 400,000. The number of people employed in tobacco retail across Europe is at most 150,000 and not 955,358, as the tobacco lobby claims. In Bulgaria , children often worked in the tobacco plantations.

According to a study from 2004, which is based on figures from the Federal Statistical Office , 115,102 jobs were secured in the German wholesale and retail trade in 2002 through the sale of tobacco products.

Mainly due to the cancellation of the European Union subsidies for tobacco growing in 2010, the number of tobacco plantations in Germany fell from 359 (2008) to 200 (2013). Before 2011, the EU temporarily spent up to € 1 billion on promoting tobacco growing. As early as 2009, tobacco growers in Germany only contributed € 7 million to the gross domestic product.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, worldwide sales of tobacco products are estimated at over US $ 740 billion in 2014.

In some of the poorer countries of the world, the tobacco industry is an economic factor that is difficult to replace. For example, the International Tobacco Growers Association warned in 2010: “After implementing the WHO guidelines, some of the poorest countries in Africa that are dependent on tobacco growing will be affected by serious social and economic crises and the loss of jobs to an unprecedented extent. In Malawi alone , 70 percent of workers are directly or indirectly employed in tobacco cultivation. They have no alternative and the WHO cannot offer them one. ”In contrast, the organization Unfairtobacco argues that it is relatively easy to create new job opportunities for workers in tobacco plantations in poorer and emerging countries.

Tobacco cultivation in poorer countries leads to considerable environmental damage there. Who z. B. smokes 20 cigarettes a day, causes the destruction of a tree in the tropical rainforest within two weeks. In addition, tobacco cultivation reduces the usable area for growing food for human consumption.

See also

literature

- Joachim W. Dudenhausen (Ed.): Smoking during pregnancy. Frequency, consequences and prevention . Urban and Vogel publishing house, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-89935-260-3 .

- Christoph Hatschek: Tobacco and the military. A contribution to the history of the blue haze in military circles. In: Viribus Unitis. Annual report 2004 of the Army History Museum. Vienna 2005, pp. 37–50.

- Knut-Olaf Haustein: Tobacco addiction. Health damage from smoking. Causes - consequences - treatment options - consequences for politics and society . Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag, Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-7691-0390-4 .

- Walter Krämer , Gerald Mackenthun: The panic makers. 3. Edition. Piper Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-492-04355-0 . (with numerous evaluations of statistical calculations on life risks, many on the topic of smoking)

- David Krogh: Smoking. Addiction and passion . Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 1993, ISBN 3-86025-189-9 , (on psychological and physiological reasons for nicotine consumption)

- Imre von der Heydt: Do you smoke? Defense of a passion . Dumont, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-8321-7931-3 . (Smoking in the context of cultural history and social criticism )

- S3 guideline tobacco use, harmful and dependent: Screening, diagnosis and treatment of the German Society for Addiction Research and Addiction Therapy (DC addiction). In: AWMF online (as of 2014)

Web links

- Information from the Federal Center for Health Education :

- for adults (including online exit program)

- for young people (including online exit program)

- Passive smoking - a high risk for children

- Database of additives in tobacco products on the website of the Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture , accessed on September 12, 2014

- Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco (PDF; 0.7 MB). Detailed survey results, Eurobarometer Spezial 239, published by the European Commission , January 2006

- Tobacco free. A step-by-step program for smoking advice and therapy in the doctor's office. (PDF; 0.3 MB). Publisher: German Medical Association in cooperation with the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians . 3. revised Edition 2001, 52 pages.

- Tobacco Atlas Germany 2015 (PDF; 46 MB), German Cancer Research Center, 164 pages.

- Stop the tobacco epidemic. Governments and economic aspects of tobacco control (PDF; 0.8 MB). World Bank / German Cancer Research Center. 1999. 156 pages

- Warning notices on cigarette packets - list and background information on the website raucherportal.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ Smoking costs one trillion dollars a year in the global economy . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ↑ K.-O. Haustein, D. Groneberg: Tobacco addiction. Springer Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-73308-9 , pp. 2ff. limited preview in Google Book search

- ↑ Karl Pawek: Smoker, hear the signals . In: Die Zeit , No. 39/1997.

- ^ RN Proctor: The Nazi was on cancer. Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-00196-0 , pp. 271ff. limited preview in Google Book search

- ^ Dominic Hughes: Smoking and health 50 years on from landmark report. In: BBC News. July 5, 2013, accessed July 6, 2013 .

- ↑ tobacco and poverty A VICIOUS CIRCLE. (PDF; 803 kB) WHO, 2004, p. 4; Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ Smoking through the ages. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt , May 2011; accessed on January 6, 2014.

- ↑ a b c Smoking and Social Inequality - Consequences for Tobacco Control Policy (PDF; 51 kB) German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), factsheet from 2004; Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Federal Center for Health Education: The Drug Affinity of Adolescents in the Federal Republic of Germany 2015 - Central Study Results (PDF) 2016, accessed on April 7, 2016.

- ↑ Microcensus 2005: three quarters of Germans are non-smokers. June 22, 2006, Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Claus Hecking: Smoking kills - especially a part of our society. In: Spiegel online. April 6, 2018, accessed April 8, 2018 .

- ↑ Daniel Kotz, Melanie Böckmann, Sabrina Kastaun: Use of tobacco and e-cigarettes as well as methods for smoking cessation in Germany . In: Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online . tape 115 , no. 14 , 2018, p. 235–242 , doi : 10.3238 / arztebl.2018.0235 (original title: The Use of Tobacco, E-Cigarettes, and Methods to Quit Smoking in Germany .).

- ↑ Contributions to health reporting Federal Health Survey: Social differences in smoking behavior and in passive smoke exposure in Germany (carried out, among other things, on the basis of data from the 1998 Federal Health Survey), p. 15 and p. 26. (PDF) Robert Koch Institute , Berlin 2006; Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ↑ Parvin Sadigh: poor smokers in the offside . In: The time. June 29, 2010, accessed September 7, 2014.

- ↑ Boris Orth: The Drug Affinity of Young People in the Federal Republic of Germany 2015. (PDF) BZgA , April 2016, accessed on August 11, 2018 .

- ↑ a b C. Currie et al. a. (Ed.): Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. (PDF; 46.2 MB). (= Health Policy for Children and Adolescents. No. 6). WHO Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen 2012, pp. 141–149., Accessed November 2, 2012.

- ^ BDTA information ( Memento of November 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Dispute over the ban on cigarette machines .

- ↑ Great Britain abolishes cigarette machines .

- ^ T. Raupach et al. a .: Medical students lack bacic knowledge about smoking: Findings from two European medical schools. In: Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 11, 2009, pp. 92-98, PMID 19246446 .

- ↑ With children on board: Austria prohibits smoking in the car. In: Spiegel online . April 5, 2018, accessed April 9, 2018 .

- ↑ Divieto di fumare in auto: normativa vigente e sanzioni previste. In: newsmondo.it. January 30, 2019, accessed September 9, 2019 (Italian).

- ↑ Fumare in auto con dei bambini a bordo è vietato: 110 euros di multa a Trieste. In: tgcom24.it. August 21, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Health risk of passive smoking . German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ); Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ↑ U. Helmert, P. Lang, B. Cuelenaere: Smoking behavior of pregnant women and mothers with small children. In: Social and Preventive Medicine. 43, 1998, pp. 51-58. PMID 9615943 .

- ↑ Amotz Zahavi, Avishag Zahavi: Signals of Understanding. The handicap principle. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-458-16927-X .

- ↑ Geoffrey Miller: Sexual Evolution, Choice of Partner, and the Origin of Mind. Heidelberg 2001, ISBN 3-8274-1097-5 .

- ↑ Why owls become smokers. at: heise.de , as of March 30, 2006, accessed on February 13, 2012.

- ↑ No smoking room or smoking breaks for employees of the city of Cologne. ( Memento of September 14, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) on : arbeitsrecht.de , 2010.

- ^ Dieter Henkel: Addiction and social situation. What are the risks for which groups of children and adolescents? (PDF) Lower Saxony Addiction Conference, October 18, 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Karl Fagerström: Determinants of Tobacco Use and Renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence . In: Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 14, 2012, pp. 75-78 July 2013.

- ^ Anne-Sophie Villégier, Lucas Salomon, Sylvie Granon, Jean-Pierre Changeux, James D Belluzzi, Frances M Leslie, Jean-Pol Tassin: Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors Allow Locomotor and Rewarding Responses to Nicotine . In: Neuropsychopharmacology . 31, 2006, pp. 1704-1713.

- ↑ James D Belluzzi, Ruihua Wang, Frances M Leslie: Enhances Acquisition of Nicotine Self-Administration in Adolescent Rats . In: Neuropsychopharmacology. 30, 2005, pp. 705-712.

- ^ JE Rose, WA Corrigall: Nicotine self-administration in animals and humans: similarities and differences. In: Psychopharmacology . 130, 1997, pp. 28-40. PMID 9089846 .

- ↑ SCENIHR : Questions about tobacco additives: Is the development of nicotine addiction dose-dependent?, (2010), accessed July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Surgeon General (US): How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General, Nicotine Addiction: Past and Present, (2010), accessed July 29, 2013.

- ↑ David Nutt, Leslie A King, William Saulsbury, Colin Blakemore: Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. (PDF). In: The Lancet . 369, 2007, pp. 1047-1053.

- ↑ J. Le Houezec: Role of nicotine pharmacokinetics in nicotine addiction and nicotine replacement therapy: a review. In: The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 7, 2003, pp. 811-819. PMID 12971663 .

- ↑ LF Stead u. a .: Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation . Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group, July 16, 2008.

- ↑ DKFZ nicotine replacement and other drugs for smoking cessation . Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ HR Alpert, GN Connolly, L. Biener: A prospective cohort study challenging the effectiveness of population-based medical intervention for smoking cessation . In: Tobacco Control. 22, 2013, pp. 32-37. PMID 22234781 .

- ↑ Jan van Amsterdam, Annemarie Sleijffers, Paul van Spiegel, Roos Blom, Maarten Witte, Jan van de Kassteele, Marco Blokland, Peter Steerenberg, Antoon Opperhuizen: Effect of ammonia in cigarette tobacco on nicotine absorption in human smokers . In: Food and Chemical Toxicology . 49, 2011, pp. 3025-3030.

- ^ Ralf Schwarzer: Psychology of health behavior. Hogrefe Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-8409-1816-2 , p. 309. ( limited preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Smoking as a risk of diabetes. In: Ärzteblatt. December 12, 2007 aerzteblatt.de. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on May 4, 2012 ; Retrieved August 25, 2012 .

- ^ Cancer in Germany - Lungs. (PDF) Robert Koch Institute , December 17, 2015, accessed on February 3, 2016 .

- ↑ Berry et al. a .: Lifetime Risks of Cardiovascular Disease. In: N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2012, pp. 321-329. PMID 22276822 .

- ↑ The content of the specialist article in German in 2012 from January 2012.

- ↑ P. Sundström, L. Nyström: Smoking words the prognosis in multiple sclerosis. In: Multiple sclerosis. 2008, Volume 14, pp. 1031-1035. PMID 18632778 .

- ↑ JE Harris et al. a .: Cigarette tar yields in relation to mortality from lung cancer in the cancer prevention study II prospective cohort, 1982-8. In: BMJ. 328, 2004, p. 72. PMID 14715602 .

- ^ R. Peters, R. Poulter, J. Warner, N. Beckett, L. Burch, C. Bulpitt: Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review. In: BMC geriatrics. Volume 8, 2008, p. 36, ISSN 1471-2318 . doi: 10.1186 / 1471-2318-8-36 . PMID 19105840 . PMC 2642819 (free full text).

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Smoking Among Adults With Mental Illness. 2013. (Download April 24, 2014).

- ↑ C. Donath, E. Gräßel, D. Baier, S. Bleich, T. Hillemacher: Is parenting style a predictor of suicide attempts in a representative sample of adolescents? (PDF) BMC Pediatrics. 14, 2014, p. 113.

- ↑ Tobacco consumption disrupts the activity of important genes. In: Spiegel online. July 15, 2010, accessed July 24, 2010 . , The Original Article: Jac C Charlesworth: Transcriptomic epidemiology of smoking: the effect of smoking on gene expression in lymphocytes. In: BMC Medical Genomics. 3, 2010, p. 29. PMID 20633249 .

- ↑ What cigarettes do to DNA. In: Wissenschaft.de. April 2, 2004, accessed July 22, 2019 .

- ↑ How tobacco smoke damages the genetic makeup. In: Wissenschaft.de. November 4, 2016, accessed July 22, 2019 .

- ↑ M. Kendirci et al. a .: The impact of vascular risk factors on erectile function. In: Drugs Today (Barc). 41, 2005, pp. 65-74. PMID 15753970 , doi: 10.1358 / dot.2005.41.1.875779 .

- ↑ JY Jeremy, DP Mikhailidis: Cigarette smoking and erectile dysfunction. In: JR Soc Promot Health. 118, 1998, pp. 151-155. PMID 10076652 .

- ↑ a b I. Peate: The effects of smoking on the reproductive health of men. In: Br J Nurs. 14, 2005, pp. 362-366. PMID 15924009 (Review)

- ↑ SG Korenman: Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction. In: Endocrine. 23, 2004, pp. 87-91. PMID 15146084 , doi: 10.1385 / ENDO: 23: 2-3: 087 .

- ^ G. Dorey: Is smoking a cause of erectile dysfunction? A literature review. In: Br J Nurs. 25, 2001, pp. 455-465. PMID 12070390 .

- ^ A. Ledda: Cigarette smoking, hypertension and erectile dysfunction. In: Curr Med Res Opin. 16, 2000, pp. S13-s16. PMID 11329815 .

- ↑ B. Hossam et al. a .: Smoking delays chondrogenesis in a mouse model of closed tibial fracture healing. In: J Orthop Res. 24, 2006, pp. 2150-2158. doi: 10.1002 / jor.20263 . PMID 17013832 .

- ↑ Study: Smoking increases the risk of tooth loss. T-online, September 15, 2015, accessed September 15, 2015 .

- ^ Cigarettes: Tobacco is radioactive (Medizinauskunft.de) As of June 21, 2007.

- ↑ Radiation Protection Commission: Radiation protection considerations with regard to the crash of nuclear-powered satellites. (PDF) December 6, 1989, accessed August 25, 2012.

- ↑ Skwarzec u. a .: Inhalation of 210Po and 210Pb from cigarette smoking in Poland. In: J Environ Radioact. 2001, Volume 57, pp. 221-230. PMID 11720371

- ↑ C. Papastefanou: Radiation dose from cigarette tobacco . In: Radiation Protection Dosimetry . tape 123 , no. 1 , 2006, p. 68-73 , doi : 10.1093 / rpd / ncl033 .

- ^ Römpp-Lexikon Chemie AZ, e-book edition . Version 2.0, 10th edition. Thieme, 1999 (from the entry on tobacco smoke).

- ^ Radiation Exposure of the US Population from Consumer Products and Miscellaneous Sources . In: National Council on Radiation Protection & Measurements (Ed.): NCRP Report . tape 95 , 1987. Radiation Exposure of the US Population from Consumer Products and Miscellaneous Sources ( Memento November 12, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ www.rauchstoppzentrum.ch: Radiation exposure through smoking. without date of publication, accessed June 25, 2010.

- ↑ P. Goodman et al. a .: Effects of the Irish Smoking Ban on Respiratory Health of Bar Workers and Air Quality in Dublin Pubs. In: American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 175, 2007, pp. 840-845. PMID 17204724 .

- ↑ a b Too many young women smoke during pregnancy. ( Memento of June 24, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Obstetricians and gynecologists online, July 15, 2008.

- ↑ Direct damage. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. January 4, 2007, p. 18, accessed February 17, 2012.

- ↑ G.-Q. Chang, O. Karatayev, SF Leibowitz: Prenatal Exposure to Nicotine Stimulates Neurogenesis of Orexigenic Peptide-Expressing Neurons in Hypothalamus and Amygdala. In: Journal of Neuroscience. 33, 2013, pp. 13600-13611, doi: 10.1523 / JNEUROSCI.5835-12.2013 .

- ↑ a Danish doctoral thesis and this publication emerged from the thesis .