Passive smoking

Passive smoking is the inhalation of tobacco smoke from the room air . Both animal experiments and epidemiological studies indicate that passive smoking poses a health risk , albeit to a lesser extent than active smoking . This applies in particular to those passive smokers who are permanently exposed to the pollutant. Since it is not possible to protect against inhalation of tobacco smoke in certain places, it is a hot topic of public discussion. Unintentional ingestion of smoke is often perceived as annoying by non-smokers and viewed as a nuisance, which is why they advocate measures to protect non-smokers .

Aspects of secondhand smoke

General introduction

Passive smoke arises from sidestream smoke and exhaled mainstream smoke. While using a cigarette, the main stream smoke is generated during the smoker's puff, and the temperature in the embers rises. During the pauses between smoking, the cigarette continues to glow at a lower temperature and releases the sidestream smoke. It is estimated that more than 55% of tobacco burns to sidestream smoke. According to other data, the volume ratio of sidestream smoke to mainstream smoke when smoking cigarettes is 4: 1.

The sidestream smoke released into the room air by smoldering cigarettes is absorbed by the people present through their breathing. This also happens when you inhale pipe and cigar smoke. According to a study by Stanford University from 2007, pollution levels in the open air are not negligible: In the vicinity of a smoker outside closed rooms, the exposure is brief, but hardly less intense than in closed rooms.

Chemical composition

Tobacco smoke is made up of a mixture of gaseous substances and particles . The analysis can identify up to 9,600 different chemical compounds in varying proportions. According to a publication by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) of the World Health Organization (WHO), a total of 69 chemical compounds classified as carcinogenic had been identified in tobacco smoke by the year 2000.

The composition of sidestream smoke was examined in various studies, but only one study compared sidestream smoke with mainstream smoke (Massachusetts Benchmark Study from 1999, cited in IARC Monograph 83, p. 1200): According to this, there were substances that were found in sidestream smoke in higher concentrations than in mainstream smoke, such as B. ammonia (147x), pyridine (16.1x), formaldehyde (14.8x), quinoline (12.1x) and 3-aminobiphenyl (10.8x). Other substances had equally high concentrations in side and mainstream smoke, such as B. benzene (1.07x), acrylonitrile (1.27x), mercury (1.09x) and hydrocyanic acid (0.77x). The tobacco-specific nitrosamines had slightly lower values in sidestream smoke (0.25 to 0.55). Lead was practically only detectable in mainstream smoke (0.09 ×). Pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons , N- nitrosamines , aromatic amines , benzene, vinyl chloride , arsenic , cadmium , chromium , dry condensate ( tar ) and the radioactive isotope polonium 210 are carcinogenic .

Tobacco smoke and secondhand tobacco smoke have been classified as group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization (WHO) . These are substances that can cause cancer in humans and which can be assumed to make a significant contribution to the risk of cancer. Other examples of substances that can cause cancer in humans are asbestos , benzene, benzopyrene , 1,3-butadiene , formaldehyde and vinyl chloride.

According to the criteria of the German Ordinance on Hazardous Substances, the relevant Technical Rule for Hazardous Substances 905 (TRGS 905) classifies passive smoking as a development-damaging category 1.

In addition to the carcinogenic components, passive smoke also contains acutely toxic substances such as hydrogen cyanide and ammonia , the nerve toxin nicotine and the breath toxin carbon monoxide .

The sharp fine dust formed from the irritant particles , which penetrates deep into the lungs and transports radioactive gases and heavy metals with it, is of particular importance . The diameter of the particles in the mainstream smoke is around 0.4 µm, the sidestream smoke consists of finer particles of around 0.2 µm (Scherer and Adlkofer 1999). The particles therefore not only reach the bronchial tree, but also the alveoli . The pulmonary epithelium becomes inflamed .

Details on the percentage of cancer deaths as a result of carcinogenic substances in the natural environment (air, water, food, etc.) can be found in the article Cancer - Theories on Cancer Triggers .

Electric cigarettes

With e-cigarettes, is produced unlike the tobacco cigarette, no harmful side-stream smoke . Since a consumer of electronic cigarettes exhales some parts of the vaporized liquid again after inhaling, scientific studies assume that there is such a thing as passive vapor.

Studies published in 2012 showed that the effects of the investigated passive steam on the indoor air, when compared with traditional tobacco smoking, are hardly measurable. In addition, the passive vapor does not have the toxic and carcinogenic properties of tobacco cigarette smoke. The researchers identify the lack of combustion and the lack of sidestream smoke in the case of the electronic cigarette as reasons for the measured differences in air pollution. The researchers conclude that “on the basis of ARPA data on urban air pollution, it can be said that breathing in a large city can be less healthy than being in the same room with an e-cigarette user. "

In a study published in October 2012, in which passive steam was subjected to a risk analysis, it turned out that there are no significant risks to human health. In addition, during the cancer risk analysis carried out, the researchers found that none of the samples examined had exceeded the risk limits for children or adults.

Also in October 2012, a study by the former researcher for the World Health Organization, Andreas Flouris, was published, which examined the effects of passive steam on the human body. He came to the conclusion that the steam had no effect on the blood values of third parties. The author also stated that when tobacco smokers use the e-cigarette, this also had no effect on the blood values examined. In contrast, according to Study active and passive tobacco smoke leads to an increased number of leukocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes.

According to an independent safety report by New Zealand tobacco control researcher Murray Laugesen, the exhaled vapor of an e-cigarette user is not harmful to third parties because it contains almost no nicotine and no combustion products.

Spread in premises

When there is a draft, passive smoke spreads in the room depending on the flow conditions. Without a draft there is a uniform spread according to the laws of diffusion or Brownian molecular motion . The individual particles behave like a gas-like aerosol . The diffusion gradient of the tobacco smoke source in the room itself is decisive.

The parameters of the spread are:

- Size and geometry of the room

- Room temperature including temperature gradient

- Air exchange

- relative humidity

- mixing (air exchange)

- Air flow at head level

- Desorption and sorption of the surfaces

- possibly existing air purification systems

According to a study by the DKFZ , measurements of respirable particles in the room air showed that in restaurants with smoking rooms the pollutant load is measurably increased even in non-smoking areas, since the smoke from the smoking room penetrates into the adjacent rooms. The harmful substances in tobacco smoke (e.g. benzene or formaldehyde ) are also introduced into rooms by smokers after smoking outdoors, as the substances stick to skin, hair and clothing, from where they are released into the room over time and pollute the room air like passive smoking. This is also the reason why smokers smell like smoke.

proof

Cotinine is used as an exposure marker for secondhand smoke . Cotinine is a breakdown product of nicotine and is also found in the blood and urine of passive smokers. It has a half-life of 16 to 22 hours.

Typical cotinine values:

- in smokers 1000-2500 ng / ml

- Non-smokers:

- not exposed to secondhand smoke: 1.7 ng / ml

- Exposure to secondhand smoke: 2.6 ng / ml

- Restaurant staff: up to 5.6 ng / ml

- Discotheque staff: up to 24 ng / ml

- Personnel in bars: up to 45 ng / ml

Measurements of passive smoke exposure by determining the cotinine level in the blood are, however, subject to certain sources of error - the consumption of certain types of vegetables also increases the cotinine level, so that this method is not necessarily suitable for accurately assessing the risk of passive smokers for certain diseases.

Some studies have determined previously individual parameters of tobacco smoke, they dealt mainly with the usual volatile organic compounds ( volatile organic compound , VOC), the nicotine and other tobacco-typical substances such as aldehydes.

Health hazards

The pollutant passive smoke acutely irritates the airways ( asthma attacks , bronchitis , inflammation of the deep airways). Passive smoke can lead to shortness of breath during physical exertion, increased susceptibility to infections , headaches and dizziness, even with short exposure . Secondhand smoke can contribute to heart disease, angina , heart attack , stroke , lung disease, and chronic respiratory disease. Various substances in tobacco smoke cause the blood to clump together and clog the coronary arteries and cerebral vessels.

Experiments with rats demonstrated the mutagenic (gene-changing) effects of passive smoking. The rats were exposed to sidestream smoke (smoke machine 2-4 filter cigarettes) over a period of several days. Research did not find any limit values for carcinogenic substances in tobacco smoke below which no health risk is to be expected. That is why even the smallest exposure carries the risk of developing tumors such as bronchial carcinoma . Many epidemiological studies have found an increased relative risk of lung cancer after passive smoking at home or at work. It is particularly important that the relative risks are greatest in the groups with the highest exposure and that there is an exposure-effect relationship.

In contrast to many poisons, in which the body can neutralize certain maximum amounts without harm, no mechanism is known for carcinogenic substances that could completely exclude the potential hazard below a specific concentration. See also carcinogenesis .

Particularly at risk are unborn children, infants and toddlers, as well as people with health problems or susceptibility and the chronically ill (e.g. asthmatics ).

Epidemiological Considerations

From an epidemiological point of view, it is problematic to clarify the direct relationships between effect and cause. For example, bronchial carcinoma has latency periods of up to ten years , depending on the exposure of the patient . According to this, it is very difficult to prove a single cause, such as exposure to secondhand smoke, in individual cases. Rather, statistical investigations with large numbers of test persons are required . In fact, a number of studies have shown an increased risk of certain diseases (such as lung cancer, coronary heart disease, COPD ). Two extensive studies, on the other hand, did not find any evidence of a statistically significant increase in risk with regard to cancer and heart disease or cancer, which, however, does not destroy the results of the studies with significant increases in risk. One difficulty with epidemiological and statistical studies is to clearly differentiate the health risk of passive smoking from so-called “ lifestyle factors ”. For this purpose, such factors must either be checked with special statistical methods ( partial correlation , methods of multiple regression analysis , loglinear models , etc.). Or so-called “ statistical twins ” (see also matched pair technique ) must be found that match in as many other features as possible. With such methods, of course, only those influencing factors can be hidden that were actually recorded in the study. One consequence of this is that a study becomes less meaningful if relevant characteristics are not recorded as variables. These considerations were z. B. employed by the American health authorities when they presented their evaluation in 2006 and found that secondhand smoke increased the risk of these diseases.

parameter

The risk of coronary artery disease in the workplace increases dramatically for non-smokers with the factors involved: number of cigarettes smoked, number of smokers and duration of exposure (AJ Wells, 1998).

General damage

A study in Puerto Rico found that secondhand smoke was associated with low levels of vitamin C in the blood. A deficiency in vitamin C can be particularly damaging for children as their bodies are still growing. Di Franza et Lew pointed out in Pediatrics in 1996 that the risk of respiratory diseases ( otitis media , pneumonia , bronchial asthma) in children of smokers is 1.5%.

Passive smoking increases the risk of suffering a stroke by 18% for non-smokers, for example, who are regularly exposed to passive smoke in their own home.

The Surgeon General's report from June 2006 (page 15) shows that the evidence for a causal relationship between the risk of stroke and secondhand smoke is suggestive but insufficient. Out of a total of 6 studies, only two are statistically significant, one of them just barely.

As scientists from the American Association for Cancer Research reported in October 2010, the risk of breast cancer from passive smoking increases almost three times in postmenopausal women and almost five times in younger women.

The Surgeon General's June 2006 report (page 15) suggests that the evidence for a causal relationship between breast cancer risk and secondhand smoke is suggestive but insufficient. In the further course of the report (Chapter 7) it is stated: "The absence of an established and consistent correlation in epidemiological studies between active smoking and breast cancer weakens the biological plausibility of a possible causal relationship between secondhand smoke and breast cancer."

Unborn and adolescents

According to the DKFZ, almost half of all children in Germany have to smoke passively at home. 40% of passive smokers worldwide are children.

In Germany there are 500 to 600 deaths from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) each year , of which up to half of the cases are attributed to passive smoking. Smoking during pregnancy and after childbirth significantly increases the risk of this. The risk of SIDS with parental tobacco consumption is two to four times higher than in smoke-free households. The Federal Center for Health Education recommends not letting babies sleep in bed with smokers to reduce risk. (See also co-sleeping .)

In a joint study published in 2009 by several German universities, hospitals and institutes, a group of almost 6,000 children up to the age of 10 was able to demonstrate that passive smoking significantly increases the rate of hyperactivity , attention deficits and other behavioral disorders. Both prenatal and postnatal exposure to tobacco smoke were examined. In addition, toddlers aged four to five years suffer from high blood pressure when their parents smoke.

Children from households in which both parents are smokers complain twice as often of coughing, hoarseness, dizziness, headaches and back pain as well as sleep and concentration disorders as children from non-smoking households. In children up to three years of age, parental smoking is associated with a two to three-fold increased risk of otitis media. Passive smoking also delays the growth of the lungs of infants and young children and contributes to reduced lung function.

Passive smoking increases the risk of infection in children by 20% to 50% and can disrupt their mental development because the growing brain reacts much more sensitively than that of adults. An accumulation of brain tumors has even been observed. The “Doctors Against Smoker Injury” initiative equates smoking in the car with “mistreating accompanying children” and sees this as being as dangerous as not wearing seat belts. (See also the ban on smoking in passenger cars .) In addition, according to the initiative, passive smoking in childhood could not only cause damage in childhood, but also long-term effects (e.g. asthma, lung cancer or bladder cancer in adults). It is not enough to go to another room in the apartment to smoke or to open the window. Only completely refraining from smoking in the home could protect children from serious damage to health from passive smoking.

Mortality studies

International

According to a 2010 study by the WHO, around 600,000 people die each year as a result of passive smoking. That corresponds to around every hundredth death worldwide. This first global study on secondhand smoke also came to the conclusion that 165,000 children die annually as a result of unintentional smoking. With the numerous additional diseases caused by passive smoking, this would cost the global economy high double-digit billions.

Germany

According to the 2009 microcensus, 25.7 percent of the population aged 15 and over in Germany smoke. Most smokers are in the age groups between 20 and 50 years of age. The smoking rate among young people has more than halved since the turn of the millennium.

According to a study by the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) from 2005, 35 million adults are exposed to the pollutants of tobacco smoke at work (8.5 million) or in their free time. Around 8 million children and young people under the age of 18 lived in households with at least one smoker. 170,000 infants would be contaminated with secondhand smoke as fetuses in the womb .

As a result, around 3,300 non-smokers and former smokers would die each year from the health effects of passive smoking. This would be 0.3% of all annual deaths in Germany and would exceed the sum of all deaths from asbestos and illegal drugs . Of these approximately 3,300 deaths, 2108 are in people over the age of 75.

The deaths were essentially divided into:

- 2140 deaths from coronary artery disease

- 770 deaths from strokes

- 260 deaths from lung cancer

- 60 deaths caused by nicotine - poisoning

The latter suffered primarily in newborns who are permanently exposed to tobacco smoke in their home environment or whose mother smoked during pregnancy .

Switzerland

The estimate of the years of life lost potentially due to passive smoking (YLL ) was 969 years or 0.3% of the total potential years of life lost . The disease burden caused by passive smoking was estimated at 0.2% of the total disease burden in Switzerland.

United States

The American Lung Association speaks of 3,000 lung cancer deaths and around 35,000 fatal heart diseases in the USA in 2004 that can be traced back to passive smoking.

Prevention

Protection against passive smoking is considered to be the most efficient (cheapest) and most effective (most effective) individual measure in tobacco prevention: It protects the part of the population who does not consume tobacco products, lowers the entry rate among children and adolescents, motivates tobacco users to quit and lets them go at the lowest possible cost implement.

Legal situation

International treaties

In the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control of 21 May 2003 on Tobacco Control (Law on Tobacco Framework Convention FCTC), which was ratified by Germany on 24 October 2003, it is determined that secondhand smoke "to disease, disability and death" leads . The 168 ratifying states undertake, among other things, to protect their citizens from the dangers of secondhand smoke.

According to a WHO study from 2009, more than 94% of humanity worldwide is not protected from tobacco smoke by law.

Germany

When considering the legal situation, it should be noted that protection from passive smoking is not necessarily linked to other tobacco prevention measures (including price, access).

The consumption of tobacco products is considered socially customary in Germany. Smoking is covered by the protection of the fundamental right of general freedom of action . Laws that prohibit or restrict smoking are therefore in need of justification and must comply with the principle of proportionality , i.e. H. have a legitimate purpose, be necessary and appropriate.

The Federal Constitutional Court regards protection against the dangers of passive smoking as a legitimate purpose of the law. When assessing the necessity, however, the legislature has a lot of leeway. In contrast, parts of the literature expressly affirm the state's duty to protect non-smokers on the basis of their right to life and physical integrity. Depending on the situation, the general freedom of action of smokers may therefore be of secondary importance.

Employment Law

In Germany , as in Austria and Switzerland, there is a legal right to a smoke-free workplace. In Germany, Section 5 of the Workplace Ordinance (ArbStättV) has been regulating the protection of employees from passive smoking since October 2002 . The implementation of the non-smoker protection can be restricted for companies with public traffic, where the nature of the company and / or the employment does not allow the employee to avoid contact with tobacco smoke. The basis is the right to physical integrity. The regulation obliges employers to take all necessary measures to protect employees from passive smoking, provided that the type and nature of the company allows this. The choice of means is left to the employer, provided that employees are effectively protected, even if the majority of employees are against these means, such as smoking bans or smoking only in certain rooms.

MAK and BAT classification

As early as 1988, passive smoking was assigned to Category 1 of Section III of the MAK ( Maximum Workplace Concentration ) and BAT ( Biological Substance Tolerance Value) list of values by the German Research Foundation .

In gastronomy

Passive smoke is the greatest indoor air pollution in the catering sector. The German federal government had initially agreed a step-by-step plan with the German Hotel and Restaurant Association , which provided for at least half of the seats in 90% of German restaurants to be made available to non-smokers by March 2008. Companies with more than 40 seats or more than 75 m² guest area were affected. The agreed goals were voluntary, subject to the introduction of a general smoking ban. The Federal Drug Commissioner was responsible . However, the first stages of the plan were not implemented. As a result, the responsible federal states passed comprehensive non-smoking protection laws from 2007 onwards.

Accommodation in a separate side room in restaurants does not lead to any significant improvement (Cains et al., 2004). It is necessary to prevent the transmission of tobacco smoke into adjacent rooms. This can be costly, for example, through closed, separately ventilated rooms and negative pressure in smoking rooms with a direct exhaust system. According to the latest findings from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, the largest health research facility in Germany, ventilation systems only bring about a slight improvement in air quality and are therefore not suitable for protecting non-smokers. The DKFZ writes: "Ventilation systems do not provide effective protection against the pollutants of tobacco smoke, since even the most modern ventilation systems cannot completely remove the dangerous substances in tobacco smoke from the room air."

Nonsmoker protection laws

According to current law, the release of toxic and carcinogenic air pollutant mixtures is fundamentally prohibited in Germany. However, there is a small limit that cannot be reached through the consumption of tobacco products. Affected legal interest is above all the right to life and physical integrity of passive smokers in accordance with Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Basic Law . Extensive non-smoking protection laws have therefore come into force in Germany in recent years.

In the countries

For the areas where the legislative competence of the countries falls, most German states comprehensive measures have taken that ban smoking in public buildings and schools in principle and allow for restaurants only in separate smoking areas, but with one after a ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court necessary Exception for one-room bars. However, the Federal Constitutional Court considers a smoking ban for restaurants without any exception to be constitutionally unobjectionable. In separate votes, this was denied by the judges Bryde and Masing. Masing sees smoking in connection with eating and drinking as a traditional cultural component, which the legislature may push back with regard to the protection of non-smokers, but should not be completely withdrawn from the commercial offer in the public.

Violations of the state's non-smoking protection laws are classified as administrative offenses both by the smoker and z. B. the restaurateur punished with fines.

At the federal level

At the federal level, since the Federal Non -Smoking Protection Act came into force on September 1, 2007, a comprehensive smoking ban has been in effect in all federal office buildings as well as in all public transport and at airports and train stations. In the latter, special smoking areas can be set up on the platform. These are usually identified by yellow markings and signs. Violations are treated as administrative offenses and punished with fines. A general ban on smoking in public spaces, including outside buildings or public transport, is viewed by the federal government as unconstitutional due to the lower risk situation and conflicting legal interests.

Discussions

There is disagreement about what is to be understood by “type and nature” of the company and to which jobs, types of business and activities this applies. The restaurant associations claim, for example, that the type and nature of a restaurant is not suitable to effectively protect employees from passive smoking. Another approach assumes that only those employees, workplaces, activities and companies that have no fixed spatial reference or no authority to issue instructions in their environment fall under this exception. If you follow this point of view, this includes, for example, sales representatives, takeaways, courier services, postmen, etc., since the environment there cannot be subject to the employer's sphere of influence.

More and more voices are being raised who want to align the protection of employees in the hospitality industry with that of other employees. The reasoning is simple: the restaurateur has domiciliary rights and can take simple measures, such as removing ashtrays or attaching no-smoking signs , to ensure that there is no smoking on his premises. The nature of the business, namely the consumption of food and drinks, is not affected. In addition, the majority of German citizens (> 70%) do not smoke, which, although it cannot rule out a negative economic impact, makes it unlikely. This has also been confirmed by numerous studies from countries that already have rules for protection against secondhand smoke, such as Ireland and the USA . It is also argued that the European Social Charter gives every worker within the EU the right to healthy working conditions and that this right is currently being violated.

Numerous studies from countries with strict smoking bans, which refer to the official evaluations of the financial and statistical offices, could not determine any decline in sales in the catering trade. Only in surveys commissioned by the tobacco industry and the restaurant associations is there talk of a serious decline in sales. Internal documents of the tobacco industry, which had to be made public in the course of lawsuits in the United States, show that the restaurant associations have been working with the tobacco industry for a long time and have also accepted sponsorship money from it.

Other countries

A court in Rome / Italy has awarded a woman suffering from lung cancer for passive smoking a sum of 400,000 euros in damages. The court based its decision on the fact that the woman was not adequately protected at her workplace. The lawsuit was directed against the Italian state. The plaintiff was an employee of the Italian Ministry of Education and was exposed to the smoke of her colleagues in a cramped office for seven years. After the woman was diagnosed with lung cancer, part of her right lung had to be removed in 1992. In 2000 the woman died in a traffic accident. However, at the time she was undergoing chemotherapy . The compensation must now be paid to the surviving dependents of the deceased.

A spokesman for the Codacons consumer protection group , which supported the lawsuit, described the judgment as a very important precedent as it paved the way for hundreds, thousands of other cases . The victim complained about the smoke in the office, but the only answer they received was that there was no smoking ban law at the time.

A similar case is the ruling in the case of the Canadian waitress Heather Crowe , who fell ill with lung cancer in 2002 after being exposed to secondhand smoke as a waitress for 40 years without ever having smoked. Heather Crowe successfully sued the Workplace Safety & Insurance Board for damages, which initially did not admit her to a work-related illness. As a result, Heather Crowe campaigned for comprehensive smoking bans in the Canadian province of Ontario. On May 28, 2006, four days after her death at the age of 61, her application was granted and a comprehensive nonsmoker protection law was passed.

Mario Labate had worked as a civil servant in the European Commission for 29 years until he developed lung cancer and then died. Before his death, he had brought a lawsuit against the European Commission to have his illness recognized as an occupational illness, arguing that he had been exposed to secondhand smoke from his colleagues for many years. After his death, his widow continued the trial. The medical committee charged with the assessment confirmed the fact that M. Labate was exposed to secondhand smoke and that no other cause for his illness could be found, but that he is also unable to establish a reliable connection between the illness of M. Labate and his professional activity. The lawsuit was denied.

additional

Spending three to four hours in a closed room filled with cigarette smoke (such as in discos or pubs) corresponds to actively smoking four to nine cigarettes, which is due to the toxicity of sidestream smoke in contrast to mainstream smoke inhaled and exhaled by the smoker related. As a result, more and more states have introduced smoking bans for restaurants and public buildings in recent years.

Statistically speaking, children who grow up in a household where one or both parents smoke are more likely to be ill and have a higher risk of cancer. Even intensive ventilation or the furnishing of a smoking room cannot change this problem, as pollutants can remain in the room air for a long time. Studies also show that children of smoking parents later smoke more often themselves than children whose parents are non-smokers.

Nicotine deposits on walls represent a further hazard. A study has shown that the reaction of nicotine with nitrous acid forms carcinogenic nitrosamines, which lead to potential health hazards when dust is touched or inhaled. Inhalation by tar or nicotine stains from tobacco smoke, such as clothes, hair or walls is a residue smoking or third-hand smoke (English third-hand smoking designated).

Scientific evidence

Position of public health organizations

It is the widespread school of thought that inhalation of second-hand smoke is harmful. The link between secondhand smoke and health risks is recognized by every major medical and scientific organization, including:

- The World Health Organization

- The National Institutes of Health

- The German Cancer Research Center

- The German Cancer Aid

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- The Surgeon General of the United States

- The National Cancer Institute

- The Environmental Protection Agency

- The California Environmental Protection Agency

- The American Heart Association , American Lung Association , and American Cancer Society

- The American Medical Association

- The American Academy of Pediatrics

- The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council

- The UK Scientific Committee on Tobacco and Health

- The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has been signed by 168 governments and ratified by 158 governments . The aim of the convention is to protect current and future generations from the devastating health, social and environmental consequences of tobacco consumption and secondhand smoke.

Germany

In addition to the above-mentioned publication by the DKFZ, there are other studies on mortality from passive smoking in Germany. An earlier investigation, which was confirmed by the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, had found at least one death per day from passive smoking. However, this only concerned the number of non-smokers who suffered from lung cancer and died from passive smoking (approx. 400 per year in Germany). According to estimates by other high-ranking German research institutions such as the Robert Koch Institute, the number of non-smokers suffering from lung cancer is much higher. In addition, the majority of second-hand smoke victims do not die of lung cancer, but of coronary heart disease. These were taken into account in the more recent DKFZ study through epidemiological calculations; but the number of 3300 non-smokers killed annually from passive smoke could also be far underestimated. In 2001, the European Union estimated the number of non-smokers killed by passive smoking in Europe at 130–270 deaths per day (50,000–100,000 per year).

Italy

According to a study in the Piedmont region, the number of acute myocardial infarction patients aged up to 60 years in hospitals fell by 11% within five months of the introduction of a smoking ban. Summary: "study, based on a population of about 4 million inhabitants, suggests that smoke-free policies may result in a short-term reduction in admissions for AMI."

A study that included the entire population of Tuscany compared the heart attack rates after the smoking ban (2005) with those of the previous five years and found no association.

Canada

After the introduction of a smoking ban in Toronto city restaurants and bars, the number of emergency rooms with acute cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in clinics fell by a third. In comparison regions without a smoking ban, no statistically significant decreases were found.

New Zealand

A New Zealand study shows the decrease in heart attacks after the introduction of a smoking ban in workplaces. The number of hospital admissions after heart attacks within a period of three years after the introduction of a smoking ban was measured. For people aged 55 to 74, the number of admissions fell by an average of 9%, for non-smokers in this age group by as much as 13%. The rate decreased by 5% in people aged 30 to 54 years.

However, two comprehensive studies from New Zealand found no decrease in heart attack rates attributable to smoking bans.

Switzerland

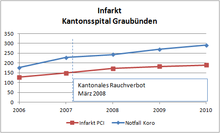

After the introduction of the ban on smoking in restaurants, the number of heart attacks in the canton of Graubünden fell by over a fifth. According to a study, non-smokers have particularly benefited from the Health Protection Act.

The statistics from the Cantonal Hospital of Graubünden, however, come to different conclusions. According to this, the heart attack rates have been rising for several years and the trend has not been broken by the cantonal (2007) or the federal (2010) smoking ban.

Denmark

A graphic published by the Danish government shows no drop in heart attack rates even after the smoking ban.

United States

Since the US government brought the largest tobacco companies to court in the 1990s on the basis of a Mafia law, millions of secret documents by the tobacco companies were released in the course of the negotiations, from which it emerged, among other things, that the tobacco industry was causing death to smokers and passive smokers alike had been known for decades, but publicly denied by tobacco companies until the 1990s. The documents could not yet be fully evaluated due to their number.

The study by Helena found a decrease in heart attacks by 16, from 40 to 24, which the authors attributed to the smoking ban. This corresponds to a reduction of 40%. Overall, the case numbers are statistically extremely meager, as the authors themselves admitted. The authors were just as unable to provide information on passive smoke exposure as they were on the smoking status of the patients. In addition, similar abrupt fluctuations were recorded in the years prior to the smoking ban, as the graphics in the comments on the study show.

The smoking ban only stayed in place for six months. In 2005, the smoking ban was introduced across the state of Montana. Nothing is known of a renewed decline in heart attack rates.

The most comprehensive analysis of the effects of smoking bans for the United States as a whole shows not only that almost all published individual studies are based on cherry-picking , but also that smoking bans do not result in any measurable, short-term effects.

Consequences

The predominantly published opinion created a strong conflict of interest between non-smokers and smokers. The dispute led, among other things, to a general smoking ban on aircraft.

In the meantime, there are far-reaching statutory smoking bans in restaurants up to and including public places in the open air in some countries. Such legal regulations are also required by anti-smoking organizations in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In Switzerland, a general smoking ban in restaurants was enacted at the federal level in May 2010. Small restaurants and smoking rooms are excluded. Most cantons have, however, created stricter laws in the catering industry.

Lobbying and sponsored studies

In Germany, as early as the 1970s, the growing awareness of the dangers of passive smoking was successfully combated through extensive lobbying and marketing activities by the Association of the Cigarette Industry . By influencing scientists and their publications, the association ensured that study results on the harmfulness of passive smoking were suppressed and that the credibility and general validity of research results that were unfavorable for the tobacco industry were questioned.

There is clear evidence that the tobacco industry is still influencing toxicological research today.

Several experts, who judge the dangers of passive smoking as undetectable, are accused of having accepted research funding from the tobacco industry. For example, scientists at an institute in Cologne - which is 100% owned by the cigarette manufacturer Phillip Morris - delivered results that were supposed to downplay the danger. Internal documents from the seven largest tobacco companies that these companies had in the course of several liability lawsuits in the United States (Prosecutor: 40 US Federal states) were forced to publish. The documents, the number of which are in the millions, have not yet been fully evaluated. Much of it was published on the Internet by the US Department of Justice.

See also

literature

- Hans J. Maes: Passive smoking. Documentation of a phenomenon. (Book + CD-ROM). W + D, 1999, ISBN 978-3-934018-01-3 .

- Naomi Oreskes , Erik M. Conway : Die Machiavellis der Wissenschaft (Original: Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming) . Weinheim 2014, ISBN 978-3-527-41211-2 .

- Gisela D. Schäfer: Passive smoking as a risk factor for the manifestation and course of childhood asthma. Inventory and intervention. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 978-3-631-33971-8 .

- Rupert Stettner: Interjection: Comprehensive protection against passive smoking is the competence and duty of the federal government! In: Journal for Legislation (ZG), 22nd year (2007), pp. 156–178.

- Klaus Zapka: Passive smoking and law . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1993, ISBN 978-3-428-07575-1 .

Web links

- The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke A Report of the US Surgeon General, June 2006 - Refer to the report for a thorough evaluation of the effects of passive smoking. Retrieved August 13, 2012

- Passive smoking - kindergesundheit-info.de: independent information service of the Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA)

- Health risk passive smoking . In: GBE compact , 3/2010, Robert Koch Institute

Non smoking / passive smoking protection

- pro aere Swiss Foundation for Passive Smoking Protection and Tobacco Prevention in Children and Adolescents

- Report of the Swiss Federal Council on protection against passive smoking (PDF; 578 kB), March 2006

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz Joseph Dreyhaupt (ed.): VDI-Lexikon Umwelttechnik. VDI-Verlag Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-18-400891-6 , p. 849.

- ↑ Neil E. klepeis, Wayne R. Ott, Paul Switzer: Real-time measurement of outdoor tobacco smoke particles . In: Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association . tape 57 , 2007, p. 522-534 (English). Thick air in the beer garden Report on this on Focus online, May 5, 2007

- ↑ Alan Rodgman; Thomas A. Perfetti: The Chemical Components of Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke , second Edition (February 25, 2013)

- ↑ Section Production, Composition, Use and Regulations (PDF; 1.4 MB) of IARC Monograph 83 from 2004.

- ↑ Chapter “Involuntary Smoking” of IARC Monograph 83 from 2004 (PDF; 2.6 MB), accessed on August 5, 2012.

- ↑ Alphabetical list of IARC classifications. (PDF; 491 kB) Accessed July 31, 2012.

- ↑ TRGS 905 directory of carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction substances ; the technical rules for hazardous substances reflect the state of the art, occupational medicine and industrial hygiene as well as other reliable scientific knowledge for activities with hazardous substances including their classification and labeling, available here as a PDF.

- ↑ Justification for the assessment of substances, activities and processes as carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction for the creation of the technical rules for hazardous substances, available here as a PDF.

- ↑ T Schripp, D brand joke, E Uhde, T. Salthammer: Does e-cigarette consumption cause passive vaping? June 2012, PMID 22672560 .

- ↑ Stefano Zauli Sajani et al .: Urban Air Pollution Monitoring and Correlation Properties between Fixed-Site Stations . (PDF; 472 kB)

- ↑ G. Romagna et al .: Characterization of chemicals released to the environment by electronic cigarettes use . ( Memento from January 18, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 3.2 MB) September 2012

- ↑ Data sheet - Testing the exhaled vapor of e-cigarettes. Wesseling laboratories.

- ^ TR McAuley et al .: Comparison of the effects of e-cigarette vapor and cigarette smoke on indoor air quality . October 2012, doi: 10.3109 / 08958378.2012.724728 .

- ↑ AD Flouris et al .: Acute effects of electronic cigarette and tobacco smoking on complete blood count . In: Food Chem. Toxicol. , October 2012, doi: 10.1016 / j.fct.2012.07.025 .

- ^ Profile Murray Laugesen .

- ^ Murray Laugesen: Safety Report on the Ruyan e-cigarette Cartridge and Inhaled Aerosol . (PDF; 276 kB) 2008.

- ^ Helen Thomson: Electronic Cigarettes - a safe substitute . ( Memento of the original from January 8, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 40 kB) German translation, 2009.

- ↑ Protection of non-smokers in German gastronomy - Why the state laws have failed , DKFZ statement of May 3, 2011 .

- ↑ Third-Hand Smoke: Smoking clothes pollute the air like passive smoking. Retrieved March 6, 2020 .

- ↑ Erica Tennenhouse: 'Thirdhand' smoke can expose moviegoers to the emissions of up to 10 cigarettes . In: Science . March 4, 2020, ISSN 0036-8075 , doi : 10.1126 / science.abb5825 ( sciencemag.org [accessed March 6, 2020]).

- ↑ Roger Sheu, Christof Stönner, Jenna C. Ditto, Thomas Klüpfel, Jonathan Williams: Human transport of thirdhand tobacco smoke: A prominent source of hazardous air pollutants into indoor nonsmoking environments . In: Science Advances . tape 6 , no. March 10 , 2020, ISSN 2375-2548 , p. eaay4109 , doi : 10.1126 / sciadv.aay4109 ( sciencemag.org [accessed March 6, 2020]).

- ↑ a b Passive smoking - an underestimated health risk . (PDF; 3.1 MB) DKFZ Heidelberg, accessed on August 29, 2012

- ↑ a b Whincup. Br. Med. J., doi: 10.1136 / bmj.38146.427188.55 (published 30 June 2004), accessed on August 24, 2012

- ↑ Brunnemann et al. 1990, Löfroth et al. 1989, ARB 1998, Gordon et al. 2002, Hyvärinen et al. 2000, Moshammer et al. 2004

- ↑ Enstrom et al .: Environmental tobacco smoke and tobacco related mortality in a prospective study of Californians, 1960–1998 - bmj.com, doi: 10.1136 / bmj.326.7398.1057 , p. 1057

- ↑ Multicenter Case Control Study of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Lung Cancer in Europe, 1998 - Paolo Boffetta et al. ( Memento of the original from January 13, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 148 kB)

- ↑ Passive smoking - an underestimated health risk , German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg

- ^ A b The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke (PDF) Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Smoking also increases the risk of breast cancer . In: German Cancer Society . October 11, 2010. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved on November 7, 2010.

- ↑ Passive smoking endangers children's lives . In: krebshilfe.de . November 26, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ↑ a b c Passive smoking children (PDF; 365 kB).

- ↑ kindergesundheit-info.de

- ↑ Tobacco smoke makes children hyperactive . ( Memento of the original from January 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , December 3, 2009, accessed on January 26, 2010.

- ^ S. Rückinger, P. Rzehak, CM Chen, S. Sausenthaler, S. Koletzko, CP Bauer, U. Hoffmann, U. Kramer, D. Berdel, A. von Berg, O. Bayer, HE Wichmann, R. von Kries, J. Heinrich: Prenatal and postnatal tobacco exposure and behavioral problems in 10-year-old children: results from the GINI-plus prospective birth cohort study. In: Environmental health perspectives. Volume 118, Number 1, January 2010, pp. 150-154, ISSN 1552-9924 . doi: 10.1289 / ehp.0901209 . PMID 20056582 . PMC 2831960 (free full text).

- ↑ Passive smoking high blood pressure in kindergarten . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , January 11, 2011.

- ↑ a b c - Doctors against smoking damage

- ↑ AFP and Reuters: Health: 600,000 people die annually from passive smoking. In: Zeit Online . November 26, 2010, accessed December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ a b WHO: Only 5.4% of world's population covered by comprehensive smoke-free laws

- ^ Mattias Öberg, Maritta S Jaakkola u. a .: Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. In: The Lancet. 377, 2011, pp. 139-146, doi: 10.1016 / S0140-6736 (10) 61388-8 .

- ↑ Smoking habits in Germany by age group: results of the 2009 microcensus

- ↑ Kathrin Zinkant: health campaign: killing smokers. In: zeit.de . April 1, 2009, accessed December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Rehm et al .; Page no longer available , search in web archives: Comparative analysis of cost-effectiveness of evidence-based measure to reduce smoking-attributable mortality in Switzerland . 2007, financed by the tobacco prevention fund of the Federal Office of Public Health.

- ↑ Compare the law of November 19, 2004 ( BGBl. 2004 II p. 1538 )

- ^ Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- ↑ a b c OVG Lüneburg , DVBl 1989, 935, 936.

- ^ Marko Tartsch: Legal requirements for a federal law on tobacco prevention . Berlin 2009, p. 259

- ↑ Bodo Pieroth , Bernhard Schlink : Basic rights. Constitutional Law II 24th edition Heidelberg 2008, Rn. 370

- ↑ a b c Answer of the Federal Chancellor to a citizen's question

- ↑ a b BVerfGE 121, 317 (350)

- ^ Marko Tartsch: Legal requirements for a federal law on tobacco prevention . Berlin 2009, p. 55 ff.

- ↑ see measures of the Federal Ministry of Health to implement the national health goals . ( Memento of the original from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) health goals.de

- ↑ Passive smoking - an underestimated health risk . (PDF; 1.9 MB) Red Series tobacco prevention and tobacco control, Volume 5. German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Nov. 2005; Page 4.

- ↑ a b c d e BVerfG, judgment of July 30, 2008, Az. 1 BvR 3262/07, 402, 906/08; BVerfGE 121, 317 .

- ^ Smoke-free pubs: The results of the studies ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) . In: Financial Times Deutschland , September 18, 2006

- ↑ Dietmar Jazbinsek: Dying bars ? - The smoking ban disappoints its critics. In: sueddeutsche.de . May 19, 2010, accessed December 27, 2014 .

- ↑ Dietmar Jazbinsek + Felix Berth: The discrete lobby of smokers. In: sueddeutsche.de . May 19, 2010, accessed August 3, 2015 .

- ↑ Action brought on July 31, 2007 - Labate v Commission (PDF; 48 kB), accessed on January 27, 2017.

- ↑ Formation of nitrosamines on walls . organic-chemie.ch; according to: M. Sleiman, LA Gundel u. a .: Formation of carcinogens indoors by surface-mediated reactions of nicotine with nitrous acid, leading to potential third-hand smoke hazards. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107, 2010, pp. 6576-6581, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0912820107 .

- ↑ MH Becquemin, JF Bertholon a. a .: Third-hand smoking: indoor measurements of concentration and sizes of cigarette smoke particles after resuspension. In: Tobacco control. Volume 19, number 4, August 2010, pp. 347-348, ISSN 1468-3318 , doi: 10.1136 / tc.2009.034694 , PMID 20530137 , PMC 2975990 (free full text).

- ↑ JP Winickoff, J. Friebely et al. a .: Beliefs about the health effects of "thirdhand" smoke and home smoking bans. In: Pediatrics. Volume 123, Number 1, January 2009, pp. E74-e79, ISSN 1098-4275 . doi: 10.1542 / peds.2008-2184 . PMID 19117850 .

- ↑ C. Seidler: Doctors warn against smelly clothing. In: Spiegel Online from January 5, 2009

- ^ Budgetary procedure 2011 - Parliament's position. (PDF; 922 kB) European Parliament, session from 28th to 30th September 2010, p. 69.

- ↑ Gladys Kessler: United States of America v. Philip Morris et al. : Final Opinion of Judge Gladys Kessler (PDF; 5.8 MB) United States District Court for the District of Columbia . August 17, 2006. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ↑ World Health Organization , International Agency for Research on Cancer : Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking (PDF), Volume 83, IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Lyon, France 2004, ISBN 92-832-1283-5 .

- ↑ Tobacco-Related Exposures: Environmental Tobacco Smoke (PDF) In: 13th Report on Carcinogens . US National Institutes of Health . Retrieved November 18, 2014.

- ↑ Tobacco - Risk to the Environment and Damage to the Economy, DKFZ publication of December 9, 2009

- ↑ Women, stop smoking! ( Memento of the original from May 25, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Appeal of the German Cancer Aid from October 22, 2001

- ↑ Secondhand Smoke Fact Sheet . US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General . Office on Smoking and Health. 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- ^ Health Effects of Exposure to Environmental Tobacco Smoke . US National Cancer Institute . Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ Health Effects of Exposure to Secondhand Smoke . United States Environmental Protection Agency . Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- ^ Proposed Identification of Environmental Tobacco Smoke as a Toxic Air Contaminant . California Environmental Protection Agency . June 24, 2005. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ The Truth about Secondhand Smoke . American Heart Association . Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Secondhand Smoke Fact Sheet . American Lung Association . Archived from the original on September 18, 2007. Retrieved September 24, 2007.

- ↑ Secondhand Smoke . American Cancer Society . Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ↑ AMA: Surgeon General's secondhand smoke report a wake-up call to lawmakers . American Medical Association . Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Tobacco's Toll: Implications for the Pediatrician . In: Pediatrics , 2001; 107 (4): 794-798, PMID 11335763 .

- ↑ National Response to Passive Smoking in Enclosed Public Places and Workplaces (PDF; 154 kB) Australian National Public Health Partnership. November 2000. Archived from the original on February 12, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

-

↑ Two relevant reports were published by the Scientific Committee:

- A 1998 report from SCOTH concluded that secondhand smoke was a cause of lung cancer, heart disease and other health problems.

- An update of the SCOTH published in 2004 ( Memento of February 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) examined research results published since 1998. The bottom line was that recent research confirms the initially identified link between secondhand smoke and health risks.

- ^ WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) . WHO . Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ↑ Smoke-free workplaces: To improve the health and well-being of employees (PDF), European Status Report 2001, p. 32 (PDF page 38).

- ^ After the smoking ban: Fewer heart attacks in Italy. Retrieved May 29, 2010 .

- ↑ Link to two freely accessible scientific works by Barone-Ardesi

- ^ A. Gasparrini, G. Gorini, A. Barchielli: On the relationship between smoking bans and incidence of acute myocardial infarction. In: European journal of epidemiology. Volume 24, Number 10, 2009, pp. 597-602, ISSN 1573-7284 . doi: 10.1007 / s10654-009-9377-0 . PMID 19649714 .

- ↑ One third fewer heart attacks in Toronto after smoking ban. Retrieved May 29, 2010 .

- ↑ Study: Smoking ban lowers heart attack rates. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; Retrieved March 29, 2010 . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ After the smoke has cleared: Evaluation of the impact of a new national smoke-free law in New Zealand. Retrieved February 5, 2011 .

- ↑ Assessing the effects of the introduction of the New Zealand Smokefree Environment Act 2003 on acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions in Christchurch, New Zealand . PMID 20078567

- ↑ Summaries of the results of these studies can be found here and here .

- ↑ Fewer heart attacks since the smoking ban. Retrieved March 29, 2010 .

- ↑ Annual reports and annual statistics KSGR. (No longer available online.) Cantonal Hospital Graubünden, archived from the original on January 15, 2013 ; accessed on January 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Figure 6, page 42 (PDF; 1.1 MB)

- ↑ Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. Retrieved February 3, 2011 .

- ^ R. P. Sargent: Reduced incidence of admissions for myocardial infarction associated with public smoking ban: before and after study. In: BMJ. 328, 2004, pp. 977-980, doi: 10.1136 / bmj.38055.715683.55 .

- ↑ Kanaka D. Shetty, Thomas DeLeire, Chapin White, Jayanta Bhattacharya: Changes in US hospitalization and mortality rates following smoking bans. In: Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 30, 2011, p. 6, doi: 10.1002 / pam.20548 .

- ^ New Study of National Heart Attack Admissions and Mortality Finds No Evidence of a Short-Term Effect of Smoking Bans. Retrieved July 21, 2012 .

- ^ Thilo Grüning, Anna B. Gilmore, Martin McKee : Tobacco Industry Influence on Science and Scientists in Germany. In: American Journal of Public Health. Vol. 96, no. 1, January 2006, pp. 20–32, doi: 10.2105 / AJPH.2004.061507 , aphapublications.org (PDF; 463 kB)

- ↑ Heike Le Ker, Jens Lubbadeh: Smoking ban: Tobacco lobbyists sense new opportunities . Spiegel Online , July 31, 2008

- ↑ Thomas Kyriss, Nick K. Schneider: Is passive smoking carcinogenic? German toxicologists and their links to the tobacco industry. In: Prevention. Health Promotion Journal. 33rd volume, issue 4/2010, p. 106 ff .; Abridged and edited version: Toxicologists and the tobacco industry - research against the truth . In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . December 23, 2010

- ↑ Annette Bornhäuser, Jennifer McCarthy, Stanton A. Glantz: German Tobacco Industry's Successful Efforts to Maintain Scientific and Political Respectability to Prevent Regulation of Secondhand Smoke . Center for Tobacco Research and Education, University of California, March 2006, dkfz.de (PDF; 1.35 MB)

- ↑ tobaccodocuments.org ( Memento from January 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive )