Second battle of El Alamein

| date | October 23 to November 4, 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | El Alamein , Egypt |

| output | Allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Allies : United Kingdom Australia New Zealand South African Union British India Free France Greece Polish government in exile |

|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| 102,854 men 547 tanks 192 armored cars 675 aircraft (of which 275 German, 150 operational, 400 Italian, 200 operational) 552 guns 469 anti- tank guns |

195,000 man 1,029 tanks 435 armored vehicles around 750 aircraft (of which 530 operate) 908 guns 1451 Pak |

| losses | |

|

2,166 dead |

2,350 dead |

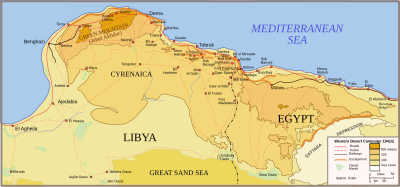

The second battle of El Alamein was a decisive battle of the Second World War in the North African theater of war . It took place between October 23 and November 4, 1942 near El-Alamein in Egypt between units of the German-Italian Panzer Army Africa under the command of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and the British 8th Army under Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery . Rommel had previously pushed the 8th Army back to the east on Egyptian territory up to 100 km from Alexandria , but then could not break through the British defensive position established there, even in multiple attempts. The aim of the major offensive long planned by Montgomery was to destroy the German-Italian forces in North Africa. The Allies were able to rely on their material superiority, while the Axis powers lacked supplies and petrol. The battle ended with an Allied victory and the withdrawal of German-Italian troops.

In the months that followed, the Axis powers had to continue their march back west. So initially the Cyrenaica and finally all of Libya were lost. After the American-British landings in Algeria and Morocco in mid-November 1942, a two-front war developed which ended with the surrender of the German-Italian troops in May 1943 after the Tunisian campaign .

The battle is particularly important in the Anglo-American region, as it put an end to the widespread fear of the Axis powers breaking through to the strategically important Suez Canal . The second battle of El Alamein is largely responsible for the high level of awareness and reputation of Montgomery, also because of the British reporting.

prehistory

From September 1940 onwards, on the direct orders of Benito Mussolini , Italian units advanced to Egypt, where they were able to capture the border town of Sidi Barrani . For this reason, the Allies carried out a counter-offensive under the code name Operation Compass , in which they penetrated 800 kilometers into Libyan territory and inflicted heavy losses on the Italian troops. However, since the British associations were needed in Greece, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill issued an order to halt. At this point the Allies had almost succeeded in driving all Italian contingents out of North Africa.

The first German associations landed in Italian Libya on February 11, 1941 . They were assigned the task of preventing a complete loss of the Italian colony to the British as a blocking association. The German Africa Corps under General der Panzertruppe Erwin Rommel went over to an unauthorized counter-attack, so that the German units were only stopped in April 1941 at Sollum east of Tobruk , which was besieged without success until November 1941.

In November 1941, the Allies carried out a successful counterattack under the code name Operation Crusader . As a result, the Axis powers had to retreat to the starting position, western Cyrenaica . In the course of another offensive from January 1942, the German-Italian associations were able to conquer Tobruk on June 21, 1942.

The advance ended in the first battle of El Alamein , some 100 km west of Alexandria. According to the plans of the Axis powers, a breakthrough of the Alamein position was to be enforced on July 1st, but this did not succeed despite initial successes. Rommel therefore ordered the offensive to be temporarily suspended in order to be able to regroup with a view to resuming the offensive. Based on this information in combination with Ultra knowledge, the allied units for their part unsuccessfully took up the alleged pursuit.

On July 9, all regroupings on the south wing were completed. In the course of the following attack, the straightening of the frontal projection of the New Zealand 2nd Division was given high priority. While the German-Italian attack in the south of the front initially went according to plan, the Allied troops launched an offensive that started at 6 a.m. on July 9th. After the Australian 9th Division had achieved a breakthrough together with the 1st Army Tank Brigade, the tank army had to bring in strong forces to block the breakthrough. This led to the cessation of the German-Italian attack, which was resumed unsuccessfully by the 21st Panzer Division on July 13th.

In the meantime, the results of the radio reconnaissance caused the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces, Claude Auchinleck, to plan another offensive focusing on the front center. Shortly after the start of the attack on July 15, the Allied troops were able to destroy most of the Italian Xth Army Corps, but the 21st Panzer Division was able to stop the Allied advance together with the two reconnaissance departments. Through these and other minor successes, the British Army High Command came to the conclusion that the Italian units were on the verge of collapse. This resulted in the planning of a new attack by the XIII. Corps which, despite strong artillery support, did not achieve its objectives.

After the successful German counterattack on July 22, the New Zealand troops launched another attack, in the course of which they were able to break through the Italian lines and advance to height 63. A counterattack by the 5th Panzer Regiment on the Qattara runway stabilized the situation again. Two other major British attacks failed, so that Auchinleck ordered the offensive operations to be abandoned on July 31.

Since the supply situation continued to deteriorate and there were signs of large Allied reinforcements, the Axis powers planned to force the decision in August 1942. The attack date was originally set around August 26th, but was delayed due to the lack of fuel, which slowed down the gradual relocation of armored forces massively. Albert Kesselring, who at that time held the position of Commander-in-Chief South, gave the final decision to carry out the offensive by ensuring the air transport of fuel stored in Crete and thus preventing Rommel from waiting for the arrival of two tankers whose planned arrival date in Tobruk August 28th and 29th respectively.

On August 30th at 10 p.m. the attack began with the advance of the German-Italian offensive group on the south wing from their starting position between the El-Taqa plateau and the Ruweisat ridge, a little later German-Italian units opened the planned bondage attacks in the northern and central areas Front section. Initially, these went largely according to plan, while the motorized units in the south progressed much more slowly than had been planned in Rommel's plan.

This was due to the sometimes unexpectedly great depth of the minefields and the strong Allied guards at certain points on the front. In the context of the massive Allied air raids, in which two German commanders were killed, as well as the difficult terrain, the German-Italian units found themselves in a difficult situation. On the morning of the following day, the offensive group was only 4 instead of 40 kilometers east of the British minefields.

After Rommel had initially ordered the temporary cessation of the offensive, he decided to continue the attack after assessing the situation. According to the new plan, the DAK had the order, six hours later, at 12 noon (after a later change 1 p.m.), with the 15th Panzer Division on the right and the 21st Panzer Division on the left wing from the northeast in front of the city Himeimat to advance to the height of 132 of the Alam Halfa ridge. The Italian XX. Army Corps (mot.), Which had already got stuck at the foremost mine bolt due to a failure of the mine detectors, slowly moved up and received the order to carry out the northern attack, which had the conquest of Alem el Bueib-Alam el Halfa as its goal, together with the 90th Light Africa Division to continue. In order to continue the attack, the Commander-in-Chief South mobilized all operational dive bombers .

After initial successes, the German tank contingents fell into the deeper sand, which resulted in the consumption of a large amount of fuel. Later, the 15th Panzer Division undertook a comprehensive attack from 6:30 p.m. on the strategically important height 132, which, however, could not be captured despite the tank bases reached by 7:50 p.m. The 21st Panzer Division was meanwhile about four kilometers to the west in firefights with the Allied troops and from 6:30 p.m. curled up near Deir el Tarfa. Meanwhile, the allied associations of the Italian XX. Army Corps (motorized) remained behind, and the Allied troops had succeeded in withdrawing to the north and north-west with minor losses, which is why strong counter-attacks were expected the following day. Furthermore, the strong British-American air strikes continued.

After the temporary cessation of the offensive in the night of August 31st to September 1st, the 15th Panzer Division made one last unsuccessful advance to the height of 132, which failed after defending against a British counterattack due to a lack of fuel. Later, Rommel was informed of the sinking of the expected tankers with the help of Ultra, which largely exposed the tank army to permanent air strikes. In Rommel's assessment, the movement of larger tank units was largely impracticable, which led him to reflect on an early termination of the offensive, which the Commander-in-Chief had carried out after the aerial reconnaissance had seen superior tank units. After the air raids had reached a peak the day before, they subsided again on September 4th and, together with the improved fuel situation, enabled an orderly retreat to the starting position, based on the minefields previously conquered, by September 6th.

Starting position

Location of the Axis Powers

Strategic-operational situation

At the end of September 1942, Rommel gave a lecture to Adolf Hitler in which he continued to assess the supply situation in the Panzer Army Africa as "extremely critical". Without a solution to this problem, according to Rommel, the African theater of war could not be maintained.

Rommel also reported that the first signs of US material infiltration (airplanes, tanks and motor vehicles, closed air force units) could already be seen. He also reported that the British Air Force had demonstrated its extraordinary strength, the British artillery was mobile and used in large numbers with inexhaustible masses of ammunition. Rommel criticized the Italian associations subordinate to him that they had "failed again" mainly due to structural problems. The Italian associations are not on the offensive and can only be used on the defensive with German support.

For a resumption of offensive operations, the Commander in Chief of the Panzer Army Africa set the following conditions:

- the replenishment of the German associations,

- the improvement of the supply situation,

- the appointment of a "German authorized representative for the entire Europe-Africa transport system".

Rommel had already unsuccessfully made some of the demands before the Battle of Alam Halfa. As he knew, the prospects of a resumption of the offensive were slim, despite his optimism shown by Benito Mussolini on September 24th. The great confidence in the Fuehrer's headquarters made him all the more affected, and the propaganda of the Reich Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels forced Rommel to strengthen his optimism even further by appearing at large public events and in press conferences. He regretted this in retrospect.

The battered condition of Rommel, who had already suffered from stomach problems before the battle of Alam Halfa, had not improved significantly, so that at the beginning of September he gave in to the urgent advice of his doctor and showed himself ready for a longer stay in Europe. On his way to his home in Wiener Neustadt , where Rommel had been the commander of a war school before the outbreak of war, he gave lectures to Cavallero, Mussolini and Hitler. However, he left the theater of war with mixed feelings, as Rommel assumed that Winston Churchill would begin a major offensive in Egypt within the next four to six weeks. Rommel saw an offensive in the Caucasus as the only way to stop this project. Other important executives were temporarily absent due to injury or illness, such as Alfred Gause , Chief of the General Staff of the Panzer Army and both his IC and the Ia, Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin and Siegfried Westphal . Furthermore, during the last ten days, all division commanders and the commanding general of the Africa Corps had changed, Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma had taken over the leadership of the corps from Major General Gustav von Vaerst . The representation of the army commander in chief by General of the Panzer Troop Georg Stumme also proved to be problematic . Although he was an experienced commander of tank units, he had not yet fought on African soil, had a heart condition and, as a convict of war, was mainly under probation before Hitler. In June 1942, Stumme was in dramatic circumstances as commander of the XXXX. Panzer Corps released shortly before the start of the summer offensive, albeit without direct guilt. In the meantime, Erwin Rommel, who was absent, kept himself informed of the current situation in Wiener Neustadt and was ready to return to the front immediately when the British offensive began.

Considerations of the various management levels

Hitler, who had promised, among other things, the transfer of a Nebelwerfer brigade with 500 pipes and 40 Panzerkampfwagen VI Tiger and assault guns, some with sieve ferries , did not keep his promises, like the Italian Chief of the Army General Staff Ugo Cavallero with his promises of fuel. Only Mussolini hadn't made any promises and was already looking resigned. In his opinion, the war in the Mediterranean was "temporarily lost". Italy “no longer has enough shipping space”, and next year “the USA will land in North Africa”. In Rommel's opinion, a fake attack was possible in October 1942, and provided that the supply situation was favorable, "the decisive attack", which would become very difficult, in the middle of winter [...]. Mussolini finally agreed with this view.

In retrospect, Rommel suspected that the Duce hadn't grasped the grave situation. He thought Rommel was a physically and morally broken man, which is why he also calculated on the replacement of the commander in chief of the tank army. Ultimately, despite Rommel's efforts, nothing changed for the better; the unloaded tonnage sank since July 1942, whereby after another smaller peak in July it fell again in August, rose again in September and fell again in October.

Replenishment

Since the beginning of the fighting in the African theater of war, both sides had been confronted with the problem that the desert offered no resources to supply the troops. This was of great significance for the Axis Powers, as they, unlike the British, had no supply base on the African continent and so the entire supply situation depended on sea transport from Italy. Furthermore, with increasing German-Italian success, the distance between the ports and the actual front also proved to be problematic. To illustrate the distances, the Israeli historian Martin van Creveld gives the example that the distance between Tripoli and Alexandria was around 1930 km, which is roughly double the distance between Brest-Litovsk on the German-Soviet demarcation line and Moscow. In addition, there were only a few railway sections, so the majority of the route had to be covered by highways, of which the Via Balbia , which was both vulnerable to weather and air raids, was the only one in Libya.

The lack of experience in the desert war also led to the malnutrition of the soldiers, whose rations contained too much fat. This in turn was partly responsible for the general opinion that a stationing in Libya for more than two years could result in permanent health damage for the person concerned. Furthermore, engine wear increased due to overheating, which was particularly noticeable in the motorcycles used. However, the tank engines were also severely affected, so that their service life was reduced from about 2250-2600 km to about 480-1450 km. At the time of the German landing in North Africa, when the front had stabilized near Sirte by the withdrawal of British units to Greece, Mussolini pointed out to the German Plenipotentiary General at the headquarters of the Italian Wehrmacht, Enno von Rintelen , that the supply lines to Tripoli were with them about 480 km 1 ½ times as long as they could normally be effectively accomplished due to the lack of a railway connection.

Over the entire period of the fighting in the North African theater of war, the disproportionately high demand for motor vehicles to maintain a stable supply situation also proved to be highly problematic. Creveld states that the Afrikakorps received ten times as much motorized transport capacity in relation to the forces provided for the planned operation Barbarossa.

Another significant problem was the inadequate port capacities, which meanwhile led to the Tunisian port of Bizerta being used to unload cargo from Italy after negotiations with the Vichy government. By the summer of 1941, however, not a single Axis ship had entered Bizerta. Creveld gives the reasons for this that the French were alarmed after the British occupation of Syria and that the German authorities also had their reasons, which he does not elaborate on. The recapture of the port of Benghazi, which was closer to the front, did not solve the problem at all, since instead of the theoretically possible 2700 tons a day a maximum of 700-800 tons of cargo could be unloaded. The reason for this was that Benghazi was within range of the Royal Air Force and was therefore attacked frequently. Creveld also doubts that the capture of the port of Tobruk in 1941, which offered a theoretical capacity of 1500 tons per day but which was only partially used in practice with a maximum of 600 tons of cargo unloaded daily, would have solved the problem of the lack of capacity.

Beginning at the beginning of June 1941, when the X. Fliegerkorps, which had previously protected the convoys, was relocated to Greece, the loss rate among the German-Italian convoys rose massively, and the British bases on Malta, among others, were able to recover. The situation only eased at the beginning of Rommel's second offensive in January 1942, when the absolute loss of shipping space fell by 18,908 GRT despite an increase in the total cargo shipped to Libya by 17,934 t. After falling steadily from January to April, losses rose in May and June to multiply in August after falling in July.

At the beginning of September the bread ration had to be halved due to a lack of flour and the coveted additional rations had to be completely eliminated. In addition to flour, the army also lacked fat . During this time, the number of sick people in the individual associations continued to rise, which was due, among other things, to malnutrition . Furthermore, the amount of fuel available did not allow any major movements of the motorized troops, and the ammunition stocks remained scarce.

After Georg Stumme had taken over the command of the army due to Rommel's absence - he had started a cure on the advice of his doctor - he demanded a complete reorganization of the care in the sense of Rommel, but showed himself in part in a personal letter that contained his demands already resigned and hoped for Rommel's return soon. At the beginning of the British major offensive, the Commander-in-Chief of the South, Albert Kesselring , as well as the Panzer Army Africa itself, found the fuel situation serious and therefore ordered air transport. On the same day the air force flew over 100 tons of petrol from Maleme on Crete to Tobruk .

Food and ammunition stocks improved slightly in October. However, 30% of the army's motor vehicles were in the process of being repaired at the time, and water supplies were also problematic due to various storms. As a result, the high command of the Panzer Army was forced to determine on October 23, the day the attack began, "that the army does not have the undeniably necessary operational freedom of movement with the current fuel situation".

The high losses, which had risen rapidly since June 1942, also proved to be problematic for the Panzer Army. In the battle of Alam Halfa alone, the Africa tank army lost numerous tanks and other vehicles and 2910 soldiers in eight days. By supplying mainly infantry (the bulk of the 164th Infantry Division was flown in from Crete - albeit with only a few heavy weapons -) the German high command tried to refresh the weakened forces in Egypt.

Defense preparations

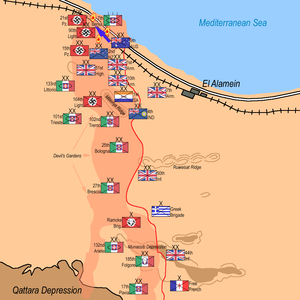

Immediately after the retreat of the offensive group on the south wing in the battle of Alam Halfa, the high command of the Panzer Army Africa ordered the construction of a new line of defense, which should be based on the newly conquered British minefields. The new defensive front consisted of two lines. In the first line stood the Italian troops, the second line was formed by the Africa Corps, which acted as an intervention reserve.

The northern section (coast to Deir Umm Khawabir) was, as before, by the Italian XXI, consisting of the infantry divisions Bologna and Trento. Army Corps defended together with the German 164th Light Africa Division . In the central section (to Deir el Munassib) the Italian Xth Army Corps with the Infantry Division Brescia and the Motorized Division Trieste as well as the 90th Light Africa Division together with the Ramcke Jägerbrigade were stationed. To the south of it stood the Italian XX in the section to Qaret el Himeimat. Army Corps (motorized), consisting of the two weakened armored divisions Ariete and Littorio with the Folgore paratrooper division and the German reconnaissance group.

The Africa Corps was with the majority of its forces behind the Italian XX. Army Corps placed, with two combat groups behind the Italian XXI. Army Corps were deployed. By September 18, the Italian XX. Army corps also held back as a reserve, which meant that the two Italian infantry corps had to occupy the positions alone. The division was that the XXI. Army Corps together with half of the Ramcke Brigade secured the north as before, while the Xth Army Corps, with the reinforcement of the paratroopers of the Folgore Division and the Ramcke Brigade, had to guard the position in the area from Deir Umm Khawabir to Qaret el Himeimat. The southern flank of the corps was secured by a reinforced reconnaissance department. Behind the northern part of the northern section the Littorio Panzer Division was stationed together with the 15th Panzer Division as an intervention reserve, in the north of the southern section the Ariete Panzer Division and the 21st Panzer Division were each deployed in three joint combat groups so that the bulk of the divisional artillery was deployed Barrage in front of the main battle line (HKL) of the XXI. and the X Army Corps could shoot. The distribution of the German army artillery was divided into several groups over the entire breadth of the front.

Due to a failed commando company against the supply nodes Tobruk, Benghazi and Barce on September 13 and 14, 1942, the flank protection received special attention. The Siwa oasis was covered by the Italian Young Fascist division together with an Italian and a German reconnaissance department. The task of the 90th light Africa division was to protect the area around El Daba on the coast together with Sonderverband 288 . In addition, the Italian Pavia division was available with another German reconnaissance department in the Marsa Matruh area, which it was supposed to defend against possible landings and attempted northern bypasses by the British army.

In its defense preparations, the Panzer Army used the so-called “corset rod principle”, which was already successfully practiced before the battle of Alam Halfa. The "corset pole principle" was the insertion of German battalions between the Italian infantry battalions and was practiced especially on sections of the front with critical situations. However, the associations were not integrated into one another, but continued to be subordinate to the national command authorities. In order to improve cooperation, the command posts were placed very close to one another and the same orders were issued, with the German General Staff occasionally making suggestions for the deployment of the Italian troops, as their leadership was considered “indecisive”.

At the end of September, the high command of the Panzer Army Africa ordered a staggered loosening due to the losses in the previous positional warfare. The front mine barriers were only guarded by outpost strips at a depth of 500 to 1000 meters. Behind it was a mile or two of empty space, behind which the new main battle line lay in the back half of the minefields. To defend the new HKL, Rommel ordered the reinforcement of the rear mine barriers, for which various explosives such as aerial bombs were used due to a lack of mines. These minefields were called "Devil's Gardens". The main battlefield adjoining the HKL was around two kilometers deep, and a battalion was assigned a section about 1.5 kilometers wide and five kilometers deep.

All possible defensive measures were carried out, which meant that almost the entire planned depth structure of the Panzer Army Africa was already completed on October 20th. Only the mining of the coastal section was not yet completed. In the course of this work, 264,358 mines had been laid by German and Italian pioneers since July 5, 1942, which led to a total of 445,358 mines including the former Allied minefields.

Enemy reconnaissance

Beginning at the beginning of October there were increasing signs of an imminent major offensive by the British 8th Army under Bernard Montgomery. Like Rommel, Stumme was of the opinion that the best solution would be an advance with an offensive of his own, which he also wrote on October 3 in his letter to Ugo Cavallero . The Commander in Chief of the Panzer Army Africa added, however, that the supply would not be sufficient in the near future and that a counterattack from the defensive would be more likely. This should aim at the destruction of the 8th Army and subsequently the capture of Alexandria.

In the high command of the Panzer Army Africa, the exact British offensive intentions were considered in a differentiated manner: An offensive was expected that extended over the entire front. The focus could, as stated by the reconnaissance group, be between Himeimat and Deir el Munassib in the south of the front, but stronger contingents of troops were expected along the coastal road. From the middle of the month, the start of the attack was expected almost every day, after the 8th Army was considered to be fully replenished. The Panzer Army was therefore surprised not with regard to the time of attack, but with regard to the focus of the British attack.

A daily order of the Panzer Army Africa of October 15 named as possible locations for a breakthrough attempt:

- on both sides of Deir el Munassib and south (on October 23 there were only diversionary attacks)

- El Ruweisat on both sides (there were no British attacks there)

- on and south of the coastal road (this section was assigned to the Australian associations).

The German reconnaissance did not recognize the main thrust of the offensive from October 23 in the west and north-west of the city of El Alamein. In this section in the north of the Alamein Front stood only the 15th Panzer Division and not the 21st Panzer Division , which had been left in the south due to the main direction of attack expected there. Since the German aerial reconnaissance could not see the British focus due to its problems, which came close to a total failure, the two tank divisions, which represented the main striking force of the tank army, were too far apart to implement the operational defense concept developed on October 15 with immediate effect . This envisaged encircling the enemy troops that had broken through "with the motorized forces under tied forces in the front in a pincer-like counterattack" and then immediately destroying them.

The High Command of the Panzer Army Africa was not influenced by the opinion of the Chief of the Foreign Armies West Department in the General Staff of the Army, Colonel i. G. Liß, who had visited the army on October 20th and did not believe in the major offensive even after the start of the attack. Liß saw the signs of a US-British landing in north-west Africa merely indicating the offensive in Egypt, which he expected to begin in early November.

By October 28, the Panzer Army largely identified the enemy division:

| British 8th Army (Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery) | |||

| X Corps | |||

| 1st Armored Division | |||

| 10th Armored Division | |||

| XIII Corps | |||

| 50th (Northumbrian) Division | |||

| 44th (Home Counties) Division | |||

| 7th Armored Division | |||

| 5th Indian Infantry Division | |||

| XXX Corps | |||

| Australian 9th Division | |||

| 51st (Highland) Division | |||

| New Zealand 2nd Division | |||

| South African 1st Division | |||

Allied situation

Allied attack preparations

The Commander of the British 8th Army, Bernard Montgomery, with the support of the British Commander-in-Chief in the Middle East, Harold Alexander , was able to carry out the complete reconstruction of the army and complete it before the offensive began. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill repeatedly pushed for an earlier date for the attack to begin, but the two planners were not influenced by it. In response to Churchill's request for an offensive to begin in September, Montgomery and Alexander announced that they had estimated the start of the attack for the end of October. The British Prime Minister finally gave up and replied: "We are in your hands."

After the victory in the Battle of Alam Halfa, Montgomery's reputation rose sharply. He made major changes in the commanders, ranging from the generals to the division commanders down to the colonels, appointed the experienced Herbert Lumsden , who had previously commanded the 1st Panzer Division, as commander of the Xth Army Corps, which had been elevated to the elite corps, and also the training he headed the army himself. Montgomery got rid of details of the army command by appointing a chief of the army general staff on the German model. He was entrusted with the task of coordinating the work of the staff, although a position like this was rather unusual in Great Britain. Brigadier Freddie de Guingand took over the newly created post . With his personality, he was also able in this position to compensate for Montgomery's inability to deal with other people.

After the army was restructured, three different types of divisions were available:

- the armored (armored),

- the motorized (light, mixed),

- the infantry divisions.

By September 11th, 318 Shermans and self-propelled guns had arrived in Africa, the personnel had been trained and the USAAF already had its own commands and staffs, but they were dependent on cooperation with the British leadership. The offensive was planned down to the smallest detail. Already Claude Auchinleck , the predecessor Montgomery had ordered the preparation of an offensive in July 1942, should have their focus in the north. The reason for choosing the northern section was that in this part of the front the Allied material superiority could be better used than in the south. The importance of this point of view was reinforced before the start of the British offensive in October by the intensive and extensive defense preparations of the Africa Armored Army in the southern sector. Immediately after his arrival, the new Commander-in-Chief of the British 8th Army prepared the complete offensive plan on his own within a week of his arrival in Egypt, which he presented to the 13 commanding generals and division commanders as well as the staff in the Army High Command on 14 September to work out further details.

Allied planning

This concept with the code name Operation Lightfoot , according to Montgomery, had the goal of destroying the forces opposing the Eighth Army. According to the plans, the tank army bound in its positions should be destroyed. In the event that German or Italian troops unexpectedly broke west, the plan was to pursue them and take care of them later. The attack should in the moonlight of October 23, 1942 by the simultaneous beginning of the advance of the XXX. Corps in the north and the XIII. Corps begin in the southern sector, although it was intended to bring about the decision in the north. The task of the XXX. (Infantry) corps was to advance into the German-Italian minefields with very strong support from the artillery, either to push back or to destroy the troops of the Axis powers and then to clear the mines. The newly gained space was to serve as a bridgehead for the X. (Panzer) Corps for the further advance towards the west, "in order to exploit the success and complete the victory".

For the following morning, this X. Corps, which was Montgomery's main thrust, was instructed to cross the "Devil's Garden" into two corridors with the 1st and 10th Panzer Divisions at the break of dawn. Then it was supposed to hold out behind it and finally into A pincer attack took the rear area of the Panzer Army Africa, which blocked the Kattara runway (telegraph or Ariete runway of the Panzer Army) extending from north to south. The runway was the most important route for local supplies for the army, as this runway, which ran behind the main battle line, connected the position front with the coastal road.

The advance of the XIII, which consisted of a tank and two infantry divisions. Corps on the south wing mainly served to divert and bind the German-Italian troops. However, limited objectives were also created for the corps. During the advance, Qaret el Himeimat was to be brought under British control again and, if the situation was favorable, the 4th Tank Brigade was to advance to El Daba so that the supply depots and airfields there could be withdrawn from the Axis powers. Montgomery's plan ended with the summarized principles, which he constantly impressed on his troops without showing signs of fatigue: If the offensive was successful, it would bring about the end of the war in the North African theater of war in addition to cleaning operations, yes: “It will be the turning point of the whole war ", which means something like:" It will be the turning point of the entire war. "In his opinion, the will to win and the morale of the 8th Army are also of great importance, because" no tip and run tactics in this battle, it will be a killing match; the German is a good soldier and the only way to beat him is to kill him in battle. "

However, Montgomery was forced to change plans on October 6th. The start of the attack was already fixed on October 23, 1942 and the Commander in Chief of the British 8th Army also knew that the result of Operation Torch , the Allied landing in French North Africa, as well as the behavior of the French resident there and the extent of the US engagements in the Mediterranean region depended on the outcome of this offensive.

The background to the change in the British attack plan was an analysis by the intelligence department in the army staff, according to which the defense system of the Armored Army Africa would be more complicated than originally assumed. In addition to this problem, the level of the army's current level of training was also deemed unsatisfactory and the commanders of the tank units were against the previous plan. Above all, the commanding general of the new elite corps, the X Corps, Lumsden, to which Montgomery had assigned the decisive role, predicted problems for his corps' tanks to break out of the minefield to the west. He complained about the role of his unit, which was only supposed to operate as a support to the infantry. According to the new attack concept, the XXX. Corps and X Corps now begin their advance at the same time, so that tanks can support the infantry and vice versa.

The problem of the concentration of the two corps in one combat sector was still not solved. Montgomery cleared Lumsden's concerns by issuing an order stating that the tanks should take up a position within the German-Italian minefields to cover the combat against the opposing infantry. For this reason, the two German tank divisions, which were the main thrust of the Panzer Army Africa, would have been forced to attack the X. Corps, which, as in the battle of Alam Halfa, was made up of a large number of superior tanks and tank guns on a large steel wall would have failed. At the beginning of the decisive battle in North Africa on the moonlit night of October 23rd to 24th, the German-Italian forces were in every way inferior to the 8th Army in terms of both material and personnel.

Balance of power

Four days before the start of the attack, the Panzer Army reported the existence of 273 operational German and 289 Italian battle tanks, which meant an increase in German models by 39 and a failure of 34 Italian tanks compared to the level five days earlier. Of these 273 German tanks, however, only 123 were modern models. Among them were 88 Panzerkampfwagen III with the long 5 cm KwK, seven Panzerkampfwagen IV with the short 7.5 cm KwK and 28 with the long 7.5 cm KwK. The Italian models had only a low combat value compared to the British and US American tank types. In contrast to this, the British 8th Army was able to muster a superior force of 1,029 operational tanks on the day of the attack, which could be reinforced by 200 vehicles held in reserve and 1,000 vehicles being repaired and converted. Almost half of the ready-to-use tanks were American tank types, made up of 170 grants and 252 Shermans , whose front armor could only be penetrated by the 8.8 cm flak. On October 23, these contingents faced 250 German tanks.

The situation with the air force was similar. Despite many tactical missions by the German and Italian air forces in September and October, it could not be prevented that the British Royal Air Force increasingly gained air control over the rear area of the tank army. The two attacks by the X. Air Corps at the end of September on the British supply base in the Nile Delta with eight and five aircraft respectively did little to change this. In total, the German Air Fleet 2 with 914 aircraft (528 ready for action) for the entire Mediterranean area faced 96 allied squadrons with over 1500 aircraft that were operating in the Middle East under the command of Air Marshal Arthur Tedder .

Previously, the Axis air force had once again undertaken a major attack against Malta with enormous effort in October, but this failed due to the British air defense. The British night raids with Wellington bombers against the Italian convoys therefore continued unchanged.

In terms of artillery, too, the material superiority of the Commonwealth troops over the German-Italian units was as great as it was with the air forces and armored weapons. In the run-up to the battle, the Allied troops were able to muster over 900 field artillery pieces and medium artillery pieces. In addition, the Commonwealth troops had 554 2-pounder and 849 6-pounder anti-tank guns available. Panzerarmee Afrika used a variety of different anti-tank weapons, of which the 7.5 cm PaK 40 and the 5 cm PaK 38 were the most effective. On the eve of the battle, 68 units of the PaK 40 and 290 units of the PaK 38 were available. In addition, as of October 1, 1942, the Panzer Army was able to deploy 86 8.8 cm FlaKs , of which only some were used for fighting tanks.

A total of around 152,000 Axis forces were on Egyptian soil three days before the start of the battle on October 23 . This contingent consisted of 90,000 German and 62,000 Italian troops. Of these, 48,854 German and 54,000 Italian soldiers were under the command of the Panzer Army Africa. If these numbers are reduced to the actual combat strength, which is known only from the German troops, the strength of the German contingents consisting of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions, the 90th and 164th Light Africa Divisions, the higher artillery commander Africa and the two tactically subordinate large units of the Luftwaffe from the 19th Flak Division and the Luftwaffe Jägerbrigade 1 a total of 28,104 men, who were reinforced by 4,370 men in alarm units from the staffs and supply troops. The total combat strength of the German units was therefore 32,474 soldiers. Assuming a similar strength of the Italian contingents of two tank divisions as well as a motorized, an infantry and a fighter division results in an approximate total combat strength of the tank army of around 60,000 men.

If the term “fighting strength”, used by Ian Stanley Ord Playfair, were to be equated with the German word battle strength, the German-Italian troops would be compared to units of 195,000 British, Australian, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians, Poles and the French, which is more than three times superior of allied contingents would mean. In the Luftwaffe, not to mention the difference between the navies, the superiority was arguably even greater.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Course of the battle

October 26, 1942 5 pm - The 51st Highland Division conquers Kidney Ridge - further attacks get stuck in counterattacks by the "Littorio".

October 26, 1942 5:30 pm - The 2nd New Zealand Division and 1st South African Infantry Division attack the 102nd Motorized Division “Trento”.

October 27, 1942 10 a.m. - The 7th Bersaglieri Regiment tries in vain to evict the 9th Australian Division from Hill 28.

The 44th Infantry Division fights with the "Folgore".

The 7th Armored Division is relocated north.

The "Trento" division falls behind under heavy attacks by the 1st South African and 4th Indian divisions. The 21st Panzer Division and the "Littorio" Division succeeded in counter-attacking to stabilize the front.

The 2nd New Zealand Division is positioned behind the 9th Australian Division.

November 2, 1942 9 a.m. - 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions counterattack - Tel el Aqqaqir tank battle.

Rommel orders the 132nd Armored Division “Ariete” to the north.

November 2, 1942 10 pm - The divisions "Trento", "Bologna", "Pavia", "Brescia" and "Folgore" to the south of Tel el Aqqaqir as well as the paratrooper brigade "Ramcke" begin to withdraw.

1st Armored and 10th Armored are the first to break through and advance along the coast.

2nd New Zealand breaks through in the direction of Fuka and destroys the “Trento” and “Bologna” divisions on the way.

7th Armored breaks through, surrounds and destroys the armored division "Ariete".

Axis troops begin an uncontrolled escape to the west.

Operation Lightfoot

First allied successes

On October 23, around 8:40 p.m. according to the German time calculation, according to the British time calculation at 9:25 p.m. in the southern section and at 9:40 p.m. in the northern section, the British XXX began. Corps with its artillery preparation. 456 guns took part in the barrage, which lasted 15 minutes. Meanwhile, RAF Wellington bombers launched an air raid on identified German positions, dropping a total of 125 tons of bombs. After Ian Stanley Ord Playfair opened the XIII. Corps in the south with 136 guns the artillery fire, but according to Reinhard Stumpf it was soon concentrated on the north wing. In the battle, the barrage reached an intensity never seen before in the African theater of war. Rommel later wrote in his memoirs, referring to the artillery fire, “it should stop the entire fighting in front of El Alamein.” In the front section of the XXX. Corps, the barrage was adapted to the needs of the individual divisions, but it continued for another 5½ hours without any break.

The attack of the XXX. Corps, which was divided from north to south into the 9th Australian Division, the 51st Highland Division, the New Zealand 2nd Division and the South African 1st Division, began at 10:00 p.m. The front was nine and a half kilometers wide and ran between Tell el Eisa and Deir Umm Alsha. Each of the divisions was divided into two infantry brigades and one tank regiment, the New Zealand division was subordinate to one tank brigade. The aim of Operation Lightfoot was to reach a line under the code name Oxalic Line in one train, which ran behind the minefield and was about five to eight kilometers away.

The commander in chief of the Panzer Army, Georg Stumme, did not give the artillery permission to fire annihilation fire because there was an acute shortage of ammunition. This turned out to be a serious mistake, as the British units could attack without any disturbance. Even so, parts of the artillery were kept intact by the Stummes order as they were not the target of British air raids. In the north there was a small attack between the coastal road and the rail link, but the German troops were able to stop it. The 51st Highland Division, together with the Australian 9th Division, was able to break into the mine boxes J and L marked with the letters.

The connection between the German Army High Command and the fighting troops was severely disrupted by the action of the drum-fire, and it was only with great effort that Mute could be prevented from going to the front himself, where he could have done little in the dark anyway. At midnight there was still no clear picture of the situation, but the high concentration of forces on certain sections of the front forced the army high command to assume that the expected major offensive had begun.

In the following morning report from October 24th, however, there was only a situation report and no explicit indications that the offensive had begun. This only changed after Hitler's evening request for an assessment of the situation in order to be able to make decisions about Rommel's whereabouts. In the meantime, the army commander in chief had gone to the front together with the army news leader Colonel Büchting in order to clarify the still unclear situation. However, Stumme did not use an escort or radio car like his predecessor Rommel. Büchting was killed by a shot in the head during this visit to the front, while Stumme suffered a heart attack. Thereupon Siegfried Westphal, who was the sole leader of the army after the death of Stummes at that time, replied that the Panzer Army expected the decisive blow on October 25th. He also calculated a longer duration of the fighting.

After Westphal had already informed Rommel of Mute's death by telegram, Hitler personally ordered him to return shortly after midnight in a telephone conversation. Until the arrival of the Commander-in-Chief, Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, who was the commanding general of the Africa Corps at the time, took over the command of the army on his behalf, but without leaving his own command post.

In the meantime the situation had become a little clearer, since radio bearings determined strong accumulations of forces in the north of the front and thus a first indication of the possible main thrust was available. Troops of the British 51st Highland Division, together with troops of the Australian 9th Division, had traversed mine boxes J and L over a width of ten kilometers and broke into the main battle line. This section was defended by the 62nd Infantry Regiment of the Trento Division together with the 382th Grenadier Regiment of the 164th Light Africa Division. The Italian regiment had already withdrawn from its unfinished positions during the Allied artillery preparation. Following the corset bar principle, the two bandages were mixed in to maintain a more stable position. During their attacks, the Allied troops succeeded in destroying the entire Italian regiment except for one company and the isolated 1st battalion of the German regiment after long fighting until the next dawn. In addition, the Trento division lost around 40% of its heavy weapons and artillery.

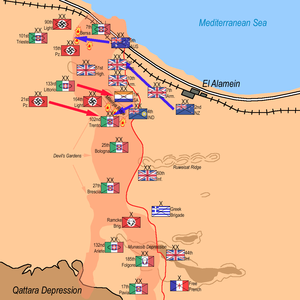

Stabilization of the situation through German-Italian counter-attacks

Due to the tense situation at that time, the 15th Panzer Division, reinforced by the tanks of the Italian Panzer Division Littorio, carried out a counterattack. This cleared the break-in in the main battle line in the early morning of October 24th everywhere except in the northern part of the wedge, so that the successful units were back on the main battle line.

On the following day, the already severely battered 2nd Battalion of the 382 Grenadier Regiment was almost completely destroyed in intense fighting during a renewed attack by the 51st Highland Division from box L. At the same time, the III. Battalion of the Italian 61st Infantry Regiment put down their arms and surrendered. The German 15th Panzer Division was able to stabilize the situation again with full-day counter-attacks and push the attacking units back into the mine box L. These battles had resulted in high losses, so that the 15th Panzer Division only had 31 ready-to-use tanks on the evening of the same day.

At 9:45 p.m. the British troops launched a new attack from boxes J and L after massive barrage had been fired. At this point, the tank army was already in a precarious supply situation, as there were both shortages of fuel and ammunition. In contrast, there were no bottlenecks on the Allied side.

The Allied units also operated offensively in the southern part of the front. North of Qaret el Himeimat, the British 7th Panzer Division with 160 tanks launched an attack on the Italian Parachute Division Folgore. The attack was successful, so parts of the Italian division could be overrun. Counterattacks by the 21st Panzer Division and the Armored Division Ariete stopped the advance, supported by mass artillery fire, but again. The heavily battered Folgore division was able to regroup within a few hours. The commanding officer reported to the German-Italian command level that the combat morale of the division was excellent and that, despite air strikes, it had repulsed superior enemy units. He put the division's losses at 283 men.

The order was then issued to maintain the strategically important height of the Himeimat under all circumstances. Allied attacks on October 25th failed due to resistance from German-Italian troops. In the evening of the same day Rommel arrived at his headquarters via Rome, where he immediately resumed command of the tank army.

In the AOK of the meanwhile renamed German-Italian Panzer Army, the opinion was formed that Montgomery intended a breakthrough in the north in order to then let his troops line up in pursuit. This made it clear that no encirclement of the German-Italian forces from the south was planned.

On the previous night, the Australian 9th Division was able to occupy Height 28, which was north of mine box J, in a successful attack. As a result, further forces were immediately transferred to this part of the front. During the day, the Allied forces carried out several attacks from the gap between boxes J and L towards the west. These had the goal of building a large bridgehead, which should then be used for an advance to the northwest on the coastal road. Allied forces were able to break into the positions of the III. Battalion of the 382th Grenadier Regiment, although the unit had previously been badly hit. The attacks continued to gain strength.

From the course of the battle so far, the AOK came to the conclusion that Montgomery would issue an attack order on the night of October 27th or 27th after almost completely taking the territory between boxes K and J. In the opinion of the high command, this envisaged a major attack via J and L, which should have the thrusts west and northwest.

On the basis of this assessment, Rommel made a decision that was irreversible due to the fuel situation. He arranged for the 21st Panzer Division, with the exception of an intervention group, to move to the north of the front, in the Tell el Aqqaqir area. His order stated that attacks across the entire breadth of the front, which had their focus north of Ruweisat, could be expected at any time. The positions were to be held, although enemy deployments should not be made possible by joint fire of the artillery and anti-aircraft cartillery.

Operation Supercharge

New allied plans

In the high command of the British 8th Army was created on 25/26. October a new battle plan, which, contrary to the original draft, stipulated that the X. Panzer Corps was responsible for mine clearance itself in its combat strip. The background to this rethinking was the unplanned course of the battle. In the first planning, the XXX. Corps should take over the task.

After the judgment of Colonel Richardson, a staff officer of Montgomery, this change resulted in total confusion with the result that the break-in into the German-Italian positions remained unused because the tanks of the X. Corps failed in their advance and got stuck in close combat . Montgomery prompted a major reorganization of its associations.

He moved the 10th Panzer Division with its original position between the 51st Highland Division and the New Zealand 2nd Division to the Australian 9th Division in the north of the front, where the new focus of attack was from now on. Overall, the army commander in chief had turned the placement of his units by exactly 180 degrees. Australian troops, along with the British 10th Armored Division, were to advance north towards the coast. The elite corps, the X. Corps, was assigned the task of making an advance west and north-west from the bridgehead of the 1st Armored Division west of boxes J and L. The surprise effect should be used in this attack. The attack was planned in a meeting with the 2nd New Zealand Division, which took place on October 25 at 12:00. The aim of the attack was to first destroy the armored units in a room of Montgomery's choice, and then to move on to the encirclement of the non-armored units.

The following night, the Australian 9th Division succeeded in capturing Height 28. In conjunction with other British offensive efforts, this prompted Rommel to undertake a major regrouping, by which he exposed the south wing of the tank army. Due to the failure of the advance of the British 1st Armored Division to the west and northwest, Montgomery decided in the evening to restructure its forces in order to free up new potential for the offensive that followed.

It was planned to detach the New Zealand 2nd Division as a reserve from the front by the dawn of October 28 and to relocate the majority of the 7th Panzer Division from south to north. The following night, the Australian 9th Division was to continue its offensive efforts.

At the same time, the British X. Corps was to make preparations to form a shock corps from the reserves, the 9th Panzer Brigade, the 10th Panzer Division and possibly the 7th Panzer Division, according to the original plans. This had the task of completing the breakthrough in order to then take up the pursuit of the enemy units at a suitable time.

On October 29th, Duncan Sandys, the son-in-law of Winston Churchill, brought a telegram from the Prime Minister informing the army of the planned date of attack for the landings in northwest Africa on November 8th. As a result of the reconnaissance, the High Command of the 8th Army received the information on the same day that the German 90th Light Africa Division was being shifted northwards, making it the most northerly positioned unit of the German-Italian Panzer Army. The reason was assumed to be the successful advance of the Australian 9th Division, which was only stopped shortly before the coast road.

Last German-Italian attempts to avert defeat

The already expected major attack finally began at 1:00 a.m. on November 2, 1942 with 7-hour air raids and a 3-hour barrage from over 300 guns. Allied formations attacked on both sides of Height 28, northwest of mine box J with 500 tanks, in order to achieve a breakthrough to the northwest to the coastal road at El Daba. For this purpose, the New Zealand 2nd Division attacked followed by the 1st Panzer Division in two columns, with a massive roller of fire preceded them. After just 15 minutes, the Allied units with Grenadier Regiment 200 of the 90th Light Africa Division managed to break into the position which, according to the battle report of the Panzer Army Africa, “could only be barely sealed off”. A little further south, Allied troops overran battalions of the German 155th Infantry Regiment (90th African Light Division), parts of the Italian Bersaglieri Regiment, the Italian 65th Infantry Regiment (Trieste Division) and a battalion of the German Grenadier Regiment 115 (15th Panzer Division) in the course of a strong tank attack . The infantry spearheads advanced nine kilometers southwest of Sidi Abd el Rahman through the attack to the telegraph runway, and armored forces even managed to advance further beyond the runway.

At the beginning of the following day the Afrikakorps made an unsuccessful attempt with parts of the German and Italian armored divisions (21st Armored Division from the north, 15th Armored Division from the west, Panzer Division Littorio from the south) to clear the four-kilometer-wide incursion. Although the Axis powers managed to shoot down or damage 70 from the point of the armor with 94 tanks, Montgomery continuously supplied his attack wedge with reinforcements from the hinterland so that he could stabilize it. At the same time, the Commander-in-Chief tried to bring about a breakthrough with new attacks, which he succeeded in the morning towards the southwest, where the support of the Littorio armored division and the Trieste motorized division did not arrive in time.

A tough tank battle developed that lasted the whole day. For this battle, Rommel used all of the army and anti-aircraft cartillery for use in ground combat, so that the break-ins could poorly be cleaned up by evening. The promised replenishment, however, fell far short of expectations, so that despite the replenishment of the units from the cables, the combat strength of the tank army had fallen to a third of the level at the start of the battle. The Africa Corps only had around 30 to 35 ready-to-use tanks. At the same time there was a lack of two-thirds of heavy anti-aircraft artillery, primarily the 8.8 cm FlaK 18/36/37 , which were the only effective means of defense against heavy US tanks. The Italian divisions Littorio and Trieste were already showing signs of disintegration. Overall, according to Reinhard Stumpf, the tank army was in a critical situation.

Planned withdrawal and hold order

Due to the situation, Rommel immediately took basic measures. On the afternoon of November 2nd, he put all Italian fast troops back under the command of the XX. Army Corps (mot.), Which stood on the northern section of the front. The armored division Ariete and the motorized division Trieste were relocated from the southern section to the north, so that from now on the defense of the south was again the sole responsibility of the Italian Xth Army Corps, which had no mobile reserves at its disposal. Rommel also instructed the German 125th Infantry Regiment, which had hitherto held its position in the niche on the coast east of Abd el Rahman, to withdraw behind the telegraph runway. The Italian Comando Supremo had meanwhile reported in a radio message at 8:40 a.m. that an attack was imminent on November 2nd or 3rd, although Supercharge had been in progress for almost eight hours at that time.

On the evening of the same day he was informed of Montgomery's mass provision of tanks behind the break-in into the German-Italian lines. In contrast to the Allied masses, the Africa Corps only had a maximum of 35 tanks, so that Rommel was aware of the impending destruction of his army. Due to this fact, the commander-in-chief of the German-Italian tank army gave the order to withdraw gradually to the Fuka position, which had previously been developed in the hinterland . In the south, the units went back to the starting position before the offensive in the Battle of Alam Halfa, with the withdrawal to continue the next day to 15 kilometers southeast of El Daba.

Since Rommel was not sure how Hitler would react to this withdrawal of the units, he sent his orderly officer Berndt to the Fuehrer's headquarters to ask for freedom of action. Meanwhile, the Africa Corps had only 30 tanks. The army commander in chief instructed parts of the Italian infantry that did not have any vehicles to retreat due to the high risk of breakthrough.

The requests of Rommel's orderly officer were in vain, because on November 3rd at 1:30 p.m. an order to stop arrived at the army command post like on the Eastern Front in the winter of 1941/1942. This shocked the commander in chief so much that he later described November 3rd as “one of the most memorable days in history”. He also found that the army had lost all freedom of decision. In the Fiihrer's order, reinforcements were assured in pathetic wording and fanatical will was demanded from the soldiers. Hitler ended his order with the words "You [Rommel] cannot show your troops any other way than to victory or death."

The order, which by no means took into account the actual situation of the army, had an overwhelming effect on Rommel, who had previously always been privileged by Hitler, according to his own statement in his memoirs, so that he described himself as helpless and passed on the stop order out of a "certain apathy". In the following evening report to Hitler, he declared his obedience, but informed him coolly of the high losses, which amounted to around 50% for the infantry, tank destroyers and engineers and around 40% for the artillery. In the Italian divisions Littorio and Trieste, Rommel also reported “very high losses” and he also described the state of the Trento division as “badly damaged”.

The British units reacted to the retreat in the south only in the afternoon, whereby they did not undertake any special attacks until the following morning, so that the majority of the remaining foot troops could have retreated to the Fuka position. This opportunity was missed.

The next day the British XIII. Corps in the south finally moved to the former German main battle line east of El Mireir. Between the Italian XXI. Army Corps, which stood in the middle section, and the Bologna division there was a gap. It had arisen because the division had withdrawn on the evening of November 3rd as originally planned in accordance with Rommel's previous order, without deciphering the later stop order. The officers of the corps staff made an attempt to bring the unit to its starting position south of the Trento division. This failed, however, because on the morning of November 4th a strong, armored British unit of the 7th Panzer Division broke into the positions of the XXI. Corps could achieve. For this reason, the Bologna and Trento divisions fell back. The allied breakthrough finally took place in the Trento division, and the Italian armored division Ariete was completely encompassed from the south. This situation sparked a general crisis within the German-Italian tank army. Finally, after heavy fighting, at 3:30 p.m., the Ariete division was completely surrounded by the north.

In the north of the front, troops of the 8th Army with around 150 tanks and enormous artillery and air support attacked the Africa Corps from 8 a.m. With the personal commitment of his commanding General Thoma, who led the combat squadron on the front line, he succeeded in briefly stopping the attack at the seam between the two German tank divisions. In spite of this, the British 1st and 10th Panzer Divisions achieved breakthroughs in the Africa Corps at various locations by noon, so that the corps was almost completely destroyed in the course of its encirclement by around 150 tanks. The commanding General Thoma was captured by the British.

This breakthrough of the 1st Panzer Division by the Africa Corps at Tell el Manfsra at 3 p.m. to the northwest, the breakthrough of the right wing of the 15th Panzer Division and the breakthrough of the 7th Panzer Division in the Italian XX. Army Corps finally sealed the defeat in this battle. Due to the successes, the 8th Army was now able to attack the German-Italian Panzer Army from the rear area from the open space to the north and northwest. According to Reinhard Stumpf, this in turn made it possible "to unhinge the El Alamein position".

According to Stumpf's statement, “Rommel and his staff saw this development coming”. His anger was undiminished at the rigid, unrealistic stop command, so that when Kesselring arrived, he was upset. The reason for this was that Rommel assumed that Kesselring was indirectly responsible for the Führer's order through his optimistic assessment of the situation. However, Kesselring took a similar position to that of the Commander in Chief of the German-Italian Panzer Army and encouraged Rommel to continue the retreat without Hitler's permission.

Actual withdrawal

In view of the backing of Kesselring, Rommel authorized the 90th Light Africa Division, which protruded far to the east, to retreat to the level of the Africa Corps, if necessary. Between 2 p.m. and 2:15 p.m., the commanding general of the Africa Corps, Fritz Bayerlein, informed the commanders of the two German armored divisions that the 90th African light division and the left wing of the 21st Armored Division adjacent to the south could withdraw if necessary. Bayerlein had taken over command of the corps on behalf of Wilhelm von Thoma, who had been taken prisoner. If the units were withdrawn, they should take up a position south of El Daba, 20 kilometers back from the front.

Rommel issued the final order to retreat to the Fuka position after dark after 3 p.m., as he had been informed of the destruction of the Ariete Panzer Division around ten minutes earlier. As a result, there was now a large gap in the front of the tank army, through which strong British tank units advanced. The Commander-in-Chief had previously asked Hitler for permission to withdraw, but he did not wait for the dictator's answer. While the withdrawal of the front was already in progress, Mussolini and Hitler gave their approval at 8:45 p.m. and 8:50 p.m. after Rommel's orderly officer Berndt gave a lecture at the Fuehrer's headquarters. Meanwhile, Rommel had already admitted his defeat in a radio message intercepted by Ultra on November 4th.

At the beginning of the retreat the Panzer Army had about 30 German and a little more than 10 Italian tanks, which made any mobile operations impossible. The lack of fuel only allowed the army to break away from the Allied forces as directly as possible. In the course of the settling movement, it was often forced to stand still briefly to wait for new fuel to be supplied. The German-Italian units were able to escape from the pursuers, which prevented a significant part of the tank army from being destroyed. While at the beginning of the retreat there was a chaos of backflowing vehicle columns, consisting of parts from various units, the units regrouped after reaching the border with Libya on November 6th. In the meantime, the troops on the vehicles in the withdrawal movement would have had no chance of resisting an unforeseen attack. Numerous soldiers withdrew to the west on foot on the south wing. The Ramcke Air Force Jägerbrigade captured means of transport to retreat through an attack on a British column. The retreat of the German-Italian units was also favored by a "heavy rainstorm" that began on the evening of November 6th, as this made it impossible for the Allied units to pursue the area through the now muddy terrain.

consequences

According to the British historian Ian Stanley Ord Playfair , the British associations recorded around 2350 dead, 8950 wounded and 2260 missing in the course of the offensive. The Desert Air Force lost 77 aircraft, the US Air Force 20 aircraft, while the German Air Force Associations lost 64 and the Italian around 20 aircraft. Furthermore, there were 500 lost tanks in the 8th Army, most of which were repairable, and 111 lost guns of various kinds. Playfair does not give any exact figures for the troop losses on the German and Italian sides, but he described the losses as enormous and viewed the German units as reduced to skeletons, while he viewed the Italian troops as broken. Playfair only provides numerical information for prisoners of war: on November 5, 2,922 Germans and 4,148 Italians had already been taken prisoner. Six days later the numbers were already 7,802 German and 22,071 Italian soldiers. According to him, 36 of the 249 German tanks and around half of the 278 Italian tanks remained, the majority of which were lost in battle with the British 7th Panzer Division by the evening of November 4th.

In Italy, the defeat in battle, the almost complete annihilation of the Trento and Trieste divisions and, above all, the destruction of the active combat units of the Folgore division became a significant factor in the fall of Mussolini in the summer of 1943. The fanatically devoted resistance of the Folgore was indeed from the Duce as an example of the superiority of the Italian troops over the English and strongly emphatized in the government press, but the devastating setback convinced most of the generals, among them Ugo Cavallero and Vittorio Ambrosio , that the war was now lost and a ceasefire was the continuation of the conflict preferable.

With the partial annihilation of the forces of the German-Italian Panzer Army, an initially disorderly retreat from Egypt through Libya began, which took place after crossing the Libyan border on November 6th. Subsequently, the German-Italian forces occupied parts of Tunisia, where a union to Army Group Africa with other units took place. Despite initial success in the Tunisian campaign against the units that landed in the battle of the Kasserin Pass in the course of Operation Torch in North Africa , the German-Italian troops surrendered in May 1943 after several defeats, which means that around 275,000 German and Italian soldiers were taken prisoner, which is measured by the number of the prisoners of war who surrendered to the Soviet units at the end of the battle meant three times the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad . Two months later, the Allied units under the command of Dwight D. Eisenhower began landing in Sicily on July 10, 1943 under the code name Operation Husky . After the completion of this operation, the Allied invasion of Italy began in September 1943 by the 8th Army under Bernard Montgomery and the 5th US Army under Mark W. Clark , which were combined to form the 15th Army Group.

As a result of the landing, Italy broke away from the alliance system with the Nazi state through the armistice of Cassibile on September 3, 1943, after German troops of Army Group B had already occupied northern Italy with Italian consent from August 1. After the announcement of the Italian armistice on September 8, the Commander-in-Chief Albert Kesselring triggered the Axis case , through which the Italian units were disarmed. Two days later, German units occupied the Italian capital, Rome , with the captured Benito Mussolini being freed by a commando two days later . As a result, the Kingdom of Italy declared war on the German Reich on October 13, 1943, although the Italian Social Republic under the leadership of Mussolini had previously been declared on September 23, 1943 . Until the surrender of the German-Italian units in Italy on April 29, 1945, their troops continued to fight together with the German units against the advancing, superior Allied troops.

reception

According to the British historian ISO Playfair, the second battle at El Alamein was the culmination of two years of fighting in the African theater of war, although it differed in many important respects from previous conflicts. Before El Alamein, the Allied units had already been massively superior, but this superiority had never been as complete as in this battle. Playfair also emphasizes that the excess of forces was not only quantitative, but also qualitative. He sees the newly introduced M4 Sherman tanks as the reason for this. Eighth Army's morale was very high during the battle, largely due to this complete superiority. Playfair believes that the most important factor in maintaining high morale is the constant Allied air superiority, which made frequent air strikes possible, while German-Italian aviation units were only able to carry out air strikes on the British rear territory very rarely, and if only with low intensity, but morality is According to the British historian Jonathan Fennell alone, this is not a generally accepted explanation for the results of the battles in the North African theater of war.

Winston Churchill paid tribute to the battle on November 10 with the words

“Now this is not the end, it is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning. "

"This isn't the end yet, it's not even the beginning of the end, but it may be the end of the beginning."

He also said of the battle that "it was different from all previous, heavy fighting in the desert" and draws parallels between El Alamein and the Battle of Cambrai as well as other battles on the Western Front towards the end of the First World War :

“The front was limited, heavily fortified, and held in strength. There was no flank to turn. A break-through must be made by whoever was the stronger and wished to take the offensive. In this way we are led back to the battles of the First World War on the Western Front. We see here repeated in Egypt the same kind of trial of strength as was presented at Cambrai at the end of 1917, and in many battles of 1918, […] ”

“The front was limited, heavily fortified and held by strong forces. There was no flank to avoid. A breakthrough had to be made by whoever was stronger and wanted to take the offensive. In this respect we are being led back to the battles of World War I on the Western Front. Here in Egypt we see the repetition of the same test of strength as it took place at Cambrai at the end of 1917 and in many battles of 1918, [...] "

The British historian Norman Davies describes the withdrawal of the German-Italian units after the defeat in the second battle of El Alamein as "brilliant" and the British Rommel biographer David Fraser also assesses the withdrawal from the Alamein front and the subsequent march back to Tunisia as " undoubtedly exceptional achievements ”. Fraser sees Montgomery's caution and the resulting hesitant pursuit of the troops of the German-Italian tank army as an important factor in the successful withdrawal movement. In his memoirs, Rommel judged that Montgomery had risked nothing; bold solutions were completely alien to this. The criticism of the slow persecution by the 8th Army contrasted Fraser with opposing positions, which ascribed "the half-heartedness of the persecution of the fearfulness of his subordinates and the bad weather".

The German historian Thomas Kubetzky sees Montgomery's victory in the second battle of El Alamein as the basis of his portrayal in British war coverage of the Second World War and its high profile even after the war. In his dissertation, he writes that before taking command of the 8th Army in the summer of 1942, Montgomery was "largely unknown to the general public" and only then slowly a certain media interest in his person arose. The first highlight of the reporting on Montgomery was to be settled at the end of October / beginning of November 1942, whereby he saw the victory in the second battle of El Alamein "as the starting point for the detailed and continuous reporting on Montgomery". Montgomery was raised after the end of the war due to its military successes on January 31, 1946 as Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, of Hindhead in the county of Surrey to the peer and accepted into the Order of the Garter.

In contrast, according to the British military historian Antony Beevor , Montgomery's reputation as an outstanding military leader is more the result of the formation of myths that he sees barely covered by the real events of the battle. Montgomery's decision to attack precisely the strongest part of the German front line was problematic. In fact, the victory is largely due to the Desert Air Force , which destroyed German planes and tanks and disrupted supply lines. Montgomery's 8th Army profited significantly from this, as well as from the measures of the Royal Navy and the air forces of the Allied allies, which disrupted the logistical connections of the armed forces of the Axis powers.

Rommel's media presence peaked between early and mid-1942, and then largely waned again from early autumn 1942 to late 1943. The result of the British victory in the British press was that articles about Rommel always emphasized his final defeat by Montgomery. At the same time, after June / July 1942, Rommel also lost “his previously existing aura of invincibility” in the majority of the British.

Another consequence of the massive media coverage of the battle, according to Kubetzky, is the disappearance of general fear of a German-Italian breakthrough to the Suez Canal. The articles were partly written in factual (for example the New York Times ), partly in very exuberant language (such as the Daily Express ).

The historian Reinhard Stumpf sees the second battle of El Alamein as the cause of a personal alienation between Rommel and Hitler, which, despite attempts by the dictator, was never overcome. This battle was the "decisive turning point in [Rommel's] relationship with Hitler". For a long time after El Alamein, Hitler denied the military necessity of withdrawing from Egypt and, contrary to all reason, refused to admit the Allied material superiority and the lack of fuel. Until the summer of 1944, when Rommel came into contact with the resistance, the dictator claimed that Rommel had merely lost his nerve, since he was not a good "stalker" but only a good operator.