Operation Crusader

| date | November 18, 1941 to January 17 ( February 4 ) 1942 |

|---|---|

| place | North Africa ( Italian Libya , Egypt ) |

| output | allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 118,000 men approx. 730 tanks approx. 700 aircraft |

approx. 119,000 men approx. 400 tanks approx. 500 aircraft |

| losses | |

|

18,600 dead, wounded, missing or prisoners |

a total of 36,427 |

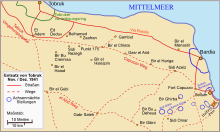

The Operation Crusader (rarely also: Battle of Africa ) was a military operation of the Allies in World War II in North Africa . It lasted from November 18, 1941 to January 17, 1942 and was the third, most extensive, longest and ultimately successful attempt to break the siege of Tobruk by the German Africa Corps . In Germany and Italy, the successful counter-offensive from January 21 to February 4, 1942 is sometimes included in this. The chaotic battles were characterized by logistics problems, misjudgments, communication problems and command crises. The course of Operation Crusader, with its rapid advances, spatial movements and constantly changing initiative, illustrates the characteristic dynamics of the fighting in North Africa like no other military operation.

background

Italy had declared war on France and Great Britain on June 10, 1940. Dictator Benito Mussolini assumed that the war would only be brief and hoped to be able to satisfy some of Italy's territorial claims through an alliance with the German Empire . In North Africa, on the one hand, these consisted of an expansion of the colony of Italian Libya to the west to include the French protectorate of Tunisia . To the east, Italy sought control over Egypt and the strategically important Suez Canal , as well as establishing a direct land connection to its colonies in East Africa . After France had been defeated in the western campaign and Tunisia belonged to the now allied Vichy France , the Italian expansion goals in North Africa turned entirely to Egypt. On September 9, 1940, Italy finally invaded Egypt with the 10th Army .

Course of the war in North Africa

However, the invasion was not very successful and, due to the poor supply and equipment of the troops, it only came to a halt a little more than 100 km behind the Egyptian-Libyan border. On December 8, the Allies launched a counter-offensive with Operation Compass . Originally limited to just a few days and aimed at driving the Italian army out of Egypt, it turned out to be so successful that the advance into Libya was continued. By the beginning of February 1941 the Allied troops had occupied the Cyrenaica up to and including El Agheila and almost completely wiped out the Italian 10th Army.

The complete capture of Italian Libya did not occur, however, because parts of the Allied troops deployed in North Africa were needed to ward off the impending Balkan campaign of the German Reich in April 1941. While the Allies withdrew troops to defend Greece from February 1941 , Germany secretly shipped its first troop contingents to Tripoli in the so-called company Sonnenblume and founded the German Africa Corps . Only a few weeks after his arrival, the Afrikakorps commanded by Erwin Rommel and the Italian divisions in Libya started another offensive. The few and mostly inexperienced Allied troops quickly withdrew from Cyrenaica.

In the course of April, the Axis powers had again advanced to the Halfaya Pass on Egyptian territory. Only the strategically important deep water port of Tobruk was still held by an Allied occupation. After a series of attacks on Tobruk in April and early May 1941 had failed, Rommel prepared for a longer siege of the city in order to save his limited resources . The Allied High Command in the Middle East under Archibald Wavell began planning and preparing a counter-offensive to regain control of Cyrenaica and to relieve the besieged city. The first counter-offensive, called Operation Brevity , started on May 15, but was able to achieve little more than recapturing the Halfaya Pass (and only until May 27). At the same time (May 20 to June 1, 1941) the airborne battle of Crete was fought, which, should the German Reich be successful, would significantly improve air support and supplies to the Axis powers. A second Allied offensive launched on June 15, Operation Battleaxe , failed with great losses of tanks, with the Allied troops barely escaping encirclement and destruction. After this failure, Archibald Wavell was replaced as Commander in Chief of the Middle East Command by Claude Auchinleck .

Military starting position

After the appointment of Claude Auchinleck in July 1941 as the new Commander-in-Chief for the Middle East , the XIII. Corps with the newly established XXX. Corps in the 8th Army under Lt. General Alan Cunningham in summary. The units of the Australian 9th Division in Tobruk were replaced by the British 70th Infantry Division , the Polish Carpathian Brigade and the Czechoslovak Brigade by the Royal Navy under pressure from the Australian Parliament during September and October . The 8th Army was upgraded to 700 tanks (including many of the new Crusader tanks after which the operation was named, American Stuart light tanks , and Matilda and Valentine heavy tanks). About 600 aircraft of the Desert Air Force provided air support . According to the British tank doctrine as should infantry tanks ( Infantry tank developed) Matilda and Valentine tanks the enemy lines with the infantry leave. The fast Crusader and Stuart should as cruiser tank ( Cruiser tank then pierce) the gaps thus created single-handedly and advance into enemy territory. In this operational doctrine of the British, which was largely developed by Percy Hobart , tanks, infantry and artillery acted predominantly as independent units on the battlefield.

On the one hand, the Allied formations faced the Panzergruppe Afrika under General der Panzertruppe Erwin Rommel with the German Africa Corps , consisting of the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions (converted from the 5th Light Division in August; altogether 260 tanks). In addition, the "Africa Division z. b. V. ”(renamed 90th Light Africa Division during the course of the battle ), the Italian infantry division “ Savona ”, and an Italian army corps with four infantry divisions (“ Brescia ”,“ Pavia ”,“ Bologna ”and“ Trento ”). They were also supported by the Italian Mobile Corps (CAM), consisting of the armored division “Ariete” (154 tanks) and the motorized infantry division “Trieste” . The Axis air support consisted of 120 German and 200 Italian aircraft at the beginning of the offensive, but was significantly increased after the attack began. The doctrine practiced by the German armed forces focused on rapid advances in which different branches of the armed forces worked closely together . This should make breakthroughs and, if possible, encircle the opponent . The short-term creation of tailor-made mixed task forces, with which the existing command structure was responded to tactical challenges, was firmly planned in this understanding of operations.

foreplay

Operation Midsummer Night's Dream

In the autumn and winter of 1941, the Axis forces were unanimous in their opinion that the British were preparing a new offensive. Rommel was warned that an attack could still be expected in 1941 and was therefore to postpone his own offensive to 1942 at the earliest. Rommel ignored these warnings and pushed ahead with plans for a major attack on Tobruk. For this, however, it was first necessary to find out whether a British attack was imminent. The usual methods of reconnaissance using armored vehicles and aerial reconnaissance have now been effectively countered by the British. On the ground, the armored cars of the 11th Hussars and other units from the South African Armored Car Regiment , together with jock columns (improvised infantry and artillery units, named after their inventor and commander Jock Campbell) obstructed the German reconnaissance. The RAF had been reinforced and prevented aerial reconnaissance. Therefore, an attack on a British replenishment depot in Bir El Khireigat, suspected by the reconnaissance, was planned. The 21st Panzer Division was supposed to advance, find out as much as possible about a possible British troop concentration, and then return. The attack was scheduled for September 14, 1941.

However, the British intelligence had correctly foreseen this advance and warned Auckinleck accordingly. British troops were instructed not to seek a fight, but instead to avoid the enemy. Auckinleck decided to take the opportunity to leak false information to the Germans by "accidentally" dropping some fake British reports into the hands of the Germans.

The attack was carried out by the three combat groups Schütte (in the north), Stephan (in the middle) and Panzerhagen (in the south). Rommel accompanied Kampfgruppe Schütte in the north in his captured British AEC command vehicle . During the approach to Bir El Khireigat there were isolated skirmishes with British armored vehicles, in which both sides suffered slight losses before the British fell back. Bir El Khireigat was captured but proved to be an insignificant target. However, a truck was also found, which apparently served as a command vehicle for the 4th Battalion of the South African Armored Car Regiment and in which numerous documents and coding materials were found. The combat groups Schütte and Stephan advanced further, but were slowed down by British armored vehicles and artillery fire until they finally ran out of fuel. Rommel's driver was killed in the artillery barrage. Kampfgruppe Panzerhagen was able to advance further and finally dug itself into hedgehog position in the dark . Two attacks on the position were repulsed during the night and at dawn the order came for all combat groups to retreat to their starting positions. British planes bombed the columns and damaged Rommel's vehicle, among other things. Since the British pursuers were already relatively close, Rommel did not dare to send a radio message to ask for help. This showed Rommel's problematic tendency to "lead from the front", even if this was hardly compatible with his position (Rommel was supposed to come into a similarly dangerous situation again in the course of Operation Crusader). Finally the damaged tire could be changed and Rommel reached the German lines unscathed.

Operation Midsummer Night's Dream was a resounding British success. Auckinleck had managed to keep the British deployment completely secret and additionally to feed the enemy with false information. According to the "captured" documents, the British did not plan an attack until December and considered retreating towards Mersa Matruh , which reinforced Rommel in his view of pressing ahead with the attack on Tobruk . The influence of the documents on the German leadership can also be measured by the fact that Rommel first flew to Rome to spend a two-week vacation there with his wife. It was only by chance that he returned in time for Crusader to start.

British plan of attack

Cunningham's plan was to use the XXX. Corps under Charles Norrie with the British 7th Panzer Division and the South African 1st Division to bypass the border fortifications on the Sollum Front at Fort Maddalena to the south and to advance in a north-westerly direction towards Tobruk. The XXX. Corps was to advance to Gabr Saleh, wait there for the German counterattack, which was expected within the first day, and then fight a major, decisive tank battle in which the German tank divisions would be destroyed. According to British doctrine, tanks would fight tanks there and a British victory was expected due to the great numerical superiority.

After the expected battle, the victorious British tanks were to dominate the battlefield and then the connection with the crew of Tobruk, who were to assist in breaking out. The XIII. Corps under Alfred Reade Godwin-Austen with the Indian 4th Division, the New Zealand Division and the 1st Army Tank Brigade should meanwhile undermine the Sollum Front by pushing strong parts through Sidi Omar into the rear of the defending Axis troops and pushing them backwards Cut connections.

The success of the plan thus largely depended on the outcome of the expected tank battle. A major problem with the plan was that even in the planning phase, British people wanted to wait for the counterattack. So the British Army would move forward, dig in, voluntarily surrendering the initiative to the enemy, and then fight a defensive battle. There were no plans for a failure to counterattack, which contributed significantly to the later problems of the operation.

Involved armed forces

Allies

-

Middle East Command (General Claude Auchinleck )

-

8th Army (Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham , Neil Ritchie from November 26, 1941 )

- XXX. Corps (Lieutenant-General Charles Norrie )

- 7th Armored Division (Major-General William Gott )

- 1st South African Infantry Division (Major-General George Brink )

- 22nd Guards Infantry Brigade

-

XIII. Corps (Lieutenant-General Reade Godwin-Austen )

- 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division (Major-General Bernard Freyberg )

- 4th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General Frank Messervy )

- 1st Army Tank Brigade

- XXX. Corps (Lieutenant-General Charles Norrie )

- Garrison Tobruk (Major-General Ronald Scobie )

- 70th Infantry Division

- Polish Carpathian Brigade

- 32nd Army Armored Brigade

-

8th Army (Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham , Neil Ritchie from November 26, 1941 )

Axis powers

- Governor General of Italian Libya General Ettore Bastico

- Italian XX. Corps (Lieutenant-General Gastone Gambara )

- Panzergruppe Afrika (renamed Panzerarmee Afrika on January 30, 1942) (General der Panzertruppe Erwin Rommel)

- German Africa Corps (Lieutenant General Ludwig Crüwell )

- Division z. b. V. Africa (renamed the 90th light Africa division on November 28, 1941) (Major General Max Sümmermann until December 10 (fallen), then Major General Richard Veith )

- 55th North African Infantry Division "Savona" (General Fedele de Giorgis)

- 15th Panzer Division (Major General Walter Neumann-Silkow until December 6th (fallen), then Major General Gustav von Vaerst )

- 21st Panzer Division (Major General Johann von Ravenstein until November 29th (captured), then Major General Karl Böttcher )

- Italian XXI. Corps (Lieutenant General Enea Navarrini )

- German Africa Corps (Lieutenant General Ludwig Crüwell )

Course of the operation

17.-18. November: British march

On the night of November 17th to 18th, the British troops took up their starting positions. Despite various delays, higher fuel consumption than planned and cold rainfalls, all units were ultimately able to take their starting positions. In the early hours of November 18, the 8th Army began its attack from its base in Mersa Matruh in a northwesterly direction. Originally, a strong air support was planned, which should aim primarily at the air forces of the Axis Powers in order to prevent them from attacking the advancing troops. The same storms that had covered the deployment of the 8th Army, however, now prevented the planned use of the Allied air support.

Unlike in previous operations, the radio discipline of the British units was better this time and complete radio silence was observed. The lack of radio traffic from the enemy alerted the German radio reconnaissance. In the morning Kampfgruppe Wechmar - a unit of armored vehicles that patrolled along the border fence together with the Italian Recam - reported contact with British armored vehicles . Both Kampfgruppe Wechmar and Recam were driven out by British tanks in the afternoon and the 8th Army reached its starting position in Gabr Saleh as planned towards evening, even if some units were hanging back. The problem was the poor British tank technology: In the 7th Armored Division, the 7th Armored Brigade lost 22 of its 141 tanks; the 22nd Armored Brigade lost 19 of its 155 tanks. Mechanical problems alone caused a significant percentage of British tanks to fail before the actual battle began. This was all the worse because, unlike the Germans, the British had no mechanics directly integrated into the combat units who could have repaired such failures in the field. In contrast, the American M3 Stuarts were found to be more robust and few mechanical problems were reported.

The XIII. Corps moved as planned in the direction of the enemy garrisons near the border during the day. On the evening of November 18, the infantry units were in the starting positions for an attack on the garrisons. With that, the first phase of the Crusader Plan had been carried out exactly as it was planned.

Rommel had just returned from Rome from a two-week vacation with his wife when Crüwell told him about the British attack. However, Rommel was convinced by the documents captured in Operation Midsummer Night's Dream (see above) that the British could not start an attack before December. He therefore interpreted the British march as a mere battle reconnaissance that was supposed to distract him from the attack on Tobruk planned in two days. Crüwell, on the other hand, correctly interpreted the deployment as a large-scale attack and proposed that the 15th Panzer Division be put in readiness and the tanks of the 21st Panzer Division sent towards the border fence. This proposal was rejected by Rommel with harsh words ( “We mustn't lose our nerve” - Rommel in his answer to Crüwell), which put a strain on the relationship between Rommel and Crüwell. That night, a British soldier was captured in Sidi Omar who testified that the 7th Armored Division had already crossed the border fence. Rommel saw this as another attempt at deception by the British and continued to refuse to take precautionary measures, even if Ravenstein from the 21st Panzer Division agreed with Crüwell.

Curiously, Rommel's colossal misjudgment disrupted the British plans for a long time. After all, the plan was to advance and then wait for the German counterattack. With the scattered documents, improved camouflage and radio discipline, the British had the element of surprise on their side; they held the initiative at this point and faced an opponent who refused to acknowledge the attack - all desirable results but which, thanks to the Crusader plan, could not be exploited by the British. Rommel's inactivity had made the British battle plan obsolete on day one.

November 19th: British attacks

After the lack of German reaction, Cunningham had developed a new plan on the evening of November 18th: Tobruk was to be reached first, then the German tanks would be defeated. This was the exact reverse of the Crusader plan, according to which the tanks should first be destroyed and then Tobruk should be horrified. Cunningham ordered the 7th Armored Division to advance towards Tobruk. Since he withheld the 4th Armored Brigade to keep the XXX. and the XIII. Corps, there were only two units left: 22nd Armored Brigade and 7th Armored Brigade. The 22nd Armored Brigade was to advance against the Italian positions at Bir el Gubi , supported by the 1st South African Brigade, an infantry unit. The last part of the orders was misinterpreted due to communication problems and the 1st South African Brigade therefore did not take part in the fight. The 7th Armored Brigade was supposed to advance to the airfield at Sidi Rezegh . The problem with these orders was the fragmentation of the British tanks, which were now spread over a large area and would now most likely fight in the minority instead of as planned with numerical superiority in the event of a German counterattack.

Nonetheless, the tanks start moving in the morning. Around noon the 22nd Armored Regiment had its first enemy contact with Italian tanks that were deployed as scouts in front of the positions of the Italian 132nd Armored Division Ariete near Bir el Gubi . The 132nd Army Division was supported by artillery and 146 M13 / 40 tanks and had also created numerous fortified positions. The Italian outpost tanks were able to destroy some British tanks but also suffered losses before being pushed back. The British tanks had neither infantry nor artillery support, which according to British tank doctrine should not play a role and therefore attacked head-on. The inexperienced tank crews drove towards the Italians at high speed, like a cavalry attack. The terrain was flat and littered with Italian positions, which is why the British quickly suffered heavy losses. Although they were able to push in the right Italian flank and take numerous prisoners, their advance was quickly halted by further reinforcements. With no infantry support, the tanks were also unable to hold onto Italian prisoners of war, so many of them picked up their weapons and returned to their units. Towards evening the attack was canceled and the British tanks fell back to regroup. Unlike 1940, this time the Italians had proven to be tough and effective opponents. The 22nd Armored Brigade lost at least 25 of its 136 tanks (Italian sources say up to 50). The 132nd Army Division had lost 49 tanks (34 destroyed, 15 damaged), 12 guns and 200 prisoners.

The 7th Armored Brigade pushed forward, pushing the armored vehicles of the Wechmar Combat Group aside. Towards afternoon the British tanks reached the ridge just above the airfield at Sidi Rezegh . The Italian planes and their ground crews had received no warning and were completely taken by surprise when the British appeared. These fired at the airfield, where chaos quickly broke out. Only three aircraft managed to take off, numerous aircraft were destroyed on the ground, another 18 captured and later destroyed. In the evening, advances to the north were repulsed by two battalions of the 361st Infantry Regiment, although the Germans had only a few PAKs . Thanks to the lack of British infantry, the attacks by armored cars and tanks could still be repelled. A similar advance along the road towards Tobruk was repulsed by the Italian 17th Infantry Division "Pavia" under similar auspices. The 7th Support Group, a mixed artillery and infantry unit, was deployed after conquering the airfield to support the 7th Armored Brigade, because unlike Gabr Saleh, the Sidi Rezegh was an essential part of Rommel's defense, making a counter-attack inevitable was.

Rommel initially still refused to take notice of the British attack and was only convinced later that day by reports from Bir el Gubi, Sidi Rezegh and the sighting of British armored vehicles near Bardia that it was indeed a large-scale one British attack acted. In response, he finally sent the 15th Panzer Division south towards Sidi Rezegh in the afternoon and formed Combat Group Stephan from the 5th Panzer Regiment of the 21st Panzer Division, reinforced by twelve 10.5 cm mortars and four 8.8 cm mortars -FlaK . Combat group Stephan was to advance south on Gabr Saleh. The German counterattack expected and hoped for by the British came on the afternoon of the second day.

Kampfgruppe Stephan faced only one unit: The 8th Hussars, part of the 4th Armored Brigade, with an estimated 50 M3 Stuart , which fought against about 120 German tanks (most of them Panzer III and Panzer IV ). The British raced through the German formation, turned and repeated the maneuver. A chaotic battle developed, in which visibility was severely restricted by dust and smoke. At such a short distance, the tanks were almost equal, the normally superior German armor could be penetrated by the weaker British guns in close combat. In the chaos, neither side had a way to effectively control its own troops and the battle wavered to and fro without either side being able to gain the upper hand. The British received reinforcements from the 5th Battalion of the Royal Tank Regiment later that afternoon, without this turning the tide. An hour before sunset, the Germans retreated to be supplied with fuel and ammunition by a supply column. German anti-tank guns held back the British tanks because their guns were too short to be dangerous for the gunners. Due to a lack of British artillery, the British tanks could only watch as their enemies replenished. Until the final nightfall, there were isolated battles, which ended at nightfall. The British withdrew, which allowed German mechanics to repair damaged tanks of their own and destroy broken-down enemy tanks. Both sides claimed victory for themselves and gave inflated numbers for enemy vehicles shot down. On the British side in particular, this led to an unjustified confidence in their own tanks; Gatehouse, the commander of the 4th Armored Brigade, saw the battle proved that his M3 Stuart were on a par with the German Panzer III. This "success report" should have contributed significantly to the fact that Cunningham still did not understand the danger he had brought his army when he spread his armored formations over a large area and three different axes of attack against different targets.

After two days the planned tank battle had still not come about and Cunningham was acting increasingly haphazardly, which confirms his orders from the evening. The 4th Armored Brigade was ordered to fall back to secure the infantry flank. Although he knew of the German attacks there, Cunningham did not reinforce these units, but instead ordered that the 22nd Armored Brigade should join the 7th Armored Brigade and 7th Armored Support Unit at Sidi Reizegh. This should also occupy point 175 - a dominant hill with great tactical value near Sidi Rezegh. The 1st South African Infantry Battalion was to take over the attack against the Ariete Division. At Pienaar's protest, these orders were changed so that the infantry should only watch the Italians. In any case, the 22nd Armored Brigade should not move until it was relieved. God, commander of the 7th Armored Division, established his headquarters near Sidi Reizegh and recognized the weakness of the enemy front line. He therefore informed the corps command that he could possibly advance to Tobruk. Unfortunately, during the night the radio communication of the entire 8th Army broke down, so that no orders could be given.

On the German side, Rommel had decided in the evening to react: Although he considered the infantry of the 90th Africa Light Division strong enough to withstand the British attacks at Sidi Reizegh - just like the Arietedivision in Bir el Gubi, he handed Crüwell over took command of his two armored divisions so that he could attack the British. Crüwell had apparently not seen the reconnaissance results because he saw the focus of the British attacks on Bardia, not Tobruk. He therefore planned to collect combat group Stephan with the 21st Panzer Division and then advance against Sidi Ohmar, destroy the 4th Armored Brigade and then enclose the enemy with the garrisons on the border and destroy them in a classic cauldron battle .

November 20: delays and misjudgments

In the morning around eight o'clock, units of the 90th Infantry Division "Africa" attacked the British at Sidi Reizegh. A first attack was easily repulsed due to a lack of artillery support, but as soon as the Germans deployed heavy French 100 mm booty guns, the attacks became more dangerous. Although the British line held, it was clear that without the extra infantry from the 5th South African Brigade there was no way to take point 175. Cunningham was informed at his headquarters in Fort Maddalena that aerial reconnaissance on the roads behind the German line reported vehicle movements westwards. This was mistakenly interpreted by Cunningham as a more general evacuation, which laid the foundation for his false certainty of victory in the next few days.

Kampfgruppe Stephan fought again against morning with the 8th Hussars and the 5th Royal Tank Regiment. However, they were then ordered to break off the fight and join forces with the rest of the 21st Panzer Division. Gatehouse interpreted this as another “victory” of his superior forces and the British tanks chased the Germans for a few kilometers before they drove back to their starting positions. In the course of the morning Cunningham was presented with intercepted radio messages that both German armored divisions would shortly attack the 4th Armored Brigade. From the XIII. Corps was offered to command the 2nd New Zealand Division, only ten miles away, with the attached 1st Armored Tank Brigade (with heavy infantry tanks ) for reinforcement. This was rejected by Cunningham, true to British doctrine (that infantry are inferior to tanks), which meant that the 4th Armored Brigade would have to fight the ensuing battle alone. From the 22nd Armored Brigade, some smaller units came into the combat area, but they should only arrive after the end of the fighting. In an at least questionable decision, Cunninham did not withdraw the until now clearly underemployed 7th Armored Brigade and 7th Armored Support Group from the Sidi Rezegh airfield, but instead gave them permission to try to break through to Tobruk. In support of this, the 70th Division in Tobruk was supposed to start the outbreak on November 21st and join forces with the 7th Armored Brigade.

The 21st Panzer Division resumed Kampfgruppe Stephan , but now it ran out of fuel, which is why it was paralyzed for at least a day. The 15th Panzer Division reached Sidi Azeiz, but no British were to be found there. This, together with new information from aerial reconnaissance, made Crüwell recognize his mistake: The British marched not on Bardia, but on Tobruk. In response, he planned to strike at Gabr Saleh and then stabbed the British in the back at Sidi Reizegh. Rommel approved of this plan, but demanded that he wait until the morning of November 21, until the 21st Panzer Division had been supplied with fuel, and then attack with both divisions. Crüwell decided for the first time to act against Rommel's instructions and ordered the 15th Panzer Division to attack. The 21st Panzer Division was supposed to catch up during the night.

Around 4:30 p.m., the 135 German tanks of various types of the 15th Panzer Division attacked the 123 M3 Stuarts of the 4th Armored Brigade, which was a clear alarm signal, since the British were technically inferior to the German tanks. In addition, the Germans also had support from infantry, PAK and artillery and thus had a significant advantage. Although the British were positioned on a slight slope with the sun behind them, the Germans attacked. At first, the battle was more or less even, until the Germans got their 8.8 cm flak into position and started shooting down the British tanks one by one. In the absence of artillery, the British were unable to withstand the enemy attack and slowly retreated. At around 6:30 p.m. with waning daylight, the first elements of the 22nd Armored Brigade arrived from the west, but could no longer achieve anything, as the 4th Armored Brigade had already withdrawn towards the south, and were then driven out again by an artillery barrage. The British lost 26 M3 Stuarts and the Germans around 30 tanks, although it is unclear how many of these were repaired.

Crüwell interpreted the German victory as the annihilation of the 4th Armored Brigade, although 97 M3 Stuarts of the 4th Armored Brigade were still intact, which were reinforced during the night by 100 Crusaders of the 22nd Armored Brigade, and put his tanks on the march to advance on Sidi Rezegh and stabbing the units posted there in the back. On the British side, the battle at Cunningham was seen as a British victory, supported by reports that the German armored divisions were withdrawing northwards. 4th and 22nd Armored Brigades were ordered to pursue the Germans the next morning while the code word "Pop" was sent to start the planned breakout from Tobruk the next morning. Problematically, this outbreak was well prepared and trained, but God, the commander of the 7th Armored Division and in Sidi Rezegh, had no direct communication with the units in Tobruk.

The breakout or breakthrough was dependent on the arrival of the 5th South African Infantry Brigade, which did not move until around 5 p.m. and stopped the march completely during the night, as Armstrong - the unit's commander - was concerned that his men would were not experienced enough for a night march.

In the evening, the BBC broadcast a message that the 8th Army had launched an attack with 75,000 men, first to beat the troops of the Axis powers and then to liberate all of North Africa. This broadcast, together with the events of the day, convinced Rommel that a large-scale British offensive was in fact underway, which is why he now postponed the attack on Tobruk.

November 21: Heavy fighting

At around 7 a.m., the German armored divisions began to retreat northwards, being pursued by the Crusaders of the 22nd Armored Brigade, while 4th Armored Brigade was slowed down by refueling their tanks. The German rearguard fought back several attacks with the help of eight-aft and was able to pull away towards Sidi Rezegh as planned. On the British side, the deposition of the Germans was understood as a general retreat and was thus transmitted to Cunningham, with the 22nd and 4th Armored Brigade pursuing the Germans. Encouraged by further apparent successes, Cunningham rejected the XIII. Corps advance. The 2nd New Zealand Division was to advance north on Sidi Azeiz and then northwest towards Sidi Rezegh and Tobruk, while the 4th Indian Division was ordered to destroy the Italian garrisons around Sidi Omar.

Meanwhile, the morale of British defenders in Tobruk had improved significantly thanks to the impending breakout. Pioneers cleared aisles in their own minefields and built five bridges over the anti-tank trenches. At dawn the Polish brigade launched a diversionary attack from inside the siege ring against the Italian 17th division "Pavia". In the southeast, meanwhile, the actual attack was initiated by heavy spear fire from one hundred artillery pieces. Supported by fifty Matildas , elements of the 70th Division attacked and were immediately involved in heavy fighting. Contrary to expectations, the positions of the Axis powers were not only defended by poorly rated Italian units of the 25th "Bologna" Division, but also by German soldiers. The Black Watch Regiment that led the attack alone lost two hundred soldiers and its commanding officer. To fend off the outbreak, Rommel personally brought four 88mm guns from Gambud into battle and used them to ultimately repel the attack. Nonetheless, the British had not only captured 550 German and 527 Italian soldiers, but had also advanced about 3.6 km into the siege lines. However, strong counter-attacks prevented the British from advancing further.

In order to reach the units in Tobruk, an attack had to be made from the south towards El Duda. The 7th Support Group was supposed to carry out this attack, although first sightings of the two German tank divisions were reported from the south. The British attack began quite successfully: after a four-minute barrage, the British armored vehicles advanced quickly under the protection of a smoke screen. In fact, they were so fast that they were caught in the backbone of their own artillery, but fortunately there were no casualties. Some German and Italian positions were overrun without problems, at least until the British vehicles crossed the ridge between Sidi Rezegh and El Duda. German and Italian units had buried themselves here in the back slope, which were also supported by heavy artillery from the Bötcher combat group from the nearest ridge. British infantrymen were dropped from their vehicles and began to return fire. Rifleman John Beeley single-handedly attacked a PAK position and killed the defenders with his Sten Gun until he was fatally wounded himself. For this deed he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross , the highest honor for bravery in the British armed forces. At noon the ridge was in British hands: around 600–700 Axis soldiers had been captured, and around 400 other bodies were counted. In contrast, the British had only lost 84 men.

The 1st Battalion Royal Tank Regiment was now advancing against El Duda, only to be driven away by fire from the same 88mm guns that had been used that morning to stop the Tobruk breakout. Supported by Kampfgruppe Wechmar's armored car, the 88mm guns were able to shoot down the British tanks one after the other as soon as they had crossed the ridge. At the end of these fighting only 28 tanks were operational, about a quarter of their original strength.

At this point, the distribution of troops on both sides was extremely unusual. From north to south several "layers" had formed, alternating between British troops and those of the Axis powers. In the north, British soldiers from Tobruk fought their way towards El Duda, fighting against German and Italian troops who had to defend themselves both north and south. The 7th Armored Division attacked in the direction of Tobruk, while two German armored divisions approached from the south, which in turn were pursued by the 22nd and 4th Armored Brigade.

As a defense against the German armored divisions, Brigadier Davy, responsible for the attack in the direction of Tobruk, had only placed 30 M3 tanks from the 7th Hussars and 2nd Armored Brigade and one artillery battery in the south, probably because he assumed that the Germans, as reported, would be defeated and by the 22nd and 4th Armored Brigades were pursued. The latter was theoretically correct, but in practice the British pursuers had no contact with Germans traveling north. Almost at the same time as the attack in the north began, there was initial contact with the enemy when British tanks were shot at by German PAKs. The PAKs pushed the 2nd Armored Brigade to the west, so that the 7th Hussars had to face the attack more or less alone. Shortly afterwards, the 7th Hussars' thin protective shield was hit by the full force of the German attack, especially since an evasive movement of the British to the east led them directly into the attack of the 21st Panzer Division. The quick German success was supported by the lack of motivation of the 22nd and 4th Armored Brigade, which assumed that they were only pursuing a defeated enemy and therefore did not hurry. 22nd Armored Brigade exchanged shots with German trucks and the like and later claimed to have destroyed 200 German vehicles; which was not reflected in the German archives. However, the appearance of the 22nd Armored Brigade in the rear of the Germans led to a short break in the fight, as the Germans retreated to the northeast in order to ammunition their tanks and to assess the situation. The Hussars were reduced to ten Cruisar tanks in this first battle and thus effectively wiped out.

During this break in the fighting, some South African armored vehicles that had tried to count the German tanks were pursued by German tanks into the area of action of the British anti-tank defense. Five tanks were shot down, several others damaged; all without British losses. This was a clear indication, which was initially overlooked at the time, that enemy tanks had to be separated from their support units in order to be able to fight them effectively.

After supplying their tanks, the Germans attacked again and involved rear units of the 7th Support Group in heavy fighting, while the 2nd Armored Brigade was driven back westwards by a determined attack by parts of the 15th Panzer Division. British 25 pounder guns opened fire and initially drove the Germans away, even if another attack was expected. Calls for help over the radio to Davy's headquarters were rejected by Davys, he accused his people of having fired his people at the 7th Hussars. After air raids by Stukas and artillery fire, the Germans renewed their attacks. Even now Davy did not want to believe his men’s cries for help, but sent five cruiser tanks forward as a security measure. It was only after all of these tanks were shot down without getting within effective range that Davy realized that a German attack was actually underway.

Jock Campbell, the commander of the 7th Support Group, understood the seriousness of the situation much faster: he ordered artillery fire with his 25-pounder guns and carried out a counterattack against about eighty German vehicles with twelve tanks, which led the Germans to attack first cancel. However, this was only a short respite before the Germans resumed their attacks. It is reported that Campbell temporarily coordinated defense efforts on the wreck of an Italian aircraft. Despite the dogged resistance of the British infantry, one by one their guns were silenced during the afternoon. Towards evening the Germans withdrew to their positions in the east of the northern ridge, even if this was more a question of ammunition supplies. The 7th Support Group had prevented the Germans from uniting with their units at El Duda with enormous losses, but was massively weakened. In the evening only 28 of the tanks of the 7th Armored Brigade were still operational.

The 2nd New Zealand Division had reached their destination in Sidi Azeiz more or less as planned (where they captured a German officer while he was taking a bath) and the 7th Indian Division had also taken Sidi Omar as planned, but he was November 21, all in all, a clear victory for the Axis powers. However, Rommel was dissatisfied with the events of the day: He accused Crüwell of not having done enough to prevent the breakout from Tobruk. He therefore ordered Crüwell to continue the attack across the British units. However, Crüwell feared that he would be encircled himself (since he was still being "pursued" by two British tank units) and was not sure whether he would be able to break through directly to El Duda under these circumstances. Therefore he ordered the 15th Panzer Division to evade south and the 21st Panzer Division to bypass the British with a swerve to the northeast and reach El Duda. Under cover of darkness, the Germans withdrew and gave up the battlefield they had won for the third time in three days. This led to renewed certainty of victory in the British command, even if Cunningham was concerned about why the Germans were leaving their favorable position. For reasons unknown, only the good news of the alleged destruction of the Africa Corps reached the 8th Army Headquarters, while the news of the desperate defense of the 7th Support Group was apparently misinterpreted. It was therefore apparently at times assumed that Rommel's armor had been reduced by half. It is possible that the British headquarters simply decided to interpret the losses of the 7th Armored Division of approximately 50% of the tanks in such a way that an equivalent number of enemy tanks had been destroyed. Cunningham saw the lack of connection between Tobruk and British forces as his greatest problem and therefore gave the Chief of Staff of the XIII. Corps to advance orders at its own discretion.

Actions of the XXX. corps

As planned, the Allied formations stationed in the besieged Tobruk - the 70th Division, the Polish Carpathian Brigade and the Czechoslovak Brigade - intervened in the fighting on November 21st. While the two brigades carried out diversionary attacks on the besieging Italian divisions "Bologna", "Brescia" and "Pavia", the 70th Division should break out until Ed Duda advanced and there unite with the South African Division and the 7th Armored Division. The attack of the 70th Division, carried out with great force, surprised the Axis powers and the Tobruk defenders were able to advance about 7 km by the afternoon and take up a number of fortified positions. Nevertheless it soon became clear that the allied troops coming from outside would not be able to get through to them. The airfield of Sidi Rezegh was again the scene of the most violent fighting between the XXX. Corps and the 21st Panzer Division and was finally lost to the Axis powers in the evening of the day.

On November 22nd, Ronald Scobie, the commander of the Tobruk Division, stopped the advance and ordered his troops to widen the previously secured corridor in order to secure their position there. After the XXX. Corps had been pushed back by Sidi Rezegh, the broken garrison initially had no choice but to dig in and hope that the 8th Army would still be able to establish contact with them. The 21st Panzer Division managed to defend its position on the Sidi Rezegh airfield from a counterattack by the 2nd Brigade of the South African Division that day. After this defeat, the 7th Armored Division had to withdraw for good. Of their original 150 tanks, only four were still operational at that time.

On November 23, Rommel attempted to defeat the retreating XXX. Destroy corps in one final assault. The two German armored divisions tried together with the Italian "Ariete" division to encircle the Allied corps in an encircling movement. The renewed, very fierce and associated with great losses on both sides finally led to the destruction of the 2nd Brigade of the South African Division in the so-called “Battle on Sunday of the Dead”. The other Allied formations, however, managed to break through and break away from the pursuers.

Actions of the XIII. corps

While the XXX. Corps had advanced north directly to Tobruk, the XIII. Corps turned east on November 18 and proceeded against the positions of the Axis Powers at Fort Capuzzo , Sollum , the Halfaya Pass and Bardia . Here, too, the fights were extremely tough. The defending Italian division "Savona" proved to be much more disciplined, better equipped and trained than the Italian troops, which the Allies had faced only a year earlier during Operation Compass . The Indian 4th Division was able to take the positions of the Axis powers at Sidi Omar on November 22nd, but suffered great losses of material so that the further advance was initially halted. The attack by the New Zealand Division on Bir Ghirba , however, was repulsed , whereupon it dodged north on November 23. The 5th Brigade of the New Zealand Division finally took position at Fort Capuzzo and Sollum. The 6th Brigade was given the increasing problems of the XXX. Corps in support of this march to the northwest, while the 4th Brigade was to circumvent the fighting at Sidi Rezegh north in an arc in order to advance directly to Tobruk.

Counterattack by the Axis powers

After the XXX. Corps had been forced to retreat and the XIII. Corps was apparently involved in undecided fighting with the Axis frontier garrisons, Rommel decided on November 23 that it was time to counterattack. He let the 21st Panzer Division advance in a south-easterly direction, while the 15th Panzer Division should take action against the suspected enemy troops in front of Bardia. In between, the Italian division "Ariete" should march towards Fort Capuzzo. The XXX. Corps withdrew to the south and west in front of the 21st Panzer Division, while it finally swung in to the east, advanced against the Allied positions at Sidi Omar and suffered heavy losses. The division then advanced south of the border towards Halfaya to support the Italian troops stationed there. The 15th Panzer Division finally arrived in front of Bardia to find that there were no enemy troops worth mentioning in front of the city. The New Zealand 5th Brigade was able to hold its positions at Fort Capuzzo against the “Ariete” division and finally the arriving 21st Panzer Division.

Rommel's counterattack was largely in vain. The allied XXX. Corps had managed to evade its pursuers to the west unobserved and the New Zealand 4th and 6th Brigades had marched unnoticed by the 15th Panzer Division on their way towards Tobruk. At the same time, the armored divisions of the Axis powers were constantly under Allied air attacks, which resulted in continuous losses. The supply situation for the armored divisions was meanwhile precarious. Many tanks had failed due to the fighting and the harsh environmental conditions, and ammunition and fuel were almost exhausted. On November 27th at the latest it became abundantly clear that the counterattack had failed and no decisive victory could be achieved, so that Rommel ordered the retreat to the siege positions in front of Tobruk. On the march back, the 21st Panzer Division met the field headquarters of the 5th Brigade of the New Zealand Division near Sidi Azeiz, which had previously been bypassed, and was finally able to overcome this in tough battles. About 700 New Zealand soldiers were taken prisoner while most of the brigade's vehicles successfully pulled away and withdrew.

The allied XXX. Corps meanwhile used the break to regroup and replace the lost equipment. Since November 25, the fighting at Tobruk has intensified again. There the 4th Brigade of the New Zealand Division had finally reached the city from the east and got into fights with the Italian besiegers. They finally managed to fight their way through to Sidi Rezegh together with the 6th Brigade and bring it back under Allied control. The Tobruk Garrison, the British 70th Division, then resumed their offensive actions and tried again to establish a connection with the relief troops, which finally succeeded on November 27.

The second foray on Tobruk

On November 25th, Claude Auchinleck met Alan Cunningham - the commander of the 8th Army. In the past few days, Cunningham had repeatedly pushed for the entire operation to be aborted, while Auchinleck advocated a more offensive approach. Auchinleck returned to headquarters in Cairo on November 26th and, after consulting his superiors, released Cunningham from his command a day later. In his place, Neil Ritchie took over the 8th Army.

On the way back to Tobruk, the Axis armored divisions got into renewed engagements with the reorganized units of the XXX near Bir el Chleta on November 27th. Corps advancing again on Tobruk. The meanwhile exhausted German and Italian troops, who also suffered from constant air raids by the Royal Air Force, found it increasingly difficult to assert themselves against the Allied units. The heavy fighting between the two sides continued on the next day, with neither the armored units approaching Tobruk nor the units on both sides fighting at the breach through the siege ring succeeded in turning the situation in their own favor. The Italian units alone were able to record a success on November 28 with the capture of a larger field hospital for the New Zealand division.

On November 29th, Rommel decided to withdraw the armored divisions from the XXX. Corps and instead intervene directly in the fighting at the siege ring around Tobruk. His aim was to encircle and destroy the New Zealand units coming from outside. By the evening Sidi Rezegh could be taken again and in the following two days the Axis powers could finally fight their way up to the New Zealand units. At Ed Duda, however, the 15th Panzer Division suffered heavy losses from the British 70th Division stationed there and Rommel finally withdrew to Bir Bu Creimisa . On December 1, the Axis powers pulled together the - albeit still open at Ed Duda - cauldron to destroy the two New Zealand brigades.

The armored formations of the XXX. Corps had hardly intervened in the fighting in the days before. Now they received specific orders to come to the aid of the New Zealanders. However, due to a series of misunderstandings, the Allied commanders on site assumed that the corridor through the siege ring should be abandoned and primarily the withdrawal of the New Zealand division should be covered. This succeeded in heavy fighting in the evening hours and the Allied troops withdrew from Tobruk once more.

Decision before Tobruk

On December 2nd, it seemed to Rommel that the battle for Tobruk had now been finally decided. Although the British 70th Division held its position with Ed Duda, all Allied troops brought in for relief were in retreat for the second time. Rommel's concern was again directed at the border garrisons besieged by the Allies and cut off from supplies. In order to free them, he planned another advance with the remaining troops towards the border area. Two reconnaissance units were sent as advance troops - the Geissler group in the direction of Bardia and the Knabe group in the direction of Fort Capuzzo. Both commands were stopped by the Allies: The Geisler group unexpectedly encountered parts of the New Zealand 5th Brigade and had to withdraw with heavy losses. The advance of the Knabe group was stopped by parts of the Indian 4th Division.

Almost all tanks of the Afrikakorps were in repair or completely broken down, only the Italian "Ariete" division still had battle-ready armored vehicles. In view of this almost complete exhaustion and the failure of an attack on Ed Duda on December 4th, Rommel finally decided to withdraw all forces east of Tobruk, to concentrate his troops in the west of the city and to concentrate entirely on XXX. Allied Corps focus.

The bitter fighting continued until December 6th. The allied Indian division suffered heavy losses when attacking a strategically important hill and had to withdraw almost completely destroyed. The Axis Powers failed to take advantage of the situation because of exhaustion of their own strength. On the evening of December 6th, Hermann Neumann-Silkow, the commander of the 15th Panzer Division , was seriously wounded and died on December 9th in the hospital.

The Gazala Line

Withdrawal of the Axis powers

On December 7th, the Allied 4th Armored Brigade advanced against the 15th Panzer Division, with eleven other German tanks being destroyed and the already heavily decimated stock shrinking further. Since there was now little prospect of Rommel winning against the Allied troops off Tobruk, he decided on the same day to withdraw his troops to Gazala , about 15 km further west . Italian stage associations had already prepared and strengthened their positions there beforehand. The first Axis forces arrived at the new line of defense the following day. On December 10th, the Allies finally had Tobruk and the surrounding area completely under control. The Axis troops remaining in the Sollum-Bardia-Fort Capuzzo area were now finally cut off from all supplies, but initially held their positions.

Attack on the Gazala Line

Neil Ritchie used the days after the relief of Tobruk to reorganize his troops. The severely weakened South African division was the XXX. Corps slammed, which should overwhelm the remaining positions of the Axis powers between Bardia and the Libyan-Egyptian border. The XIII. Corps, the 7th Armored Division as well as the Indian 4th Division and New Zealand 5th Brigade were added to the pending attack on Gazala.

On December 13th, the allied XIII. Corps launched his attack on the Gazala Line and was supported on December 14 by the Polish brigade brought up from Tobruk. The Allies succeeded in taking up some positions and putting the Axis powers under enormous pressure overall, but they were unable to achieve a breakthrough. A German-Italian counterattack on December 15 was able to regain some of the lost positions. The fighting on the Gazala Line was again marked by great severity and led both sides to the brink of complete exhaustion. On December 16, the entire Africa Corps was only able to field eight German and about 30 functional Italian tanks. In view of this, Rommel had his troops withdraw again on the night of December 16, this time to the far western end of the Cyrenaica , to El Agheila . Ritchie's instruction to cut off their route of retreat ultimately failed due to the hesitant action of the Allied commanders on site.

Fall of the remaining garrisons

Until the last skirmishes off Tobruk at the beginning of December, Rommel assumed that he would be able to defeat the Allied troops. Accordingly, no preparations were made to evacuate the remaining garrisons of the Axis powers at Bardia, the Halfaya Pass and in the Sollum area in time. With the necessary retreat to Gazala and the subsequent evacuation of the Cyrenaica, the garrisons were finally cut off. Since they were too weak to make the long way back to western Libya on their own, they had no choice but to dig themselves into the positions and wait for relief.

The allied XXX. Corps set about eliminating the remaining garrisons one by one in the weeks that followed. During the attacks, the Allied High Command took its time to minimize further losses. The garrisons of the Axis powers were largely cut off from supplies anyway, so that their surrender was only a matter of time. The 7,000-strong garrison of Bardia finally capitulated on January 2, 1942 after an attack by the South African division. Sollum fell on January 12th after a brief, violent battle. The 5000 men of the Italian "Savona" division held out the longest at the Halfaya Pass. It was not until January 17th - after all food and especially the water supplies had been used up - that the garrison capitulated. The Allies had thus achieved full control over eastern Libya.

Rommel's counterattack and stalemate

The XIII struck by the previous offensive. Corps had spread widely in the attempt to occupy Cyrenaica. In addition, the supply lines for the Allies became steadily longer, while those of the Axis Powers were shortened. In typical fashion, Rommel turned an advance that had begun on January 21, 1942 and was initially intended only for clarification into a large-scale offensive when the Allied resistance turned out to be weak. On January 28th, the Axis powers retook Benghazi . On February 3, the Africa Corps finally reached Timimi and started the offensive on Tobruk again. On February 4, however, the Allies succeeded in bringing Rommel's renewed advance at Gazala to a halt. Now a stalemate set in, in which both sides dug themselves in and renounced offensive actions in order to rebuild their own strength after the efforts of the previous months.

consequences

After the stalemate at Gazala, there was a break in fighting lasting several months, during which there was only sporadic fighting. Both sides had spent a lot of time in the fighting and were only able to take limited actions. Even if the Allied land gains were manageable, Operation Crusader was an extremely important achievement for the Allies. With their decisive action, Auchinlecks and Ritchie had initially eliminated the threat to Egypt and the strategically important Suez Canal through the axis . Perhaps even more important, however, was the proof that the Africa Corps and with it the German troops could be defeated. Operation Crusader was the first important victory that the Allied troops were able to achieve on land against the Wehrmacht , and in Bardia there was surrender and surrender of a garrison under the command of a German general for the first time during the Second World War. In particular, the allied defenders of Tobruk, who had held the city bitterly against all attacks by the Axis powers for about six months, became an important public symbol of perseverance for the resistance against the Axis powers.

literature

- JAI Agar-Hamilton, Leonard Charles Frederick Turner: The Sidi Rezeg battles, 1941 . This book was prepared by the Union War Histories Section of the Office of the Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa. Oxford University Press, Cape Town 1957, OCLC 25042454 .

- Ian Stanley Ord Playfair , FC Flynn, CJ Molony, TP Gleave: British fortunes reach their lowest ebb: September 1941 to September 1942 . In: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (Ed.): History of the United Kingdom in the Second World War - Military Series (= The Mediterranean and Middle East . Band 3 ). Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London 1960, OCLC 58901476 .

- Barton Maughan: Tobruk and El Alamein (= Australian War Memorial [Hrsg.]: Australia in the war of 1939-1945. Series 1 - Army . Volume 3 ). Australian War Memorial, Canberra 1966, OCLC 933092460 ( gov.au [PDF; accessed December 2, 2018]).

- Gerhard Schreiber , Bernd Stegemann , Detlef Vogel: The Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe. From the "non belligeranza" of Italy to the entry into the war of the United States (= Military History Research Office [Hrsg.]: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 3 ). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-421-06097-5 , The Italian-German warfare in the Mediterranean and in Africa, p. 591-682 .

- Horst Boog , Werner Rahn , Reinhard Stumpf , Bernd Wegner : The global war. The expansion to the world war and the change of initiative. 1941–1943 (= Military History Research Office [Hrsg.]: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 6 ). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1990, ISBN 3-421-06233-1 , Part Five , I. The Beginning of the Second German-Italian Offensive in North Africa and the Battle for Malta, p. 569-594 .

- Mario Montanari: Tobruk (March 1941 – Gennaio 1942) (= Ufficio Storico [Ed.]: Le operazioni in Africa settentrionale . Volume 2 ). Stato maggiore dell'esercito, Roma 1993, OCLC 848349816 , L'Operazione Crusader, p. 419 ff .

- Ken Ford, John White (illustrations): Operation Crusader 1941. Rommel in Retreat (= Osprey Publishing [Hrsg.]: Campaign ). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-1-84603-500-5 .

- Alessandro Massignani, Jack Greene: Rommel's North Africa campaign: September 1940 – November 1942 (= Da Capo Press [Hrsg.]: Great Campaigns ). Da Capo Press, New York 1999, ISBN 978-1-58097-018-1 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ on the losses of the Axis powers cf. Stump p. 587.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 24-26.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 30-38.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 47-50.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 50-56.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 55-60.

- ↑ B. Pitt: The Crucible of War: Auchinleck's Command. The Definitive History of the Desert War. Cassell & Co, 2001, pp. 60-70.

Web links

- bbc.co.uk - Operation Crusader (English)

- Information about the operation ( Memento from January 12, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Information on awm.gov.au (English)

- Russell Bodine : wwii: operation crusader . PageWise Inc , 2002, archived from the original on January 25, 2005 ; accessed on May 7, 2018 (English, original website no longer available).