Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( Italian Africa Orientale Italiana , abbreviated AOI ) was the name of a large contiguous Italian colonial area in the east of Africa , which existed from 1936 to 1941. In addition to the already existing Italian colonies of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland, it also comprised Ethiopia , which had been conquered in the Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-1936). 1940–1941 also included the British territory of British Somaliland, which was occupied by Italy .

Africa Orientale Italiana was disbanded in 1941 after Italy was defeated in the Battle of Gondar . The former Italian colonial areas initially continued to exist.

The non-formal designation "Italian East Africa" for various Italian colonial areas in the Horn of Africa must be distinguished from the actual Africa Orientale Italiana . From 1870 this included smaller branches on the Red Sea , a few years later all of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland were added, and from 1936–1941 also Ethiopia.

Italian colonialism in the Horn of Africa

First possessions

Only 20 years after achieving national unity , Italy decided, despite enormous problems in its own country, to take part in the race for Africa in order to secure its place in the concert of the European powers. Despite these political goals, the first Italian attempts at colonization in East Africa were rather hesitant and improvised.

The first settlement in the region was established in 1870 in the Bay of Assab in what is now Eritrea. The Rubattino shipping company bought a small area there on behalf of the Italian government, but it was soon abandoned for economic and political reasons. It was not until the Depretis government became interested in the small estate again in 1882 and took it over from Rubattino, which officially made it an Italian colony .

The further expansion of colonial rule was achieved through diplomatic agreements with Great Britain . a. wanted to counteract a French expansion in the region ( Djibouti ). In 1885 Italy occupied the Eritrean port city of Massaua and the islands of the Dahlak archipelago in front of it , which led to considerable unrest in the Abyssinian Empire (Ethiopia) because of the sea access.

Conflicts with Ethiopia

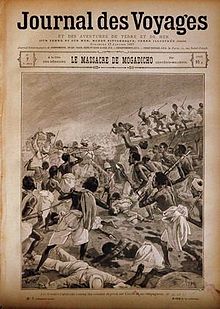

On January 25, 1887, at Saati (20 km west of Massaua), clashes between Italian and Abyssinian troops occurred for the first time . 10,000 Abyssinian soldiers under Ras Alula attacked the fort there, which was defended by two Italian companies and 300 locals. After three hours of fighting, the Abyssinian troops had to withdraw. On January 26, a supply convoy escorted by 500 Italian soldiers set out for Fort Saati, but was caught halfway by Alula's soldiers and completely destroyed in the Battle of Dogali . The few hundred Italians withdrew to the hills near Dogali and fought against the Abyssinian superiority until they ran out of ammunition, then with naked weapons. The Italian commander, Lieutenant Colonel Tommaso De Cristoforis, fell along with 430 other soldiers.

After this incident, Italy sent 15,000 soldiers to Eritrea. They occupied the evacuated Saati and expanded the Italian sphere of influence to Massaua by 1888. The Negus (Emperor) of Abyssinia then started negotiations with Italy. The status quo was agreed . Except for a 6,000 strong protection force in Massaua, Italy withdrew its troops from the region. This protection force under General Antonio Baldissera also set up the first Italian Askari troop in 1888 , which consisted of 1,900 Eritrean soldiers, but was led by Italian officers and NCOs.

Shortly afterwards, a civil war broke out in Abyssinia, in which Italy supported Emperor Menelik II in exchange for territorial compensation. The Treaty of Wichale / Uccialli (May 2, 1889) gave Italy the right to occupy the area between Arafali and Asmara . Article 17 of that treaty was a cunning deception in favor of Italy. The Amharic version of the treaty with equal rights said that the Emperor of Ethiopia could conduct his foreign policy with the support of the Italian government, while the Italian text said that his foreign policy could only be conducted through Italian embassies, which in fact meant the establishment of a protectorate meant. This invalid treaty was ultimately the reason for Ethiopia's declaration of war.

Between 1889 and 1890 the Italians established themselves in the south and north-east of Somalia and steadily expanded their sphere of influence there until 1925. They established the Italian Somaliland colony with Mogadishu (Mogadiscio) as the capital .

Between June 1889 and January 1890, Italian troops occupied Keren , Asmara and even Adwa , which was well beyond the boundaries of the Wichale Treaty. In 1890, however, Adwa was returned to the Negus. In 1893 he terminated the Wichale Treaty because he did not want to bow to the Italian claim to protectorate.

Shortly afterwards, Francesco Crispi took over the post of Prime Minister in Italy . Crispi was a former Italian freedom fighter who, by the time he took over government in 1894, had developed into an anti-parliamentary imperialist who called for a more decisive Italian colonial policy. His governor in Eritrea, the authoritarian General Oreste Baratieri, thought similarly . The tensions between Italy and Abyssinia grew ever more acute.

On December 21, 1893, a 10,000-man force under Amir Ahmed Ali had been defeated near the Italian fortress of Agordat . In the summer of 1894, Baratieri intervened in the Mahdi uprising on the Ethiopian-Sudanese border and captured Kassala on July 17th . In December Baratieri invaded the Ethiopian province of Tigray . On 13./14. or 15./16. January 1895 he defeated the troops of Ras Mengesha Yohannes at Coatit and Senafé , after which he occupied Adigrat , Adua and Tigray's capital Mek'ele . After the Battle of Debra Ailà in October 1895, he then occupied the rest of the province.

Defeat against Ethiopia

Emperor Menelik II took countermeasures: he raised fresh troops all over the country and bought weapons and ammunition in Russia and France . In November 1895 the Negus marched with 150,000 men from Addis Ababa to Tigray, which the Italians had occupied since spring 1895. On the way there, he and 30,000 men attacked an Italian military base on the Amba Alagi . The 2,400 soldiers stationed there defended themselves to the last cartridge under their commander, Major Pietro Toselli, and were then killed (except for 600 men). On January 21, 1896, Menelik retook the fort of Makallé between the Amba Alagi and Adwa after a two-week siege .

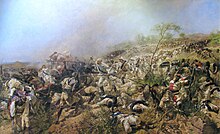

Italy now hastily ordered thrown together reinforcements to Eritrea and Tigray. In February 1896, 10,000 Italian soldiers and 7,000 Askaris faced around 120,000 men from Menelik on the mountain ranges of Saurià (west of Adwa) . In view of the balance of power, the poor local knowledge and the supply problems of his troops, Baratieri initially held back. Because of his caution, he was replaced by the Italian government on February 21, 1896. His successor, General Antonio Baldissera, embarked on February 23 in Brindisi for Massaua. In the meantime, Baratieri decided to approach the Abyssinian camp near Adwa with his troops in order to occupy favorable terrain there. On February 29, at 9:00 p.m., the Italians began this limited advance in four places, but some of their formations got lost during the night. When they were discovered by the Ethiopians the next morning, the Italian leadership no longer had a complete picture of the situation, while isolated Italian formations were gradually being defeated by the enemy. This Ethiopian victory went down in history as the Battle of Adwa . At least 4,900 Italian soldiers and 1,000 askaris fell, 500 Italians and 1,000 askaris were wounded, 1,900 Italians and 800 askaris were taken prisoner. On the Ethiopian side, 7,000 men were killed and 10,000 wounded. Due to other strategic goals, the Negus withdrew and only used Adwa for later negotiations with the Italians.

After this defeat there was a crisis in Italy. Crispi resigned and with him the imperial colonial policy temporarily ended. Baratieri's successor Baldissera reached Massaua on March 4th. He reorganized his troops and brought the Italian prisoners back to Eritrea. On October 26, 1896, both sides signed a peace treaty in which Italy recognized the full independence of Ethiopia.

Strategic importance of the region

In the years after Adwa, not only Italy, but also the other European colonial powers refrained from conquering Ethiopia. In Tunisia and Egypt at the end of the 19th century, France and Great Britain had neglected Italy's interests in the Mediterranean . Although the strategically important British Somaliland was isolated, Great Britain made no move to territorially connect this area on the Red Sea with its other African colonies via the fertile Abyssinian highlands . British colonial policy in these years pursued the goal of implementing the Cape-Cairo Plan and securing the Cairo- India line . a. and the Sudan was subjected to in this way the missing link by Kenya manufacture. With the occupation of Ethiopia, Great Britain would not only have ended the isolation of British Somaliland, but also secured its strategic connections against Italian threats. In the decades before the British conquest of Sudan, France, too, had refrained from combining its strategically important possession of Djibouti with its colonial empire in West and Central Africa. Only the Fascist Italy was in 1935 finally tempted to round off its East African colonies by conquering Ethiopia and to dare the risky attack on the rugged, military highly problematic Abyssinian highlands.

Strategically even more problematic was the fact that Great Britain with Gibraltar , Malta and Suez controlled the Mediterranean Sea and the connection from there to the Red Sea (both via Suez as well as Gibraltar and the Cape of Good Hope ) and thus controlled Italy and especially its East African colonies actually had in hand.

Africa Orientale Italiana

Conquest of Ethiopia

When Benito Mussolini began to conquer Ethiopia in 1935 ( Italian-Ethiopian War , condemned by the League of Nations , the embargo was undermined), he risked a war with Great Britain. While the British government - a National Government under Stanley Baldwin - sent the Home Fleet into the Mediterranean, Mussolini massed troops on the Libyan-Egyptian border to threaten Suez and thus British rule in the Mediterranean. For political reasons, Great Britain finally allowed Mussolini to conquer 330,000 Italian soldiers - the largest non-African army that ever operated in Africa - and 87,000 Askaris from Eritrea and Somalia from Abyssinia , and also to use poison gas bombs in the fighting against the 500,000 men of the Ethiopian emperor began. The civilian population and agricultural areas were also massively bombed with mustard gas , which was a violation of the Geneva Protocol , which Italy also ratified in 1928 . The Italian courage admired by many (including Hitler ) at the time was therefore also connected with Great Britain and not only with Ethiopia. Although Addis Ababa fell, at no time did the Italians control the entire Ethiopian territory.

The decision of the British leadership to allow the Italian invasion put Britain in a similarly problematic position as Italy in the Mediterranean area in the coming years. Italy had a fairly large colonial area in East Africa in 1936, but it was completely isolated from the mother country. However, it posed a certain threat to the British connections between Cairo, Cape Town and India. What was really threatening for Great Britain, however, was that Italy had left Libyan Cyrenaica and East Africa from Sudan, Egypt, the Suez Canal , i.e. all of Northeast Africa and thus British control across the Mediterranean and the sea route to British India .

In 1940 it became clear that Italy's insufficiently motorized and armored troops in the North African desert war posed no real threat to British-controlled Egypt and the Suez Canal. In East Africa, too, the isolated Italian units could ultimately hardly hope for a strategic success (Sudan, Libya , Egypt) against the Commonwealth troops coming from India and other parts of the Empire , especially not if there was no simultaneous advance eastwards in North Africa and southeast came.

Italy was able to achieve certain successes against Great Britain in East Africa in 1940 (occupation of British Somaliland in a short time). This and the subsequent struggle against the Allied counterattack, which was sometimes boldly conducted at various points, cannot hide the sometimes catastrophic preparation, planning and conduct of the war by the fascist regime.

Second World War

Mainly because of the uprisings against fascist rule in Ethiopia, considerable contingents of Italian troops were stationed there (cf. Italian war crimes in Africa ). In 1937, instead of the planned 100,000 soldiers, 135,000 Italian soldiers and 120,000 colonial troops were on Ethiopian soil, in May 1940 there were then a total of 285,000 soldiers, 85,000 of them Italians (a little later then 91,000). These troops should (and had to) fight on their own in the event of war. Their commander, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani , in December 1937 a. a. three tank brigades (practically the entire Italian armored force at the time ) for the effective defense of the area, which was rejected on the grounds that it should primarily take care of internal security. Only in May 1940 did 50 inferior tanks (11 tons ( Fiat M11 / 39 ) or 5 tons) and some artillery pieces arrive . Due to a lack of motorization, the numerically strong Italian units could hardly move in an appropriate manner in the enormous operating rooms. The constant uprisings also bound a large part of these associations in Ethiopia. The supply situation was far from enabling "autonomous" warfare (planned duration: one year). The Italians and their Eritreans were just able to put down rebellions with these associations, but they could not wage a modern war against a great power. Italian initial successes were favored by the fact that Great Britain initially had very few troops stationed in the region (almost 20,000). In contrast to the Italians, however, these could be continuously strengthened (+60,000) and supplied.

After Mussolini's declaration of war on June 10, 1940, the Italians first conquered the strategically important Kassala in the south-east of Sudan and a few smaller, favorable places on the borders with British Kenya ( Moyale ) and French Djibouti. Although it was feared that Djibouti , which is part of Vichy France , could be occupied by the British as a future base of operations, an attack was waived in accordance with the treaty. British Somaliland, on the other hand, was the target of a first major Italian attack from August 3, 1940. The few battalions (including a battalion of the Scottish Black Watch Regiment) of British General Arthur Reginald Chater tried to build an effective defense on a mountain range 60 km behind the border, but failed at Tug Argan after four days of heavy fighting against the 26 battalions of the Italian General Guglielmo Nasi . After the occupation of British Somaliland, the Commonwealth had lost 250 men, the Italians and their Askaris 205.

Six months later, in February 1941, Great Britain launched a counter-offensive from Kenya in the direction of Italian Somaliland. The Italian resistance to the British advance was initially sporadic and ineffective, later it collapsed completely due to the lack of motorization and air support. General Cunningham's motorized troops continued to advance into the Ethiopian lowlands ( Ogaden ) after the occupation of Mogadishu .

At the same time, British troops under Lieutenant-General William Platt attacked from Sudan, placing Abyssinia in strategic pincers. The Italians withdrew to isolated and more easily defended areas, also because the British troops were very effectively supported by local rebels. It came u. a. also to the massacre of Dire Dawa (80 km northwest of Harar ), where the complete extermination of the Italian population could only be prevented by an intervention of the British general Harry Edward de Robillard Wetherall (in the further course the Italians asked the British troops several times to visit certain areas occupy quickly to prevent further massacres of the Italian civilian population). At the end of March 1941, the Italian viceroy, Amadeus III. of Savoy-Aosta , another Italian resistance near Addis Ababa impossible. He withdrew with 7,000 men to the Amba Alagi , where as early as 1895 the 2,400 men of Major Pietro Toselli had fought to the last cartridge . Only now did the Italians begin to resist resolutely. At Keren , the British advance to Massaua failed for two months due to resistance from the troops of the Italian general Nicolangelo Carnimeo. Of El Alamein ( Parachute Division "Folgore" and tank division "Ariete" ) and Enfidaville ( Infantry Division "Trieste" ) apart, the Italian troops in World War II fought anywhere so determined and disciplined against the troops of the Empire as in Keren, on the Amba Alagi and around Gondar . Overall, however, the resolute Italian resistance was limited to a few places and people ( Amedeo Guillet ); in many other areas the Italian officers and their troops showed a comparatively low level of fighting spirit, which in some cases even led to the viceroy being refused orders (as in the case of the commanded Defense of the mountain passes at Harar and other key positions). The occasional decisive Italian resistance ended in November 1941 with the fall of Gondar .

See also

literature

- Asfa-Wossen Asserate , Aram Mattioli (ed.): The first fascist war of annihilation. The Italian aggression against Ethiopia 1935–1941 (= Italy in modern times. Volume 13). SH-Verlag, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-89498-162-8 (conference, University of Lucerne, October 3, 2005: The Abyssinian War (1935–1941) in history and memory ).

- Matteo Dominioni: Lo sfascio dell'Impero. Gli italiani in Etiopia 1936–1941 (= Quadrante. Volume 143). Prefazione di Angelo Del Boca. Laterza, Rome et al. 2008, ISBN 978-88-420-8533-1 .

- Aram Mattioli: Experimental field of violence. The Abyssinian War and its international significance 1935–1941 (= culture - philosophy - history. Volume 3). With a foreword by Angelo Del Boca. Orell Füssli, Zurich 2005, ISBN 3-280-06062-1 .

- Arnaldo Mauri: Il mercato del credito in Etiopia (= Istituto di Economia Aziendale dell'Università Commerciale "L. Bocconi". 5, 20, ZDB -ID 1421295-x ). Giuffrè, Milan 1967.

- Alberto Rovighi: Le Operazioni in Africa Orientale (July 1940 - November 1941). 2 volumes. Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore dell'Esercito, Rome 1988.

- Gerhard Schreiber : The political and military development in the Mediterranean area 1939/40. In: Military Research Office (ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War. Volume 3: Gerhard Schreiber, Bernd Stegmann, Detlef Vogel: The Mediterranean and Southeastern Europe. From the "non belligeranza" of Italy to the entry of the United States into the war. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-421-06097-5 , pp. 4–414.

- Gerald Steinacher (Ed.): Between Duce, Führer and Negus. South Tyrol and the Abyssinian War 1935–1941 (= publications of the South Tyrolean Provincial Archives. Volume 22). Athesia, Bozen 2006, ISBN 88-8266-399-X .

- Michael Thöndl : The Abyssinian War and the Totalitarian Potential of Italian Fascism in Italian East Africa (1935–1941). In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries. 87, 2007, ISSN 0079-9068 , pp. 402-419.

- Michael Thöndl: Mussolini's East African Empire in the Records and Reports of the German Consulate General in Addis Ababa (1936–1941). In: Sources and research from Italian archives and libraries. 88, 2009, pp. 449-488.

Individual evidence

- ^ Giampaolo Calchi Novati: Africa Orientale Italiana. In: Siegbert Uhlig (Ed.): Encyclopaedia Aethiopica . Volume 1: A-C. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2003, ISBN 3-447-04746-1 , pp. 129-133 / 134.

- ^ Giampaolo Calchi Novati: Italian Somaliland. In: Siegbert Uhlig (Ed.): Encyclopaedia Aethiopica . Volume 3: He-N. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05607-6 , pp. 224-226.

- ^ Charles Henry Alexandrowicz: The European-African Confrontation. A Study in Treaty Making. Sijthoff, Leiden 1973, ISBN 90-286-0303-4 , p. 72 ff.

- ↑ Hatem Elliesie: Amharic as a diplomatic language in international treaty law . In: Aethiopica. International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies. Volume 11, 2008, ISSN 1430-1938 , pp. 235-244, online .

- ↑ Wolfgang Altgeld , Rudolf Lill : Little Italian History (= series of publications of the Federal Agency for Political Education. Volume 530). Federal Agency for Political Education, Bonn 2005, ISBN 3-89331-655-8 , p. 333 ff.