Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946)

|

Kingdom of Italy Regno d'Italia 1861–1946 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Motto | FERT FERT FERT | ||||

| Constitution |

State constitution of the Kingdom of Italy (Statuto Albertino) |

||||

| Official language | Italian | ||||

| Capital |

Turin (1861–1864) Florence (1864–1871) Rome (1871–1946) |

||||

| Form of government | kingdom | ||||

| Government system |

Parliamentary monarchy (1861–1925 and 1943–1946) monarchical - fascist one-party dictatorship (1925–1943) |

||||

| Head of state |

King : Viktor Emanuel II. (1861–1878) Umberto I (1878–1900) Viktor Emanuel III. (1900–1946) Umberto II. (1946) |

||||

| Head of government | Prime Minister see President of the Council of Ministers |

||||

| area | 310,196 km² (1936) | ||||

| Residents | 42,994,000 (1936) | ||||

| Population density | 138.6 inhabitants / km² (1936) | ||||

| currency | Italian lira | ||||

| founding | March 17, 1861 ( Victor Emmanuel II proclaimed King of Italy) |

||||

| resolution | June 3, 1946 (referendum on the form of government) |

||||

| National anthem | Marcia Reale | ||||

| Time zone | CET | ||||

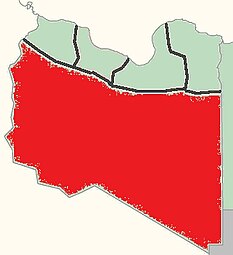

Territories and colonies of the Kingdom of Italy 1941:

|

|||||

The Kingdom of Italy ( Italian Regno d'Italia ) was a state in southern Europe , which existed from 1861 to 1946 on the territory of what is now the Italian Republic and parts of its neighboring states. During this period, Italy was (formally during the period of Italian fascism 1922-1943), a centrally organized, the monarchical principle aligned constitutionally - parliamentary monarchy .

The kingdom was founded in 1861 in the course of the Risorgimento movements , in the final phase of which with the proclamation of the Sardinian King Victor Emmanuel II as King of Italy on March 17, 1861 in Turin, the first modern Italian nation-state was established under the rule of the House of Savoy . In 1866 he declared war on the Austrian Empire and acquired Veneto with Friuli . In 1871 the Papal States followed with Rome, which ended the Italian Wars of Independence .

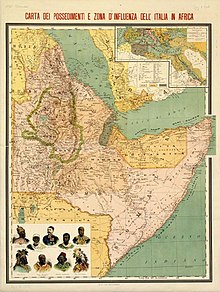

During a long liberal political phase increased the Kingdom of Italy under King I. Umberto 1878 to great power and took part in the 1880s on the colonial scramble for Africa , where there are several colonial wars in East Africa and from 1911 to 1912 to the later Italian Libya a Waged war against the Ottoman Empire . In 1882 the alliance of the Triple Alliance was concluded with the German Empire and Austria-Hungary . At the beginning of the 20th century Italy had changed from an agricultural state to, together with France and Austria-Hungary, the most important industrial country in the Mediterranean region . It came under Umberto's successor, Viktor Emanuel III. from 1900 in the large industrial centers of northern Italy for the rise of organized workers and the bourgeoisie as well as mass associations and parties. In the south , on the other hand, the economic upturn was slow to arrive.

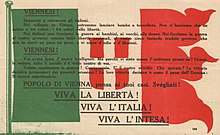

With the beginning of World War I in 1914, Italy declared its neutrality . After the London Treaty of 1915 , in which extensive territorial concessions were agreed, the war entered the war on the side of the Entente in the same year . After the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in 1918, which contributed significantly to the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire, the kingdom was one of the main victorious powers and had a permanent seat in the League of Nations .

The end of the world war triggered a serious national crisis in 1919. In this, the National Fascist Party under Benito Mussolini took power with the March on Rome in 1922 and gradually undermined democracy by 1926. The Fascist regime began after a period of following the Western democracies and the internal consolidation, by an enormous economic recovery and ongoing since 1923 reconquest of Libya was marked, an aggressive foreign policy. After overcoming the global economic crisis of 1929, the Italian conquest of Ethiopia began in 1935 , to which the West responded with economic sanctions. Italy was internationally isolated.

From 1936 Italy turned to Nazi Germany . This in turn supported the desired Italian supremacy in the Mediterranean and on the Balkan Peninsula . In 1936 the later alliance of the Axis powers was founded and until 1939 both states intervened together in the Spanish civil war in favor of the putschists under Francisco Franco . This process went hand in hand with an increasing ideologization and radicalization of the regime. In 1937 the Italian Racial Laws for the colonies were enacted, which mainly disenfranchised the indigenous population in the colonies, and the forced Italianization of the ethnic minorities intensified. In 1938 the anti-Semitic racial laws followed .

After the annexation of Austria and the Munich Agreement in 1938, Italian troops occupied Albania in 1939 . Italy formed an important member of the Axis powers during World War II. After initial successes, the successive defeats in East Africa, North Africa and the Soviet Union from the summer of 1941 onwards led to a loss of support for the fascist regime and the monarchy among the population. The Allied landing on Sicily in 1943 brought about the overthrow of the fascist dictatorship in July and Italy left the Axis alliance in the Cassibile armistice . On October 13, 1943, the Allies entered the war again . The Wehrmacht then occupied the north of the country and established a puppet government with the Italian Social Republic , which existed under the formal leadership of the old fascist regime until the spring of 1945.

After the end of the Second World War, the Italian monarchy had to accept the loss of its colonial empire and the possessions in Istria and Dalmatia by Yugoslavia and overcome an economic crisis, which was caused by a significant decline in industrial production, food shortages and the destruction of large parts of the infrastructure in northern and northern Germany Central Italy had been raised. In May 1946 Viktor Emanuel III thanked him. in favor of his son Umberto II . This ruled only 40 days. On June 2, 1946, the monarchy was abolished after a referendum and the Italian Republic was proclaimed, which in 1947 gave up all claims to Istria and the former colonies, in 1948 legally abolished the Italian nobility and sent the Savoyans into exile.

Unification process (1848–1871)

The establishment of the Kingdom of Italy was the result of the combined efforts of Italian nationalists and monarchists loyal to the House of Savoy to establish a united kingdom on the Apennine Peninsula .

After the revolution of 1848/49 , the revolutionaries Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini initially established themselves as leaders of the Italian unification movement . In the world, Garibaldi was known mainly for his extremely loyal followers and his military achievements in South America . He strove for the unification of southern Italy into a constitutional republic , but this was in contrast to the northern Italian monarchy of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Sardinia , which had been the last important and militarily powerful Italian state after the Congress of Vienna . The Sardinian government under the leadership of Count Camillo Benso von Cavour also had ambitions to achieve a unified Italian state. Although the monarchy had no political, cultural or historical connection with Rome , it was nonetheless considered by Cavour to be the natural capital of Italy.

Compared to Garibaldi, the Kingdom of Sardinia had an important power-political advantage with the elimination of the influence of the Austrian Empire in the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859 and the annexation of Lombardy to the Austrian crown land of Lombardy-Venetia . In addition, Cavour had secured his country with alliances with Great Britain and France , which should serve to improve the possibilities of the unification of Italy. In the Crimean War from 1853 to 1853, Sardinia underpinned this with the intervention of its own 15,000-man expeditionary force in favor of France and Great Britain against the Russian Empire . In addition, most of the insurgents and revolutionaries in the Italian states such as the Grand Duchy of Tuscany , the Duchy of Modena and the Duchy of Parma were loyal to Sardinia. In order to strengthen the foreign policy alliance, Sardinia ceded Savoy and the county of Nice in the Treaty of Turin in 1860 as a thank you to France , but this met with resistance in Cavour's government.

In the spring of 1860 Garibaldi's revolutionary movement gained strength in southern Italy. His irregulars (" Zug der Tausend ") succeeded in completely occupying the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in February 1861 , and they forced Francis II to flee. The Sardinian government wanted then the peripheral regions of the Papal States occupy, to forestall the revolutionaries. The project led to the annexation of some smaller peripheral areas. So Rome and its surroundings remained under the control of Pope Pius IX. Despite the setback and the ideological differences between the Sardinian royal family and Garibaldi, the latter gave in and resigned from his claim to leadership. Sardinia then occupied Umbria and the Marches , and southern Italy joined the north. The Sardinian Parliament then proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy on February 18, 1861 (officially proclaimed on March 17, 1861). On March 17, 1861, King Victor Emanuel II of Sardinia-Piedmont from the House of Savoy was proclaimed King of Italy in the first Italian parliament throughout Italy .

After the unification of Italy there was renewed tension between monarchists and republicans. In April 1861, Garibaldi called on Cavour to resign in the Chamber of Deputies of the Italian Parliament . The reason for this was Cavour's uncompromising action against republican guerrillas in the brigands war in the south. When Cavour died on June 6, 1861, several political camps formed among his successors in the ensuing political instability. Garibaldi and the Republicans became increasingly revolutionary with their demands. Garibaldi's arrest after a skirmish between royal Italian troops and his supporters on August 29, 1862 on Aspromonte was the cause of worldwide controversy.

In 1866, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck offered King Viktor Emmanuel II an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia ( Prussian-Italian Alliance Agreement ). Italy accepted it and on June 20, 1866 declared war on the Austrian Empire in the Third Italian War of Independence . However, the new Royal Italian Army and Navy fared badly in this uncoordinated parallel war with Prussia. The attempts to conquer Veneto and Friuli failed. But since Prussia won its war against Austria, Italy was able to occupy the two areas and annex them on July 25, 1866. The main obstacle to Italian unity remained Rome.

In July 1870 the Franco-Prussian War broke out between Prussia and France . To keep the large and powerful Prussian army in check, the French Emperor Napoleon III. withdraw the French troops in Rome. Victor Emanuel II then had Rome attacked from September 11, 1870. On September 20, 1870, Rome and the rest of the Papal States were taken (so-called "Breccia di Porta Pia"). With the exception of the troops of the papal Swiss Guard, the company met with little resistance. With the proclamation of Rome as the capital on January 26, 1871 and the solemn entry of the king, the Italian unification ended. After that, the government moved its seat from Florence to the new capital.

Although the unification of the Kingdom of Italy was widely accepted by the Italians by 1871 and legitimized by referendums in the individual regions, the conditions for the construction of the new state were poor. The economic situation was catastrophic. There was no industry or transport, and extreme poverty (“mezzogiorno”) prevailed in the south . Because of the high illiteracy rate and the rule that the right to vote was linked to a certain income limit, only 2% of the total population had the right to vote in 1861. In the first parliamentary elections in January 1861, out of 26 million people, only 419,938 people could vote. In the end, the valid votes were reduced to 170,567 people, of whom around 70,000 were state employees, 85 princes, dukes and margraves, 28 officers, 78 lawyers, doctors and engineers.

The new state adopted the Sardinian-Piedmontese constitution of 1848, which established a constitutional-parliamentary monarchy. Italy received a very centralized administration and, like France, was divided into provinces .

After the conquest of Rome in 1870, relations between the Kingdom of Italy and the Vatican were at a low point for the next 60 years. The popes called themselves "prisoners in the Vatican". The Catholic Church often protested against actions and steps of the secular and partly anti-clerical influenced various Italian governments and refused any cooperation with emissaries of the king or the Italian state. It was not until 1929 that the so-called “ Roman question ” could be resolved with the signing of the Lateran Treaty .

Structure of the state

The Kingdom of Italy took over the state structures of the predecessor state of Sardinia in many areas , which were gradually transferred to the entire country. It was not until the late 1870s that these structures were cautiously abandoned, which (for example, by maintaining the constitution of 1848) essentially remained in place until the end of the monarchy in 1946.

A major challenge for the Prime Ministers of the new state was the integration of the political and administrative systems of the seven different predecessor states into a unified policy and the creation of a centralized, unified state based on the French model. The predecessor states were proud of their own historical patterns and there was a pronounced regionalism . The social, societal, economic and political predecessor structures could only be adapted with great difficulty. Prime Minister Cavour began planning a unification of the state before 1861, but died before it was fully developed. The easiest thing to do was to harmonize the administrative structure of the Italian regions . Practically all of them followed the Napoleonic administrative pattern of the first French Empire . The second challenge was to develop a stable and vibrant parliamentary system . Cavour and most of the Liberals admired the British system of parliamentary monarchy and carried it over to Italian politics. The harmonization of the Royal Army and Navy was much more complicated, largely because the systems of recruiting soldiers and selecting and promoting officers differed widely among states. This disorganization also led to the defeat of the Italian navy and army in the war of 1866 . The Sardinian military system could therefore only slowly be transferred to the Italian regions over several decades and the former predecessor armies integrated into the new royal army. Also in the education system and in the area of law there were only a few connecting elements.

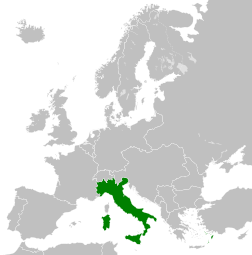

territory

The Kingdom of Italy comprised the entire territory of what is now Italy and parts of its direct and indirect neighboring states France , Greece , Albania , Montenegro , Croatia , Slovenia , Tunisia and Libya . In the course of its history the country had several changing neighboring countries due to its European colonial territories: France in the west and northwest (1861-1946), Switzerland in the north (1861-1946), Austria-Hungary in the northeast (1861-1918), Austria in the North (1918–1938 and 1945–1946) the German Reich in the north (1938–1945), Yugoslavia in the east (1918–1941 and 1945–1946), Croatia , Serbia and Montenegro in the east (1941–1945), Greece in the southeast (1939–1945), Bulgaria in the southeast (1941–1945), French Tunisia in the southwest (1939–1942 and de jure 1943–1946), Egypt (1939–1943 and de jure 1943–1946) and French Algeria (1939 -1943).

The kingdom's territorial development continued until 1870 during the Italian Wars of Independence and the Risorgimento . This was followed by a long period of peace with only minor territorial acquisitions in Europe (1912 annexation of the Dodecanese islands, on October 30, 1914 occupation of the Albanian island of Sazan ). During this period, the Italian state did not own the Italian-populated areas of Trieste and Trentino - South Tyrol , both of which are now part of Italy. In irredentism , nationalists demanded additional areas to complete the unification of all Italians within Italy. The connection of Istria , Corsica , Nice , Savoy , Monaco , the Swiss cantons of Ticino , Wallis , Graubünden and Geneva , Dalmatia , Malta , San Marino , Montenegro and Albania was called for, which led to conflicts with neighboring countries, especially France , Austria-Hungary and Serbia (see also Greater Serbia ).

In the London Treaty of 1915 , France, Great Britain and the Russian Empire promised Italy Trentino, Tyrol to Brenner , Trieste, Gorizia and Gradisca d'Isonzo , Istria and northern Dalmatia (excluding Fiume ) and Albania. After the First World War , Italy was able to secure Trentino and South Tyrol from the territory of the collapsed Habsburg Monarchy in 1919 , plus the coastal region with parts of the Duchy of Carniola and some Dalmatian islands with the city of Zara . The claims to northern Dalmatia and most of the Dalmatian islands, which Italy had also been promised, the kingdom had in the Peace Treaty of Versailles 1919 under pressure from US President Woodrow Wilson , who propagated the right of self-determination of the peoples and on a compromise between Italy and the new kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes gave up. During the time of fascism a new phase of territorial expansion began with the aim of establishing a Greater Italy ( Italia Imperiale ). In 1924 with the Treaty of Rome Fiume, in 1939 after the Riconquista della Libia, northern Libya and Albania were annexed and declared an integral part of the Italian nation. In the course of the Second World War , parts of south-eastern France followed (see western campaign ), in 1941 most of Slovenia (summarized in the Province of Ljubljana (Italian Provincia di Lubiana )) and Dalmatia (summarized in the Governorate of Dalmatia (Italian Governatorato di Dalmazia )) and the Greek Ionian Islands (Italian Isole Ionie ) and 1942 Tunisia (combined with Libya to form the fourth coast (Italian Quarta Sponda )). After World War II, the Kingdom of Italy had to surrender all of these territories and was re-established de jure within the 1938 borders, with parts of its territory under the partial or full control of Greece, Yugoslavia, France and Great Britain.

The Kingdom of Italy also owned several non-European colonies , protectorates , puppet states and militarily occupied areas such as Italian Eritrea (gradually occupied from 1882, merged into a colony in 1890), Italian Somaliland (gradually occupied from 1888, initially an indirect rule), Italian Libya (1911 by the Ottoman Empire acquired and united in 1934 after the reconquest of Libya), Antalya and region (1919-1923 occupied ), Ethiopia ( occupied from 1936 to 1941 and part of Italian East Africa ), Albania (1917-1920 and since 1925 de facto Italian protectorate (see Albanian Kingdom ), 1939 occupied ), British Somaliland (1940 occupied until 1941 and annexed to Italian East Africa), the Hellenic State (1941-1943 occupied , de facto protectorate (see history of Greece ) the Independent State of Croatia (Italian Stato Indipendente di Croazia ) (Italian protectorate from 1941 to 1 943, along with Hitler's Germany occupied ), Kosovo part of Italian-Albania from 1941), the ( Independent State of Montenegro (Italian Stato Indipendente del Montenegro occupied) 1941-1943, Protectorate) and a small 46-hectare concession in the Chinese city of Tianjin .

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1946 and in the subsequent peace treaty of February 10, 1947, the Italian Republic had to renounce all colonies and protectorates, with the exception of Italian Somaliland, which was under Italian control as a UN trust territory until 1960 and then became part of the state of Somalia .

- Territorial development of the Kingdom of Italy in Europe

1943–1945 (light green Italian Social Republic )

- Territorial development of the Italian colonial empire

Political system

The Kingdom of Italy was theoretically a constitutional monarchy . The executive power belonged to the monarch and he alone appointed and dismissed all ministers and they were theoretically responsible to him alone. In practice, however, no Italian government has been in office without the support of Parliament . From 1876/78 at the latest, the Kingdom of Italy was de facto a parliamentary monarchy based on the British model.

The right to vote , initially restricted to selected citizens, was gradually expanded. In 1911, the government of Giovanni Giolitti introduced universal suffrage for male citizens. At the beginning of the 20th century, many observers saw Italy as a modern and largely stable parliamentary democracy compared to other countries.

Between 1925 and 1943 Italy was virtually de jure a fascist dictatorship , as the constitution remained in force officially without being changed by the fascists, however, during the fascist period from 1922 to 1943, many laws were passed that were constitutional .

Constitution

The constitution of the kingdom, officially the state constitution of the kingdom of Italy (Italian Legge organica del Regno d'Italia ), was based on the fundamental statute of March 4, 1848 , the constitution given to the kingdom of Sardinia by King Charles Albert . According to this, the form of government was the representative monarchical one. Individual freedom was guaranteed; the apartment was inviolable; the press was free ; the right of assembly was recognized. Every citizen had the right to petition Parliament.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s the constitution was changed a few times and its interpretation was liberalized so that the king hardly interfered in daily politics and all governments needed the support of parliament. However, the monarch was still regarded as a “guarantor of stability and continuity” and he still had a strong position in foreign and military policy and in times of crisis . The constitution remained formally in force during the fascist rule and was only replaced by the current constitution of the Italian Republic in 1948 .

Monarchs

The King of Italy held state authority, but could only exercise the right to legislate in association with the national parliament. According to Salian law, the throne was inherited from the male line of the royal house of Savoy . The king committed himself to the Roman Catholic Church with his house . He was awarded the age of 18 years of age and placed on his throne in the presence of both chambers an oath to the Constitution from. According to the law of March 17, 1861, his title was: " By God's grace and by the will of the nation King of Italy and King of Albania (only from 1939–1943) and Emperor of Ethiopia (only from 1936–1943)”. He bestowed the five orders of knighthood of Savoy and exercised constitutional sovereignty. He was in command of land, sea and air power; He declared wars, concluded peace, alliance, trade and other treaties, of which only those which involved a financial burden or a change in the area required the approval of the chambers to be effective. The king appointed to all state offices, sanctioned and promulgated the laws, which as well as the government acts had to be countersigned by the responsible ministers , and issued the decrees and regulations necessary for the implementation of the laws . The judiciary was administered in his name; he alone was entitled to the pardon and the mitigation of sentences.

| # | image | Name (life data) |

Domination | coat of arms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginning | The End | ||||

| 1 |

|

Victor Emanuel II (Father of the Fatherland) (1820–1878) |

March 17, 1861 | January 9, 1878 |

|

| 2 |

|

Umberto I (the good) (1844–1900) |

January 9, 1878 | July 29, 1900 |

|

| 3 |

|

Victor Emmanuel III (the soldier king) (1869–1947) |

July 29, 1900 | May 9, 1946 |

|

| 4th |

|

Umberto II (the May King) (1904–1983) |

May 9, 1946 | June 12, 1946 |

|

Government and ministries

The executive power was exercised by the king through the responsible ministers, who met in the Council of Ministers (unofficially in use Royal Italian Government (ital. Gouverno italiano reale)). In addition to this, there was a State Council , which had consultative powers and decided on conflicts of competence between administrative authorities and courts as well as on disputes between the state and its creditors. It consisted of a President, three Section Presidents, 24 Councilors of State and the service staff and was appointed by the King on the proposal of the Council of Ministers. The highest state administration was divided among the following ministries, with the seat in Rome:

- the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (with the Council for Diplomatic Disputes);

- the Ministry of the Interior (with the Senior Medical Council);

- the Ministry of Grace, Justice and Culture ;

- the Ministry of Finance and Treasury ;

- the War Ministry (the committees for the general staff, the line arms, the royal carbines, for artillery and genius, for the military medical service and the supreme war and naval tribunal are subordinate to it);

- the Navy Ministry (with the Obermarinerat);

- the Ministry of Public Education (with the Senior Education Council);

- the Ministry of Public Works (with the Upper Public Works Council and the Railway Council);

- the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade (with the mountain ridge and the Central Statistical Giunta);

- the Ministry of Colonies (since 1937 Ministry of Italian Africa);

- the Ministry for the Liberated Areas (for the areas occupied and annexed after the First World War );

- the Ministry of Transport ;

- the Ministry of Aviation;

- the Ministry of Education ;

- the Ministry of Post and Telegraph;

- the Ministry of Labor ;

- the Ministry of Agriculture

Due to the war, a number of other short-lived ministries were created during the First and Second World Wars .

The Court of Auditors of the Kingdom had an independent position .

houses of Parliament

The representative body of the Kingdom of Italy consisted of two chambers, the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies . The Senate consisted of the royal princes and members who were appointed by the king for life from certain categories of citizens (holders of certain offices and dignities, men and persons who earned 3000 lire annually in direct taxes ) and were at least 40 years old were appointed. The second chamber was the Chamber of Deputies and had 508 members who were directly elected in 135 constituencies (2–5 members in each district) through the list scrutinium for a period of five years. Voters were all Italians who enjoyed civil and political rights, had reached the age of 21, could read and write, and paid 20 lire direct taxes or were entitled to vote by virtue of certain personal status or qualifications. The women's suffrage was introduced 1946th All voters over 30 years of age were eligible as deputies. Pastoral care chaplains, state officials (with the exception of ministers, general secretaries, senior officers, university professors, but even these only in a maximum number of 40), Sindaci , provincial deputies and persons who received salaries or remuneration from subsidized companies were not eligible . The King called the Chambers together every year; the meetings were public . The Presidium of the Senate was appointed by the King, that of the Chamber of Deputies was elected by the King. The latter had ministerial indictment rights , in which case the Senate acted as the court. The provinces had self-government, the exercise of which was entrusted to the provincial council elected by the local electors for five years and the provincial deputation appointed by it. The municipal organs were the municipal council elected for five years, the Munizipalgiunta elected from among the municipal council and the Sindaco, the head of the municipal administration.

After a short multinominal experiment under Prime Minister Agostino Depretis in the elections in 1882, large, regional and multi-sensory constituencies were introduced after the First World War. The socialists won a majority in the 1919 and 1921 elections but were unable to run the government. In November 1923, Mussolini replaced this system with the Acerbo Act , an electoral reform that gave the party with the highest vote two-thirds of the seats in parliament, provided it received at least 25% of the vote.

- Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy

Political parties

From the founding of the state up to the 1890s, Italy was dominated by the two most important groups of the historical right (ital. Destra storica ) and left (ital. Sinistra storica ). These did not form actual political parties, but rather collective movements for a group of prominent politicians with similar political ideas. These two factions were considered to be the two poles of the beginning liberal era. To the left of the spectrum were the republicans (ital. Estrema Sinistra Storica ), who represented the extreme parliamentary left until 1892 and only organized into a real party in 1895.

With the establishment of the Socialist Party (Italian Partito Socialista ) in 1892, the Kingdom of Italy had a remarkable experience, rich in political and democratic practices, from 1890 to 1946.

The political landscape was dominated at the turn of the century by three political groups, the Liberals, the Republicans and the Socialists, who always saw themselves as direct heirs of the Risorgimento currents. Each group felt associated with a particular personality of the Risorgimento: the Liberals with Cavour, the Republicans with Mazzini and the Socialists with Garibaldi .

The Italian Socialists appeared from the beginning as a mass party and opened up to the general public. After 1900 the Catholics followed, first with the Democrazia Cristiana Italiana by Romolo Murri , then with the Partito Popolare Italiano by Luigi Sturzo . Both the Socialists and the Christian Democrats achieved considerable electoral successes up to the establishment of the fascist dictatorship and were decisive for the loss of the strength and authority of the two old collective movements of the liberal ruling class, which could no longer give their concerns any weight by founding a new party.

In December 1914, Benito Mussolini and Alceste de Ambris founded the movement Fascio d'azione rivoluzionaria , which campaigned for Italy to enter the war. After achieving this goal, it dissolved again in 1915. In 1919 the fighting alliances Fasci Italiani di combattimento followed , from which in 1921 the National Fascist Party emerged . In the same year, the split between the socialists gave rise to the Communist Party of Italy (Italian Partito Comunista Italiano ). At the time of its inception, the PCI was no different from other European communist parties. In terms of share of the vote and number of members, it was much smaller than the socialists or social democrats. These newly emerging extreme currents supplemented the previous party landscape and sealed the insignificance of the old liberal parties. The three new movements, Catholic, Fascist and Communist, emerged in the short period between the end of the First World War and the beginning of the era of Italian fascism and can be seen as the second generation of Italian parties. The then common name for these three large mass parties was derived from their party colors and was white for the Christian Democrats, black for the fascists and the red for the socialists and communists.

With the dissolution of the Partito Nazionale Fascista following the fall of Mussolini in 1943, only the Christian Democrats and Communists achieved the importance of the pre-war period in the parliamentary elections of June 2, 1946 after the end of the Second World War . The communists particularly benefited from their key role in the resistance against the German occupation regime in northern Italy from 1943 to 1945. Even after the end of the monarchy, the Democrazia Cristiana remained the dominant force in Italy until 1994.

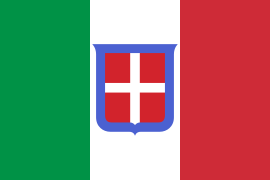

State symbols

The kingdom's first national coat of arms was adopted from Sardinia-Piedmont. In the middle it contained the coat of arms of the House of Savoy and four Italian flags, which date from 1848. On May 4, 1870, two lions in gold , which now bore the heraldic shield , a crowned knight's helmet , which around its collar the Military Order of Savoy , the Order of the Crown of Italy , the Knightly Order of St. Mauritius and Lazarus and the Order of Annunciations . The motto FERT was deleted. The lions wielded lances that held the national flag. From the helmet fell a royal cloak, which was supposed to protect the nation. Above the coat of arms was the star of Italy (Italian Stella d'Italia ).

The newly adopted state coat of arms of January 1, 1890 removed the fur coat and the lances and the crown on the helmet was replaced by the iron crown of the Lombards . The whole group stood under a canopy crowned with the Italian royal crown, over which was the banner of Italy. A golden, crowned eagle carried the flagstick .

On April 11, 1929, Mussolini replaced the two Savoy Lions with bundles of lictors . Only after his dismissal in 1944 was the old coat of arms from 1890 restored.

- Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Italy

The national colors of the monarchy were green , white and red in vertical stripes. In the middle was the Savoy coat of arms . This flag was first used in 1848 as the war flag of the army of the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont. On April 15, 1861, this flag was declared the flag of the new state. This formed the first Italian national flag and was the flag of Italy for a total of 85 years until the founding of the republic in 1946 .

In 1926 the fascist government tried to redesign the national flag by adding a bundle of lictors. However, this attempt met with strong opposition , mainly from the old elites and the army. As a compromise, the fascists' black flag was officially hoisted next to the national flag at home, but this was not of any greater importance.

- Flags of the Kingdom of Italy

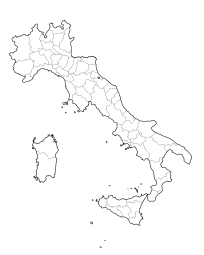

Administrative organization

The Kingdom of Italy adopted the so-called Rattazzi Law (also called Savoy State Law ), which was enacted by the then Sardinian Interior Minister Urbano Rattazzi on October 23, 1859 and was based on the administrative structure of France . It prescribed the organization of the territory into provinces , districts, counties and parishes . The representatives of the local authorities should be elected by the people for a certain period of time. The first elections were held on January 15, 1860, before the state was founded. In 1929 local elections were abolished and only reintroduced in April 1944.

The Kingdom of Italy was administratively divided into provinces, counties ( circondari ), districts ( mandamenti , these only for the administration of justice) and municipalities. Each province was headed by a prefect. It represented the executive power and had the prefectural council at its side for its support , which consisted of a number of councilors, secretaries and subordinate officials. In each district a sub-prefecture was set up, the board of which, the sub-prefect, took care of the administrative business of the district under the direction of the prefect. By 1914 there were 69 prefectures, 137 sub-prefectures and 78 district commissariats throughout Italy. Under the prefects and sub-prefects (district commissioners), the community leaders (Sindaci, see above) acted as government officials. The security police were led by the prefects, sub-prefects (or district commissioners) with attached inspectors and delegates, in twelve large cities by quaestors (with inspectors). In each province there was a medical council, a school council, a post office, a finance department and a building office; 9 telegraph offices, 34 forest departments and 8 mining offices were used for larger areas. As far as the supervision of the provinces and municipalities by the state was concerned, the prefects had to examine the protocols and resolutions of the municipal and provincial councils, and the provincial council was responsible for overseeing the municipalities' budgets and the like Appeal possible. The king could dissolve the municipal and provincial councils, in urgent cases even the highest provincial official. However, a new election had to be ordered within three months of the dissolution. When the provincial council was dissolved, the prefect and the prefectural council came in, and when the municipal council was dissolved, a royal commissioner took office.

In contrast to today's Italian republic, which partly includes federal structures, the Kingdom of Italy was a very centralized state. There were no autonomous or independent regions . Today's Italian regions only existed as a summary of the provinces for statistical purposes and economic planning. This repeatedly led to uprisings and revolts, such as the brigade war in southern Italy (1861–1868) or the movement of the Fasci Siciliani (1891–1894).

The island of Sicily received its first statute of autonomy by the royal decree 15th of May 15, 1946 from Umberto II.

- Provinces of the Kingdom of Italy

military

The King of Italy was Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Italian Army from 1861 to 1940 and 1943 to 1946. The monarch had extensive powers in the military. A parliamentary control took place only through the approval of the financial means. The king had the right to determine the strength of the presence, to determine the garrisons, to build fortresses and to ensure uniform organization and formation, armament and command as well as the training of the men and the qualifications of the officers.

The highest military rank in the Royal Italian Army was First Marshal of the Empire (Italian Primo maresciallo dell'Impero) , which only King Victor Emmanuel III. (1938), Benito Mussolini (1938) and Pietro Badoglio (1943, de facto).

The Royal Italian Army was divided into three branches:

- Regio Esercito (Royal Army or Army)

- Marina Regia (Royal Navy)

- Aeronautica Regia (Royal Air Force)

- Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale ( Voluntary National Security Militia known as Black Shirts, loyal to Benito Mussolini, abolished in 1943)

Demographics and Society

After unification and throughout the liberal period, Italian society was heavily divided into classical, linguistic, regional and social lines. Common cultural traits in Italy at the time were socially conservative in nature, including a strong belief in the family as an institution and patriarchal values. Aristocrats and medium-sized families were very common in Italy at the time. The honor was strongly emphasized. After the unification, the number of nobles had increased to around 7,400 noble families , with the nobility divided into the loyal "whites" (Italian Nobiltà bianca ) and the increasingly insignificant pope-loyal "black nobility" (Italian nobiltà nera ). Many wealthy landowners (especially in the south) held feudal control over "their" farmers.

Population development of the Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946) :

| year | 1861 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1946 |

| Population in millions | 22,182 | 25.766 | 28,437 | 30.947 | 32,475 | 34.565 | 37.837 | 40.703 | 43.787 | 45.380 |

| | |

The economy of southern Italy suffered greatly after Italian unification. The process of industrialization took place there only hesitantly and only at the turn of the 20th century there was a slight economic upturn. The poor economic situation in the south fueled poverty and organized crime . The Italian governments believed they could counter this with repression . The poor social conditions led to the rise of the brigands , who in the 1860s waged a guerrilla war of almost a decade in the south against the central government in Rome . This and the ruthless approach of the army destroyed a large part of the existing infrastructure in the south. This sparked massive Italian emigration that resulted in a worldwide Italian diaspora (especially in the United States and South America ). Many southern Italians also settled in the northern industrial cities, such as Genoa , Milan and Turin . Politically, too, the south was often at odds with the north, for example in the referendum on the form of government in 1946, when the majority of the population in the south voted for the preservation of the monarchy.

After the end of the liberal era, from 1922 onwards, the fascists pursued the concept of a totalitarian unitary state, which should include all social classes. Italy became a one-party dictatorship . Mussolini and the fascist regime oriented Italian culture and society on ancient Rome and on some futuristic aspects of some intellectuals and artists. Under fascism, the definition of Italian citizenship was based on a militaristic attitude and an idealized “ new people ” ideal. Personal individualism had to subordinate itself to the state and the community. In 1932 the fascists presented their ideology in the La dottrina del fascismo : Features were extreme nationalism , a world power position for Italy aimed at through war , the emphasis on the “will to power” ( Friedrich Nietzsche ), the authoritarian leader principle ( Vilfredo Pareto ), the "Direct action" as a "creative design principle" ( Georges Sorel ) and a merger of the state and the sole ruling party. The prescribed uniform organization of workers and entrepreneurs in cooperation should prevent class struggle . In order to gain not only power but also hegemony in the sense of Antonio Gramsci , the state also took over the sports movement. This was intended to promote body cult, the glorification of strength , masculinity and the demonstration of Italian superiority in body-related activities such as sports , the World Cup and the Olympic Games . The Comitato Olimpico Nazionale Italiano was nationalized. and top-class sport made internationally efficient with state amateurs . The women were encouraged to motherhood and prohibited from participating in public affairs.

Initially, Italian fascism was not anti - Semitic . Mussolini repeatedly distanced himself publicly from the racism and anti-Semitism of the National Socialists . It was not until 1936 that there was anti-Semitic agitation as a result of Mussolini's alliance with the German Reich , which then culminated in the enactment of the anti-Semitic race laws in 1938 .

The fascist “New Order” in Italy differed significantly from the Nazi regime in terms of its statism , in that Mussolini's strong state incorporated the old elites. However, several attempts to integrate the old elites and officers into the party failed. The influx came mainly from the civil service. The military leadership again remained strongly monarchist and traditionalist. The Italian fascist party therefore never achieved dominance over all areas of society such as the NSDAP in Germany or the CPSU in the Soviet Union . In the endeavors to create a new culture, too, the efforts of fascist Italy did not prove to be as successful in comparison to other one-party states such as Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union.

Mussolini's propaganda stylized him as the “savior of the nation”. The fascist regime tried to make his person omnipresent in Italian society. Much of the appeal of fascism in Italy was based on the personality cult around Mussolini and his popularity. Mussolini's passionate eloquence at large rallies and parades served as a model for Adolf Hitler. The fascists spread their propaganda through the newsreels , the radio and a couple of feature films . In 1926 a law was passed which made it mandatory to show propaganda shows in cinemas before every feature film. Fascist propaganda glorified war and promoted its romanticization in art. However, the artists, writers and publishers were not subject to strict controls. They were only censored if they had blatantly opposed the state.

In 1860 Italy had no established national language. The Tuscan dialect , on which the modern standard Italian language is based, was only spoken around Florence , while regional languages or dialects dominated in the other parts of the country . Only two percent of the population spoke Italian as a written language. King Viktor Emmanuel II also spoke almost only Piedmontese and French . The illiteracy was high: in 1871 were 61.9 percent of Italian men and 75.7 percent of women are illiterate. This illiteracy rate was far higher than that of Western European countries over the same period. Due to the variety of regional dialects, no national popular press was initially possible.

Italy had few public schools after unification . The Italian governments during the liberal era tried to improve literacy by creating state-funded schools where only the official Italian language was taught.

The fascist government supported a strict education policy in Italy with the aim of finally eliminating illiteracy and strengthening the loyalty of the population to the state. The first education minister of the fascist government from 1922 to 1924, Giovanni Gentile , directed educational policy towards indoctrination of students towards fascism. The fascists educated youth to obedience and respect towards the authority . In 1929 the fascist government took control of the admission of all textbooks and forced all high school teachers to swear allegiance to fascism. In 1933 all university professors were obliged to join the National Fascist Party. In the 1930s to 1940s, the Italian education system increasingly focused on the subject of history, which tried to portray Italy as an important force in civilization . In fascist Italy, intellectual talents were rewarded and promoted in the Accademia d'Italia, founded in 1926 .

The standard of living of the Italians improved continuously after unification, but remained - especially in the south - below the Western European average. Various diseases such as malaria and some epidemics have broken out in southern Italy . The death rate was 30 people per 1,000 people in 1871, but could be reduced to 24.2 per 1,000 by the 1890s. The child mortality rate was also very high. In 1871, 22.7 percent of all children born that year died, while the number of children who died before their fifth birthday was 50 percent. The proportion of children who died in the first year after birth fell between 1891 and 1900 to an average of 17.6 percent. An effective social policy was lacking in Italy during the liberal era. State social security was only introduced in 1912 . In 1919 an unemployment insurance was created . Italian social policy achieved great successes in fascist Italy. In April 1925 the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro (OND) was founded. The OND was the largest state recreational organization for adults. The organization was so popular that it owned a clubhouse in every Italian city by the 1930s. The OND was responsible for the construction of 11,000 sports fields, 6,400 libraries, 800 cinemas, 1,200 theaters and more than 2,000 orchestras. Membership was voluntary and apolitical. The enormous success of the organization led to the founding of the organization Kraft durch Freude in Germany in November 1933 , which adopted its model.

Another organization was the youth organization Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB), founded in 1926 , which gave young people cheap access to clubs, dance events, sports facilities, radios, concerts, theaters, circuses and hikes or organized them for young people.

On September 20, 1870, the Royal Italian Army occupied the Papal States and the city of Rome. The following year the capital was moved from Florence to Rome. For the next 59 years after 1870 the Catholic Church refused to recognize the legitimacy of Italian royal rule in Rome and with the Bull Non expedit the Pope forbade Italian Catholics to participate in elections of the new state in 1874. This was followed less and less by the Catholic lay people, which is why it was relaxed in 1909 and finally abolished in 1919, when the state and the church came closer again after the First World War. The Partito Popolare Italiano emerged as a Catholic party, which immediately became one of the most important political forces in the country and can be considered a forerunner of Christian Democracy .

Liberal governments have generally followed a policy of limiting the role of the Catholic Church and its clergy. Church land was seized en masse, processions and Catholic festivities were partially prohibited and otherwise required state approval, which was often refused. The leading politicians of the kingdom were secular and anti-clerical , many were positivists or members of the Freemasons' League . Other religious communities such as Protestants or Jews were legally equated with Catholics; as in other European countries, new religious and non-religious movements such as socialism and anarchism emerged . However, Catholicism remained the religion of the vast majority of Italians. Relations with the Catholic Church improved significantly during Mussolini's regime. Mussolini, once an opponent of the Catholic Church, entered into an alliance with the Catholic Partito Popolare Italiano after 1922 . In 1929 Mussolini and Pope Pius XI. an agreement that ended the stalemate. This process of reconciliation had already begun under the government of Vittorio Emanuele Orlando during the First World War.

Mussolini and the leading fascists were not devout Christians, but they recognized the opportunity to build better relationships with the influential church and to stage it propagandistically as allies in the fight against liberalism and communism. The Lateran Treaty of 1929 recognized the Pope as ruler of the small state of Vatican City within Rome and made the Vatican a more important hub of world diplomacy. A nationwide referendum in March 1929 confirmed the Lateran Treaty. Almost 9 million Italians, or 90 percent of registered voters, voted yes and only 136,000 voted no. The treaties are still in force today.

The 1929 Concordat declared Catholicism the state religion , obliged the Italian state to pay the salaries of priests and bishops, to recognize church marriages and to reintroduce religious instruction in public schools. Again the bishops swore allegiance to the Italian state, which was granted a veto right when they were selected . A third agreement resulted in the payment of 1.75 billion lira (approx. 100 million US dollars ) for the incursions of church property since 1860. The church was not officially obliged to support the fascist regime, but above all it supported the aggressive foreign policy, like the support for the coup plotters of Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War and the conquest of Ethiopia . Conflicts persisted, especially around the youth network of the Catholic Action , which Mussolini wanted to merge with the fascist youth group. In 1931 Pope Pius XI. the encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno (“We have no need”), in which the Church criticized the decades-long persecution of the Church by the Italian state and the “pagan worship of the state” among the fascists.

economy

In the entire period from 1861 to 1940 Italy experienced a considerable economic boom , despite several economic crises and the First World War. In contrast to most modern nations, where this industrial boom was due to large corporations , industrial growth in Italy was due to mostly small to medium-sized family businesses.

Political unification did not automatically lead to economic integration , because Italy faced serious economic problems in 1861 and the different economic systems and different economic developments of the predecessor states led to sharp contradictions at the political, social and regional level. During the liberal period, Italy managed to industrialize strongly in several steps, although the country was the most backward country among the great powers after the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan and remained very dependent on foreign trade and international prices for coal and grain .

After unification, Italy had a predominantly agricultural society, with 60 percent of the labor force working in agriculture. Advances in technology increased export opportunities for Italian agricultural products after a period of crisis in the 1880s. As a result of industrialization, the share of those employed in the agricultural sector fell to below 50% at the turn of the century. However, not all benefited from these developments, as southern agriculture in particular suffered from hot summers and the arid climate , while the presence of malaria in the north prevented the cultivation of low-lying areas on the Italian Adriatic coast .

The overwhelming attention to foreign and military policy in the early years of the state led to the neglect of Italian agriculture, which had been in decline since 1873. Both radical and conservative forces in the Italian parliament demanded that the government examine ways of improving the agricultural situation in Italy. The investigation, initiated in 1877, lasted eight years and showed that agriculture was not improving due to the lack of mechanization and modernization and that the landowners did nothing to develop their lands. In addition, most of the workers on the agricultural land were not farmers, but inexperienced short-term workers ( braccianti ) who were employed for a year at best. Peasants without a steady income were forced to live on poor food. Disease spread rapidly and a major cholera epidemic broke out, killing at least 55,000 people. Most of the Italian governments could not deal effectively with the precarious situation due to the strong position of the big landowners in politics and economy. This fact was confirmed in 1910 by a new commission of inquiry in the south.

Around 1890 there was also a crisis in the Italian wine-growing industry - almost the only successful sector in agriculture. Italy suffered from overproduction of grapes . In the 1870s and 1880s, viticulture in France suffered from a crop failure caused by insects. As a result, Italy became the largest exporter of wine in Europe. After the recovery of France in 1888, Italian wine exports collapsed and there was even greater unemployment and numerous bankruptcies of Italian winegrowers.

From the 1870s onwards, Italy invested heavily in the development of railroads, and from 1870 to 1890 the existing route network more than doubled.

During the fascist dictatorship, enormous sums of money were invested in new technological achievements, particularly in military technology. Large sums of money were also spent on prestige projects such as the construction of the new Italian ocean liner SS Rex , which set a transatlantic sea voyage record of four days in 1933, and the development of the Macchi-Castoldi MC72 seaplane , which was the fastest seaplane in the world in 1933. In 1933 Italo Balbo took a seaplane flight across the Atlantic to the Chicago World's Fair . The flight symbolized the power of the fascist leadership and the industrial and technological progress of the state which it had made under the fascists.

Gross domestic product of the Kingdom of Italy according to Angus Maddison (1861–1946) :

| year | 1861 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1945 |

| Gross domestic product in billion US dollars (1990) | 37,995 | 41,814 | 46,690 | 52,863 | 60.114 | 85.285 | 96,757 | 119.014 | 155.424 | 114,422 |

Il Mezzogiorno in southern Italy

Southern Italy remained more or less an economic and political problem area throughout the time of the Kingdom of Italy. There were repeated uprisings and revolts, the economy remained rather backward compared to the north and the population suffered from a high rate of illiteracy and organized crime. Most of the inhabitants of southern Italy were farmers or farm workers. The 1881 census found that over 1 million day laborers in the south were chronically underemployed and were likely to become seasonal emigrants in order to secure themselves economically. The southern farmers as well as the small landowners were often in conflict with them.

The unification of Italy created a growing economic divide between the northern provinces and the southern half of Italy. In the first decades of the new kingdom, the lack of effective land reform , heavy taxes, and other economic measures imposed on the south, along with the elimination of protectionist tariffs on agricultural goods imposed to promote northern industry, led to a tremendous one Decline in production of southern Italian agricultural goods. Many farmers, small businessmen and landowners emigrated, especially from 1892 to 1921 there was a strong wave of emigration. From the 1870s onwards, this fact preoccupied numerous intellectuals, scholars and politicians who wanted to investigate the economic and social conditions in southern Italy ( Il Mezzogiorno ). This group ( meridionalismo ) gained increasing influence from 1900 under Giovanni Giolitti .

The rise of the brigands and the mafia led to widespread violence, corruption and illegality. Prime Minister Giolitti once admitted that there were places where the law would not work at all. After the rise of Benito Mussolini, the "iron prefect" Cesare Mori tried to fight the already powerful criminal organizations in the south with some success. However, when connections between the mafia and the fascists became known, Mori was deposed and the fascist propaganda declared the so-called "battle against the mafia" over and won.

There was also a major economic boom in the south under the fascists. Economically, the fascist policy was aimed at the creation of an Italian world empire and weighted the strategically important southern Italian ports, which were to become the starting point for the colonial expansion of Italy, higher than the previous governments of the liberal era. There was an economic and demographic boom in Naples in particular , but this was mainly due to the personal interest of King Victor Emmanuel III, who was born there.

Early years

The new Italian nation-state faced major domestic and foreign policy problems in its early years. Therefore the establishment of the state began slowly and hesitantly. These early years from 1861 to 1876 were determined by mostly short-term governments of the conservative- monarchist party historical right (“ Destra Storica ”). This won most of the elections from 1861 to 1874 and formed nine of the eleven governments up to 1876. Its members were mostly large landowners and industrialists as well as military officials ( Bettino Ricasoli , Quintino Sella , Marco Minghetti , Silvio Spaventa , Giovanni Lanza , Alfonso La Marmora , Emilio Visconti -Venosta ) from northern Italy.

In the interior of the kingdom, the state-driven secularization intensified the conflict with the Catholic Church from 1867/68, the war with the brigands in the south reached its climax in 1864/65, and centralism, which ruthlessly suppressed centuries-old regionalisms and linguistic differences, led to it separatist tendencies in the south and a severe crisis in agriculture . In terms of foreign policy, the new nation was initially isolated . The young nation-state only maintained good relations with the Second French Empire . In the case of Great Britain , Italy had discredited itself by ceding Nice and Savoy to France.

Nevertheless, Cavour's successors managed to calm the situation down. The brigant war ("brigantaggio") overshadowed the structure again and again. It was carried by several thousands of insurgents organized in gangs and supported by the majority of the population in the mountainous regions of southern Italy. They were initially also supported by the Papal States and destroyed and looted the new state institutions. They also succeeded in attacking entire army battalions and police forces. The reasons were the lack of improvement in conditions in the south (in the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ), where there was no reform of the state administration and an increase in taxes.

The Royal Italian Army, numbering around 100,000 men, did not succeed in eliminating the guerrilla fighters for the time being . At the height of the war they ruled several important cities and entire regions of the south. The state therefore proceeded with the utmost severity. Exceptions and martial law were imposed, shootings under court martial law , the destruction of villages and fatal collective arrests with a total of 130,000 dead. On August 15, 1863, the government of Marco Minghetti imposed the so-called Pica Law , which provided for the suspension of constitutional rights in the provinces affected by robbery. The war lasted from 1861 to 1865 and 1866 to 1870.

In 1865, under Prime Minister Alfonso La Marmora, civil and commercial law and the code of criminal procedure were standardized . To a criminal unification did not occur until 1889. In foreign policy, guaranteed Italy and France with the September agreement of 15 September 1864, the integrity of the remaining Papal States. The treaty provided for the withdrawal of French troops from Rome within two years. In return, Italy undertook to support the Papal States in times of crisis, to enable the establishment of a corps of volunteers and to take on a share of the papal national debt. An initially secret additional protocol regulated the change of the capital of Italy within six months. First, the capital should be moved from Turin to Naples . Florence was later chosen , despite protests from King Victor Emmanuel II and bloodied demonstrations in Turin. The relationship between king and pope remained tense. Also because the Italian state banned all religious orders in May 1874 and confiscated their property.

A treaty with the German Customs Union followed in 1865 and a secret alliance with Prussia on April 6, 1866, which led Italy out of isolation. The monarchy remained de facto dependent on France until 1871.

The new state also faced a difficult financial situation. The financing of the Risorgimento had exhausted the finances of the Sardinian state (creation of a modern army by Cavour and Alberto La Marmora ), in addition to the costs of the military ventures in Italy and the Sardinian participation in the Crimean War. Despite the tax burden from Lire 82 million in 1850 to Lire 145 million in 1858, the Sardinian government did not have sufficient funds. The public debt grew from 420 million lire in 1850 to 725 million in 1858. In 1866 the budget deficit had risen rapidly to 721 million lira. In order to prevent bankruptcy, the convertibility of notes to gold was suspended after the German War in 1866 and a state-fixed rate of the lira was introduced through the “Corso forzoso”. From 1868 onwards there were massive tax increases and the sale of some state monopolies, which led to violent social protests. However, the decision to introduce general conscription in 1872 made the situation much worse.

In order to rehabilitate the ailing state finances, King Viktor Emanuel II reappointed Minghetti as Prime Minister on July 10, 1873. In his second term in office, he pursued a strict accounting policy, which in 1876 led to the budget balancing . He also wanted the state to act as a “key set” in laying the foundations for economic modernization. He mainly relied on the construction of the railways , which by 1879 had grown to around 8,000 kilometers of track. However, due to insufficient investment in education and because private or foreign investments in the still young industry largely failed to materialize, state expenditure could not be compensated and there were tax increases in the consumer sector and lower real wages in state-owned companies. After all, Italy was at times the country with the highest consumption taxes and the lowest wages in Central and Western Europe. At the same time, the increasing importation of foreign agricultural products triggered a crisis in agriculture. There was a rural exodus to the big cities and emigration to overseas increased. Therefore, after its proclamation as the capital, Rome was extensively redesigned.

Liberal Era (1876-1922)

After the death of King Victor Emmanuel II in 1878, Italy developed under his successors Umberto I and Victor Emmanuel III. to a de facto parliamentary monarchy based on the British model. The next four decades of the new nation-state were marked by a long liberal period, which in domestic and foreign policy was marked to a large extent by the actions of individuals, not parties, who were unable to develop any politicizing and nation-building power due to the extreme census suffrage . The time is divided into three phases: From 1876 to 1887 the left-wing liberal Agostino Depretis began the reform of the state, which paved the way for Italy to become the sixth European great power . In the following time, his successor Francesco Crispi tried to strengthen the state and until his overthrow in 1896 pursued an aggressive and militaristic foreign policy, which was aimed at the conquest of East Africa and Italian supremacy in the Mediterranean . From 1900 Giovanni Giolitti largely dominated political events and initiated a gradual democratization of the class system.

The early years of the liberal era were marked by the economic crisis of the 1880s, which ruined southern Italy economically, unemployment and an increasing wave of emigration. These problems put a great strain on the relationship between state and society and led to the formation of two major opposition groups: the socialist-anarchist and the Catholic. The socialists and republicans succeeded in gradually getting into parliament as early as the 1880s, while the Catholics organized themselves into non-political organizations.

The beginning of Italian imperialism from 1887, with which the various Italian governments wanted to redirect emigration to their own colonies (social imperialism ), went hand in hand with the high industrialization in northern Italy, which was driven forward at the same time , which made the country one of the world's leading countries by the turn of the century Industrial nations rose. Nationalism and irredentism, which grew stronger around the turn of the century, increasingly strained relations with the allies in the Triple Alliance and led to the conquest of Ottoman Libya in 1911 .

The First World War and the subsequent national crisis finally ended the liberal era with the fascist march on Rome in 1922.

The left in power

On March 18, 1876, in a vote in parliament, the opposition overthrew the Minghetti government. The reason for this was the attempt to nationalize the Italian railways that were sold to private companies in 1865.

The king feared a minority government and commissioned the left-liberal opposition leader Agostino Depretis on March 25, 1876 to form a government. Depretis was the undisputed leader of the party of the historical left (" Sinistra Storica ") and had a lot of political experience. It was also the first time in the new Kingdom of Italy that a government was led only by left-wing men.

The party that came to government was, however, at odds. The ideological matrix of the group was progressive- liberal, but was also influenced by the ideas of Giuseppe Mazzini and Garibaldi. Depretis therefore formed a government that, in addition to the support of the left, could also count on the support of part of the right that had contributed to the overthrow of the Minghetti government. In his reign, Depretis always sought broad approval for individual problems with parts of the opposition, which led to the phenomenon of " trasformismo " (transformation). Despotic and corrupt acts, which were reflected in authoritarian measures such as the prohibition of public gatherings and the banishment of individuals classified as "dangerous" to remote penal islands throughout Italy, however, also shaped the reign of Depretis.

The elections of November 1876 confirmed Depretis' stabilization and détente policy and were a success: 414 members of the left were elected, while only 94 of the right were elected.

Rise to a great power and a new foreign policy

In foreign policy, Depretis cautiously pushed through a rapprochement with the new German Reich in his first government in order to counteract the current French policy of restoring the power of the Church and of ultra-montanism under President Patrice de Mac-Mahon . This Francophobic attitude deepened in May 1877 when the government of Albert de Broglie was formed in Paris , which favored clerical positions. The political crisis in France and the uncertainty in the Balkans due to the Russo-Turkish War prompted him to send the President of the Chamber of Deputies ( Camera dei deputati ) Francesco Crispi on a fact- finding mission to London, Berlin, Paris and Vienna to find new allies for Italy to win. The mission was unsuccessful and a new German-Italian alliance against Austria-Hungary also failed due to the resistance of the German Chancellor Bismarck .

The slow domestic stabilization of Italy, the small economic boom and the expansion of the Royal Italian Army into a powerful armed force soon enabled Italy to rise to become one of the major European powers . This appreciation was confirmed at the Berlin Congress from June 13, 1878 to July 13, 1878. Still, Italy remained isolated and could not acquire Ottoman Albania , Tunisia or Libya . Instead, the kingdom had to accept the administration of Austria-Hungary over occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina , the new British rule over Cyprus and guarantees for France over Tunisia. A failed assassination attempt by the anarchist Giovanni Passannante on Umberto I in Naples provided the opportunity to overthrow the first Cairoli government on December 19, 1878 on charges of weakness.

Depretis returned to his post on December 19, 1878, and because of Italy's still sensitive international position, he also took over the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Despite the slow consolidation of alliances in Europe ( three-emperor agreement , three emperor's union , two-emperor ), he did not pursue a clear strategy in relations with other countries. However, because of the mostly short terms of office, it was difficult to take a lasting direction in foreign policy.

Italy's foreign policy situation deteriorated when France seized Tunisia in 1881, in which Italy was also interested. The so-called blow of Tunis (“schiaffo di Tunisi”) was the last act in a series of foreign policy failures of the second Cairoli government (in office since July 14, 1879), whose open irredentism cooled relations with the Habsburg Empire and relations with France were tense because of the competition between the two powers for Tunisia. Despite promises by French Prime Minister Jules Ferry not to annex Tunisia, French troops marched into Tunisia on May 1, 1881, and made Tunisia a French protectorate on May 12 in the Bardo Treaty . The Cairoli government, overwhelmed by public criticism and outrage in Italy, resigned on May 29. The king commissioned Quintino Sella to form the new government, but resorted to Depretis after unsuccessful attempts. In his fourth term in office, he prioritized foreign policy and now adopted a strict and consistent direction. Indeed, after the dispute at the Berlin Congress and the blow in Tunis, he decided to resolve the question of alliances. In this regard, King Umberto I was inclined to come to an understanding with Austria-Hungary and Germany that would strengthen the monarchy in a conservative manner. In October 1881 he and the monarch went to Vienna, where the first attempts to get closer were made.

The rapprochement with the later Central Powers was unpopular in large parts of the population because of the earlier wars with Austria. Contrary to the king's expectations, Depretis also tended to form an alliance with Paris. He believed that the consequences of the occupation of Tunisia would not threaten Italy and argued with the 400,000 Italian immigrants living in France around 1880. However, the foreign minister chosen by Depretis, Pasquale Stanislao Mancini , was in favor of an alliance with Germany, which was growing economically and militarily. However, Bismarck did not trust Depreti's government because it was close to the ideas of the new revisionist French Prime Minister Léon Gambetta . Instead, he first convinced inside the monarchy at the beginning of 1882 that an alliance would be useful if it did not mean war with France. On May 20, 1882, the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was signed in Vienna , which broke the isolation of Italy and enabled the country to be integrated into the European balance of power . The alliance determined Italian foreign policy for the next 20 years and initially protected Austria-Hungary from Italian territorial claims.

A few months later, however, there was a first crisis within the alliance. The trigger was the execution of the Italian Guglielmo Oberdan on December 20, 1882 in Trieste , who was accused of an assassination attempt on Emperor and King Franz Joseph I. In Italy, the execution sparked protests and the Triple Alliance continued to decline in popularity.

Depreti's government had to cope with a wave of anti-Austrian feelings among the people, which resulted in violent demonstrations and attacks on Austrian offices and consulates in Rome, and behaved neutrally. But despite the government's best efforts to achieve reconciliation, the death of Oberdan opened up a large rift between Italy and Austria. Relations with the Austrian ally remained difficult. Also because Austria-Hungary was preferred by Germany and the two powers did not recognize Italy as an equal partner.

Domestic reforms

The long reign of Depretis made numerous reforms possible. On July 15, 1877, the Minister of the Interior, Michele Coppino, presented a law that stipulated two years of free compulsory and secular basic education and six to nine years of voluntary schooling for children. Compulsory religion classes ended for what demonstrated the violent anti-clericalism of the left. However, the reform led to criticism because of its high cost. In December 1877, Depretis threatened to be overthrown by his more radical internal party rival Cairoli. King Victor Emmanuel II supported Deperti's program and kept him in office. It was the last important political act of the monarch, who died on January 9 of the next year. The new second government, in which Crispi, who was ready for more reforms, became Minister of the Interior, pushed through the abolition of the Ministry of Agriculture. Promoted industry and trade, and established the Treasury Department to gain better control over government spending. Such decisions and decrees were, however, taken without the parliamentary participation that was actually required. The moderation of the hated flour tax on June 24, 1879 was approved by the Senate . After the elections of May 16, 1880, in which his party melted from 414 to 218 seats, Depretis was dependent on the support of parliament in all matters and continued his reform policy as interior minister and prime minister in personal union. In January 1882 he expanded the right to vote . All men who were at least 21 years old, who had attended two years of elementary school or who could raise an annual tax of more than 19.80 lire had the right to vote. Under this law, the proportion of eligible voters grew from 2.2% of the population in 1879, 621,896, to 2,049,461, or 6.9%. That is more than a quarter of the adult male population at the time.

With the approach of the first major elections, which were held from October 29 to November 5, 1882, the rise of the extreme left (" Estrema sinistra ") accelerated the disintegration of the traditional political parties. The two old political parties reacted to such upheavals by decreasing ideological conflicts and overcoming their differences. As a result, the concept of trasformismo prevailed, in which Depretis knew how to bind parts of the moderate opposition to himself and to be able to control the progressive advances of the radicals and republicans in parliament through a new, moderately reformist, centrist political camp.

This concept had provoked great tension within the left. When Depretis threatened to overthrow in May 1883, the leader of the right-wing Minghetti decided to give Depretis special support in order to slow down the extreme wings of parliament and thus to slow down the rise of popular sovereignty in fear of anarchy and despotism . Nevertheless, from 1885 Depreti's term of office was drawing to a close. The elections of May 1886 brought Depretis only a small gain in votes and several right-wing MPs refused to support him after Marco Minghetti's death in December 1886. This was followed by the agricultural crisis, which led to the abolition of the grinding tax in 1884.

Economic modernization

Economically, Depretis pursued a protectionist policy, pushed the industrialization of Italy and the modernization of the Royal Italian Army and Navy. In 1878 he made the import of raw materials easier than finished products in the customs tariff and in 1883 abolished the mandatory rate for the lira. The protectionist measures should serve as preparation for the adaptation to the climate of the international competition and brought an increase of the industrialization in the north, especially in the textile and steel industry . The years of Depreti's government were also marked by a significant increase in the road and rail network, which at the end of the 1880s comprised a route network of 12,000 km. In 1882 the Gotthard tunnel was opened with Switzerland .