Flight over Vienna

The flight over Vienna was a propaganda flight by several Italian reconnaissance planes during the First World War . At the company headed by Gabriele D'Annunzio on August 9, 1918, several thousand leaflets were dropped over Vienna .

prehistory

As early as October 1915, Gabriele D'Annunzio toyed with the idea of flying over the capital of the enemy. At this point he had already distinguished himself as an aircraft observer and had dropped propaganda publications about Trieste (August 7, 1915) and Trento (September 20, 1915). Before that, he had to pull out all the stops and even go to Prime Minister Salandra so that he could even be put into active service at the age of 52.

The flight over Vienna was not an exclusive idea of D'Annunzio. Rather, he picked it up in a conversation with Ugo Ojetti in October 1915 and was able to cleverly collect it for himself in the following years, even if it remained pure utopia because of the inadequate aircraft at the time .

The thought still didn't let go of him. After an enemy flight over Gorizia , he signed a souvenir photo with Donec at metam: Vienna (German to the destination: Vienna). D'Annunzio's ambitions were dampened after his eye injury in January 1916 when his head hit the fuselage during an emergency landing . In retrospect, the poet portrayed it as having hit the plane's machine gun. After the accident, his right eye was blind for a few hours. For fear of no longer being able to fly, he did not seek treatment despite the complaints, which ultimately cost him the loss of his right eyesight and a forced rest break.

In December 1916, some officers of the 4th Bomber Squadron took up the idea again. When the new, much improved Caproni bomber of the type Ca. 3 was available, they wanted to confront the hesitant high command with a fait accompli. Due to adverse circumstances and full operational plans, the secretly planned project had to be postponed again and again. Nevertheless, it was not abandoned, as it was feared that D'Annunzio would be given preference if the High Command accepted. At the end of August 1917, the departure could finally be scheduled for August 30th.

D'Annunzio, meanwhile recovered from his eye injury, learned about the unauthorized company and was just able to prevent it through clever intervention with the superiors. He now set about getting a corresponding clearance himself. After a letter to Cadorna , he received the green light for a nine-hour test flight, which was successfully completed on September 4th. A final release was denied to him, because after the intervention of Benedict XV. and his peace note Dès le début did not want to endanger the negotiations on a ceasefire with the provocative action.

After the disastrous Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo at the end of October 1917, the company had to be put on hold. In the spring of 1918, D'Annunzio's interest was aroused again after several successful long-haul operations, with flights via Innsbruck , Friedrichshafen , Cattaro and Zagreb . In mid-June 1918, the Italian high command decided to fly to Vienna with the 87ª Squadriglia «Serenissima», which was equipped with the fast single-seat SVA 5 long-range reconnaissance aircraft , which would have led to the automatic exclusion of D'Annunzios, who had meanwhile been promoted to major. After energetic protests by D'Annunzio, he was allowed to participate in the company with a two-seater prototype from SVA, which, however, broke during a test flight in early July. As a result, a two-seater SVA 10 was quickly converted for the flight.

The flight preparations

On July 29, 1918, the 87 Squadriglia received the order to operate. As soon as the weather conditions allowed, the flight could now be carried out at any time. The line was under Gabriele D'Annunzio as the highest ranking officer.

According to the high command, the operation was purely demonstrative in nature, and neither the city nor its inhabitants were to be harmed. The plan of operations stipulated that 14 planes were to fly from the San Pelagio airfield near Padua to Vienna and back in two triangular formations that were slightly offset one above the other . The route chosen for the outbound flight was San Pelagio, Livenza Estuary, Cividale , Triglav , Klagenfurt , Große Saualpe , Bruck , Mürz Valley , Wiener Neustadt , Vienna. The return flight takes a south-eastern route along the southern railway line Vienna - Graz - Trieste and via Grado along the Adriatic coast and Venice back to San Pelagio. All aircraft had to be equipped in such a way that they could be destroyed in the event of an emergency landing. As on his previous enemy flights, D'Annunzio also carried a poison capsule with him in order to avoid being captured. In addition to dropping leaflets, selected destinations such as railway junctions and industrial facilities in Wiener Neustadt should be photographed. In addition to the permanently installed on-board camera, Antonio Locatelli also carried a small handset with which he took pictures of the other aircraft during the flight.

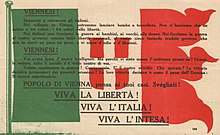

Should Vienna not be reached, the leaflets had to be brought back to the base. A drop elsewhere was strictly forbidden. The texts were written by D'Annunzio and Ugo Ojetti. The latter was since March 1918 commissioner for enemy propaganda in the Italian General Staff. A total of three different leaflets were printed with a print run of almost 400,000 copies. The texts written by Ojetti were also available in German translation, while the text written by D'Annunzio was considered too incomprehensible by the high command and was not translated. Each machine should carry 20 kilograms of leaflets.

The text of the German translation:

Get to know the Italians.

It is said of you that you are intelligent, but since you put on the Prussian uniform you [sic] have sunk down to the level of a Berlin brute [sic], and the whole world has turned against you.

|

Departure was scheduled for August 2 at 5:15 a.m. On August 2nd, 14 planes, 13 single-seat SVA 5 and one double-seat SVA 10 took off as planned, but had to turn back via Udine due to bad weather. Fog broke up on the return flight and the formation broke up as ordered. Some planes went off course and landed in Verona , Ferrara , Bergamo and Bologna , with several machines damaged on landing and failed. On August 5th the squadron was ready for action again. After the weather conditions on August 6th and 7th did not permit any further take-offs, the second attempt at take-off was successful on August 8th with the remaining eleven machines. But even this attempt failed after a few hours of flight due to the bad weather conditions over the Alps. The SVA 5 flown by Ludovico Censi , which took off later due to technical problems, came off course when trying to catch up with the formation and got into severe turbulence, so that the pilot was forced to drop the leaflets he was carrying over enemy territory, which resulted in a surprise effect questioned the whole operation. After the new failed attempt, the high command wanted to cancel the operation because the machines were urgently needed for other tasks. The squadron leader Captain Alberto Masprone and D'Annunzio managed to get a 24-hour delay for one last attempt. Since the high command had ordered that at least five planes had to reach Vienna and otherwise the operation had to be canceled, D'Annunzio assembled the pilots he had chosen, Natale Palli , Antonio Locatelli, Gino Allegri , Aldo Finzi and Piero on August 9, shortly before take-off Massoni around. Aware of this last chance, the group had to swear to accompany him to Vienna in any case.

The flight

On August 9, eleven planes took off at 5:50 a.m. from San Pelagio for Vienna. Shortly afterwards, two aircraft had to turn around due to engine problems, while Captain Masprone's machine had to make an emergency landing. The remaining eight SVA, in addition to the five conspirators, Ludovico Censi, Giordano Granzarolo and Giuseppe Sarti , continued the flight without any problems. At 6:40 a.m., the formation with Palli and D'Annunzio at the head in Caorle was spotted for the first time by Austro-Hungarian observers. Further visual reports followed without any obvious countermeasures being taken. The squadron was noticed by two pilots from a flight school near Klagenfurt. When they made this report, however, they were not believed. From the Saualpe onwards the sky was overcast, which hindered the view of the ground and made navigation difficult, but also reduced the risk of being discovered from the ground. At 8:10 a.m. engine noises were heard between Judenburg and Graz, but the clouds prevented identification of the machines, which had meanwhile reached their maximum flight altitude of 3,650 m.

At Neunkirchen the formation broke through the cloud cover again. Via Wiener Neustadt , the Sarti machine fell back due to a defective injection valve . Sarti managed to block the fuel supply and thus prevent a fire, but had to make an emergency landing. During the emergency landing near Schwarzau am Steinfeld , SVA 5 overturned. Sarti was largely uninjured and was just able to leave his plane and set it on fire before he was picked up by gendarmes. Around 9 o'clock the sun tore open the high fog and a quarter of an hour later Vienna appeared before the eyes of the eight remaining planes. At 9:20 am the seven machines with Natale Palli and Gabriele D'Annunzio, Antonio Locatelli, Gino Allegri, Aldo Finzi, Pietro Massoni, Ludovico Censi and Giordano Granzarolo were over the city area. Before the squadron flew over the Vienna outskirts Hietzing and Meidling , Palli had already given the signal to dive .

About Vienna

The flight over Vienna's urban area at a height of about 600 m took around 20 minutes without the formation encountering any resistance. The anti-aircraft battery on the Rosenhügel had only identified the machines as Italian aircraft when they were out of range again. A report sent from Carinthia at 7.45 a.m. did not reach the squadron stationed at the Wiener Neustadt airfield until 10:20 a.m. The latter had been informed of the Italian planes at 9:35 a.m. after they were already over Vienna. At 9:50 a.m. the command of the anti-aircraft service triggered the alarm and at 10:05 a.m. some fighters took off from Wiener Neustadt when the Italian aircraft on their return flight had again disappeared behind clouds.

The squadron around Gabriele D'Annunzio had in the meantime dropped the leaflets they had carried with them and made numerous aerial photos of the city area, which was flown over from west to east. Along this route, leaflets were dropped about Hietzing, Schönbrunn , Meidling, Westbahnhof , Mariahilfer Strasse and the city center. The leaflets were collected and destroyed by the authorities, distribution made a criminal offense and the population called upon to hand in leaflets to the police if they came into their possession.

The flight back

After 20 minutes, the return flight was taken at 9:40 a.m. It first went along the Danube to Schwechat , before the formation followed the tracks of the southern Graz – Ljubljana – Trieste railway as ordered. Strong tail wind supported the way back. There was still no sign of Austro-Hungarian fighter pilots. If enemy planes appear, according to the operational order, an aerial combat should be avoided and the superior speed of the SVA should be used. The previously overcast sky cleared over Ljubljana and the Austro-Hungarian air defense made itself felt for the first time over Haidenschaft . The flak and machine gun fire did not cause any damage. Before Trieste, Palli and D'Annunzio's engine suffered brief engine failures. When they reached Trieste, two seaplanes took up chase but failed to reach the faster SVA. During the flight along the Adriatic coast , the first Italian torpedo boats were encountered , which were supposed to provide help in an emergency. The squadron was shot at for the last time over Grado . Venice was flown over around noon and at 12:36 p.m. all seven planes landed back in San Pelagio after a flight of over six and a half hours.

Reactions

The first enemy flight of an Entente power over a capital of the Central Powers triggered a great deal of press coverage. The foreign press such as the Times or the Daily Telegraph also praised the company.

But there were also critical voices in Italy. In a parliamentary question, the dropping of leaflets instead of bombs was criticized, whereupon the War Ministry was prompted to issue a statement, which was entrusted to Commander-in-Chief Diaz . This again underlined the purely demonstrative character of the company with which the superiority over the opponent should be underlined. The background to the request was the repeated Austro-Hungarian air raids on Venice and the bombing of LZ 104 on Naples . The high command also emphasized that taking a bomb would have been limited to one 20 kg bomb and that the military success in the case would have been insignificant.

On the Austrian side, the flight triggered a general alarm mood and a series of investigations from the highest authorities. In particular, it was about clarifying how the enemy planes could appear over Vienna without the city being put on alert beforehand.

The Arbeiter-Zeitung from Vienna also praised the excellent performance of the Italian pilots and paid tribute to them. In particular, the performance of the completely unmilitary D'Annunzio was highlighted. He would have deliberately exposed himself to the dangers of death, in contrast to many Austrian poets in the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian Army , who in the past gladly condemned him for his empty phrases.

literature

- Giorgio Apostolo: I preparativi dell'impresa . In: Gregory Alegi (ed.): In volo per Vienna , Museo dell'aeronautica Gianni Caproni , Museo storico italiano della Guerra , Trient 1998.

- Carlo Piola Caselli: Gabriele d'Annunzio e gli eroi di San Pelagio , Amazon, undated , undated ISBN 978-1-5193-0505-3 .

- Baldassare Catalanotto: Il volo su Vienna . In: Gregory Alegi (ed.): In volo per Vienna , Museo dell'aeronautica Gianni Caproni, Museo storico italiano della Guerra, Trient 1998.

- Fondazione Il Vittoriale degli Italiani (Ed.): D'Annunzio poeta avviatore. Storia di un volo , o. O., o. J.

- Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio: da poeta a dandy a eroe di guerra e comandante , Gaspari, Udine 2001 ISBN 978-88-86338-72-1 .

- Museo dell'Aeronautica Gianni Caproni (ed.): Gabriele D'Annunzio avviatore , Museo dell'aeronautica Gianni Caproni, Trento 2014, ISBN 978-88-96853-03-0 .

- Erwin Pitsch: Italy's grip over the Alps: The air raids on Vienna and Tyrol, in the first World War . Karolinger Verlag, Vienna 1994 ISBN 978-3-85418-066-1 .

- Bernhard Tötschinger: Il volo di D'Annunzio visto da Vienna . In: Gregory Alegi (ed.): In volo per Vienna , Museo dell'aeronautica Gianni Caproni, Museo storico italiano della Guerra, Trient 1998.

Web links

- Ikarus on Vienna - Der Standard from September 13, 2002, accessed on December 27, 2017

- D'Annunzio's flight over Vienna (1918) accessed on December 27, 2017

- Myth Gabriele D'Annunzio - Austrian State Archives Retrieved on December 27, 2017

- Retrieved on December 27, 2017 via Aviatisches d'Annunzio, Marinetti, the avant-garde and fascism

Individual evidence

- ^ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 52-87

- ↑ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , p. 100, 189-190

- ↑ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 109-120

- ↑ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 189–190

- ↑ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 192-196

- ^ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 257-264

- ^ Giorgio Apostolo: I preparativi dell'impresa , pp. 66-67

- ^ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 261–262

- ↑ Museo dell'Aeronautica Gianni Caproni (ed.): Gabriele D'Annunzio avviatore , p. 258

- ^ Austrian State Archives , accessed on December 27, 2017.

- ↑ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 265-267

- ↑ Baldassare Catalanotto: Il volo su Vienna , pp. 79–80

- ↑ Baldassare Catalanotto: Il volo su Vienna , p. 81

- ^ Bernhard Tötschinger: Il volo di D'Annunzio visto da Vienna , p. 215

- ↑ Neues Wiener Abendblatt dated August 9, 1918 , accessed on January 11, 2018

- ↑ Baldassare Catalanotto: Il volo su Vienna , pp. 82–83

- ^ Vittorio Martinelli: La guerra di D'Annunzio , pp. 279-280

- ↑ Bernhard Tötschinger: Il volo di D'Annunzio visto da Vienna , pp. 216-219

- ↑ Arbeiter-Zeitung, August 10, 1918, pp. 2-3 , accessed on January 11, 2018

- ↑ Arbeiter-Zeitung of August 11, 1918, p. 6 , accessed on January 11, 2018