Battle of Vittorio Veneto

1915

1st Isonzo - 2nd Isonzo - 3rd Isonzo - 4th Isonzo - Lavarone (1915-1916)

1916

5th Isonzo - South Tyrol offensive - 6th Isonzo - Doberdò - 7. Isonzo - 8. Isonzo - 9th Isonzo -

First Dolomites Offensive - Second Dolomites offensive -

Avalanche disaster

1917

10th Isonzo - Ortigara - 11th Isonzo - 12th Isonzo - Pozzuolo - Monte Grappa

1918

Piave - San Matteo - Vittorio Veneto

The Battle of Vittorio Veneto (or "Third Piave Battle ") was fought towards the end of the First World War from October 24, 1918 to November 3 or 4, 1918 on the Italian front in northeast Italy. It led to the armistice of Villa Giusti near Padua and to the defeat of Austria-Hungary in the war against Italy .

Situation in the spring of 1918

In the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo (also Battle of Karfreit October / November 1917) Austria-Hungary and Germany succeeded in defeating the Italians in the Julian Alps and forcing them to retreat from the Isonzo to the Piave . On Monte Grappa and the Piave, the advance of the Central Powers came to a halt partly because of the Italian resistance on the Grappa cornerstone, partly because of the bad weather and the flooding Piave, and partly because of their own hesitations (First Piave Battle , December 1917). After the Battle of Karfreit, the Italian army was inferior to its opponent in terms of troop numbers due to the high losses (56 to 65 divisions) and had to be reinforced by troops brought in from the western front .

From March 1918, Great Britain and France had a total of five divisions in Italy, plus a Czech division and an American regiment , some of which consisted of Italian emigrants. In return, an Italian corps with two divisions was sent to the western front to repel the German spring offensive on the western front. In addition, the French army command had over 70,000 Italian workers who were under military jurisdiction to secure French supplies.

In view of the increasing problems of their own, Austria-Hungary tried in the Second Battle of the Piave in June 1918 to defeat Italy definitively and to end the war as quickly as possible. This failed because of the Italian resistance. At the latest since the Second Battle of the Piave in June 1918, the Italians recognized and used the advantage that the Austrians had during the entire war: the enormous defensive effect of the new machine weapons (MG), especially when they fired from elevated positions and one frontal attackers caught in the flank. Basically, the Italian leadership wanted a new major Austrian attack, as in June 1918, in order to launch a long-planned, decisive counterattack on such an occasion.

Military situation in the summer of 1918

After the defensive success on the Piave, the French Commander-in-Chief Marshal Ferdinand Foch demanded an early counter-offensive from the Italian Supreme Command (Comando Supremo). Of the 300,000 US soldiers who arrived in France every month (from June 1918) and decided the war on the Western Front, Foch did not want to deliver any further reinforcements to Italy. The military situation in Italy in the late summer of 1918 was nowhere near as superior as the western Entente imagined. From July to October 1918, the war on the Italian front continued with great intensity. In the summer there was heavy fighting, including on the Monte Mantello, the Monte Cornone, the Col Tasson, the Monte Corno and the Col del Rosso. Fighting battles took place until October from the Swiss border to the Adriatic Sea , which sometimes developed into heavy fighting in various places, for example at Papadopoli on the Piave, on the Grappa massif and on the Asiago plateau . The operations of the air forces on both sides were also remarkable. Italian airmen repeatedly bombed the naval port of Pola and other Austrian bases in Dalmatia . In addition, attacks were also made east of the Piave, including Villach and Lienz . A squadron under the command of Gabriele d'Annunzio flew to Vienna in August 1918 and dropped almost 400,000 leaflets over the city. The Austrian airmen bombed targets between Ravenna and Rimini , Treviso , Padua and Venice were repeatedly targets of Austrian air raids, mainly at the end of August 1918.

There was cause for optimism because of the successes of the Entente in France, where the Germans suffered heavy defeats in July and August 1918, and also because of the situation of Austria-Hungary, especially its army , which suffered more and more from supply problems, desertions and general emaciation . In view of the defeats of the Central Powers on the other fronts and the demands of Ludendorff and others for an armistice , a quick decisive battle was called for, for which the plans were worked out in late September and early October.

Overall, despite all concerns, the development seemed to justify the risk of an Italian attack. Politically and temporally, an attack in October 1918 seemed well chosen from an Italian perspective. Foch's strategic decision not to support Italy and to leave the focus on the western front was militarily questionable. Because the rapid concentration on the weaker Austria-Hungary and a possible subsequent threat to Germany from the south might have forced Berlin to surrender faster and more sustainably than through an offensive on the Franco-Belgian front. Politically, Foch's decision was correct in the interests of France, since the Italian front was under no circumstances intended to play a role that would detrimental to French prestige. Conversely, one could say something similar about Germany and Austria-Hungary about the southern front. The Italians feared such a strategic decision until the very end.

Military planning and deployment

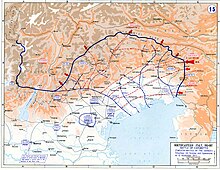

In early September 1918, the Italian leadership began planning a limited attack in the lowlands. One thought of a bridgehead east of the Piave, between Monte Cesen and Susegana, from where a major offensive was to be launched in the spring of 1919. These plans were soon abandoned due to pressure from the other Entente powers and the Italian government. The new objective of the Italian high command under General Armando Diaz , the chief of the general staff, was to achieve a separation of the Austrian forces in Trentino from those on the lower Piave . Reaching the traffic junction of Vittorio Veneto not only meant separating the Tyrolean Army Group ( Austro-Hungarian 10th and 11th Army under Archduke Joseph ) from the Boroevic Army Group ( Austro-Hungarian 6th Army and so-called Isonzo Army ) in the Venetian lowlands also paralyze the enemy’s supply lines. In order to make the Italian advance on Vittorio Veneto possible, the Piave should be attacked at the most critical point of the enemy, namely at the border between his 5th and 6th Army. The separation by a sickle-like cut on Vittorio Veneto (which at that time was still called Vittorio, it only got the addition in 1923) and furthermore the Austrian mountain front (which was a constant threat to the Italian associations in the lowlands southeast of Monte Grappa ) should collapse and subsequently, in the absence of connections to the north, the Piavefront in the lowlands.

The Austro - Hungarian 6th Army ( General of the Infantry Alois von Schönburg-Hartenstein ), which was in the main field of attack of the Italian 8th Army under General Enrico Caviglia and stopped between Pederobba and Ponte della Priula on the Piave, relied on the strategically most unfavorable supply line (Vittorio Veneto - Conegliano - Sacile ). Of standing at the front Grappa Italian 4th Army under General Gaetano Giardino was Feltre assigned as a target, so the area in back of the defending there Austrian army group Belluno ( FCM Ferdinand Goglia ). This cut off the opposing associations and reached the Val Cismon and Valsugana valleys . Then they wanted to advance north via the Cadore Valley ( Belluno ) and thereby roll up the entire Austrian front in Trentino.

The Italian units were extensively prepared for this attack, in particular for the difficult crossing of the Piave, which was flooded in October (as in 1917 to Karfreit) and for holding large bridgeheads east of the river (in order to prevent difficult retreat battles like that of the Austrians in June 1918 ). Special attention was also paid to supplies. In order to better manage the large units, new army commands were set up between the Brenta and Piave estuaries in mid-October , including the 12th Army under French command under General Jean-César Graziani and the English 10 Army under General Frederick Lambert Earl of Cavan , the Commander in Chief of the British Forces in Italy.

Until October 15, all Italian troop movements took place almost exclusively at night and in strict secrecy. The attack could finally begin on October 15, but the constant rain and flooding forced another postponement. On October 18, the weather deteriorated so much that a postponement of a week became inevitable. Due to the impending snowfall, the entire company threatened to become impracticable.

On the Austrian side there were 55 infantry divisions and 6 cavalry divisions . On the Italian side there were a total of 57 divisions , three of which were British and two French. There was also a US regiment.

On October 20, the Austrian side had troops marching in anticipation of the Italian attack, and they arrived four days later at the start of the battle. Considerations of tactically withdrawing behind one's own national borders had become obsolete because of the advanced times.

Course of the battle

First phase of attack

Italian artillery fire began between Brenta and Piave on October 24, 1918 at 3:00 a.m. (anniversary of the Battle of Good Friday 1917). At 7:15 am, the infantry attacked in fog and then rain. The weather conditions made artillery fire difficult on both sides, but not close combat by the infantry . The attack on the Piave section was not scheduled for the night of October 25, but weather conditions made it necessary to postpone it for several days. In the early morning hours of October 24th, however, British (advance guard battalion of the 7th Division under Lieutenant Colonel Richard O'Connor ) and Italian troops at Papadopoli occupied some of the Piave Islands according to orders. Between Pederobba and Sant'Andrea di Barbarana, the water level in the otherwise flattest places was around two meters, and the water flowed at over three meters per second. In the meantime they fought on the Grappa massif for the Col della Berretta, the Monte Pertica, the Monte Asolone and others, not without consequences for the Austrians, who now concentrated their reserves there.

On the Grappa massif , where the main thrust initially took place, the Italians first occupied Monte Asolone, from which they had to withdraw again due to Austrian counter-attacks. Similar scenes took place on Monte Pertica and Monte Pressolan. The Italian high command had the attacks on the grappa stick repeated over and over again in order to tie up Austrian troops there, who could not be deployed on the Piave.

On the evening of October 24th, the first major refusals of orders occurred on the Tyrolean front on the plateau of the seven municipalities . Hungarian units of the 27th Division (Major General Sallagar ) and the 38th Honved Division (Major General Molnar ) refused to move into the front at Asiago .

On the evening of October 26th, the Italian pioneers began building eleven bridges over the Piave (Molinello, seven between Fontana del Buoro and Priula, three near Papadopoli). Between Vidor and Nervesa, in the area of the two Italian storm divisions, some bridges could not be built due to the flood and the Austrian artillery fire.

The attack phase on the middle Piave

On the morning of October 27th, the French XII. Corps (General Graziani) at Pederobba , the Italian XXVII. Corps (General Antonino Di Giorgio ) at Sernaglia and the English XIV. Corps (General John M. Babington ) and Italian XXIII. Corps at Cimadolmo (Papadopoli sector ) three bridgeheads on the opposite bank of the Piave. The Piave could only be crossed on a total of six bridges, otherwise boats were used. Shortly afterwards, the floods and the Austrian artillery destroyed several bridges, a circumstance that put the not yet consolidated bridgeheads in considerable distress. Nevertheless, they could be expanded to the north and west. While the units of the Austro-Hungarian II Corps opposite under General der Infanterie Rudolf Krauss showed little resistance, the kuk XXIV Corps under FML Emmerich Hadfy held its positions, especially the Hungarian 51st Honved Division under Major General Daubner thwarted all Italian efforts at Nervesa, to come across the river. Between Falzè and Nervesa, in the section of the Italian VIII Corps under General Asclepia Gandolfo , it was again not possible to build a bridge by the end of the day, which led to a gap between the 8th and 10th Italian armies on the north bank of the river.

The counter-attack ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Austro-Hungarian Army Group on the Piave, Colonel-General Svetozar Boroëvić, failed because the troops concerned refused to give orders - from now on a persistent problem for the Austrian side. On October 27th, in the area of the Austro-Hungarian 6th Army, the Hungarian Feldjäger Battalion 24 of the 34th Division refused to relieve the hard-pressed section of the Austro-Hungarian II Corps. After the other units of the 34th Division had also mutinied, an important counterattack in the Soligo Basin could not be launched.

Throughout October 28th, the Italians worked on their bridges and fought against the floods and the Austrian artillery fire (partly gas attacks). The right wing of the Italian 8th Army tried from Montello to gain the other bank; The resistance of the kuk XXIV Corps could not be broken immediately despite great efforts. The 11th Honved Cavalry Division and the 12th Rifle Division were pushed back to 10 km width. The Austro-Hungarian 25th Division had to give up the heights of Farra di Soligo and go back to the Bigolino-Cobertaldo-Farra line.

The complete Italian XVIII. Corps under General Luigi Basso was sent over the bridges of the 10th Army to advance on Conegliano and thus to enable the VIIIth Corps of the Central 8th Army to cross the river and advance on October 29th. The rubble of the 31st division belonging to the kuk II Corps had to give up the heights north of Valdobbiadene and were withdrawn via San Pietro to Follina.

The counterattacks of the kuk 12th rifle division can strengthen the Italians by the XXII. Corps under General Giuseppe Vaccari in the middle bridgehead at Sernaglia no longer prevented. The 51st Honved Division, which had so far rejected the transition attempts of the Italian VIII Corps at Nervesa, had to go back to the Marcatelli-Susegana line because of its open flank. The use of the group of the FML von Nöhring , which was positioned as an intervention reserve before the battle, did not take place at all because of refusals of orders by the 36th and 43rd (rifle) divisions. The troops of the kuk XVI that were still standing at Vazzola . Corps (General of the Infantry Rudolf Králíček , interim under FML Otto von Berndt ), the 29th Division and the 201st Landsturm Brigade as well as the remnants of the 7th Division (FML von Baumgartner), which had been defeated by the British the day before, had to move behind the Withdraw Monticanobach.

On October 29th, the Italian 8th Army and, east of it, the 10th Army had formed major bridgeheads. After the deployment of the Corpo d'armata d'assalto (Assault Corps) under General Francesco Grazioli, the Italians succeeded in separating the Austrian units and on October 30th also in the advance on Vittorio ( renamed Vittorio Veneto due to this battle in 1923 ). In the mountains, too, a breakthrough was achieved near Quero, despite the Austrian resistance and the difficult terrain.

Offensive on the grappa section

The kuk XXVI began on the Grappa massif. Corps under General of the Infantry Ernst Horsetzky launched a counter-offensive on October 27th. The Austrian troops fought on the Grappa massif with the aim of breaking through from Grappa into the lowlands and rolling up the Italian Piavefront from behind. Eight attacks on Monte Pertica were repulsed by the Italian 4th Army (VI., IX. And XXX. Corps) in six hours of combat. There were great losses on both sides. On the following two days there was also heavy fighting with artillery deployments.

On October 30th, the Austrian resistance collapsed on the lower Piave, whereupon the Italians pushed ahead according to their plan and brought the Austrian associations fighting on the Grappa into an untenable situation. Threatened by being surrounded, the Austrians, under Feldzeugmeister Ferdinand von Goglia , withdrew from grappa on the night of October 30th to 31st.

Final stage of the battle

At the mouth of the Piave, the 3rd Italian Army (XXVI. And XXVIII. Corps), which was under the command of Duke Emanuel of Aosta , received the order to attack. After initial resistance by the Austrian Isonzo Army (Imperial and Royal IV, VII, XXII and XXIII Corps) under Colonel General von Wurm , the Italian advance could not be stopped. By November 1, the Italians had reached roughly the Asiago - Feltre - Belluno line in the west , and crossed the Livenza , the parallel river to the Piave , in the east . Until November 4th, large parts of Friuli and Trentino were in Italian hands. The line of occupation in accordance with the armistice then ran along the main Alpine ridge .

Political and military collapse of Austria-Hungary

The political situation in the multi-ethnic state Austria-Hungary became more and more acute. On October 24th, faced with the lost war, the Hungarian government called back its troops to defend Hungary, which was threatened with invasion from the southeast. This affected the Czech and other troops of the multi-ethnic state. German-Austrian troops continued to fight, but could not fill the gaps created by withdrawing Hungarians.

The Italian victory of Vittorio Veneto sealed the end of Austria-Hungary, which ceased to exist on October 31, 1918 with Hungary's exit , after Czechoslovakia and Croatia had already declared their independence on October 28 and 29 (confirmation under international law on October 10 , 1918) September 1919 in the Treaty of Saint-Germain , entered into force on July 16, 1920).

Commemoration

- In memory of the battle, ships were given the name Vittorio Veneto .

- Streets in Rome were named after this victory: Via Vittorio Veneto, or Via Veneto for short , and Via Quattro Novembre.

Individual evidence

- ^ David Stevenson, With our backs to the wall. Victory and defeat in 1918 , ISBN 978-0-7139-9840-5 , Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 157: "According to Austrian sources, on the eve of the battle the Austro-Hungarian forces comprised 55 infantry and 6 cavalry divisions " Google Book

- ↑ Michael Duffy: Depiction of the battle (English)

- ^ A b c David Stevenson, With our backs to the wall. Victory and defeat in 1918 , ISBN 978-0-7139-9840-5 , Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 160 Google-books

- ↑ a b c d cf. US map to battle

- ↑ Cf. Heinz von Lichem : War in the Alps 1915-1918. Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1993. Volume 3, pp. 348-350: With Italy's advance in the lowlands, the Grappa front was now bypassed and threatened to be encircled by the simultaneous Italian advance to Feltre.

literature

- Austria-Hungary's last war. Volume 8, Verlag der Militärwissenschaftlichen Mitteilungen, Vienna 1938.

- Anton Wagner: The First World War. Troop service paperback, Ueberreuter, Vienna 1981.

- Pier Paolo Cervone: Vittorio Veneto. L'ultima battaglia. Mursia, Milan 1994.

- Manfried Rauchsteiner : The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1993.