Austria-Hungary's army in the First World War

The article Austria-Hungary's Army in World War I describes the land forces of Austria-Hungary 1867–1914 at the outbreak and during the First World War (1914–1918) as well as the most important war events in which they were involved.

State of the army and preparation for war

Of the armies of the major European powers , the army of Austria-Hungary was the least prepared for war. Austria-Hungary had an industrial to small base for the modern equipment of his troops, even if selectively top products were manufactured, such as the mortar of Škoda . The Austrian production of artillery shells never exceeded a million pieces per year, while the Russian factories were already producing four million pieces in 1916. The armed forces were only gradually equipped with contemporary war equipment. The logistics were underdeveloped, so that there were often supply problems. The speed of deployment of the troops was hampered by the inadequate infrastructure . The military specialists often lagged behind even the civil railway company. While the state railway ran with up to 100 wagons per train , the military only allowed up to 50 wagons to be merged. The military rail link between Vienna and the San was three times slower than that of the civil rail company.

The armament with infantry weapons and artillery guns was contemporary, but only with regard to the standing army. For the reserves in the event of mobilization, only outdated equipment was available for the most part - so when the standing rifles were set up in 1915 they had to bring their rifles with them or were initially equipped with the ancient, single-shot Werndl rifles . The same applied to the artillery, which was disproportionately equipped in the reserve with old cannons without a return barrel. Reasons were the lack of financial resources and the attitude [...] you should throw away all the beautiful (and expensive) things - you will certainly be able to use them again [...] , which led to the well-known (fatal) results. Ultimately, they were even forced to use some of the M 61/95 fortress guns long forgotten in the casemates of the Theresienstadt fortress on wooden post mounts during the mountain war in the Dolomites.

The level of the troops showed serious weaknesses, which can also be traced back to the character of the dual monarchy as a multi-ethnic state . Most officers were recruited from the German and Hungarian national people, but the men from all parts of the population. German was the language of command, but the simple, non-German-speaking soldier was only taught about one hundred words (Beware, rest, rifle in hand) , which were absolutely necessary for duty. Naturally, these circumstances did not have a positive effect on the cohesion and morale of the troops. According to the last pre-war statistics from 1911, 72% of the active professional officers in the infantry, 67% in the cavalry and 88% in the artillery described themselves as Germans.

Far-reaching reforms were urgently needed, but were only half-heartedly considered and repeatedly postponed. One of the reasons was the permanent neglect of the largest body of troops, the Joint Army . When, after the so-called Compromise of 1867, Hungary had to be granted its own army in order to keep the country in the Reichsverbund, the Hungarians immediately began to raise an army that was euphemistically called the ku Landwehr (Honvéd) . Initially consisting only of infantry, this Landwehr then also received its own cavalry and artillery units; the Hungarian administration preferred them in allocating money and staff. For reasons of parity, the rest of the empire received a Landwehr, which in turn was treated with the greatest benevolence by the administration of the other half of the empire. (The five regiments of the Imperial and Royal Mountain Troops belonging to the Imperial and Royal Landwehr were among the best in the entire “armed force”.) This all came at the expense of the main army, whose recruits were sometimes so small that the new machine gun units had to be deployed 4. Battalions of the infantry regiments had to be thinned out in places down to one cadre.

Overall, Austria-Hungary was in a position to endure a conflict like the First World War for a long time in terms of personnel, but not materially.

Personal equipment (mount)

The first supply problems began as early as 1914. A lack of stocks and the fact that industry was not prepared for this type of mass production led to an extreme shortage of uniforms (pieces of clothing); a constant shortage persisted until the end of the war.

Inadequate production volumes caused the greatest headache for the military administration. The additional Landsturm and the first marching battalions were dependent on what the units leaving the field had left behind in the clothing depots. The total stock of pike-gray uniforms in the clothing depots in 1914 should have been around 700,000, plus around 300,000 peace and parade uniforms, which were only partially usable. At the beginning of the war, shoes were not available in sufficient quantities and even with the greatest efforts they could not be obtained. The commanders of the VI. and VII. Marching formations were instructed to buy the footwear on the free market. However, the material procured in the process rarely met the requirements.

The situation was even more precarious for equipping the Landsturm. Intended for service in the hinterland, the Landsturm was only to be adjusted with blue peace uniforms. However, when the high personnel losses in the course of the war made it necessary to send Landsturm formations into the trenches, these men found themselves on the front line at the beginning of the war in their blue uniforms (or even in civilian clothes with a black and yellow armband). The change in the pike-gray outfit proceeded very slowly, as the active troops were given priority. Another endurance test for the outfit administration came after Italy declared war in May 1915 (Italy had given up its previous neutrality; more here ): the stand riflemen from Tyrol and Vorarlberg as well as the Styrian and Carinthian volunteer riflemen had to be called to the border guard ; these 39,000 or so men could not be fully clothed immediately either. The Standschützen from Hall in Tirol moved out in civilian clothes, the Predazzo company could initially only be equipped with the peace uniforms of the Landwehr.

The general supply difficulties also contributed to the fact that the standardized colors of the field uniforms could no longer be adhered to in the course of the war and the colors differed greatly in some cases. (In addition to the mandatory pike gray, there were dark gray, gray-green and brown shades.)

Strategy and planning

At the beginning of the war in 1914, the army was not only in terms of its material equipment, but also of its strategic and tactical concept, which it should have been in order to cope with the potential opponents. The reason for this was the clinging to traditional ideas ( steadfast until death - the result was unnecessary loss of personnel and material) instead of giving up terrain for tactical reasons. The lessons of the war of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 were adhered to (the training regulations for infantry troops issued in 1911 and strongly influenced by the chief of staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf , were a good example of this type of attitude) and ignored the further developments in weapons technology (e.g. aircraft, tanks, explosive grenades ) and military tactics ; these had become clear in the conflicts between Russia and Japan in 1905, in the Bosnia crisis, which was militarily settled by Austria-Hungary itself, in 1908, and in the Balkan wars of 1912/1913.

The handbook for the study of tactics, also written by Conrad von Hötzendorf (1st part published in 1891), stood for the basic idea of the Austro-Hungarian military command: offensive and attack - at any price. This doctrine was also practiced by many other warring parties ( glorified in France as the offensive à outrance ). The result of this attitude were the enormous losses that the peace tribe of the Army in Galicia suffered and which could not be replaced. The fact that one was facing two armies ( Russia and Serbia ) which had already been involved in major combat operations in the 20th century and which had already modernized their strategic and tactical orientations had been ignored .

Only two countries came into question as opponents in the General Staff's war plans : Russia or Serbia together with Montenegro . Two deployment plans had been drawn up for this purpose. Plan “R” (Russia) dealt with the war on two fronts and Plan “B” ( Balkans ) only dealt with the war against Serbia and Montenegro. In the event of war "R" the main force of the army with the so-called squadron "A" (consisting of nine corps and ten cavalry troop divisions) had to attack Galicia from Russia. The so-called “B” squadron of four corps and a cavalry division was supposed to advance. Only the minimal Balkan group with three corps would be available against Serbia and Montenegro . In the case of "B", the troops of the "B" squadron, reinforced by the three corps of the minimal group Balkans and four cavalry troop divisions, should be deployed.

Although it was foreseeable that Russia would not remain inactive, since the alliance treaties between Serbia and Russia were known, Austria-Hungary responded in response to the Serbian mobilization of July 25, 1914 only with the partial mobilization and then to Serbia on July 28th Once war was declared, Plan "B" was put into effect. After the general mobilization of Russia on July 30, 1914, Plan "R" should have been implemented immediately; however, this did not happen. There were no preparations for stopping or changing a mobilization process that had already started. The "B" relay, which initially continues to roll to the Serbian front, would have been urgently needed in Galicia. It was not until July 31, 1914, the day of general mobilization, that the monarch installed the army high command .

The Kingdom of Italy did not comply with its alliance treaty (concluded in 1882 with Austria-Hungary and the German Empire ) on the grounds that it was formally a defensive alliance . It initially declared itself neutral and made territorial claims for parts of Austria-Hungary (southern Tyrol with Trento to the Brenner border according to the ideas of Ettore Tolomei (1865-1952), as well as the Italian-speaking areas of the Austrian coastal country, especially Trieste ).

Austria-Hungary was only willing to negotiate with regard to the Italian-speaking areas of present-day Trentino. Moderate supporters of the Irredenta (including the Reichstag deputy Cesare Battisti , who moved to Italy at the beginning of the war, became an officer there and was hanged for high treason after his capture), on the other hand, spoke out in favor of drawing a boundary at the Salurner Klause , but could not prevail.

At that time, however, it was not possible to protect the border, which was already threatened, with the exception of the permanent fortifications with noteworthy troops.

General mobilization

On July 25, 1914 signed Emperor Franz Joseph I. command for partial mobilization, which the board on July 31, 1914 mobilization of the armed force or armed forces was followed by armed forces of the monarchy above. These are made up of:

- of the Joint Army

- of the Imperial and Royal Landwehr

- the Royal Hungarian Landwehr

- the kuk Kriegsmarine

The army high command formed for the war under Archduke Friedrich von Österreich-Teschen as high commander and Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf as chief of staff was the highest authority for the entire land and naval forces of the monarchy .

The target peace level of the army and the two land forces was:

- 25,000 officers (not including doctors, veterinarians and accounting officers )

- 410,000 NCOs and men

- 87,000 horses (here the information varies)

- 1,200 guns (only active, field-movable guns - not including fortress guns and reserve stocks)

The workforce included 36,000 so-called gagists - long-term service and professional soldiers .

The peace establishment was involvement of the recruits the vintage 1914 (birth year 1893) to 3.35 million men mobilization status brought. There were also the first marching battalions and additional land storm formations.

The military strength of the land forces in 1914 was:

- 1,094 infantry - battalions (including 117 marching and 200 militia battalions)

- 6 cycling companies

- 425 cavalry - squadrons

- 15 aviation companies

- 483 artillery - Batteries

- 224 fortress artillery companies

- 155 technical companies ( pioneers , sappers , railway and telegraph troops )

- 8 Landsturm sapper departments

- 88 Landsturm artillery divisions

- 28 bridge protection companies

- in addition there are train , catering , medical , staff and liaison troops as well as columns and workers' formations raised on site. It can be assumed that there will be a supply of 1.8–2 million men in the field.

Army clothing and equipment corresponded to the state of the art at the time. However, this only affected the active, fighting units. The Landsturm (deployed for guard duties, for example) was still partly dressed in blue peace uniforms. The infantry wore the pike-gray marching adjustment (which later turned out to be too light and was replaced by a gray-green outfit based on the German model) a cap and as a weapon the Mannlicher rifle or the Schwarzlose model MG 07/12 machine gun. Cavalry and artillery moved out in their colorful peace uniforms, whereby only the shiny helmet parts of the cavalrymen were covered by a cover or simply painted over with gray paint.

Contrary to all pessimistic statements, separatist currents faded into the background with the mobilization . Czechs, Hungarians, Bosniaks and also Italian-speaking subjects of the crown submitted to the monarch's call without contradiction.

War year 1914

In order to relieve the German ally, who had to give up large parts of East Prussia after the battle of Gumbinnen , the army high command decided to attack north from Galicia. The aim was also to anticipate the Russian deployment. The 1st Army under General of the Cavalry Dankl and the 4th Army under General of the Infantry Auffenberg were able to defeat the Russian forces at Krasnik and Komarow . The 3rd Army had to withdraw again at Zloczow after unsuccessful attacks. Despite the second Army ("B" squadron), which was now rolling in from the Balkans as reinforcement , it was not possible to stabilize the situation in the battle of Lemberg ; Lemberg had to be given up. Even after the defeat at Tannenberg , the pressure of the Russian army in Galicia did not ease. The north-facing 4th Army was then ordered to turn around and attack south (near Rawaruska ), while the 2nd and 3rd Armies were to attack northwards at the same time. This so-called second battle near Lemberg ended in disaster and led to the retreat of the Austrians towards the San and western Carpathians .

There were high casualties in these battles. B. with Kaiserjäger and Landesschützen . The 2nd Tyrolean Kaiserjäger Regiment suffered 80% failures. This 2nd regiment lost its flag at Hujcze-Zaborze on September 7th when all the men from the flag command had fallen. (On January 22nd, 1915, the regiment in Dubno was given a new flag by the emperor) The losses of well-trained soldiers of the "peacetime", especially officers, could hardly be replaced - later, with the start of the Alpine war against Italy, this was to be particularly evident the loss of well-trained mountain troops in the early mass battles on the Eastern Front were devastating.

In mid-September, large parts of Galicia were lost and the Przemyśl fortress was enclosed for the first time. Relief attempts were initially unsuccessful until the battle of Limanowa-Lapanow (December 1 to December 14, 1914) weakened the Russian attack force and the front stabilized for the time being.

After the situation on the southeast front against Serbia had calmed down in December 1914, the high command was able to transfer troops to the northeast front in order to strengthen the defensive front on the Carpathian passes. At the end of the year, the Austro-Hungarian associations lost a total of 1,268,696 men killed, wounded and missing (including those who were taken prisoner). Only 863,000 men were replaced; Troops with 30 to 40% actual strength were not uncommon.

Cavalry battle

On August 21, the likely last classical equestrian battle in world history took place east of Zloczów . Here met the Russian 10th Cavalry Division with the 10th Hussar Regiment (Ingermanland Hussars), the 10th Uhlan Regiment ( Odessa- Ulanen), the 4th Cossack Regiment ( Orenburg- Cossack) and the 10th Dragoons Regiment ( Novgorod -Dragoner) to Wołczkowce , which was held by the 2nd Battalion of the kk Landwehr Infantry Regiment No. 35. The attacking Russians were stopped by the 4th Imperial and Royal Cavalry Division with the Dragoon Regiments No. 9 and No. 15 and the Uhlan Regiments No. 1 and No. 13 around the town of Jaroslawice in long battles and attacks by squadrons before the river Strypa (see also Otto Aloys Graf Huyn ).

Southeast front

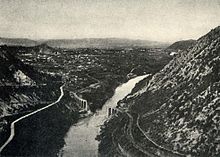

Operations in the Balkans were also unsuccessful. After two offensives by the 5th and Austro-Hungarian 6th Army in August and September 1914 on the Save and in the Battle of the Drina had failed with heavy losses, Belgrade was captured in the third attempt at the beginning of December ; after a Serbian counter-offensive, however, the city had to be evacuated a little later. In addition to the bitter resistance of the enemy, the failures were due to difficult terrain, insufficient supplies and the operational and tactical errors of the commander-in-chief of the Balkan armed forces , Feldzeugmeister Potiorek .

Assaults against the civilian population

In Galicia and Bosnia, many civilians from their own population were executed by the army without trial. Estimates suggest up to 60,000 victims. The allegations were "Russophile" tendencies, "espionage" and "collaboration" with the enemy. The “punitive actions” and reprisals against the civilian population took on such drastic proportions that one can speak of a systematic war against the civilian population. How many civilian casualties this war claimed is still unknown today. Contemporary reports speak for the k. u. k. Monarchy of up to 36,000 people who died on the gallows in the first months of the war. Tens of thousands of Ruthenians were deported to the Thalerhof internment camp .

On August 17, 1914, there was a massacre of residents in the small Serbian town of Šabac . 120 residents, mostly women, children and old men, who had previously been locked in the church, were shot and buried in the church garden by the troops on the orders of Field Marshal Lieutenant Kasimir von Lütgendorf . In the first days of the war there were mass executions in numerous other northern Serbian places. These took place according to plan and on higher orders.

There was also brisk partisan activity in the region . The execution of armed fighters who were not marked as combatants was common in all theaters of war at the time.

War year 1915

Mass desertion

This year, among other things, there were mysterious incidents about an alleged or actual mass desertion from infantry regiments No. 28 and No. 36. Both regiments were initially dishonorably disbanded because of these incidents and their flags were withdrawn. The exact circumstances have not yet been clarified. For example, eyewitnesses from the neighboring Landwehr Infantry Regiment No. 6 from Eger reported quite credibly that the majority of the Czech soldiers had defected to the Russians; this version is contradicted in the field files of the Austro-Hungarian army. Rather (according to the records of the Austro-Hungarian Military Justice) the units concerned were broken up in battle and the crew were almost completely captured. It is very likely that the matter was officially downplayed in order not to endanger the morale of the others or to encourage them to copy it. In the case of IR 28, after its dissolution, a marching battalion (No. XI) remained, which, due to Italy's entry into the war, was not assigned to its main unit, but was deployed on the southwest front, where it stood out in the first Isonzo battles. Because of these achievements, the command of the Southwest Front applied in August 1915 to set up IR 28 from this battalion again. The judgment of the field court of the 28th ITD, which ultimately exonerated the regiment, followed in December 1915. Thereupon the IR 28 from this XI. Marching battalion reorganized after its rehabilitation and again involved with the flag. The IR 36, however, was completely disbanded in May 1915 after the incidents and the remaining crew was divided up. The authorities quickly closed the case; even later there were no initiatives to restore the regiment or to rehabilitate it.

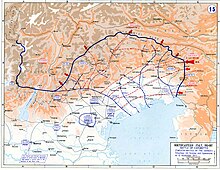

Battle of Gorlice-Tarnów

At the beginning of May 1915 an offensive by the allied German and Austrian troops began with the aim of breaking through the Russian front in the Gorlice area and relieving the Carpathian section. The 11th German Army and the 3rd and 4th Austro-Hungarian Army succeeded together on March 2nd and 3rd. May 1915 the breakthrough in the Battle of Gorlice-Tarnów ; it reached a depth of about 20 km after just one day. The Russian Carpathian Front was in full dissolution, the allies crossed the San at Jarosław and were able to recapture the Przemyśl fortress in June.

After the breakthrough of German troops between Gródek and Magierów on June 20, 1915, the Austro-Hungarian 2nd Army also recaptured Lemberg on June 22, 1915, largely restoring the condition of June 1914. Further attacks by the Central Powers in July 1915 led to the capture of Cholm , Warsaw and Brest-Litovsk .

Italy enters the war

When the First World War broke out, Italy had declared itself neutral; it interpreted the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary as a purely defense pact.

Italy conducted secret negotiations in London with states on the other side; Italy urged, among other things, to get Slavic areas on the Adriatic . After Russia agreed to this, the Secret Treaty of London came into being on April 26, 1915. On May 23, 1915 Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary.

As a result, the high command was faced with another theater of war for which no resources were available. Only five infantry troop divisions (No. 90-94) of the second category and 49 batteries of artillery with partly considerably outdated cannons could be mobilized. In addition, there were two squadrons of reserve cavalry, 39,000 standing riflemen and, as the backbone of the Italian front, the sometimes very outdated fortifications of the Austro-Hungarian border security. As reinforcement, Germany sent the Alpine Corps , an association with division strength , which, however, was not allowed to cross the Italian border, since Germany and Italy were not yet at war at that time. The Italian chief of staff, General Cadorna, hesitated because he was deceived about the forces actually facing him. The Standschützen had occupied all strategically important summits immediately and thereby suggested a troop strength that was never available. Cadorna repeatedly postponed the time of the attack because he was of the opinion that his units were not yet strong enough for a general attack on South Tyrol . Ultimately, he gave the Austrian commander-in-chief of the south-western front, Colonel General Archduke Eugen, the time he needed to bring reinforcements. Cadorna did not realize (or did not want to recognize) that he was at every point in time significantly superior to his opponent, both personally and materially. Intense fighting took place in South Tyrol only in front of the Austro-Hungarian fortress bar Lavarone / Folgaria , where the Italians made great artillery efforts to defeat the Verle , Lusern and Vezzena plants and also launched massive infantry attacks. The targets of these attacks were the Valsugana and the Lago di Caldonazzo . Here one could have bypassed the Trento fortress and penetrated north through the Adige Valley towards Bolzano . Why the Austrian front was overran at the strongest point is no longer understandable today. The mass deserts of Italian-speaking Austro-Hungarian soldiers hoped for by Italy and repeatedly propagated by Gabriele D'Annunzio did not materialize. The majority of the simple population of Trentino and the coastal region , the so-called irredenti - (the unsaved), who also had to provide the soldiers (around half of the Kaiserjäger consisted of Trientines), preferred to stay with Austria and not switch to Italy. This also influenced the fighting morale of these soldiers, which led to the fact that in 1916 a bon mot was circulating among the Italian infantrymen Dio ci liberi degli irredenti! (“God deliver us from the unsaved!”).

After Italy entered the war, the country became the new “main enemy” of the Austrian public. Italy was on the one hand an old opponent against whom the last successes on the battlefield had been achieved, and on the other hand an official ally within the Triple Alliance. Although there was never great confidence in Italy's loyalty, the majority of the Austrian population followed the outrage of Emperor Franz Joseph (“A breach of faith , the likes of which history does not know”). At the same time, entry strengthened public opinion in the “just cause” of war .

Suddenly the Slavic soldiers of the monarchy, who had previously had little motivation against Serbia and Russia, were also more ready to fight against the Italian aspirations for great power on the eastern Adriatic. The war against Italy produced a mood among the peoples of the monarchy that almost resembled that of Austria as a whole .

Isonzo

The second focus of the Italian attacks was the area in the southern Isonzo section and with it the period of the Isonzo battles , which did not proceed as hesitantly as in Tyrol . Carried by the wave of enthusiasm about the now finally imminent liberation of the unredeemed areas , Italy was optimistic that the city of Trieste would soon be brought home to Mother Italia (Gabriele d'Annunzio). The Italian 3rd Army was to break through between Monfalcone and Sagrado to the Doberdo high plateau, the 2nd Army between Monte Sabotino and Podgora. The minimum goal was to conquer the bridgehead at Gorizia , to cross the Isonzo, to conquer the mountains Kuk and Priznica (height 383, east of Plava), as well as an attack on the bridgehead at Tolmein . The strategic goal was the breakthrough to Trieste, then on to the Hungarian lowlands, where they wanted to unite with Russian troops and thus separate Austria from Hungary.

In a daily order from May 1915, General Cadorna had instructed his 2nd and 3rd Armies to advance into Austro-Hungarian territory with energetic and surprising actions immediately after the declaration of war. So began the First Isonzo Battle on June 23 . It lasted until July 7th and did not bring the desired success. By the end of the year General Cadorna was supposed to attack three more times ( Second Isonzo Battle - July 17 to August 10 / Third Isonzo Battle - October 18 to November 5 / Fourth Isonzo Battle - November 10 to December 11), but was able to attack again achieve only minor gains in terrain.

Personnel losses in the 1st – 4th Isonzo Battle (Fallen, Wounded, Missing, Prisoners)

| Austria-Hungary | Italy | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Battle of the Isonzo | 10,000 | 15,000 |

| 2. Battle of the Isonzo | 46,000 | 42,000 |

| 3. Battle of the Isonzo | 42,000 | 67,000 |

| 4. Battle of the Isonzo | 25,000 | 49,000 |

Second Serbian campaign

On September 6th, Bulgaria signed a military convention with the Central Powers and entered the war. The main reason for Bulgaria was the attempt to regain the Macedonian territories lost in the Second Balkan War , while Germany and Austria-Hungary promised themselves a land connection with the Ottoman Empire. It was also now possible to attack Serbia from three sides. For this purpose, an army group was set up under the command of the German General Field Marshal August von Mackensen . It included the Austro-Hungarian 3rd Army under General of the Infantry Hermann Kövess von Kövesshaza , the German 11th Army under General der Artillerie von Gallwitz and the Bulgarian 1st Army under Lieutenant General Bojadjieff. The attack began on October 5th and on October 7th, Austro-Hungarian troops landed on the northern edge of Belgrade. Two days later, after bitter street fighting, the city fell. An attempted intervention by the British and French troops standing near Saloniki was sealed off by the Bulgarian armed forces. The only thing left for the remnants of the Serbian army was to flee to the Albanian Adriatic coast, where they were picked up by Entente ships and brought to Corfu .

Fight in Palestine

Austria-Hungary had joined the German-Turkish secret treaties of August 2, 1914 and January 11, 1915 in the form of an exchange of notes. In terms of economic policy, the Ottoman Empire did not want to be inferior to its German ally. In order to strengthen the political influence in the Ottoman Empire, smaller military contingents were sent there (like the German Levant Corps ). These were artillery, technical troops and motorized transport columns.

War year 1916

With the conquest of Serbia at the end of 1915, the South Slav question became topical, as did the question of the relationship between subjugated Serbia and the monarchy. The Joint Council of Ministers met on January 7, 1916, under the impression of the expected military decision. Efforts were made to define the war aims of Austria-Hungary (→ war aims in the First World War ).

At the beginning of 1916, problems began to emerge that would lead to serious crises in the allied armies. The personal aversion that the two Chiefs of Staff von Falkenhayn and Conrad von Hötzendorf harbored for each other was (at least von Falkenhayn) also transferred to his field of work. This ranged from a lack of cooperation to the non-involvement of the Austro-Hungarian troops in the strategically uniform orientation of operations.

The German units were run completely independently, whereby the Austrian troops were only seen as appendages in some places, even if without them one would not be capable of major operations in the northeast and in the Balkans.

Difficulties arose from the different objectives for the year 1916. The Austro-Hungarian leadership thought it sensible to focus on a victory against Italy and to liquidate this front (which would have had an impact on the entire course of the war); on the other hand, the German General Staff preferred to concentrate on the Battle of Verdun .

Campaign against Montenegro

Regardless of this, Conrad von Hötzendorf continued to pursue his own strategy. This included first establishing facts in the Balkans and wrestling Montenegro down. He wanted to push in the Italian bridgeheads at Durazzo and Valona and drive the French Orient Army out of Saloniki. For this purpose, the 3rd Army, reinforced by the troops of the Commanding General from Bosnia , Herzegovina and Dalmatia, was deployed to Montenegro in January . Thereupon the small Montenegrin army withdrew fighting on the fortified massif of Lovćen . On January 8th, massive attacks on the mountain began, with the Austrian troops being supported by the naval artillery of the Austro-Hungarian Navy . On 10/11 On January 1st, the Lovćen was largely conquered, the remnants of the Montenegrin armed forces capitulated on January 17th. The offensive was initially continued in the direction of Albania and the Italian army was forced to evacuate Durazzo . Since not enough troops were available, the possible occupation of all of Albania could not be carried out. As a result, there was a large gap in the front between the Austro-Hungarian units in Albania and the German-Bulgarian troops in Macedonia, which had to remain open.

Spring offensive against Italy

Since the Austro-Hungarian General Staff insisted on carrying out a massive blow against Italy, the offensive began on May 15, postponed several times due to bad weather, across the plateau of the seven municipalities in the Lavarone / Folgaria area towards Padua and Venice . A planned pincer movement from the Isonzo front, with which the Italian region of Veneto should be cut off, could not take place because Germany did not want to provide the necessary support.

The 11th Army (Colonel General Dankl) and the 3rd Army (Colonel General von Kövess) commissioned with the downsized offensive were initially successful; Among other things, the plateau with the Italian forts Monte Verena and Campolongo and fortifications in the Val d'Astico ( Forte Casa Ratti ) were conquered. Then the offensive got stuck. On the one hand, this was due to the fact that the Italians, after realizing that there was no danger from the Isonzo, withdrew more and more troops from there and positioned them in dangerous places. On the other hand, the Austrians were forced to withdraw troops for the Brusilov offensive , which began on June 4, and to move them to the northeast front in Volhynia . The offensive on the South Tyrol front therefore had to be stopped. They withdrew to a straightened front line and went back into position warfare.

The Brusilov Offensive

The Brusilov offensive was a disaster for the Austro-Hungarian armed forces. The attack had been planned with four armies and strong artillery forces only for the Russian western front, whereby the units on the south-western front under General Brusilov should only intervene in support. In the area of the 4th Austro-Hungarian Army, the well-developed positions at Luck were simply overrun and a breakthrough of 85 kilometers wide was achieved, which by June 10 had reached a depth of 48 kilometers. Also on June 10, the Russian forces managed to tear open the front in the area of the 7th Austrian Army near Okna. A relief attack launched in Volhynia with reserves that had been brought about did not have the desired effect and Luck could not be recaptured. On June 17th the Russian forces succeeded in conquering Chernivtsi , with which the entire Bukovina was lost. In July the Central Powers were able to stabilize the northeast front more or less. The result was personnel losses totaling 475,000 men (including 226,000 prisoners).

The 5th – 9th Isonzo battle

Knowing that Germany would not intervene to provide support, the Italian leadership demonstratively began the Fifth Isonzo Battle on March 11th . It was directed against Monte San Michele and Monte San Martino and was only of local character. It had no effect on the course of the front. Another attack on August 4th led to the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo , which lasted until August 15th and in the course of which the Italians managed to conquer the city of Gorizia, Monte San Michele and the Doberdo plateau. The Seventh Isonzo Battle took place from September 13th to 17th, the Eighth Isonzo Battle from October 9th to 12th and the Ninth Isonzo Battle from October 31st to November 4th, all of which achieved certain land gains, but a breakthrough to Trieste was still possible before cannot be reached. In the course of these battles Austria-Hungary suffered losses of around 100,000 men, losses which were very difficult to replace and which caused great problems because of further attacks that were to be expected.

Personnel losses in the 5th – 9th Isonzo Battle (Fallen, Wounded, Missing, Prisoners)

| Austria-Hungary | Italy | |

|---|---|---|

| 5th Battle of the Isonzo | 2,000 | 2,000 |

| 6. Battle of the Isonzo | 42,000 | 51,000 |

| 7. Battle of the Isonzo | 15,000 | 17,000 |

| 8. Battle of the Isonzo | 20,000 | 25,000 |

| 9. Battle of the Isonzo | 28,000 | 35,000 |

Campaign against Romania

After the disastrous course of the summer for Austria-Hungary, Romania no longer resisted the Allied recruitment and entered the war on August 27 on the side of the Entente (→ Romania's war aims ). The Central Powers did not consider the Romanian army to be a threatening enemy because of its personnel and material resources; nevertheless, the country's strategic location would make it imperative to eliminate it. On the part of the Vierbund, however, no units were available for an immediate reaction after the Brusilov offensive. It was therefore decided to wait for the time being and only become active after the reorganization of one's own strengths. Taking advantage of this weakness, the Romanians marched on the day war was declared in the the Kingdom of Hungary belonging Transylvania , which present here only to a limited extent Border Guards driving before it. This made a reaction of the allies imperative, who mobilized all the troops still available and the 9th (German) Army under General der Infantry von Falkenhayn and the 1st (Austro-Hungarian) Army under General der Infanterie Arz von Straussburg to recapture Put Transylvania on.

At the same time, the Bulgarians attacked in Dobruja and inflicted some heavy defeats on the Romanians. Although the Russians launched a relief offensive and the Entente troops attacked from Salonika, they were unable to prevent the defeat of Romania's armed forces. After the occupation of Wallachia , Bucharest was also taken on December 6th . The remaining Romanian troops initially fought on the Russian front. This military adventure cost Romania almost 500,000 dead, plus a large number of wounded and prisoners of war.

Emperor Karl I.

On November 21, the commander-in-chief, Emperor Franz Joseph I, died after 68 years in government at the age of 87. He was followed by his great-nephew Carl Franz Joseph, who, as Emperor Karl I of Austria and King Karl IV of Hungary, took over the supreme command of the entire armed power by daily order of December 2, 1916. The previous army commander, Field Marshal Archduke Friedrich , remained the monarch's deputy in this function until February 11, 1917 and was then replaced by Karl I./IV. to the "highest disposition" (and thus actually in the reserve). Chief of Staff Conrad was replaced by the monarch on March 1, 1917 by Arthur Arz von Straussenburg . On November 3, 1918, Karl I./IV. the high command to Arz and ordered FM on November 4th at his request. Kövess to the (last) army commander. On November 6, 1918, the monarch issued the demobilization order.

In contrast to his predecessor, who had never left Vienna to visit the front, the new Commander-in-Chief traveled from one section of the front to another, investigated the situation and inspected the troops on the spot.

care

The general supply situation began to deteriorate noticeably from this year onwards, although the domestic supply industry was able to show increasing production figures. From April 1, 1915 to March 31, 1916, the following quantities were made available to the army:

- 2,622,900 / piece blouses

- 2,976,690 / piece of pants

- 1,328,090 / piece coats

- 3,948,060 / pair of shoes, boots, half-boots

- 6.237.700 / laundry sets

- 134.220 / piece cartridge pouches

- 446,848 / piece backpacks

- 665,400 / each tent sheets

- 125,250 / piece spade

However, quantity was given priority over quality, which then significantly reduced the "standard wearing time": pieces of clothing had to be repaired or replaced with new ones as soon as possible.

A continuous supply of the troops only took place after the front lines had solidified, when the army bodies began to independently set up clothing depots and create reserves. This resulted in a very different clothing level. While one division was even able to hand out special work clothes, others did not even have the basic equipment required.

War year 1917

The year 1917 began with structural changes in the army. In February the previous Chief of Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf was replaced and (similar to his German counterpart Falkenhayn) reinstated as a troop leader. He was given command of an army group on the south-western front. He was succeeded by General of the Infantry Arz von Straussburg . Before his replacement, Conrad had determined the direction of march for 1917, in which a liberation attack against the Italians on the Isonzo was called for in order to avert the threat to Trieste and Ljubljana . A significant change in the external appearance was the introduction of the steel helmet . After the troops deployed on the Isonzo had increasingly demanded effective head protection due to the eminent danger posed by stone fragments, the machinery slowly started up. Since a corresponding production line was not available, steel helmets were initially ordered in Germany and 124,000 pieces were delivered until the in-house production began in May 1917. The deliveries from Germany - a total of 416,000 pieces - lasted until January 1918.

Change of concept of infantry

Meanwhile the nature of the war had fundamentally changed. The infantry attacks in the style of 1914 were no longer possible with the expanded position systems and artillery massing. The German army had recognized this problem and in 1915/16 began to train the first units on the western front with the tactics of shock troops and storm troops. The Austro-Hungarian army also adopted this tactic and set up assault battalions, initially at army level, and later also at troop division level.

Situation in Russia

In Russia, the situation had changed dramatically due to the deteriorating supply situation. Unrest among the people in the hinterland should be put down by the army. The refusal of various regiments to shoot defenseless civilians led to the mutiny in St. Petersburg on March 12 , the outbreak of the Russian Revolution and the abdication of the Tsar. The effects on the troops at the front were disastrous: signs of disintegration became more and more evident, and entire units ran over to the German or Austro-Hungarian lines. The revolutionary government under Kerensky still tried to fulfill its alliance obligation towards the Entente and on June 29 launched the so-called Kerensky offensive against the Central Powers.

With the available troops and material (partly already from British aid deliveries) an attempt was made to break through to Lemberg against the Austro-Hungarian 2nd and 3rd Armies. This also under the aspect of neutralizing the domestic political difficulties. In Zborow was the Russian side one of deserters Infantry Brigade formed and Czech prisoners of war used to here on two Bohemian infantry regiments met the little institutions made on their compatriots to shoot. It was here that signs of dwindling loyalty to the empire began to emerge.

The Russian offensive collapsed at the 3rd reserve position of the Austrians, whereby in retrospect Kerensky, who had taken over the leadership himself, was certified to be highly dilettantism, which was one of the reasons for the failure. On July 19, the counter-offensive began, which the demoralized Russian troops could no longer counter. Eastern Galicia and Bukovina had been recaptured by mid-August, and the imperial border had been reached again. The fighting turned into a trench warfare again.

The 10th and 11th battles of the Isonzo

On the south-western front, it took until mid-May to get the Italian army ready to fight and attack again. General Cadorna began the Tenth Battle of Isonzo on May 12th, which lasted until June 5th. After two and a half days of barrage on the entire front section from Tolmein to the Adriatic Sea , a previously unknown intensity , the main attack took place south of Gorizia, again with the aim of breaking through to Trieste. Although the Austro-Hungarian troops put up tough resistance, the Italians managed to break in numerous times and the commander of the 5th Army, Colonel General Boroevic, had to bring in reserves early on. On May 23, Cadorna struck a second heavy blow, so that the Austro-Hungarian leadership felt compelled to withdraw troops for reinforcement from the northeast front. Furthermore, associations from Tyrol and Carinthia were brought in. In counter-attacks, the Austro-Hungarian forces succeeded in recapturing the so-called Flondarstellung on June 4th. The Italian land gains were limited to the summit of the Kuk height, the formation of a bridgehead on the left bank of the Isonzo and its assertion.

On August 17, Cadorna again attacked the depleted units of the Austrian 5th Army in the Eleventh Isonzo Battle . With his strongest troop massing to date, he managed to cross the Isonzo in several places and conquer the high plateau Bainsizza. Simultaneous attacks by the Italian 3rd Army on the Hermada hill failed despite the gain in terrain. As is so often the case, the Italian commanders hesitated to make full use of the partial successes they had achieved. The Austrian Commander in Chief Boroević was therefore able to gather his troops in the second line of defense and be buried. The new front line ran in the territory of the Italian 2nd Army after the battle on the line: Monte Santo (Kote 682) - Vodice (Kote 652) - Kobilek (Kote 627) - Jelenik (Kote 788) - Levpa. In the section of the 3rd Italian Army, it ran on the line: Log - Hoje - Zagorje - San Gabriele.

The 12th Isonzo Battle

At the Austro-Hungarian headquarters in Baden near Vienna , it was recognized that another attack of this kind could no longer be repelled by their own troops. In order not to be overrun, you had to take the initiative yourself. After consultation with the German ally, who provided seven divisions, numerous artillery, mine and gas cannon units as the 14th Army under General der Infantry von Below , the previous 1st and 2nd Isonzo Armies were merged to form Army Group Boroevic to attack the combat action known as the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo against the Italian Isonzo Front.

In the twelfth battle of the Isonzo (also Battle of Karfreit , Italian Battaglia di Caporetto ), the Italian troops suddenly found themselves in the unfamiliar role of the attacked. Although the time of the attack had been revealed by defected Czech and Ruthenian officers, the Italians again hesitated to order suitable countermeasures. On October 24th, the allied troops began to prepare for artillery, which consisted of unusually large amounts of gas fire . As a result, deep break-ins had already been made in the Flitsch and Tolmein area that morning and countless prisoners were taken. Despite the numerical superiority of the Italian troops, the front trenches, which were far too densely occupied, and the incorrect use of reserves enabled the operational breakthrough.

On October 27th, the Italian 2nd Army collapsed completely. On October 28th, Udine , the headquarters of General Cadorna, who had fled with his staff a few hours earlier , was captured. The Italian 3rd Army also had to withdraw, otherwise they ran the risk of being surrounded. Gorizia fell to the Austro-Hungarian troops without resistance.

By then, the Italian army had lost around 200,000 prisoners and a significant amount of military equipment. Surprised by this success itself, the command of the south-western front ordered the pursuit initially as far as the Tagliamento , which could be crossed on October 31 without any problems.

As a further effect on the Italian troops on the front of the Carnic Alps and the Dolomites , which were suddenly hanging in the air here, the 4th Army (General Giardino ) had to give up all conquered and claimed positions as quickly as possible and thus leave them to the Austrians.

The imperial and royal 10th Army, under Feldzeugmeister von Krobatin and 11th Army under Colonel General Conrad von Hötzendorf, broke through the Italian locking bars at Pieve di Cadore , Belluno and in Valsugana; but they did not get beyond the Asiago - Monte Grappa line . On November 1st, the Piave was crossed and bridgeheads were set up on the western bank. The Italian government was already considering relocation to the south of the country, as a military vacuum had opened up west of the Piave. On the Piave, however, the advance came to a standstill. The reasons for this are unclear; it was probably due to the exhaustion of the troops, the overstretched supply routes and / or the poor supply situation in general. Although the Italian army was completely demoralized and exhausted, Austria-Hungary could not win the war here as the Allies immediately began moving troops to northern Italy to cushion the shock. On November 10, the western bridgeheads on the Piave had to be abandoned. With the help of the USA , the existence-threatening Italian material losses could be quickly compensated for. The army was rebuilt under the corset of the French support divisions.

| Total losses | Austria-Hungary | Italy |

|---|---|---|

| 10th Battle of the Isonzo | 40,000 | 63,000 |

| 11. Battle of the Isonzo | 100,000 | 150,000 |

| 12th Isonzo Battle | 5,000 | > 300,000 |

War year 1918

At the beginning of the year 4,410,000 men were still in service, 2,850,000 of them at the front and 1,560,000 with the task forces, military authorities, commandos and institutions at home.

care

Even the mass of material captured in the Twelfth Isonzo Battle could not hide the increasingly difficult supply situation. The land bled more and more; many resources were running out. Military supplies had priority; the armaments industry demanded top performance (see also war economy ); the civil sector fell short. Due to the Allied trade blockade (see also naval blockades in World War I , naval warfare in World War I ), the troops received more and more inferior material (also known as "junk" (= junk)), which was not conducive to fighting strength and morale .

Salonikifront

Since the Americans were not yet able to use the forces available to them to the full extent, the Central Powers still represented a military force that should not be underestimated in the spring of 1918. However, the German Supreme Army Command now began troops from all fronts for the planned breakthrough battle in France to contract. This primarily affected the Macedonia Front, where the already weakened Bulgarian troops could only withstand the attacks of the Orient Army of the Entente until September. Then came the military collapse and the surrender of Bulgaria.

Piavefront

On the Piavefront, the situation has not improved noticeably, despite the shortening of the front and the associated troop reinforcements. The Italians had compensated for the personnel and material losses from the 12th Isonzo battle and with the new Chief of Staff General Armando Diaz , who had replaced the hapless General Cadorna after the Isonzo disaster, a breath of fresh air was blowing through the Italian army.

The German Army Command now demanded that the current Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff, Colonel General Arz von Straussenburg, bind Allied troops to prevent them from being transferred to the Western Front. Since Arz von Straussenburg was significantly more friendly towards the Germans than his predecessor, this request was immediately considered benevolently and a limited offensive in the Monte Grappa area with a push to the Brenta was planned. The commandant of Army Group Tyrol, Conrad von Hötzendorf, was of the opinion, however, that one should attack further north between Piave and Astico . Colonel-General von Boroevic, on the other hand, saw the greatest opportunities for success on the southern Piave. Arz von Straussberg could not assert himself against his two troop leaders and ordered a compromise such that Boroevic should attack in a pincer movement towards Venice, destroy the 3rd Italian Army of General Duke of Aosta and then swing north towards Padua. Conrad von Hötzendorf was to attack south with the 11th Army, eliminate the 1st Italian Army of General Brusati and also advance to Padua via Vicenza . That would have closed the tongs and encircled the 4th Italian Army. The 2nd Italian Army (General Capello) gathered around Padua and the Allied Army of Marshal Foch gathered around Mantua were not considered .

The Austro-Hungarian troops were no longer sufficient for such an effort. The offensive, postponed from May 20 to June 15, suffered such high losses east of the Brenta on the Asiago plateau on the first day that the attacks had to be stopped again on June 16. On the lower Piave, Boroevic's army forced the passage across the river in several places. However, since the war bridges could not be kept in the necessary operational condition due to the strong flood and also the bombardment by the Italian artillery, the bridgeheads were abandoned and the offensive was broken off on June 20th.

The personnel losses of almost 150,000 men that occurred during the two attack operations could no longer be replaced. Even the lost military equipment could not be easily obtained again. The first signs of decomposition became noticeable. In particular, the former prisoners of war returning from Russia after the Brest-Litovsk peace treaty of March 3 were unwilling and in some cases brought with them Bolshevik ideas. Nevertheless, all further Italian attacks were completely repulsed. It was to be foreseen, however, that the Austro-Hungarian front would collapse under the man and material superiority of the Allies.

The Tonale Pass offensive , launched on June 13 and intended as a relief attack, was also doomed to failure and collapsed almost instantly.

Battle of Vittorio Veneto

The last battle fought from October 24, 1918 to November 3 or 4, 1918, was the Battle of Vittorio Veneto or the Third Battle of the Piave. The main theaters of war were the Piave river and the Grappa massif . With 7,750 guns and 650 aircraft, Italy went into battle better equipped than Austria-Hungary (6,800 artillery pieces and 450 aircraft). With the support of the Entente powers and Czech deserters, the well-cared for, rested and excellently armed Italian units were able to launch a successful offensive against the emaciated and completely demoralized Austro-Hungarian troops, who lacked everything. There was nothing more to oppose to the Allied superiority. By November 1, the Italians and their allies had reached a line roughly Asiago - Feltre - Belluno in the west , and crossed the Livenza river , parallel to the Piave, in the east . Until November 4th, large parts of Friuli and Trentino were in Italian hands. On the Italian side, 5,800 deaths and 26,000 injuries were recorded. On the Austro-Hungarian side, 35,000 dead, 100,000 injured and 300,000 prisoners were counted.

With the Battle of the Piave “Italy achieved an incomparable and grandiose victory” ( Benito Mussolini ). To celebrate the victory, Ermete Giovanni Gaeta composed the Piavelied (La Canzone del Piave) , which in the years 1946–1948 even served as the national anthem of the young Italian republic.

Others were more critical of the extent of this Italian victory. The publicist Giuseppe Prezzolini , who witnessed the battle as an eyewitness, was of the opinion: “Vittorio Veneto was not a military victory, for the simple reason that there has to be a battle in order to achieve a victory and so that there is a battle , there must be an enemy fighting. But now there was an enemy in Vittorio Veneto who withdrew. Vittorio Veneto was a retreat that we threw into disorder and confusion; not a battle that we won. "

| Associations involved in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto | |

|---|---|

| Italy | 51 divisions |

| France | 2 divisions |

| Great Britain | 3 divisions |

| Czechs | 1 division |

| United States | 1st infantry regiment |

| Austria-Hungary | 18 divisions 1st category 14 divisions 2nd category |

The end

Dissolution phenomena

As early as October 22, there were massive refusals of orders by Hungarian and Croatian units, which were soon joined by the Czechs and Bosniaks. The dual monarchy Austria-Hungary was in the process of dissolution. Neither the government in Vienna nor that in Budapest had any authority or authority in those parts of the country whose people wanted to found their own state. Proclamations by the representations of the Croatians , Serbs and Slovenes on October 6th, the Poles on October 7th and the Czechs (who already had a Czechoslovak government in Paris ) on October 28th had meant that many soldiers of these nationalities made no sense saw another fight and wanted to return home as soon as possible. The Hungarian government, which declared the real union with Austria in mid-October by a resolution of the Reichstag on October 31, 1918 (with the consent of the monarch), officially demanded that the Army High Command officially repatriated the Hungarian regiments from the Italian front immediately and completely.

The first units put this into practice immediately and left their combat sections to make their way home. The resulting gaps in the front had to be filled in by the associations that were still standing. A not inconsiderable number of Czechs defected to the Italians and were immediately equipped by them and reorganized in combat units, as the new Czechoslovakia had already achieved the status of an ally of the Entente through the work of its politicians in exile. A complete division of deserted Czech soldiers was on the side of the Allies in 1918 on the Piavefront; they were equipped with Italian uniforms in the style of the Alpini.

Despite the extensive enemy areas that the Austro-Hungarian army still occupied in the east, the Balkans and northern Italy at the beginning of November 1918, the catastrophic supply situation for troops and civilians, which had been virulent for a long time, was overcome by the enemy with the support of the Czech government-in-exile or the Italian Irredenta promoted separatist aspirations (self-determination without Habsburg) and the dramatic increase in strength of the opponents through the entry of the war in the United States in 1917 cannot be outweighed. The cessation of fighting by the Austro-Hungarian Army would not have been postponed much longer, even without the armistice.

Overall situation at armistice

In the classical, military sense, the Austro-Hungarian army had remained undefeated until then (the relevant requirements were not met - it had not surrendered, there was no crushing defeat and the country was not occupied by the enemy), but this was only possible at the time of Ceasefire and cannot hide the fact that resistance beyond autumn / winter 1918 would not have been possible.

At the beginning of the armistice negotiations at the end of October 1918, the following situation arose for the Austro-Hungarian army:

With the use of all last available forces, it was possible to hold the front lines until the armistice negotiations, but this did not change the outcome. Contrary to the expectations of its own high command, it was even possible to repel the first attacks of the Allied major offensive on October 24, 1918 on the south-western front, even if this was ultimately no longer of great importance. Although individual troops still offered considerable resistance, such as the kuk XXIV Corps under General Hafdy, it came through further mutinies (e.g. the Budapest Jäger Battalion 24, the Czech rifle regiment "Hohenmauth" No. 30 and others) and the abandonment of the Front line through entire divisions (27th and 38th Infantry Troop Divisions) meant that the front had to be withdrawn further and further or the combat troops were pushed back and the situation became increasingly untenable.

In detail, however, the Austro-Hungarian troops and their allies were still occupied when the armistice negotiations began at the end of October 1918:

- Almost all of today's Poland, part of Belarus and the Ukraine with an area of around 700,000 km² and around 40 million inhabitants.

- The then Kingdom of Romania with an area of 130,000 km² and around 10 million inhabitants.

- Serbia, Montenegro and Albania with an area of 150,000 km² and 7 million inhabitants.

- The Friuli and parts of Veneto with an area of 15,000 km² and about 2 million inhabitants.

armistice

After the battle of Vittorio Veneto, General Viktor Weber headed Edler von Webenau on behalf of the AOK. the Austro-Hungarian Armistice Commission, which was supposed to negotiate the armistice with the Italians. The commission, which had already been formed at the beginning of October, moved to its headquarters in Trento on October 28, 1918 . On the morning of October 29th, Captain Camillo Ruggera , accompanied by a non-commissioned officer with a white flag , approached the Italian lines near Serravalle south of Rovereto to deliver a note to the Italians asking for the ceasefire negotiations.

The following armistice at Villa Giusti near Padua , which was signed on November 3, 1918 and was to come into force on November 4, was no longer the subject of negotiations due to the partial breakdown of the Austro-Hungarian resistance, but was named the Entente dictated by the head of the Italian delegation, Pietro Badoglio . Among other things, the representatives of Austria and Hungary were forced to agree to the evacuation of Tyrol as far as the Brenner and Reschenscheidecklinie, to deliver the entire war fleet (which, however, had already been left to the new South Slavic state at the end of October because German Austria had no access to the sea) and to the to give allied troops freedom of movement in the defeated country. The rejection of the submission dictate would have had far worse consequences than the acceptance.

Due to the weak decision-making of Emperor Karl I (who absolutely wanted to involve the German-Austrian Council of State in the decision, but after a long wait only obtained knowledge of the incident without comment), uncertainties arose in the chain of command as to whether the armistice had already been concluded and when it would go into effect. (Troops that had long since been unwilling to fight might also be of the opinion that the treaty would take effect immediately upon conclusion.) In any case, the Austrian troops were sometimes allowed to lay down their arms up to 36 hours before the official date, which led to the Italians surprising around 350,000 Austrian -Hungarian soldiers could be captured without resistance. The catastrophic conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps cost many lives; the Italian army was not prepared for this mass of prisoners and failed to provide for them in accordance with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations .

An armistice and a later peace agreement came about between a rest of Austria, almost incapable of acting as a state, and an alliance that had become overpowering (with Italy at the top, which had been maneuvered into this war out of calculation ( London Treaty ) and now rigorously demanded its promised territorial gains; Tyrol became until immediately occupied). Italian troops advanced as far as Innsbruck , from where they did not withdraw until the end of 1920, and sent a military mission to Vienna to requisition works of art.

Only the Isonzo army and parts of the high mountain troops were able to withdraw successfully and thereby largely escape capture.

The retreat of the defeated took place partly in organized groups, partly individually. Units that had reached German-Austrian territory in good order mostly disbanded here because many German-Austrian soldiers simply left the return trains as soon as they believed they could make the further journey home to their place of residence more quickly. Hungarian and Czech units transferred through German Austria behaved differently; they knew that they were expected at home as soldiers. On the way home, the Czechs in particular felt that they belonged to the winners and let the German-Austrians feel it, among other things in a shootout with German-Austrian troops at Vienna's Westbahnhof. At home these troops were immediately used to set up their own national units and in some cases, as in the border area between Carinthia and Slovenia, immediately deployed against German-Austria to secure territorial claims.

losses

Out of a total of about 8,000,000 men, 1,016,200 soldiers died or died (including about 30,000 men who fell victim to avalanches or other adverse weather conditions in the high mountains), 1,943,000 men were wounded. 1,691,000 were captured, of which 480,000 died mostly of malnutrition and disease. The percentage losses were 13.5% for the officers' corps and 9.8% for the men and women. An estimated 30,000 former soldiers died as civilians after 1918 from wounds or hardship suffered during the war.

Museum reception

The history of the Austro-Hungarian Army in World War I is presented in detail in the Vienna Army History Museum (Hall VI) . Uniforms, armament and equipment of all powers participating in the war, such as the Austrian infantry and the cavalry; then u. a. German Empire , Russian Empire and Kingdom of Italy . The mountain war of 1915–1918 also played a major role . A special piece here is the 7 cm M 1899 mountain cannon, which formed the highest gun emplacement in Europe in the Ortler summit zone at 3850 meters. On the right-hand side of the room there is a larger selection of paintings by war painters who served in the Imperial and Royal War Press Headquarters during the war and captured their impressions in pictures . Another room shows heavy artillery pieces, e.g. B. an Austrian howitzer M 1916 with a caliber of 38 cm, which could fire projectiles with a weight of 700 kg over 15 km.

The Albatros B.II training and reconnaissance aircraft on display was one of the 5,200 aircraft used by the Army and the Austro-Hungarian Navy in World War I (see also Austro-Hungarian Aviation Troops ). A long showcase shows innovations in weapon technology and equipment from 1916, e.g. B. the first Austrian steel helmet that was made according to the German model. Other artillery pieces of various calibers are also set up.

literature

- M. Christian Ortner : The Austro-Hungarian Artillery from 1867 to 1918. Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-902526-12-0 .

- Austrian Federal Ministry for the Army and War Archives. Under the direction of Edmund Glaise-Horstenau (Ed.): Austria-Hungary's Last War 1914–1918. Volume I-VII. Verlag der Militärwissenschaftlichen Mitteilungen, Vienna 1930–1939. ( Digitized version ).

- Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck , Erich Lessing : The K. (below) K. Army. 1848-1914. Bertelsmann, Munich et al. 1974, ISBN 3-570-07287-8 .

- BMLVS (ed.): The First World War in Europe 1914/15. Troop service special No. 22, Vienna 2014.

- Exercise regulations for the kuk infantry. Vienna 1911.

- Anton Holzer : The other front. Photography and propaganda in the First World War. 3. Edition. Primus, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-86312-032-0 .

- Anton Holzer: The executioner's smile. The unknown war against the civilian population 1914–1918. With numerous previously unpublished photographs. 2nd Edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2014, ISBN 978-3-86312-063-4 .

- Heinz von Lichem: The lonely war. First complete documentation of the mountain war 1915–1918 from the Julian Alps to the Stilfser Joch. 2nd Edition. Athesia Verlag, Bozen 1981, ISBN 88-7014-174-8 .

- Hannes Leidinger , Verena Moritz , Karin Moser, Wolfram Dornik: Habsburg's dirty war. Investigations into the Austro-Hungarian warfare 1914–1918. Residence, St. Pölten 2014, ISBN 978-3-7017-3200-5 .

- Heinz von Lichem : The Tyrolean High Mountain War 1915–1918 in the air. The old Austrian Air Force. Steiger Verlag, Innsbruck 1989, ISBN 3-85423-052-4 .

- Heinz von Lichem: With a play tap and edelweiss. Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 1977, ISBN 3-7020-0260-X .

- Hans Magenschab : The grandfathers' war 1914–1918. The forgotten of a great army. Verlag der Österreichische Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-7046-0115-2 .

- Mario Christian Ortner , Hermann Hinterstoisser: The Austro-Hungarian Army in the First World War. Uniforms and equipment. 2 volumes, Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-902526-63-2 .

- M. Christian Ortner: The Austro-Hungarian Army and its last war. Verlag Carl Gerold's Sohn, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-900812-93-5 .

- Manfried Rauchsteiner : The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz et al. 1993, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 .

- Manfried Rauchsteiner: The First World War and the end of the Habsburg Monarchy. Böhlau, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-205-78283-4 ( completely revised and significantly expanded version of the work published in 1993).

- Stefan Rest, M. Christian Ortner, Thomas Ilming: The emperor's rock in the First World War. Uniforms and equipment of the Austro-Hungarian Army from 1914 to 1918. Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-9501642-0-0 .

- Walther Schaumann : From the Ortler to the Adriatic Sea, the Southwest Front 1915–1918 in pictures. Verlag Mayer, Vienna 1993, ISBN 3-901025-20-0 .

- Viktor Schemfil: The fights on Monte Piano and in the Cristallo area (South Tyrolean Dolomites) 1915–1917. Written on the basis of Austrian war records, descriptions of fellow combatants and Italian war history works ( Schlern writings , 273). 2nd Edition. University Press Innsbruck, Innsbruck 1984, ISBN 3-7030-0145-3 .

- Viktor Schemfil: The Pasubio Fights 1916–1918. Exact history of the struggle for one of the most important pillars of the Tyrolean defense front. Written on the basis of Austrian field records and Italian war history works. Book Service South Tyrol, Nuremberg 1984, ISBN 3-923995-03-2 .

- Robert Striffler: The Mine War in Ladinia. Col di Lana, 1915–1916 ( series on contemporary history of Tyrol 10). Book Service South Tyrol, Nuremberg 1996, ISBN 3-923995-11-3 .

- Michael Wachtler , Gunter Obwegs: Dolomites. War in the mountains. 3. Edition. Athesia Verlag, Bozen 2003, ISBN 88-87272-42-5 .

- Fritz Weber : The end of the army. Steyrermühl publishing house, Leipzig / Vienna / Berlin 1933.

- Michael Forcher : Tyrol and the First World War . Haymon, Innsbruck 2014, ISBN 978-3-85218-902-4 .

- Thomas Edelmann: In the back of the fighting troops , 2017, online in the HGM knowledge blog .

- Italian-language literature

- L'esercito italiano nella grande guerra (1915-1918). Volume I-III. Ministero della Guerra - Ufficio Storico, Roma 1929–1974.

- Gian Luigi Gatti: Dopo Caporetto - Gli ufficiali P nella Grande guerra: propaganda, assistenza, vigilanza. Libreria Editrice Goriziana [Leguerre], 2000.

- Mario Silvestri: Riflessioni sulla Grande Guerra. Editori Laterza [Quadrante], 1991.

- Luciano Tosi: La propaganda italiana all'estero nella prima guerra mondiale - Rivendicazioni territoriali e politica delle nazionalità. Del Bianco Editore [Civiltà del Risorgimento], 1977.

- Paul Fussel: La Grande Guerra e la memoria moderna. Società Editrice il Mulino [Biblioteca Storica], 1975.

- Elisa Fabbi: La propaganda italiana durante la prima guerra mondiale. Liceo classico statale (Dante Alighieri) Gorizia 2004.

- Sergio Tazzer: Piave e dintorni. 1917-1918. Fanti, Jäger, Alpini, Honvéd e altri poveracci. Kellermann Editore. Vittorio Veneto , 2011.

- Sergio Tazzer: Ragazzi del Novantanove. "Sono appena nati ieri, ieri appena e son guerrieri". Kellermann Editore, Vittorio Veneto, 2012.

Web links

References and footnotes

- ↑ An example of this setting is the ordinance of 1915, according to which all regimental names of honor and additional designations are to be omitted in the future and the associations are only allowed to be designated with their master number - however, “all existing stamps and forms must be used first [sic! ] ".

- ↑ Ortner p. 382.

- ↑ Günther Kronenbitter: "War in Peace". The leadership of the Austro-Hungarian army and the great power politics of Austria-Hungary 1906–1914 . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56700-4 , p. 22.

- ↑ even if there were no pioneers and no train here.

- ^ Glaise-Horstenau: Austria-Hungary's last war , vol. I, p. 28 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Joly: Standschützen. Schlern-Schriften, Innsbruck 1998, p. 269.

- ↑ Wolfgang Joly: Standschützen. Schlern-Schriften, Innsbruck 1998, p. 493.

- ↑ Exercise regulations

- ↑ Alistair Horne: The reward of fame. Bastei, Lübbe 1980, p. 25.

- ^ Archduke Friedrich in a letter of congratulations on the emperor's 84th birthday on August 18, 1914, in: official daily Wiener Zeitung , No. 197 of August 21, 1914, p. 1.

- ↑ Austrian Federal Ministry for Army Affairs, War Archives (ed.): Austria-Hungary's Last War 1914-1918 , Volume I: The War Year 1914. From the outbreak of the war to the outcome of the battle at Limanowa-Lapanow , Verlag der Militärwissenschaftlichen Mitteilungen, Vienna 1930, p. 80, online at digi.landesbibliothek.at

- ↑ Stefan Rest, Christian M. Ortner , Thomas Illmig: The Emperor's Rock in World War I. Uniforms and equipment of the Austro-Hungarian Army from 1914 to 1918. A publication by the Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien, Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-9501642-0-0 , p. 8.

- ^ Anton Graf Bossi-Fedrigotti: Kaiserjäger , Stocker Verlag , Graz 1977, p. 40.

- ↑ Max von Hoen: Jaroslawice 1914. Amalthea Verlag, Vienna 1929, p. 95 ff.

- ↑ The Smile of the Executioners: The Unknown War Against the Civilian Population ( Memento from December 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) (ORF)

- ↑ a b Anton Holzer: The executioner's smile (Spiegel-Online)

- ^ Max Hastings: Catastrophe 1914. Europe Goes to War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013, ISBN 978-0-385-35122-5 , p. 226.

- ↑ Herbert Lackner : Literally hacked up. In: Profile 44 (2014) from October 27, 2014.

- ^ Anton Holzer: By all means. In: Die Presse from September 19, 2008.

- ↑ On the Russian side, a Czech legion was formed from the same deserters or Austro-Hungarian soldiers who defected from captivity and fought against their own compatriots.

- ↑ resting phase

- ↑ which also indicates a cover-up of the matter

- ↑ Luis Trenker: Rocca Alta fortress. My time 1914–1918 . Josef Berg Verlag, Munich 1977, p. 73 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Joly: Standschützen . Universitätsverlag Wagner, Innsbruck 1998, pp. 16-25, 42-73.

- ↑ Fortunato Turrini (ed.): La Guerra sulle porta. Pejo 1998, pp. 17-18; Heinz von Lichem: War in the Alps, Vol. 1. Athesia, Bozen 1993, pp. 10-11.

- ^ CH Baer: The battles for South Tyrol and Carinthia. P. 58.

- ^ Elisabeth Petru: Patriotism and war image of the German-speaking population of Austria-Hungary 1914-1918 . Rough Diplomarb, Vienna 1988, pp. 69-70.

- ↑ Rudolf Jerábek: The Brussilowoffensive 1916. A turning point of the coalition warfare of the Central Powers . Rough Diss., Vienna 1982, pp. 538, 597; Robert A. Kann: On the problem of the nationality question in the Habsburg Monarchy 1848–1918 . In: Adam Wandruszka, Walter Urbanitsch (ed.): The Habsburg Monarchy 1848–1918, Volume 3: The peoples of the empire , 2nd volume. Vienna 1980, ISBN 3-7001-0217-8 , pp. 1304-1338, p. 1335.

- ^ Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the First World War. P. 13.

- ^ Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the 1st World War. Vienna 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ In Germany called "Zeltbahn"

- ^ Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the First World War . Verlag Militaria, Vienna 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Vasja Klavora: Monte San Gabriele . Verlag Hermagoras / Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt 1998, p. 139 ff.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner: Armed Forces (Austria-Hungary). In: Gerhard Hirschfeld (ed.): Encyclopedia First World War. Schöningh, Paderborn / Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-8252-8396-4 , pp. 896-900.

- ↑ from these an association with division strength could already be set up

- ^ Heinz von Lichem: Spielhahnstoss and Edelweiss. Stocker Verlag, Graz 1977, p. 247.

- ↑ a b cf. US map to battle

- ^ From a speech by Mussolini in front of the victory monument in Bozen on November 4, 1930 from: Giancarlo Taretti: Benito Mussolini - Duce del Fascismo. Roma 1937, p. 188.

- ^ Giuseppe Prezzolini, Vittorio Veneto. Rome, La Voce. 1920, p. 34.

- ^ Jan F. Triska: In the war on the Isonzo. From the diary of a soldier at the front. Verlag Hermagoras / Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt 2000, ISBN 3-85013-687-6 , p. 177 ff.

- ^ Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the 1st World War. Vienna 2002, p. 23.

- ^ Edmund Glaise-Horstenau , in: The Austro-Hungarian War. Barth, Leipzig 1922, p. 634.

- ↑ Glaise-Horstenau, p. 635.

- ↑ Hans Magenschab: The War of the Grandfathers 1914-1918. The forgotten of a great army. Verlag der Österreichische Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1988, p. 212.

- ^ Camillo Ruggera in: International Encyclopedia of the First World War (English) accessed on May 15, 2018.

- ^ Wolfdieter Bihl : The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy 1917/18. In: Karl Gutkas (Hrsg.): The eight years in the Austrian history of the 20th century. (= Writings of the Institute for Austrian Studies, Volume 58), ÖBV Pädagogischer Verlag, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-215-11575-1 , pp. 28–53, here: p. 52.

- ^ Rest-Ortner-Ilmig: The emperor's rock in the 1st World War. Vienna 2002, p. 23.

- ↑ Johann Christoph Allmayer-Beck : The Army History Museum Vienna. The Museum and its Representation Rooms , Salzburg 1981, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner , Manfred Litscher (Ed.): The Army History Museum in Vienna. Graz / Vienna 2000, pp. 64–71.