Mountain War 1915–1918

Italian Front

| date | May 23, 1915 to November 4, 1918 |

|---|---|

| place | Eastern Alps |

| output | Victory of the Entente |

| Territorial changes | South Tyrol , Trentino , Canal Valley , Istria |

| Peace treaty | Treaty of Saint Germain |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

Luigi Cadorna (1915-1917) |

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (1915–1917)

|

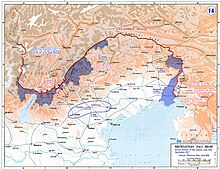

The front of the mountain war between Austria-Hungary and Italy in World War I (Italian Guerra Bianca ) ran from 1915 to 1917 from the Stelvio at the Swiss border on the Ortler and Adamello to the northern lake , east of the Adige then the Pasubio , continue on the seven municipalities , the Carnic ridge and the Julian Alps to Gradisca . 1915 - even before the state of war between Germany and Italy - came to the Alpine Corps and German troops are used. The Germans were not yet allowed to cross the Italian border - even if the artillery was already firing into Italy.

Starting position

Before the outbreak of World War I, Italy belonged to the so-called Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and the German Empire . In 1914, the country refused to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers on the grounds that the Triple Alliance was a defensive pact. There is only an alliance obligation if one of the allies is attacked, but according to the Italian view, Germany and Austria-Hungary have started the war.

The real reason was that the Entente made promises to Italy from the start that corresponded to the aspirations of the Italian Irredenta . In Friuli and South Tyrol, as well as in Trentino and Trieste , Italian minorities of different strengths lived, and the Entente promised these Austrian areas to Italy on their side in the event that it entered the war. Austria pointed out that there were more Italians as a minority in France and Switzerland , but was not heard. Another reason for this was probably that Italy viewed Austria as their supposedly weaker opponent. There were plans in the Italian General Staff to advance to Vienna within four weeks . The Italian economy was also not interested in fighting on the side of the Central Powers. The Italian economy was very dependent on raw material imports by sea, which would have been blocked in the event of a war against the Entente.

The Italian population, however, was by no means enthusiastic about the war and first had to be motivated by means of propaganda . The poet Gabriele d'Annunzio , who knew how to create an anti-Austrian mood, stood out here. General Luigi Cadorna also succeeded in getting Parliament to his side with optimistic promises and forecasts. He was an accomplished speaker, but had little military skills. The Austrian border was well fortified in anticipation of the Italian entry into the war, but only manned by weak Landsturm units . For some sections of the front, no kuk troops were available at all at the beginning . Here, volunteers marched from peak to peak at night, using many torches to pretend a stronger occupation. General Cadorna shied away from any risk or a swift offensive. The Austrians, for their part, finally brought reinforcements from the Serbian and Russian fronts to the Italian border and thus managed to organize a closed defense within two weeks.

Even before the war, Austria had extensive fortifications built on the border with Italy , in the expectation that the treaty of alliance with Italy would not hold. After Italy's entry into the war was delayed, the fortifications were occupied by the Landwehr .

The German allies helped the Danube Monarchy: the newly established Alpine Corps was moved to South Tyrol in May 1915 and stayed there until autumn. From August 1916 Germany was formally at war with Italy. The mountainous terrain opposed a rapid Italian advance and favored the defenders.

At the beginning of the war, Italy had an army of 900,000 men, which was divided into four armies and the Carnic group. The commander-in-chief was General Luigi Cadorna . The established plan of operations provided for the 2nd and 3rd Armies to advance across the Isonzo River in the direction of Ljubljana in order to enable strategic cooperation with the Russian and Serbian armies. The Carnic group was to advance towards Villach in Carinthia , the 4th Army was to attack Dobbiaco . The 1st Army deployed against South Tyrol should behave defensively. Already in the first few weeks it became apparent that the planned surgical goals were completely unrealistic.

The theater of war

The front was for the most part in mountainous terrain and therefore made special demands on the conduct of the war (cf. mountain war ). Literally every water bottle and every piece of firewood had to be transported to the positions by mules or porters. As from the winter of 1916/17 onwards the horses and mules were hardly able to perform due to a lack of feed, they were increasingly replaced by electrically operated cable cars and train connections.

The shortest connection to Carinthia or northern Slovenia was also blocked by forts built during the Napoleonic period (e.g. Fort Hermann or Herrmannswerk). However, the Austro-Hungarian army command was aware that these barriers would not withstand fire with modern explosive shells. The guns and crews of these forts had therefore been withdrawn before the outbreak of war, with the exception of a minimal remaining crew who pretended to be full. The Italian troops were stopped in front of these forts and the Italian artillery shot down the forts, giving the Austrian army the time it needed to build its defensive lines.

On the Isonzo and in the direction of Trieste , the terrain was rather hilly and karstified and therefore open to major attacks. As a result, the Italian attacks repeatedly focused on this section. In particular, the only two Austrian bridgeheads west of the Isonzo, near Tolmein and Gorizia, were attacked several times. Here, however, Cadorna's military awkwardness became apparent: Although the Italians had an elite unit specially trained for mountain warfare with a high level of corps spirit, with the Alpini , and multiple superiority with conventional forces, while on the other hand, at best, second-rate units made up of old and very young men Scarcely any equipment was available, Cadorna hesitated. This gave the Austrians time to introduce regular units and build a modern, deep line of defense.

General Cadorna initially preferred a conservative, outdated attack tactic. So his soldiers proceeded in a tightly packed and staggered manner, which all other warring countries had long avoided because of the extraordinarily high losses caused by machine gun fire of the defenders. In addition, Cadorna was too hesitant and often gave away already won initial successes. In addition, there was an extremely brutal style of leadership, in which defeats were only due to the soldiers' lack of "morale" and not to the planning or the terrain. In addition, Cadorna was very negative about regularly changing the front units. Even letters from home would only "soften" the soldiers, although the soldiers often eagerly awaited the field post. Cadorna's way of thinking can be at least partially traced back to the frequent supply problems of the Italian army. Cadorna's style of leadership and his tendency to pointless and costly attacks led to several mutinies that were bloodily suppressed.

The Austrians, for their part, had sent one of their most capable commanders to the Italian front, Colonel-General Svetozar Boroević von Bojna . Above all, the defensive was one of his specialties; he managed again and again to prevent an Italian breakthrough despite being clearly inferior to an opponent that was up to three times stronger. His skill soon earned him the nickname “the lion of the Isonzo”. On 1 February 1918 he was of Emperor Charles I to Field Marshal transported.

Due to the enormous hardships and privations, both sides had to struggle with discipline problems and even desertion . In the Austro-Hungarian Army , especially Czech units were badly affected. The nationalism and the promotion of a separate Czech National State started by the Entente to take effect. The poor supply situation for the Austro-Hungarian units did the rest to lower morale .

In the case of Italian units, the difference (which still exists today) between northern and southern Italians was often the reason for defection to the enemy. Southern Italians often viewed the war as a "war of Rome and the north" that did not concern them.

The forces of nature threatened the soldiers on both sides with particular dangers . On some sections of the front, more soldiers were killed by avalanches , rockfalls and accidents than by enemy fire (→ avalanche disaster of December 13, 1916 ). Mine warfare was also waged again - sometimes in difficult terrain: enemy positions (sometimes even entire mountain peaks) were undermined, undermined and blown up . The best known example is the Col di Lana . Snow or stone avalanches were also deliberately triggered above enemy positions by fire.

Front course

While holding battles were fought in the Dolomites on the Austro-Hungarian side (with the exception of the South Tyrol offensive 1916 and the offensive known as the Avalanche company ), the main events took place in the Carnic and Julian Alps . The Isonzo and Piave battles particularly stood out here.

Only after the successful campaign against Serbia and Montenegro in autumn 1915 did Austria have the opportunity to take an offensive against Italy. An offensive by two Austrian armies was planned, starting from the Lavarone plateau in the direction of Venice. Due to unfavorable weather conditions, the attack could not begin until May 15, 1916, which meant that the surprise effect was lost. Despite the difficult terrain, the offensive achieved initial successes, but soon got stuck. The Russian Brusilov offensive that began in early June 1916 finally forced the Austrians to cease the attack.

The Austrian spring offensive that took place in 1916 in the area of the seven municipalities was unsuccessful.

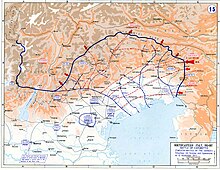

Only on the Carinthian and Isonzo fronts was it possible to convert positional warfare into war of movement. The gas attack by the Austro-Hungarian Army near Flitsch / Plezzo / Bovec at the beginning of the 12th Isonzo battle on October 24, 1917 also led to the collapse of the Italian front in the high mountains, a success that brought the Austro-Hungarian Army with its allied German troops to the Tagliamento first and continued to the Piave.

The mountain front between the Stilfser Joch and the Piave continued until 1918. The southern section of the Austrian mountain front collapsed in late October 1918 after the battle of Vittorio Veneto .

Acts of war

On May 23, 1915, Italy entered the First World War despite the alliance on the side of the Entente against Austria-Hungary. In the manifest of May 23, 1915 To My Peoples! said Emperor Franz Josef: “The King of Italy has declared war on me. A breach of loyalty, the likes of which history does not know, was committed by the kingdom of Italy to its two allies. ”At the beginning of the war, Italy had an army of 900,000 men, which was divided into four armies and the Carnic group. The commander-in-chief was General Luigi Cadorna . The established plan of operations provided for the 2nd and 3rd Armies to advance across the Isonzo River in the direction of Ljubljana in order to enable strategic cooperation with the Russian and Serbian armies. The Carnic group was to advance towards Villach in Carinthia , the 4th Army attacked Dobbiaco . The 1st Army deployed against South Tyrol should behave defensively. Already in the first few weeks it became apparent that the planned surgical goals were completely unrealistic. This was due on the one hand to the difficult terrain and lack of artillery, on the other hand, however, also to the completely erratic behavior of the Italian high command, which preferred direct frontal attacks on heavily buried opponents. The Italian soldiers were so heavily shelled by Austrian machine guns and artillery that the offensives all collapsed except for marginal successes. In contrast to the Italians, the Austrians already had war experience and knew how important a well-fortified position and artillery superiority were. This was somewhat offset by General Hötzendorf , who like Cadorna had a tendency towards mass attacks with great losses and on whose initiative several failed offensives by the Austrians were backed up, which ensured that the Austro-Hungarian army was just as capable of the conquered territory at the end of the war to keep.

Until October 1917, the front ran north through the Dolomites and then east through the Carnic Alps . In the Julian Alps it ran essentially along today's Italian-Slovenian border and along the Isonzo to the south. To the south of Gorizia , several battles took place on the karst plateau east of the Isonzo countercourse (1st – 12th Isonzo battle), from where the Italian army wanted to advance towards Trieste and Ljubljana . The front line ended at Duino on the Adriatic . All in all, it was an approx. 600 km long front (as the crow flies ) that ran between Switzerland and the Adriatic in the form of a lying "S". Most of the front was in the high mountains, which is why the aforementioned 600 km have to be extended by several hundred kilometers for topographical reasons.

From October 1917 to October 1918, after the Battle of Karfreit (12th Isonzo Battle) , the front ran from the plateau of the Seven Municipalities over Monte Grappa and in the lowlands along the Piave to the Adriatic Sea.

Museum reception

The mountain war is documented in a separate area in the Army History Museum in Vienna. Among other things, uniforms, camouflage clothing, glacier goggles, infantry guns and machine guns are on display, including a 7 cm M 1899 mountain cannon , which was positioned in the summit zone of the Ortler at 3,850 meters and was the highest gun position in Europe.

The Kobarid Museum is dedicated to the Isonzo battles , in particular the Battle of Good Freit, at a historic location . In 1993, the museum was awarded the Council of Europe Museum Prize for the remarkable exhibition.

The Museum 1915–18 , which opened in 1992 in the town hall of Kötschach-Mauthen and has since received several awards, shows the high mountain front from the Ortler to the Adriatic with numerous photos, exhibits and documents. The initiator of the Friedenswege and founder of the Dolomitenfreunde Oberst iR Prof. Walther Schaumann and his international volunteers also built the open-air museum of the mountain war on the Plöckenpass . With its fortifications, trenches and caverns, this is intended to show visitors the everyday life of soldiers during the First World War.

Also worth mentioning are the War Museum Rovereto and the other museums and memorials in Trentino that are part of the Rete Trentino Grande Guerra network .

See also

- kk mountain troop

- Austrian fortifications on the border with Italy

- Friedensweg - long-distance hiking trail that opens up the positions of the Alpine War

literature

- Austrian Federal Ministry for the Army ; Vienna War Archives (ed.): Austria-Hungary's last war 1914–1918. 1931 from the Verlag der Militärwissenschaftlichen Mitteilungen , Vienna (archive.org) .

- Alexander Jordan : War for the Alps. The First World War in the Alpine region and the Bavarian border guard in Tyrol (= contemporary historical research . Vol. 35). Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-428-12843-3 (with a detailed description of the state of research and literature).

- Wolfgang Etschmann : The Southern Front 1915–1918. In: Klaus Eisterer, Rolf Steininger (Hrsg.): Tyrol and the First World War. (= Innsbrucker Forschungen zur Zeitgeschichte, Volume 12), Vienna / Innsbruck 1995, pp. 27–60.

- Hubert Fankhauser, Wilfried Gallin: Undefeated and yet defeated. The mountain war on the Carinthian border, 1915–1917. Publishing bookstore Stöhr, Vienna, 2005.

- Ingomar Pust : The stone front. From the Isonzo to the Piave. On the trail of the mountain war in the Julian Alps. Ares Verlag , Graz, 3rd edition 2009. ISBN 978-3-902475-62-6 .

- Walther Schaumann: Scenes of the Mountain War in 5 volumes. Ghedina & Tassotti Editori, Cortina 1973.

- Gabriele and Walther Schaumann : On the way from the Plöckenpass to the Canal Valley. On the trail of the Carnic Front, 1915–1917. Verlag Mohorjeva - Hermagoras, Klagenfurt 2004 (with tour guide)

- The lonely war. Hornung, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-87364-031-7 , Athesia, ed. 2-7, Bozen 1976-2007, ISBN 978-88-7014-174-0 .

- Heinz von Lichem : Spielhahnstoss and Edelweiss. The peace and war history of the Tyrolean high mountain troops "The Kaiserschützen" from their beginnings to 1918. Kk Tiroler Landesschützen-Kaiserschützen Regiments No. 1, No. 2, No. 3. Leopold Stocker Verlag , Graz 1977, ISBN 3-7020-0260 -X .

- Heinz von Lichem: The Tyrolean High Mountain War 1915–1918 in the air. Steiger, Innsbruck 1985, ISBN 3-85423-052-4 .

- Heinz von Lichem: Mountain War 1915–1918. 3 volumes, Athesia, Bozen.

- Ortler, Adamello, Lake Garda. (Volume 1) 1996, ISBN 88-7014-175-6 .

- The Dolomite front from Trento to the Kreuzbergsattel. (Volume 2) 1997, ISBN 88-7014-236-1 .

- Erwin Steinböck: The battles for the Plöckenpass 1915/17 . Military historical series, issue 2. Österreichischer Bundesverlag Gesellschaft mb H., Vienna 1988, ISBN 3-215-01650-8 .

- Uwe Nettelbeck : The Dolomite War . Two thousand and one: Frankfurt am Main 1979. A new edition appeared in 2014, illustrated and with an afterword by Detlev Claussen. Berenberg Verlag, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-937834-71-9 .

- Oswald Übergger : The Myth of the Mountain War, or: How Tyroleans became heroes . In: Hannes Obermair u. a. (Ed.): Regional civil society in motion. Festschrift for Hans Heiss (= Cittadini innanzi tutto ). Folio Verlag, Vienna-Bozen 2012, ISBN 978-3-85256-618-4 , p. 602-625 .

With a focus on those involved in the war:

- Walter Gauss: Crosses in Ladin in the heart of Ladin. Athesia, Bozen 2000.

- Vasja Klavora: Plavi Križ. Mohorjeva založba, Celovec / Ljubljana / Dunaj 1993 (Slovenian).

- Nicola Labanca, Oswald Übergger (ed.): War in the Alps. Austria-Hungary and Italy in the First World War (1914–1918). Böhlau Verlag, Vienna – Cologne – Weimar 2015, ISBN 9783205794721 .

- Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 .

- Mark Thompson: The White War. Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919. Faber and Faber, London 2008. ISBN 978-0-571-22333-6 (English, focus on events in the Italian army).

- Immanuel Voigt: Testimonies from the Dolomite Front 1915. The Alpine Corps in pictures, reports and biographies. Verlag Athesia-Tappeiner, Bozen 2017, ISBN 978-88-6839-288-8 .

Novels with the scene of a mountain war:

- Ernest Hemingway : A Farewell to Arms . First edition: Jonathan Cape Limited, 1929. Arrow Books, London 1994.

- Luis Trenker : Mountains on fire . A novel from the fateful days of South Tyrol. 1931.

- Erik Durschmied : Dance of Death at Col di Lana - Battle for the blood mountain of the Dolomites. Verlag Athesia-Tappeiner, Bozen 2017, ISBN 978-88-6839-268-0 .

Web links

- Pictures from the battlefields of the Southwest Front 1915–1918

- Storia ed itinerari della Grande Guerra 1915–1918… “per non dimenticare” ( history and routes of the First World War 1915–1918… “not to be forgotten” ) on www.cimeetrincee.it (Italian)

- Rupert Gietl: The Austro-Hungarian emplacements on top of Mt. Roteck (2390m) Dolomites / South-Tyrol , Budapest 2012 (English)

- War in the Dolomites (Italian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stefan Reis Schweizer: A War in Ice and Snow In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of January 17, 2018.

- ^ Manfried Rauchsteiner , Manfred Litscher (Ed.): The Army History Museum in Vienna. Graz, Vienna 2000, p. 32.

- ^ Museo Storico Italiano Della Guerra .

- ^ Rete Trentino Grande Guerre (Ed.): The museums and the First World War in Trentino . Rovereto 2014; ( Trentino Grande Guerra ).