Mine Warfare

The Mine War was a battle tactic siege of fortresses or expanded, fortified field positions. Initially, the attacker only drove underground tunnels under the enemy's fortifications - they were undermined . After completion, the supporting wooden beams were either set on fire or pulled out on ropes. As a result, the tunnels collapsed and the walls and buildings above collapsed or were damaged.

After the appearance of black powder , large quantities of explosives were also detonated under the opposing positions - some of the quantities used amounted to 100 tons and wreaked enormous havoc.

The term mine later generally referred to military explosive devices that, unlike bombs or grenades, worked from a fixed location.

technology

In previous wars , mine warfare was mainly used to breach the fortress walls for a planned assault . As part of the preparation for the attack on a fortress, the soldiers began digging covered paths, which were trenches up to ten meters wide and two meters deep. "Covered" meant privacy protection against the city defenders. These trenches were mostly zigzagged, so the protection was better. The closer the trenches came to the city's outer defenses, the more the covered path led down. It started the Sappenvortrieb (running or digging approach). For this purpose, sappers or miners were used, in many cases forcibly recruited miners . Their knowledge of the tunnel construction was used. The outer facilities have been undermined as much as possible. In the vicinity of the curtain wall (main wall) Mini Development began. That means it was blown up.

The aim of the action was to collapse the ramparts. At the same time the artillery attack ran on the same points. The artillery attack caused the aforementioned facilities to be breached. The exploding mines came from below, the wall collapsed. Now the infantry had a chance to get into town.

enlightenment

Mines were cleared by water barrels or upturned empty barrels with raw hard-dried peas strewn on the bottom. When the peas vibrated or the water made waves, they were digging in the immediate vicinity.

Antidote

The walls had to have an extraordinarily deep foundation (ideally to below the water table) and the stones of the walls had to be laid in an arc shape so that when part of the foundations broke away, everything did not collapse. This form of masonry can also be seen today on the Ehrenbreitstein Fortress .

Nailed boards were buried in the area where mines were expected. If the miners came across these boards, they were prevented from advancing because they had to dig these boards out of the ground before they could continue digging. In addition, the vibrations of the boards (protruding from the earth) were easy to see, the hollow sound of the shovels on the boards nearby was easier to hear and clarify, and further countermeasures could be taken more easily.

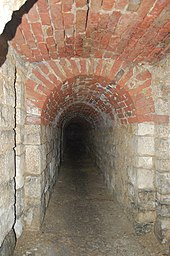

Another counter-tactic was the countermines. The besieged dug mine tunnels to meet the besiegers' miners. In later fortresses, mine galleries, with their underground tunnels reaching up to about 100 m from the fortress walls, were integrated as an integral part of the defense.

As soon as a listening post noticed the attacker's dig, countermeasures could be used:

- Introduce water into the enemy mines to make the enemy gunpowder unusable and, if possible, to drown the enemy, or at least to make it impossible to continue digging the tunnel.

- Rolling bombs down into them when they hit opponents. This caused the powder kegs used by the opponent to explode prematurely, the effect of the explosion struck back and ruined the opponent and his positions.

- to spill, crush or suffocate mine parts and their crew by counter-blasting.

- to divert the explosive force through the counter mines and to largely protect one's own fortress from the pressure of the explosion.

- to clear out completed explosive chambers before they are detonated and to render them harmless.

- to bump into the enemy and kill him in close combat.

- To create listening tunnels in order to recognize the new laying of a mine at an early stage, to be able to determine more precisely by means of several measurements at several locations and to use these listening tunnels for future countermines.

- To camouflage excavation activities elsewhere and to direct the countermines in the wrong direction.

Early mine wars

The first surviving mine trenches come from the Romans, the Fidenae 664 BC. BC and Veji 393 BC Chr. Conquered. The Jewish historian Josephus also reports of mine trenches which the besiegers of the city of Jerusalem around 39 BC. Chr. Caused severe problems. The first but unsuccessful attempt to blow up a powder-laden mine was made in 1487 by a Genoese engineer off Sorezanella. On the other hand, during the siege of the Castle dell 'Uovo near Naples, part of the rock on which the castle stood was blown up in this way.

During the siege of Candia (1648–1669), mine warfare reached a level that had not existed in history up to that point in time and that remained unique on this scale until the First World War .

Other well-known examples were the first and second Turkish sieges of Vienna in 1529 and 1683. The extremely cruel struggle that then developed took place in a confined space with cutting and stabbing weapons in order not to prematurely explode one's own powder stocks. Under Selim, the Turks were the first to deploy their own troops to mine.

In the Palatinate War of Succession (1688–1689), the siege of the fortresses was partly carried out as a mine war.

The military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633–1707) seems to have been the first to conduct thorough investigations into determining the appropriate strength of the mine charges.

This type of warfare was also used in the American Civil War (1861–1865). B. in the crater battle .

Mine warfare in World War I

The tactic of mine warfare was last used during the First World War, especially on the Western Front and the Alpine Front .

On the Alpine front, entire mountain peaks (including the respective crew) were blown away. The best-known examples of this form of war were the struggle between Italian and Austro-Hungarian troops over the Pasubio massif (largest single mine explosion of the First World War) and the Col di Lana . The different types of mine warfare can still be seen today at Little Lagazuoi . Kilometers of corridors were dug there and some were blown up.

Austro-Hungarian miners made a dangerous find on the Isonzo front in 1917 : They found a completely detonable mine made by the Italians while the tunnel was being built. Before it could be detonated, the Austro-Hungarian troops rendered it harmless and cleared the mine chamber. The captured explosives were then used in a counterblast.

On the western front z. T. whole villages (for example Vauquois in the Argonne ) destroyed. The Somme battle began on July 1, 1916 with the explosion of 19 mines that had been placed below the German positions. The bang could be heard even in London, earth and debris were thrown up to 1200 meters into the air. Two of these mines became particularly prominent: the Hawthorn Ridge mine explosion was filmed by British cameraman Geoffrey Malins and featured in the propaganda film The Battle of the Somme , while the Lochnagar mine detonated 26.8 tons of ammonal explosives huge crater ( Lochnagar crater ).

As a prelude to the Battle of Messines (June 7, 1917) another 19 mines were detonated with an average of 21 tons of ammonal explosives. This killed around 10,000 German soldiers in one fell swoop.

Sometimes it happened that both sides tried to undermine the opposing trenches at the same time. If the digging pioneers noticed that the enemy was planning to do the same, attempts were made to enclose or kill him with underground explosions. In 1917 there was a tacit cessation of the mine war on the Western Front.

Some of the mines laid were deliberately not ignited due to the changed course of the front and still pose a threat today. South of Messines, near the French border, a lightning strike triggered the explosion of one of these mines on June 17, 1955. A crater 40 m in diameter and 20 m deep was created. Since this mine was under a field, only one cow died. It is believed that there are three other mines in the immediate vicinity of the crater, one of them directly under a farm.

See also

literature

- The mine war in World War I from a blasting point of view. Reprint from the magazine for the entire gun and explosives industry, 1937. Survival Press (spiral binding).

- Robert Striffler: The mine war on Monte Cimone 1916-1918 (= series of publications on contemporary history of Tyrol. Vol. 13). Book Service South Tyrol Kienesberger, Nuremberg 2001, ISBN 3-923995-21-0 .

- Robert Striffler: The Mine War in Ladinia. 2 volumes. Book Service South Tyrol Kienesberger, Nuremberg;

- Col di Lana. 1915–1916 (= series on contemporary history of Tyrol. Vol. 10). 1996, ISBN 3-923995-11-3 ;

- Monte Sief 1916–1917 (= series on contemporary history of Tyrol. Vol. 11). 1999, ISBN 3-923995-17-2 .

- Klavora Vasja: Steps in the Fog. The Isonzo Front - Karfreit, Kobarid - Tolmein, Tolmin 1915–1917. Verlag Hermagoras, Klagenfurt u. a. 1995, ISBN 3-85013-375-3 .

- Klavora Vasja: Blue Cross. The Isonzo Front. Flitsch / Bovec. 1915-1917. Hermagoras u. a., Klagenfurt u. a. 1993, ISBN 3-85013-287-0 .

Web links

- Short, comprehensive article on the Battle of Vauquois

- Website of the association "LES AMIS DE VAUQUOIS ET SA RÉGION" (fr; de; en)

- Christoph Gunkel: Mine use in the First World War. “Gentlemen, we will change the geography!” In: one day . January 21, 2014.

Remarks

- ↑ Bellum 1, 348 [1] .

- ^ Daniela Angetter, Josef-Michael Schramm: About the mining war in high alpine rock and ice regions (1st World War, SW front, Tyrol 1915-1918) from an engineering geological point of view. Geo.Alp, Vol. 11, University of Innsbruck, 2014, 135–160 ( PDF 6.4 MB )

- ↑ Lochnagar Crater - The Official Site