First Turkish siege of Vienna

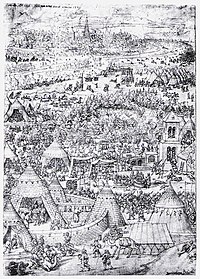

Vienna besieged by the Ottomans in the autumn of 1529 AD. In the foreground the tent castle of Suleyman I.

| date | September 27 to October 14, 1529 |

|---|---|

| place | Austria , Vienna |

| output | Withdrawal of the Ottoman army |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Philip the Arguable , Wilhelm von Roggendorf , Niklas Graf Salm |

Suleyman I the Magnificent |

| Troop strength | |

| about 17,000 | with entourage about 150,000 |

The First Siege of the Turks in Vienna or, more accurately, the First Siege of the Ottomans in Vienna was a high point in the Turkish Wars between the Ottoman Empire and the Christian states of Europe. It took place as part of the first Austrian Turkish War . From September 27 to October 14, 1529, Ottoman troops under the command of Sultan Suleyman I enclosed the Magnificent Vienna , which was then the capital of the Habsburg hereditary lands and one of the largest cities in Central Europe. Supported by other troops of the Holy Roman Empire , the defenders were able to hold their own.

background

With the capture of Adrianople in 1361 and the battles won at the Mariza in 1371, on the Amselfeld in 1389 and at Nikopolis in 1396, as well as the second battle on the Amselfeld in 1448, the Ottomans had proven to be an important military power on European soil. They were able to subdue large parts of the Balkan Peninsula and consolidate, expand and defend their rule there. After they had conquered Constantinople , the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire , in 1453 , their urge to expand, which brought them further areas of the Balkan Peninsula in rapid succession, became a permanent threat to the Western states.

Under Sultan Suleyman, who had ruled since 1520, the Kingdom of Hungary became the next target of the Ottoman expansion policy. In 1521, Suleyman succeeded in conquering Belgrade , which was then part of Hungary. In 1526 he won his decisive victory at Mohács over the Hungarian King Ludwig II , who fell in battle. On the basis of a contract of inheritance concluded in 1515, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria , the later Roman-German Emperor , raised claims on Bohemia and Hungary. At the Diet of Tokaj on October 16, 1526, however, part of the Hungarian nobility elected the voivode of Transylvania , Johann Zápolya , to be the Hungarian king. Ferdinand was then also elected King of Hungary on December 17, 1526. Zápolya placed itself under the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1528 and received military support against his rival, who initially had the upper hand in the controversy for the throne. In mid-1529, Sultan Suleyman moved into Hungary at the head of a large army and installed King John on the Hungarian throne in Buda , which he occupied . Hungary became a de facto Ottoman vassal state . After this success the Sultan led his army further northwest and advanced via Komorn and Pressburg to Vienna, which the Ottoman troops reached in September. Whether the goal was actually to conquer the " Golden Apple ", as the Ottomans called Vienna at the time, or just a demonstration of the strength with which Suleyman wanted to secure his gain in power over Hungary, is disputed in the research.

At that time, the military forces of the Habsburgs were largely tied up in Italy, where Emperor Charles V fought for European supremacy in long wars against the House of Valois . Archduke Ferdinand therefore tried to slow down the Ottoman advance with peace offers and promised the sultan and the greats of his empire regular gifts. At the Reichstag in Speyer in April 1529, with detailed descriptions of the atrocities allegedly perpetrated by the Ottomans in occupied Hungary, he succeeded in persuading the imperial estates to provide him with money and troops for defense, albeit not in the hoped-for extent. However, he did not receive a mandate to recapture Hungary, which the Archduke was actually striving for, and the fighters, who were paid with the money granted, were not allowed to cross the imperial border. Friedrich von der Pfalz was appointed as its commander .

course

Beginning

Suleyman I set out with a large force on April 10, 1529 from Constantinople. On the way through south-east Europe, his army grew by joining numerous garrisons . Hungarian fighters also joined him. The advance through Hungary was slowed as there was no road network and heavy rains had softened the ground. In September the harbingers of this army appeared in the vicinity of Vienna, a force of around 20,000 Akıncı . This unpaid light cavalry usually preceded the regular army by plundering, slaving, raping and murdering and was intended to cripple the will of the population to resist.

A large number of Viennese citizens fled from September 17, including seven out of twelve members of the city council. Only mayor Wolfgang Treu , the city judge Pernfuß and three other city councilors remained. Of the more than 3,500 armed citizens of the city militia , only 300 to 400 stayed behind. However, many refugees fell into the hands of the Akıncı on their way to supposedly safe territory.

Vienna was defended by the city garrison, the remnants of the city militia and several thousand German and Spanish mercenaries , including a hundred armored riders under the command of Count Palatine Philip , who arrived shortly before the siege ring was closed. The imperial troops decided by the Reichstag , a total of 1,600 horsemen, came too late and remained at Krems on the Danube . In total, the city's defenders were able to muster around 17,000 soldiers. The mercenaries were armed with pikes and arquebuses and had been able to familiarize themselves with advanced tactics during the Italian wars . However, the numerical superiority of the besiegers was considerable, and the protective value of Vienna's city wall built in the 13th century was insufficient.

On September 23, the Ottomans came within sight of the city, which was completely enclosed by September 27. Their armed force comprised around 150,000 people, some of whom were part of the entourage . The fighting part of the army comprised around 80,000 Ottoman soldiers and 15,000 to 18,000 soldiers from the Ottoman vassal states of Moldova and Serbia . In addition to numerous horsemen ( sipahis ), almost 20,000 Janissaries formed the core force. The condition of the Hungarian roads had prevented more than two heavy siege guns ( Balyemez /بال يماﺯ) could have been transported from Belgrade or Ofen to Vienna, so that only 300 lighter cannons were carried. On the way, the Ottomans also used around 22,000 camels as pack animals. The Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha was responsible for the tactical management of the siege .

As commander-in-chief of the two regiments of imperial troops in the city, Count Palatine Philipp played an essential part in the defense of the city of Vienna. In defense, he commanded the wall area from the Red Tower to the Kärntnertor bastion . Since the 19th century, for patriotic reasons, the achievements of the Viennese citizens and Niklas Graf Salm have been pushed more and more into the foreground, while Philip’s contribution has been forgotten.

Niklas Graf Salm and Hofmeister Wilhelm von Roggendorf had the city walls reinforced with earth fortifications and all but one of the gates walled up. The church bells were shut down, the 28 boats of the Danube flotilla were burned because their crew had fled and they should not fall into the hands of the Ottomans. They also oversaw the positioning of the 72 cannons available to the city's defenders. All buildings outside the city walls were torn down to allow a free field of fire and to deny the attackers opportunities for cover. However, this happened too late and too incompletely, so that the Ottomans found enough hiding places. On September 27th, Suleyman sent a delegation with two captive horsemen to the city, which suggested the Viennese surrender and in this case guaranteed them the sparing of the garrison and the population. If they refuse to capitulate, the Ottoman army will storm the city. The negotiators sent those trapped back to the camp without responding to their request.

Battle in the dark and Ottoman assaults

Ibrahim Pascha's plan was to undermine the Kärntnertor, which seemed to him to be the weakest point in the city's fortifications, and to shoot it ready for a storm. Süleyman approved the project on October 1, and the Ottoman artillery ( Topçu ) opened fire. Since it lacked heavy cannons, the hoped-for effect did not materialize. This was followed by attempts to undermine the Vienna city walls, while the cannons kept firing to distract attention. After a Christian defector had communicated the besiegers' plans to the defenders of Vienna, water tubs were set up in the houses near the city wall in order to identify enemy excavations early. The visible waves of the water signaled the underground approach of the Ottomans. The city garrison, reinforced by Tyrolean miners, dug out to meet them, and after a while they came across the Ottoman miners . Subterranean battles broke out in which firearms could hardly be used, as the miners carried barrels of gunpowder with them to carry out their mission . In these clashes, the better armored defenders gained the upper hand after a while, but not all Ottoman mines could be discovered. The attackers blew up several breaches in the Viennese city wall, which led to fierce fighting. The defenders built palisades behind the breaches, dug trenches and formed dense formations of pikemen and arquebuses , against which the janissaries could do little.

On October 12th, the Ottomans blew a particularly large breach in the Vienna city wall ("Sulaiman Breach"), which was followed by the largest Ottoman attack to date. Even in these battles the storm troops could not prevail and lost 1200 Janissaries alone. Late in the evening of the same day, Suleyman convened a council of war in his camp. The supply situation for the Ottoman army was extremely poor at this point, as supplies were held up by the completely sodden streets. The Akıncı's looting of the area now also took its toll. In addition, the onset of winter was imminent, which ruled out a longer siege. The Janissaries expressed their displeasure with the Sultan, whereupon they could be persuaded by Süleyman by the assurance of a large reward to carry out a final assault before the siege would be broken off due to the weather conditions. On October 14th, the Ottomans blew a breach in the Kärntnertor, but the rubble fell outwards, making the storm extremely dangerous. Again the pikemen of the defenders faced the Janissaries in close formation, so that they had to retreat again with heavy losses.

retreat

The importance of breaking off the siege for the Ottomans is controversial in the literature. The American military historian Paul K. Davis sees this as a clear defeat. The Leipzig medievalist Klaus-Peter Matschke, on the other hand, believes that despite the almost 20,000 deaths that were to be lamented on the Ottoman side, the Sultan did not see the result as a defeat. He did not blame the Grand Vizier or the commanding officers, on the contrary. In the diary of the campaign it is noted: “All Beys were given a pompous robe and were allowed to kiss the hand.” Ottoman historians even described the siege as a success and gave the weather situation as the main reason for the retreat, as stated in the headline of the adjacent miniature:

«سلطان سليمان خان بدوندن پچه واروب واروشن فتح و تسخير اتدكلرندن صكره قيش مانع اولمغين كيرو دونمشدر»

« Sulṭān Süleymān Ḫān Bedundan Peçe (Bėçe?) Varub vāroşun fetiḥ ve tesḫīr etdiklerinden ṣoñra ḳış māniʿ olmaġın gėrü dönmişdir »

“Sultan Suleyman Chan arrived in Vienna from Ofen ; after he had conquered and subjugated the suburbs, he returned because of the obstructive winter. "

On the night of October 15, the withdrawal began. The troops left everything behind that prevented them from withdrawing.

In Vienna, on the other hand, the bells rang for the first time in almost three weeks , and a Te Deum was prayed in St. Stephen's Cathedral . The mercenaries of the Reich troops who had still arrived mutinied outside Vienna because they did not receive the five-fold "storm pay" that was demanded despite their inactivity. Count Palatine Friedrich and his troops did not even think of a pursuit of the withdrawing Ottoman army, which the light cavalry of mercenary leader Hans Katzianer had already undertaken , also because they were forbidden to cross the imperial borders. For them it was about money: only after two weeks of negotiations could the servants, who had even threatened to storm and loot Vienna, be persuaded to accept lower pay. Some imperial troops under Niklas Graf Salm and Wilhelm von Roggendorf secured the eastern border by occupying Ödenburg , Hungarian-Altenburg , Bruck an der Leitha , Hainburg an der Donau and Pressburg . Niklas Graf Salm died in May 1530 of an injury sustained while defending the city. Ferdinand donated a Renaissance altar for him, which can be seen today in the baptistery of the Vienna Votive Church, which was completed in 1853 .

consequences

The withdrawal of the Ottomans brought the Habsburg capital security for over 150 years. Sultan Süleyman made a second attempt to conquer Vienna in 1532, but this time the defenders were better prepared: Süleyman's troops were thrown back and defeated in the battle in the Fahrawald . Emperor Charles V reached an agreement in good time with the Protestant imperial estates in the Nuremberg religious peace and was thus able to counter the invaders with an army of approximately 80,000 men. In addition to the imperial troops, soldiers from the non-German parts of his empire were also represented, from Spain, Italy and the Netherlands. The Ottoman troops therefore did not dare to advance on Vienna, but instead, after the unsuccessful siege of Güns, marched into Styria and plundered. In 1533 both parties signed a peace treaty that divided Hungary: the Habsburgs kept the so-called Royal Hungary , the rest had to be ceded to the Ottoman Empire .

The first and second Turkish sieges of Vienna in 1683 marked strategically and logistically the extreme limit of the Ottoman operational capability and the time of the greatest "Turkish threat".

reception

The siege of Vienna was followed with eager attention all over Europe. Oral reports from eyewitnesses, as well as leaflets and bound prints, as well as prints and songs, played a major role. As early as 1529 a chronicle of the Imperial Court Councilor Peter Stern von Labach was published, in which the atrocities of the Akıncı are described several times very drastically:

"VN what vnmēschlicher grausamkhait Sy Tu e rkhen bask with de Crist Lichen volkh needed is nit mu s possible to o Write / How to alleñthalbn dan in the Wa e lden / pergn / VN on the streets / in gantzn Leger / erslagn leutt / the child gehawn of each other or to the stekhendt Spissen / the Swangern weibern the Frücht from the physical geschnittn UN NEBn the mu o LEAVES of erbarmkhlich to o see is above eye time wasting UN found will. "

Such “ horror tales ” were one of the topoi that determined the Christian assessment of the “Turks”, as the Ottoman attackers in Europe were called. They also play a role in the Ottoman self-assessment as reflected in Turkish folk tales. The stereotypical portrayal of Suleyman I as the “cruel tyrant and hereditary enemy of Christian glavens” played a part in this image, which was widespread in printed matter well into the 17th century.

Martin Luther dedicated two treatises to the events in which he describes the Turks as “God's rod and plague”, which one has to “take God out of hand” through repentance , but also through war. At the same time, however, in the spirit of his doctrine of the two kingdoms, he strictly opposed religious exaggeration of war and ideas of the crusade . News of the end of the siege spread quickly and was received with great relief across Christian Europe. The nimbus of the almost invincible Ottomans had been broken for the first time. The threat from the Muslims and the victory were depicted in stories and works of the fine arts, some of which were imaginatively decorated, for example in the large-format battle panorama by Pieter Snayers (1592–1676).

Although the myth of the heroic struggle of the Viennese on the walls and underground was outshone in later centuries by that of the second siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1683, the memory of the danger of 1529 was still alive in the seventeenth century. When in 1686 a crescent moon, which had already been attached in 1519 and could rotate around an eight-pointed star, was removed from the top of St. Stephen's Cathedral, along with the star, the engraver Johann Martin Lerch engraved an envious fig and the year “A. o 1529 ”on it and below it the sentence“ Haec Solymanne Memoria tua ”- loosely translated:“ This, Süleyman, to your memory ”. The original meaning of the tower tower is still unclear today. In the 16th and 17th centuries, German-speaking and Turkish legends were formed that jointly assume that Süleyman initiated the installation directly or indirectly in 1529.

Sources and literature

swell

- Ten reports on the Turkish siege of Vienna in 1529 . In: Sylvia Mattl-Wurm u. a. (Ed.): Viennensia . Promedia, Vienna 2005, ISBN 3-85371-245-2 ( reprint of ten templates from the Vienna City and State Library - published between 1529 and 1532 - “A thorough and accurate report on what is new in the MDXXIX Jar between those in Vienna and Türcken ran away and reported from day to day clergy and wrote Tirckische occupation of the princely city of Vienna and how it fared the lucid, high-priced princes and mr. Wilhelmen and the Ludwigen brothers hertzog in Obern and Nidern Bairn Pfaltzgraffen Rein etc. zu Eern ” ).

literature

- Günter Düriegl (editor), Historical Museum of the City of Vienna (editor): Vienna 1529. The first Turkish siege. Text volume of the 62nd special exhibition of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Vienna, Cologne, Graz 1979, ISBN 3-205-07148-4 .

- Walter Hummelberger : Vienna's first siege by the Turks in 1529 (= Military History Series, Issue 33). Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1976, ISBN 3-215-02274-5 .

- Jan N. Lorenzen: The great battles. Myths, people, fates. Campus Verlag , Frankfurt am Main, New York 2006, ISBN 3-593-38122-2 , pp. 17–54: 1529 - The Siege of Vienna .

- Klaus-Peter Matschke: The cross and the half moon. The history of the Turkish wars. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-538-07178-0 , pp. 243–249.

- Hans-Joachim Böttcher : The Turkish Wars in the Mirror of Saxon Biographies. Gabriele Schäfer Verlag, Herne 2019, ISBN 978-3-944487-63-2 , pp. 28-29.

TV documentaries

- 1529 - The Turks before Vienna. MDR, Germany 2006.

Web links

- First Turkish siege (1529). In: geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at, accessed on September 9, 2019.

- Jan von Flocken: 1529: The siege of Vienna by the Turks. In: Die Welt from June 8, 2007, accessed on September 9, 2019.

- Karl August Schimmer: Vienna's sieges by the Turks and their invasions in Hungary and Austria. Vienna 1845, description of the siege on Google Books .

- WFA Behrnauer: Sulaiman the legislature's diary on his campaign to Vienna. Vienna 1858, Suleyman I's campaign diary against Vienna .

- Illustration by Johan Sibmacher from 1665: Conterfactur how the capital Vienna in Austria is occupied by Turcken, Anno 1529. ( digitized ).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Peter Csendes , Ferdinand Opll (Ed.): Vienna. History of a city. Volume 1: Vienna. From the beginning to the first Turkish siege of Vienna (1529). Böhlau, Vienna 2001, ISBN 3-205-99266-0 , p. 187.

- ^ Eva Maria Müller: Austria and the Ottomans: History lessons in the new middle school in Graz . Diploma thesis, University of Graz - Institute for History, Supervisor: Klaus-Jürgen Hermanik, Graz 2015, p. 31ff. on-line

- ↑ Ljubiša Buzić, interview partner: Simon Inou: An end to the “Turkish siege”. In: KOSMO. Twist Zeitschriften Verlag, March 21, 2014, accessed on September 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi: History of the Ottoman Empire. 3rd, through and updated ed., Munich 2004, pp. 16-19 and 33-37.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 5th edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2008, p. 119.

- ↑ a b c Klaus-Peter Matschke, 2004, p. 248.

- ^ Karl Weiss: History of the City of Vienna. Volume 2, Vienna 1883, p. 43.

- ↑ Günter Düriegl: The first Turkish siege. In: Günter Düriegl (editor), Historical Museum of the City of Vienna (editor): Vienna 1529. The first Turkish siege. Text volume of the 62nd special exhibition of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1979, ISBN 3-205-07148-4 , p. 7 ff.

- ^ Hans Bisanz: Vienna 1529 - From event to myth. In: Günter Düriegl (editor), Historical Museum of the City of Vienna (editor): Vienna 1529. The first Turkish siege. Text volume of the 62nd special exhibition of the Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, Verlag Hermann Böhlaus Nachf., Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1979, ISBN 3-205-07148-4 , p. 83 ff.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Matschke, 2004, p. 247.

- ^ Géza Fehér: Turkish miniatures . Leipzig and Weimar 1978, Commentary on Plate XVI

- ^ Paul K. Davis: Besieged. 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 2001, p. 101.

- ↑ Heinz Schilling: Departure and Crisis. Germany 1517-1648. Siedler Verlag, Berlin 1994, p. 224.

- ↑ Jonathan Riley-Smith : The Oxford History of the Crusades. Paperback, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 256.

- ↑ Şenol Özyurt: The Turkish songs and the image of the Turkish in German folk tradition from the 16th to the 20th century. Munich 1972, pp. 17-20.

- ↑ Peter Stern von Labach: Occupation of the instead of Wienn jm jar When one counts after Cristi's birth a thousand five hundred and in the twenty-newth annotation recently. Vienna 1529, Wikisource

- ^ Monika Kopplin: Turcica and Turqerien. On the development of the image of the Turks and the reception of Ottoman motifs from the 16th to the 18th century. In: Exotic Worlds - European Fantasies. Exhibition catalog, ed. from the Institute for Foreign Relations and the Württembergischer Kunstverein, Edition Cantz, Ostfildern 1987, p. 151 f.

- ↑ Nicolae Jorga: The history of the Ottoman Empire presented according to sources. Unchanged new edition, Primus Verlag Darmstadt 1997, vol. 1, p. 480 ff.

- ↑ Richard F. Kreutel: In the realm of the golden apple. Graz et altera 1987, pp. 28-52.

- ^ Sylvia Mattl-Wurm, 2005, p. 192.

- ↑ Hartmut Bobzin: "... I've seen the Alcoran in Latin ...". Luther to Islam. In: Hans Medick and Peer Schmidt (eds.): Luther between cultures. Vandenhoeck and Rupprecht, Göttingen 2004, p. 263ff.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Matschke, 2004, p. 389.

- ^ Anton Faber : Bulletin of the Vienna Cathedral Conservation Association. Episode 2/2006. P. 12 (PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ^ Karl Teply: Turkish sagas and legends about the imperial city of Vienna. Wien et altera 1980, pp. 50-56.

- ↑ sent to Arte on October 9 and 10, 2010 Archive link ( Memento of the original from September 25, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Further information on the documentation on Hannes Schuler's homepage: Archive link ( Memento of the original from September 21, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 136 kB)