Siege of Candia

| date | May 1, 1648 to August 25 / September 4, 1669 |

|---|---|

| place | Candia (now Heraklion) , Crete |

| output | Venice capitulates and is given free travel |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| unknown | unknown |

| losses | |

|

120,000 |

30,000 |

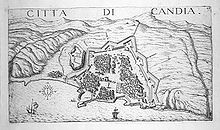

The siege of Candia (today: Heraklion ) by troops of the Ottoman Empire was the last battle of Venice in the war for Crete and one of the longest known sieges in history. It was maintained for over 21 years, from May 1, 1648 until the city surrendered on August 25, July. / 4th September 1669 greg. .

Starting position

The trade of the Colony of Crete with Venice was exposed to Turkish pirate raids, and this prompted Venice to build stronger fortifications to protect the coastal towns. According to the plans of the Veronese architect and builder Michele Sanmicheli , the extensive fortresses of Candia were built from 1523, from 1536 the city wall of Canea ( Chania ; not to be confused with Candia = Heraklion ) with several bastions and finally the great fortress of Rethymno was reinforced in 1540 .

In 1573 a new fortress was completed on the island of Agios Nikolaos in the bay of Souda, in 1579 on the island of Spinalonga in the Mirabello bay and in 1584 on the offshore island of Gramvoussa in the far west; by 1585 two fortresses were built on Agii Theodori in the bay of Chania.

After a Turkish fleet invaded the Adriatic in 1638 and shortly afterwards withdrew to the Ottoman port of Valona , Venice attacked the city, captured the pirate fleet and freed 3,600 prisoners. This led to preparations for the conquest of Crete at the Sublime Porte .

Ottoman invasion of Crete

Towards the end of the Thirty Years' War on mainland Europe, a new war began in the Mediterranean area after a long period of peacefulness. In 1644, the Knights of Malta attacked a Turkish convoy that was en route to Constantinople from Alexandria. The Maltese brought their booty to Crete. They also captured several pilgrims to Mecca. As a result, a Turkish fleet with 60,000 Ottoman soldiers under Sultan İbrahim I set sail for Crete in June 1645 , and shortly afterwards a Turkish army threatened Dalmatia .

The Turkish attack on Crete began in June 1645 with the capture of the fortresses on Agii Theodori off the north coast of western Crete and, after a siege of several weeks, on August 22, 1645 with the conquest of the city of Canea . The Turkish troops moved further east by land , and the Ottoman fleet also attacked the Rethymno fortress in September 1646 , which fell on November 13, 1646 after a siege of several weeks.

In order to be able to wage such a war, Venice needed troops that it could not raise itself, and so it recruited mercenaries from all over Europe, above all 30,000 men from Hanover , Braunschweig and Celle . Most were Thirty Years War veterans who had no use after the war and who had become a financial burden on the princes and cities they had recruited. German princes in particular were grateful to be able to get rid of their surplus troops for good pay.

Sultan Mehmet IV and his advisors also took the opportunity to decimate unreliable palace troops and janissaries who had deposed and murdered Sultan Ibrahim (“the madman”) and his grand vizier in 1648 .

Small war 1648 to 1666

Very soon the island was mostly occupied by the Ottomans, but the heavily fortified Candia fortress held out. The Ottomans began the siege on May 1, 1648. Venice was able to intercept the Ottoman supplies with its fleet, blocked the Dardanelles , won several naval battles against the Ottoman fleet in 1651 near Naxos and in 1656 off the Dardanelles and was still able to supply Candia well. The following two decades were marked by endless guerrilla warfare on land and sea. If Venice was able to maintain the supply situation and capture Turkish ships, the Turks were pushed back. In winter, when the battle was still and the Mediterranean was impassable because of the winter storms, there was no supply for Candia. If the Turks got through with their ships, the siege would continue on Crete. The plague broke out in Candia again and again , and so the grueling guerrilla warfare led to high losses of people and material on both sides.

Attack on Candia

In the spring of 1666, the Turks began a major attack on Candia, which had now been expanded into a huge fortress. As the commander of the land troops on Crete, the Swiss Hans Rudolf Werdmüller led the defensive battles. Candia was protected by seven forts and associated trenches , counter-barges , a labyrinth of covered paths , underground tunnels and countless entrenchments , bastions , ramparts , casemates , capons , hornworks and ravelins . Most of the facilities were connected to one another underground. The works were built using hollow structures made of air bricks, wood and earth. That was new to the engineers who had come from Central Europe; They were used to earthworks or walls with heaped earth behind them, but not to hollow structures and only got to know the resistance of such coverings here.

Fortress builders and engineers from many countries learned their craft under the leadership of the Huguenot St. André. With this knowledge of the organization, technology and logistics involved in building a fortress, the German engineer Georg Rimpler was supposed to make a significant contribution to the perseverance of the city of Vienna during the Second Turkish Siege of Vienna in 1683 . He and Johann Bernhard Scheither († after 1677) wrote down their experiences in important works on the art of siege over the next few years. After his departure, he criticized it sharply: "The Venetians would have put more on the tiller than on the shovel."

The Ottomans began to storm the fortress, but lost nearly 20,000 men by the fall. An army of slaves and diggers dug trenches and mine tunnels. The struggle shifted underground.

The mine war

A mine war on this scale had never existed before, and it remained unique until the First World War . Thousands of Candia residents and galley slaves dug deeper and deeper into the earth. In the city, tunnels were dug for listening posts, counter mines and corridors to cut off outposts . The miners had a lot of problems to deal with. The air supply for the working and fighting troops had to be ensured, otherwise they threatened to suffocate from mine gas or from CO 2 oversaturation; For this purpose, oversized forged bellows were used, with which the air was distributed through a pipe system into the tunnel. Penetrating groundwater was extracted with pipes and pumps. Orientation was carried out using a compass.

The attackers blew themselves through entire wall sections and bastions with 50–170 tons of powder . With counter mines one tried to dig, blow up or put the mines under water. If possible, attempts were made to clear out the enemy powder before the detonation or to divert the explosion pressure through a nearby counter tunnel. In the most heavily besieged sections there was a multi-story system of corridors, casemates, galleries, tunnels and mines. When two opposing tunnels came into contact, bitter fighting ensued underground. The miners suffocated in blown tunnels, were buried, crushed, burned or drowned.

Struggles

Numerous new killing devices have also been tried and used above ground. Various bombs, hand grenades, terrain mines, explosive boxes, incendiary and explosive barrels were developed or improved. The Turkish respondents often came within pistol range of the shot and blown positions. Snipers were deployed and the besieged attempted to destroy individual batteries and tunnel entrances with surprising assault attacks. Sandbags cost half a thaler, and the fighting tried to take away the sandbags they had captured.

The mercenaries vegetated in holes in the ground and in ruins. Hunger was problematic in times of poor supply through Venice. The wages were reduced to a fraction of their value by inflation , and the necessary food could no longer be paid for. Soon scurvy , plague and other epidemics broke out. Anyone who was sick or injured had little chance of survival. Defectors were the order of the day, but the Turkish supply situation was no better. The Swiss Michael Cramer, son of a citizen of Lindau , recruited as a mercenary and later sold to Venice together with his troops, describes gruesome details: “We were given the weapon at the battlefield. Now we had the choice to fight or to run over to the Ottomans, and they were no better there. "

The food supply was inadequate and expensive. They helped themselves with the preparation of rats and mice and evidently also ate human meat, so that this had to be forbidden under the death penalty. The fat left out by the fallen was used as "Turkish lard" to rub on the feet. Straps could be cut from the skin and taken home as a souvenir. Germans, French, Italians, Savoyards , Swiss and Maltese were brought into the fortress and disappeared into its ruins. When a colonel was buried, often only a dozen mercenaries marched behind the ten company flags; it even happened that a man had to carry several flags.

End of the siege

The end came in August 1669. The Turks had rebuilt their fleet and thus disrupted the supply of Candia. The French withdrew first after their leader, Grand Admiral Beaufort , died in a nightly sortie on June 25th. A little later they were followed by the Maltese. Soon the miners and mercenaries mutinied in the trenches and ramparts. They threatened to kill their officers if they did not surrender immediately. On August 25th, Jul. / 4th September 1669 greg. the armistice was signed. The defenders were given free withdrawal and were allowed to take all material with them. On their way back, the Christians fell victim to a plague epidemic, some ships sank and pirate attacks cost many more lives.

In the last three years of the siege there have been over 60 assaults, 90 failures, 5,000 mine explosions and 45 major underground skirmishes; 30,000 Christians and 120,000 Turks had fallen.

output

Venice lost Crete, many Aegean islands and bases in Dalmatia to the Turks. The old trade republic had lost its supremacy in the Mediterranean.

literature

- Roberto Vaccher: L'esercito Veneziano e la difesa di Candia 1664-1669: il costo di una vittoria mancata , tesi di laurea, Università Ca 'Foscari, Venice 2015 ( online ).

- Wilhelm Kohlhaas: Candia 1645–1669. The tragedy of an occidental defense with the aftermath of Athens 1687 . Biblio-Verlag, Osnabrück 1978, ISBN 3-7648-1058-0 , ( studies on military history, military science and conflict research 12).

Individual evidence

- ^ History of Venice

- ↑ "Anjetzo they [the Janissaries] are no longer in such great esteem when ... 1648 deposed the Kayser Ibrahm, and ... strangled. But after the time the Grand Veziers, in order to preserve their principals as well as their own esteem, have to humiliate them by sacrificing the most daring of them at the siege of Candia "; Johann Heinrich Zedler: Large complete universal lexicon. Vol. 14, Leipzig / Halle 1735. Sp. 200–203 sv Janissaries, Janissaries Aga.

- ↑ From the life story of Georg Rimpler ( Memento from January 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 849 kB) p. 171

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Matschke: The cross and the half moon. The history of the Turkish wars , p. 368.

- ↑ From the life story of Georg Rimpler ( Memento from January 11, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 849 kB) p. 170