Avalanche disaster on December 13, 1916

1915

1st Isonzo - 2nd Isonzo - 3rd Isonzo - 4th Isonzo - Lavarone (1915-1916)

1916

5th Isonzo - South Tyrol offensive - 6th Isonzo - Doberdò - 7. Isonzo - 8. Isonzo - 9th Isonzo -

First Dolomites Offensive - Second Dolomites offensive -

Avalanche disaster

1917

10th Isonzo - Ortigara - 11th Isonzo - 12th Isonzo - Pozzuolo - Monte Grappa

1918

Piave - San Matteo - Vittorio Veneto

In the avalanche disaster of December 13, 1916 , several thousand soldiers died as a result of dozens of avalanches during the mountain war in the First World War in the Southern Alps ( Trentino-South Tyrol ) . Climate researchers and historians from the University of Bern reviewed the events in 2016 and, in summary, classed them as one of the worst weather-related disasters in Europe.

Martial starting position

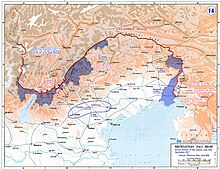

The armies of Austria-Hungary and the Kingdom of Italy fought bitterly against each other in the Southern Alps during the First World War. The front of the mountain war ran between 1915 and 1917 from the Stilfser Joch on the Swiss border via the Ortler and Adamello to northern Lake Garda . East of the Adige then over the Pasubio and on to the seven municipalities .

Thousands of soldiers on both sides holed up in positions in the high mountains. The soldiers faced particular dangers from the forces of nature . On some sections of the front, more soldiers were killed by avalanches , rockfalls and accidents than by enemy fire.

Meteorological starting position

In December 1916, snow fell almost continuously in the Southern Alps for nine days. The trigger was a "blocked" atmospheric circulation , the so-called "Negative East Atlantic / West Russia Pattern" (a high pressure ridge over western Russia and a low pressure area over western Europe). In the southern Alps, it often leads to heavy precipitation and unusually high temperatures in the Mediterranean area. The water temperature of the Mediterranean also rises due to the circulation pattern. This in turn is the main source of water vapor for the southern Alps. In the winter of 1916/17, two to three times the amount of snow recorded between 1931 and 1960 was measured.

December 13, 1916

On December 13, 1916, after nine days of snowfall, the snowpack on the Alpine war front reached critical weight. A change in the weather also led warm and humid air masses from the Mediterranean region to the southern Alps and caused the snow line to rise rapidly. It also began to rain at higher altitudes. The white masses grew thicker and heavier. As a result, dozens of huge avalanches fell across the region, including in places that had previously been considered safe. Entire companies were buried. According to the latest estimates, up to 5,000 soldiers fell victim to the avalanches that day. The first battalion of Kaiserschützen Regiment No. III, for example, had 230 deaths that day and on the Marmolada , the highest mountain in the Dolomites , a single avalanche killed between 270 and 332 men. In recent years, the melting glaciers released bodies and finds.

The catastrophic avalanches of December 13, 1916 are today considered to be one of the most devastating known storm events in European history. Despite its scale, the catastrophe remained largely unknown, not least for reasons of military secrecy. Although December 13, 1916 fell on a Wednesday, for unknown reasons, especially in publications from the Anglo-Saxon region, the catastrophe is called "White Friday". In Italy, following the incident on December 13, Lucia celebration , however the "Black Lucia Festival" (in this context, La Santa Lucia Nera spoken).

Scientific processing

On the 100th anniversary of the catastrophe, climatologists and historians from the University of Bern reconstructed the extreme weather at the time. Due to the historical documents and diaries of contemporary witnesses as well as the few existing measurement data, the events in individual cases were already well documented and traceable. However, it had to be checked whether the contemporary witnesses perceived this correctly or whether they had exaggerated it when reporting into the valley. The researchers examined the causes and effects of those terrible avalanches using climate reconstruction and historical analyzes. Based on these investigations, they found that the soldiers had by no means exaggerated in describing the events. The commanders on site correctly assessed the danger for their troops and sometimes tried to order a withdrawal, which they were not always allowed to do. The officers in the valley could not really imagine the situation from a safe distance and did not always grant these requests to withdraw.

The knowledge about the events of 1916 can also contribute to the analysis of current and future extreme meteorological situations.

literature

- Y. Brugnara, S. Brönnimann, M. Zamuriano, J. Schild, C. Rohr, D. Segesser: December 1916: White Death in the First World War. (= Geographica Bernensia. G91). Bern 2016, ISBN 978-3-905835-48-9 . doi: 10.4480 / GB2016.G91.02

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stefan Reis Schweizer: A War in Ice and Snow In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of January 17, 2018

- ↑ Alois Feusi: Avalanche drama from 1916 in the Southeast Alps: The day on which avalanches tore thousands of soldiers to their death In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung of December 12, 2016

- ↑ How the greatest avalanche disaster in World War I came about In: Salzburger Nachrichten of December 13, 2016

- ↑ Dipl.-Ing. Rudolf Schmid: The summit book of the Punta di Penia (MARMOLATA) on www.dolomitenfreunde.at

- ^ The Black Festival of Santa Lucia at Adamello in 1916 in Italian , accessed on February 17, 2017.