Isonzo battles

| date | May 23, 1915 to October 27, 1917 |

|---|---|

| place | Along the Isonzo Valley |

| output | Victory of the Central Powers |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| losses | |

|

approx. 645,000 |

approx. 450,000 |

1915

1st Isonzo - 2nd Isonzo - 3rd Isonzo - 4th Isonzo - Lavarone (1915-1916)

1916

5th Isonzo - South Tyrol offensive - 6th Isonzo - Doberdò - 7. Isonzo - 8. Isonzo - 9th Isonzo -

First Dolomites Offensive - Second Dolomites offensive -

Avalanche disaster

1917

10th Isonzo - Ortigara - 11th Isonzo - 12th Isonzo - Pozzuolo - Monte Grappa

1918

Piave - San Matteo - Vittorio Veneto

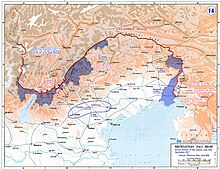

The Isonzo battles were twelve major combat operations in the First World War between the Kingdom of Italy and the two allied Central Powers Austria-Hungary and the German Empire . With over a million soldiers killed, wounded and missing, the Isonzo battles were among the most costly battles of the First World War. They were named after the river Isonzo ( Slovene Soča ), around whose valley the fronts stretched. Most of the area is in present-day Slovenia . The fighting in the Julian Alps on the upper reaches of the Isonzo were also part of the 1915–1918 Mountain War . While the first eleven Isonzo battles were characterized by Italian offensives that brought no decision despite great losses on both sides, in the last battle the Austrian troops, now reinforced by German units, counterattacked and successfully pushed back the Italian army.

Italy enters the war

On May 23, 1915, the previously neutral Italy Austria-Hungary declared war, with which it had been allied with the German Reich since 1882 ( Triple Alliance ; emerged from the dual alliance concluded in 1879 between the German Empire and Austria-Hungary). The treaty committed the signatories to mutual assistance in the event of a simultaneous attack by two other powers or an unprovoked French attack on Germany or Italy. After the secret London Treaty had been signed in London on April 26, 1915, Italy canceled the Triple Alliance Treaty , only to join the First World War a little later on the Entente side . The Triple Entente was very keen to build an additional front against the Central Powers , which is why they included almost all of Italy's territorial demands in the treaty, which mainly included the Italian-speaking areas of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian army was inadequately prepared for this case, as no major defensive measures had been taken at the border with Italy in order to “not irritate” the potential opponent in advance (as the Austro-Hungarian High Command reads ).

The Italian chief of staff, General Cadorna , ordered his troops to quickly advance into Austrian territory after the declaration of war. At the lower Isonzo the Italian 3rd Army ( Duke of Aosta ) was held up by the weak kuk forces for two days until they could finally fight their way to the river on May 25th between Pieris and Gradisca . In the neighboring section, too, the leaders of the Italian 2nd Army (General Frugoni ) reached the west bank of the Isonzo between Monte Sabatino and the village of Selz on the same day. The Austro-Hungarian Lieutenant Colonel Richard Körner ordered his heavy artillery brigade to start fighting the attackers immediately. In doing so, he saved the Gorizia bridgehead, although there was a contrary order from the command of the Southwest Front , thus creating the conditions for the construction of the Isonzo front .

Even before the First Isonzo Battle, the entire k. u. k. Navy to bombard the Italian east coast between Venice and Barletta . The Italian fleet was surprised at Venice, so that they hardly resisted and the Austro-Hungarian Navy was able to end its attacks without losses.

The battles

As commander in chief of the Austro-Hungarian Isonzo defense was General of Infantry Svetozar Boroević determined that on May 27, from the eastern front coming in Ljubljana had arrived, as Chief of Staff of the 5th Army was FML Aurel von le Beau called. By the evening of May 27, only 32 battalions and 9 batteries had arrived in the combat area on the Isonzo. Due to the different layout of the terrain, four defensive sections were set up on May 28th.

Section I : XV. Corps under General of the Infantry Vinzenz Fox between Krn and Tolmein .

- 1st division: FML Stephan Bogat (Tolmein)

- 50th Division: FML Franz Kalser von Maasfeld

Section II : XVI. Corps under Feldzeugmeister Wenzel Wurm on the Isonzo line from Auzza to Wippach .

- 18th Division: GM Eduard Böltz (Auzza-Plava)

- 58th Division: GM Erwin Zeidler (Gorizia)

Section III : Goiginger group from Wippach to Parenzo.

- 57th Division: FML Heinrich Goiginger (Doberdò plateau)

- 93rd Division: GM Adolf von Boog (between Krn and Wippach)

- 94th Division: FML Hugo Kuczera (coastline to Parenzo)

Section IV : Fiume Coastal Pale under Major General Karl Marić, from Monte Maggiore to the Croatian-Dalmatian border.

Preliminary fights

The Italian 3rd Army continued the VII. And XI. Corps against the Doberdò plateau. In the 2nd Army, the VI. Corps to attack Gorizia, while the II Corps carried out a mock attack against Monte Sabotino in order to divert from the planned main attack on the Kuk , for which the river at Plava had to be bridged first. On June 6th, the XI. Corps Gradisca, but failed at Sagrado at the planned river crossing. The arrival of the kuk 48th Division (FML Theodor Gabriel) on June 10 stabilized the front until the middle of the month. While Cadorna already had 214 battalions, 40 squadrons and 118 batteries, the Austro-Hungarian 5th Army was only able to oppose the enemy with 36 battalions, 16 squadrons and 75 batteries. Between June 12 and 16, the Italian II Corps managed to cross the Isonzo at Plava. Cadorna's strategic goal for the next battle remained the breakthrough to Trieste .

First battle of the Isonzo, June 23 to July 7, 1915

The focus of the Italians was directed against the Monte San Michele, the heights in the east and north of Monfalcone and around the bridgehead of Gorizia. Oslavija and the Podgora heights could not be taken, and the Italians had to withdraw again from Plava. The area in front of Sdraussina, which the Austrians had already given up, remained in Italian hands. Attacks against Selz and Doberdò failed. After several attacks, the Italian 14th Division managed to take the place Redipuglia. Repeated attacks north of it at Polazzo were so decisively repulsed that the Italians did not undertake any further attacks. Only at Sagrado was the edge of the plateau climbed and to the south of it the edge of the karst area was reached.

Second Battle of the Isonzo, July 17 to August 3, 1915

The Italians failed to make the breakthrough in the second battle either. Neither the front arch between Monte San Michele and Seiz nor the Görzer bridgehead or that at Tolmein could be depressed. General Cadorna was able to show only minor gains in land that were out of proportion to the losses incurred.

Third Battle of the Isonzo, October 18 to November 4, 1915

The efforts of the Italian 3rd Army, again with a focus on the Gorizia bridgehead, the northern part of the Doberdò plateau and against Zagora, were nowhere crowned with success. The attacks between Flitsch and Plava, carried out simultaneously by the Italian 2nd Army from October 21st to 24th on the upper reaches of the Isonzo, also collapsed with heavy losses. On the Italian side, the casualties are given as 62,466 dead, wounded, missing and prisoners. The Austro-Hungarian troops suffered losses of around 40,000 in this third battle.

Fourth Battle of the Isonzo, November 10th to December 14th, 1915

Until November 15, the focus of the renewed Italian attacks was on the northern plateau of Doberdò, between November 18 and 22 their attempts to break through were concentrated at Oslavija. Thereafter, unsuccessful attempts were made to wear down the Austro-Hungarian armed forces by attacking the entire Isonzo front. In the first four Isonzo battles alone, the Italians lost a total of around 175,000 men. The Austrian losses amounted to around 123,000 soldiers.

Fifth Battle of the Isonzo, 11. – 16. March 1916

The fifth Italian offensive was one of the shortest battles of the Isonzo, which was only carried out at the request of the Entente . France and Great Britain wanted to relieve their soldiers in the Battle of Verdun . General Cadorna left the action in this battle entirely to the commanders of the Italian 2nd and 3rd Armies.

The troop strength of the Italians was 286 battalions and 1,360 guns , plus 90 battalions in reserve , Austria-Hungary had 100 battalions and 470 guns, plus 30 battalions in reserve (again 3: 1). The aim of the Italians was again to conquer the high plateau of Doberdò and the city of Gorizia. The offensive was canceled without gaining ground.

Due to the shortness of the battle and the rather half-hearted approach of Italy, the losses were low, both sides lost about 2,000 men.

Sixth Isonzo Battle, 4th-15th centuries August 1916

On August 4th, the Italian VI. Corps with the attack against the front arch of Gorizia, which was held by the reinforced kuk 58th Division (FML Zeidler ) with 18 battalions. In lighter terrain south of Monte Sabatino, it was possible to push in the bridgehead in its northern part and to reach the eastern bank of the river with strong forces. Since Monte San Michele flanked the Gorizia bridgehead, it was imperative for the Italians to take this too. The section was defended by the kuk VII Corps (17th and 20th divisions). At the same time as the attack on the bridgehead and Monte Sabotino, the battle for Monte San Michele began. Between August 9 and 11, the Gorizia front arch and the positions on Monte San Micheles had to be evacuated by the Austrians step by step. Further Italian attacks on Monte Santo were unsuccessful. Extremely loss-making battles took place on the plateau of Comen, as there were no prepared positions for the defenders and these had to be laboriously created in the rocky floor of the Karst.

Seventh Battle of the Isonzo, 14.-18. September 1916

After a long barrage, the Italians attacked on September 14, 1916 at a width of about 20 kilometers south of the Wippach . On September 16, heavy attacks were again directed against the northern part of the Karst height, but all of them collapsed with great losses. The great losses suffered by the attackers meant that they could no longer carry out an intensive attack in the area north of Gorizia near Plava. The combat activity, which in any case barely exceeded the normal level, became significantly weaker. On the basis of this assessment of the situation, Colonel General Boroević relocated his few reserves to the area south of Gorizia, where on September 17 and 18, 1916 there were again massive Italian attacks, all of which, however, were successfully repulsed.

Eighth Battle of the Isonzo, 9.-12. October 1916

The eighth Isonzo battle was a direct continuation of the seventh. The Italians' target, Trieste, was the same. In addition, a diversionary attack was made between the Wippach and St. Peter near Gorizia. However, the Italians only managed to conquer a few trenches east of Gorizia, and to achieve a minimal gain in land at Hudi log and Kostanjevica .

The Italian losses amounted to about 24,000 men, Austria-Hungary lost 25,000 men.

Ninth Battle of the Isonzo, October 31 to November 4, 1916

The aim of the Italian attacks was again the breakthrough in the direction of Trieste, where they carried out diversionary attacks in the Gorizia area. After 5 days of artillery bombardment, the Italian army launched an attack. This time they tried to force the breakthrough with an enormous concentration of troops (8 divisions on a front width of only 8.5 km). The Italians actually achieved the breakthrough at Mount Volkovnjak (Kote 284) and the temporary conquest of the Fajti Hrib hill as well as the advance to Kostanjevica and the encirclement of the village of Hudi Log. Boroević's army was now on the verge of collapse, but again the Italian army did not pursue it energetically enough and hesitated too long after the successes it had already achieved. So Boroević could the 5th k. u. k. Gather the army again, undertake a counterattack, retake the village of Hudi Log and even repel the Italians over the Fajti Hrib hill. The front line after this battle ran from Fajti Hrib via Kostanjevica and Korita to the Timavo River .

The fighting took the lives of around 16,000 Italians and 11,000 Austrians.

Tenth Battle of the Isonzo, May 12 to June 5, 1917

In the tenth battle Italy deployed 450 battalions and 4,000 guns, Austria-Hungary 210 battalions and 1,400 guns and mortars.

The aim of the Italian offensive was again to break through to Trieste. After two and a half days of barrage along the entire front section from Tolmein to the Adriatic Sea and a diversionary attack near Gorizia, the main attack took place south of Gorizia. The Italians managed to temporarily conquer the village of Jamiano , but were thrown back from the heights of Hermada after an Austrian counterattack. Between Monte Santo and Zagora, north of Gorizia, they succeeded in crossing the Isonzo, building a bridgehead and defending it.

The losses were higher than in the previous battles, Italy lost 160,000 men, including around 36,000 dead, Austria-Hungary 125,000 men (17,000 dead). The Italian army captured 23,000 Austrian soldiers and the Austrian army took 27,000 Italian prisoners, which shows the weak morale at the time.

Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo, August 17 to September 12, 1917

Despite the rather unfavorable situation for the Entente due to the defeat of Romania and the de facto departure of Russia , Italy was nevertheless able to set up the largest armed force to date. The aim of this offensive was to cut through the Austrian supply connections and to conquer Trieste. The Italian army was successful, but failed because of the goals set, as in the battles before.

The Italian 2nd Army managed to cross the Isonzo in several places and to conquer the high plateau Bainsizza, while the attacks of the Italian 3rd Army on the Hermada hill failed despite the gain in terrain. Again, the Italian troops did not pursue consequently, so that the Austrian Commander-in-Chief Boroević was able to collect and dig his troops in the second line of defense. The new front line ran in the territory of the Italian 2nd Army after the battle on the line: Monte Santo (Kote 682) - Vodice (Kote 652) - Kobilek (Kote 627) - Jelenik (Kote 788) - Levpa. And in the section of the 3rd Italian Army on the line: Log - Hoje - Zagorje - San Gabriele.

The fighting was fierce. The central corner of the Austro-Hungarian defense was the Monte San Gabriele . Heavy fighting broke out around this mountain with its almost 1500 meter long front line, because with the loss of Monte San Gabriele the way to the Wippach valley , to Adelsberg and also to Trieste would have been open to the Italian troops . The Austrian approach routes to Monte San Gabriele were already under constant Italian gunfire and were partly shrouded in a cloud of dust and poison gas. Due to the fighting, the mountain itself was a single unrecognizable waterless pile of stones and rubble, criss-crossed with caverns , rock caves and shot-up trenches. Since the dead and wounded could often not be recovered, a sweet smell of decay spread everywhere and all the surrounding wells and springs were poisoned. The summit was repeatedly assaulted by around 100 Italian battalions (more than 80,000 men) and was incessantly under fire from mortars, gas grenades and artillery. At night, fireworks and Italian headlights illuminated the front and access routes. Despite the greatest effort, the use of elite soldiers such as the Arditi and almost uninterrupted barrage, the Italians did not succeed in the complete conquest. At the time of the heaviest fighting (mid-August 1917 to September 12, 1917), 25,000 soldiers died on Monte San Gabriele on the Italian side and 15,000 on the Habsburg side. There are no precise figures on the number of wounded, prisoners and sick people.

The losses of the Italian army amounted to approx. 150,000 men (the figures vary greatly, including approx. 30,000 dead), Austria-Hungary lost 100,000 men (the figures also vary greatly, including approx. 20,000 dead). In addition, both armies were weakened by rampant diseases ( dysentery , typhus ), so that up to 500,000 men on both sides were sidelined due to illness. However, these failures are not included in the loss figures.

Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, 24.-27. October 1917

The twelfth and final battle of the Isonzo was very different from the others. After the heavy losses in the Tenth and Eleventh Battles of Isonzo, the Austro-Hungarian High Command was faced with the question of waiting for the next attack and, if the defenses were insufficient, risking military defeat, or risking a counterattack. The offensive was chosen and the Italians were surprised. After the German Supreme Army Command had promised strong troop aid, October 24, 1917 was set as the day of the attack. In this twelfth battle of the Isonzo, the army of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy , supported by the 14th German Army , succeeded in forcing a breakthrough on the Isonzo Front between Flitsch and Tolmein , among other things due to the massive use of poison gas by the German pioneers . During the offensive, for example, the German pioneer units used gas cannons with 70,000 green and blue cross grenades containing the substances chlorinated arsenic and diphosgene , new on the southern front , against which the Italian gas masks were ineffective. This victory also resulted in the collapse of the still intact Italian fronts in the Fiemme Valley and the Dolomites as well as in the Julian and Carnic Alps . The Italian 2nd, 3rd and 4th Army and the Carnic Group (Zona Carnica) were forced to retreat from Friuli into the Venetian lowlands. The losses of the Italians in this battle amounted to around 40,000 dead and wounded, 298,745 prisoners, 3,512 artillery pieces, 1,732 mortars, 2,899 machine guns and other war material.

At the beginning of November 1917, the advance of the Central Powers finally got stuck on the floodplain of the Piave . The Italian army was able to stabilize itself here with the last few efforts; this was also due to the slowly increasing troop support from England, France and the USA.

General

The battles on the Isonzo hardly differed, apart from the twelfth and last. Artillery preparation for days in a confined space, attacks by the infantry , sometimes bitter battles up to close range , counterattacks. Neither side achieved larger gains in the first eleven battles. Even in the high mountains , the battle was no less violent, despite the unsuitable terrain. It happened several times that engineer units dug tunnels under a summit which was occupied by enemy soldiers; the tunnels were then filled with explosives and the entire mountain peak along with the enemy garrison was blown up (e.g. the Col di Lana in Buchenstein). Nature did the rest. In the war winter of 1916/17, more soldiers died from avalanches than from direct enemy weapons. However, both sides helped by using artillery fire to trigger avalanches over the enemy positions.

Traces of the theater of war can still be seen today. Numerous caverns , bunkers and supply shafts that were blasted into the rock by the soldiers have been preserved. Some of the defensive structures at that time were restored as objects to be seen, so the structures at the small Pal and the Cellon are particularly worth seeing. At the Cellon, the Austrian supply route could also be viewed by the Italians and attacked with artillery, which is why Austrian pioneer units built a supply shaft in the mountain, the so-called Cellon tunnel, which climbs almost vertically and is provided with wooden stairs. Some of today's via ferratas, hiking trails or roads were used during the war. a. also built by Russian prisoners of war. Because of the favorable conservation conditions in the karst fighting area, there are places where bones, rusted belt buckles, bayonets, barbed wire and the like can still be found today. Among other things, the Krn mountain is a few meters lower today than it was before the fighting because its summit was shot and blown away by artillery and engineer attacks.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers called some areas of the Death Hill or Death Mountain. Italian soldiers called the Monte Santo Santo Maledetto (damned saint) and sang u. a. a song with the text "O Monte Nero ... traitors of my youth".

According to the historian MacGregor Knox's estimate, the Habsburg losses were much smaller than the Italians. Statistically, in 1915 and 1916 there were 2.2 Italian soldiers for every Austrian soldier who fell; in 1917 the ratio was 1 to 10; the mean for the whole war was 1 in 4.3.

The Isonzo battles were not decisive for Italy's war. Rather, the decisive Italian victory (at least from an Italian perspective) is the Battle of Vittorio Veneto , the third and last of the Piave battles following the Isonzo battles shortly before the end of the war, which led to the armistice at Villa Giusti . This battle as well as the experience at the front and the huge losses nourished the Italian myth of the “lost victory” in the post-war period. The dissatisfaction of broad sections of the population was sparked primarily by the fact that the Kingdom of Italy was not granted all the hoped-for areas in Dalmatia in the Paris suburb agreements after the First World War . A circumstance which, in addition to the failure of the Italian general strike in 1922 ( also called "Caporetto of Italian Socialism" by Mussolini in allusion to the Battle of Good Freit), paved the way for the victory of fascism and the takeover of power by Benito Mussolini .

See also

literature

- Stefan Kurz: The 7cm mountain cannon M.99 No. 169 of the Army History Museum. An "Ortler gun" on the Isonzo. In: Viribus Unitis. Annual report 2018 of the Army History Museum. Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-902551-85-6 , pp. 33–55.

- Mark Thompson, "The White War": Life and Death on the Italian Front, 1915-1919. Faber & Faber, London 2008, ISBN 978-0-571-22333-6 .

- Vasja Klavora: Blue Cross. The Isonzo Front Flitsch / Bovec 1915–1917. Hermagoras / Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt 1993, ISBN 3-85013-287-0 .

- Miro Šimčić: The battles on the Isonzo. 888 days of war in the Karst in photos, maps and reports. Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 2003, ISBN 3-7020-0947-7 .

- Ingomar Pust : The stone front. On the trail of the mountain war in the Julian Alps - from the Isonzo to the Piave. Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 2005, ISBN 3-7020-1095-5 .

- Alexis Mehtidis: Italian and Austro-Hungarian Military Aviation On the Italian Front In World War I. General Data, 2., ext. Edition 2008, ISBN 978-0-9776072-4-2 (1st edition 2004).

- Marija Jurić Pahor: The memory of war. The isonzo front in the memorial literature of soldiers and civilians. Hermagoras / Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt 2017.

- Review by Erwin Köstler : The memory of the war. In: Zwischenwelt . 35, 3, November 2018, ISSN 1606-4321 p. 68 f.

filming

Web links

- isonzofront.de

- berg.heim.at

- kobariski-muzej.si (English)

- Maps of the Isonzo battles

- Weekly news reports (videos) about the Isonzo battles on the European Film Gateway

- Wording of the contract with German History in Documents and Images (DGDB) . **

- The war events 1917-18

- Gas war during the First World War

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ingomar Pust: Die Steinerne Front, On the trail of the mountain war in the Julian Alps - from Isonzo to Piave , Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz 2005, p. 12 f.

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's last war. Volume II, p. 537.

- ↑ Austria-Hungary's last war. Volume III., Vienna 1932, p. 394 f

- ↑ Miro Simcic: The battles on the Isonzo 888 days of war in the Karst in photos, maps and reports . Leopold Stocker Verlag, Kranj-Slovenia 2003, ISBN 3-7020-0947-7 , p. 248 .

- ↑ Vasja Klavora: Monte San Gabriele. The Isonzo Front 1917. Hermagoras-Mohorjeva, Klagenfurt / Vienna 1998, ISBN 3-85013-578-0 , p.?.

- ↑ Fortunato Minniti in: Labanca, Übergger (ed.): War in the Alps. 2015, p. 102 with reference to MacGregor Knox, Una riflessione sistemica sulle forze in campo, 1917–1918, in: Berti and Del Negro (eds.): Al di qua e al di la del Piave. P. 30 f.