Bosnian annexation crisis

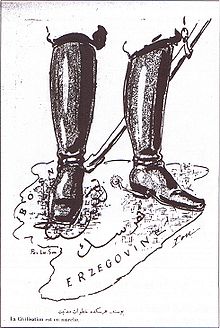

The Bosnian annexation crisis or simply the Bosnian crisis is the term used to describe the crisis that followed the annexation by Austria-Hungary of the areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina that had previously belonged to the Ottoman Empire under international law .

prehistory

As early as 1683, the power of the Ottoman sultan was waning . Initially, this was due to the efforts of Austria and Russia to expand their territory at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, with Prince Eugen's victories over the Turks playing a crucial role. Later, the peoples' aspirations for independence came on the European territory of the Turkish Empire. The Ottoman Empire was able to maintain its European territories in the 19th century because Austria and Russia did not agree on their division and their influence on the successor states. The policy of the other European powers, for example in the Crimean War , which tried to thwart the Russian endeavors towards the strategically important straits, the Bosporus and the Dardanelles , also contributed to this.

In 1878, after the Russo-Ottoman War, in the preliminary peace of San Stefano , the Ottoman Empire was to forego most of its European territories. This increase in power in favor of Russia called the other European powers on the scene. During the Berlin Congress , to the displeasure of Russia, large parts of the European territory of the Ottoman Empire were divided up. This benefited the principalities of Serbia and Montenegro , which gained full independence, but also the Ottoman Empire itself, which was able to keep a large part of its European provinces. Bosnia and Herzegovina also formally remained with the Ottoman Empire, but according to the Budapest Treaty of 1877 and Art. 25 of the Berlin Peace of July 13, 1878, they were placed under Austro-Hungarian administration, which was exercised by the joint Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Finance . The Sanjak Novi Pazar , located between Serbia and Montenegro , which was of great strategic importance in terms of military strategy, was to remain with the Ottoman Empire. However, Austria received the right to station troops there and to own military and trade routes.

From July 29, 1878, Austria-Hungary began to occupy these areas , which led to bloody clashes with the population in many places. In the sanjak of Novi Pazar, the cities of Priboj , Prijepolje and Bijelo Polje were also occupied.

On October 3, 1903, Austria and Russia adopted the Mürzsteg Protocols , with which they agreed to ensure peace and quiet in the Balkans.

Annexation decision

On September 16, 1908, the Austrian Foreign Minister agreed Alois Lexa Freiherr von Aehrenthal and Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky on Castle Buchlau in Moravia that Austria Bosnia and Herzegovina could acquire, Russia in return the consent of Austria-Hungary with the free passage of Russian warships through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles should receive.

The year 1908 seemed a fitting time for Austria-Hungary to annex the two provinces, as the Ottoman Empire was politically weakened after the revolution of the Young Turks , but also appeared to be an interesting alternative for Bosnia-Herzegovina because of its promise of internal reform , especially since the administration contract with the Ottoman Empire expired after 30 years, i.e. in 1908. This weakness and insecurity gave rise to action for other Balkan states as well: Crete unilaterally proclaimed its annexation to Greece , Bulgaria , which was under the suzerainty of Turkey, declared itself fully sovereign, and its prince Ferdinand I assumed the title of tsar .

In the Young Turkish Revolution , officers forced the reintroduction of the 1876 constitution in the Ottoman Empire on July 24, 1908. As a result, parliamentary elections were to take place there, including in the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which formally still belonged to the Ottoman Empire, but had been administered, built up and modernized by Austria in the thirty years after 1878. Austria responded with the official annexation, which was a clear violation of the Berlin Treaty of 1878. On the occasion of his name day on October 4th, Franz Joseph I , who had ruled since 1848, issued a handwriting “to extend the rights of my sovereignty to Bosnia and Herzegovina and to put the order of succession valid for my house into effect for these countries as well, as well as to make them constitutional Facilities ". This decision was implemented on October 5, 1908.

The annexation was directed not only against the Ottoman Empire, but also against Serbia, which tried to unite all southern Slavs in one state ( panserbism ). Since 1906, there has also been a sharp tariff conflict between the two countries , the so-called pig war .

During the crisis in 1908, Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf suggested several times that Serbia should be conquered as well. Montenegro should also be eliminated or at least experience a “narrowing”. The southern Slavs were to form a complex within the framework of the monarchy and subordinate to the Habsburg Empire , like Bavaria to the German Empire. At that time he also strove to win Albania , western Macedonia and Montenegro, with the strategic goal of establishing Saloniki as an Austrian bastion on the Aegean Sea . His imperialist goal was the unification of all western and southern Slavs under Austrian rule, which he justified with the missionary idea of strengthening Christian culture. These plans were rejected by Foreign Minister Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal .

Political Impact

The annexation led to furious protests in the Ottoman Empire, in Serbia and in Russia, where Pan-Slavist currents were widespread. The free passage through the Dardanelles, which the tsarist empire was granted in return, failed due to the opposition of the British. Therefore, for the second time since the Berlin Congress, Russia felt betrayed. For several weeks there was an acute danger of war, as the United Kingdom and Russia threatened to restore the Ottoman Empire to its old legal position, to the disadvantage of Austria.

The Ottoman Empire itself reacted with a trade boycott against Austrian goods, which seriously damaged Austrian trade in this region. The loss of legitimacy of the Young Turkish government, which had to be accused of having revealed more in its short term of office than Sultan Abdülhamid II in the decades of his sole rule, was so great that conservative forces with the incident of March 31 (according to the Gregorian calendar: dated April 13, 1909 tried to end the second Ottoman constitutional period . Their uprising was bloodily suppressed.

The fact that there was no war was ultimately due to the military imbalance between the two alliance and Russia, which was weakened by the lost war against Japan . France , which had been allied with Russia since 1894 , saw the alliance case as not given. The German Reich , on the other hand, stood unconditionally behind its partner - Reich Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow spoke in front of the Reichstag on March 29, 1909 for the first time of " loyalty to the Nibelungs " in German-Austrian relations - and thus forced Russia to give in.

The annexation brought Austria-Hungary more disadvantages than advantages, which aroused outrage in the Vienna Imperial Council . At first it was unclear whether Transleithanien or Cisleithanien should get sovereignty over Bosnia and Herzegovina. The annexation threatened the fragile internal balance of power. The Hungarian government claimed the new provinces because Bosnia was temporarily part of the areas of the St. Stephen's Crown in the Middle Ages . But Croatian nationalists also saw their chance. They demanded that Bosnia should become the semi-autonomous Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia , which, according to their ideas, should then be released from Hungarian hegemony and raised to the third state of the Danube Monarchy, with the addition of Dalmatia . This would have turned the dualistic state construction established in the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 into a trialism . Ultimately, it was decided that Bosnia and Herzegovina should be administered jointly by both halves of the empire and thus de jure (as it was in fact before) should become, to a certain extent, direct to the empire.

With the annexation, Austria-Hungary also had the burden of defending the area against any attack from outside and against internal unrest. Both cases were by no means improbable in 1908 because of Russian and Serbian interests on the one hand, and the attitude of the Bosnian Serbs towards Austria-Hungary on the other. In addition, the k. u. k. Monarchy over Bosnia and Herzegovina was founded solely on a legal title that initially nobody in Europe recognized - in complete contrast to the European-wide guaranteed legal status of the empire in the provinces before the annexation. The Habsburg Empire therefore ran the risk of being left without the help of allies in the event of an attack on Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Domestically and economically, Austria-Hungary was weakened by the annexation. These were bitterly poor provinces in which there was little to be gained economically. The economic boycott and the mobilization of the armies of the Austro-Hungarian state, however, put a considerable strain on the economy.

As a result of the acute danger of war in the course of the annexation crisis, nationalists of all shades - not just the southern Slavs - saw the chance of implementing their nation-state ideas approaching, while the German Austrians complained about the further Slavization of Austria-Hungary. In Vienna , Prague , Ljubljana and other cities of the monarchy, these national upheavals led to numerous riots, especially at the universities. From Prague these unrest spread to numerous other Bohemian and Moravian cities, where Germans and Czechs violently attacked each other. In Prague it went so far that a state of emergency had to be imposed. The annexation had created great internal political unrest and the nationalism of the peoples had become more aggressive instead of weaker.

In terms of foreign policy, the annexation of Bosnia put a heavy strain on relations with the Kingdom of Italy , which was allied in the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany and saw its interests in the Balkans threatened.

Resolving the crisis

Due to the unexpectedly strong resistance, not least from the Ottoman Empire, the government in Vienna soon showed itself ready to give in. In the negotiations Austria-Hungary held out the prospect of advocating the lifting of the capitulations , unequal trade agreements that had been a burden on the Ottoman Empire since the 16th century. On February 26, 1909, both states agreed that the Austrians should pay 50 million crowns and withdraw their troops completely from the Sanjak Novi Pazar. The Ottoman Empire then recognized the annexation.

Although a European war could still be avoided, the annexation crisis is to be seen as an important step on the way to the First World War . A great war for the Balkans was in sight. The first of the two " Balkan Wars " (against the Ottoman Empire) broke out in 1912, although not yet with the direct participation of the great powers. The peace in Europe had finally become a “prewar”. It also showed how much Austria-Hungary was dependent on the German Reich in most relations.

literature

- Karl Adam: Britain's Balkan Dilemma. British Balkan Policy from the Bosnian Crisis to the Balkan Wars 1908–1913. Hamburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8300-4741-4 .

- Holger Afflerbach : The Triple Alliance. European great power and alliance politics before the First World War. Vienna et al. 2002, ISBN 3-205-99399-3 .

- Jürgen Angelow: Calculus and prestige. The dual alliance on the eve of the First World War. Cologne et al. 2000, ISBN 3-412-03300-6 .

- Jost Dülffler, Martin Kröger, Rolf-Harald Wippich: Avoided Wars. De-escalation of conflicts between the great powers between the Crimean War and the First World War 1865–1914. Munich 1997, ISBN 3-486-56276-2 .

- Horst Haselsteiner: Bosnia-Hercegovina. Orient crisis and south Slavic question. Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-205-98376-9 .

- Noel Malcolm: History of Bosnia. Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-10-029202-2 .

- Helmut Rumpler : An opportunity for Central Europe. Civil emancipation and state collapse in the Habsburg monarchy. (= Austrian History 1804–1914 ), Vienna 1997, ISBN 3-8000-3619-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Stephan Verosta: Theory and Reality of Alliances. Heinrich Lammasch, Karl Renner and the Dual Alliance (1897–1914) . Europa-Verlag, Vienna 1971, ISBN 3-203-50387-6 , p. 76.

- ↑ Holger Afflerbach : The Triple Alliance. European great power and alliance politics before the First World War. Böhlau, Vienna 2002, ISBN 978-3-20599399-5 , p. 628.

-

↑ Josef Matuz : The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, p. 251 f.

Christopher Clark : The sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. From the English by Norbert Juraschitz, 2nd edition, DVA, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 70 of the Engl. Output. - ↑ Agilolf Keßelring (ed.): Guide to history. Bosnia-Herzegovina , 2nd edition, Paderborn 2007, ISBN 978-3-506-76428-7 , p. 37.

- ^ Gerhard Zimmer: Violent territorial changes and their legitimation under international law. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-428-02568-7 , p. 117.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, p. 252.

-

↑ Field Marshal Conrad: From my service 1906–1918 . Volume 1: The time of the annexation crisis 1906–1909 . Vienna / Berlin / Leipzig / Munich 1921, p. 59, 537 and 615.

Heinz Angermeier : The Austrian imperialism of Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf . In: Dieter Albrecht (Ed.): Festschrift for Max Spindler on his 75th birthday . Munich 1969, p. 784. - ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, p. 252 f.

- ↑ Klaus Hildebrand : German Foreign Policy 1871-1918 . Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, p. 36.

- ^ Josip Frank : The integration of Bosnia and Herzegovina . In: Alfred von Berger et al. (Ed.): Österreichische Rundschau . Volume XVII, October – December 1908. Fromme, Vienna / Leipzig 1908, ZDB -ID 528560-4 , pp. 160–163. - online .

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1985, p. 252.