Battle of Tannenberg (1914)

| date | August 26th to August 30th, 1914 |

|---|---|

| place | At Allenstein |

| output | German victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

| approx. 153,000 men including: 8th Army : 6 line divisions 3 reserve div. 3 Landwehr Div. 1 cavalry division. 728 guns 296 machine guns |

approx. 191,000 men including: 2nd Army : 9 1/2 infantry divisions 3 cavalry divisions 612 artillery pieces 384 machine guns |

| losses | |

|

3,436 dead |

approx. 30,000 dead and wounded |

Eastern Front (1914-1918)

1914

East Prussian operation ( Stallupönen , Gumbinnen , Tannenberg , Masurian Lakes ) - Galicia ( Kraśnik , Komarów , Gnila Lipa , Lemberg ,

Rawa Ruska ) - Przemyśl - Vistula - Krakow - Łódź - Limanowa - Lapanow - Carpathians

1915

Humin - Mazury - Zwinin - Przasnysz - Gorlice-Tarnów - Bug Offensive - Narew Offensive - Great Retreat - Novogeorgiewsk - Rovno - Swenziany Offensive

1916

Lake Narach - Brusilov offensive - Baranovichi offensive

1917

Aa - Kerensky offensive ( Zborów ) - Tarnopol offensive - Riga - Albion company

1918

Operation Punch

The Battle of Tannenberg was a battle of the First World War and took place in the area south of Allenstein in East Prussia from August 26 to August 30, 1914 between German and Russian armies. The German side fielded 153,000 men and the Russian side 191,000 soldiers. It ended with a victory for the German troops and the defeat of the Russian forces that had invaded southern East Prussia.

Initially referred to as the “Battle of Allenstein” in the German media, it was renamed the Battle of Tannenberg a short time later at the request of Paul von Hindenburg for propaganda purposes . In fact, the village of Tannenberg (today Stębark ) is not in the main combat area, but Hohenstein . The naming was intended to outshine the defeat of the Knights of the Teutonic Order against the Polish-Lithuanian Union in 1410 , known in German historiography as the Battle of Tannenberg .

Strategic prerequisites

East Prussia was strategically particularly vulnerable due to its geographical location as a head start in Russian territory . Given Russia's poor infrastructure, the Schlieffen Plan assumed that France and Russia would simultaneously declare war on the assumption that France could mobilize four weeks faster. Therefore, the entire army should first be deployed against France. The German Supreme Command stationed seven armies on the Western Front in order to bring about a quick victory against France . However, due to the July crisis , which Russia had already used to mobilize, the situation was exactly the opposite. The province was only defended by the 8th Army and was therefore particularly endangered because of the low number of troops. The Russian headquarters had already taken this into account in its pre-war planning. To relieve its western allies, the Russian high command sent two armies against East Prussia. The 1st Army (Nyemen Army) under Paul von Rennenkampff advanced from the east, the 2nd Army (Narew Army) under Alexander Samsonow penetrated from the south into East Prussia.

During the first few days of the operation, this strategy seemed to work. The Russian 1st Army advanced on East Prussian territory and scored a first break-in after the Battle of Gumbinnen on August 19th. The Russian General Staff expected that the Germans, who had only one army available in East Prussia, would retreat across the Vistula. This assessment initially seemed to be true: The Commander-in-Chief of the 8th Army, Colonel General von Prittwitz , was unsettled and signaled the army command in Koblenz that the army was withdrawing behind the Vistula. Although this corresponded to the directives for action, Chief of Staff von Moltke believed that Prittwitz was no longer up to the situation.

On the night of August 22nd, he was suddenly and unexpectedly put on hold for his entire staff . He was to be followed by the retired Infantry General Paul von Hindenburg with Major General Erich Ludendorff as Chief of Staff . Ludendorff, who had already distinguished himself on the western front during the conquest of Liège , was immediately taken in a motor vehicle from the Namur area to the headquarters in Koblenz , where he arrived around 6 p.m. A special train, which Hindenburg boarded in Hanover , took him eastwards. The next noon the generals reached their destination Marienburg .

For both generals, evacuation of the original Prussian province without a fight was out of the question. The Russian high command, unaware of this change, assumed that East Prussia would be evacuated after the German troops had broken off the battle of Gumbinnen . The 1st Army was marched with the aim of Königsberg to bind the 8th Army. The 2nd Army should relocate the enemy bound in this way and "fall in the back". Thus, both large associations moved spatially separated from each other and could hardly give each other support. Another reason for the spatial separation of the 1st Army from the 2nd Army was that the impassable Masurian Lake District lay between their areas of operation .

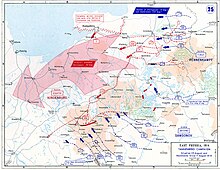

Two-sided deployment

At this point in time, the Russian 2nd (Narew) Army had already penetrated a width of 60 kilometers up to the Soldau - Neidenburg - Ortelsburg line in southern East Prussia. As an eastern flank protection the VI. Army corps under General of the Infantry Blagoweschensky (4th and 16th Divisions) with the 4th Cavalry Division advances to Ortelsburg. As western flank protection consisting of the 1st Corps with assignments and two cavalry divisions from Usdau to Soldau. The western middle combat group consisting of the XV. Army corps under Lieutenant General Klujew (6th and 8th Division) and an additional division fought from Lippau to Orlau and the eastern middle combat group consisted of the XIII. Army corps under General Martos Infantry (1st and 36th Divisions) stood west of Jedwabno . General von Ludendorff followed Max Hoffmann's plan of attack, which had already been worked out , and which provided for fighting the two Russian armies one after the other. This should compensate for the numerical superiority of the Russians. Hoffmann's plan envisaged first attacking the Russian 2nd Army under General Alexander Samsonov , which was invading from the south . The choice to attack this army first and not the Russian 1st Army was made with the intention of being able to retreat - to the west - across the Vistula in the event of its own defeat by the German 8th Army. This was only guaranteed if the combat area was not too far to the east.

Even before Hindenburg took over command, the 1st Army Corps under General Hermann von François von Gumbinnen had been moved by rail to the south west of the advance axis of the Russian 2nd Army. After being informed of the opponent's positions and orders by aerial reconnaissance and listening to unencrypted Russian radio messages, General von Ludendorff also initiated a general disengagement of the rest of the army. The Russian 1st Army was to be observed in the Insterburg area to Lötzen through a small "curtain" of several Landwehr brigades and the 1st Cavalry Division and prevented from continuing their operations. The XVII. Army Corps under August von Mackensen and the I. Reserve Corps under Otto von Below began to break away from their sector and marched against the right flank of the Russian 2nd Army, which was operating in the direction of Allenstein .

The German project was made easier by a miscalculation by the Russian commanders. General Rennkampff reacted only three days after the start of the German regrouping initiated on August 23 by resuming his own attack operations, which pointed in the direction of Konigsberg . The front commander of the superior Russian Northwest Front, General Jakow Schilinski , also interpreted the German behavior completely wrongly at this point: In the firm belief that the German units would withdraw before the pressure of the 1st Army on Königsberg, he did not exercise any caution. He did not consider that the German troops could turn against the southern 2nd Russian Army.

During these events, Samsonov's army had already completed its tenth day of marching, as on the orders of the front staff, for security reasons, the troops had already been unloaded from the railway wagons deep in their own hinterland and had to march the rest of the way on foot. However, only the central parts (XIII., XV. And XXIII. Corps) and the right wing (VI. Corps) of the army moved on German territory. On the left wing, the I. Corps was held back at the border on orders from Schilinski to cover the flank. Furthermore, the commander in chief urged a quick advance by the 2nd Army, which completely separated the center and its western flank. Thus, the planned flank protection became the isolation of a quarter of the Russian armed forces.

Since August 22nd, the right wing of the German 8th Army, the XX. Army Corps under General von Scholtz Artillery , before the overwhelming strength of the Russian XIII. and XV. Corps returned to the northwest via the Usdau- Neidenburg line . On the evening of August 23rd, the 37th Division between Lahna and Orlau started fighting with the Russian vanguard. On the left wing was the XX. Corps, the 3rd Reserve Division of the General von Morgen was sent to reinforce it, and it was advancing from Allenstein via Hohenstein. On the following day Scholtz was instructed to hold his new position between Gilgenburg and Tannenberg defensively until the advance of the I. Reserve Corps and the XVII. Army Corps would be effective in the rear of the enemy. On the right wing of the German 8th Army, the 1st Army Corps of General François positioned itself last after the long rail transport via Deutsch-Eylau , without the reconnaissance of the opposing Russian 1st Corps noticing.

Course of the battle

On August 26th the attack of the German I. Army Corps began, General von François was to take Seeben and Usdau. The XX. Army Corps should support the attack with its right wing. General von Scholtz ordered the 41st Division under Major General Sontag to attack the Ganshorn - Groß Gardienen line , with the 37th Division to the left to take part in the attack. The first Division under Lieutenant General von Conta reached at about 8.00 Tautschken, the 2nd Division under Lieutenant-General of Falk was around 10:00 am in front of large Koschlau . In the evening the 2nd Division lay east of Grallau, the 1st Division on the Meischlitz - Groß-Grieben line. General von François did not allow another attack on Usdau to be carried out that day. He justified his hesitation with the fact that his artillery had not yet come close enough to the starting positions and that he could not have justified an attack ordered too early. As a result, the Russian troops in the center - ignorant of the danger that threatened their left wing - advanced further and further inland in accordance with the orders of the front staff.

General Samsonov ordered the attack from his center - XV. and XXIII. Corps under Generals Kluev and Kondratovich - on Neidenburg. The 1st Corps under General Artamonov was to cover its own left flank at Mława . The Russian XIII. Corps under General Martos swung to Allenstein and occupied this town without a fight.

Against the northward moving German troops should the VI. Corps under General Blagoveschensky advance to Passenheim, here events had already rolled over. The Russian VI. Corps, the easternmost unit of the 2nd Russian Army, had advanced furthest north in the Bischofsburg area . However, under Samsonov's orders, it only had to cover the advance of the central units, and Blagoveshchensky was not prepared to face a stronger enemy. Now he was alone between Lautern and Groß-Bössau facing two German corps - the von Mackensen ( 35th and 36th Divisions ) and Belows ( 1st and 36th Reserve Divisions ), which came from the northeast after the withdrawal from Gumbinnen intervened in battle. The two German troop leaders succeeded in exploiting their local superiority by two to one and in the battle on Lake Bössau on August 26th to force the Russian corps into a disorderly retreat.

On August 27, General François resumed the attack on Usdau after receiving a personal visit from Ludendorff . The left wing of the I. Army Corps was formed by the 2nd Division, which attacked Usdau from the south-west. The right wing was taken over by the 1st Division, which encountered Usdau from the west and north-west. Another detachment under Lieutenant General von Schmettau was to support the attack from Bergling. Thanks to its material superiority, the 1st Army Corps broke through the positions of the unprepared 1st Russian Corps, which then retreated in a southerly direction. The 1st Division pushed up to the border at Soldau by evening . The 2nd Division reached Neidenburg and initiated the encirclement of the enemy center from the south.

Ludendorff himself was surprised by the quick success of the right wing of his attack front. He immediately recognized the possibility of encircling the Russian 2nd Army, but he urged consolidation because the middle parts of Samsonov's unit were already exerting strong pressure on the defensive positions of the corps (Scholtz) near Allenstein and there was therefore a risk that the German lines in the Center could be broken. The I. Reserve Corps was therefore swiveled to the right in order, together with the 1st Landwehr Division Goltz near Allenstein, to establish a connection with the heavily struggling center. In addition, the General's 3rd Reserve Division, advancing on the left wing of the Scholtz Corps, attacked from Morgen to the east in order, together with the 37th Division under Lieutenant General von Staabs , to defeat the mass of the Russian XIII. and XV. Corps to be held at Hohenstein . At the same time, the right wing of the XX. Army Corps with the 41st Division, initiated the retreat of the Russian XV by an attack near Waplitz . Corps to cut off at Neidenburg, but suffered heavy losses.

Only Mackensen's corps (XVII.) Now continued to drive the eastern enclosure in the area west of Ortelsburg to the south. The left wing under General von François also received an order from Ludendorff to stop its advance and also to cede troops to the central sector. However, the subordinate commander refused this order and ignored it without comment.

On August 28th, parts of the 1st Division (Schmettow Cavalry Division) west of Willenberg with the advance guard of the 35th Division of the XVII. Unite Corps. The Russian 2nd Army, which was supposed to cut off the assumed retreat of the Germans, was thereby itself enclosed.

The Russians were thus cut off from supplies, and the news that German units were blocking the route of retreat spread like wildfire among the Tsar's men. The confusion created by this shock was due to the fact that the remaining units were scattered in the basin during the fighting and Samsonov was unable to establish contact with his troops. Smaller units attempted to break out spontaneously, so that 10,000 men could escape through the thin line of German forces, but the bulk of the army surrendered, disorganized and demoralized. Many soldiers felt that they had been betrayed by their commanders.

On August 30th, however, a report was received by both the AOK and General François that the 1st Russian Army Corps was marching north from Mława and was about 6 km from Neidenburg to relieve the trapped army. Although the Army High Command put all available troops on the march, they would not have arrived until August 31. The situation was mastered by General François. South of Neidenburg, he threw all available soldiers (Schlimm and von Mühlmann) head-on at the enemy without giving up the enclosure in the north. The Russian relief troops then went back. The Russian commander, General Samsonov committed suicide on the same day in this desperate situation suicide . The place is still marked today by the Samsonow stone .

Reasons for the Russian failure

Bad planning before the war

Replenishment

The level of supplies and the logistics of the troops at the beginning of the war represented a serious handicap to the Russian combat strength. The tsarist military had mobilized smoothly according to the plans of its officers, but the other preparations were inadequate. Miscalculations arose in the provision of field hospitals and food. However, the technical equipment was appropriate for its time.

artillery

The artillery was also weakened by another strategic mistake. The officer corps of the artillery saw the main task of heavy artillery in the defense of fortresses that lay across the border. The field army, on the other hand, received little heavy artillery. Mobile heavy guns had a higher firepower than their lighter counterparts, but did not have a noticeably greater range. Above all, there was a lack of proper agreement between the sub-units.

cavalry

A tactical misjudgment that was to accompany the Russian army through the first year of the war was the assessment of the cavalry. Russian generals still considered them the classic offensive weapon. However, with machine guns and repeating weapons that could fire precisely up to 800 m away, the defensive power of the infantry was already far superior to the attack by riders. The cavalry divisions were of little use except in their reconnaissance role, but they used up large resources. 4,000 men of a cavalry division with their horses needed about the same space as a 12,000-man infantry division for a rail transport. A horse needed at least 3 kg of grain per day. As a result, valuable supply resources were used for a now ineffective type of weapon.

Strategic mistakes made by senior commanders

After the catastrophic outcome of the battle, the responsible front staff under General Schilinski tried to shift as much guilt as possible on the dead Samsonov. However, these allegations do not stand up to closer examination. Even before he reached the border with the German Reich, the commander of the 2nd Army received contradicting and nonsensical orders from his direct superior. This was, for example, the aforementioned unloading of the troops in front of the terminal stations. Some battalions marched more than 50 km along railroad tracks before they even came near the border. As a rest day was also later refused, this led to the soldiers becoming prematurely tired.

The army was also weakened by the fact that troops were continuously withdrawn from it. Under political pressure from allied France, another offensive was planned at the headquarters , which was to take the shortest route to Berlin via Silesia . The 9th Army was set up in western Poland for this operation . In order to form this, a total of 5 divisions and 400 guns were withdrawn from the 2nd Army. This loss would have severely weakened the combat strength alone, but these units were not withdrawn as planned, but were gradually released from the formation. Other units in turn were assigned, which made it difficult for the commander to keep track of his own forces at all.

Even when the fighting had started, Schilinski interfered with various orders in Samsonov's area of competence, for example by prohibiting the I. Corps from being drawn closer to the main force. His constant insistence on a further advance of the central corps also contributed to the encirclement of the army.

Another factor that contributed to the Russian defeat was the personal antipathy between Generals Samsonow and Rennenkampff: Both had been divisional commanders in the Russo-Japanese War and were deployed on adjacent sections of the front. After a heavy defeat, the two generals met by chance at the train station in Mukden and accused each other of lacking support. Finally there was a fight between the two of them; a subsequent duel could only be prevented by a direct order from the tsar. The German military secret service was informed of the hostility of the two generals and assured the leadership that it was extremely unlikely that Rennenkampff's First Army would support Samsonov's troops in a critical situation.

"If the Battle of Waterloo was won on the Eton pitch , then the Battle of Tannenberg was won on a platform in Mukden."

Army staff error

Samsonov himself found himself in a precarious situation even without contact with the enemy, but instead of turning the tide, he himself made the situation worse. His army owned 42 aircraft , but most of them were not operational. Samsonow neglected to use this capacity and to push for it. While his German opponents were already carrying out regular aerial reconnaissance, the Russian general still seemed to be completely indifferent to this option. Another means of enemy detection was the cavalry, but it was held back by the army staff and should be saved for offensive operations. Thus the 2nd Army marched blind to East Prussia without any enemy reconnaissance, without realizing the trap.

In general, the leadership style of the Russian army chief took little account of the speed of a modern war with its new demands. Samsonov had his headquarters right on the border until the last few days and was thus 24 hours away from his own army. That was how long it took to get a message from the front to his location and back to the troops. As a result, he was unable to react quickly enough to any changes in the situation. In addition, Samsonow only issued individual daily orders , which was not conducive to coordination.

Tactical and technical errors

An even more critical weak point in the operations at Tannenberg, however, was of a purely technical nature. The Russian army was equipped with radio equipment, but the use of encryption methods was not yet practiced. While the German troops only radioed in encrypted form, their opponents more often did so in plain text. One of these radio messages, which was overheard by German radio operators, contained the entire marching instructions for an army. After Ludendorff verified this information through airplanes, he was in possession of an immense operational advantage.

Evaluation of the German leadership

The statements on the tactical performance of the German leadership are different. Irregularities such as Hermann von François' refusal to give orders and Kurt von Morgen's arbitrariness played into the hands of German operations . However, this does not mean that this battle unjustifiably occupies its important place in the history of war. This was less because of their impact on the war than because of the tactical performance of the German leadership. The idea of the Battle of Cannae , which is known as the “mother of the encircling battle ”, has never been so “flawlessly” realized since then as through the progressive and unconventional army leadership by Ludendorff in East Prussia.

In particular, however, the progressive German aerial and radio reconnaissance should be mentioned, which reported every movement of the Russian armies to the German leadership. However, it is a legend that the operation plan was drafted by Ludendorff alone on the train ride from the western front, without the usual view of the terrain. In fact, besides Erich Ludendorff, it was mainly his close colleague Max Hoffmann who worked out the plan . The basic strategic concept for the relocation of troops and the attack had already been played through in maneuvers in advance, Ludendorff and Hoffmann achieved the practical implementation in the specific case. But Ludendorff, as demonstrated by his unhappy work during the Weimar period , was aggressive, impulsive and often a victim of his nerves. As an experienced officer, the calm and sovereign Hindenburg managed to balance out the actual planner of the operation at Tannenberg. His charisma also had a positive effect on the fighting morale of the imperial troops. The Hindenburg / Ludendorff tandem was exemplary for military cooperation and formed the counterpart to the disorganized Russian leadership.

Ultimately, the combination of own achievements and the failures of the Russian commanders enabled the battle to be conducted with a tactical advantage. So the Germans led a battle of attack near Tannenberg and a battle of delay near Allenstein and thus used their forces optimally. On the other hand, the Russians were forced to take the defensive despite their initial initiative due to inadequate education, poor organization and poor coordination. As a result, the tsar's troops were never given the level of preparation for combat as their opponents.

consequences

The battle was the German army's first major victory in World War I. Tannenberg experienced a propagandistic exaggeration during the empire , which still shapes the image of the battle today. Although the victory in East Prussia was a necessary and surprising liberation strike by the imperial army, the Russian military power was only temporarily weakened by its defeat. The tsarist empire was able to cope with the losses of around 30,000 fallen and wounded and around 95,000 prisoners due to its large population. His peace army alone consisted of about two million men even without mobilization. Without further decisive successes, it would only have been a matter of time before the Russian army had re-positioned forces against German territory. An attack by Russia had been repulsed at Tannenberg, but with its reserves the tsarist empire remained a threatening enemy on Germany's eastern flank.

Furthermore, the threat to East Prussia was not completely averted by the success, but only mitigated, since the 1st Army under Paul von Rennenkampff was still at its limits. It was only defeated in the following battle of the Masurian Lakes , for which freedom of action had now been given. The psychological impact on Russia was rather marginal, as the population firmly believed in a victory through targeted propaganda by the ruling house and political parties until 1917. Likewise, there were no conceivable positive effects on the Russian leadership, for example in the form of the dismissal of incompetent commanders at army and corps level. The military personnel, especially Schilinski, succeeded in shifting the blame on to the dead commander-in-chief of the 2nd Army, who could no longer defend himself.

As a further consequence, the Tannenberg memorial was erected in 1924–1927 near Hohenstein ( Olsztynek in Polish ).

Most of the dead were buried in mass graves on the battlefield. But even then, military cemeteries were deliberately established. After the war, many of the smaller graves were closed. Some have survived to this day and, like all 550 cemeteries of the First World War, are under Polish monument protection and are financially and organizationally supported by the Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge . The cemeteries of honor are:

- Frankenau cemetery of honor

- Lahna Cemetery of Honor

- Logdau cemetery of honor

- Mills of honor cemetery

- Orlau Memorial Cemetery

- Oschekau cemetery of honor

- Great Gardienen Memorial Cemetery

- Scottau Cemetery of Honor

- Waplitz Cemetery of Honor

The actual strength of the 8th Army in the period from August 21 to 31, 1914 was 246,088 soldiers. According to the information in the "Medical Report on the German Army", the following losses occurred during the same period, which are based on the ten-day reports from the individual units:

- Sick: 4,316 soldiers

- Wounded: 7,461 soldiers

- Fallen: 1,726 soldiers

- Missing: 4,686 soldiers

Since some of the wounded died and it can be assumed that the greater part of the missing had also fallen, the total number of deaths is higher than 1,726, but below 10,000.

Name and location

The battle took place in the area south of Allenstein in East Prussia. It was an encompassing battle that ultimately involved a wide territory. The center of this area was in Hohenstein . Strictly speaking, it should therefore be called the Battle of Hohenstein. The imperial congratulatory telegram initially referred to the battle as the Battle of Allenstein.

The battle was only subsequently renamed the Battle of Tannenberg at the request of Hindenburg. In German there was already a so-called battle near Tannenberg . This took place in 1410 between the villages of Grünstelde , Tannenberg and Ludwigsdorf . It had ended with a decisive defeat for the Teutonic Order and had become a national myth in divided Poland as the Battle of Grunwald in the 19th century , which helped to preserve Polish cultural identity during the times of the Russification and Germanization policies of the partitioning powers. By naming the victorious battle of 1914, Hindenburg wanted to symbolically have wiped out the "Scharte von 1410". The name is not wrong, because Tannenberg was included in the battlefield and only about 14 km from Hohenstein. This designation has also been adopted in all other languages. The authorship of this designation was claimed by Ludendorff and Hoffmann. Hoffmann claimed that Ludendorff originally wanted to call the battle the Battle of Frögenau .

Battle locations:

- Bössauer See

- Frankenau

- Frögenau

- Hohenstein

- Lahna

- Neidenburg

- Orlau

- Usdau see also: Battle of Usdau

- Seeben

- Soldau

- Waplitz see also Battle of Waplitz

- Willenberg

Evaluation of the battle in literature

- The Russian author and Nobel Prize winner for literature Alexander Solzhenitsyn processed the battle in the first part of August 1914 of his trilogy The Red Wheel as a novel . The novel largely refers to historical sources on both sides. Solzhenitsyn also brought in the experience of his father, who had fought in East Prussia, and other combatants. Solzhenitsyn emphasizes in his novel the rigid hierarchy of the Russian army and the inability of the senior officers to modernize it. His main character, a colonel in the Russian army, tragically fails in his attempt to encourage change in his superiors. As decisive for the outcome of the battle, Solzhenitsyn portrays the arbitrariness of General Hermann von François and assigns Hindenburg and Ludendorff a smaller share in the victory of the German army at Tannenberg.

- For Winston Churchill , too , Hermann von François was the hero of Tannenberg: "the glory of Tannenberg must go to François forever". He saw in François' behavior the way one wins battles the wrong way, while his superiors threatened to lose the battle the right way. In particular, Churchill calls his approach to Usdau a rare combination of caution and daring. However, this assessment should be treated with caution. Replacing François with Churchill and Tannenberg with Gallipoli , the result is less a historical analysis than an autobiographical utterance influenced by wishful thinking.

literature

- John Keegan : The First World War. A European tragedy. Rowohlt Verlag , Reinbek near Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-499-61194-5 .

- Markus Pöhlmann : Death in Masuria: Tannenberg, 23rd to 31st August 1914 . In: Stig Förster, Markus Pöhlmann and Dierk Walter (eds.): Battles of world history. From Salamis to Sinai. CH Beck , Munich ³2002, pp. 279-293. ISBN 978-3-406-48097-3 .

- Dennis E. Showalter : Tannenberg. Clash of empires, 1914 . Brassey's, Washington 2004, ISBN 1-57488-781-5 .

- Norman Stone : The Eastern Front 1914-1917. Penguin Books Ltd., London 1998, ISBN 0-14-026725-5 .

- Barbara Tuchman : August 1914 . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag , Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-15395-6 .

- Christian Zentner : The First World War. Data, facts, comments. Moewig , Rastatt 2000, ISBN 3-8118-1652-7 .

Movie

- East Prussia and its Hindenburg . Movie , D 1917, directed by Gustav Trautschold / Richard Schott .

- People in need. A hero song by Tannenberg . Movie , D 1925, Director: Wolfgang Neff .

- Tannenberg . Feature film , D 1932, director: Heinz Paul .

- Hindenburg vs. Grand Duke Nicholas . Documentary , USA 2002, director: Jonathan Martin, 13th episode of the documentary series Clash of Warriors .

- The Tannenberg myth . Documentary , D 2004, directed by Susanne Stenner, 1st episode from the documentary series The First World War .

Web links

- Battle of Tannenberg at the LeMO

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Christian Zentner: The First World War , Rastatt 2000 p. 108.

-

^ Frithjof Benjamin Schenk : Tannenberg / Grunwald. In: Etienne François , Hagen Schulze (ed.): German places of memory . Volume 1, Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-59141-8 , pp. 438-454.

Jesko von Hoegen: The hero of Tannenberg. Genesis and function of the Hindenburg myth (1914–1934). Böhlau, Cologne / Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-17006-6 , pp. 40f. - ^ Norman Stone: The Eastern Front 1914-1917 , London 1998, pp. 44-48.

- ^ Siegfried Schindelmeiser: The outbreak of the world war , in: Corps Baltia , vol. 2, p. 64. Munich 2010.

- ^ Norman Stone : The Eastern Front 1914-1917. , London 1998, pp. 59-61.

- ^ Reichsarchiv Volume II: The Liberation of East Prussia , Mittler und Sohn, Berlin 1925 p. 114 f.

- ^ A b c d e f Norman Stone: The Eastern Front 1914–1917. London 1998, pp. 61-67.

- ^ Reichsarchiv Volume II. The Liberation of East Prussia , Mittler und Sohn, Berlin 1925, p. 126 f.

- ^ A b Norman Stone: The Eastern Front 1914-1917. London 1998, pp. 69-51.

- ^ Erik Durschmied : Hinge Factor. How Chance and Stupidity have changed History . Hodder & Stoughton, London 1999 ISBN 0-340-72830-2 p. 200 ff.

- ↑ Geoffrey Regan: Military Duds and Their Greatest Battles. Komet Verlag, Cologne, 2003 ISBN 3-89836-538-7 p. 75.

- ^ Dennis E. Showalter : Tannenberg. Clash of empires, 1914. Brassey's, Washington 2004, ISBN 1-57488-781-5 , p. 329.

- ^ John Lee: The Warlords: Hindenburg and Ludendorff. London 2005, ISBN 0-297-84675-2 , p. 53.

- ^ Medical report on the German army in the world wars 1914/1918, III. Volume, Berlin 1934, p. 36.

- ↑ Note: Both Erich Ludendorff and his First General Staff Officer Max Hoffman later claimed to have had the idea of renaming. (Hartmut Boockmann: German History in Eastern Europe - East Prussia and West Prussia, Siedler Verlag, 2002, p. 54.)

- ↑ Note: “At my suggestion, the battle was called the Battle of Tannenberg, as a reminder of the battle in which the Teutonic Knights were defeated by the unified Lithuanian and Polish armies. Will the German ever again allow Lithuanians, and especially Poles, to benefit from our powerlessness and rape us? Should centuries-old German culture be lost? ” (Erich Ludendorff in Meine Kriegserinnerungen , 1919, p. 44).

- ↑ Holger Afflerbach (edit.): Kaiser Wilhelm II. As supreme warlord in the First World War. Sources from the military environment of the emperor 1914–1918. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57581-3 , p. 148.

- ↑ Christoph Mick: "To the forefathers to fame - to the brothers to encouragement". Variations on the theme of Grunwald / Tannenberg. In: zeitenblicke 3 (2004), No. 1 (PDF; 534 kB).

- ^ Feliks Szyszko: The Impact of History on Polish Art in the Twentieth Century. ( Memento from September 26, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Karl Friedrich Nowak: The records of Major General Max Hoffmann Verlag für Kulturpolitik, Berlin 1929, p. XX.

- ↑ Erich Pruck: Solshenitsyns "August 1914". Seen militarily. Eastern Europe , No. 3, 1972, pp. 215-219.

- ^ Winston S. Churchill: The Unknown War - The Eastern Front , London, 1931, pp. 213-214.

- ^ Dennis E. Showalter: Tannenberg: clash of empires. 1914. Dulles, 2004, p. 330.