July crisis

chronology

|

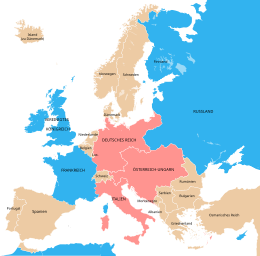

The July crisis was the worsening of the conflict between the five major European powers and Serbia , which followed the assassination of the Austrian heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914 and led to the First World War . To this day, the motives and actions of all the powers involved, politicians and diplomats, are controversial both in public and among historians.

For example, the respective answer to the war guilt question depends crucially on how the events during the July crisis are assessed, with the assessment questions also making certain psychological-sociological aspects of "playing va-banque" important, such as the so-called " brinkmanship ".

Consequences of the Sarajevo attack

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were shot dead by the Bosnian Serb youth Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914 during an official visit to the Bosnian capital Sarajevo . Princip comes from the Bosnian Krajina and was a member of the nationalist youth movement Mlada Bosna . He and his co-conspirators were quickly caught.

In Vienna, Foreign Minister Count Berchtold suspected that the perpetrators of the double murder were in Belgrade:

“It is clear from the testimony and confessions of the criminal perpetrators of the June 28th attack that the Sarajevo murder was hatched in Belgrade, that the murderers received the weapons and bombs they were equipped with from Serbian officers and officials belonged to the Narodna Odbrana , and that ultimately the transport of criminals and their weapons to Bosnia was organized and carried out by senior Serbian border organs. "

Two names could also be identified: that of the Serbian officer Vojislav Tankosić , who had already been involved in the murder of the Serbian king Aleksandar Obrenović , and that of a Bosnian named Milan Ciganović who was employed by the Serbian railroad. From this, the Australian historian suspects Christopher Clark that he was an undercover agent of the Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić within the conspiratorial Serbian officer organization Black Hand was. In 1914, however, nothing was known about the existence and involvement of the Black Hand . Instead, the Narodna Odbrana was seen as the mastermind behind the assassination attempt. However, there was clarity about the motive of the assassins and their possible backers: They wanted to weaken Austria-Hungary and thus achieve a long-term connection between occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia.

The Serbian government was held to be morally complicit in letting organizations like the Narodna Odbrana have their way . The chief investigator in Sarajewo, Section Councilor Friedrich Wiesner , wrote in his report of July 13, 1914 to the imperial and royal (kuk) Foreign Ministry a. a .:

“The Serbian government was also involved in the conduct of the assassination attempt or its preparation and provision of weapons by nothing proven or even suspected. Rather, there are indications that this is to be regarded as excluded. By testimony of the accused, it was established that the assassination attempt in Belgrade was decided and prepared with the assistance of Serbian state officials Ciganović 'and Major Tankošic', both of whom provided bombs, Brownings, ammunition and cyanide. "

Individual passages of this telegram, sent in two parts, were cited as evidence that Austria had only used the attack as a pretext for an ultimatum. After the war u. a. Wiesner argued that the Serbian government was complicit and told the historian Bernadotte Everly Smith that his report was "largely misunderstood":

“Personally, from the evidence gathered during the investigation, he was convinced that the Serbian government was morally complicit in the Sarajevo crime, but because the evidence was not of such a quality that it would have stood the test of time , he was not ready to use it in a real trial against Serbia. He made that clear when he returned to Vienna. "

This representation contradicts Wiesner's own minutes of the discussions from July 4 to 8, 1914 in the commission in the kuk Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding the consequences of the assassination attempt, which show that Wiesner urged moderation and conscientious investigation of the facts, but did not listen has been. The fact that the other commissioners did not understand that the material available did not allow any clear conclusions to be drawn about Serbia's complicity plunged him into a state of depression. Just to prevent worse things from happening, he accepted the assignment to write a first draft of the demands on Serbia, to which he noted: “The only directive I get is that the demands should not be too easy to meet. On the other hand, I declare that I can only conceptualize them in such a way that they are sharp and strict but not impossible to achieve, that they cannot be interpreted by Europe as interfering with the sovereignty of Serbia ”. Wiesner's design was then changed in this direction.

The Serbian government was aware that there was a risk that the Austro-Hungarian government would respond to the attack with a military attack. She therefore officially regretted the assassination of the heir to the throne, denied any involvement and pointed out that all of the perpetrators came from Bosnia , which was annexed by Austria-Hungary , and were thus kuk subjects.

There were violent anti-Serb riots in Bosnia and Croatia. These were used by the Serbian press to make massive accusations against Austria-Hungary, which resulted in a real press war between Serbia and the Habsburg Empire. In Vienna the Serbian pronouncements were seen as evidence of Serb complicity in the assassination attempt. Serbia, on the other hand, invoked the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of the press in the country and saw the real problem focus in the officially influenced nationalist Austro-Hungarian press (especially the conservative Reichspost ).

Austria-Hungary

In Austria-Hungary, high-ranking military and politicians such as the Chief of the General Staff , Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf , the Austrian Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh and War Minister Alexander von Krobatin had been pushing for military action against Serbia for years. They believed that this was the only way to get over the Greater Serbian movement, which aimed at a connection of all south Slavic areas of the Habsburg Empire to Serbia. Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold , Emperor Franz Joseph I and above all the murdered heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand had so far opposed these plans.

After the attack, Conrad demanded an immediate attack against Serbia. Berchtold replied that such a step must be well prepared. On July 1, he informed the Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza that the Foreign Office had agreed to settle accounts with Serbia. But Tisza thought the moment was unfavorable and protested with a letter to Emperor Franz Joseph. The Hungarian Prime Minister also wanted to prevent the precarious equilibrium of the dual monarchy from being disrupted by a possible annexation of Serbia. Because an increase in Slavic subjects could have given the supporters of trialism a boost and weakened Hungary's position.

However, Conrad's plan of a quick and decisive surprise attack was not militarily feasible for the Austro-Hungarian Army, as it had a mobilization time of 16 days even in a limited war against Serbia. The chief of staff only wanted to achieve a state of war and exclude any surrender on the part of politics.

"Mission Hoyos" and "Blank Check"

At a meeting of the Council of Ministers in Vienna on July 2, 1914, no agreement could be reached with Tisza, but it was decided to send Legation Councilor Alexander Hoyos , the head of cabinet and closest advisor to Foreign Minister Berchtold, as an envoy to Berlin to find out whether there was German backing for military action.

Hoyos traveled to Berlin on July 5, 1914, and had a meeting there with Arthur Zimmermann , Undersecretary of State in the Foreign Office . Hoyos urged that the Habsburg Monarchy "take this opportunity to give a free hand against Serbia". After a meeting with the Austro-Hungarian ambassador Ladislaus von Szögyény-Marich , Kaiser Wilhelm II then issued the famous “ blank check ”, which Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg confirmed on July 6th. In a telegram he assured Austria-Hungary of the full and unconditional support of the Reich in an action against Serbia:

"Emperor Franz Joseph can, however, rely on S [a] M [ajestät] in harmony [...] and loyal to his old friendship by Austria-Hungary."

The fact that it was actually a blank power of attorney from the German side is largely undisputed. Sebastian Haffner believes that the decision to strike against Serbia was not made in Vienna, but on July 5, 1914 in Potsdam , specifically in the event that “serious European complications” should arise from it. But those responsible in Vienna also brought about the war with their eyesight, not only planning a locally limited war, but were also prepared to unleash a war spanning large parts of Europe because they believed that this would stabilize the multi-ethnic state of Austria-Hungary again and thus save it can.

Russian intervention

The danger of the Austrian approach lay in an intervention by Russia, which saw itself as the protective power of Serbia. In an (unprovoked) attack by Russia against Austria-Hungary, however, Germany had to come to the aid of its ally according to the two-tier agreement . A war between Russia and Germany in turn meant the fall of an alliance for France .

How much the Austro-Hungarian leaders expected Russian intervention is a matter of dispute in research. Foreign Minister Berchtold wrote on July 25th in a confidential telegram to his ambassador in Saint Petersburg Friedrich von Szápáry :

“At the moment when we decided to take serious action against Serbia, we were of course aware of the possibility of a clash with Russia that would develop out of the Serbian difference. […] We could not let this eventuality confuse our position towards Serbia, because fundamental state-political considerations put us before the need to put an end to the situation so that a Russian license would enable Serbia to threaten the monarchy with continuous and unpunished. "

Plans to partition Serbia

At the time of the Hoyos mission, there was still no agreement on what to do with Serbia after a military strike. In a letter dated July 2nd to Kaiser Wilhelm , which Hoyos handed over as part of his mission, Emperor Franz Joseph stated that the goal of his government was “the isolation and downsizing of Serbia”. This state is "the pivot of Pan-Slavic politics" and must therefore be " eliminated as a political power factor in the Balkans ". On July 5, Hoyos personally spoke to Zimmermann about a “complete partition” of Serbia, which Berchtold later presented as the Count's personal opinion after Tisza's protest.

In a Ministerial Council meeting on July 19, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian ministers agreed not to annex any Serbian territory if possible, but to weaken Serbia by ceding large areas to friendly Balkan states. In addition, it was decided to declare a territorial disinterest in other powers. Austro-Hungarian diplomats in St. Petersburg and London therefore repeatedly emphasized that they had no intention of conquering. Berchtold had the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Dmitrijewitsch Sasonow informed:

“That in our action against Serbia we do not intend to acquire any territorial territories and also do not want to destroy the independent existence of the kingdom at all. […] The monarchy is territorially saturated and has no desire for Serbian property. If the struggle with Serbia is forced upon us, it will not be a struggle for territorial gain for us, but merely a means of self-defense and self-preservation. "

However, the Austrian plans to downsize Serbia became known through indiscretions by Austro-Hungarian embassy staff in London. The German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg then expressed outrage at Vienna's “unbearable ambiguity” with regard to its war aims .

On July 29, the Austro-Hungarian government announced to the British government that it could not foresee what it would do after a victorious war. It is natural, however, that "all declarations regarding our disinterest only apply in the event that the war between us and Serbia remains localized".

Ultimatum to Serbia

On July 14th, the Austro-Hungarian ministers were able to agree with Tisza that after a planned French state visit to Russia, Serbia would be given a 48-hour ultimatum , the demands of which were to be so sharp “that a military conflict is likely. “The German ally was informed and urged that the ultimatum must be unacceptable. Berchtold, too, had already instructed the Austro-Hungarian envoy in Belgrade, Vladimir Giesl, on July 7, 1914 : “How always the Serbs react - you have to break off relations and leave; there must be war ”. The government tightened the first draft written by Friedrich Wiesner on July 8th and used formulations that Wiesner had expressly warned against.

The ultimatum was handed over on July 23 at 6 p.m. by the ambassador Giesl in Belgrade. It contained 10 demands to arrest Tankosić and Ciganović among others, to disband Narodna Odbrana and similar associations, to prevent all anti-Austrian publications and to dismiss all teachers, officers and officials accused of anti-Austrian propaganda . Points 5 and 6 were the most explosive.

"5. to agree that in Serbia organs of the Austro-Hungarian government cooperate in the suppression of the subversive movement directed against the territorial integrity of the monarchy; 6. to initiate a judicial investigation into those participants in the plot of June 28 who are on Serbian territory; Bodies delegated by the Austro-Hungarian government will take part in the relevant surveys; "

Most historians assume that the ultimatum was deliberately made unacceptable and should not be accepted at all. For example, Manfried Rauchsteiner states : “It was agreed that the coveted note should be sent to Serbia at the earliest possible point in time and that it be edited in such a way that Belgrade had to reject it” . This is also supported by the fact that on July 25, that is, one day before the deadline for the ultimatum expired, Baron Hold von Ferneck worked out a negative response to Serbia's reaction in the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry. If Serbia accepts all the conditions of the ultimatum, but also expresses the slightest protest, the reaction should be judged as inadequate for the following reasons: 1.) Because Serbia, contrary to its 1909 commitment towards Austria-Hungary, had adopted a hostile attitude, 2 .) Because it obviously called into question Austria-Hungary's power to hold Serbia accountable at its own discretion, 3.) because there was no question of an internal reversal of Serbia, although it was warned to do so several times, 4.) because it Serbia clearly lacks the honesty and loyalty to meet the terms of the ultimatum. Even if Serbia accepts all the conditions without objection, it can still be noted that it has neither taken the steps required in the ultimatum nor informed about them.

Christopher Clark, on the other hand, justifies the ultimatum by stating that, contrary to the official assurances, Serbia never started investigations against the perpetrators of the attack, which were appropriate to the gravity of the crime. The investigation was largely concluded a week after the attack. In addition, there have been far more serious demands in history that were not considered unacceptable, such as those that NATO made to Serbia in 1999 in the Rambouillet Treaty . John Keegan also sees nothing in the demand for investigations by the Austro-Hungarian authorities that other nations should have viewed as a violation of their principles, since Serbia, as he literally explains, at that time almost possessed the status of a “ rogue state ” in the eyes of the international community have.

Before the deadline set for Serbia had expired, the Serbian Chief of Staff and War Minister Radomir Putnik was arrested on July 25th in Budapest , who was traveling to Serbia from a cure in Bad Gleichenberg in Styria . However, Putnik was quickly released.

German Empire

One of the most controversial aspects of the July crisis has long been the assessment of the role of the German leadership.

After the attack, no activities or plans are initially documented. On July 3, however, the Saxon military commissioner at the German Federal Council , Traugott Leuckart von Weißdorf, had a conversation with the chief quartermaster in the general staff of the German Reich , Georg von Waldersee . Leuckart then reported to his government that Waldersee had said that war could break out overnight. In Leuckart's estimation, the General Staff would also welcome war. However, the emperor still hesitates.

Preventive war plans or belief in localization?

Since the Triple Entente was founded in 1907, Germany has felt increasingly encircled by its opponents . The General Staff in particular saw an existential military threat and firmly believed that the rearmament of Russia and France should serve to start a war around 1916. At this point in time, Chief of Staff Moltke believed that he could no longer win a war. That is why he has been pushing for a preventive war at an earlier point in time since 1908 . In the war council of December 8, 1912 , Wilhelm II discussed with the heads of the military whether the crisis caused by the First Balkan War should be used to bring about such a war. Since the head of the Reichsmarinamt Admiral Tirpitz was not yet adequately equipped, the plan was abandoned. However, the General Staff continued to warn the government urgently about what, in its opinion, was becoming increasingly explosive military situation, most recently in a memorandum dated May 15, 1914. Numerous historians such as Andreas Hillgruber and Imanuel Geiss are of the opinion that the assassination attempt in Sarajevo by the General Staff was greeted as a "golden opportunity" for war.

When the “blank check” was issued on July 5th, most of the participants on the German side apparently assumed that Russia would not intervene in an Austro-Serbian war. Hans von Plessen , Adjutant General Wilhelm II, noted in his diary after a conversation with the Kaiser, Minister of War Erich von Falkenhayn and Moriz von Lyncker , the head of the Imperial Military Cabinet:

"The prevailing opinion here is that the earlier the Austrians attack Serbia, the better and that the Russians - although they are friends of Serbia - do not participate."

War Minister Falkenhayn, on the other hand, wrote in a letter to Chief of Staff Moltke, who was staying in Karlsbad for a cure, that both he and Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg were of the opinion that Austria would ultimately not take a serious step. The deputy head of the Foreign Office, Arthur Zimmermann, is said to have spoken in the interview with Hoyos of "90 percent probability" that a big war would come. Nevertheless, he later said to confidants, he had urged the hesitant Chancellor to confirm the blank check. In the diary entries of Kurt Riezler , the closest confidante of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, it says on July 8th:

“An action against Serbia can lead to a world war. The Chancellor expects a war, whatever its outcome, to transform everything that exists [...]. If the war comes from the east, so that we go to the field for Austria-Hungary and not for us, we have the prospect of winning it. If the war does not come, if the Tsar does not want to, or if dismayed France advises peace, we still have the prospect of disengaging the Entente through this action. "

Towards the end of the war, Bethmann Hollweg herself confessed: “In a certain sense it was a preventive war”.

This contradicting source situation is a main reason for the research debate that continues to this day. Fritz Fischer assumed that the political leadership of Germany wanted to specifically bring about a European war in 1914 and thereby seek a grip on world power . Egmont Zechlin, on the other hand, was of the opinion that German politicians had deliberately accepted the risk of a world war, but not in order to implement world power plans, but rather to anticipate an imminent attack by Russia and France at a “more favorable time”, which was assumed to be certain. He says that German politicians had often expected the usual limited " cabinet war ", but the Entente responded with a " hegemonic war ". Since Bethmann Hollweg did not expect such a "fight out", he regarded the European war as an acceptable risk. Other researchers also see fear of Russia's rising power as a central motive of German politics. Although Germany's strength increased more and more, the “fatalistic” Bethmann Hollweg, the “self-doubting” Moltke and the “unstable” Wilhelm, with his fears of socialism, “yellow danger” and “Slavic flood”, held the time for the “last Billing "came. Lüder Meyer-Arndt believes that the German politicians felt bound by the "rash declaration" of Kaiser Wilhelm, which subsequently deprived them of their freedom of action. Gerd Krumeich advocates the thesis that the German government's demand that the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia must remain localized under all circumstances constituted a gross violation of the diplomatic usages of the time. The idea behind this was to examine Russia's willingness and willingness to go to war. If Russia does not respond to the demand for localization, it is important for Germany to wage war immediately before the tsarist empire rearms even more. The consequences of this blackmail strategy were not foreseen.

Preparing the ultimatum

On July 6th, the emperor started his planned vacation trip to Norway . It is controversial whether the public did not want to alarm the public by rejecting it, whether it was a deliberate deception about the seriousness of the situation or whether Bethmann Hollweg wanted the unpredictable Kaiser out of the way. Numerous other politicians and military officials also took their vacations. In return , Gottlieb von Jagow , the State Secretary in the Foreign Office, returned from his honeymoon on July 8th. As a result, the Foreign Ministry took the lead in politics. However, both Bethmann Hollweg on his estate in Hohenfinow and Georg von Waldersee at Ivenack Castle could be reached by telegram and both came to Berlin several times over the next two and a half weeks. The emperor also had a radio system on his yacht Hohenzollern and was kept up to date - albeit selectively.

In the talks with Hoyos and Szögyény-Marich on July 5th and 6th, both the Kaiser and Zimmermann and Bethmann Hollweg had spoken out in favor of a fait accompli as soon as possible . As a result, the German politicians in Vienna repeatedly urged to act as quickly as possible and to draft the planned ultimatum in an unacceptable manner. The German ambassador in Vienna, Heinrich von Tschirschky , kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold, declared that Kaiser Wilhelm had instructed him “to declare emphatically here that an action against Serbia is expected in Berlin and that in Germany it would not be understood if we Let the given opportunity pass without taking a blow. ”Another“ transigation ”(negotiating) with Serbia, as Berchtold interpreted, would be interpreted in Germany as an avowal of weakness.

The extent to which preparations for a major war have already been made is controversial. Fritz Fischer assumed that the ministerial rounds in Berlin on July 10, 15 and 18 served to prepare for war. Waldersee declared on July 17th:

"We're finished here in the general staff."

On July 22nd, Vienna informed the German government of the exact wording of the ultimatum. Officially, however, she insisted throughout the crisis that she was unaware of the Austro-Hungarian plans.

Russia

Since the middle of the 19th century, Russian politics had been shaped by the endeavor to gain the greatest possible control over the Balkans and thus over the Turkish straits, the Bosporus and Dardanelles, which are immensely important for Russian trade . However, since the end of the Second Balkan War in August 1913, Serbia had remained the only ally in the Balkans.

After the assassination attempt in Sarajevo, Saint Petersburg expected a “punitive action” by Austria against Serbia from the start. As early as July 7th, the Russian embassy in Vienna therefore launched a newspaper report that said there would be no protest if Austria asked for an investigation in Belgrade, but that Serbia's political independence would not be adversely affected. Similar warnings were issued to the government in Vienna on July 16 and July 18. Around July 17th, St. Petersburg learned from various sources that Austria was planning a “sharp” ultimatum.

From July 20 to 23, the French ally made a long-planned state visit to Saint Petersburg. There are no official minutes of the talks between the French President, the Russian Tsar, the French Foreign Minister and the French Prime Minister with the Russian government. The extensive inconclusive research on the conversations and results on the part of Soviet scientists and the editors of the official French collection of documents on the outbreak of the First World War and the gaps in the French documentation of the communication of the French ambassador to Russia lead the American historian Sean McMeekin to suspect that it is on the decline In 1914 a lot of material was destroyed. However, Christopher Clark has evaluated numerous unofficial documents that suggest that the French side called for a "solidarity" in the coming crisis. The final communiqué of the visit also shows “the full determination of the French government” to maintain loyalty to the alliance and to act jointly with the Russians. According to McMeekin, the French and Russian leaders did not decide to go to war, but were together ready to risk the war and not approve of future Austrian claims against Serbia regardless of their content.

According to Sean McMeekins, Russia began secretly mobilizing its army and the Baltic and Northern Fleets on July 25, 1914. Partial mobilization had started much earlier. McMeekin considers the Russians, with their old goal of wanting to rule the straits, to be primarily responsible for the outbreak of war. The measures in this regard were in accordance with the plans of a secret Russian military commission for the war preparation period, which was supposed to conceal the concentration of its own forces from the enemy, in particular through diplomatic negotiations.

Foreign Minister Sasonow and Nikolai Januschkewitsch , the chief of the Russian general staff, agreed in principle on July 24, 1914, a partial mobilization. Januschkewitsch sent a telegram to Warsaw on July 25, 1914 at 3:26 am that on July 26, 1914, war preparations would begin in the entire European part of Russia. On July 27, 1914, Janushkevich initiated war preparations in the districts of Omsk, Irkutsk, Turkestan and the Caucasus. Exercises and maneuvers were canceled, troops ordered into the quarters, military districts placed under martial law, fortresses placed in a state of war, crews increased, border guards fully manned, some reserve classes called up, censorship and security measures tightened, ports and railway lines mined and depots set up. According to Maurice Paleologue, the French ambassador to Russia, the actions on July 25, 1914 looked like mobilization. On July 26, 1914 at 3:25 p.m., the German military attaché in Russia Eggeling reported to Berlin about the Russian mobilization measures. The Belgian military attaché in Saint Petersburg reported on July 26th that the tsar had ordered the mobilization of ten army corps in the military districts of Kiev and Odessa. The German consuls in Russia reported alarming facts to the German ambassador in St. Petersburg Friedrich Pourtalès. On July 27, 1914, Austrian consuls in Kiev, Moscow and Odessa sent reports on this. There are also indications that the Russians began partial mobilization much earlier: At a relatively early stage of the Lviv offensive, Austro-Hungarian troops captured soldiers from Siberian and Caucasian units, which, given Russia's vast distances and enormous transport problems, hardly any could have reached the West if they were not mobilized until the end of July. Of course, all this does not mean that the tsarist government decided to go to war.

According to Clark, the alarm bells were ringing in Austria-Hungary because of the mobilization, but above all the measures increased massive pressure on Germany, which had so far refrained from military preparations.

The Russian leadership seems to have been determined not to accept any further diplomatic humiliation as in the Bosnian annexation crisis in 1908 and no further weakening of their position in the Balkans. Those responsible probably also feared a revolution in the event that they abandoned the “Slavic Brotherly People”.

France

The French state government does not seem to have expected dangerous political consequences after the attack. The decisive factor was probably the assessment of the experienced ambassador in London, Paul Cambon , who said that Austria-Hungary would certainly not hold Serbia responsible for an offense that was committed by kuk subjects. This changed suddenly when President Raymond Poincaré as well as Prime Minister and Foreign Minister René Viviani learned during the state visit to Saint Petersburg that Vienna was apparently planning a “sharp” ultimatum. Poincaré then declared that France would honor its alliance obligations in the event of war. This commitment is often referred to as a "second blank check".

In his work based on newly developed French sources, the historian Stefan Schmidt points out that, in addition to the desire for revenge for the defeat of 1870/71 and the return of Alsace-Lorraine, considerations of power and alliance politics have a strong influence on the way of thinking of the French leadership exercised. On the one hand, it was important to preserve France's reputation as a great power. On the other hand, people knew and feared the German preventive war considerations. That is why the alliance with Russia had the highest priority in foreign policy. However, the growing military power of the tsarist empire also made the French leaders fear that their allies might avoid their alliance obligations in a conflict with Germany that only affects French interests. So Poincaré and Maurice Paléologue , the French ambassador in Saint Petersburg, decided to assure Russia unconditional support of France, but in return demanded a swift Russian attack on East Prussia in the event of a war in order to undermine the German Schlieffen Plan . This French policy of «fermeté», of strength and firmness, was aimed at either deterring the German-Austrian dual alliance from a war against Serbia, or successfully waging a pan-European war, if it came: “Because on the one hand it was in In terms of domestic and foreign policy, it was necessary to burden the German Reich with war guilt and, in the course of a calculated maneuver, to give it the initiative to appeal to the military means of power, on the other hand it was necessary to ensure that Russia could launch an immediate and unrestricted attack on the German Reich stepped ”, summarizes Stefan Schmidt. Annika Mombauer stated that Chief of Staff Joseph Joffre and Minister of War Adolphe Messimy agreed on July 26th that “we will not be the first to take an initiative, but that we will take all precautionary measures that correspond to those of our enemies”. The French troops were kept ten kilometers behind the border so as not to be responsible for any border encroachments.

Great Britain

Great Britain was linked to France and Russia in the Triple Entente since 1907 . However, the Treaty of Saint Petersburg from that year contained no alliance obligations in the event of war. However, the government had signed a secret naval agreement with France. This provided that the entire French fleet was stationed in the Mediterranean. In return, Great Britain promised to protect the French Channel and Atlantic coasts. In the summer of 1914 it was a major concern of British policy to remain on good terms with Russia in order to prevent conflicts in the Near and Middle East from breaking out. However, due to improved relations with Great Britain in 1914, the German government hoped that the latter would not stand in for its Entente partners in the event of a conflict. To what extent the trust in British neutrality determined the policy of the German Reich leadership in the July crisis is still controversial among historians. While Fritz Fischer assumed that the entire calculation of the German government in the July crisis was based on English neutrality in the event of war, others such as Gerd Krumeich refer to British-Russian talks on a naval convention in the early summer of 1914. The German government had a spy find out about it. When the British government replied that there were no talks at all, it was "grist on the mill for the German government's phobia of encirclement".

On July 6th, the German ambassador in London, Karl Max von Lichnowsky, visited the British Foreign Minister Gray and expressed "privately" his fears that the Austro-Hungarian government might take military action against Serbia due to the anti-Serious atmosphere in the country and that because of the Russian armaments and the naval talks the German government could come to the conclusion "that it would be better not to hold back Austria and let the evil come now rather than later." Gray then tried to appease Lichnowsky that there were no signs that “the Russians are concerned, irritated or hostile towards Germany.” But he too is concerned about any developments in Austria-Hungary and, if entanglements arise, “will use all the influence at my disposal to reduce difficulties and get out of the To clear ways. ”Two days later, Gray told the Russian ambassador in London, A lexander Konstantinowitsch Benckendorff , "it would be very desirable if the Russian government ... wanted to do everything in their power to calm Germany down and convince it that no coup was being prepared against it."

When the British ambassador in Vienna, Maurice de Bunsen, warned several times over the next few weeks that Austria intended to humiliate Serbia and, according to its ambassador in Vienna, Nikolai Schebeko, Russia would assist Serbia in the event of war, this did not lead to enough in the British Foreign Ministry Excitement. In an interview with Paul Cambon, Gray said that he trusted that Germany would have a moderating effect on its ally.

Italy

The Kingdom of Italy was obliged by the Triple Alliance of 1882 to assist its allies Austria-Hungary and Germany in an attack by two other powers or in an unprovoked attack by France on a member. On July 1, 1914, the Italian Chief of Staff Alberto Pollio , who cooperated very closely with Germany and Austria-Hungary, died completely unexpectedly under circumstances that were not clarified and was replaced by Luigi Cadorna.

However, Berchtold deliberately failed to inform Italy and the Kingdom of Romania, which joined the Triple Alliance in 1883, of the intended action against Serbia, as he foresaw that they would only give their consent in return for compensation. But already on July 14th, the Italian Foreign Minister announced

"Our entire policy must be aimed at [...] preventing any territorial enlargement of Austria if this is not offset by adequate territorial compensation for Italy."

The Italian government made no attempts at mediation, but primarily pursued the question of possible compensations in the event of an annexation of Serbia by Austria-Hungary.

The reactions to the ultimatum

The Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia was viewed by the powers of the Triple Entente as an attack on the sovereignty of Serbia. The British Foreign Secretary Edward Gray, for example, described it as “brusque, sudden and imperious” and told the German Ambassador Lichnowsky that it exceeded everything he had ever seen in this way. He suggested that Germany and England should work together in Vienna to extend the deadline. He also suggested that if dangerous tensions arose between Austria-Hungary and Russia, the four powers that were not directly involved, England, Germany, France and Italy, should mediate.

According to research by the Italian historian Luciano Magrini, the Serbian government initially “resigned” on 23 July and considered accepting the ultimatum on all points, but was encouraged by Russia to take a tougher stance (see below). According to other authors, it has not been clarified whether and to what extent the corresponding telegram, which did not arrive until July 25, influenced the response of the Serbian government. Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov said that the tough demands were out of proportion to the failures that the Serbian government could possibly be blamed for. The destruction of Serbia and the balance of power in the Balkans must be prevented. The Russian Council of Ministers, the Privy Council and the Tsar decided on July 24th and 25th to mobilize the military districts of Odessa, Kiev, Kazan and Moscow in the event of an Austrian declaration of war on Serbia. On July 24th, the Council of Ministers issued a notification memorandum to Serbia, according to which Russia would urge the major European powers to extend the deadline for the ultimatum to enable “a detailed investigation into the assassination attempt in Sarajevo”. The memorandum also states that Russia will withdraw its funds from Germany and Austria and will not remain inactive in the event of an Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia.

On the evening of July 25th at 5:55 p.m. Serbia, which had already implemented general mobilization at 3 p.m., presented a response to the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum. In it it promised to fulfill most of the points, but rejected the participation of Austro-Hungarian officials in investigations in Serbia:

“The royal government naturally considers it its duty to initiate an investigation against all those persons who were involved in the plot of 15/28. June were or should have been involved and who are in their field. As far as the participation of organs of the Austro-Hungarian government specially delegated for this purpose in this investigation is concerned, it cannot accept such an investigation, as this would be a violation of the Constitution and the Criminal Procedure Act. But in individual cases the Austro-Hungarian authorities could be informed of the results of the investigation. "

The answer was seen by the Entente Powers as largely accommodating, but was rejected by Austria-Hungary as "insufficient" and "filled with a spirit of insincerity". The German government supported this view. She rejected all attempts at mediation on the grounds that Austria-Hungary could not be brought before a European court because of its conflict with Serbia.

Emperor Wilhelm II, who returned from vacation on July 27th, saw the Serbian response as a "humble surrender", with which there was no reason to go to war. Wilhelm suggested that Austria should only occupy Belgrade as a "bargaining chip" in order to enforce his demands. However, the German government passed this suggestion on to Vienna with a delay and mutilated. British Foreign Secretary Gray made a very similar proposal on July 29th. He said that after an occupation of Belgrade, Austria should announce its terms, which could be negotiated. This proposal was forwarded to Austria-Hungary by the German government on July 30, but rejected there. The French President Poincaré also rejected him, so that the French Prime Minister Viviani no longer supported him.

While many historians see the Austro-Hungarian refusal to accept this proposal as a mistake, Christopher Clark considers the British mediation proposals to be unrealistic, as they either did not bring Austria-Hungary any real advantages or were not enforceable against France and especially Russia.

From the Austro-Serbian to the great European war

While the mediation efforts were still ongoing, Austria declared war on Serbia on July 28th, because Count Berchtold wanted to break the ground for any attempt at intervention and create a fait accompli. In order to get Emperor Franz Josef's signature on the declaration of war, he mentioned a Serbian attack at Temes Kubin , which however probably never took place. The actual acts of war probably began with a bombardment of Belgrade on July 29th a few minutes before one o'clock in the morning by the DDSG ship Inn and several Austro-Hungarian monitors . The spectators gathered on the Semlin bank believed that this incident would end when the Serbs blew up individual fields of the railway bridge between Belgrade and Semlin shortly afterwards at two o'clock in the morning and the kuk howitzer battery opened fire on the Semlin side. At this point Belgrade was already partially evacuated. The massive bombardment of Belgrade by artillery and the Austro-Hungarian Danube flotilla, which Conrad von Hötzendorf had planned for a long time, had begun. Although it was militarily insignificant, it had a political impact, since Austria-Hungary now rejected all attempts at mediation as “arrived too late”.

Russia responded with partial mobilization on July 29th. Foreign Minister Sasanow assured the German ambassador Pourtalès that this mobilization was only directed against Austria-Hungary and that there were no measures against Germany. Among other things, however, the new research by Christopher Clark shows that extensive preparatory measures were already underway in the military districts facing Germany. At the same time, Sazanov tried to find a peaceful solution on the condition that it was not directed against the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Serbia. Berchtold's declaration of July 28, 1914, that after Russia had received his assurance that Austria would not seek to acquire territory, no right to intervene remained ineffective because Sasonov feared that Serbia would be "pushed down" to become an Austrian "satellite state".

Some historians like Sean McMeekin and Christopher Clark interpret Russian mobilization as a decision to go to war. However, this assumption is not mandatory. It might as well have been a threatening scenario or a mere precaution, given that Russia had weeks of mobilization.

The French government was only fully operational again on July 29, due to the return home from Saint Petersburg and received news of the partial Russian mobilization on the night of July 30. She asked the allies to act as openly and challengingly as possible in order not to provoke German mobilization. While Foreign Minister Viviani was open to a negotiated solution in the spirit of the British mediation offers, it had priority for Poincaré and the top of the military to persuade England to openly promise an alliance in order to decisively strengthen both the threat against the two alliance and their own position in the event of war.

The Russian mobilization created a predicament for the German military. The Schlieffen Plan , to which there was no alternative, provided for the Russian mobilization time to be used to defeat France. Since it was assumed that Russia would need several weeks to mobilize the army, after the Russian mobilization they gave in to pressure from the military in favor of a quick offensive in the west. The option that Russia could mobilize and be ready to negotiate at the same time was not included in the German scenario. The German government therefore announced in Saint Petersburg that progress of the Russian measures would have to be responded to with mobilization. Russia, however, mobilized the entire army on July 30th. The German Chief of Staff Helmuth von Moltke and Minister of War Erich von Falkenhayn pushed for a German mobilization so as not to lose valuable time.

While Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg was still hesitant, Moltke urged his Austrian colleague Conrad von Hötzendorf to mobilize the whole country, which took place on July 31. On the same day, Germany announced the “state of imminent danger of war” and gave Russia an ultimatum of 12 hours within which the Russian general mobilization was to end. Another 18 hour ultimatum to France demanded its neutrality in the event of a German-Russian conflict. In order to prevent France from initially declaring itself neutral and later entering the war, which would have sabotaged the Schlieffen Plan, Ambassador Wilhelm von Schoen was supposed to demand the border fortresses of Verdun and Belfort as a pledge for French neutrality. This did not happen because the French government replied that France would act “according to its interests”.

After there was no Russian answer, Berlin had the German army mobilized on August 1st . At around 8 p.m., the German ambassador Friedrich Pourtalès telegraphed the Foreign Office that he had asked Foreign Minister Sasonov three times whether he could give the required declaration regarding the cessation of the war measures and, after three negative responses, handed over the ordered declaration of war. Since France had evasively answered the ultimate German demand for neutrality, the German declaration of war on France followed on August 3. Ambassador Wilhelm von Schoen presented the declaration of war to President Poincaré on the grounds that French military pilots had carried out hostile acts against Germany ( plane from Nuremberg ) and violated Belgium's neutrality by flying over them.

Following the German decision to occupy neutral Belgium first to conquer France, as provided for in the Schlieffen Plan , Great Britain threatened war. Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg asked the British Ambassador Edward Goschen not to break the peace because of a "scrap of paper" - what was meant was the international guarantee of Belgian neutrality from 1839. Great Britain, however, declared Germany on August 4th after its invasion Belgium, the war.

The public crisis

For a long time, the public did not perceive the crisis as such. Although Austria-Hungary was generally expected to take a "step" against Serbia after the attack, they trusted the official assurances that no interference with Serbian sovereign rights was planned. When the ultimatum became known, a large part of the German-speaking press thought it was justified. There are indications that the German government exerted influence in advance. For example, the Legation Counselor in the Foreign Office, Ernst Langwerth von Simmern , instructed the Chargé d'affaires of the government in Hamburg to inform the editors-in-chief of Hamburger Nachrichten , the correspondent and the Hamburger Fremdblatt that war could best be avoided if Germany were calm and stand firmly on the side of Austria-Hungary. The SPD called on July 25 in the forward up at anti-war rallies on 28 July. It is estimated that 500,000 to 750,000 people took part across Germany, around 20 percent of whom were women. There were occasional clashes with the police or with national demonstrators. On the other hand, German national students, the Young Germany Federation and parts of the “middle-class public” celebrated the Serbian rejection on July 25th and 26th with street rallies.

In the days that followed, there were also mass crowds in German city centers, especially in Berlin. This was also due to the fact that the people there were the quickest to find out about the latest developments through extra leaflets , notices on advertising pillars or official announcements.

On August 2, the German population learned from the press of the first Russian attacks in East Prussia , but not that their own government had declared war on Russia the day before. Also on August 2, rumors of French border violations such as bombing near Nuremberg emerged , which were passed on to the press as officially confirmed news on August 3, although they had already been identified as "Tatar reports" at that time . To have been raided faith by both Russia and France treacherous, while the own emperor was allegedly tirelessly for peace, in Germany led to a closing of ranks of almost all political forces and a large consent to war. The feeling of being drawn into the war without guilt also existed in the other participating countries. The retreating soldiers were enthusiastically bid farewell in many places.

Assessing the July Crisis

After the end of the war, the sole responsibility of the Central Powers for the outbreak of war was enshrined in the Paris suburb agreements. In the Versailles Treaty , which the victorious states concluded with Germany, it says in § 231:

“The Allied and Associated Governments declare, and Germany recognizes, that Germany and its allies are responsible, as the originators, for all loss and damage suffered by the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals as a result of the war forced upon them by the attack on Germany and its allies to have."

Almost all Weimar parties and the vast majority of the German public rejected this assignment of blame. Initial efforts to investigate the actions of those responsible before the war and to punish them legally were nipped in the bud. Although there was extensive preoccupation with the events of the July crisis in the Weimar Republic , it was almost exclusively designed as "innocence research" and was intended to serve a treaty revisionism. The anti- republican parties, especially the DNVP and the NSDAP , used the " war guilt lie " to fight the Weimar Constitution .

Controversy after 1945

The discussion about the assessment of the July crisis and thus the war guilt flared up again in October 1959 through an essay by the Hamburg historian Fritz Fischer - German War Aims - Revolutionization and Separate Peace in the East 1914–1918 - and above all through his book Griff nach der Weltmacht (1961) on. Fischer drew the conclusion:

“Since Germany wanted, wished for and covered the Austro-Serbian war and, trusting in German military superiority, deliberately let it come down to a conflict with Russia and France in 1914, the German Reich leadership bears a considerable part of the historical responsibility for the outbreak of a general war. "

This led to the so-called Fischer controversy , in which, in the opinion of Volker Ullrich, no agreement has been reached to this day: "If one leaves aside the older apologetic version of" slipping into "the European powers into the world war, which has hardly any advocates, there are essentially three different interpretations ":

- The first group around Fritz Fischer and his students tried to prove that the Reich leadership had provoked a continental war with Russia and France in order to achieve hegemony in Europe and thus world power.

- The second group around Wolfgang J. Mommsen and Hans-Ulrich Wehler chose the domestic political approach: internal difficulties and inability to reform would have caused a “flight to the front” in order to stabilize the endangered position of the traditional elites through external aggression ( social imperialism ).

- The third group with Egmont Zechlin , Karl Dietrich Erdmann , Andreas Hillgruber and Klaus Hildebrand regards German politics in the July crisis as being strategically motivated in terms of foreign policy. In order to break the diplomatic isolation, a policy of “calculated risk” was pursued, but localization of the Austro-Serbian conflict failed.

Another point of discussion in German research was that, in the opinion of many historians, German policy during the July crisis “was largely determined by purely military-technical considerations, much more than that of other states. The helpless dependence of the German political leadership on the plans of the military was the main reason for their failure at the crucial moment ”. For Gerhard Ritter , Bethmann Hollweg, but also Chief of Staff Moltke , who collapsed after the start of the war, were helpless victims of the circumstances. According to Ritter, they were led to war against their will, forced by the “relentlessness of military deployment plans” for which they were not responsible and whose consequences had never been properly foreseen. In the eyes of Ritter and others, the dire inflexibility and the mistakes of German politics in the July crisis were caused by the Schlieffen Plan . The rigidity of the German military plans, which knew no alternative, was primarily responsible for the expansion of the conflict into the world war. This was due to the fact that the leadership structure of the German Reich was characterized by a juxtaposition of political and military leadership “below” the monarch, who was only formally integrating. At the decisive moments, German diplomacy was “referred to a serving role in shielding military planning”. Ultimately - according to Hillgruber - the preventive war concept of the General Staff prevailed.

Eberhard von Vietsch particularly emphasizes that a real discussion about the necessity or futility of war in Germany did not take place during the crisis.

“This was most disturbing in the highest state sphere itself, namely in the decisive meeting of the Prussian State Ministry at the end of July, where not even the ministers dared to ask more than a few interim questions of a secondary nature to the statements of the leading statesman, which led to the struggle for existence Brought sight. On the other hand, in the Council of Ministers in Vienna, the great fundamental questions of the monarchy were discussed in those days with a completely different sharpness and urgency. In Prussia Germany, however, even the highest state officials still acted as mere orders. "

From his point of view, Jürgen Angelow summarized the German research trend in 2010 as follows:

“In dealing with Fritz Fischer's theses, the view that prevailed in German historiography that the actions of the Reich leadership during the July crisis in 1914 resulted from a defensive position in foreign policy. The improvement in one's own position found to be necessary should be implemented with the help of a 'policy of limited offensive', while accepting a 'calculated risk'. The risk of their failure lay in being forced to wage a major war whose chances of victory were judged more and more skeptically by the relevant military from year to year. […] In fact, the terms “limited offensive” and “calculated risk” do not fully express the irresponsible and cryptic of the German position. In contrast, the term ' brinkmanship ' used by younger historians describes a daring policy of 'uncalculated risk', of walking on the edge of the abyss. "

Controversy over The Sleepwalkers

In 2013, the Australian historian Christopher Clark, in his bestseller Die Schlafwandler, called for a perspective that focuses less on Germany and more on the behavior of other nations. His conclusion:

“All [major European powers] believed that they were acting under pressure from outside. Everyone believed that the war was being forced upon them by their opponents. However, all made decisions that contributed to escalating the crisis. In this respect, they all bear responsibility, not just Germany [.] "

However, other historians such as Gerd Krumeich, Stig Förster , Volker Ullrich and Heinrich August Winkler accused Clark of playing down the German role. Also Annika Mombauer argues in her book The July crisis against Clark's thesis and says that the war was were mainly caused deliberately by Germany and Austria-Hungary. In connection with the role of these two countries, the " Mission Hoyos " is reminded again. In Germany, however, Clark's theses received support from Jörg Friedrich , Hans Fenske and Herfried Münkler , who came to similar conclusions about the causes of the war in their works on the First World War.

Clark replies to his critics that he had absolutely no intention of acquitting German politics, but that there is a different distribution of interest in his book than in the Fischer school, for example. It was his aim to make the interactive and European in the catastrophe visible. Clark regards the violent reactions, especially from German historians, as motivated by historical policy :

“In some puzzling way the war guilt thesis of World War I is related to the guilt complex of World War II . And here the Germans are undoubtedly dealing with a historically and morally unique legacy that results not only from the criminality of the Nazi regime, but also from the hundreds of thousands of fellow travelers and accomplices. Sometimes I get the feeling with the critics of my book that they believe that if you shake any part of the guilt complex in the twentieth century, the whole structure will shake. But I don't see it that way. Because there will never be a debate about the outbreak of the Second World War like the one about the First. "

In a discussion with Christopher Clark at the Historikertag 2014 in Göttingen, Gerd Krumeich put forward the thesis that there is currently no real debate about July 1914, but a "Clark debate". The phenomenal sales success showed that the book apparently satisfied a German longing that "two years ago we had no idea that we even had it." In addition, the question arises why all German journalists would have read the book differently, when Clark meant it, namely as relief for Germany, and then wrote these “insane eulogies”. The “Clark Phenomenon” is worth a book of its own, as it is infinitely important to understand what was raging in German society and why so many suddenly felt “redeemed” by Clark's book.

In a contribution for the world , the historians Sönke Neitzel , Dominik Geppert and Thomas Weber as well as the journalist Cora Stephan wrote that the research of Clark and Sean McMeekin initiated a paradigm shift that had serious consequences not only for the observation of history, but also for that Picture of European unification and therefore met with politically motivated criticism:

“Recent historical research on the causes and course of the war contradict the idea that the German Reich provoked Great Britain through its striving for world power and that its lust for power had to be stopped with united forces. This view, however, is based on the concept of Europe, according to which Germany must be 'integrated' supranationally so that it does not cause mischief again [...] Some do not like the new historical findings because they contradict their beloved self-image and enemy image. Some do not like the interpretations of the July crisis, which do not deny the German contribution, but put it in reasonable proportions. But we are no more entitled to pride in guilt than a triumphant acquittal. German self-centeredness is counterproductive. Above all, the current crisis makes it clear that a Europe based on historical fictions is failing. False lessons from the past could prove fatal to the European project. [...] 'EU or war' is the wrong alternative and cannot be derived from the history of the world wars. "

Heinrich August Winkler was particularly critical of this point of view :

“Even more absurd are the national, even nationalistic tones that the four world authors use. If they accuse the German supporters of the supranational unification of Europe that they ultimately want, insofar as they are consistent, a Europe without nations, they serve moods and resentments to which the AfD and sometimes the CSU have been appealing for some time. The postulate of historiography 'without normative ballast', as one of the authors of the World Manifesto, Sönke Neitzel, recently put forward in a different context, is completely misleading. A historical scholarship that follows this motto would either end up in flat positivism or with that specifically German understanding of 'realpolitik' that helped lead Germany on to the First World War. It is time for the revisionists to revise themselves. "

See also

literature

- Jürgen Angelow : The way to the original disaster. The disintegration of old Europe. Be.bra, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-89809-402-3 .

- Jürgen Angelow, Johannes Großmann (ed.): Change, upheaval, crash. Perspectives on the year 1914 , Steiner, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-515-10913-0 .

-

Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe went to War in 1914. Allen Lane, London et al. 2012, ISBN 978-0-7139-9942-6 .

- German: The sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Translated from the English by Norbert Juraschitz. DVA, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 .

- Karl Dietrich Erdmann (Ed.): Kurt Riezler . Diaries-Essays-Documents. Introduced and edited by Karl Dietrich Erdmann. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, ISBN 3-525-35817-2 (important source work, Riezler was a collaborator and confidante of Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg).

- Fritz Fischer : Reach for world power. Droste, Düsseldorf 1984, ISBN 3-7700-0902-9 , pp. 46-86 (1st edition 1961).

- Fritz Fischer: War of Illusions. German politics from 1911–1914. 2nd Edition. Droste, Düsseldorf 1970, ISBN 3-7700-0913-4 , pp. 663-738.

- Fritz Fischer: July 1914: We didn't slide into it. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1983, ISBN 3-499-15126-X .

- David Fromkin : Europe's last summer. The seemingly peaceful weeks before the First World War. Blessing, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-183-9 .

- Imanuel Geiss (Ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war 1914. A collection of documents. Volume I. Edited and introduced by Imanuel Geiss. With a foreword by Fritz Fischer. Publishing house for literature and contemporary history, Hannover 1963 DNB 451465695 .

- Imanuel Geiss (Ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war 1914. A collection of documents. Volume II. Edited and introduced by Imanuel Geiss. Publishing house for literature and contemporary history, Hanover 1964.

- Imanuel Geiss (Ed.): July 1914. The European crisis and the outbreak of the First World War. 3. Edition. dtv, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-423-02921-8 (selection of the most important documents from Geiss 1963/64).

- Imanuel Geiss: The long way to catastrophe. The prehistory of the First World War 1815–1914. 2nd Edition. Piper, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-492-10943-8 .

- Dieter Hoffmann: The leap into the dark or how World War I was unleashed. Militzke, Leipzig 2010, ISBN 978-3-86189-827-6 .

- James Joll: The Origins of World War I. List, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-471-77870-5 .

- Gerd Krumeich : July 1914. A balance. Schöningh, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-506-77592-4 .

- Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914. How Germany stumbled into the First World War. Böhlau, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-412-26405-9 .

- Annika Mombauer: The July crisis. Europe's way into the First World War . Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66108-2 .

- Christa Pöppelmann: July 1914. How to start a world war and plant the seeds for a second. A reader. Scheel, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9804198-6-4 .

- Stefan Schmidt: France's foreign policy in the July crisis 1914. A contribution to the history of the outbreak of the First World War. (= Paris historical studies. 90). Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59016-6 , online at perspectivia.net .

- Wolff, Theodor: The war of Pontius Pilatus. Oprecht & Helbling, Zurich 1934, online on Projekt Gutenberg-DE

Movie

- 1914, the last days before the world fire . D 1931, historical film , 111 min.

- Sarajevo 1914: an assassination attempt and the consequences . A 2004, documentary , 45 min.

- Europe's last summer: The July crisis (= episode 3 of the series Vom Reich zur Republik ). D 2012, docu-drama, 90 min.

- 30 days to go until the war - the German Empire and the July crisis in 1914 . D 2012, documentary, 30 min.

- 37 days . GB 2014, 3-part docu-drama , a total of 177 min.

- Sarajevo - The Road to Disaster . D 2014, documentary / docu-drama , 45 min.

Web links

- July Crisis on firstworldwar.com (English)

- The World War I Document Archive of the Brigham Young University Library (English)

- Karl Kautsky's German documents on the outbreak of war in 1914 at archive.org

- Dieter Hoffmann: July crisis - the longed-for world war. In: one day . April 13, 2010

- How the First World War came about - impressions from the history symposium. Lecture by Professor Gerhard Hirschfeld at the history symposium “100 Years of the First World War” at the State Media Center Baden-Württemberg , May 14, 2014. Archived from the original (no longer online) in the Internet Archive , video recording availablein three parts on Youtube : Part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Letter from Count Berchtold to Freiherr von Giesl in Belgrade (ultimatum to Serbia)

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Drew into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 , p. 89; however, on p. 496, Clark attributes this assumption to Luigi Albertini .

- ↑ Wiesner's telegram of July 13, 1914 at World War I Document Archive

- ↑ Friedrich Wiesner: The murder of Sarajevo and the ultimatum. Reichspost (June 28, 1924), p. 2 f.

- ↑ quoted from Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2013, p. 582.

- ↑ Brigitte Schagerl: In the service of a state that should no longer exist, no longer existed, was no longer allowed to exist. Friedrich Ritter von Wiesner. Diplomat, legitimist, victim of Nazi persecution . Vienna 2012, p. 54 ff . ( online on the website of the University of Vienna [PDF; 8.8 MB ] dissertation).

- ↑ a b Sebastian Haffner : The seven deadly sins of the German Empire in the First World War . Verlag Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1981, ISBN 3-7857-0294-9 , p. 26.

- ↑ Christa Pöppelmann: July 1914. How to start a world war and plant the seeds for a second. A reader. Clemens Scheel Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9804198-6-4 , p. 37 f.

- ↑ Christa Pöppelmann: July 1914. How to start a world war and plant the seeds for a second. A reader. Clemens Scheel Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-9804198-6-4 , p. 70 ff.

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Red Book. Diplomatic files on the prehistory of the war in 1914. Popular edition. Manzsche kuk Hof-Verlags- und Universitäts-Buchhandlung, Vienna 1915, Doc. 19, pp. 32–48.

- ^ Lecture by the Hungarian Prime Minister Count Tisza

- ↑ William Jannen, Jr: The Austro-Hungarian Decision For War in July 1914. In Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., Peter Pastor (Ed.): Essays on World War I: Origins and Prisoners of War . New York 1983, pp. 55-81, here: p. 72; and József Galántai: István Tisza and the First World War. In: Austria in history and literature. 8 (1964), pp. 465-477, here: p. 477.

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson, Jr .: Vienna and July 1914: The Origins of the Great War Once More. In: Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., Peter Pastor (Eds.): Essays On World War I: Origins and Prisoners of War . New York 1983, ISBN 0-88033-015-5 , pp. 9-36, here: pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Friedrich Kießling: Against the “great” war? Relaxation in international relations 1911–1914 . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56635-0 , p. 259 f.

- ^ Report by Count Szögyény

- ^ Szögyény telegram

- ^ Karl Kautsky: The German documents on the outbreak of war in 1914. Published on behalf of the Foreign Office. Volume 1, German Publishing Society for Politics and History, Berlin 1921, p. 32 f.

- ^ Norman Stone : Hungary and the Crises of July 1914. In: The Journal of Contemporary History 1, No 3 (1966), pp. 153–170, here: p. 167.

- ↑ a b telegram to Szapary

- ^ Letter from Emperor Franz Joseph ; Ludwig Bittner , Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs . Vienna / Leipzig 1930, Volume 8, pp. 250 ff. (No. 9984)

- ↑ Kautsky Volume 1, p. 35 ; József Galántai: Hungary in the First World War . Budapest 1989, ISBN 963-05-4878-X , p. 34.

- ^ Minutes of the meeting

- ^ Walter Goldinger : Austria-Hungary in the July crisis 1914. In: Institute for Austrian Studies (ed.): Austria on the eve of the First World War . Graz / Vienna 1964, pp. 48–62, here p. 58.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hanover 1963/64. Volume 1, pp. 345 ff., 408 and 448 f.

- ↑ Count Berchtold on July 14th

- ↑ Kautsky: Volume 1, et al., Pp. 93 and 113 ff

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle: Austria-Hungary and the First World War . Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 75.

- ↑ Cf. Brigitte Schagerl: In the service of a state that should no longer exist, no longer existed, was no longer allowed to exist. Friedrich Ritter von Wiesner. Diplomat, legitimist, victim of Nazi persecution . Vienna 2012, p. 63 ( online on the website of the University of Vienna [PDF; 8.8 MB ] dissertation).

- ^ The ultimatum to Serbia

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The Death of the Double Eagle: Austria-Hungary and the First World War . Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 79.

- ↑ Vladimir Ćorović: Odnosi između Srbije i Austro-Ugarske u XX veku . Biblioteka grada Beograda, Belgrade 1992, ISBN 86-7191-015-6 , p. 758.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, p. 502 ff.

- ^ John Keegan, The First World War - A European Tragedy (2003), p. 91.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle: Austria-Hungary and the First World War. Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-222-12116-8 , p. 118 f.

- ↑ The "Council of War" (December 1912)

- ↑ Annika Mombauer: Helmuth Von Moltke and the Origins of the First World War. Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-521-79101-4 , pp. 177 f.

- ↑ Andreas Hillgruber: The failed great power. A sketch of the German Empire 1871–1945 . Düsseldorf 1980, p. 47; and Imanuel Geiss: The Outbreak of the First World War and German War Aims. In: The Journal of Contemporary History. 1, No 3 (1966), pp. 75-91, here: p. 81.

- ↑ Meyer-Arndt p. 28.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents. Hanover 1963, Volume 1: No. 23.

- ↑ Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914. How Germany stumbled into the First World War. Böhlau, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-412-26405-9 , p. 25.

- ^ Karl Dietrich Erdmann (Ed.): Kurt Riezler. Diaries-Essays-Documents. Introduced and edited by Karl Dietrich Erdmann. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1972, ISBN 3-525-35817-2 , p. 182 ff. It should be noted that Erdmann's edition of the Riezler diaries is not accepted by all historians: the source value of the Riezler diaries, their authenticity and Erdmann's editions were, for their part, the subject of intense controversy; see. Bernd Sösemann: Kurt Riezler's diaries. Investigations into their authenticity and edition. In: Historische Zeitschrift 236, 1983, No. 2, pp. 327-369, and the reply by Karl Dietrich Erdmann: On the authenticity of Kurt Riezler's diaries. An anti-criticism. In: Historische Zeitschrift 236, 1983, issue 2, pp. 371-402.

- ↑ Andreas Hillgruber: Germany's role in the prehistory of the two world wars . Göttingen 1979, ISBN 3-525-33440-0 , p. 57.

- ^ Egmont Zechlin: Problems of the war calculation and the end of the war in the First World War. In: Egmont Zechlin: War and War Risk. On German politics in the First World War. Essays . Düsseldorf 1979, p. 32-50, here: p. 39 f.

- ↑ William Jannen, Jr: The Austro-Hungarian Decision For War in July 1914. In Samuel R. Williamson, Jr., Peter Pastor (Ed.): Essays on World War I: Origins and Prisoners of War . New York 1983, pp. 55-81, here: p. 73.

- ↑ Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914. How Germany stumbled into the First World War. Böhlau, Cologne 2006, ISBN 3-412-26405-9 , p. 40.

- ^ Gert Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Paderborn 2014, p. 13.

- ↑ About it Berchtold to Tisza ; Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs . Vienna / Leipzig 1930, volume 8, p. 370 f. (No. 10145).

- ↑ Kautsky: Volume 1, p. 102.

- ^ Kautsky: Volume 1, p. 128.

- ^ Kautsky: Volume 2, p. 47.

- ^ Clark: Sleepwalkers, p. 427.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: Russia's Road to War. The First World War - the origin of the catastrophe of the century. Europa Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-944305-63-9 , p. 81 ff.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin , Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1982, ISBN 3-406-04124-8 , p. 286 f.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: Russia's Road to War. The First World War - the origin of the catastrophe of the century. Europa Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-944305-63-9 , p. 94.

- ↑ on this in detail Sean McMeekin: Russia's path to war. The First World War - the origin of the catastrophe of the century. Europa Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-944305-63-9 , p. 104 ff.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: Russia's Road to War. The First World War - the origin of the catastrophe of the century. Europa Verlag, Berlin / Munich / Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-944305-63-9 , p. 102 ff. Also Clark: Die Schlafwandler. 2013, p. 608 ff.

- ↑ Clark: The Sleepwalkers. 2013, p. 615.

- ↑ Michael Fröhlich: Imperialism. German colonial and world politics. 1880-1914 . DTV, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-423-04509-4 , p. 134.

- ↑ Gerd Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Schöningh, Paderborn 2013, p. 86.

- ^ Stefan Schmidt: France's foreign policy in the July crisis 1914. A contribution to the history of the outbreak of the First World War. (= Paris historical studies. Volume 90). Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59016-6 , p. 356. Online perspectivia.net.

- ^ Stefan Schmidt: France's foreign policy in the July crisis 1914. A contribution to the history of the outbreak of the First World War. (= Paris historical studies. Volume 90). Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59016-6 , p. 361. Online perspectivia.net.

- ↑ Annika Mombauer: The July crisis. Europe's way into the First World War. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66108-2 , p. 90.

- ↑ Gerd Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Schöningh, Paderborn 201, p. 35.

- ↑ Gerd Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Schöningh, Paderborn 2013, p. 48.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents. Hanover 1963, Volume 1: No. 38.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents. Hanover 1963, Volume 1: No. 56.

- ↑ Gerd Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Schöningh, Paderborn 2013, p. 95 ff.

- ^ Giovanni d'Angelo, La strana morte del tenente generale Alberto Pollio. Capo di stato maggiore dell'esercito. 1º luglio 1914, Valdagno, Rossato, 2009.

- ^ Hugo Hantsch: Leopold Graf Berchtold. Grand master and statesman . Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1963. Volume 1, p. 567.

- ^ Leo Valiani: Negotiations between Italy and Austria-Hungary 1914–1915. In: Wolfgang Schieder (Ed.): First World War. Causes, origins and aims of the war . Cologne / Berlin 1969, p. 317-346, here: p. 318 f.

- ^ Robert K. Massie : The Bowls of Wrath. Britain, Germany and the pulling up of the First World War . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-596-13497-8 , pp. 756 f.

- ↑ Kautsky Volume 1, p. 169 ff.

- ↑ Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2013, pp. 591–593; Gerd Krumeich : July 1914. A balance. Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-506-77592-4 , p. 128 ff.

- ↑ Volker Berghahn : Sarajewo, June 28, 1914. The fall of old Europe. Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-423-30601-7 , p. 105; Günther Kronenbitter: "War in Peace". The leadership of the Austro-Hungarian army and the great power politics of Austria-Hungary 1906–1914 . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56700-4 , p. 497.

- ↑ Notifying memorandum of the Russian Council of Ministers to Serbia from 11./24. July 1914.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, p. 599.

- ^ Text of the Serbian note

- ↑ Kuk-Zirkulnarnote of 28 July

- ↑ Kautsky Volume 1, p. 241 f.

- ↑ Kautsky: Volume 2, p. 18 f.

- ↑ Kautsky: Volume 2, p. 38 f. ; Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hannover 1963, Volume 2, p. 378 (No. 789); Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs . Vienna / Leipzig 1930, Volume 8, p. 910 (No. 11026).

- ↑ Kautsky Volume 2, p. 86 f.

- ↑ a b Stefan Schmidt: France's foreign policy in the July crisis 1914. A contribution to the history of the outbreak of the First World War. (= Paris historical studies. Volume 90). Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-59016-6 , p. 359. Online perspectivia.net.

- ↑ Clark: Sleepwalkers. P. 488 ff.

- ↑ Christopher Clark: The Sleepwalkers. How Europe moved into World War I. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, p. 602.

- ↑ Günther Kronenbitter: "War in Peace". The leadership of the Austro-Hungarian army and the great power politics of Austria-Hungary 1906–1914. Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56700-4 , p. 484.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hanover 1964, Volume 2, p. 718 f. Walter Goldinger: Austria-Hungary in the July crisis 1914. In: Institute for Austrian Studies (Hrsg.): Austria on the eve of the First World War . Graz / Vienna 1964, pp. 48–62, here p. 58.

- ↑ Sean McMeekin: July 1914. Countdown to war. Basic Books, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-465-03145-0 , pp. 284 ff.

- ↑ Gerd Krumeich: July 1914. A balance sheet. Paderborn 1914, p. 151 ff.

- ↑ Kautsky Volume 2, p. 59 and p. 101.

- ^ Raymond Poidevin, Jacques Bariéty: France and Germany. The history of their relationships 1815–1975. Beck, Munich 1982, p. 288.

- ^ Janusz Piekałkiewicz : The First World War , 1988, licensed edition for Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 2004, p. 35, p. 44.

- ↑ Erwin Hölzle (ed.): Sources on the origin of the First World War. International documents 1901-1914. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1978, p. 490.