Chronology of the July crisis 1914

The chronology of the July crisis 1914 shows the decisions, discussions and correspondence of the decision-makers and important diplomats during the July crisis of 1914.

Departure Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria , heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary , and his wife Sophie Chotek of Chotkowa from the Town Hall in Sarajevo, five minutes before the assassination

26th calendar week

June 28th (Sunday)

- Assassination attempt in Sarajevo : assassination of Franz Ferdinand von Österreich-Este , heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary , and his wife Sophie Chotek von Chotkowa .

- Letter from the Austro-Hungarian state chief for Bosnia and Herzegovina Oskar Potiorek to Finance Minister Leon Biliński : "According to the previous surveys, it has been stated that the bomb thrower belongs to the Serbian socialist group that usually receives the slogan from Serbia"

27. Calendar week

June 29 (Monday)

- Conversation with the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold and Chief of Staff Franz Conrad (von Hötzendorf) : Conrad demands immediate steps, "[...] only violence can work". Berchtold saw the "moment to resolve the Serbian question" had come, but he wants to wait for the investigation and considers diplomatic preparations to be necessary.

June 30th (Tuesday)

- The German ambassador in Vienna, Heinrich von Tschirschky , reported to Berlin (arrival there July 2): “Count Berchtold told me today that everything indicates that the threads of the conspiracy to which the Archduke fell victim came together in Belgrade […] Here I often hear the request, even from more serious people, that the Serbs should be settled thoroughly. A number of demands have to be made to the Serbs, and if they do not accept them, tough action must be taken. I use every such occasion to be calm, but emphatic and serious about hasty steps. "

- The German Foreign Office ( Arthur Zimmermann ) gives the British and Russian ambassadors to understand that they want to avoid complications. The act of young anarchists cannot be attributed to the State of Serbia, but Serbia must contribute to the investigation.

July 1st (Wednesday)

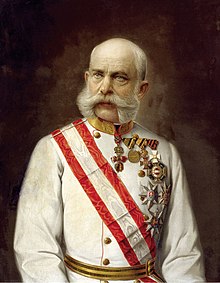

- Conversation with the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold and Chief of Staff Conrad: Berchtold informed Conrad that Emperor Franz Joseph I also wanted to wait for the investigation. The Prime Ministers Karl Stürgkh and István Tisza plead for restraint, Tisza is generally against war at this time (and writes this to Emperor Franz Joseph on the same day), Stürgkh wants to wait for the investigation. Conrad repeats that the “murder committed under the patronage of Serbia” was a reason for war. However, he agrees with Berchtold that Austria-Hungary's hands would be tied without Germany's backing.

- Interview with Alexander Hoyos and Victor Naumann : Naumann expresses his conviction that Germany would cover a war against Serbia.

July 2nd (Thursday)

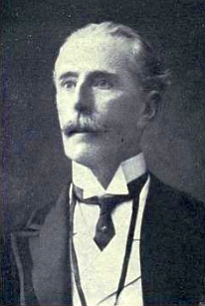

The German ambassador Heinrich von Tschirschky first urged prudence in Vienna, after a reprimand from Wilhelm II, he pushed for war

- Letter from Franz Joseph I to Wilhelm II : “The assassination attempt on my poor nephew is the direct result of the agitation carried out by the Russian and Serbian Pan-Slavists , whose sole aim is to weaken the Triple Alliance and to destroy my empire. According to all previous surveys in Sarajevo it was not a matter of the bloody act of an individual, but a well-organized plot, the threads of which reach Belgrade [...] After this recent terrible incident in Bosnia, you too will be convinced that a reconciliation of the Opposition that separates Serbia from us is no longer conceivable, and that the sustaining peace policy of all European monarchies will be threatened as long as this focus of criminal agitation in Belgrade continues undisturbed. "

- Talks between the German Ambassador Tschirschky with Emperor Franz Joseph and Foreign Minister Berchtold: Tschirschky urges prudence in both cases.

- The German Foreign Office speaks out against an Austro-Serbian war, as a world war could develop from it. German military circles, on the other hand, are in favor of general war, since the military situation is currently still comparatively favorable and will develop for the worse in the future. (see Council of War of December 8, 1912 ).

July 3rd (Friday)

- According to General Georg von Waldersee , the General Staff in Berlin was pleading for general war.

July 4th (Saturday)

- Undersecretary of State for Foreign Affairs Arthur Zimmermann warns Ladislaus von Szögyény-Marich (Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Berlin) to be careful not to make humiliating demands on Serbia.

- Wilhelm II returns Tschirschky's report from June 30 (see there) to the Reich Chancellor and the Foreign Office . Regarding Tschirschky's lecture, according to which the wish was expressed in Vienna that “the Serbs must be cleared up thoroughly”, the emperor noted: “now or never”. In response to Tschirschky's portrayal of warning against hasty steps in Vienna, Wilhelm II noted: “Who authorized him to do so? This is very stupid! Is nothing to do with him, since it is only Austria's business what he intends to do on this. Afterwards, if it goes wrong, it will be said that Germany did not want to! Tschirschky should kindly leave the nonsense! The Serbs must be cleared up and soon. ”- The imperial vote tipped the balance in favor of the military and against the political leadership, Tschirschky was reprimanded, and the Foreign Office immediately changed its position.

- A shop steward of the German Embassy and correspondent for the Frankfurter Zeitung speaks to the kuk "Press Department of the Foreign Ministry" and explains that Tschirschky now strongly recommends attacking Serbia as soon as possible (in contrast to his position a few days earlier).

- The French President Raymond Poincaré urges the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Nikolaus Szécsen von Temerin (Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Paris) to exercise restraint.

- The Imperial and Royal Legation Councilor Alexander Hoyos is sent to Berlin ( Mission Hoyos ).

July 5th (Sunday)

- Kuk ambassador Ladislaus von Szögyény-Marich hands Wilhelm II the memorandum of the kuk government and Franz Joseph's handwriting dated July 2 that Alexander Hoyos brought with him in the morning before a joint déjeuner (here: small lunch). The latter also briefly summarizes the thought processes of the memorandum (see above). Wilhelm reads both documents in the presence of Szögyény, initially reacts cautiously and cites possible serious European consequences that must be considered. After the déjeuner (around 1 p.m.), however, Wilhelm II authorized Szögyény to report to Franz Joseph that he could count on "Germany's full support" even in the event of European entanglements. He, Wilhelm II., However (constitutionally correct) had to hear the opinion of the Reich Chancellor, but did not doubt his approval. Action against Serbia, however, must be done quickly. Szögyény sends a corresponding telegram to Vienna at 7:35 p.m., which the kuk government receives at 10 p.m.

- General staff chief Franz Conrad (von Hötzendorf) has an audience with Franz Joseph, who agrees with Conrad's opinion: If Germany backs up against Russia, “then we will wage war against Serbia”.

- 5 p.m .: Wilhelm II orders Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , War Minister Erich von Falkenhayn , Adjutant General Hans von Plessen , Head of the Military Cabinet Moriz von Lyncker and Undersecretary Arthur Zimmermann to the New Palais , reads them the letters brought by the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Szögyény and questions Falkenhayn , "Whether the army is ready for any eventuality". Falkenhayn affirms this without reservation. The military plead for the fastest possible action against Serbia. When Falkenhayn asked whether preparations should be made, Wilhelm II replied in the negative. A separate conversation with naval officer Hans Zenker was similar .

- 6 p.m .: separate meeting with Wilhelm II. Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Arthur Zimmermann . According to Bethmann Hollweg's notes, the emperor declares: “But it is not our office to advise our ally what to do about the Serajevo bloody deed. Austria-Hungary must decide on this itself. We should abstain from direct suggestions and advice all the more since we would have to work with all means to prevent the Austro-Serbian dispute from developing into an international conflict. Emperor Franz Joseph, however, must know that we would not leave Austria-Hungary even in a serious hour. Our own interest in life requires the intact preservation of Austria. ”The Chancellor agrees without any reservations, thereby approving the imperial promises to Szögyény.

28th calendar week

July 6th (Monday)

- 3 p.m .: Conversation with Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Undersecretary Arthur Zimmermann with Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Ladislaus von Szögyény-Marich and Austro-Hungarian Legation Councilor Alexander Hoyos : Among other things, the Reich Chancellor submits that Austria-Hungary must decide what to do with Serbia . Regardless of its decision, Austria-Hungary could “definitely count on Germany as an ally and friend of the [kuk] monarchy”. Szögyény sends a telegram in Berlin at 5:10 p.m. with the corresponding report, which arrives in Vienna at 8 p.m.

- The German ambassador in London, Karl Max von Lichnowsky , indicated to the British Foreign Minister Edward Gray that Austria could take military action against Serbia.

July 7th (Tuesday)

- Meeting of the Joint Council of Ministers in Vienna, participants: Austro- Hungarian joint Minister of Foreign Affairs Leopold Berchtold , Austrian kk Prime Minister Karl Stürgkh , Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza , kuk Finance Minister Leon Biliński , kuk War Minister Alexander von Krobatin , kuk Chief of Staff Franz Conrad (von Hötzmiral) , kuk Konteradendorf Karl Kailer von Kaltenfels , Imperial and Royal Legation Councilor Alexander Hoyos : Berchtold asks the question “whether the moment has not come to make Serbia harmless forever by making an expression of force”, refers to the “unconditional support of Germany” and the German Recommendation to act as quickly as possible. Only the Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza opposes the immediate war: Serbia must first be given a diplomatic defeat. All other participants are of the opinion that "the current opportunity should be used for military action against Serbia". 16 days are estimated for one's own military mobilization. Berchtold sums up the result of the meeting that despite the dissenting opinion of Tisza, they had come closer, since Tisza's proposals “in all probability lead to the war-like conflict with Serbia that he [Berchtold] and the other members of the conference considered necessary will lead. "

July 8 (Wednesday)

- Vienna: The German Ambassador Tschirschky informed the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold with "great emphasis" that, according to a telegram from Wilhelm II, "an action by the [Austro-Hungarian] monarchy is expected against Serbia and that Germany would not understand if we did." let the given opportunity pass without struck ”. Berchtold forwards this to the Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza. Berchtold told Tschirschky that if Emperor Franz Joseph leaned towards Tisza's opinion, he would recommend that the Emperor “set up the demands in such a way that their acceptance seems impossible”.

- The Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza writes to Franz Joseph and warns of the consequences of a war: "An [...] attack on Serbia would, with all human foresight, evoke an intervention by Russia and thus a world war". Tisza recommends a "measured but not threatening note to Serbia, in which our concrete complaints should be listed and precisely Petita linked to them [...] Should Serbia give an inadequate answer or want to delay the matter, it would result in an ultimatum and to respond immediately after the end of the same by opening hostilities. "Then Austria-Hungary would have" shifted the guilt of the war on Serbia ", since" even after the Sarajevo atrocity it refused to honestly fulfill the duties of a decent neighbor. "

- The German ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky, informed Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg and State Secretary Jagow about the results of the Imperial and Royal Council of Ministers and Tisza's reservations.

- In his diary entries from July 7th and 8th, 1914, Kurt Riezler reproduces essential motives of the Reich leadership from the discussions with Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg: “Russia's military power is growing rapidly; with the strategic expansion of Poland the situation is untenable. Austria increasingly weaker and more immobile [...], at least unable to go to war as our ally for a German cause. The Entente knows that, as a result we are completely paralyzed […]. The Chancellor speaks of difficult decisions. Assassination of Franz Ferdinand . Official Serbia involved. Dispatch of Franz Josef to the emperor with inquiry about Casus Foederis . Our old dilemma with every Austrian Balkan action. When we talk, they say we pushed them into it; if we agree, it is said that we have let them down. Then they approach the Western powers whose arms are open, and we lose our last moderate ally [...]. Action against Serbia can lead to world war. The Chancellor expects a war, whatever its outcome, to transform everything that exists [...]. If the war comes from the east, so that we go to the field for Austria-Hungary and not for us, we have the prospect of winning it. If the war does not come, if the Tsar does not want to, or if dismayed France advises peace, we still have the prospect of disengaging the Entente through this action. "

July 9th (Thursday)

- Emperor Franz Joseph tends (according to the Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza) of the view that (initially) concrete demands should be made on Serbia. Foreign Minister Berchtold also sees advantages in such an approach, as it would avoid the "odium of a surprise surprise to Serbia, which would fall on the [kuk] monarchy, and would put Serbia in the wrong".

- The German Foreign Office in Vienna is urging that the "action against Serbia [should] be tackled without delay"

- Wilhelm II repeats the promise of support to Franz Joseph I ("even in the hours of seriousness [you will] find me and my kingdom loyal to your side in full harmony with our long-established friendship and our alliance obligations").

- Conversation with Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg with Vice Chancellor Clemens von Delbrück : In response to Delbrück's allegation that the current development would lead to war, Bethmann Hollweg replied that, in his and State Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow's opinion , the possible war could be "localized" (spatially limited).

- London: German Ambassador Lichnowsky's conversation with British Foreign Minister Edward Gray : Gray says that there are no secret agreements between Great Britain on the one hand and France and Russia on the other that would impose obligations on Great Britain in the event of a European war. However, there were intimate relations with the powers mentioned, there had also been "conversations" between the naval and military authorities on both sides since 1906, since it was believed at the time that Germany wanted to attack France. Incidentally, Gray is optimistic about the situation and is ready to have a calming effect on Saint Petersburg . "Of course, a great deal would depend [...] on the nature of the planned measures, and whether they aroused the Slavic feeling in a way that would make it impossible for Mr. Sasonov [(Russian Foreign Minister)] to remain passive".

July 10th (Friday)

- Vienna, conversation between Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold and the German Ambassador Tschirschky: According to Berchtold, the formulation of suitable conditions for Serbia is his main concern and he also wants to know Berlin's opinion on this (the Foreign Office rejects formulation aids on July 11, but does not formulate any reservations). The answer to the deadline must be kept short, even if this deadline is sufficient “to get instructions from Belgrade in Petersburg. Should the Serbs accept all the demands made, where would that be a solution that he [Berchtold] would be “very unsympathetic to, and he was still thinking about what demands could be made that would make acceptance completely impossible for Serbia”.

- Berlin, conversation between Vice Chancellor Delbrück and State Secretary Jagow, recording Delbrück: “From the conversation I got the impression that both statesmen [Bethmann Hollweg and Jagow] expected the possibility of armed entanglements between Austria and Serbia, but also believed a general European war to be able to prevent, and at least not intended to use the Austro-Serbian incident as an occasion for a preventive war ”.

- The German ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky, reports to Berlin the fundamental determination of Vienna and two of the later conditions (establishment of an imperial and royal investigative body in Belgrade, dissolution of associations and dismissal of some compromised officers) as well as the 48-hour deadline for the coming ultimatum to Serbia.

July 11 (Saturday)

- Vienna: The German Ambassador Tschirschky again calls on the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold to act quickly. Berchtold presents two of the conditions of the ultimatum (including those that would lead to the restriction of Serbian sovereignty). Further: "The deadline for answering the note would be as short as possible, maybe 48 hours. If the answer is not considered sufficient, the mobilization takes place immediately. ”They do not want to hand over the note while the French government is in Saint Petersburg , otherwise the common position could be discussed there. The note should be handed over either before President Poincaré leaves Paris or after his departure from St. Petersburg, on July 18 or 24. The latter date suggests that the harvesting work will be over by then, which will facilitate mobilization and reduce economic losses.

- State Secretary Jagow to Flotow (German Ambassador in Rome): Italy should not be informed for the time being.

July 12 (Sunday)

- Imperial and Royal Foreign Minister Berchtold to the Imperial and Royal Ambassador in Rome, Kajetan Mérey : The Italian government should not be inaugurated by the upcoming action against Serbia.

- Chief of Staff Conrad to Foreign Minister Berchtold: Opponents should not be alerted prematurely and prompted to take countermeasures, but after a demarche (de facto: ultimatum) the mobilization order should be given immediately.

- Ambassador Tschirschky's report on the 48-hour deadline and the content of two conditions arrives in Berlin (see July 11).

- First German efforts to localize the coming conflict: State Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow writes to the German ambassador in London, Karl Max von Lichnowsky , (draft of the instruction: July 7th): In the event of a war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Germany would like to “undermine all circumstances [a] localization of the conflict ”. Lichnowsky should influence the British press to see the assassination attempt as the "outflow of a political criminal morality incompatible with the cultural conscience of Europe" and to that extent Austria's military steps should be understandable. Care must be taken to avoid the appearance that Germany is inciting the Austrians to war. Lichnowsky replied on July 14th and 15th that he did not consider it possible to exert any influence and warned against illusions about the position of Great Britain.

- Report from the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Ladislaus von Szögyény-Marich to Foreign Minister Berchtold (from Berlin): “His Majesty Kaiser Wilhelm and all the other decisive factors here are not only firmly and nationally behind the [kuk] monarchy, but they also encourage us to the utmost insistence not to let the present moment slip by, but to take the most energetic action against Serbia and to clean up the revolutionary conspiratorial nest there once and for all, leaving it entirely up to us which means we consider to be right. "

29th calendar week

July 13 (Monday)

- Report of Section Councilor Friedrich von Wiesner to Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold: “Co-science of the Serbian government in the conduct of the attack or its preparation and provision of the weapons has not been proven or even suspected. Rather, there are indications that this is to be regarded as excluded. According to statements made by the accused, it was hardly contestable that the attack in Belgrade had been decided and prepared with the assistance of Serbian state officials Ciganović 'and Major Tankošic ', both of whom provided bombs, Brownings , ammunition and cyanide . […] On the basis of statements by the accused, there is hardly any doubt that Princip , Cabrinović, Grabes secretly smuggled bombs and weapons across the border into Bosnia by Serbian organs at the instigation of Ciganovic. This organized transport was led by border captains Schabatz and Losnica and carried out by financial guards, “whether or not the latter knew about the purpose of the transport could not be determined with certainty. Wiesner makes suggestions for the ultimatum, which are taken up (dismissal or criminal proceedings against those involved in Serbia, suppression of the involvement of Serb government organs in smuggling across the border).

- The German ambassador Tschirschky once again urged Vienna to hurry.

July 14th (Tuesday)

- Vienna: Meeting of Foreign Minister Berchtold, Austrian Prime Minister Stürgkh , Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza, Minister Burián : Agreement on the Note to Serbia: Note should be handed over on July 25, since Poincaré's visit to Petersburg will then be over [according to what was known at the time]. In the opinion of those present, a presentation during the Franco-Russian meeting would be seen as an affront and also enable an immediate agreement that would increase the likelihood of military intervention by Russia and France. Tisza gives up concerns about a short-term ultimatum, as Berchtold points to military difficulties if waiting too long. Berlin is advised that the postponement of the handover does not mean indecision, but only takes place in consideration of Poincaré's presence in St. Petersburg. Berchtold in his letter to Emperor Franz Joseph: “The content of the note to be sent to Belgrade today is such that the probability of a military conflict must be expected. However, if Serbia should give in anyway and comply with our demands, such a procedure by the kingdom would not only mean a deep humiliation of the same and pari passu [Latin: synonymous] with it, a loss of Russian prestige in the Balkans, but also certain guarantees for us the direction of the restriction of the great Serbian burial work on our soil. "

- The German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, warns Berlin against illusions about the British attitude: “It will be difficult to brand the entire Serbian nation as a people of villains and murderers [...] Rather, it can be assumed that the local sympathies will grow will turn to Serbianism immediately and in a lively manner as soon as Austria resorts to violence, and that the assassination of the [...] heir to the throne will only be used as a pretext [...] to harm the uncomfortable neighbor. The British sympathies, but especially those of the liberal party, have mostly turned to the nationality principle in Europe [...] and during the Balkan crises were usually aimed at the Slavs there ”.

July 15 (Wednesday)

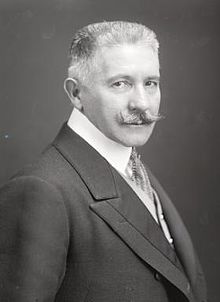

Gottlieb von Jagow, State Secretary in the Foreign Office and thus de facto Foreign Minister of the German Reich

- Ambassador Tschirschky's reports on the agreement in Vienna arrive in Berlin.

- State Secretary Jagow writes imploringly to the German Ambassador in London, Lichnowsky: “It is now an eminently political question, perhaps the last opportunity to inflict the death blow on the great inheritance under relatively favorable circumstances. If Austria misses this opportunity, its reputation will be lost and it will become an even weaker factor for our group . Since the Ew. Trans. [Lichnowsky] well-known intimate relations between England and Russia a different orientation of our politics seems impossible at the moment, it is of vital interest for us to maintain the world position of our Austrian ally. Ew. Trans. [Lichnowsky] is well aware of the importance of England's position in the event of any consequences of the conflict ”. State Secretary Jagow also writes to Albert Ballin with the request to use his contacts in England against further Anglo-Russian rapprochement.

- Letter from State Secretary Jagow to the German Ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky: “As austrophobic as Italian public opinion is in general, it has always been serbophilic [...] A collapse of the monarchy would also mean that Italy could win over some long-sought-after ones Open up parts of the country. It is therefore of the utmost importance that Vienna discusses the goals to be pursued in Serbia in the event of a conflict with the cabinet of Rome and keeps it on its side or - since the conflict with Serbia alone does not mean a casus foederis - strictly neutral. According to its agreements with Austria, every time there is a change in the Balkans in favor of the Danube Monarchy, Italy has a right to compensation [...] As I note in strict confidence, the only full compensation in Italy is likely to be the extraction of Trento [...] Ew. Exc. I ask [Tschirsky] to make Italy's position the subject of a detailed confidential consultation with Count Berchtold and possibly also to touch on the question of compensation. "

- The German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, repeats his warning from the previous day.

July 16 (Thursday)

- The British Foreign Minister Gray received the first hints about the demands on Serbia. "Germany should fully agree with this approach [...] Austria-Hungary would proceed in any case without considering the consequences."

- State Secretary Jagow regrets the delay in the ultimatum to Serbia to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador.

- The German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, in turn warns State Secretary Jagow and, in a long letter, Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg that "in the event of military measures against Serbia, entire public opinion [in Great Britain] will take a stand against Austria-Hungary". "The question for me [Lichnowsky] is whether it is advisable for us to support our comrades in a policy [...] that I see as an adventurous one [...]."

- Letter from Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to the State Secretary for the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine : “In the event of an Austro-Serbian conflict, the main thing is to isolate this dispute. We have reason to believe and we must wish that France, which is currently burdened with all sorts of worries, will do everything possible to prevent Russia from intervening. This task will be made much easier for the present rulers in Paris if the French nationalists do not receive any agitation material for exploitation in the next few weeks; I have therefore arranged in Berlin that all press polemics with France be stopped for the next few weeks if possible, and I would ask you to do the same in Strasbourg. It would also be advisable, for example, to postpone administrative measures planned there that could be taken up by agitation in France by a few weeks. If we succeed in not only keeping France quiet, but also in Petersburg to have a call for peace, this will have a very beneficial effect on the Franco-Russian alliance. "

- Schilling (Director of the Chancellery of the Russian Foreign Ministry) told the Italian Ambassador in Petersburg that Russia would not tolerate an attack against Serbia and asked that the Italian government let Vienna understand this.

July 17th (Friday)

- The handover date of the note has been brought forward from July 25th to July 23rd, to the day of the departure of the French government (President Raymond Poincaré , Prime Minister René Viviani and Pierre de Margerie from St. Petersburg).

- State Secretary Jagow to the German ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky: He should find out what Austria-Hungary is up to with Serbia without giving the impression that Berlin wants to get in the way or impose borders.

July 18 (Saturday)

- Austrian artillery will be provided with appropriate maps for the purpose of a possible bombardment of Belgrade.

- The note to Serbia is basically ready and, according to Legation Councilor Hoyos, "unacceptable".

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov expressed concern to the German Ambassador Friedrich Pourtalès regarding "powerful and dangerous influences [...] which did not shy away from the thought of plunging Austria into war, even at the risk of unleashing a general world fire [ …] One cannot blame a whole country for the acts of individuals […] The Vienna cabinet has not the slightest reason to complain about the attitude of the Serbian government, which rather behaves completely correctly […] in any case Austria is allowed to -Hungary, if it really wants to disturb the peace, do not forget that in this case it will have to reckon with Europe ”. According to Pourtalès' report, Sasanov also expressed his concerns to the Italian ambassador and said: “Russia would not be able to tolerate Austria-Hungary using a threatening language against Serbia or taking military measures.” Sasonov demands that in any case “be allowed from an ultimatum be out of the question ". Pourtalès reports on his conversation to Berlin on July 21st (receipt there: July 23rd).

- The Austro-Hungarian ambassador in St. Petersburg, Friedrich von Szápáry , vouched to the Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow for the peacefulness of the Austro-Hungarian government. Sazonov believes him.

July 19 (Sunday)

- Council of Ministers for Common Affairs of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy : Handover of the note on Thursday, July 23rd at 5 p.m., expiry of the 48-hour deadline on Saturday, July 25 at 5 p.m. The mobilization ordinance could then be issued in the night from Saturday to Sunday (July 26th). News about the intention of the note had already leaked, so any further delay should be avoided. This is decided unanimously. At the request of the Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza, the Council of Ministers unanimously decides to renounce the annexation .

- The German State Secretary Jagow asked Ambassador Tschirschky for the wording of the note.

- Wilhelm II orders the fleet to be held together until July 25th.

30. Calendar week

July 20 (Monday)

- The note goes to the imperial and royal ambassador Wladimir Giesl von Gieslingen in Belgrade as well as to the ambassadors in Berlin, Rome, Paris, London, St. Petersburg and Constantinople. The handover should now take place on July 23rd between 4pm and 5pm, the answer on July 25th at 6pm. The note is written in French.

- Arrival of the French government (President Raymond Poincaré , Prime Minister René Viviani and Director of the Foreign Ministry Pierre de Margerie ) for a state visit to St. Petersburg.

- The Serbian chargé d'affaires presented to State Secretary Jagow: Serbia wanted to improve relations with Austria-Hungary and also to counter attempts to endanger the peace and security of its neighbors. Demands for the prosecution of those complicit in the Sarajevo assassination attempt would be accommodated by Serbia, Serbia “would only be unable to meet demands that go against the dignity and independence of the Serbian state. The Serbian government asked us to act in Vienna in the spirit of forgiveness ”. Jagow replies that Serbia has so far done nothing to improve relations with Austria-Hungary, so that he can understand why more energetic strings are being pulled up there. The demands that Austria-Hungary wanted to make are not known to him.

- State Secretary Jagow once again asks the German ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky, to find out the content of the note and the exact time of its publication.

- London, Foreign Minister Gray to the British Ambassador in St. Petersburg, George William Buchanan : Austria and Russia should avoid difficulties in joint discussions. "If Austria's demands on Serbia are kept within reasonable limits and Austria can justify them, I hope that everything will be tried to prevent a breach of the peace."

July 21 (Tuesday)

- Emperor Franz Joseph approves the note to Serbia.

- Tschirschky receives the note and sends it to Berlin (receipt there on July 22nd in the afternoon).

- The New Free Press , "which played an outstanding leadership role in the press campaign against Serbia" (according to the British ambassador in Vienna Maurice de Bunsen ), publishes some of the demands of the note.

- The German Foreign Office does not believe in British intervention.

- Decree from Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to the ambassadors in Petersburg, Paris and London: The "center of action for the efforts that lead to the separation of the South Slavic provinces from the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and their unification with the Serbian kingdom [is] to be found in Belgrade [ ...], and there at least developed its activity with the connivance of members of the government and the army. […] In the meantime, under the eyes, at least with the tacit approval of official Serbia, the great Serbian propaganda has continued to grow in size and intensity; The latest crime, the threads of which lead to Belgrade, is to be put on their account. ”From this point of view, the procedure and the demands of Vienna should be viewed as moderate. However, it is to be feared that Serbia will not meet these demands. “If the Austro-Hungarian government does not want to finally renounce its position as a great power, then nothing else would be left than to enforce its demands on the Serbian government through strong pressure and, if necessary, by taking military measures The ambassadors should express themselves to the governments “in the above sense [...] and in particular express the opinion that the question at hand is only between Austria-Hungary and Serbia to be resolved Bringing matter to act, which to restrict to the two directly involved must be the serious pursuit of the powers. We urgently wish the conflict to be localized, because any intervention by another power as a result of the various alliance obligations would have unforeseeable consequences. "

- Berlin: State Secretary Jagow claims to the representatives of the Triple Entente Horace Rumbold , Arkadi Bronewski and Jules Cambon that he does not know the content of the note. Cambon reports this to Paris shortly after midnight (on July 22nd) and adds as follows: “I am all the more astonished about this when Germany is preparing to stand by Austria's side with particular energy. [...] I am assured that [...] the first preliminary warnings for mobilization in Germany have been issued. "

July 22nd (Wednesday)

- Berlin gets the message that Emperor Franz Joseph has "sanctioned" the note unchanged.

- The German Ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky, informs the Foreign Office (State Secretary Jagow): Instructions to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in Belgrade, Giesl, are to cancel if the answer is not satisfied.

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow to the Russian Ambassador in Vienna, Schebeko: Ambassador should issue a friendly but energetic warning to Vienna.

- The British Foreign Minister Gray recommends that the Russian Ambassador in London, Alexander Konstantinowitsch Benckendorff, hold a discussion in Vienna; the Austrian demands must be justified.

- The Foreign and Commonwealth Office rejects joint demarches by the Triple Entente in Vienna. According to Foreign Secretary Gray, the British position depends on whether the Austro-Hungarian demands are moderate.

July 23 (Thursday)

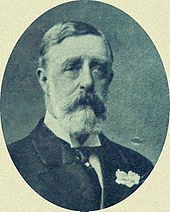

René Viviani, French Prime Minister ( President du Conseil )

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold specifies the language that it is not an ultimatum, but a demarche : “The […] term ultimatum for our demarche today in Belgrade is incorrect in that the deadline for breaking off diplomatic relations is not immediately followed by the entry into a state of war. "

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold to Ambassador Giesl in Belgrade: Postpone the handover of the “Demarche” to 6 p.m., as French President Poincaré will stay in Petersburg until 11 p.m. The news that the “demarche” has taken place is therefore not supposed to reach Petersburg that evening.

- The report of the German Ambassador Pourtalès from Petersburg arrives (see July 18).

- London 3 p.m.: The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador to London, Albert von Mensdorff-Pouilly-Dietrichstein , informs Foreign Minister Edward Gray informally of the note, Gray has concerns.

- State Secretary Jagow an Reichenau (envoy in Stockholm): In the event of a general war, Sweden should not stand aside either (against Russia).

- State Secretary Jagow continues to say that the Austrian demands are not known in Berlin.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to Wilhelm II: Immediate intervention by the Triple Entente in the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia is unlikely.

- The German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, warns Jagow and Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg of the illusion of being able to localize (spatially limit) the conflict.

- Discussion between the Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov and the French Prime Minister René Viviani : An attack on Serbian sovereignty will not be allowed. Viviani reports this to Paris early in the morning on July 24th (to Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin , representative of René Viviani as Prime Minister during his trip to St. Petersburg, arrival in Paris: July 24th, 5:30 a.m.).

- 6 pm: Handover of the “ultimatum” by Wladimir Giesl von Gieslingen to Deputy Prime Minister Pacu and General Secretary Gruic. (News of the successful handover will reach Vienna on July 24th, 2.15 a.m.)

- St. Petersburg 9 p.m .: The Italian ambassador reports that "Austria-Hungary is handing Serbia a completely unacceptable ultimatum on this day".

- Before he left Petersburg, the French Prime Minister René Viviani wrote a telegram to his representative Jean-Baptiste Bienvenu-Martin : Proposal for a demarche by the Entente in Vienna to advise Austria-Hungary to take moderate action against Serbia.

- St. Petersburg 10 p.m .: Departure of the French government (President Raymond Poincaré , Prime Minister René Viviani and Political Director of the Foreign Ministry Pierre de Margerie ).

July 24th (Friday)

- 10 a.m .: Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow is informed by the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador about the content of the ultimatum to Serbia, Sasonow comments on this and others. a .: "Vous mettez le feu à l'Éurope ... C'est que vous voulez la guerre et vous avez brulé vos ponts" ("You are setting Europe on fire! ... You want war and have broken the bridges behind you") .

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold claims to Russian Chargé d'Affaires Kudaschew that they do not want to humiliate Serbia.

- 12.30 p.m .: Exchange of views between the Russian Foreign Minister and the British, French and Romanian ambassadors. The French ambassador Maurice Paléologue pledges French support to Russia.

- 3 p.m., St. Petersburg local time: meeting of the Russian Council of Ministers. Encouraged by the results of the talks during the French government visit, the Russian Council of Ministers decided to support Serbia and, if necessary, initiate mobilization. Foreign Minister Sasonow said that “Germany has been making systematic preparations for a long time” to increase its power and influence, that the Austrian ultimatum was drafted “with German, tacit consent”, and that its acceptance would degrade Belgrade to a protectorate of the Central Powers. If Russia gave up "its historical mission" to guarantee the independence of the Slavic peoples, it would "gamble away all its authority", lose its "prestige in the Balkans" and be degraded to a secondary power. The Council of Ministers agrees with this point of view and resolves: 1. joint presentation in Vienna to extend the deadline, 2. Serbia should not defend itself, but appeal to powers, 3. the Tsar should be recommended to partially mobilize (districts Kiev, Odessa, Moscow and Kazan as well as Baltic and Black Sea Fleet). The Tsar agrees a little later.

- The Foreign Office of the German Reich, in turn, issued the language rule to all embassies, stating that Berlin was not aware of the grade and had no influence on it.

- 2 p.m .: The Austrian note to Serbia is announced to the British Foreign Minister Edward Gray . Gray expresses concerns about point 5 and fears repercussions for European peace.

- 3/4 p.m .: Serbian mobilization. Due to the military balance of power, the exposed location of the capital and the small size of the country, this can be interpreted as defensive.

- The German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Jagow, told the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador that he was "naturally quite in agreement" with the note

- The German press overwhelmingly welcomes the note, the French condemn it.

- The British Chargé d'Affaires Horace Rumbold and the French Ambassador Jules Cambon in Berlin agree that some demands, namely points 5 and 6, "an independent state [...] can only accept with difficulty". Cambon expressed the opinion that it was probably no coincidence “that the note was presented in Belgrade at the moment when the French President left St. Petersburg. A discussion between Mr Viviani and Mr Sasonow is now ruled out. ”Rumbold sends a corresponding report to Edward Gray, who receives it on July 27th and notes on July 29th:“ Mr von Tschirschky was apparently another link in the chain the encouragement given to Austria to proceed without any consideration ”.

- 7 p.m., St. Petersburg: The German Ambassador Pourtalès reads Bethmann Hollweg's note to Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow (see July 21). Sasonov remarks, among other things, that Russia will not tolerate Austria-Hungary swallowing Serbia, in which case Russia will wage war with Austria-Hungary.

- The German note (see July 21) will also be announced in Paris and London.

- 7.45pm: 1st British mediation proposal. Germany, France, Italy and England should work towards moderation in Vienna and St. Petersburg. Above all, Berlin should hold back Vienna.

- Midnight, Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Conrad to Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold: Serbia proclaimed mobilization on July 24th at 4pm, this requires immediate mobilization in Austria-Hungary (on July 25th).

July 25 (Saturday)

July 25, 1914, shortly before 6 p.m .: The Serbian Prime Minister Nikola Pašić hands over the response of the Serbian government to the Austrian ambassador

- Morning: Telegram from Saint Petersburg to Belgrade with protection guarantee. The corresponding telegram arrived in Belgrade on July 25 at 11:30 a.m., in good time before the Serbian answer to the ultimatum was formulated (however, the influence on the answer is disputed today). “In their response to the individual charges, the authors found a subtle mix of approval, conditional approval, excuses and rejections [...] Point 6 (on the participation of Austrian officials in the prosecution of suspects) was flatly rejected on the grounds that he was against the violates the Serbian constitution. "

- Morning: State Secretary Jagow gives Theodor Wolff information on the political intentions of the Foreign Office. Jagow found Wolff's opinion of the Austrian ultimatum to be unsuitable, but one had to remain firm now. He does not see the danger of a world war, he believes that Russia will withdraw, “the diplomatic situation is very favorable. Neither Russia, France, nor England wanted war. And if it had to be (smiling) - one day the war would come after all, if we let things go, and in two years Russia would be stronger than now ”. He does not consider the situation to be critical. Wilhelm von Stumm took the same position vis-à-vis Wolff, and also said that in the event of a conflict, “you will find your way back. Like Jagow, he says that if we do not get out of this situation now, war will be inevitable in two years' time. The point is to determine whether Austria is still worth something with us as an ally [...] France cannot want a war. Such a good situation won't come back. Just perseverance and strength! "

- The German Foreign Office (State Secretary Jagow) is pushing for an immediate declaration of war to prevent “interference” and to face the world with “ fait accompli ”. The Federal Foreign Office and Jagow refuse to extend deadlines. At the same time he telegraphed the German ambassador in London that a mediation between Russia and Austria-Hungary might be attempted on the German side. A British mediation proposal is sent without reprint to the German ambassador in Vienna.

- In Russia, troop exercises are canceled, the regiments return to the barracks.

- 11 a.m.: The Russian Privy Council sanctions the decisions of the Council of Ministers. Message from the Russian government: Russia cannot remain indifferent.

- 3 p.m., St. Petersburg: the French ambassador assures Foreign Minister Sasonov the unconditional support of France, the British ambassador evades.

- Wilhelm II orders the return of the fleet against the advice of the Reich Chancellor.

- In the European states of the Entente , doubts are growing as to whether the weak partner Austria-Hungary is the driving force behind the events, as, for example, the German ambassador Wilhelm von Schoen reported from Paris on July 28th. The French press condemns the ultimatum.

- The urgent request by Russia and Great Britain to extend the deadline for the ultimatum to Serbia is rejected by Berchtold.

- 2. British mediation proposal: four mediation after mobilization of Austria-Hungary and Russia. There are growing doubts about the localization. The Austro-Hungarian ambassador in London claims that the note is not an ultimatum and that no immediate military steps are planned by Austria-Hungary.

- Prime Minister Nikola Pašić personally handed the answer to the Austrian embassy five minutes before the deadline (July 25, 5:55 p.m.). Ambassador Giesl scanned the text and left immediately (6:30 p.m.) with the entire embassy staff. Breakdown of diplomatic relations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, Austrian partial mobilization.

July 26th (Sunday)

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold gives the missions in Berlin, London, Rome and Paris the language rules for breaking off relations with Serbia, in which the war is also announced. The main reason given is: “The royal Serbian government has refused to fulfill the demands that we had to make of it in order to permanently secure our vital interests threatened by it, and thus stated that it is unwilling to accept its subversive ones to abandon the constant alarm of some of our border countries and their eventual separation from the structure of the monarchy ”.

- Berlin calls on Vienna to carry out military operations and a declaration of war as quickly as possible; Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff Conrad does not think this is possible until August 12th.

- The German chief of staff, Moltke, hands over the sommelier he has formulated to Belgium to the Foreign Office. It is claimed that French troops want to attack Germany via Belgium, but that Belgium cannot prevent this: “It is a requirement of self-preservation for Germany to forestall the enemy attack. It would therefore fill the German government with the greatest regret if Belgium saw an act of hostility in the fact that the measures of its opponents would force Germany to enter Belgian territory to defend itself [...] Should Belgium be hostile to the German troops [...] Germany will, to its regret, be forced to regard the kingdom as an enemy. "

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to Ambassador Pourtalès (St. Petersburg): Russia should be satisfied with Austria's renunciation of annexation and not endanger European peace.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to Ambassador Pourtalès: "Preparatory military measures by Russia" would force German mobilization and that would mean war.

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow asks the German Ambassador Pourtalès and instructs the Russian Ambassador in Rome, Kurpenski, that Germany and Italy should have a moderating effect in Vienna, because: “For Russia, however, the balance in the Balkans is a vital question and Serbia could therefore be suppressed impossible to tolerate a vassal state of Austria ”. Apart from that, such a war cannot be localized.

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow explains to Friedrich von Szápáry (Austro-Hungarian Ambassador to St. Petersburg) that points 5 and 6 of the ultimatum are unacceptable.

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov calls on the British Ambassador Buchanan that England declare itself now.

- European envoys report from St. Petersburg that war preparations are clearly in progress in Russia.

- Paris, conversation between Philippe Berthelot (Deputy Director in the French Foreign Ministry) with Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Szécsen: Berthelot's astonishment at the rejection of the Serbian answer.

- Paris 5 p.m., conversation between Bienvenu-Martin (representative of the French Prime Minister) with the German Ambassador Schoen: Austria's renunciation of annexation is put forward.

- Paris 7 p.m., conversation between Berthelot (Deputy Director in the French Foreign Ministry) and the German Ambassador Schoen. France would be ready to act calmly if Berlin advised Vienna to moderate. Schoen tries to come up with a joint communiqué. Barthelot sums up the prevailing impression of the Entente that “Germany's attitude is incomprehensible to anyone who is overly concerned if it is not aimed at war [...] With the repeated assurances that Germany did not know the content of the Austrian note, it is not more allows to cast doubt on this point. But is it likely that Germany should have stood by Austria's side in such an adventure with her eyes closed? Does the psychology of all past relations between Vienna and Berlin permit the assumption that Austria would have taken a position without reservation of retreat had it not first considered all the consequences of its intransigence with its ally? How surprising is Germany's refusal to propose mediation in Vienna, now that it knows the unusual wording of the Austrian note! What responsibility would the German government assume and what suspicion would weigh on it if it persisted in standing between Austria and the Powers after the so to speak unconditional submission of Serbia, now that the slightest advice given to it in Vienna was the nightmare on Europe would put an end to it! "

- London: The British Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs Arthur Nicolson explains to the Russian Ambassador Benckendorff that England is still hesitant, to the French Chargé d'affaires Fleuriau that England will not remain neutral in a war against France.

- London: Undersecretary Nicolson recommends Foreign Minister Gray take up Sasonov's conference proposal.

- 3. British mediation proposal. Foreign Minister Gray to missions : Inquiry as to whether there is readiness for an ambassadors' conference, corresponding inquiry to the German Ambassador Lichnowsky.

31st calendar week

July 27 (Monday)

- Vienna: Decision to declare war on Serbia “mainly to remove the ground from any attempted intervention”.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg informed Schoen (German ambassador in Paris) that Germany might mediate between Vienna and Petersburg, but not between Vienna and Belgrade, since the Austro-Serbian conflict only affects these two states.

- State Secretary Jagow informed the British and French ambassadors that Germany was against a conference of the great powers, the Chancellor announced the same to the German ambassador in London.

- State Secretary Jagow expresses his regret to the Austrian ambassador about the delay in military operations (since Austria cannot mobilize until August 12).

- State Secretary Jagow explains to the French Ambassador Jules Cambon that the diplomatic intervention suggested by London only has a chance of success "if events do not precipitate".

- Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov telegraphed his missions in Paris, London, Vienna, Rome, Constantinople and Berlin that the Serbian response was very accommodating.

- Bienvenu-Martin (representative of the French head of government) expressed his astonishment to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Szécsen at the rejection of the Serbian answer, “Austria-Hungary would take on a terrible responsibility if, after Serbia had given in so much, they would unite because of the remaining small differences World War would cause ". To the British ambassador Bertie he declares himself ready for the conference of four in London. He expressed his suspicion to the Russian ambassador Alexander Petrovich Iswolski that Germany wanted to separate France and Russia through the crisis and that Austria-Hungary, not Russia, was a threat to peace.

- Viviani (French head of government) to Paléologue (French ambassador in St. Petersburg): France is ready to keep peace with Russia.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg claims to the German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, that he immediately forwarded the mediation to Vienna, but shortly thereafter rejects mediation between Vienna and Belgrade.

- Berlin, the language regulation for the outbreak of war is being drafted: The conflict is only concern of Serbia and Austria, German efforts are continuously directed towards localization. Should Russia, however, take sides with Serbia, “the casus foederis is given for Germany and a general conflict [a (area) fire] is inevitable. The question of maintaining peace depends on Russia. "

- The French ambassador Jules Cambon in Berlin warned Paris: “It was always intended that, should Germany have to wage a conflict against West and East, we [France] would be the first target of its armies [...] I am concerned about it, how little goodwill Wilhelmstrasse shows in supporting English efforts. Whatever the [Reichs] Chancellor may say, the power of the institutions and the military spirit is so great here that we have to be ready ”.

- London, Eyre Crowe Memorandum : Great Britain must intervene.

- The British Foreign Minister Gray indicated to the German and Austrian ambassadors that Austria-Hungary should be satisfied with the Serbian answer. Gray made it clear to the Austro-Hungarian and Russian ambassadors that England would not be unconditionally neutral. He describes the German mediation as ineffective, since the German government is obviously content with "just passing on" Grey's tips and suggestions. Gray also made the following comments to the German ambassador on the same day (quoted according to the transmission to Berlin): The wording of the Serbian answer to the ultimatum “shows that Serbia has complied with the Austrian demands to an extent that he has never done thought it possible […] If Austria were not satisfied with this answer, or if Vienna did not consider this answer as a basis for peaceful negotiations, or if Vienna even proceeded to occupy Belgrade […] it was perfectly clear that Austria just looking for an excuse to crush Serbia. In Serbia, however, Russia should then be hit and Russian influence in the Balkans. It is clear that Russia cannot look on indifferently and must see it as a direct challenge. This would lead to the most terrible war that Europe had ever seen, and no one knew where such a war could lead. ”Gray made a similar statement in the House of Commons .

- Both the French ambassador in Berlin (towards State Secretary Jagow) and Foreign Minister Gray in London (towards the German ambassador Lichnowsky) point out that the local conflict between Austria and Serbia is inextricably linked to a European conflict, and localization is not possible. The French ambassador asks Jagow directly whether Germany wants war, which Jagow denies.

July 28th (Tuesday)

- Berlin, 10 a.m .: After reading the Serbian reply, Wilhelm II declares several times that this eliminates any reason for war and proposes the occupation of Belgrade as a guarantee for the execution of the promises.

- 11 a.m.: Austria-Hungary declares war on Serbia. In Bad Ischl, Emperor Franz Joseph signs the declaration of war by the Austro-Hungarian monarchy on the Kingdom of Serbia , which the German government had massively urged the ally to speak out immediately since July 25th.

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchthold explains that the Serbian concession is only an apparent one and that there will be no negotiations on the note. The British conference proposal was overtaken by the state of war, the British step came too late, and there would be no Austro-Hungarian relenting.

- Berlin: On the recommendation of the Chancellor (to "put Russia's guilt in the brightest light"), Wilhelm II begins an exchange of telegrams with the Tsar and appeals to him for the solidarity of the monarchies. Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg also instructed the German ambassador Pourtalès that Russia should be content with the declared renunciation of Austria-Hungary's annexation , the ambassador in London that Vienna could not be forced to give in, but that Germany could not reject the British proposal a limine for tactical reasons (the latter already formulated on July 27, 11:50 p.m.).

- St. Petersburg: The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow explains to the German Ambassador Pourtalès that Austria will show the will to go to war if it refuses the Serbian answer, to the Russian Ambassador in London (Benckendorff) that Germany will favor rather than mediate Austria's irreconcilability, to the British Ambassador Buchanan: If Austria crosses the border with Serbia, the Russian mobilization takes place. He means to the Austrian ambassador that the renunciation of annexation is not impressive, to Benckendorff that the key to the situation lies in Berlin. He also announced that four military districts will be mobilized on July 29th. Paléologue confirms to Sasonov that France is ready to fulfill its alliance obligations.

- In Paris the motto is that the best way to avoid a general war is to avoid a local one. Viviani to Bienvenu-Martin: French influence on Russia only possible if Berlin seriously mediates in Vienna

- Berlin 6:39 p.m.: The news of Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia arrives.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg instructed the embassies in St. Petersburg, Vienna, London and Paris that the declaration of war would not change the German efforts to “induce Vienna to open an open discussion with Petersburg with the aim of determining the purpose and scope of the Austrian approach in Serbia to clarify in an incontestable and hopefully satisfactory way for Russia. "

- Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg to the German Ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky: “The answer now available from the Serbian government to the Austrian ultimatum shows that Serbia has complied with the Austrian demands to such an extent that the Austro-Hungarian one with a completely intransigent attitude Government can be expected to gradually turn away from it in public opinion across Europe. According to the information provided by the Austrian General Staff, active military action against Serbia will only be possible on August 12th. The k. As a result, the [German] government finds itself in the extraordinarily difficult position that it remains exposed to the mediation and conference proposals of the other cabinets in the meantime, and if it continues to hold on to its previous reluctance to face such proposals, the odium of having caused a world war, finally falls back on them in the eyes of the German people. A successful war on three fronts cannot be initiated and waged on such a basis. It is imperative that responsibility for a possible spillover of the conflict falls on those not directly involved in any circumstances ”. Vienna should make a declaration that in order to meet the demands and to create guarantees, there should only be a temporary occupation of Belgrade and other parts of Serbia. Tschirschky should accordingly with ku, k. Foreign Minister Berchthold will speak, but: “You will have to carefully avoid giving the impression that we want to hold back Austria. It is only a matter of finding a mode that enables the realization of the goal pursued by Austria-Hungarians, to put an end to the great Serbian propaganda, without at the same time unleashing a world war, and if this cannot be avoided, the conditions under which he is to be led to improve for us as far as possible. ".

- The Chancellor informed the British Ambassador Goschen that the conference would be rejected because an "Areopagus" over Austria could not be accepted. The decision about war and peace lies with Russia, not Germany

- Fourth British mediation proposal: the German government itself should propose procedures for mediation, the French ambassador in Berlin, Jules Cambon, made a similar statement.

July 29th (Wednesday)

- Shortly after 2 o'clock in the morning: Belgrade was bombarded by the river monitors SMS Temes , Bodrog and Számos .

- St. Petersburg 11 a.m. local time: notification of Russian partial mobilization, which, according to Sasonov, should not be equated with war as in Western European countries.

- During the morning: the bombardment of Belgrade became known in Europe.

- Kuk Foreign Minister Berchtold refuses to talk to the Russian Ambassador Schebeko about Serbia, to the German Ambassador Tschirschky negotiating the ultimatum and calls on Germany to threaten Russia with general mobilization and declares to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in London, Mensdorff, that one being pushed by no one.

- The German Ambassador Tschirschky brought the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold - as requested: without emphasis - the “stop in Belgrade” proposal, but Berchtold was not prepared to answer.

- 12:50 p.m.: Berlin issues warnings to Paris and Petersburg

- The German State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Jagow sends the German Ambassador in Brussels, Claus von Below-Saleske , the “Sommation” (the ultimatum) to Belgium.

- 10:30 p.m.: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg now urges the German ambassador in Vienna, Tschirschky, to hurry about the “stop in Belgrade proposal”, and to Pourtalès (11:05 p.m.) he demands that Russia renounce Austria's annexation - Satisfy Hungary and wait for German mediation to take effect.

- Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg informed the British Ambassador Edward Goschen that Germany would attack France in breach of Belgian neutrality and that in order to achieve British neutrality, the restoration of the territorial integrity of France and Belgium - but not that of their colonies - would be offered after the war. Goschen immediately reported this to London, where Eyre Crowe added: "These astonishing proposals require only one comment, that they cast a bad light on the statesman who makes them."

- London, 5:30 p.m .: Foreign Minister Gray gives the German ambassador a serious warning, which is also presented to the Kaiser for information: Great Britain would not be able to stand aside in a war with German and French participation and “ if war breaks out, it will be the greatest catastrophe the world have ever seen ”(“ when war breaks out, it will be the greatest catastrophe the world has ever seen ”).

- Probably because of the reactions of the British, the Chancellor now instructs Tschirschky (sometimes shortly before, sometimes after midnight) that Vienna should resume negotiations with Petersburg and respond to the British proposal.

- The Chancellor announced to St. Petersburg that he refused to involve the Hague Arbitration Court , that Russia should abstain from any hostility towards Austria, otherwise he could not mediate.

- Gray called on Germany to mediate (or “make some kind of proposal”) and declared that there could be no British neutrality in a continental war, but he also had reservations about the French ambassador. The "Halt-in-Belgrade" proposal is propagated as the basis for a mediation (5th British mediation suggestion), but in any case mediation cannot exist in the manner desired by Germany, “that Russia is urged to stand idly by while Austria would be given a free hand to go as far as you want ”. However, the UK cabinet meeting has not yet been decided.

- Around 7 p.m. St. Petersburg local time: Ambassador Pourtalès brings the German warning to Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov: Further Russian mobilization measures are forcing Germany to mobilize, which in turn means war.

- St. Petersburg: after 7 p.m. local time the decision for general mobilization is made, at 9:40 p.m. the telegram from Wilhelm II arrives, who expresses his opinion “that it would be entirely possible for Russia to participate in the Austro-Serbian conflict to remain in the role of the spectator without embroiling Europe in the most appalling war it has ever seen [...] Of course, military measures on the part of Russia, which Austria would see as a threat, would accelerate a disaster that we both wish to avoid, and endanger my position as a mediator, which I willingly accepted at your appeal to my friendship and my assistance ”.

- 5 to 7 p.m .: Council of Ministers in Paris: Agreement with Russia.

- 5:30 p.m. Paris: Ambassador Schoen brings the German warning to French Prime Minister Viviani.

- At 11 p.m. the tsar ordered the suspension of the general mobilization decided four hours earlier and the conversion to partial mobilization.

July 30th (Thursday)

- St. Petersburg, around 1 a.m. 1. Sasonow's formula to Pourtalès (mediation proposal to Germany): “If Austria, in recognition of the fact that its dispute with Serbia has taken on the character of a question of European interest, agrees to remove from its ultimatum the points which the If Serbia's sovereign rights are violated, Russia undertakes to stop all military preparations ”. (The proposal will not be pursued further in Berlin).

- Vienna: Berchtold rejects negotiations with the German ambassador about the Serbian-Austrian conflict, the "Halt-in-Belgrade" proposal will only approach Austria-Hungary after the war and to enforce the peace conditions. Speaking to the Russian ambassador, he declares that he is ready to negotiate with Russia. Almost at the same time, Emperor Franz Joseph I, Foreign Minister Berchtold, Chief of Staff Conrad and War Minister Krobatin are discussing whether the war against Serbia should be continued, the English proposal delayed and the general mobilization carried out on August 1st.

- Berlin, afternoon: Jagow informs the Austro-Hungarian ambassador about the British government's "Halt-in-Belgrade" proposal, but admits military satisfaction and the occupation of Serbia.

- Berlin, afternoon: The false report of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger , which reported with the headline “The decision has been made!” About a German mobilization allegedly ordered by Kaiser Wilhelm II in response to the Russian partial mobilization, causes irritation despite a denial by Jagows in public and diplomacy.

- Berlin around 9 p.m .: The German military is pushing for war at Bethmann Hollweg, the declaration of the imminent danger of war should be made the next day if possible, Bethmann Hollweg promises to do so.

- The German chief of staff, Moltke, told the “Kundschafstbureau” of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff in Berlin: “In contrast to the usual Russian mobilizations and demobilizations, Germany's mobilization would necessarily lead to war.”

- Berlin now expects Britain to enter the war in the event of a continental war.

- Germany rejects 1. Sasonow's formula.

- Jagow claims to the French ambassador Cambon that the Russian mobilization calls into question German mediation.

- The Chancellor instructed the German Ambassador Tschirschky that Vienna should respond to Grey's proposals, otherwise it would hardly be possible to “blame Russia for the outbreak of the European conflict.”

- Jagow instructs the German ambassador in London, Lichnowsky, that Gray should influence Petersburg to stop the war measures.

- St. Petersburg, 3 p.m. local time: Sasonov reaches the Tsar to give the order for general mobilization, which is immediately communicated to the General Staff by telephone. The decision had been made the day before at 7 p.m., but was then reduced to partial mobilization by the tsar at 11 p.m.

- Gray again suggests "Halt-in-Belgrade", also Buchanan. At the same time, inquiries whether a change in Sasonov's formula is still possible. (6th English mediation proposal)

- The French President Poincaré informed the British Ambassador Bertie (from him passed on to the British Foreign Minister Gray) that only Great Britain's clear statement could prevent the war.

- Paris 11.25 p.m.: Message from the French ambassador in St. Petersburg, Paléologues, about the first Russian measures for general mobilization arrives in Paris. According to Paléologue, Sasonow and the Tsar have the impression "that Germany does not want to speak the decisive words in Vienna that would secure peace."

July 31 (Friday)

- Morning: Russian general mobilization published.

- The Russian Foreign Minister Sasonov in turn calls on Pourtalès that Germany should act moderately on Vienna.

- Ambassador Goschen rejects a British promise of neutrality to Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg.

- 11 a.m. local time St. Petersburg, Privy Council: Sasonov tries to win Romania as an ally and passes on Sasonov's second formula to the missions (embassies) (Russia's wait-and-see attitude and examination of adequate satisfaction, but without affecting the sovereignty and independence of Serbia, provided Austria not previously invaded Serbia). He advises the British ambassador to negotiate in London.

- According to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold, the Austro-Hungarian renunciation of annexation only applies to a localized war.

- The Austro-Hungarian Council of Ministers rejects a conference of the great powers, but conditionally accepts the 6th British mediation proposal.

- According to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Berchtold, the starting point of all discussions could only be a “lesson” for Serbia.

- 12 noon Berlin: Russian general mobilization is reported.

- 1 p.m. Berlin “State of imminent danger of war” is ordered.

- The German Foreign Office asks the Admiral Staff whether an attack on the British fleet is possible.

- 2:55 p.m. St. Peterburg local time, telegram from Nikolaus II to Wilhelm II (entrance Berlin 2:52 p.m.): “It is technically impossible to stop our military preparations which were necessary as a result of Austria's mobilization. Far be it from us to wish for war. As long as negotiations with Austria over Serbia continue, my troops will not take any challenging action. I give you my solemn word on it. "

- 2:04 p.m. Berlin, telegram Wilhelm II to Nikolaus II: "I have now received reliable information about serious preparations for war on my eastern border. The responsibility for the security of my empire forces me to take preventive defense measures [...] You can still maintain the peace of Europe if Russia agrees to stop the military measures that Germany and Austria-Hungary must threaten ”.

- In the British cabinet meeting there is still no determination of what to do in the event of a European war. Foreign Minister Gray informed the Russian Ambassador Benckendorff that Great Britain could not remain neutral in a general war, but the French Ambassador Cambon that Great Britain could not commit itself yet. An ultimatum to France could justify an intervention.

- The British Foreign Minister Gray informed the British ambassador in Berlin, Goschen, that a four-power conference would guarantee Austria-Hungary satisfaction (7th British mediation proposal).

- Gray asks the British ambassadors Berti (Paris) and Goschen (Berlin) whether France and Germany want to maintain Belgian neutrality and calls on the British ambassador in Brussels, Villiers, that Belgium should defend it.

- Nicolson tells Gray that he thinks it is necessary to mobilize the army, while Crowe expresses his opinion to Gray that Great Britain must intervene or renounce its status as a great power.

- In the afternoon, Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg sent Ambassador Tschirschky to Vienna to demand that Austria-Hungary should immediately take part in the war against Russia. Reason: "After the total Russian mobilization, we have decreed the threat of war, which is expected to be followed by mobilization within 48 hours. This inevitably means war. "

- State Secretary Jagow informed the French and English ambassadors that the Russian rush and general mobilization were responsible for the escalation.

- 3 p.m. Berlin: Consultation with Wilhelm II, Chief of Staff Moltke and Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg: the ultimatum to Russia is approved and forwarded to Russia at 3:30 p.m. At the same time, a request for neutrality is sent to France. The Reich Chancellor lays down the language according to which the German general mobilization must be seen as a consequence of the Russian. Wilhelm II writes to Franz Joseph that Serbia is now of secondary importance, one must mobilize all forces against Russia and win Italy's support.

- State Secretary Jagow explains to the British Ambassador Goschen that Germany cannot reply to the recent British mediation proposal before the Russian reply to the ultimatum and that consultation with Wilhelm II and the Reich Chancellor must be made.

- Conversation between the Russian Foreign Minister Sasonow and the British Ambassador Buchanan and his French colleague Paléologue, determination of the 2nd Sasonow formula (Russia's wait-and-see attitude and the great powers' examination of the satisfaction due to Austria-Hungary if Austria-Hungary does not invade Serbia).

- 7 pm Paris: the German ambassador Schoen presents the French Prime Minister Viviani with the 18-hour “request” as to whether France will remain neutral in a Russian-German war.

- The French Prime Minister Viviani asks the British Ambassador Bertie about the position of his government, Joseph Joffre (Commander of the French Army) demands immediate French mobilization

- The French President Poincaré asked the British King George V that Great Britain should explain itself.

- 10:30 p.m .: the British ambassador Bertie asks the French Prime Minister Viviani about the respect of Belgian neutrality by France.

- St. Petersburg, midnight: Pourtalès hands Sasonov the German ultimatum: German mobilization if Russia does not "cease all war measures against us [Germany] and Austria-Hungary within 12 hours and make certain statements about this". German mobilization inevitably meant war. At the handover, Sasonov replied that the Russian general mobilization could no longer be withdrawn; without an agreement with Austria-Hungary, peace could not be maintained.

- 11:00 p.m .: Bertholet (Deputy Director in the French Foreign Ministry) explains to the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador Szécsen that Serbia has taken a back seat due to the German "inquiry".

- French War Minister Messimy informed Russian Ambassador Isvolsky that France was determined to go to war and asked him to “confirm the hope of the French General Staff that all our efforts will be directed against Germany and that Austria regards it as a quantité negligeable [irrelevance] will be".

- Margerie (Political Director at the French Foreign Ministry) informed the British Ambassador Bertie that France would maintain Belgian neutrality.

August 1st (Saturday)

- Paris 8 a.m.: Joseph Joffre again calls for French general mobilization. The impression that Germany wants war is growing in Paris. Language regulation to the missions (embassies) that the decision lies with Germany.

- Paris 9 a.m. to 1 p.m .: Council of Ministers, alliance commitment reaffirmed, mobilization set for 4 p.m.

- Franz Joseph to Wilhelm II. "As soon as my general staff learned that you are determined to start the war against Russia immediately and carry it out with all your might, the decision was made here too to assemble the predominant main forces against Russia."

- Berlin: Jagow and Zimmermann (Foreign Office) blame the British Ambassador Goschen Russia for the escalation.

- St. Petersburg 12 noon (local time): German ultimatum expires.

- Nikolaus II. To Wilhelm II .: Wants a German guarantee that mobilization is not identical with war: “I understand that you are forced to mobilize, but I want you to receive the same guarantee as I gave you, that these measures do not mean war and that we will continue to negotiate ”In the answer of the same day, Wilhelm II does not give this guarantee and demands that Russia withdraw the mobilization without consideration.

- Paris 3:55 p.m .: French general mobilization ordered.

Head of the Military Cabinet Moriz von Lyncker

Head of the Navy Cabinet Georg Alexander von Müller

- Berlin 5 p.m .: Meeting in the Berlin City Palace (Wilhelm II, Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, War Minister Falkenhayn, Chief of Staff Moltke, Chief of the Military Cabinet Lyncker, Grand Admiral Tirpitz, later joining: Chief of the Navy Cabinet Müller, State Secretary for Foreign Affairs Jagow). Wilhelm II signs general mobilization, the first day of mobilization is August 2nd. After signing, Lichnowsky's (false) report from London gave rise to the hope of British neutrality, British condition: no hostilities against France, London would then also have a moderating effect on France. Wilhelm II, supported by Bethmann Hollweg, is now calling for the western deployment to be stopped and for the army to be sent east, which Moltke describes as impossible: “We cannot do that, if that happens, we will mess up the whole army and leave each other Chance of success. In addition, our patrols have already entered Luxembourg and the division in Trier will follow soon after. " Although Moltke is furious, the emperor revokes the order to enter Luxembourg.

- Berlin 12:52 p.m .: Text of the declaration of war is sent to Ambassador Pourtalès in St. Petersburg with the stipulation that it be handed over at 5 p.m. CET.

- St. Petersburg 7 p.m. local time: Ambassador Pourtalès hands over German declaration of war.