Mission Hoyos

As Mission Hoyos , or Hoyos mission is called the journey of the Austro-Hungarian special envoy Legationsrat Alexander Graf von Hoyos to Berlin on 5 and 6 July 1914 the beginning of the July crisis . The aim of his mission was to get the support of the German Reich for a military intervention by Austria-Hungary against Serbia . The significance of the process lies in the fact that Hoyos succeeded in this: he received the so-called " blank check ", which led to the war with Serbia and, as a result, to the First World War .

Reactions after the Sarajevo attack

Conversations of an informal nature

On the day after the fatal assassination attempt on Archduke heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie , a meeting took place in the office of the head of cabinet of the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Ministry. Chamberlain and Privy Councilor Franz von Walterskirchen, Legation Councilor Alexander von Musulin and Undersecretary Johann von Forgách discussed a possible course of action after the death of the heir to the throne. Head of cabinet Hoyos himself was unable to attend. Musulin saw the attack as an opportunity to take action against Serbia and to be able to "carry along the Slavic parts of the monarchy [...] for the war against Serbia". The meeting ended with Forgách agreeing to the idea of a war with the words: "If you can win the Minister [Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold ] over to the plan, I have nothing against it."

Cabinet chief Hoyos had already had a secret conversation with the German publicist Victor Naumann on July 1 , about which he noted in his notes:

“He himself [Naumann] was able to perceive that not only in army and naval circles but also in the Foreign Office are no longer as completely hostile to the idea of a preventive war against Russia as they were a year ago. In his opinion, after the bloody deed in Sarajevo, it was a question of existence for the monarchy not to leave this crime unpunished, but to destroy Serbia. […] Austria-Hungary would be lost as a monarchy and great power if it did not use this moment. I replied to Dr. Naumann, that I, for my part, consider a solution to the Serbian question to be absolutely necessary and that it would be of great value to us in any case to be certain that we could possibly count on Germany's backing. "

Before the meeting of the Council of Ministers taking place the next day , Musulin informed Cabinet Chief Hoyos about the conversation that had taken place the previous day. In a meeting that followed, Foreign Minister Berchtold also approved Musulin and Forgách's war plans. Hoyos, who initially opposed, immediately went to the office of the Hungarian Prime Minister István Tisza to report that “the minister wanted to make the war again”. Tisza spoke out directly against a possible war against Serbia. In the event of a victory that would have been expected in the event of a swift strike against Serbia, at least parts of Serbia would have been added to the Hungarian half of the Danube Monarchy. This would have strengthened the Slav population to the detriment of the Magyars .

Council of Ministers meetings

Tisza remained the only opponent of a war against Serbia during the Council of Ministers' meetings of the following days. Foreign Minister Berchtold's position was clearly in favor of a blow against Serbia, the Austrian Prime Minister Karl Graf von Stürgkh planned to put down the Slavic national movements in the monarchy with an action against Serbia and was already thinking “of the war as an enterprise also of a domestic political nature”. The chief of the general staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf , saw the "moment to resolve the Serbian question" had come.

In order to avoid the risk associated with a war, Tisza telegraphed Emperor Franz-Joseph on July 1st :

"Only after my audience did I have the opportunity to speak to Count Berchtold and learn of his intention to make the atrocity of Sarajevo on the occasion of the reckoning."

Although the majority of the ministerial conference advocated intervention in Serbia, they were aware of the fact that an approach without coordination and backing with the German Reich would not be feasible. A simultaneous intervention by Russia would have resulted in a stalemate, and intervention by France and Great Britain was also to be feared. In any case, the supporters of an intervention could not simply bypass Tisza's resistance. As Prime Minister of Hungary he represented one half of the Danube Monarchy and had a kind of veto right in common matters.

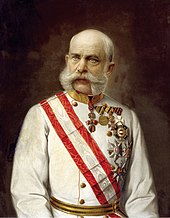

For this reason, the Council of Ministers meeting, a finished in the days before the murders of Sarajevo memorandum, the Austria-Hungarian security situation in question recorded on the Balkan Peninsula in dark colors decided to provide them with a postscript and together with a handwritten letter of Emperor Franz Joseph after To send Berlin to get the support of the German Emperor Wilhelm II . The memorandum was a document from the head of the section in the kuk Foreign Ministry, Franz von Matscheko , which he had probably submitted to the ministry on June 24th and which dealt with the situation in the Balkans after the end of the Balkan wars. The Balkan League , founded in 1912 at the instigation of Russia and directed against the Ottoman Empire , from which Bulgaria had withdrawn after the First Balkan War, and Romania , courted by the Triple Entente , were presented as a threat that was now becoming a threat to the dual monarchy. It is necessary to maintain the now good relationship with Bulgaria and to satisfy Romania and Serbia through concessions. The postscript stated that it had not been possible to reach an agreement with Serbia and that it was time "with a determined hand to tear the threads that their [the dual monarchy] opponents want to condense into a network over their heads."

Franz-Josef's personal letter, which was drawn up by Hoyos himself, added to the memorandum that “Austria and Serbia can no longer coexist” and armed conflict is now inevitable.

The significance of the decisions made these days becomes clear in an interview from 1917, when the political journalist Heinrich Kanner approached then Finance Minister Leon Biliński about the July crisis.

“Bilinski said… we decided it (the war) earlier, that was right at the beginning. I [Kanner] asked when. ... It fluctuated between July 1st and 3rd, but then seemed to be drawing towards July 3rd. The consequences of such a war were also clear to everyone involved ... no, they already knew that it could be a great war, the Kaiser especially expected it. [... Franz Joseph said] Russia cannot possibly accept that. "

In addition, Foreign Minister Berchtold Alexander Hoyos verbally instructed "to tell Count Szögény [the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Berlin] that we consider the moment to have come [...] to settle accounts with Serbia".

Mission in Berlin

Preliminary talks

Hoyos was the “ideal partner” for the talks in Berlin because he had already brought home German support during the Bosnian annexation crisis. He wanted to repeat this success and suggested a new mission to Berchtold. On the morning of July 5, Hoyos reached Berlin by night train. Since Emperor Wilhelm intended to go on his trip to the north on the morning of the next day, Ambassador Szögyény had already arranged an audience for the afternoon of the same day. Hoyos immediately went to see the ambassador to prepare the audience. The memorandum also contained a handwritten postscript by Berchtold that it was now “all the more imperious” of Austria-Hungary “to tear with a determined hand the threads that their opponents want to condense into a net over their heads.” The letter Franz -Joseph went so far as to see Serbia as a “hearth of criminal agitation”. In the letter from the Kaiser to Kaiser Wilhelm, dated July 2nd, it said: “In the future, my government's efforts must be directed towards the isolation and downsizing of Serbia.” Serbia, the “pivot of Pan-Slav policy”, should “be a political power factor on the Balkans switched off ”.

After Hoyos had given the Ambassador Szögyény comprehensive information, they both called in the Undersecretary of State in the German Foreign Office, Arthur Zimmermann . At that time, Zimmermann was in charge of the office, as State Secretary Gottlieb von Jagow was on vacation like most of the other heads of the German Reich. Hoyos also informed Zimmermann, but withheld from him the resistance of the Hungarian Prime Minister Tisza. Instead, Hoyos described that Austria-Hungary wanted to attack Serbia immediately and to carry out a surprise retaliatory strike without any negotiations.

Zimmermann agreed with the ideas put forward; he saw a quick blow from Austria-Hungary as imperative. In this way, a fait accompli could be created that on the one hand consolidates the position of the Danube monarchy in the Balkans and on the other hand precludes a reaction from the Entente powers Russia and France. If there were to be intervention, said Zimmermann, because of the military strength of the German Reich there would be no problem at all in keeping both powers in check. However, UK intervention is by no means expected. After the meeting, Zimmermann informed the German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg .

After the conversation had ended, Hoyos said goodbye to Zimmermann with the following words:

"You couldn't believe that Austria-Hungary would calmly accept the assassination of the heir to the throne in Sarajevo and not react to it."

Audience with Kaiser Wilhelm

The audience of Szögyény and Hoyos began around 1 p.m. It was astonishing that the Hohenzoller received the two alone. There were no advisers whatsoever and no preparations whatsoever for the audience, although this was customary and would have been appropriate in such a foreign policy situation. Neither Bethmann-Hollweg nor Zimmermann took any steps to attend the audience.

It can therefore be assumed that Wilhelm did not initially perceive Emperor Franz-Joseph's concern as a serious threat to Austria-Hungary. After studying the sources submitted by Hoyos and Szögyény, he refused German support for a war: Wilhelm assured us that “he expected serious action on our part against Serbia, but he had to admit that he was keeping an eye on a serious European complication had to and did not want to give a definitive answer before consulting the Chancellor ”.

But Szögyény continued to try to get the emperor to accept, and after lunch in large company the audience continued. The ambassador once again emphatically described to the emperor how serious the situation was and described an existential threat to the monarchy and the dangers associated with it.

Here, Wilhelm must have rethought. Obviously, Szögyény's description of an existential threat was convincing enough that Wilhelm let his personal relationship with Emperor Franz-Joseph and his ideas of honor and chivalry become the basis of his further course of action. Szögyény as well as Hoyos had set the right levers in motion here to get Wilhelm to give in at least partially. With his commitment to loyalty to the alliance, Wilhelm did not refer to the current situation, but repeated his declaration from the days of the Bosnian annexation crisis. In general, people, words and goals were strikingly similar to those in the annexation crisis in 1908.

In 1908, Szögyény, accompanied by Hoyos, traveled to Rominten , a hunting lodge of Kaiser Wilhelm, to seek support from the German Empire during the crisis. Hoyos wrote about this in his report to Vienna:

“At the end of the conversation I mentioned the threatening situation in Serbia. To which His Majesty replied that the Serbs should keep quiet so as not to run the risk of being overthrown by Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. [...] From the gracious statements made by His Majesty, it was clear [...] how firmly the same is determined to support the same [Austria-Hungary policy] in unchanging loyalty to the alliance. "

In addition, the rather profane result of Szögyény and Hoyos' audience was reported to Vienna with far greater implications. The ambassador claimed that Wilhelm advised not to wait any longer before proceeding against Serbia, as the opportunity had now come. Of course, "Russia's attitude [...] would in any case be hostile, but he [Wilhelm] had been prepared for years, and should there even come to a war between Austria-Hungary and Russia, then we could be convinced that Germany was in the usual loyalty to the alliance." will stand by our side ”.

The conversation between Wilhelm and War Minister Erich von Falkenhayn immediately after the audience ended shows that Szögyény had at least exaggerated with his report . Wilhelm expressed his opinion “that the Austrian government is serious about their language, which was decided against earlier”. Nevertheless, too many things have to be clarified before a possible war, so that “in no case will the next few weeks bring a decision”. When Falkenhayn asked him whether it was necessary to mobilize the German army or at least to keep it ready, Wilhelm replied with a simple "No".

In the evening, Wilhelm had a conversation with Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and Zimmermann about the audience. Wilhelm explicitly emphasized that it was the task of German foreign policy "to work with all means [...] to prevent the Austro-Serbian dispute from developing into an international conflict." Nevertheless, Germany's vital interest requires the intact preservation of Austria. But as early as July 8th, the fickle Wilhelm urged the German ambassador in Vienna Heinrich von Tschirschky to take action against Serbia: He should “declare with all emphasis that an action against Serbia is expected in Berlin and that Germany does not understand it if we let the given opportunity pass without struck ”. Berlin was not an “innocent victim” of a “Viennese intrigue”, but rather actively, encouragingly and even somewhat impatiently urged its ally to act.

Reactions in Vienna

Hoyos returned to Vienna on July 6th and reported the results of his mission to Berchtold, Stürgkh and Tisza the following day .

In an interview with Undersecretary Zimmermann and Bethmann Hollweg, Hoyos mentioned the “complete partition” of Serbia as a post-war goal (a bizarre improvisation). Tisza was furious when he learned that during the audience, without any instructions, Hoyos had given statements about the division of Serbia after a successful war as the official opinion of the Danube monarchy. Hoyos had literally said that Serbia had to "disappear". After Tisza's protest, Berchtold presented these statements as the Count's personal opinion. In " his eagerness to pave the way for a war of conquest ", Hoyos thereby endangered the success of his mission.

Tisza still disagreed with the general readiness for war. Although he also saw “the possibility of an action against Serbia approaching”, he never wanted “a surprise attack on Serbia without prior diplomatic action, as this seemed to be intended and, unfortunately, was also discussed in Berlin [...] agree".

After a long debate, the Council of Ministers decided, with the supposed support of the German Reich in the back, to bring about a "quick decision on the dispute with Serbia". Tisza's concerns were met. An ultimatum should make concrete demands on Serbia, which would then lead to a mobilization of the Austro-Hungarian troops after a rejection . With the exception of Tisza, all those present agreed “that a purely diplomatic success, even if it ended in a blatant humiliation of Serbia, would be worthless and that such far-reaching demands would have to be made on Serbia, which indicated a rejection, and thus a radical one Solution would be initiated by military intervention ”.

A war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was de facto already decided at the beginning of July, although it was weeks before the war broke out.

The scope of Hoyos' actions can be seen in his own words, which one of his employees at Ballhausplatz , Consul Emanuel Urbas, reported:

“ As a deeply moral character, he suffered so terribly from the historical responsibility that weighed on him after the collapse of Austria-Hungary, as I know, that in the winter of 1918/19, which he spent in retirement in Friedrichsruh, he went with them for months wrestled with the thought of suicide. "

Reception in history

If the Fischer controversy caused big waves in the 1960s and changed the perception of the question of war guilt in the Federal Republic permanently, this reception of the First World War also related almost exclusively to the German Empire. According to Fischer, a predominantly "war guilt" of the German Reich was taken as given, while the other great powers of the time were held to be "guilty" with a far smaller proportion.

The question of the type and extent of the German war guilt remains open to this day and is extremely controversial, as evidenced by the literature on the so-called July crisis and the success of Christopher Clark's current book , which continues to appear in large numbers .

In Austria, however, the discussion about Fischer's theses did not lead to a rethinking of the assessment of the importance of Austria-Hungary for the outbreak of war in 1914. Only Fritz Fellner and Rudolf Neck took the new view into account, but were largely ignored by the public. This ignorance of a fact-mounted reassessment of the role of Ballhausplatz in the July crisis Fellner explained by the situation in Austria after 1945. The "awakening from the pan-German dream" had led to the need to Habsburg monarchy reinterpret positive and a new founding myth of the Second Republic to make, the "conservative present of Austria was linked with the help of an old Austrian historical image [...] to an allegedly conservative past in the Habsburg Empire aimed at maintaining peace and the status quo" .

The number of works that specifically dealt with Hoyos' mission remained correspondingly low in both Germany and Austria. The first monograph on the topic is The Hoyos Mission. How Austro-Hungarian Diplomats started World War I (2011) by Eric A. Leuer. He puts forward the thesis that the protagonists in the Austro-Hungarian diplomatic corps deliberately pushed the war with the knowledge and consent of Berchtold and Emperor Franz-Josef. The aim was to regain hegemony over the Balkans through a military crackdown on Serbia. Vienna had assumed the wrong premise that Germany was extremely strong militarily. In the eyes of Vienna it was even considered invincible and thus a war together with the ally in the dual alliance was seen as safe to win even with the participation of the Entente . In his review in the online journal sehepunkte, the historian Salvador Oberhaus rejects Leuer's theses and methodology and accuses him, among other things, of selective considerations, such as limiting himself to the assassination attempt in Sarajevo instead of analyzing its causes or ignoring the "escalation policy of Berlin in the July crisis" . The “rigid dichotomy of guilt and innocence” is reminiscent of “the historical revisionist debates of the 1960s and 1980s” .

literature

- Rudolf Agstner : From emperors, consuls and merchants. Vol. 2. The k. (u.) k. Consulates in Arabia, Latin America, Latvia, London and Serbia , Vienna 2012.

- Luigi Albertini : The Origins of the War of 1914. 3 volumes, Oxford 1953.

- Holger Afflerbach : The Triple Alliance. European great power and alliance politics before the First World War. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-205-99399-3 .

- August Bach: German legation reports on the outbreak of war in 1914. Berlin 1937.

- Volker Berghahn : The First World War. Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-48012-8 .

- Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vienna / Leipzig 1930.

- Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf : From my service 1906–1918. Volume 4: June 24, 1914 to September 30, 1914. The political and military events from the murder of the prince in Sarajevo to the conclusion of the first and the beginning of the second offensive against Serbia and Russia. Rikola-Verlag, Vienna / Leipzig / Munich 1922.

- Fritz Fellner : The "Mission Hoyos". In: Fritz Fellner, Heidrun Maschl, Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig (eds.): From the Triple Alliance to the League of Nations. Studies on the history of international relations 1882–1919. Publishing house for history and politics, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-7028-0333-5 . review

- David Fromkin : Europe's last summer. The seemingly peaceful weeks before the First World War. Blessing, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89667-183-9 .

- Hugo Hantsch : Leopold Graf Berchtold, Grand Seigneur and statesman. 2 volumes, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1963.

- Alexander von Hoyos : My mission to Berlin. In: Fritz Fellner, Heidrun Maschl, Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig (eds.): From the Triple Alliance to the League of Nations. Studies on the history of international relations 1882–1919. Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-7028-0333-5 , pp. 135–141.

- Karl Kautsky , Max Montgelas (ed.): The German documents on the outbreak of war in 1914. Volume 1, Berlin 1921.

- Friedrich Kießling : Against the great war? Relaxation in international relations 1911–1914. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56635-0 .

- Miklós Komjáthy (Ed.): Protocols of the Joint Council of Ministers of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (1914–1918). Budapest 1966.

- Eric A. Leuer: The Hoyos Mission. How Austro-Hungarian diplomats started the First World War. Centaurus, Freiburg i. B. 2011, ISBN 978-3-86226-048-5 .

- Wolfgang J. Mommsen : The Great Disaster in Germany. The First World War 1914–1918. Handbook of German History 17, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-608-60017-5 .

- Wolfgang Schieder (Ed.): First World War. Causes, origins and aims of the war. Cologne / Berlin 1969.

- Harry F. Young: Prince Lichnowsky and The Great War. University of Georgia Press, Athens (Georgia, USA) 1977, ISBN 0-8203-0385-2 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Alexander von Hoyos: My mission to Berlin . After: Fritz Fellner : The "Mission Hoyos" . In: Fritz Fellner, Heidrun Maschl (Ed.): From the Triple Alliance to the League of Nations. Studies on the history of international relations 1882–1919 . Verlag für Geschichte und Politik, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-7028-0333-5 , pp. 135 ff.

-

↑ Ludwig Bittner , Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs . Vienna / Leipzig 1930, Volume 6: p. 335 f.

Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents. Hanover 1963, Volume 1: p. 62. - ↑ Miklós Komjáthy (ed.): Protocols of the Joint Council of Ministers of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (1914–1918) , Budapest 1966, p. 84 f.

- ^ Leo Valiani: Negotiations between Italy and Austria-Hungary 1914–1915. In: Wolfgang Schieder (Ed.): First World War. Causes, origins and aims of the war. Köln, Berlin 1969, pp. 317–346, here: p. 337.

- ^ Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf: From my service 1906–1918 , Vienna, Leipzig, Munich 1922, Volume 4, p. 22 f.

- ↑ Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vienna, Leipzig 1930, Volume 8, p. 248 (No. 9978).

- ↑ a b c Christopher Clark : The Sleepwalkers. How Europe went to War in 1914. Allen Lane, London et al. 2012, ISBN 978-0-7139-9942-6 (from the English by Norbert Juraschitz: Die Schlafwandler. How Europe moved into the First World War. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-421-04359-7 ; as audio book: Random House Audio, 2013, ISBN 978-3-8371-2329-6 ).

- ↑ Miklós Komjáthy (ed.): Protocols of the Joint Council of Ministers of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy (1914–1918) , Budapest 1966, p. 82 ff.

- ↑ H. Bertil A. Petersson: The Austro-Hungarian Memorandum to Germany of July 5, 1914. In: Scandia , Vol. 30, No. 1 (1964), pp. 138-190.

- ↑ Robert A. Kann : Emperor Franz Joseph and the outbreak of the world war. Vienna 1971, p. 16.

- ^ Hugo Hantsch: Leopold Graf Berchtold. Grand master and statesman. Graz, Vienna, Cologne 1963, Volume 2, p. 573.

- ↑ Manfried Rauchsteiner: The death of the double-headed eagle. Austria-Hungary and the First World War . Böhlau Verlag, Vienna / Graz / Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-222-12454-X , p. 70.

- ^ Friedrich Thimme: Front against Bülow. Statesmen, diplomats and researchers on his memorabilia. Munich 1931, p. 232.

- ↑ Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914. How Germany stumbled into the First World War. Böhlau, Cologne, Vienna 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hanover 1963, Volume 1: p. 63 f. (No. 9); and Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs . Vienna / Leipzig 1930, Volume 8, pp. 250 ff. (No. 9984).

- ^ Hans Hallmann: Foreword in: Fritz Kern: Sketches for the outbreak of war in 1914 , Darmstadt 1968, p. 11; and Imanuel Geiss: July crisis and outbreak of war 1914 , Hanover 1964, no. 39.

- ^ Luigi Albertini: The Origins of the War of 1914 , Volume 2, Oxford 1953, p. 144.

- ^ Kurt Jagow : The Potsdam Privy Council. In: Süddeutsche Monatshefte , Munich 1928, p. 780.

- ↑ Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914 , p. 26.

- ^ Kurt Jagow: Der Potsdamer Kronrat , in: Süddeutsche Monatshefte , Munich 1928, p. 782.

- ↑ This assumption corresponds to: August Bach: German legation reports on the outbreak of war in 1914. Berlin 1937, p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Fritz Fellner: The "Mission Hoyos" . In: Fritz Fellner, Heidrun Maschl (Ed.): From the Triple Alliance to the League of Nations. Studies on the history of international relations 1882–1919 . Verlag für Geschichte u. Politics, Vienna 1994, ISBN 3-7028-0333-5 , pp. 112–141, here: p. 116.

- ↑ Ludwig Bittner, Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Volume 1, No. 294, p. 226.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss: July crisis and outbreak of war. No. 21.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss: July Crisis , No. 26.

-

↑ Jörn Leonhard : Pandora's box. The history of the First World War. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66191-4 , p. 91.

Imanuel Geiss (Ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hanover 1963, Volume 1: p. 85. -

↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hannover 1963, Volume 1: p. 128 (No. 50).

Ludwig Bittner , Hans Uebersberger (ed.): Austria-Hungary's foreign policy from the Bosnian crisis in 1908 to the outbreak of war in 1914. Diplomatic files from the Austro-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Vienna / Leipzig 1930, Volume 8: p. 370f. (No. 10145). - ↑ Annika Mombauer : The July crisis. Europe's way into the First World War. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66108-2 , p. 53.

- ↑ Imanuel Geiss (ed.): July crisis and outbreak of war. A collection of documents . Hannover 1963, Volume 1, No. 115; and József Galántai: Hungary in the First World War . Budapest 1989, ISBN 963-05-4878-X , p. 34.

- ↑ Günther Kronenbitter: "War in Peace". The leadership of the Austro-Hungarian army and the great power politics of Austria-Hungary 1906–1914 . Verlag Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56700-4 , p. 468.

- ↑ Bittner, Uebersberger: Austria-Hungary's Foreign Policy , Volume VIII, p. 344.

- ^ Bittner, Uebersberger: Austria-Hungary's Foreign Policy , Volume 8, p. 344.

- ↑ Ernst U. Cormons: Fates and Shadows. An Austrian autobiography. Salzburg 1951, p. 163.

- ↑ See: John CG Roehl: Wilhelm II . Munich 1993-2008; Fritz Fischer: Reach for world power. The War Target Policy of Imperial Germany 1914/1918. Düsseldorf 1964; The outbreak of war "His guilt is very great". The Wilhelm II. biographer John Röhl on the responsibility of the emperor for the outbreak of the First World War . Spiegel special 1/2004.

- ↑ See example: Friedrich Kießling: Against the Great War? Relaxation in international relations 1911–1914. Munich 2002; Volker Berghan: The First World War , Munich 2003; James Joll, Gordon Martell: The Origins of the First World War. Harlow, et al. a. 2007; Wolfgang Mommsen, The Great Catastrophe in Germany. The First World War 1914–1918. Handbook of German History, Volume 17, Stuttgart 2002; Lüder Meyer-Arndt: The July Crisis 1914. How Germany stumbled into the First World War. Cologne, Vienna 2006.

- ^ Fritz Fellner: On the controversy over Fritz Fischer's book "Griff nach der Weltmacht". In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung, Volume 72, Vienna 1964, pp. 507-514; as well as: Rudolf Neck: War target policy in the First World War. On the controversy over the work of Fritz Fischer, "Reach for World Power". In: Mitteilungen des Österreichisches Staatsarchives, Volume 15, Vienna 1962, pp. 565–576.

- ↑ Fritz Fellner: The "Mission Hoyos". In: Fritz Fellner, Heidrun Maschl, Brigitte Mazohl-Wallnig (eds.): From the Triple Alliance to the League of Nations. Studies on the history of international relations 1882–1919. Vienna, Munich 1994, p. 112 f.

- ↑ Eric A. Leuer: The Mission Hoyos. How Austro-Hungarian diplomats started the First World War. Freiburg i. B. 2011, ISBN 978-3-86226-048-5 .

- ^ Salvador Oberhaus: Review of Die Mission Hoyos , in: Sehepunkte 12, No. 10 http://www.sehepunkte.de/2012/10/20325.html .