History of Czechoslovakia

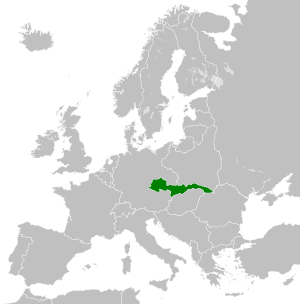

| Territory of Czechoslovakia in the historical course | ||

|

||

The presentation of the history of Czechoslovakia given here covers the period from 1848 to 1992, including the prehistory. Czechoslovakia existed as a state from 1918 to 1939 and again from 1945 to 1992 ( de jure also during the Second World War ).

The concrete history of Czechoslovakia began in the First World War . The Czech and Slovak personalities Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk , Edvard Beneš and Milan Rastislav Štefánik managed in September 1918 to win support from the Allies for the Czechoslovak National Committee , which was preparing its own state. Czechoslovak troops fought alongside the Allies in the final year of the war. In autumn 1918 the new state could be constituted. The National Socialist German Reich annexed him temporarily ( March 1939 ). In 1992, the parliament of Czechoslovakia resolved to dissolve the federation on December 31, 1992 and thus the formation of the two new states, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, from January 1, 1993.

Prehistory (1848–1918)

Revolution year 1848 and the consequences

Petition to Emperor Ferdinand I.

In the troubled political climate of Europe in 1848, the Reappeal Club met on March 11th in Prague , a secret society oriented towards the liberation struggle of the Irish against the British, and elected a 28-member committee ( National Committee ). This met the next day in the old town hall and commissioned lawyer Adolf Maria Pinkas to draft a petition to the emperor . The core of the petition , which was introduced on March 19 by a Bohemian delegation at the Viennese imperial court, consisted of demands on the nationality issue . It was called for the "equality of the Bohemian nationality with the German in all Bohemian countries in schools and offices". In addition, "the Bohemian countries should reunite administratively and agree to the constitution of a joint Bohemian state parliament." The historical constitution of the Wenceslas Crown was implicitly invoked ; The aim was to restore the Bohemian kingdom as it had existed before the defeat on White Mountain . (The Viennese court was aware of the explosiveness of these wishes. Even if not mentioned directly at the time, the wishes largely corresponded to those that the Magyars received in 1867 in the so-called compensation .)

The emperor sent the delegation a letter in which he made concessions to the Bohemians, but otherwise referred to a future constitution for the entire monarchy. The delegation returned to Prague with no concrete results.

National sparks in the Paulskirche and at the Slav Congress

On March 31, 1848, a preliminary parliament met in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt to prepare, among other things, elections for a German National Assembly .

At that time Prussia was the socially and economically emerging power, as it opened up to new ideas, while reactionary forces in the Habsburg Empire hindered progress. In addition, the far east-reaching areas of the Austrian Empire, such as Galicia and Bukovina, were nowhere near as well developed as the western parts of the monarchy, including Bohemia. The linguistic heterogeneity of the state was also particularly pronounced: while German was predominantly spoken in the Alpine crown lands, around 1850 in Bohemia more than sixty, in Moravia around 70 percent and in Austrian Silesia around 20 percent of the inhabitants named Czech as their mother tongue; 6.6 million people lived in the Bohemian countries at that time.

In the first half of the 19th century, the different languages were of little importance in the Danube Monarchy, as society at that time was not organized according to national identities, but according to “class, religion and property”. The nobility , civil servants , clergy , wealthy bourgeoisie and the military ruling class supported the emperor's power. The Habsburg Monarchy emerged from what is now Lower Austria with Vienna as its center. Germans held the leading role in the monarchy. Viewed as a whole, the Habsburg Empire had no national ambitions, but did not want to give up the role of the highest arbitrator in Germany that it had held for centuries.

The national ideas that elicited the German National Assembly also made their way to Bohemia. While the German Bohemians supported the unification of Germany under Austrian leadership, the Czechs had reservations about going under in a German "sea", even if it had a liberal constitution.

Due to the now occurring differences had the idea of Bohemian, of Bernard Bolzano by the merger of Bohemia into a nation no chance. Bohemism was crushed between German and burgeoning Czech nationalism . The emerging Czech nationalism was not based on the goal of a common language and culture, but on the increasingly strong German enemy image . This is characterized by the saying “ Svúj k svému ” (“Everyone to his own ”).

The nationalism of the German Bohemians expressed itself, among other things, in the fact that they did not see the Czechs as being of equal value and consequently not having equal rights. Czech nationalism was expressed, for example, in the establishment of the Národní noviny (national newspaper ). The author Karel Havlíček Borovský was of the opinion that there could be equality between Germans and Czechs in offices and schools, but the Czechs are the "firstborn" and therefore the labels on shops and public buildings must be in Czech, which means that the German inscription must be removed. This article did nothing to ease the situation.

František Palacký wrote the five-volume work History of Bohemia from 1836 to 1867 , which became the basis of Czech historiography and relevant to national consciousness . On this basis Havlíček came to the opinion: "Our entire history is an incessant struggle against the Germans."

Leading figures in the Czech national movement such as Palacký founded patriotic self-help organizations that enabled many of their compatriots to participate in community life even before independence.

A delegation with a petition has now been sent to the Kaiser in Vienna. But since the revolution was ruling in Vienna and the revolutionaries were initially militarily successful, the Austrian government felt compelled to play for time, and in the “Bohemian Charter” of April 1, 1848, guaranteed political equality. Angry Germans then organized themselves in the "Association of Germans from Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia to Maintain Their Nationality ". (Ultimately, this petition did not bring anything concrete to the Bohemians either, since after the suppression of the revolution in autumn 1848 the emperor changed and Franz Joseph I was not bound by earlier promises.)

The St. Wenceslas Bath Committee met again in Prague on April 10, 1848 and was transformed into the Národní výbor (National Committee). The main task of the Národní výbor was to draw up a constitution for the Bohemian lands. The national committee was thus the counterpart to the Paulskirche parliament . The draft constitution should be worked out quickly so that it would be available at the start of the Vienna Reichstag . But initially the overall Bohemian solution failed because the representatives from Austrian Silesia and Moravia declared that they wanted to make their decisions autonomously.

At the Slavic Congress , which met in Prague on June 2 on the initiative of Palacký and Pavel Josef Šafařík , the participants agreed to take an independent Slavic path as an alternative to the Frankfurt National Assembly. The Czech way stood in contrast to the political situation in the Habsburg Empire and the Frankfurt Constitutional Convention, which dreamed of a unitary state. Palacký demanded that the empire be restructured into a "union of peoples with equal rights". The thoughts of the Slavs Congress also reached the streets of Prague, where acts of violence broke out as Prague demonstrators marched through the streets in protest. During the Pentecost uprising there were clashes between Czech workers and students and the Imperial and Royal soldiers stationed in Prague . The demonstrators demanded a tougher pace from the Czechs than Palacký articulated. It was the first time that there were riots against the Germans living in Prague .

Kremsier Reichstag and center Prague

During the October uprising in Vienna in 1848, the parliament was moved to Kremsier , where the majority of the Czech MPs took part in the deliberations. At the Kremsier Reichstag, the delegates agreed on a draft constitution; it provided for the largely autonomous government of the individual peoples, but restricted the rights of the monarch only slightly.

Section 19 of the Kremsier draft constitution read: “All peoples have equal rights.” In the meantime, however, the reactionary Austrian government forces had regained the upper hand over the rebellious revolutionaries: the Whitsun uprising in Prague was suppressed, the October uprising in Vienna and the Hungarian struggle for freedom were drawing to a close to. The imperial government therefore no longer saw any reason to accommodate the parliamentarians. On March 7, 1849, she had the Reichstag dissolved by the military.

Meanwhile, on December 2, 1848, Ferdinand I , the last Habsburg to be crowned King of Bohemia, renounced the throne in favor of his eighteen-year-old nephew Franz Joseph . Franz Joseph, who was advised by Prime Minister Felix Fürst Schwarzenberg in a conservative-reactionary sense, did not see himself bound by his uncle's promises. In the March constitution of 1849 that he had imposed , the centralized system was still enshrined and the nationality problem was not taken into account. The Frankfurt National Assembly had also been unsuccessful. The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV had not accepted the imperial crown offered to him by the Paulskirche parliament because he did not want to be dependent on a parliament.

After 1848 Prague became the center of the Czechs, although two thirds of the residents living there declared themselves German. Mostly Germans lived in the center of the city, the Czechs on the outskirts.

Old Austria: compensation with Hungary

After the lost battle of June 24, 1859 at Solferino against the allies France and Italy (Italy was striving for national unification ), the foreign policy situation was bad for the Danube monarchy . As a result, Franz Joseph I opened up to domestic political reforms in order to guarantee the internal stability of the empire.

After the Battle of Königgrätz on July 3, 1866, Prussia took over hegemony in Germany. "With iron and blood" Prussia had brought about the small German solution in the German War . The Czechs, however, remained loyal to the Danube Monarchy. Palacký and František Ladislav Rieger offered an "unbreakable loyalty of the Czechs to the House of Habsburg ". In return, they demanded “a federalization of the monarchy.” In the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the Austrian Empire , founded in 1804, was divided into two states under constitutional law: Cisleithanien and Transleithanien - or Austria and Hungary. Together they formed the Austro-Hungarian monarchy of Austria-Hungary , the head of state, army and foreign, and possessed of Finance in common, but all other government functions separately.

Czechs are disadvantaged compared to Magyars

The Czechs felt cheated of their compensation. They said they should have the same rights as Hungarians . However, the governments in Vienna and Budapest did not respond to the Czech demands, probably because otherwise the southern Slavs living in both halves of the empire would have made similar claims and the leading politicians could not imagine dividing the monarchy into four states. Franz Joseph did not have himself crowned King of Bohemia for fear that the Czechs might interpret this as recognition under constitutional law. Wounded in their pride by these circumstances, the Czechs turned more and more to nationalism. In 1867, the leading politicians Palacký and Rieger did not travel to the Imperial Council convened in Vienna , but went to an "ethnographic exhibition" in Moscow, at which Russian scholars propagated Pan-Slavism . They now said that Pan-Slavism would bring the solution to the Czech dilemma.

Czech majority in the Parliament of Bohemia

The Austrian Prime Minister Eduard Taaffe issued language ordinances on April 19, 1880. These said that Czech became the official language in addition to German in those territories where the majority of the population was German. Furthermore, Taaffe persuaded the Reichsrat to expand the right to vote. The minimum tax payment (“census”) that men had to prove in order to have the right to vote was reduced from ten to five guilders . This gave the Czechs a majority in the Bohemian state parliament , with which the Czechs had achieved supremacy in the Bohemian countries, although the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was dominated by German-Hungarian as a whole.

Young Czechs, Badeni riots and Moravian compensation

From the 1880s on, a new generation grew up on the Czech and German sides, which increasingly relied on confrontation. The Young Czechs (Mladočeši), a party founded on December 27, 1874, achieved a majority in the state elections in 1889 and 1891. Their voters wanted the country to be as independent as possible and no longer strived for a German-Czech balance, as the conservative old Czechs were looking for.

In order to win the Young Czechs to support the government, the Imperial and Royal Prime Minister Count Badeni issued language ordinances for Bohemia and Moravia on April 5, 1897. These ordinances provided that all civil servants who entered the public service in these countries from July 1, 1901 should demonstrate knowledge of both German and the Czech language. However, since far more Czechs spoke German than, conversely, Germans mastered the Czech language, numerous German MPs in the Reichsrat - especially from the ranks of the German national and liberal parties - protested against the draft law and tried to prevent the implementation of the language ordinance with the help of a parliamentary obstruction . At the same time, a large number of demonstrations took place in Bohemia and Moravia, demanding the immediate withdrawal of the language regulations and the resignation of the Badeni government. After mass protests broke out in Vienna and Graz on November 26 and 27, 1897, the emperor dismissed the head of government. In 1899 the language ordinances were finally repealed, which in turn gave rise to protests and obstruction in the Reichsrat on the part of the Czech Republic.

In 1905, the Moravian Landtag passed four state laws that became known as the Moravian Compensation . In Moravia they were supposed to ensure a solution to the nationality problems between Germans and Czechs and thus bring about an Austrian-Czech balance . At the same time, efforts to achieve a Bohemian settlement, which had failed at the end of the 19th century, were resumed in 1906 under Prime Minister Freiherr von Beck. However, they did not lead to any result until the beginning of the First World War. Meanwhile, the confrontation course of the ethnic groups at the state level led to the fact that the cisleithan Reichsrat was again unable to work from 1907.

Economic boom

In the 1890s there was an economic boom in Austria-Hungary . The economic center of the Danube Monarchy were the Bohemian countries. Many Czechs now experienced an improvement in their standard of living. This enabled the Czechs to further emancipate themselves from the Germans of the monarchy, who in the long term saw their de facto privileges in the state in danger from the Slavic majority in Austro-Hungarian Austria.

First World War: Czechoslovak state prepared

The Czechs viewed the close cooperation between Vienna and Berlin with concern. After a victory of the Central Powers, they feared the unification of Austria with Germany, which would spread German dominance again and the Czechs would lose their national identity again.

The Czech scholar and politician Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk went into exile in 1914 and tried to build up a network from outside in order to achieve the constitution of an autonomous Czecho-Slovak state. He envisioned an independent state orientated towards the West and taking its place in the reorganized Europe. For Masaryk, the war offered the possibility of building a progressive and democratic Europe with an independent Czechoslovakia.

The Foreign Minister of Great Britain, Edward Gray , received a draft ( Independent Bohemia ) from Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in April 1915 , which provided for the merger of the Czech Republic with Slovakia. On the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the burning of Jan Hus on July 6, 1915, the Czechs living abroad commemorated him in the Reformation Hall in Geneva. Masaryk "chose this day in order to build on the historical continuity, also in front of the eyes of the world, to the history of our state." On November 14th, 1915 Masaryk announced the establishment of a "foreign action committee for the establishment of an independent Czecho-Slovak state" in Paris. known.

Masaryk then moved from Paris to England. In the book Das neue Europa he wrote an essay in which he described the war aims of the Germans . He wrote that the Germans wanted a “Pan-Germanic Central Europe”. These and other activities caused Western intellectuals to be interested in the ethnic mix in Central Eastern Europe.

The National Council of the Czech Lands was established on February 5, 1916 with the permission of the French government. The Slovaks in exile constituted the National Council of the Czech Lands in cooperation with the Czechs abroad. This marked the path to a government in exile. Masaryk arrived in Russia in 1917. There was a union formed from Czech and Slovak emigrants, prisoners of war and defectors - the Czechoslovak Legions . She fought on the Russian side at the front and supported the White Army against the Bolsheviks after the outbreak of the civil war . The establishment of its own army and the participation in the war on the side of the Entente formed the basis for the participation of Czechoslovak representatives in the peace treaty negotiations of St. Germain and Versailles in 1919.

Masaryk had made important allies not only in Europe, but also in the United States. "We got along pretty well - well, we were both professors." This is how Masaryk described his relationship with US President Woodrow Wilson . Masaryk succeeded in allaying American fears of a "Balkanization" of Europe. The later famous Fourteen Points by Wilson contained the goal that the Danube states develop freely and independently, but the necessary destruction of the Habsburg monarchy was not explicitly mentioned.

While Masaryk drove the company forward in the USA, Edvard Beneš negotiated with France and Great Britain . He wanted the two governments to recognize the National Council of the Czech Lands as a provisional government, which he achieved on June 3, 1918 in London and on June 29, 1918 in Paris. News came from the USA on August 11th that the Conseil National des pays tchèques could take part in the negotiations of the Allies. On September 3, 1918, the Czechs were recognized by the USA as a participating power and their National Council as the legal representative.

Founding of the state

Emperor Karl's attempt with his Imperial Manifesto of October 16, 1918 to save at least the Austrian half of the empire and convert it into a federal state with extensive autonomy for the individual nations came too late. His invitation to the nationalities of Cisleithania to form national councils was accepted, unless this had already been done without an invitation, as was the case with the Czechs. The nationalities of the monarchy no longer wanted to hear about a federal system under the leadership of the emperor.

The Czechs were not deterred from founding their own, independent and democratically oriented state. Three days after the imperial manifesto, Wilson supported this by demanding that Austria-Hungary recognize the autonomy of the nationalities of the dual monarchy. On October 28, 1918, the Czechoslovak state was proclaimed by representatives of four Czech parties in the Prague parish hall . The Imperial and Royal Governor and the Imperial and Royal Garrison took note of this without contradiction; the governor left the official business to his Czech deputy. Two days later, the new neighboring state of German Austria was constituted . Masaryk, who did not return to Prague from exile until December 21, was elected President of the Republic by the parliamentarians on November 14, and Beneš was elected Foreign Minister of the provisional Czechoslovak government under Masaryk's chairmanship. On the same day, the Karel Kramář government was formed as the country's first regular government.

A group of Slovak politicians proclaimed on October 30, 1918 in Turčiansky Svätý Martin (today Martin ) in the so-called Martin Declaration the annexation of Slovakia to the new state. The Slovak population was largely waiting towards the newly established state.

In 1921 the new state consisted of 14 million people, of whom 50.82% were Czechs and 23.36% German. 14.71% were Slovaks, 5.57% Hungarians and 3.45% Ruthenians . In addition, some Romanians, Poles and Croats lived in the area. The new Czechoslovakia thus presented itself as a state with ethnic diversity in contrast to the Czech national rhetoric like old Austria.

Border regulations with neighboring countries

Hungary

On May 30, 1918, Masaryk had agreed on the integration of Slovakia , which had previously belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary, as well as the Carpathian Ukraine , with the Carpathian -Ruthenians living there and representatives of the Slovaks living abroad. Hungary opposed violent resistance to the establishment of Czechoslovakia because it viewed Slovakia as an integral part of its national territory.

The first Czech attempt to occupy Slovakia militarily failed in December 1918, the second attempt in May / June 1919 turned into a debacle after initial successes. Only a French ultimatum obtained by Beneš, a war threat to Hungary, saved the situation for Prague. The Hungarians finally withdrew. Since July 24, 1919, Slovakia and Carpathian Ukraine definitely belonged to the new common state with the countries of the Bohemian Crown.

German Austria

The provisional national assembly for German Austria , in which all German representatives elected in 1911 to the Imperial and Royal Reichsrat took part, claimed the entire contiguous German settlement area of Old Austria, including parts of the countries of the Bohemian Crown ( Sudetenland ) , for their new state . However, they had not taken any military precautions to take possession of disputed areas.

The German Bohemians and German Moravians , for whom the term “ Sudeten Germans ” increasingly prevailed, offered only a few resistance to their integration into Czechoslovakia at the end of November and beginning of December 1918. There was armed resistance in around eight places, for example on November 27th in the industrial city of Brüx and on December 2nd near Kaplitz. When the newly elected German-Austrian National Assembly met on March 4, 1919 without Sudeten German participation , Sudeten Germans demonstrated in vain for their right to self-determination. The Czech military partially crushed the rallies with armed force. 54 dead and almost 200 injured were mourned. The Treaty of Saint-Germain confirmed the Czechoslovak position in autumn 1919.

Poland

In 1919 the Polish-Czechoslovak border war broke out around the Olsa area . The dispute over a relatively very small area could not be finally settled until 1958. Even smaller territorial claims by Poland on the northern border of today's Slovakia repeatedly led to tensions (see Czechoslovak-Polish border conflicts ).

Peace treaties 1919/20

As a result of the Paris suburb agreements with the loser states of the First World War, the young republic made further minor territorial changes:

- After the Peace Treaty of Versailles, Germany had to cede the Hultschiner Ländchen ( Hlučínsko in Czech ) (January 10, 1920).

- In the Treaty of Saint-Germain, Austria had to cede two small areas of Lower Austria to Czechoslovakia (July 31, 1920), both for strategic reasons:

- the area around Feldsberg (Czech Valticko ) with the places Feldsberg / Valtice , Bischofswarth / Hlohovec , Garschönthal / Úvaly , Unterthemenau / Poštorná and Oberthemenau /

- the area north of Weitra in the Waldviertel (Czech Vitorazská ) with the villages under Wieland / České Velenice , rotting Schachen / Rapšach , Witschkoberg / Halámky , fir Bruck / Trpnouze , Schwarzenbach / Tušť , leg courts / Dvory nad Lužnicí , Gundschachen / Kunšach , Erdweis / Nová Ves nad Lužnicí , Abbrand / Spáleniště , Zuggers / Krabonoš , Sofienwald / Žofina Hut , Weissenbach / Vyšne and Naglitz / Nakolice (the train station in Gmünd, Lower Austria, and the two lines from Bohemia on Czech territory were now located).

- Hungary had by the Treaty of Trianon now Petržalka / Pozsonyligetfalu / Engerau, now part of the urban area of Bratislava , on the southern bank of the Danube, assign. The Czechoslovak-Hungarian border commission returned the communities of Šomošová / Somoskőújfalu and Šomoška / Somoskő (April 29, 1923) and Šušava / Susa (October 4, 1922) to Hungary.

- With Romania, in the course of the Treaty of Sévres, there was an exchange of territory in Carpathian Ukraine (1921); The area around the localities Veľká Palad , Fertešalmáš and Aklín was replaced by an area further east around the localities Bočkov (Romanian Bocicău ), Komlóš (Romanian Comlăușa ), Veľká Ternavka (Romanian Tarna Mare ), Suchý potok (Romanian Valea Seacă ) and further east south of the Tisza near Tjatschiw the place Valea Francisc / Franzensthal (now Romanian Piatra ) swapped.

Czechoslovak Republic

The official name was from 1918 to 1938 Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR, initially RČS); until 1920 short form Czecho-Slovakia. The state came from the areas of Bohemia , Moravia and Austrian Silesia, which previously belonged to Austria (now united to the country of Moravia-Silesia ), as well as from the areas of Upper Hungary (Slovakia) and Carpathian Ukraine (Podkarpatská Rus, today Oblast Transcarpathia (Ukraine) ) that belonged to Hungary ).

The philosopher and sociologist Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was elected as the first president . The first Prime Minister was Karel Kramář in his Kramář government from 1918-1919. The provisional constitution of November 1918 was passed by the Czechoslovak National Committee, which in June 1918 was composed of representatives of Czech parties according to the election results of 1911.

The constitutional charter of the Czechoslovak Republic was adopted on February 29, 1920 - not by an elected parliament , but by the Provisional National Assembly, which was formed by expanding the aforementioned National Committee. Of the 270 members of the National Assembly, 54 seats were allocated to the Slovaks. The Germans in Bohemia and Moravia, who predominantly rejected the establishment of the new state, boycotted the National Assembly and thus missed the opportunity to influence the creation of a new state.

For the city council elections of June 15, 1919, the same conditions applied to women and men for the first time. Before the separation of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic, women in Czechoslovakia were granted universal active and passive suffrage on February 29, 1920. This introduced women's suffrage at the national level. The election to the National Assembly of Czechoslovakia took place on April 18 and 25, 1920. The first parliamentary elections for the House of Representatives and Senate took place on April 18, 1920. In these elections, the right to vote for women, introduced in the constitutional charter, already applied . Czechoslovakia was the only one of the states of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe that were revolutionized or established in the interwar period in which democracy prevailed as a form of government in the long term. It remained a parliamentary democracy until it was broken up in March 1939.

Establishing an independent from Rome Czechoslovakian Church in 1920 and the collection of Hus -Todestages a national holiday in 1925 was the expenditure incurred in the 15th century conflict with the Vatican flare up again; this conflict was resolved in February 1928. Relations with the Vatican, however, remained difficult.

In 1920 and 1921 the Little Entente was founded through a series of treaties , an alliance between Czechoslovakia, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the Kingdom of Romania , which was directed against the revision policy of Miklós Horthy and against attempts at Habsburg restoration.

The revolutionary movement in Europe, sparked by the Russian October Revolution , the German November Revolution and the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic, did not stop at Czechoslovakia. In 1921 the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was founded.

After Masaryk's resignation in 1935, his closest colleague Edvard Beneš became his successor.

The period 1934-1938 brought next to an economic decline another danger, because in the border areas with predominantly Sudeten German population was Sudeten German Party of Konrad Henlein a ready breeding ground. In 1935, the construction of effective border fortifications based on the model of the Maginot Line began .

Domestic politics

Czechoslovakia was a heterogeneous entity both politically and denominationally. According to the results of the only two Czechoslovak censuses of the interwar period, the population in 1921 (1930) consisted of Czechs 51.5% (51.2%) and Slovaks 14% (15%) and a large number of Germans 23.4% (22nd , 5%) in the Bohemian countries ( Sudetenland ) and Slovakia ( Carpathian Germans ), as well as from Magyars 5.6% (4.9%) and Russians (Ruthenians) or Ukrainians 3.5% (3.9%) in the Slovakia. It should be noted, however, that the Czechs and Slovaks were given as "Czechoslovaks" in the censuses, so that in some sources differing proportions of Czechs and Slovaks can be found (for example 43% Czechs and 22.5% Slovaks), their total but does not differ from the above. The Ruthenians and Ukrainians were given as Rus (ové) .

The relationship of the ethnic groups to one another was fraught with conflict. There were several minor arguments.

- Czechoslovak Chamber of Deputies 1920–1935 - German and Hungarian parties

| Political party | Mandates 1920 | Mandates in 1925 | Mandates in 1929 | Mandates in 1935 | Voices 1935 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sudeten German Party | - | - | - | 44 | 1.256.010 |

| German National Party | - | 10 | 7th | - | - |

| German National Socialist Workers' Party | 15th | 17th | 8th | - | - |

| German Social Democratic Workers' Party | 31 | 17th | 21st | 11 | 300,406 |

| German Christian Social People's Party | 7th | 13 | 14th | 6th | 163,666 |

| Association of farmers | 11 | 24 | - | 5 | 142,775 |

| Hungarian parties

and Sudeten German electoral block |

9 | 4th | 9 | 9 | 292,847 |

| United German parties | 6th | - | 16 | - | - |

| Total (from 300 mandates) | 79 | 85 | 75 | 75 |

- Hungarian parties and Sudeten German electoral bloc (1935): German Democratic Freedom Party , German Trade Party, German National Party, Sudeten German Land Association, German Workers' Party, Spis German Party, Hungarian Christian Social Party, Hungarian National Party

The Sudeten German ethnic group lived mainly in the industrial conurbations and represented a larger ethnic group in percentage terms than the Slovaks. They were dissatisfied with their position in the state, because the invasion of Czech troops in 1918 had prevented referenda by the German minority and the annexation to Austria planned by the Sudeten Germans had been forbidden by the victorious powers . Former Austrian civil servants who did not speak Czech were dismissed, as were many heads of state-owned companies. The state language Czech was introduced as a compulsory subject in German schools (the rest of the lessons remained German). Many Sudeten Germans rejected the obligation to learn the state language, just as they persisted in a fundamental opposition to the new rulers in the 1920s, characterized by activism and negativism . After the German National Party , headed by Rudolf Lodgman von Auen, had achieved some success in the 1920 elections, its importance declined noticeably in the course of the late 1920s. The German Social Democrats were the strongest German parliamentary group in the Prague House of Representatives from 1920 to 1935, and from 1929 onwards, with their chairman Ludwig Czech , who held various ministerial posts, also became a ruling party. From 1933 onwards, large parts of the Sudeten German population were fascinated by the initial successes of German National Socialism . Konrad Henlein's Sudeten German Party , which was first striving for autonomy and emerged from the German National Socialist Workers' Party , turned to Adolf Hitler from 1937 onwards .

The Slovaks, who had not been granted autonomy within the state, were also dissatisfied, although it had been guaranteed to them by the Pittsburgh Treaty between the American Czechs and American Slovaks in May 1918. They also felt offended by the concept of the Czechoslovak nation. In 1929, one of the leading Slovak personalities, the Slovak professor Vojtech Tuka (* 1880, † 1946) was sentenced to 15 years in prison, of which he actually had to serve eight years in prison. Tuka became Prime Minister of Slovakia during World War II . At the beginning of the 20th century, Slovak and German were only allowed as foreign languages in primary schools in Hungary. Therefore there was a lack of Slovak-speaking intelligence . She was replaced by Czech teachers and civil servants whose behavior was perceived by the Slovaks as arrogant. The Czech teachers and officials contributed significantly to the Czechization of the Slovak language.

economy

In the interwar period, Czechoslovakia was one of the most progressive countries in Europe. It was one of the strongest industrial countries on the continent, with heavy industry being located in the interior of the country, while light industry predominated in the border region, which was predominantly inhabited by Germans . Above all, the country's arms production enjoyed world renown . Even before 1918, the Bohemian lands were the most industrialized area of the Danube Monarchy . However, Slovakia was economically significantly weaker than the western part of the country until the 1960s. The Carpathian Ukraine, which was annexed by the USSR in 1945 and incorporated into the Ukrainian SSR , was in 1918 a practically industrial area with a high percentage of illiterate people in the population. The Great Depression also hit Czechoslovakia from 1929 to 1933. The number of unemployed was around one million.

Broken up 1938/39

Sudeten crisis

In March 1938 the Sudeten crisis began , which was exacerbated by the provocative Karlovy Vary program of the Sudeten German Party and culminated in the Munich Agreement of September 29, 1938 (also called the Munich Diktat by the Czechs ). Czechoslovakia had to cede its entire border area to the German Reich with a predominantly German-speaking population (Sudetenland), which already happened on September 30, 1938. Hungary and Poland were allowed to make similar demands on Czechoslovakia regarding ethnically Hungarian and Polish territories, which later came about.

After the implementation of the agreement, no more than 40% of the Czech industry was left behind, an almost unfit for military service and only with difficulty economically independent remainder. In the occupied territories, expulsions and murders of Czechs as well as mass murders and deportations of Czech Jews and Sinti and Roma took place. The subsequent retaliatory actions, such as acts of sabotage by Czech resistance fighters, once again led to cruel actions by the Wehrmacht and the SS .

The Second Republic and its "liquidation" (1938/39)

President Edvard Beneš resigned from office on October 5, 1938 and went to London . In view of the chaos and the power vacuum that Beneš had left, the Slovaks declared their longed-for autonomy within Czechoslovakia a day later . This was recognized by the National Assembly one day later and enshrined in the so-called Autonomy Act on November 22nd , through which the state was appropriately renamed the Czecho-Slovak Republic . This state is also known as the Second Republic . On October 11, the first autonomous government of Carpathian Ukraine was also established.

On October 31, 1938, Hitler issued a directive on the final liquidation of Czechoslovakia and the separation of Slovakia. This guideline was subsequently implemented. On November 2nd, Slovakia lost about a third of its territory to Hungary through the First Vienna Arbitration .

In February 1939, the Germans began to officially persuade the Slovak representatives to declare an independent Slovakia. To prevent this, Czech troops occupied Slovakia on March 9th. 253 Slovaks were interned in Moravia and a new government was installed in Slovakia. On March 13, Hitler invited the Slovak Prime Minister, Jozef Tiso, who had been deposed by the Czechs, to Berlin . Practically equivalent to an ultimatum , he “recommended” that Slovakia's independence be proclaimed immediately, otherwise it would be left to Hungary and Poland. On March 14, 1939, the Slovak parliament that emerged from elections voted unanimously for independence.

With the establishment of the First Slovak Republic , a German vassal state , Czecho-Slovakia ceased to exist. One day later, on March 15, 1939, contrary to the Munich Agreement and without the consent of the other great powers , the Wehrmacht occupied what is known as the rest of the Czech Republic . This area was declared a Reich Protectorate . At the same time, contrary to the Vienna arbitration , Hungary occupied the Carpathian Ukraine (Carpathian Russia). After another attack by Hungary on March 23 in the Slovak-Hungarian war from March 23 to April 4, 1939, Slovakia lost “only” the easternmost areas of the disputed part of the country.

Foreign rule, vassal state, exile 1939–1945

protectorate

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia , established in 1939, comprised the parts of Bohemia and Moravia that were predominantly inhabited by Czechs. The government under President Emil Hácha was under the supervision of a Reich Protector. Since the protectorate, thanks to its broad industrial base, was used intensively for German armaments (at the end of the war, the protectorate supplied around a third of the German military equipment), fewer mass murders took place here than in other occupied countries east of Germany. Of the around 120,000 Jews in the Bohemian countries (including around 30,000 in the Sudeten-German border area, 90,000 in the Czech territory, which later became the Protectorate), around 78,000 were murdered by the National Socialists. There were also deportations to the Theresienstadt (Terezín) concentration camp and other labor camps outside the Protectorate. In addition, around 8,000 Czechs were murdered, around 1,700 of them during the wave of terrorism following the Heydrich assassination attempt . The exact number of victims of the Nazi regime in Czechoslovakia has not yet been clarified: research estimates between 330,000 and 360,000 victims, including around 270,000 Jews.

After the fatal assassination attempt on the deputy Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich , the National Socialists razed the village of Lidice and the hamlet of Ležáky to the ground on June 10, 1942 . All male residents were shot, women, children and old people were deported to concentration camps (over 350 dead in total). The deportation of Jews to the concentration camps continued.

Four days before the end of the war, an armed uprising broke out in Prague and other Czech cities in May 1945, culminating in the numerous actions of the Czech resistance .

Slovakia

The Slovakia , however, was (to the eastern edges of except for a small strip along Moravia Little and White Carpathians of and Javorníky Mountains ), not occupied by German troops. As a result, she only had to conclude a “protection contract” with Germany. There were no kidnappings of non-Jewish Slovaks and Roma. However , after constant pressure from Germany, the Jewish Slovaks were deported to labor camps abroad. However, after it became public what kind of camps they were in reality, the transports were stopped. But they were resumed at the end of 1944. The reason for this was the Slovak National Uprising . Many Slovaks were involved in this militarily failed, but important post-war uprising against Hitler in August 1944. Hitler had therefore decided to occupy Slovakia militarily as well.

Government in exile

Beneš founded a government in exile in London in 1940 , and he himself became president in exile. The government in exile was recognized by Great Britain , later also by the USA and the Soviet Union . With these partners, Beneš agreed to expel the Germans from Czechoslovakia during the war.

Basically, Beneš was deeply disappointed by the Western powers because of the Munich Agreement, with which they had abandoned the Czechoslovakia, allied with them, and saw the independence of Czechoslovakia in the future only secured through a close alliance with the Soviet Union. He imagined being able to establish his country between the communist east and the capitalist west with a social order of the “third way”.

Re-establishment and coup 1945–1948

This period, from the liberation to the February revolution, includes the so-called Third Czechoslovak Republic .

liberation

Czechoslovakia was largely liberated by the Red Army (it took Bratislava on April 4 and Prague on May 9, 1945), while southwestern Bohemia was liberated by the 3rd US Army ( General Patton ). The Prague Uprising broke out in the capital between May 5th and 9th . The occupation of Prague by the Red Army on May 9th also ended the fight of the Czechoslovak resistance against the Nazi regime .

Czechoslovakia was restored to almost its 1937 borders. The so-called Bratislava bridgehead near Bratislava was enlarged at the expense of Hungary. The Carpathian Ukraine was formally part of Czechoslovakia again from 1944 to 1946, but could not de facto be regained because it was occupied and claimed by the Soviet Union. In 1946 Carpathian Ukraine was completely ceded to the Soviet Union and became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic . Only the place Lekárovce remained with Czechoslovakia in 1946.

| Slovak | Ukrainian | transcription | Transliteration | Hungarian 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galoč | Галоч | Halotsch | Haloč | Gálocs |

| Palov | Палло | Pallo | Pallo | Palló |

| Batva | Батфа | Batfa | Batfa | Bátfa |

| Palaď + Komarovce | Паладь-Комарівці | Palad Komariwzi | Palad'-Komarivci | Palágykomoróc |

| Surty | Сюрте | Sjurte | Sjurte | Anger |

| Malé Rátovce | Мaлi Ратівці 1 | Mali Rativtsi | Mali Rativci | Kisrát |

| Veľké Rátovce | Вeликi Ратівці 1 | Velyki Rativtsi | Velyki Rativci | Nagyrát |

| Male Slemence | Мaлi Ceлмeнці | Mali Selmenzi | Mali Selmenci | Kisszelmenc |

| Salamúnová | Coлoмoнoвo | Solomonovo | Solomonovo | Tiszasalamon |

| Téglás | Tийглas | Tyhlasch | Tyhlaš | Kistéglás |

| Čop | Чоп | Chop | Čop | Csap |

Communists seize power

After the Second World War, the official name from 1945 to 1960 was again the Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR). At the behest of Moscow, President Edvard Beneš formed a coalition government of the “ National Front ” under Prime Minister Zdeněk Fierlinger . The Kaschau program passed on April 5, 1945 formed the basis of their work. In the Czech Republic, Beneš's public statements about the Sudeten Germans resulted in acts of revenge, mass exodus and the deportation and expulsion known as Odsun on the basis of the Potsdam Agreement and the Beneš decrees agreed by all the allies . Around three million Germans were removed from the state in 1945/1946. Originally, the removal of the Hungarian minority from southern Slovakia was also planned, but following an agreement with Hungary and the extensive withdrawal of initial attempts at resettlement to the Czech Republic in 1948, the number of Hungarians in Slovakia has only decreased slightly compared to the pre-war level.

The 1946 parliamentary elections were won by the Communists in Bohemia and Moravia with 40% and the Democratic Party in Slovakia with 62%. However, since Slovakia is significantly smaller than Bohemia and Moravia, this election result enabled the communists (who had been partially controlled from Moscow since the Second World War ) to fill key ministerial posts in the Klement Gottwald I government in Prague , then To quickly get rid of the Slovak Democratic Party in 1947 and to nationalize the economy, and finally to seize power completely in February 1948 through the February coup ( government of Klement Gottwald II ).

Beneš decrees

In the course of the restoration of the state, the so-called Beneš decrees were issued in the Beneš era . In addition to ordinary administrative matters, these also regulated the punishment, expropriation and expulsion of Germans and Hungarians, who were seen as "enemies of the state". Between the end of the war and the Potsdam population transfer resolution on August 2, 1945, around 800,000 Germans were planned and spontaneously driven across the borders into Austria and Germany in the course of the so-called wild expulsions . Many of them were also forced to flee from harassment and abuse. A legal processing of the events did not take place. The Beneš Decree 115/46 (Law on Exemption from Punishment ) declares actions up to October 28, 1945 in the struggle to regain freedom ... or which aimed at just retribution for acts of the occupiers or their accomplices ... as not unlawful. The victorious powers of World War II took on August 2, 1945 in the Potsdam Protocol , Article XIII, to the wild and collectively concrete running expulsion of the German population not position. However, they explicitly called for an "orderly and humane transfer" of the "German population segments" that "remained in Czechoslovakia". Between February and October 24, 1946, German citizens were forced to leave what was then Czechoslovakia. In Francis E. Walter's report to the US House of Representatives, it was noted that the transports were by no means in accordance with the prescribed regulations. All private and public property of the German residents was confiscated by the Beneš decree 108 . Most of the Sudeten Germans in Austria were transferred to Germany in accordance with the original transfer goals of the Allies.

The Catholic Church was expropriated in the communist era . The property of the Evangelical Church was liquidated by the Beneš Decree No. 131.

The communist era 1948–1989

Gottwald era

The re-established state, which came under the rule of the Communist Party after the February overthrow of 1948, had to submit to the Stalinist policy of the Soviet Union. Edvard Beneš resigned because he did not want to sign the new constitution of May 1948. The communist leader Klement Gottwald proclaimed a socialist republic. He became President and First Secretary of the Communist Party.

The show trials of Jihlava (Iglau) also take place at this time . The reason for this was the murder of three local communist functionaries in the Moravian village of Babice on July 2, 1951 , known as the Babice case . This crime provided an opportunity to set an example against peasants and the Catholic rural population around Moravské Budějovice , who openly rejected the new communist state doctrine. Eleven death sentences were passed in the trials and long-term penal sentences were pronounced against 111 people, which also included kinship-like disadvantages and resettlements. However, these were by no means the only show trials in the Stalinist era. In November 1952 Rudolf Slánský was sentenced to death along with eleven other defendants in the " Slansky Trial ".

The Czech parts of Bohemia and Moravia formed a unified centralized state with Slovakia until 1969. However, Slovakia was granted a certain degree of autonomy - more or less pro forma - by having its own government, the ministers of which were called Poverenik (German Commissioner). One can assume, however, that this should primarily form the extended hand of the central government in Prague (in which the Slovaks were also represented with ministerial posts). In addition to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Komunistická strana Československa, KSČ ) there was also a Communist Party of Slovakia ( Komunistická strana Slovenska, KSS ) of the same type.

Novotný era

After Klement Gottwald's death in 1953, Antonín Novotný succeeded him as party secretary, while Antonín Zápotocký took over the office of president. The wave of de-Stalinization after the 20th party congress of the CPSU got stuck in verbal assurances in Czechoslovakia, since neither the Stalinist leadership was changed, nor were the victims of the purges rehabilitated. The successor to President Zápotocký, who died in 1957, was Novotný, who now combined both offices in his hand. In 1960 a new constitution was enacted and the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) was proclaimed . The leading role of the KSČ was now enshrined in law, the centralization of the state tightened at the expense of Slovak institutions.

Prague Spring: The Dubček Intermezzo

In January 1968, Alexander Dubček was elected party leader, replacing the Stalinist Novotný, who a little later also lost the office of president to Ludvík Svoboda . Under Dubček, the Communist Party began a liberalization and democratization program in the spring of 1968, which was influenced and reinforced by the critical and reform-oriented public. The government abolished press censorship , guaranteed freedom of expression and allowed foreign travel. It also initiated economic reforms and sought to redefine the role of the Communist Party in society. This attempt to create “socialism with a human face” went down in history under the catchphrase “ Prague Spring ”.

Brezhnev Doctrine: End of Liberalization

The communist leaderships of some Warsaw Pact countries (especially the People's Republic of Poland and the German Democratic Republic ) saw this development as a threat to their position of power. Therefore, the majority of this military alliance (with the exception of Romania and Albania , which then definitively left this pact), under the leadership of the Soviet Union, decided to put an end to the reform efforts on August 21, 1968 by marching into Czechoslovakia by troops of the Warsaw Pact. The Soviet party leader Leonid Brezhnev - after initially uttering the famous sentence "This is your business" ( "Eto wasche djelo" ) to Dubček in response to his concerns - justified this by claiming that the Eastern Bloc states only had limited sovereignty if they did socialism is in danger ( Brezhnev doctrine ).

Dubček was soon ousted and replaced by Gustáv Husák , who immediately reversed Dubček's reforms, filled all leading positions in the state with supporters loyal to Moscow and carried out a "purge" of the party. In 1975 Husák was elected president as well as his position as party leader. In October 1968 there was also a constitutional reform. The Czech Socialist Republic was federalized through the creation of the new constituent states of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic .

The citizens of Czechoslovakia fell into resignation after the end of the “Prague Spring” of 1968. The state was completely sealed off to the west with border fortifications similar to those of the GDR .

From Charter 77 for autumn 1989

With Charter 77 , a civil rights movement emerged in 1977, with Václav Havel at its head, which, despite state persecution, called for political action from 1988 onwards. The events in the Prague embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany from September 1989 onwards enabled thousands of GDR citizens to leave for the West in several waves, an important preliminary stage to the fall of the Berlin Wall .

Velvet revolution

In mid-November 1989, under the impression of the changes in the socialist brother countries, which were made possible by the reform program of Mikhail Gorbachev and the so-called Sinatra Doctrine of the Soviet Union, demonstrations took place over several days in Bratislava and Prague. The initial spark was triggered on the 16th, the subsequent large-scale protests on November 17th later made this one of the country's holidays as the day of the struggle for freedom and democracy.

After days of protests, the communist leadership resigned. With this relatively peaceful and non-violent uprising of the people, the Communist Party regime ended. At the beginning of December, a predominantly non-communist government was formed under the reform communist Marián Čalfa . a. civil rights activist Jiří Dienstbier was a foreign minister. At the end of December 1989 the writer and civil rights activist Václav Havel was elected president. The first free parliamentary elections since 1945 took place on June 8, 1990. Václav Havel's citizens' forum and the Slovak public against violence, who together made up the government, were victorious .

The way in which the Czechs and Slovaks got rid of the communist dictatorship attracted worldwide attention and earned the country tremendous sympathy.

Separation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia

It soon became apparent that the federal state of "Czechoslovakia" would no longer exist in the long term. The interests of the politicians in both parts of the country were too different for that. The Czech side did not want to have to constantly provide "development aid" to Slovakia, the Slovak side did not want to be constantly patronized or outvoted from far-off Prague.

After heated debates in parliament, which have become known as the so -called war of dashes , the state name Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) was finally given on April 23, 1990, with the short forms Czechoslovakia (in the Czech Republic) and Czecho-Slovakia (in Slovakia ) accepted.

On January 1, 1991, all redistributions of budget funds from the Czech Republic to Slovakia that had been customary up to that point were ended. Each sub-state now had to get by with its own tax revenue. In May 1991 the members of the Czech parliament were negotiating the eventuality of the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. After numerous unsuccessful negotiations between Czechs and Slovaks, it was finally decided to wait until the new elections in 1992 to make a final decision on the future of Czechoslovakia.

After negotiations between the prime ministers of the Czech Republic ( Václav Klaus ) and Slovakia ( Vladimír Mečiar ) who emerged from the 1992 elections , it was decided (without consulting the people) to dissolve Czechoslovakia peacefully. On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic (Czech Republic) and Slovakia (Slovak Republic) as planned . This was not a secession , but a dismembration . In this context, the division of the previously common currency ( Czechoslovakian crown ) into two separate currencies is unique in history.

See also

- List of Presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of Prime Ministers of Czechoslovakia

- History of the Czech Republic

- History of Slovakia

- History of Carpathian Ukraine

- German-Czech relations

literature

- Bernd Rill: Bohemia and Moravia - history in the heart of Central Europe. 2 volumes, Katz, Gernsbach 2006, ISBN 3-938047-17-8 .

- Jörg K. Hoensch : History of Czechoslovakia. 3rd edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Berlin / Cologne 1992, ISBN 3-17-011725-4 (first edition 1966 under the title: History of the Czechoslovak Republic 1918–1965 ).

- Richard Lein: The military behavior of the Czechs in the First World War , dissertation at the University of Vienna 2009; Book edition: fulfillment of duty or high treason? The Czech soldiers of Austria-Hungary in World War I , Lit, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-50158-5 .

- Karl-Peter Schwarz: Czechs and Slovaks - The long road to peaceful separation. Europaverlag, Vienna / Zurich 1993, ISBN 3-203-51197-5 .

- Volker Zimmermann: A socialist friendship in transition. The relations between the Soviet Zone / GDR and Czechoslovakia (1945–1969) , Klartext, Essen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8375-0296-1 .

- Antonín Klimek : Velké dějiny zemí Koruny české. Volume 13: 1918–1929 , Paseka, Praha / Litomyšl 2000, ISBN 80-7185-328-3 (Czech).

- Antonín Klimek, Petr Hofman: Velké dějiny zemí Koruny české. Volume 14: 1929-1938 , Paseka, Praha 2002, ISBN 80-7185-425-5 (Czech).

- Zdeněk Beneš (ed.): Understanding history. The Development of German-Czech Relations in the Bohemian Lands 1848–1948. Gallery, Prague 2002, ISBN 80-86010-66-X .

Web links

- History of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia at a glance (Czech)

- Jan Palach Week, 1989: The Beginning of the End for Czechoslovak Communism , The Digital National Security Archive

- Martin Schulze Wessel : Czech Republic - Institutions, Methods and Debates in Contemporary History , Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia Contemporary History , September 19, 2011.

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.rodon.cz/admin/files/ModuleKniha/398-%C2%A6%C3%AEl-inky-zN-irodn-%C5%9Fch-novin-1848-1850.pdf

- ^ Richard Charmatz: Austria's inner history from 1848 to 1907. Volume 2, Leipzig 1912, p. 107.

- ^ Richard Charmatz: Austria's inner history from 1848 to 1907 (2nd volume), Leipzig 1912, p. 116.

- ↑ Milan Majtán: názvy obcí Slovenskej Republiky , Bratislava 1998

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original dated December 5, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Constitutional document of the Czechoslovak Republic of February 29, 1920 ( Memento of the original of March 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. at verfassungen.de

- ↑ a b Dana Mulilová: Mothers of the Nation: Women's Vote in the Czech Republic. In: Blanca Rodríguez-Ruiz, Ruth Rubio-Marín: The Struggle for Female Suffrage in Europe. Voting to Become Citizens. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden and Boston 2012, ISBN 978-90-04-22425-4 , pp. 207-223, p. 216.

- ↑ - New Parline: the IPU's Open Data Platform (beta). In: data.ipu.org. February 29, 1920, accessed September 30, 2018 .

- ^ Mart Martin: The Almanac of Women and Minorities in World Politics. Westview Press Boulder, Colorado, 2000, p. 102.

- ^ Jad Adams: Women and the Vote. A world history. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-870684-7 , page 437

- ↑ a b “Prager Tagblatt”, No. 116 of May 18, 1935, Czechoslovak parliamentary election of May 19, 1935 .

- ↑ Alena Mípiková and Dieter Segert, Republic under pressure .

- ↑ Christiane Brenner : "Between East and West". Czech political discourses 1945–1948. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 3-486-59149-5 , p. 34.

- ↑ Указ Президиума ВС СССР от 22.01.1946 об образовании Закарпатской области в составе Украинской ССР. In: Wikisource. Wikimedia Foundation, accessed June 8, 2020 (Russian).

- ^ Alfred Schickel: The expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia: history, background, reviews. Ed .: Federal Ministry for Displaced Persons and Refugees, Documentation, ISBN 3-89182-014-3

- ↑ Cornelia Znoy: The expulsion of the Sudeten Germans to Austria 1945/46 , diploma thesis to obtain the master’s degree in philosophy, Faculty of Humanities at the University of Vienna, 1995.

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Dept. Pres. 9 Media Service: Sudetendeutsche und Tschechen, Austria, Reg.Nr. 89905, p. 47.

- ^ Charles L. Mee : The Potsdam Conference 1945. The division of the booty . Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-453-48060-0 .

- ↑ Francis Eugene Walter: expellees and refugees of German ethnic origin. Report of a Special Subcommittee of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, HR 2nd Session, Report No. 1841, Washington, DC (March 24, 1950).

- ↑ Ignaz Seidl-Hohenveldern : International Confiscation and Expropriation Law. Series: Contributions to foreign and international private law. Volume 23. Berlin and Tübingen, 1952.

- ↑ Madeleine Reincke: Prague , ISBN 3-8297-1044-5 , p. 33 .