Czech-Slovak Republic

| Česko-Slovenská republika (Czech, Slovak) |

|||||

| Czech-Slovak Republic | |||||

| 1938-1939 | |||||

|

|||||

|

Motto : The truth wins! ( Czech Pravda vítězí ) |

|||||

| Official language | Czech , Slovak | ||||

| Capital | Prague | ||||

| Form of government |

Republic ( federal state or unitary state with autonomous territories) |

||||

| Head of state |

President Emil Hácha |

||||

| Head of government |

Prime Minister Rudolf Beran |

||||

| surface | 99,348 km² | ||||

| population | 10.77 million | ||||

| Population density | 94 inhabitants per km² | ||||

| Population development | 0.5 per year | ||||

| Gross domestic product per inhabitant | $ 1,850 (1939) | ||||

| currency | Czechoslovak crown | ||||

| founding | September 30, 1938 ( Munich Agreement ) and October 7, 1938 (federalization) | ||||

| resolution | March 15, 1939 | ||||

| National anthem | Kde domov můj and Nad Tatrou sa blýska | ||||

| National holiday |

October 28 (state founded in 1918) |

||||

| License Plate | Č-SR | ||||

| Area and population refer to the year 1939 | |||||

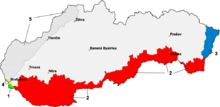

| Location and territory of Czechoslovakia from 1938 to 1939 | |||||

Czecho-Slovak Republic ( Czech and Slovak : Česko-Slovenská Republika , official abbreviation Č-SR or Czecho-Slovakia (formally not quite correct also Czechoslovakia ), unofficially also called the Second Republic ) refers to the Sudetenland , southern Slovakia and Upper Hungary and the Olsagebiet reduced Czechoslovak state, which until its destruction existed for 170 days between 30 September 1938 and 16 March 1939th

The Second Republic was the result of the events after the Munich Agreement and the Sudeten Crisis as well as the First Vienna Arbitration , in which Czechoslovakia was forced to cede the German-populated areas, i.e. the Sudetenland , to the National Socialist German Reich on October 1, 1938 , as well the southern, Hungarian-populated part of Slovakia to Hungary . In addition, Poland occupied the Olsa area and the city of Teschen .

The former unitary state of Czechoslovakia was federalized. However, federalism was asymmetrical: Slovakia and Carpathian Russia each received their own autonomous bodies with far-reaching powers; for the Czech lands ( Bohemia and Moravia - Silesia ), however, the Czechoslovak National Assembly and the central government in Prague remained responsible. One-party regimes were set up in the Slovak part of the country and in Carpathian Russia. In the Czech part of the country there were still two parties after the communists were banned, with the Strana národní jednoty (Party of National Unity) having a dominant position. With the Enabling Act of December 15, 1938, the parliamentary system was effectively abolished.

The remaining so-called remnant Czechoslovakia was split up in March 1939. The Slovak State was created ; Germany de facto annexed the Czech part of the country as the protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and Hungary the Carpathian Ukraine.

history

October to November 1938

The so-called “Second Republic” came into being on October 1, 1938 at the earliest. The first German troops of the Wehrmacht began to invade the Sudetenland . At the same time, the Czech and Jewish population began to be expelled from the border regions. Part of the population (government officials, farmers, soldiers) fled the Sudetenland because they lost their jobs. Many refugees were stopped on the run by Sudeten German Freikorps and had to give up their property. At the same time, on October 1, the clandestine transport of Karel Hynek Mácha 's remains from Litoměřice to Prague began. On October 2, 1938, the Hungarian ambassador asked when Czechoslovakia would be ready for negotiations about the Hungarian-populated areas. One day later the Sudetenland was officially attached to the German Reich and Hitler traveled to the Sudetenland. He and his management were greeted by enthusiastic Sudeten German crowds. On October 5, President Edvard Beneš abdicated and left the business of government to General Jan Syrový . On the same day, Hungarian border guards crossed the southern Slovakian border, provoking a deployment of the Czechoslovak armed forces .

On October 6, 1938, Hlinkas Slovak People's Party and other Slovak parties and politicians signed the Žilina Agreement, in which they demanded immediate autonomy and the formation of a Slovak provincial government under Jozef Tiso . The central government in Prague agreed the following day. A hyphen was then inserted between Czecho-Slovakia in the name of the republic. On October 8, Hitler instructed Foreign Minister Ribbentrop to strongly promote the new autonomy of Slovakia and Carpathian Ukraine in order to later be able to crush the Czechoslovak state. A new German party was founded in Bratislava which, like the Sudeten German Party, sympathized with the National Socialist government in the German Reich. Your leader Franz Karmasin was appointed "State Secretary for the interests of the German ethnic group" in the Slovak state government. In the Czech border areas, the violence continued and bitter fighting broke out between Czech partisans and the German Wehrmacht. An originally planned British border mission was then abandoned. On October 10th, the Germans occupied Petržalka .

On October 11, 1938, the autonomy of Carpathian Ukraine was declared final. On October 12th, the Czechoslovak army was attacked in Osekách Prachatice and suffered a heavy defeat. It was one of the many attacks carried out by the German side in 1938 to occupy the area that Germany did not get in the Munich Agreement . Nevertheless, many attacks against the Czechoslovak border troops failed. Such fighting also took place on the Hungarian side in southern Slovakia and in Carpathian Ukraine. At the same time the negotiations between Czechoslovakia and Hungary reached a low point. Despite the loss of territory, the 20th anniversary of Czechoslovakia was celebrated on October 28, 1938. On October 31, 1938, Moravian Chrostau was attacked. The Czechoslovak units were able to regain control of the place.

November to December 1938

On November 1, 1938, 6,000 refugees were temporarily quartered in railroad cars. Since many refugees had nothing left, they had to be taken care of by the state. In Slovakia and in Carpathian Ukraine, the border negotiations ended on November 2, 1938 in the First Vienna Arbitration Award . Hungarian troops occupied the south of Slovakia and part of the Carpathian Ukraine. The Second Republic was a remnant state that had lost a total of 33% of its land area and only 40% of its industry remained. Even after the annexation of the territory, the situation remained tense. The state had to organize supplies for tens of thousands of refugees from the occupied territories and received money from abroad to help.

In the Slovak part of the country, the Slovak People's Party established a one-party dictatorship . The other bourgeois parties joined her, the Social Democrats were banned (the Communists had already been banned in Slovakia on October 9th). In a similar way, the bourgeois parties of the Czech part of the country united on November 18, 1938 to form a National Unity Party ( Strana národní jednoty ) , which was led by the agrarians. Their program was a corporatist one inspired by Italian fascists. The Social Democrats and the left wing of the People's Socialists formed the National Labor Party (Národní strana práce) as a “loyal opposition”.

On November 30, 1938, Emil Hácha was elected President of Czecho-Slovakia. On December 1, 1938, Rudolf Beran , who was strongly right-wing and was skeptical of liberalism and democracy , became the new Prime Minister of the entire state . On December 15th, the National Assembly passed an enabling law that allowed the government to rule without parliament. Parliamentary democracy was thus effectively eliminated. Strict press censorship was introduced. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was dissolved and banned on December 27th. Towards the end of 1938, the Czechoslovak authorities managed to largely resolve the refugee problem and the problems of production, supply, education and finance.

In the meantime, all Czech political parties and associations in the breakaway Sudetenland have been abolished, their property has been confiscated, the Czech language has been banned and all Czech newspapers have been banned. Czech films were liquidated and books burned. Despite the guarantee by the Munich Agreement of 1938, the situation in the border areas was controversial, the Czech and German populations avoided the new common border. The German National Socialists unleashed the hunt for Jews in the border area, which culminated in November 1938 during the Reichspogromnacht . The first deportations of Czechs and Jews to the Dachau concentration camp began.

January to March 1939

January 1939 was marked by increased pressure from Germany and Hungary. On January 12th, selected units of the Wehrmacht were given the task of preparing for an attack. The new border in the south was also marked by escalating events. On January 21, 1939, Foreign Minister František Chvalkovský visited Berlin to discuss mutual relations. The official visit ended in dictation. The Slovak negotiations with Hitler began in the spring of 1939. On February 12, the Slovak politician Tuka visits Hitler. Although Slovakia threatened to split off, many politicians hoped that the Czechoslovak state could continue to exist neutrally. But the German Reich demanded gold and money from the weak state. Although the Germans built up an enormous national debt as a result, the repayment was refused. Under enormous pressure, the representatives of the Czechoslovak National Bank were finally forced to sign a contract with the Deutsche Reichsbank in which Czechoslovakia committed 465.8 million kroner to the German Empire , which later led to the state bankruptcy.

At the beginning of March 1939, the Czechoslovak government received the first information about the planned break-up of Czechoslovakia. Support from Great Britain, France or Italy was not expected. Slovakia under the Hlinka party distanced itself more and more from the Czech part of the state and began an anti-Czech campaign. The Czech-dominated government saw this as an insult and allowed Slovakia to be occupied. On March 9, the Slovak government declared a state of emergency. Leading politicians like Tiso and Tuka were dismissed and arrested for the time being. On March 11, 1939, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels announced the Reichsdruckbefehl, which marked a high point in anti-Czechoslovak propaganda. There were hectic negotiations in Prague and Bratislava ; To solve the crisis, a government loyal to the Czechs was set up without further ado. Meanwhile Jozef Tiso flew to Berlin. There he was given an ultimatum: either Slovakia would become independent or it would be divided between Poland and Hungary. Tiso refused to take such a decision alone and returned to Č-SR, where the majority of the autonomous parliament voted in favor of a declaration of independence. After Slovakia announced its independence, the Carpathian Ukraine followed a day later.

Loss of territory

1. The Sudetenland is attached to the German Reich (October 1938).

2. The Olsa area with the Czech Teschen is occupied by Poland (from October 2, 1938).

3. Areas with a Hungarian majority are reclassified to Hungary in accordance with the First Vienna Arbitration (November 2, 1938).

4. the Carpathian Ukraine is back to Hungary divided (16 to 23 March 1939). On April 4, 1939, Hungary was given back

an area in eastern Slovakia .

5. In March 1939, the rest of the Czech Republic was occupied by the Germans and, as the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, placed under the territorial sovereignty of the German Reich.

6. The Slovak Republic is (the day before) a separate state.

The Second Czechoslovak Republic had lost over 14% of its land area in the Munich Agreement and was now in a very weak state. As a result of the agreement, Bohemia and Moravia had lost around 38% of their area to the German Empire , with around 3.2 million German and 750,000 Czech residents being lost. Without the natural borders and its costly system of border fortifications , the new state could no longer be defended militarily. Hungary received 11,882 km² in southern Slovakia , according to a census of 1941 about 86.5% of the population in this area was Hungarian. Poland acquired the city of Teschen and its surroundings (approx. 906 km², approx. 250,000 inhabitants, predominantly Polish populations) and two smaller border areas in northern Slovakia, the regions of Spiš and Orava (226 km², 4,280 inhabitants, only 0.3% Poland) . In addition, the Czechoslovak government was overwhelmed with the care of the 115,000 Czech and 30,000 German refugees who fled to the remaining territory of Czechoslovakia.

Munich Agreement

Through the intermediary of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini , the Hermann Goering 's intervention, the British prime minister gave Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Edouard Daladier with the agreement to dictator Adolf Hitler consented to the incorporation of the Sudetenland , where the population was predominantly German (see. Province of German Bohemia as well as Sudetenland (province) ) and the state connection to the rest of the German-speaking area - as before the First World War - the majority wanted.

The Munich Agreement only determined the principles of evacuation, border determination and citizenship regulation. The implementation of the agreement on the cession of the Sudeten area, the definition of the borders and the modalities of the evacuation were left to an international committee.

The Munich Agreement effectively meant the end of the multinational Czechoslovakia that emerged in 1918, as other ethnic groups or neighboring states such as Poland and Hungary also took advantage of the opportunity to occupy territories, unlike Germany, however, without the consent of Great Britain and France. The latter showed understanding for the wish of the Sudeten German population, which had been ignored since 1919, and therefore saw this resolution as a partial revision of the Treaty of St. Germain or as a subsequent fulfillment of the peoples' right to self-determination . First and foremost, they wanted to prevent another war ( appeasement policy ).

First Vienna arbitration award

The negotiations with Hungary took place between October 9th and 13th 1938 in the Czechoslovak part of the twin towns of Komárno / Komárom .

The Czechoslovak delegation was headed by the Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic, Jozef Tiso , the Hungarian by Foreign Minister Kálmán Kánya and Minister of Education Pál Teleki . As a sign of goodwill, the Czechoslovak delegation offered the Hungarian delegation the transfer of the railway station in Slovenské Nové Mesto (a suburb of the Hungarian town of Sátoraljaújhely until 1918 ) and the town of Šahy ( Ipolyság in Hungarian ). Šahy was then occupied by Hungary on October 12th.

During the negotiations, the Hungarians demanded the cession of the southern Slovak territory (including) the line Devín (Thebes, Dévény) - Bratislava (Pressburg, Pozsony) - Nitra (Neutra, Nyitra) - Tlmače (Garamtolmács) - Levice (Lewenz, Léva) - Lučenec (license, Losonc) - Rimavská Sobota (United Steffelbauer village Rimaszombat) - Jelšava (Eltsch, Jolsva) - Rožňava (Rosenau, Rozsnyó) - Košice (Kassa, Kassa) - Trebišov (Trebischau, Tőketerebes) - Pavlovce (Palocz) - Užhorod ( Uzhhorod / Ungvár) - Mukačevo ( Mukachevo / Munkács) - Sevľuš ( Vynohradiv , Nagyszőllős). In the rest of Slovakia, a referendum was to take place on whether the whole of Slovakia would join Hungary.

The Czechoslovak delegation, on the other hand, offered the Hungarians the creation of an autonomous region in Slovakia and the cession of the Great Schüttinsel (Slovak Žitný Ostrov , Hungarian Csallóköz ).

When this offer was also rejected, Czechoslovakia proposed a new solution with territorial cessions, according to which as many Slovaks and Russians were to remain in Hungary as Hungarians in Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak delegation wanted to keep the most important cities in the region in question, such as Levice / Lewenz / Léva, Košice / Kaschau / Kassa, Užhorod / Uschhorod / Ungvár. However, this was also unacceptable to the Hungarian side, and on October 13, after a meeting in Budapest, Kánya declared the negotiations to have failed.

Soon after, both sides gave their consent to bow to an arbitration ruling by the great powers Germany and Italy; Great Britain and France had previously expressed their disinterest. In the meantime, not only the Hungarians but also the Slovak government worked together with Hitler. Both sides were therefore convinced that Germany would support them in particular; but the Hungarians also enjoyed the support of Italy and Poland. At the end of October, Italy convinced Germany that arbitrage should go beyond the ethnic principle and that Hungary should also get the cities of Kosice, Uzhhorod and Mukachevo.

Polish annexation of the Olsa area

Although the Olsa area was originally intended to be annexed to National Socialist Germany, Poland saw the area as Polish, especially the city of Bohumín with its large railway junction was of decisive importance for Poland. On September 28th Edvard Beneš sent a telegram to the Polish government. When the Munich Agreement came about anyway, Beneš turned to the Soviet leadership in Moscow , which had started a partial mobilization in the east, because the Soviet leadership threatened to terminate the non-aggression pact with Poland because of the alliance with Czechoslovakia.

Nevertheless, the Polish Colonel Józef Beck believed that Warsaw had to act quickly to prevent the German occupation of the city. At noon on September 30th, Poland gave Czechoslovakia an ultimatum. It called for the immediate evacuation of the Czechoslovak troops and police and gave the Prague government until that afternoon. On October 1, the Czechoslovak government submitted and accepted the ultimatum. The Polish army entered the area on the same day and General Władysław Bortnowski officially attached the area to the Polish state.

The German side was very satisfied with this annexation and used it to make Poland complicit in the destruction of Czechoslovakia. It quickly spread that Poland was partly to blame for the division of post-Munich Czechoslovakia. Warsaw, however, denied this.

The Polish side argued that Poland deserved the same ethnic rights and freedoms in the Olsa area as the German side in the Munich Agreement. The overwhelming majority of the Polish population was enthusiastic and welcomed the territorial change; it was seen as a liberation and a form of historical justice, but the enthusiasm quickly faded as the new Polish authorities withdrew many freedoms from the people. In addition, the Polish language was approved as the only official language. Czech and German were banned in public and many Czechs and Germans were forced to leave the areas. The country practiced a rapid polonization of the area, thereby disappearing everything Czech and German from the cultural or religious life. The Roman Catholic parishes in the area traditionally belonged to either the Archbishopric of Wroclaw or Olomouc (Archbishop Leopold Prečan ), Poland placed the parishes of both archbishopric in the area under Polish administration under Stanisław Adamski , the Bishop of Katowice.

When the Czech language was banned, more than 35,000 Czechoslovaks fled back to their homeland. The behavior of the new Polish authorities, although different, was similar to the pre-1938 Czechoslovak system. The two political parties, the Socialists and the Right, were both loyal to the new Polish state. Still, left-wing politicians were discriminated against and excluded from the new authorities. The majority of the population felt more and more discriminated against by the authorities and reintegration into the Č-SR became more and more popular. However, the new area remained part of Poland for only eleven months.

politics

The country's political system was in crisis. After the resignation of Edvard Beneš on October 5, Emil Hácha was elected as the new president on November 30, 1938 . On December 1, 1938, Hácha appointed Rudolf Beran, the leader of the Peasant Party , as Prime Minister of the country ( Rudolf Beran I government ). He was more right-wing and skeptical of the new democracy. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia was dissolved and banned by him and for fear of its aggressive neighbors, although its members were allowed to remain in parliament. The so-called Enabling Act allowed the government to rule without parliament and censorship of freedom of the press and the media was introduced.

Federalization of the state

Slovak autonomy

According to the Constitutional Law No. 299/1938 Coll. the autonomy of Slovakia was enshrined in law on November 22, 1938 and passed by the National Assembly. The law came into effect on November 25, 1938. The original draft of the constitutional law came from the HSĽS . At the same time, on November 25th, as part of the law, a hyphen was inserted between the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic in the country's name . After the entry into force of this law, Czechoslovakia became a modern federation. The declaration of independence of Slovakia in March 1939 meant a breach of this law. According to Section 30 of the Constitutional Charter of the Czechoslovak Republic, a three-fifths majority of all members was necessary for the adoption of such a law. 144 MPs (it took 180) and 78 senators in the Senate (it took 90) voted for the adoption of the Constitutional Law on the Autonomy of Slovakia. Although the required number of votes was not met, the law was passed anyway and by Jan Syrový , Jozef Tiso , Josef Kalfus , Pavol Teplanský , Stanislav Bukowski , Matúš Černák , Vladimír Kajdoš , Ferdinand Ďurčanský , Karel Husárek , Ján Lichner , Ladislav Karel Feierabend , Imrich Karvaš , Petr Zenkl , Augustin Woloschin , Hugo Vavrečka , František Chvalkovský , Julian Révay , Jan Černý and Edmund Bačinský .

Autonomy of the Carpathian Ukraine

The Constitutional Law No. 328/1938 Coll on the autonomy of the Carpathian Ukraine came into force on November 22, 1938 and granted the Carpathian Ukraine full autonomy. The autonomy granted the Ukrainians - unlike the Slovaks - complete self-government of the area, in return the part of Czechoslovakia had to swear allegiance. The law was supposed to give Carpathian Ukraine the broadest autonomy in Czechoslovak history . The original text was written in Ukrainian and was a proposal by the Ukrajinské národní sjednocení , which envisaged an autonomous part of the country under their leadership. On December 12, 1938, the text was published and all the old parties - the Ruthenian Peasant Party, the Russian National Autonomous Party, the Carpathian-Russian Party of Workers and Small Peasants, and the Autonomous Agricultural Union - were united in the Ukrajinské národní sjednocení. After Slovakia declared itself independent, the Carpathian Ukraine Autonomy Act did not expire. When Carpathian Ukraine nevertheless declared itself independent, the law was repealed. For the adoption of the constitutional law, as with Slovakia, enough votes were needed: 146 members of parliament (it took 180) and 79 senators in the Senate (it took 90).

As a result of the adoption of the Constitutional Law, Carpathian Ukraine was renamed Carpato-Ukraine and received its own state symbols and an autonomous parliament in Khust , under the leadership of Avgustyn Volozhyn .

Enabling Act

According to the Constitutional Law No. 330/1938 Coll. Law and instruction to amend the constitutional charter and the constitutional law of the republic were authorized to the government in January 1939 without being able to rule the parliament and implement changes to the traditional constitution . With the adoption of the law by Beran and Hácha, the first enabling law (Act No. 95/1933 Coll.) Also severely restricted trade and abolished freedom of the press . This created a right-wing conservative state, similar to many other European states, and turned away from democracy .

Foreign policy

After the Munich Agreement, Č-SR terminated its alliance treaty of January 25, 1924 with France and Great Britain, and after the Polish annexation of the Olsa area in October, relations with the Second Polish Republic froze . The country's new foreign minister, František Chvalkovský , spoke out in favor of rapprochement with Germany, partly under pressure from Hitler. But Germany's aggressive foreign policy forced the Second Republic to freeze relations with the Soviet Union . This was followed by the Soviet denunciation of the alliance with Czechoslovakia . With the First Vienna Arbitration Award, relations with Hungary, which had been strained for years, reached a low point and Italy was disappointed. The Czechoslovak state fell into foreign policy isolation and, as a result of the Romanian and Yugoslav humiliation after Hungary's annexation, broke off relations with the two allies, but without the alliance being dissolved. As a result, Romania and Yugoslavia refused to repay the money borrowed from the Czechoslovak National Bank . The Č-SR reacted indignantly and there was a Czechoslovak military provocation on the border with Romania. Switzerland also broke off relations, presumably out of fear of Germany. It froze the bank accounts of all rich Czechoslovaks. In January to February 1939 there were renewed blackmail attempts by Nazi Germany and Czechoslovakia gave the state loans amounting to billions. The aim was to save Č-SR, because the population's wish to be able to continue to exist neutrally was widespread and shared by the government at the highest level. As on 15/16. March 1939, when Czechoslovakia was broken up, most European countries accepted this and even sympathized with the German Reich . Territorially, Hungary and the German Empire benefited from the break-up of the country. Hungary and the German Empire also benefited economically or politically, but also Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia. In Great Britain and France, Beneš's efforts to restore Czechoslovakia militarily within a very short period of time were ignored; instead, the new Slovak state was later recognized by all European allies and the Axis powers.

Domestic politics

The country's domestic politics were strongly influenced by ethnic tensions (see below). The official language Czechoslovakian with its two variants was deleted from the constitution and replaced by the two languages Czech and Slovak , and Ukrainian became the third official language. In addition to this change, a hyphen was inserted in the traditional country name Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) Czecho-Slovak Republic (Č-SR) and the license plate ČSR became Č-SR . The autonomy for Slovakia and Carpathian Ukraine, which had been planned before the Munich Agreement, was officially declared legally binding in October 1938 and turned the state into a federation of three parts of the country with five historical countries and two sub-republics with an autonomous parliament. The number of parties in the First Republic , which consisted of around 24 parties, was limited to six large parties through numerous mergers. There were also major changes in the population of Č-SR, so in October 1938 the Ukrainians became the third titular nation in the country, with the proportion of minorities falling by 510,000 to 750,000. The Germans remained the largest minority with 340,000 people. The Jewish population group consisted of 330,000 people and fell to 115,000 people by February 1939, the reason for this was the strong anti-Semitism and the numerous anti-Jewish campaigns. The 4,000 Poles and 14,000 Romanians were often subjected to Czechoslovak harassment or acts of violence as a result of the foreign policy humiliation of their home countries. During the short period of the Second Republic's existence, the Hungarian minority was Czechoslovakized and their language was banned in schools and in public life. The Polish and Romanian languages were also banned from the public. In the two sub-republics of Slovakia and Carpathian Ukraine, the situation became more and more tense. The fear of becoming Hungarian again was great and so the two autonomous governments worked firmly together with the German Reich, which in turn aroused the earlier tensions with the Czech part of the country. In addition, there were foreign influences that ultimately led to the fall of Czechoslovakia. In February the situation at the eastern end of the country became very critical, as on February 12, 1939 the Ukrajinské národní sjednocení won the absolute majority of the votes with approx. 92.4%. As a result, the Ukrainian national consciousness was again strengthened and Ukrainian acts of sabotage occurred on Czechoslovak territory. On March 15, 1939, the Parliament of the Autonomous Republic, in response to Slovakia's declaration of independence, declared the new Republic of Carpathian Ukraine to be fully independent. The parliament unanimously adopted the declaration of independence of the Carpathian Ukraine and the Č-SR occupied the two new states in response to this on March 16 and re-annexed them for a short time. After the German invasion (see below) the Ukrainians and Slovaks tried to drive out the Czechoslovak troops in order to become completely independent. However, this was only possible for Slovakia, which later called itself the Slovak State .

Political parties in the Second Republic

She represented the government side and was nationalist in orientation. Its chairman was Rudolf Beran. The party emerged from the union of all the Czech political parties of the time, with the exception of ČSDSD , the Communist Party and the ČSNS . The core of the party was the former Republican Agriculture and Agriculture Party . After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, the party disappeared.

It was an opposition left party. It consisted of the ČSDSD and part of the ČSNS . The chairman of the party was Antonín Hampl . The party represented the opposition to the ruling party and defended the principles of parliamentary democracy.

- Hlinkas Slovak People's Party - Party of Slovak National Unity

After the bourgeois parties had gone up in the Hlinka party and left and Jewish parties had been banned, it was the only party permitted for ethnic Slovaks and had a clerical nationalist orientation.

Party of the Carpathian German minority in Slovakia. It represented the local branch of the German NSDAP.

Party of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia.

It was the only party in Carpathian Ukraine and consisted of the parties of the Autonomous Agricultural Union, the Carpathian-Russian Party of Workers and Small Peasants, the Russian National Autonomous Party and the Ruthenian Peasant Party. The party was led by Avgustyn Volozhyn and on March 15 proclaimed the independence of Carpathian Ukraine.

population

In January 1939, the Second Republic had 10.77 million inhabitants. According to one estimate, the Czechs formed the largest group with seven million members in 1939 , followed by the Slovaks with 2.4 million. Czechs and Slovaks were not recorded separately until 1938. Ethnic minorities were still strongly represented despite the official end of the multinational Czechoslovakia. There were still 330,000 Jews and around 340,000 Germans . While the other minorities declined, the Romanian minority in Č-SR grew . In addition to the 10.77 million inhabitants, the republic had over 260,000 refugees.

| Ethnic group | Residents |

|---|---|

| Czechs | 7,000,000 |

| Slovaks | 2,400,000 |

| Ukrainians | 510,000 |

| German | 340,000 |

| Jews | 330,000 |

| Hungary | 100,000 |

| Roma | 32,000 |

| Romanians | 14,000 |

| Poland | 4,000 |

| Others and foreigners | 14,714 |

| All in all | approx.10,770,000 |

Refugees and displaced persons

After the implementation of the agreement, over 110,000 Czech and 30,000 German refugees or displaced persons reached the rest of the territory of Czecho-Slovakia. About 70,000 Slovaks and 10,000 Ukrainians came from Hungary and the Slovak and Ukrainian areas annexed during the First Vienna Arbitration, and another 40,000 refugees came from the areas occupied by Poland. Most of the many refugees and displaced persons settled in Bohemia in the Second Republic , around 45,000 settled in Moravia and 15,000 in the rest of the Czech Republic , although housing was scarce and around a third of the refugees remained homeless. Most of the 120,000 refugees from the remaining areas settled in Slovakia, only around 5,000 people returned to Carpathian Ukraine .

The care of the refugees was mainly organized by the Czech-Slovak Church , which received financial donations from the Vatican .

anti-Semitism

The humiliating Munich Agreement led to a radical break with the democratic tradition of the First Republic and to a change in government. The new authoritarian-nationalist-oriented government began a violent anti-Semitic campaign. The now autonomous Slovakia was dominated by the predominantly Catholic and anti-Semitic Slovak People's Party Hlinkas . There were anti-Jewish laws and campaigns in all three parts of Czechoslovakia. As a result, many Jews were excluded. Nevertheless, the Czechoslovak authorities took in 15–20,000 Jewish refugees from the Sudetenland . The emerging Czech anti-Semitic wave was weakened by France and Great Britain , which provided funding to encourage Jewish emigration from Czechoslovakia. Because the great western powers doubted the continued existence of Czechoslovakia after the Munich Agreement. In December 1938 the first Jews left Czecho-Slovakia and triggered a wave of emigration in which over 185,000 Jews emigrated by the end of February 1939. Czechoslovakia provided financial support for most of the exit applications.

Second Republic Armed Forces

The Czechoslovak army left the Sudeten areas and began to establish new state borders. Despite the bad situation in the republic, it was upgraded to 1.5 million men.

economy

The economic consequences of the Munich Agreement were felt strongly. Over 60% of industry and economic output were lost. The Czech part of the state lost around 40% of its industry, which was mostly in the Sudetenland . As a result of the Vienna arbitration, Slovakia lost its oil fields and a large part of the industry, which was mostly located in Kosice . With the loss of Mukachevo and Uzhhorod, the Carpathian Ukraine also lost its small economic center and could no longer deliver wood to the other two parts. As a result of the failure of industry, the number of unemployed rose sharply, so in January 1939 there were about 300,000 unemployed, most of whom were fugitives. The infrastructure also changed and there was only one major rail connection in the Second Republic. It took nine hours from Prague to Khust and was repeatedly cut and destroyed by Ukrainian nationalists of the Carpathian Sich. Although the economic situation was bad, almost all private companies were spared nationalization and agriculture flourished briefly. Many Jews who emigrated from Czechoslovakia left the business to their Czech deputies or trusted people. The German and Hungarian minorities had a hard time finding work, in contrast to the Polish and Romanian minorities who were cared for by the mother country.

Ethnic tensions

The severely weakened Czechoslovak Republic had to make great concessions to the country's population. After the Munich agreement moved the Czechoslovak army parts of their units, originally in the Czech Republic were in the Slovak Republic to the obvious attempts of Hungary to take over Slovakia to defeat.

The Czechoslovak government accepted the agreement of the autonomy of its state with all other parties, which the Slovak government was striving for, only the Slovak Social Democrats wanted a firm relationship with their partner Czech Republic. Jozef Tiso was nominated as a head of the new autonomous state. The only joint ministries that remained were those for National Defense, Foreign Affairs and Finance. As part of the deal, the country name was officially renamed from Czechoslovakia to Czecho-Slovakia. Likewise, the two large factions of Carpathian Ukraine , the Russophiles and Ukrainophiles, agreed on the establishment of an autonomous government, which was established on October 8, 1938. As modern Ukrainian national consciousness spread, the pro-Ukrainian faction, led by Avgustyn Volozhyn , took control of the local government and changed the name Carpathian Ukraine to the Republic of Carpatho -Ukraine .

On October 17, Hitler received Ferdinand Ďurčanský , Franz Karmasin and Alexander Mach . On January 1, 1939, the first Slovak State Assembly was opened. On January 18, the first elections to the Slovak Assembly took place, in which the Slovak People's Party received 98% of the vote. On February 12, Vojtech Tuka and Karmazin met with Hitler, and on February 22, during his presentation to the Slovak government , Tiso proposed the formation of a new independent Slovak state. On February 27, the Slovak government was tasked with the Slovakization of the Czech-Slovak units in Slovakia and opened an autonomous Slovak embassy in Berlin.

The disputes continued until March 1, 1939, when the Czechoslovak government asked for an independent Slovak state. There were some differences of opinion between Tiso and other Slovak politicians. This time the National Assembly took place in Bratislava to discuss the matter with Tiso. This almost caused a split in parliament. On March 6, the Slovak government announced its loyalty to the second Czecho-Slovak Republic and its wish to remain part of the state.

But at a meeting with Hermann Göring on March 7th, Ďurčanský and Tuka were forced to declare their independence from the Czechoslovak state. After their return two days later, the Hlinka Guard was mobilized, which in turn forced Hácha to react strongly and to pronounce martial law in Slovakia.

Liquidation of the Second Republic

In January 1939 negotiations between National Socialist Germany and Poland were broken off. Hitler announced a German invasion of Czechoslovakia on the morning of March 14th. In the meantime, the Slovak People's Party was negotiating with the Kingdom of Hungary and its representatives on behalf of the Hungarian minority in Slovakia in order to prepare for the pre-invasion of the Second Czechoslovak Republic. As of February 1939, seven army corps were assembled waiting for the invasion. The hope of being called for help by the Slovaks was not fulfilled. After the occupation of autonomous Slovakia on March 9, 1939 by Czech troops, Hitler urged the deposed Slovak Prime Minister Jozef Tiso , who had been appointed to Berlin on March 13, to sign a prefabricated Slovak declaration of independence, otherwise the Slovak territory would be divided between Poland and Hungary. Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop reported that Hungarian troops were already approaching the Slovakian border. However, Tiso refused to take this decision alone and was therefore allowed to consult with members of the Slovak Parliament.

The next day, March 14th, parliament met and unanimously decided to declare Slovakia independent. On the same day, the Parliament in Bratislava read out the Slovak Republic's independence manifesto.

In the meantime, a campaign has been staged in the German press, in which there was talk of the “Czech terror regime” against Germans and Slovaks. Hitler set the entry of German troops for March 15 at 6 a.m. On March 13th, Hermann Göring was ordered back from his vacation spot San Remo to Berlin by letter from Hitler, where he arrived on the afternoon of March 14th. The now independent Slovak Republic "placed itself under the protection of the Empire"; henceforth it was a satellite state of National Socialist Germany. At six o'clock on March 15, the German troops advanced across the border and reached the capital Prague around nine o'clock in the snowstorm. The majority of the population accepted the invasion faint or angry, only the German minority and a small layer of Czech citizens welcomed it. The German army disarmed the Czech army. The Secret State Police (Gestapo) moved in with the Wehrmacht and began persecuting German emigrants and Czech communists. Several thousand people were arrested during this action, which became known as the "Operation Grid". Hitler left Berlin at eight o'clock, arrived in Prague in the evening and spent the night on the Hradschin.

On March 16, he announced that Czecho-Slovakia had ceased to exist. The Bohemian-Moravian Lands had been reinserted into their old historical surroundings. A simultaneously published decree proclaimed that now under German territorial sovereignty standing and the Reich Protector Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath assumed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia .

The Hungarian invasion of the Carpathian Ukraine met with greater resistance, but this was quickly put down by the Hungarian army.

Independent Czechoslovakia collapsed in the wake of foreign aggression, ethnic divisions and internal tensions. Although the Czechoslovak army capitulated, the government did not; it continued to exist in exile .

See also

swell

- William L. Shirer : Rise and Fall of the Third Reich . (Touchstone Edition) Simon & Schuster, New York 1990.

- Documentation for the history of Československé politiky 1939–1945. Volume 2. Prague 1966, pp. 420-422.

literature

- Jan Gebhart, Jan Kuklík: Druhá republika 1938–1939. Svár demokracie a totality v politickém, společenském a kulturním životě. Paseka, Prague / Litomyšl 2004, ISBN 80-7185-626-6 .

- Jan Gebhart: The Second Republic 1938–1939. Discord between democracy and totalitarianism. Prague 2004, ISBN 80-7185-626-6 .

Web links

- Claudia Prinz: The "smashing of the rest of the Czech Republic" on LeMO

- Jürgen Langowski: The smashing of Czechoslovakia. In: NS-Archiv.de

- Sixty years ago: «Those who go on pilgrimages abroad…» - Swiss reactions to the destruction of Czechoslovakia. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung No. 61 of March 15, 1999 (online at haGalil , April 9, 1999)

- Robert Schuster: Land of fear and emerging anti-Semitism. The second republic. In: Radio Praha , April 17, 2010

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, p. 186.

- ↑ Jörg K. Hoensch: The constitutional structure of the ČSR and the Slovak question. In: Karl Bosl: The democratic-parliamentary structure of the First Czechoslovak Republic. Oldenbourg, Munich 1975, p. 83 ff., Here p. 113.

- ^ RM Caplin, Czechoslovakia Today 1939 .

- ↑ Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995), East-Central European Economies in Transition, ME Sharpe , ISBN 1-56324-612-0 .

- ^ A b Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, p. 183.

- ↑ Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, p. 187.

- ↑ Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, p. 188.

- ↑ Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, p. 189.

- ↑ Ladislav Lipscher: Constitution and political administration in Czechoslovakia, 1918–1939. Oldenbourg, Munich 1979, pp. 190-191.

- ↑ Ralf Gebel: “Heim ins Reich!” Konrad Henlein and the Reichsgau Sudetenland (1938–1945) . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-486-56468-4 .

- ↑ Heiner Timmermann : The Munich Agreement. In: Heiner Timmermann et al. (Ed.): The Beneš Decrees: Post-War Order or Ethnic Cleansing: Can Europe Provide an Answer? Lit Verlag, Münster 2005, p. 149.

- ↑ Československá vlastiveda , section Politika

- ↑ Československá vlastiveda , section “Politika”.

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original dated December 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Petr Brod, Kateřina Čapková, Michal Frankl: Czechoslovakia. In: The Yivo Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (English, section “Antisemitism”).