Slovak state

| Slovenský štát Slovenská republika |

|||||

| Slovak State Slovak Republic |

|||||

| 1939-1945 | |||||

|

|||||

|

Motto : sebe Verni, napred Svorne! "Be true to yourself, forward united!" |

|||||

| Official language | Slovak | ||||

| Capital | Bratislava | ||||

| Form of government | Republican corporate state | ||||

| Government system |

1939–1942: one-party dictatorship 1942–1945: one-party regime with a presidential dictatorship |

||||

| Head of state |

1939–1942: President 1942–1945: "Fuhrer and President" |

||||

| Head of government |

Prime Minister :

|

||||

| surface | 38,002 (1939) 38,055 (1940) km² |

||||

| population | 2,653,053 (1940) | ||||

| currency |

Koruna slovenská (1 Ks = 100 halierov) |

||||

| founding | March 14, 1939 | ||||

| resolution |

April 4, 1945 (de facto) May 8, 1945 (de jure) |

||||

| National anthem | Hey, Slováci | ||||

| License Plate | SK | ||||

| Location of Slovakia (green) in Europe, 1942 | |||||

The Slovak State ( Slovak Slovenský štát ) or the Slovak Republic (sloak. Slovenská republika ), since 1993 sometimes also known as the First Slovak Republic or First Slovak State ( sloak . Prvá slovenská republika or Prvý slovenský štát ), designates one under pressure from the German Empire of the Czecho-Slovak Republic cleaved landlocked country in Central Europe , which existed from 1939 to 1945. It comprised present-day Slovakia with the exception of the southern and eastern areas and bordered Germany and Hungary and, for a short time, Poland and the Generalgouvernement .

It is considered to be the first national state of the Slovaks in modern history. At the same time he was a dictatorship of the ruling alone Hlinka party , the Slovak Republic as an ally of the Axis powers on the German wars of aggression against Poland and the Soviet Union took part, racial laws adopted and in 1942 with the deportation of most of its Jewish population in German death camps and the Holocaust involved. The extent to which Slovakia can be regarded as a simple satellite state of the German Reich from 1939 to 1945 is the subject of scientific debates, since the “Third Reich” had a limited influence, especially in Slovak domestic politics.

In August 1944, as a reaction to the invasion of the Wehrmacht, a rebellion organized by parts of the Slovak army against the German occupying power and the Slovak collaborative government ( Slovak National Uprising ) broke out, which lasted until October 1944. By April 1945 Slovakia was liberated by the Red Army and then incorporated into the re-established Czechoslovakia.

State name

The official state names were:

- March 14, 1939-21. July 1939: Slovak State (Slovak Slovenský štát )

- July 21, 1939-8. May 1945: Slovak Republic (Slovak Slovenská republika )

After the declaration of independence on March 14, 1939, Slovakia was temporarily officially referred to as the Slovak state . This state name can be found in legal pronouncements as well as international treaties. With the adoption of the constitution on July 21, 1939, the state name Slovak Republic was established. The name Slovak Republic came from the fact that, according to the constitution, the new state had a republican form, and there was also the hope of being recognized by as many states as possible. However, this official state name only dominated on official documents, banknotes and coins. In public life, the term “Slovak State” was used far more frequently to emphasize the idea of statehood. The term independent Slovak state (Slovak: samostatný Slovenský štát ) was also regularly used by the ruling politicians .

In the histories of communist Czechoslovakia, the independent Slovakia from 1939 to 1945 was pejoratively referred to as the so-called Slovak State (Slovak: takzvaný Slovenský štát ). After Slovakia became independent again on January 1, 1993 under the state name Slovak Republic , the Slovak Republic began to be referred to as the First Slovak Republic from 1939 to 1945 in order to distinguish it from the current, i.e. Second Slovak Republic .

However, the name First Slovak Republic is controversial. Today's Slovakia is not considered to be the official successor state of the state structure from 1939 to 1945. The main reason for this is that present-day Slovakia sees itself as a parliamentary democracy with a pluralistic multi-party system. In contrast, according to the constitution, the Slovak state was a republic organized as a corporative state with a one-party system , in which elements of fascism were also present.

Founding of the state

After the contractually agreed cession of the Sudeten German territories to Germany in the Munich Agreement , Czechoslovakia also lost the southern regions of Slovakia, which were mostly populated by Hungarians, as a result of the First Vienna Arbitration to Hungary. On November 22, 1938, a constitutional amendment granted two parts of Czechoslovakia autonomy and their own state government: Ruthenia (now Karpato-Ukraine ) and Slovakia. Czechoslovakia was thus effectively transformed into a federal state, which was now called the " Czecho-Slovak Republic ". Germany planned a partial annexation of the territory of the " rest of the Czech Republic ". There were initially several plans for Slovakia; Official sources gave the impression through falsified information that the Slovaks wanted to belong to the Kingdom of Hungary again (their country, as " Upper Hungary ", was part of the Empire of St. Stephen's Crown until 1918 ). In the end Germany decided to let Slovakia emerge as an independent state with strong German influence and to use its military potential for the attack on Poland and other areas.

On March 13, 1939, the Prime Minister of the Slovak government, Jozef Tiso , who had been deposed by the Prague government shortly before, was invited to Berlin by Adolf Hitler . He was pressured and should immediately proclaim an independent Slovak state , otherwise the Slovak territory would be divided between Poland and Hungary . In order to make this statement more convincing, Joachim von Ribbentrop underpinned the whole thing with a falsified report, according to which Hungarian troops were already approaching the Slovakian border. However, Tiso refused to make this decision on his own and was therefore allowed to hold a meeting with the members of the Slovak national parliament . The next day, March 14th, it met and unanimously decided, after hearing Tiso's report on his conversation with Hitler, that the country should be independent; Ultimately, however, it was Hitler's directives alone that determined the establishment of an independent Slovak state on March 14, 1939. Jozef Tiso was also appointed as the new Prime Minister of the Republic.

Pressburg ( Bratislava ) became the capital with over 120,000 inhabitants at that time.

population

85% of the population were Slovaks , the remaining 15% were Germans , Hungarians , Jews or Roma . 50% of the population were employed in agriculture .

politics

Main features

The state took over the legal system of Czechoslovakia and changed it only slightly. The Constitution (adopted on 21 July) from 1939, according to was the President , the head of state , the Parliament of the Slovak Republic , which was elected for five years, the highest legislative was organ (there were, however, no national elections), and the State Council exercised the duties of a Senate (comparable to the German Bundesrat ). The government consisted of eight ministries.

Overall, the Slovak Republic was an authoritarian state characterized by many elements of fascism . In what was later to become a federal state under the socialist name of the ČSSR , it was primarily perceived as a clerical-fascist state; Statehood, which at the beginning clearly arose from the will of the majority of the Slovak population, also enjoyed the unanimous support of the Catholic clergy . However, this characterization is still used today by mostly non-Slovak historians . The constitution , passed on July 21, 1939, was based on the bourgeois-democratic constitutional type, but also adopted authoritarian-fascist notions of order - unity party , excessive emergency ordinance law, strike ban, State Council - and combined both in a Christian-social world concept.

The leading political party was Hlinkas Slovak People's Party - Party of Slovak National Unity by Jozef Tiso. There were also the parties of the national minorities. For the Hungarians it was the United Hungarian Party of János Esterházy and for the Germans the German Party of Franz Karmasin . Other parties, with the exception of these, were banned (the ban on the other parties existed before the republic was founded).

The creation of the state had positive effects on the Slovak economy, science, education and culture. The Slovak Academy of Sciences was founded in 1942 , a large number of new colleges and higher schools were established, and Slovak-language literature and culture experienced an upswing.

Anti-Semitic Politics

A number of anti-Semitic laws were passed by the government, including the Jewish Code . They completely excluded Jews from public life and later also favored their deportation to the German concentration camps . With Slovak support, tens of thousands of them were murdered there as part of the Holocaust : in 1942, almost 57,600 Slovak Jews were deported; the 30,000 Jews remaining in Slovakia according to official information worked in the camps or as "economically important Jews". From 1943 onwards, the mood in the population shifted, so that the Slovak government ordered the deportation to cease, not least due to pressure from the Vatican envoy. However, when the Wehrmacht occupied the country in August 1944, deportations began again, through which more than 12,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, Theresienstadt or Sachsenhausen.

Minister of State

The Council of Ministers of the First Slovak Republic in 1939–1945:

- March 14, 1939 - October 27, 1939 (Jozef Tiso government)

- Prime Minister: Jozef Tiso

- Vice Prime Minister: Vojtech Tuka

- Minister of the Interior: Karol Sidor , on leave from March 15, 1939, replaced on April 18, 1939, successor Jozef Tiso

- Foreign Minister: Ferdinand Ďurčanský

- Defense Minister: Ferdinand Čatloš

- Minister of Finance: Mikuláš Pružinský

- Minister for Education and National Awareness: Jozef Sivák

- Minister of Justice: Gejza Fritz

- Minister of Economy: Gejza Medrický

- Minister of Transport and Public Works: Július Stano

- October 27, 1939 - September 5, 1944 (Vojtech Tuka government)

- Prime Minister: Vojtech Tuka

- Vice Prime Minister: Alexander Mach from August 17, 1940

- Interior Minister: Ferdinand Ďurčanský , from July 29, 1940 Alexander Mach

- Foreign Minister: Ferdinand Ďurčanský, from July 29, 1940 Vojtech Tuka

- Defense Minister: Ferdinand Čatloš

- Minister of Finance: Mikuláš Pružinský

- Minister for Education and National Awareness: Jozef Sivák

- Minister of Justice: Gejza Fritz

- Minister of Economy: Gejza Medrický

- Minister of Transport and Public Works: Július Stano

- September 5, 1944 - April 4, 1945 (Štefan Tiso government)

- Prime Minister: Štefan Tiso

- Vice Prime Minister: Alexander Mach

- Interior Minister: Alexander Mach

- Foreign Minister: Štefan Tiso

- Defense Minister: Štefan Haššík

- Minister of Finance: Mikuláš Pružinský

- Minister for Education and National Awareness: Aladár Kočiš

- Minister of Justice: Štefan Tiso

- Minister of Economy: Gejza Medrický

- Minister of Transport and Public Works: Ľudovít Lednár

Administrative division

- Administrative division into 6 counties / districts (“župy”), 61 districts ( okresy ) and 2,659 municipalities

The following counties existed on January 1, 1940 (Slovak župy ):

- Bratislava County (Slovakian Bratislavská župa ; 3,667 km², 455,728 inhabitants)

-

Neutra County (Slovak. Nitrianska župa ; 3,546 km², 335,343 inhabitants)

- 5 districts (Slovak okresy ): Hlohovec , Nitra , Prievidza , Topoľčany , Zlaté Moravce

-

Trenčian County (Slovak. Trenčianska župa ; 5,592 km², 516,698 inhabitants)

- 12 districts (Slovak: okresy ): Bánovce nad Bebravou , Čadca , Ilava , Kysucké Nové Mesto , Myjava , Nové Mesto nad Váhom , Piešťany , Považská Bystrica , Púchov , Trenčín , Veľká Bytča , Žilina

-

Tatra County (Slovak. Tatranská župa ; administrative seat Ružomberok , 9,222 km², 463,286 inhabitants)

- 13 districts (Slovak okresy ): Dolný Kubín , Gelnica , Kežmarok , Levoča , Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš , Námestovo , Poprad , Ružomberok , Spišská Nová Ves , Spišská Stará Ves , Stará Ľubovňa , Trstená , Turčiansky Svý

-

Sharosch-Semplin County (Slovak. Šarišsko-zemplínska župa ; administrative seat Prešov , 7,390 km², 440,372 inhabitants)

- 10 districts (Slovak okresy ): Bardejov , Giraltovce , Humenné , Medzilaborce , Michalovce , Prešov , Sabinov , Stropkov , Trebišov , Vranov nad Topľou

-

Gran County (Slovakian Pohronská župa ; administrative seat Banská Bystrica , 8,587 km², 443,626 inhabitants)

- 12 districts (slovak. Okresy ): Banská Bystrica , Banská Štiavnica , Brezno nad Hronom , Dobšiná , Hnúšťa , Kremnica , Krupina , Lovinobaňa , Modrý Kameň , Nová Baňa , Revúca , Zvolen

The areas of the individual counties included those of the counties in Czechoslovakia that existed from 1923 to 1928, the division of which was decided on July 25, 1939 by the Slovak parliament.

International Relations

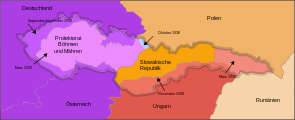

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the Slovak Republic 1939

The first Slovak Republic was recognized internationally both by the German Reich and by those states that were friendly towards Germany or at least neutral in the beginning. These were: United Kingdom , Italy , Japan and its puppet states Manchukuo and Mengjiang as well as the Provisional Government of China , the Soviet Union , Spain , Croatia , Lithuania , Estonia , Switzerland , El Salvador , the Vatican and Hungary . Even France fell into line with those a total of 27 countries that joined the newly independent Slovakia a de facto and soon pronounced the de jure recognition.

Since its inception, the republic was heavily dependent on the benevolence of the German Empire in a satellite relationship. The German-Slovak protection treaty signed on March 23, 1939 and the protection zone statute of August 28 of the same year with Germany bound the country as a "protection state" from a military, economic and foreign policy point of view to the neighboring state, which by means of advisory delegations in the Slovak ministries had extensive synchronization carried out. Thereby it became a member of the Axis Powers and was thus also involved in the wars against Poland and the Soviet Union ; Slovakia declared war on Great Britain and the United States . From January 1941 to April 1945, Hanns Ludin worked as a representative of Germany with the title “Envoy 1st Class and Plenipotentiary Minister of the Greater German Reich” to the Slovak government and resided in the “ Aryanized ” Villa Stein (a Slovak Jewish manufacturer) in Bratislava (Pressburg ).

Except for the Waagtal , a strip along the border with Moravia , the country was spared military occupation by the German Wehrmacht . Hitler only intervened directly in domestic Slovak affairs twice: on July 29, 1940, he forced a reshuffle of the government and the resignation of Foreign and Interior Minister Ďurčanský, because he operated too independently for him. The suppressed Slovak national uprising against the Tiso regime led from the late summer of 1944 to the loss of its independence and complete degradation to fulfillment of the German occupying power .

War with Hungary

2 - Southern Slovakia, as a result of the Vienna arbitration from November 2, 1938 until spring / 8. May 1945 annexed by Hungary

3 - strips of land in eastern Slovakia around the places Stakčín and Sobrance, as a result of the short Slovak-Hungarian war from April 4, 1939 to spring / 8. May 1945 annexed by Hungary

4 - Devín and Petržalka municipalities, from 1./20. Germany annexed from November 1938 to 1945

5 - German protection zone, established as a result of the protection treaty with Slovakia on March 23, 1939

The most difficult foreign policy problem was relations with its southern neighbor, Hungary, which had occupied around a third of the former Slovak territory and was trying to occupy the rest of the country as well. Slovakia, in turn, wanted to obtain a revision of the Vienna arbitration award. There were also ongoing disputes over the treatment of the Slovak population in the Hungarian areas.

On March 23, 1939, the Slovak-Hungarian War began with a raid-like invasion of Hungary into eastern Slovakia, which took place from the previously occupied Carpathian Ukraine . After an armistice and negotiations, the republic had to cede an area of 1697 km² in eastern Slovakia around the towns of Stakčín and Sobrance to Hungary.

End of the state

After the Slovak national uprising on August 29, 1944 in central Slovakia , German troops occupied the entire country from the beginning of September 1944, which ultimately lost its sovereignty completely. The German troops were under the direction of General of the Waffen-SS Gottlob Berger . After Berger, SS-Obergruppenführer Hermann Höfle became the “German commander in Slovakia” from September 1944 . He was established on September 11, 1944 as Higher SS and Police Leader in Slovakia; him under therefore were in personal union the Wehrmacht used in Slovakia, police and SS units. It was not until October 27 that Banska Bystrica fell and the last of the insurgents were arrested, deserted or defected to the partisans , who continued the resistance against the German occupation until the end of the war .

Shortly afterwards, however, the German troops were successively pushed back from the country by the Red Army and by Romanian and Czechoslovak troops from the east. A little later, the "liberated" areas became part of the restored Czechoslovakia.

On April 4, 1945, the Red Army occupied Bratislava ; from this point on, the entire Slovak territory was under Soviet control. Tiso fled to Bavaria in the Reich territory . The escape of the rest of the government did not come to an end until May 8, 1945, when they were in Kremsmünster, Austria, before XX. US Corps under General Walton Walker signed the surrender .

The Slovak Republic existed from March 1939 to July 1944, initially in "relative independence". This was followed by "from August 1944 to May 1945 [...] the complete subordination of Slovakia to the Third Reich after the occupation of the area by the Wehrmacht", until "[the] experiment of Slovak statehood [...] in the wake of the military Defeat of the German Reich no longer sustained ”.

Jozef Tiso was the first Prime Minister and State President of the First Slovak Republic to be sentenced to death and executed by a Czechoslovak court for war crimes in 1947 .

Documentation

- According to the timetable to death: Europe's railways and the Holocaust. Documentation, Germany , 2008, 52 min., Script and direction: Frank Gutermuth and Wolfgang Schoen, production: SWR ( summary of the SWR)

- Hitler's allies: Croatia, Bulgaria, Slovakia. Documentation, Germany, 2009.

See also

- History of Slovakia (360 to date)

- History of Czechoslovakia (1918 to 1993)

- Slovenské železnice (State Railway Company)

literature

- Florian Altenhöner: The foreign intelligence service of the SD and the declaration of Slovak independence on March 14, 1939. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswwissenschaft , 57 (2009), pp. 811-832.

-

Jörg K. Hoensch : Studia Slovaca. Studies on the history of the Slovaks and Slovakia . Festschrift for his 65th birthday, ed. by Hans Lemberg (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum, Volume 93). Oldenbourg, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-486-56521-4 (collected essays by Hoensch on the history of Slovakia); including:

- Jörg K. Hoensch: The Slovak Republic 1939–1945. Pp. 221-247;

- The "Protective State of Slovakia" 1939–1945. In: The development of Slovakia in the 19th and 20th centuries and its relations with the Bohemian countries up to the dissolution of the common state , p. 16 ff. (From: Czechs, Slovaks and Germans. Neighbors in Europe. Federal Center for Political Education , Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-89331-240-4 ).

- Karin Schmid: The Slovak Republic 1939–1945. A consideration of constitutional and international law. 2 volumes, Berlin-Verlag Spitz, Berlin 1982, ISBN 3-87061-238-X (= international law and politics , volume 12, diss. , Univ. Bonn, 1982).

- Lenka Šindelárová: Finale of the Extermination. Einsatzgruppe H in Slovakia in 1944/1945 . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-534-25973-1 (Diss., Univ. Stuttgart, 2012).

- Tatjana Tönsmeyer : The Third Reich and Slovakia 1939-1945. Political everyday life between cooperation and obstinacy . Schöningh, Paderborn 2003, ISBN 3-506-77532-4 (Diss., Univ. Berlin, 2002).

- Johann Kaiser: The policy of the Third Reich towards Slovakia 1939-1945. A contribution to the research of the National Socialist satellite policy. 1970 ( cf. Diss. Univ. Bochum 1969), DNB 482622628 .

Web links

- Eva Gruberová: Hitler's Shepherd. (The Catholic priest Jozef Tiso ruled Slovakia from 1939 to 1945 - and had 60,000 Jewish citizens sent to their deaths. The country's church venerates him to this day.) In: Die Zeit , No. 40/2007 of September 27, 2007

- Jana Müller: Slovakia under Tiso. A "model state" for Hitler. In: Journal of the Zeitgeschichtemuseum Ebensee , No. 46, November 1999

- The measures of the Slovak Republic against the Jews (PDF; 96 kB) - From the teaching materials of the state of Vorarlberg.

- Milan Zemko: Vojnová Slovenská republika - jasné a nedopovedané odpovede [The Slovak War Republic - clear and unanswered answers], Komentáre zo SME (komentare.sme.sk), April 8, 2013, accessed January 1, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cf. first main part of the Slovak constitution, § 1, paragraph 1: The Slovak state is a republic. and the seventh chapter, in which the citizens are divided into six classes according to their occupation.

- ^ Lacko: Slovenská republika , p. 87.

- ^ Lacko: Slovenská republika , p. 183.

- ^ For the complete analysis see Tönsmeyer: Das Third Reich , pp. 320–337; for the text see Tönsmeyer: Das Third Reich , p. 335 u. 337.

- ↑ See the law on the independent Slovak state and the treaty on the protection relationship between the German Reich and the Slovak state (Hoensch, documents , p. 258).

- ↑ Ďurica: Slovenská republika , p. 29.

- ↑ Kamenec: Slovenský štát , p. 36; Lacko: Slovenská republika , p. 35; Schönfeld: Slovakia , p. 104.

- ^ Lipták: Slovensko , p. 162.

- ^ Tönsmeyer: Das Third Reich , p. 320.

- ↑ Jörg K. Hoensch , Gerhard Ames: Documents on the autonomy policy of the Slovak People's Party Hlinkas , Oldenbourg, Munich / Vienna 1984, pp. 68–70 (section “Sovereignty instead of autonomy - the foundations of the 'Protective State of Slovakia'”, p. 69 ).

- ↑ See e.g. B. Herbert Czaja, Gottfried Zieger, Boris Meissner , Dieter Blumenwitz : Germany as a whole: legal and historical considerations. On the occasion of Herbert Czaja's 70th birthday on November 5, 1984. Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, Cologne 1985, p. 309.

- ^ Constitutional Act on the Constitution of the Slovak Republic of July 21, 1939 ; Slovenský zákonnik , 1939, No. 41, p. 375 ff., Law No. 185.

- ↑ a b c Hoensch, Studia Slovaca , p. 16 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Merkel , System Transformation. An introduction to the theory and empiricism of transformation research. 2., revised. u. exp. Ed., VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-17201-9 , p. 131 .

- ↑ Michal Broska, The Disintegration of the Czechoslovak Federal Republic , diploma thesis, p. 37 .

- ↑ Peter Heumos, The Emigration from Czechoslovakia to Western Europe and the Middle East 1938–1945 (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum; vol. 63), Oldenbourg, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-486-54561-2 , p. 18 ( Memento des Originals dated December 14, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Jörg Konrad Hoensch : Studia Slovaca. Studies on the history of the Slovaks and Slovakia. Oldenbourg, 2000, p. 199 ( Memento of the original dated November 30, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , 258 .

- ↑ Katja Happe u. a. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Volume 12: Western and Northern Europe, June 1942–1945. Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-486-71843-0 , p. 21.

- ↑ Tatjana Tönsmeyer , collaboration as a guiding motive? The Slovak elite and the Nazi regime , in: Christoph Dieckmann : Cooperation and Crimes: Forms of “Collaboration” in Eastern Europe 1939–1945 (= contributions to the history of National Socialism ; Vol. 19). Wallstein, Göttingen 2003, 2nd edition 2005, ISBN 3-89244-690-3 , pp. 25–54, here p. 52 .

- ↑ Katja Happe u. a. (Ed.): The persecution and murder of European Jews by National Socialist Germany 1933–1945. Volume 12: Western and Northern Europe, June 1942–1945. Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-486-71843-0 , p. 22.

- ↑ Milan S. Ďurica: Dejiny Slovenska a Slovákov v časovej následnosti faktov dvoch tisícročý (= history of Slovakia and the Slovaks in the chronological sequence of facts of two millennia). LÚČ, o. O. 2007, p. 795 f.

- ↑ See Hoensch, Studia Slovaca , p. 16 f. , 277 and in summary 279 f.

- ↑ Hoensch, Studia Slovaca , p. 280 .

- ↑ Members of the Slovak government had the document of surrender both before General Walton Walker and - such as B. in Hoensch (p. 246 , 304) and mentioned in another source - to be signed in front of the US Brigadier General WA Collier named there.

- ↑ Quoted from Viola Jakschová, Slovak Republic (1939–1945) , in: Alexander von Plato, Almut Leh , Christoph Thonfeld (ed.): Hitler's slaves. Biographical analyzes of forced labor in international comparison , Böhlau, Vienna 2008, ISBN 978-3-205-77753-3 , pp. 55–65 , here p. 56 .

- ↑ Quoted from Hoensch, Studia Slovaca , p. 304 .