Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia ( Czech Vysídlení Němců z Československa or Vysídlení, odsun či vyhnání Němců z Československa ) affected up to three million Germans from Czechoslovakia in 1945 and 1946.

The Sudeten Germans , also known as German Bohemians and German Moravians as well as the Sudeten Silesians , were forced to leave their homeland in 1945/1946 under threat and use of force . According to the Beneš Decree 108 of October 25, 1945, all movable and immovable property ( real estate and property rights) of the German residents was confiscated and placed under state administration.

Political usage

In English as well as in the Potsdam Agreement , the technical term transfer (German: “transfer”, “transfer”) that ignores the actual events was used, which in this context has no equivalent in Czech - the term přesun only approximates it .

The communist , partly also post-communist historiography, predominantly used the expressions “deportation” or “evacuation” (Czech odsun, vysídlení), more rarely “expulsion” (Czech vyhnání) for these processes.

Peter Glotz , in his book The expulsion of the human rights discussed issues from a German perspective. From this point of view, the terms “deportation” and “resettlement” appear as euphemisms .

Until today, the Czechs and Germans have not been able to agree on a common name for the deportations : Anyone who talks about deportation or resettlement is usually viewed by Germans as trivializing the process; in their eyes only the term “ expulsion ” seems appropriate. Czechs, on the other hand, refer to the history of the incident, which made the removal of the Germans from Czechoslovakia appropriate to many of them. They therefore chose terms other than what they considered to be unjustified or implying moral condemnation of expulsion.

However, things seem to have changed since 2015. On the 70th anniversary of the Brno death march , the local mayor used the term “expulsion” (Czech: vyhnání ) in Czech for the first time in a public declaration . This declaration was distributed in printed form to all those present at the memorial act (including the Austrian and German ambassadors to the Czech Republic).

History of eviction

19th and 20th centuries

Bohemia and Moravia had belonged to the Holy Roman Empire and then to the German Confederation until 1866 , from 1804 as part of the Austrian Empire . For some members of the Frankfurt National Assembly it was surprising in 1848 that Czech constituencies of the Austrian monarchy did not want to send members to Frankfurt because they could not imagine Bohemia and Moravia as parts of a unified Germany.

Radicals on both sides already had initial ideas or plans to radically resolve the national question in the two Austrian crown lands by expelling the Germans or the Czechs from Bohemia and Moravia. However, this position was only represented by a very small minority of both nationalities .

In the course of the growing nationalism since the 1870s, such considerations gained significantly more space in radical circles of Germans and Czechs. Many old Austrian Germans did not want to give the Czechs complete linguistic and political equality ( see: Badeni riots ). Younger Czech politicians, on the other hand, no longer wanted Bohemia and Moravia to rule from Vienna , but wanted to shape the domestic politics of the countries of the Bohemian crown just as autonomously as the Magyars, for their part, had been doing in the countries of the Hungarian crown since 1867 .

In 1871 the Bohemian Landtag decided to create an autonomous constitution ( Fundamental Article ), but this was rejected by the German Liberal Party .

Under the Austrian Prime Minister Eduard Taaffe in 1880, Czech and German became the official language again in Bohemia. However, only municipalities with a significant Czech population were administered bilingually. In 1897, the Austrian Prime Minister Count Badeni issued a language ordinance for Bohemia and Moravia , according to which all political communities there were to be administered bilingually. With this, Czech advanced to become a national language with equal rights in both crown lands . German MPs then paralyzed the Austrian Reichsrat . Due to the boycotts in parliament and in the Bohemian countries, Emperor Franz Joseph I finally had to dismiss the government, and in 1899 the nationality ordinance was watered down or repealed again.

That in turn angered the Czechs. The political blockade resulting from the rejection of full equality between the two nations in Bohemia and Moravia by the German Bohemia continued until the First World War. When Austria-Hungary disintegrated at the end of the war in 1918, the Germans of Cisleithania , who had previously used their privileges as a state-sponsoring language group , wanted to found " German Austria ", including the German-populated areas in Bohemia , Moravia and Austrian Silesia ; but the Czechs immediately occupied the Bohemian lands and prevented the Germans there from actively participating in the founding of the republican Austrian state. The German Austrians still hoped for the peace treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919; in its negotiations, however, the Czechs took part on the winning side, so that all of Bohemia, Moravia and (Austrian) Silesia were assigned to them.

As a result, the Germans were exposed to numerous forms of discrimination through laws and ordinances, even in the municipalities in which they made up the majority or even the entire population, which contributed to an increasing radicalization of the relationship between Czechs and Germans. A regulation of co-determination and self-administration rights did not succeed or was partially prevented by the Czechoslovak government. The founding of a Sudeten German movement of its own under Konrad Henlein in 1933 is one of the consequences of this failed policy.

1938-1945

The serious events from 1938 onwards, which are to be rejected under international law, with the so-called Munich Agreement , a dictation against Czechoslovakia, the occupation of so-called "rest of Czech Republic " in March 1939 , the formation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the urging of the National Socialist Germans Reichs that Slovakia should decide to adopt statehood fundamentally changed the picture.

According to consistent sources, the exile President Edvard Beneš obtained the Allies' approval for a large “population transfer” during the war; this happened in Moscow in 1943 in a personal conversation with Josef Stalin . However, the approval was kept secret.

Great Britain advised Beneš to renounce the principle of guilt. Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden warned as early as the fall of 1942 that the application of the guilt principle could "limit the extent of population displacement that might be desirable". The USA also had no objection to “the elimination of the German minority in Czechoslovakia”.

In October 1943 Edvard Beneš said in a small circle in London :

- The Germans will be repaid without pity and multiplied for everything they have committed in our countries since 1938.

In November 1944, when the country was still occupied by German troops except for Eastern Slovakia, the Czechoslovak military commander Sergěj Ingr called on the BBC :

- Beat them, kill them, don't leave anyone alive.

According to Czech sources, the anti-German mood grew gradually during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia with the opinion of the indispensability of massive forced deportation in the domestic and foreign resistance as well as in the majority of Czech society . It culminated in May 1945, so that for many Czechs further German-Czech coexistence seemed impossible.

The trigger for the mass deportation that began immediately after the end of the war was again Beneš, who now also provided the formal legal basis for the process, initially through presidential decrees and soon through parliamentary laws .

In a speech on May 12, 1945 in Brno , Beneš said that “we definitely have to resolve the German problem in the republic” (Czech. Original: německý Problem v republice musíme definitivně vylikvidovat ), and four days later on the Old Town Square in Prague that "it will be necessary, above all, uncompromisingly to eliminate the Germans in the Czech countries and the Hungarians in Slovakia" (Czech. Original: bude třeba vylikvidovat zejména nekompromisně Němce v českých zemích a Maďary na Slovensku ). Young activists in particular saw such statements as an invitation to take immediate action.

Article XIII of the Protocol of the Potsdam Conference is mostly used as a justification for the process , in which, inter alia, called:

"The three governments have advised question under all its aspects, recognize that the transfer of the German population, or elements thereof, in Poland , Czechoslovakia and Hungary were left behind, after Germany must be performed. They agree that any such conviction that will take place should be done in an orderly and humane manner. "

When the Potsdam Conference opened on July 17, 1945, the expulsion had long since begun in Czechoslovakia: by then three quarters of a million Sudeten Germans had been expelled. Since the Czechoslovaks were among the allies of the Allies, the fait accompli was "approved".

The "wild" expulsions in 1945

The first evacuation of Sudeten Germans was still due to the war: the German authorities began evacuating the Germans as the Red Army was approaching inexorably . Some Germans fled the chaos of war, but also in a disorganized way, because after the war of extermination against the Soviet Union there was fear of revenge.

With the beginning of the May uprising of the Czech people on May 5, 1945, before the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8 and thus before the liberation by Allied troops, the Czech people succeeded in gaining control in parts of the country. There the first violent measures, called “spontaneous expulsions”, took place by the Czech population against the German population who were still present.

Beneš's public speeches on May 12 and 16, in which he declared the removal of the Germans to be an absolute necessity, then formed the decisive impetus for intensifying the “wild expulsions” (Czech: divoký odsun ), which lead to brutal excesses and murderous attacks against Germans came. Between the end of the war and the practical implementation of the Potsdam communiqué (protocol), around 800,000 Germans - many of them had to go to Austria - were robbed of their homeland through these so-called wild expulsions . Due to the Beneš Decree 108, all movable and immovable property of the German residents was confiscated and placed under state administration.

In order not to have to bring the perpetrators to justice, the Provisional National Assembly passed an impunity law on May 8, 1946 for crimes committed in the "freedom struggle" between September 30, 1938 and October 28, 1945. The Beneš decree 115/46 declares actions “in the struggle to regain freedom” or those “which aimed at just retaliation for the acts of the occupiers or their accomplices” as not unlawful.

Events in the summer of 1945

- Landskron / Lanškroun , 17. – 21. May 1945: “Criminal court” on the German residents of the city with 24 murdered on the first day and a total of around 100 fatalities.

- Death march from Brno / Brno , 30.-31. May 1945: Expulsion of around 27,000 Germans. Probably around 5,200 dead, 459 of them in the Pohořelice / Pohrlitz camp , around 250 dead on the march to the Austrian border and a further 1,062 dead on the way to Vienna. Most died as a result of poor care and illness.

- Postelberg / Postoloprty and Saaz / Zatec 1947 treated by an inspection of the Czechoslovak Parliament, with large on-site approval of the population for massacre: June 15, 1945 - 31 May (as "deserved retribution" for the brutality of the Germans) collected has been; 763 bodies exhumed and cremated from mass graves in August 1947, including 5 women and 1 child; a total of around 2000 dead, murdered by the 1st Czechoslovak Division under General Oldřich Španiel. (The fewer of them left, the fewer enemies we will have) .

- Totzau / Tocov, June 5, 1945: 32 murdered. The place Tocov no longer exists.

- Podersam / Podbořany , June 7, 1945: 68 murdered.

- Komotau / Chomutov , June 9, 1945: 12 people were killed in the village. Another 70 people died on the death march. 40 people were murdered in the Sklárna camp . In addition, some people were taken from the camp by soldiers and murdered elsewhere. A total of around 140 fatalities.

- Duppau / Doupov , June 1945: 24 murdered. The city of Duppau was later demolished.

- Prerau / Moravia: On the night of June 18-19, 1945, the Prerau massacre of Zipsern refugees took place on the way back to their homeland: 265 were murdered, including 71 men, 120 women and 74 children. The oldest victim was 80 years old, the youngest victim was an 8 month old child. Seven people were able to flee.

- Jägerndorf / Krnov ; first wild expulsion on June 22, 1945. Walk from the camp on the Burgberg via Würbenthal, Gabel, Gabel-Kreuz, Thomasdorf, Freiwaldau, Weigelsdorf, Mährisch-Altstadt to Grulich. Then in an open railway wagon to Teplitz-Schönau. Then again on foot to the border to Saxony near Geising in the Ore Mountains.

- Weckelsdorf , June 30, 1945: 23 people murdered, 22 of them Germans

- Aussig / Ústí nad Labem , July 31, 1945: around 80–100 murdered; Sources name 30–700, rarely more than 2000, murdered.

- Taus / Domažlice : around 200 murdered

- Ostrau : In 1945 231 Germans were murdered in the "Hanke camp".

Beneš's promise

Edvard Beneš then promised a humane, moral approach in a speech in Mělník on October 14, 1945 , the content of which was presumably also to be registered abroad:

“Recently, however, we have been criticized in the international press for the fact that the transfer of Germans is being carried out in an unworthy, inadmissible manner. We are supposed to do what the Germans did to us; we are supposedly damaging our own national tradition and our hitherto impeccable reputation. We are supposedly simply imitating the Nazis in their cruel, uncivilized methods.

Whether these allegations are true in detail or not, I declare very categorically: Our Germans must go to the Reich and they will leave in any case. They will go away because of their own great moral guilt, their pre-war impact on us and their whole war policy against our state and our people. Those who are recognized as anti-fascists who have remained loyal to our republic can stay with us. But our entire procedure in the matter of their deportation to the Reich must be humane, tactful, correct, and morally justified. [...] All subordinate organs that sin against it will be called to order very decisively. Under no circumstances will the government allow the republic's reputation to be damaged by irresponsible elements. "

The "evacuation" from 1946

The official deportation of the German population from Czechoslovakia began in January 1946. During that year, around 2,256,000 people were resettled, mostly to Germany and a small number to Austria, where 160,000 remained. The only exceptions from deportation were people who, on the basis of the presidential decrees known as “Beneš decrees”, had been indispensable skilled workers or who were demonstrably opponents and persecuted persons of National Socialism , such as B. social democratic or communist resistance fighters .

Gottwaldschein

The so-called Gottwaldschein (named after the former President of Czechoslovakia , Klement Gottwald ) allowed parts of the German population to remain in the territory of Czechoslovakia after a phase of displacement. Since this stay on the territory of Czechoslovakia was tied to certain conditions, some who had signed this certificate decided to move to post-war Germany from 1948 onwards .

Effects

The expulsion of around three million German Bohemians and German Moravians in 1945/46 was the largest post-war population transfer in Europe after the effects of the “ Westward displacement of Poland ”, which affected five million Germans. Around 250,000 Germans were allowed to stay with limited civil rights. In 1947 and 1948, however, many of them were forcibly resettled inland. The official reason was: "Resettlement in the context of the dispersal of citizens of German nationality" (in the original: Přesun v rámci rozptylu občanů německé národnosti ).

The immediate effects of the displacement were:

- The Czech border areas were now much more sparsely populated than before, especially the rural areas. Because not enough Czech and Slovak settlers from other parts of the country were able to move in, not only did the population decline in the former Sudeten areas, but also the productivity of the traditional industries located there.

- The absence of millions of Germans, most of whom were anti-communist, made it easier for the Communists to come to power in 1948 and to incorporate Czechoslovakia into the Eastern Bloc . Through their active role in the distribution of confiscated German property, the communists were able to win additional voters and at the same time create an enemy image : the evacuated Germans, against whose revanchism and historical revisionism of Czechoslovakia only a close alliance with the Soviet Union could help.

- In the Federal Republic of Germany, and to a lesser extent in Austria, displaced Sudeten Germans were a political factor for a long time: some of the displaced or their descendants form the Sudeten German Landsmannschaft , an interest group that defines itself as a “non-partisan and non-denominational ethnic organization of the Sudeten Germans of expulsion ”(expulsion: Czech. vyhnání ).

Legal and ethical evaluation

In the 1950s, 1960s and much of the 1970s, expulsions were generally taboo from the perspective of Czechoslovakia. In the GDR and Austria, too, there was no interest in addressing the issue. Only in the Federal Republic of Germany did the associations of expellees articulate themselves in different ways, whereby a taboo was often replaced by stigmatization : Here, too, there was no legal appraisal.

It was not until 1978 that exponents of Charter 77 took the view that the disenfranchisement of Germans was the first stage in a general disenfranchisement of the entire Czechoslovak population. In the same year the Slovak historian Jan Mlynarik published under the pseudonym Danubius his "Theses on displacement", which was heavily criticized in Czechoslovakia, in which he described them as the "fruit of totalitarian dictatorships" and as "our open, circumvented and often embarrassingly interpreted problem" .

When, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, the admission of Czechoslovakia and then actually Czechoslovakia and Slovakia to the European Union began, a discussion about the international legal aspects of expulsion and the Beneš decrees started , from which the organizations of the Sudeten Germans in Germany and Austria also hoped that this would put the candidate countries under pressure.

In a legal opinion drawn up on behalf of the Bavarian State Government in 1991, the UN international law advisor Felix Ermacora expressly condemned the expulsions. In addition to Ermacora, Alfred de Zayas and Dieter Blumenwitz also represented his minority position in the assessment of the expulsion, which was particularly supported by expellees' associations and in national circles.

The majority of international lawyers, on the other hand, do not regard the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans as genocide because, as Christian Tomuschat judges, "[...] despite the seriousness of the acts, there can be no question of a targeted overall genocide campaign." The terms "genocide" and "Genocide" was used by expellee officials "as moral weapons (instead of as legal-political tools)" in order to "level out the qualitative differences between Allied / Czech and National Socialist politics".

The investigation by the experts commissioned by the EU, Jochen Frowein , Ulf Bernitz and Christopher Lord Kingsland , published on October 2, 2002, found that the Beneš decrees (affecting the German minority) did not prevent the Czech Republic from joining the EU.

Processing of the expulsion in the Czech Republic

The confrontation with violent crimes against the German population after the Second World War, which has not been carried out since the Second World War, has preoccupied the public in the Czech Republic since around the year 2000.

In August 2005, the government of the Czech Republic paid tribute to German Nazi opponents in Czechoslovakia and apologized to them for their expulsion. She announced the financing of the project "Documentation of the fate of active Nazi opponents who were affected by the measures applied in Czechoslovakia against the so-called hostile population after the Second World War". In the meantime a corresponding database has been created.

The author Radka Denemarková , born in 1968, published the novel Peníze od Hitlera (literally: Money from Hitler) in 2006 , in which she described the brutal expulsion of a Jewish survivor who had returned from a concentration camp. It was awarded the Magnesia Litera literary prize in 2007 and was then translated into several languages, German in 2009 under the title Ein Herrlicher Flecken Erde . Alena Wagnerová reviewed the work in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung : “The collective expulsion of the Sudeten Germans is still a taboo topic in World War II history in the Czech Republic . Now, with Radka Denemarková, a younger author is daring to tackle the taboo subject in a moving way. "

Former Czechoslovak and Czech President Václav Havel said in an interview in 2009 on the ethical component of displacement:

“The truth is that I criticized the eviction. I disagreed with it, not all of my life. But with an apology it's a complicated thing. [...] As if we could suddenly slip away from historical responsibility with a 'sorry'. In the end we paid more with the eviction. "

The documentary film Zabíjení po Česku (Killing in Czech) by Czech director David Vondráček, which Czech television broadcast on the occasion of the celebrations for the 55th anniversary of the liberation on May 6, 2010, at prime time, caused a sensation . Vondráček used contemporary amateur recordings of mass murders of Germans at the end of the Second World War and during the beginning of the "wild expulsions". The broadcast of the film prompted other witnesses to the massacres of Germans in Czechoslovakia to break their silence. Vondráček then produced a second documentary on the subject entitled Tell me where the dead are . Mass graves were discovered, such as in Dobronín near Jihlava . Here in May 1945 the Czechs murdered around a dozen German residents. Monuments and memorial plaques for the German victims were erected, such as in Postoloprty in Northern Bohemia in 2009 , where Czechoslovak soldiers shot about 760 Germans in May and June 1945.

On the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the expulsion, a memorial march was held in Brno on May 30, 2015 . In this context, the mayor there, Pavel Vokřál, invited the ambassadors from Germany and Austria, representatives of the associations of expellees and other politicians from both neighboring countries to use the violent expulsion of the German-speaking population from Brno as an occasion to commemorate. The Brno city council decided to sincerely regret what happened at that time.

Casualty numbers

The "German-Czechoslovakian Historians Commission", founded in 1990 by the Foreign Ministers of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Czechoslovak Federal Republic, Hans-Dietrich Genscher and Jiří Dienstbier , which has acted as the " German-Czech and German-Slovak Historians Commission" since 1993 , came in 1996 to the following result:

“The information about the victims of displacement, that is to say about the human losses that the Sudeten German population suffered during and in connection with the expulsion and forced resettlement from Czechoslovakia, diverge to an extreme degree and are therefore highly controversial. The values given in German statistical surveys range between 220,000 and 270,000 unexplained cases, which are often interpreted as deaths, the size mentioned in detailed studies available so far is between 15,000 and - at most - 30,000 deaths. "

“The difference is the result of differing views on the concept of displacement victims: detailed research tends to only consider victims of direct use of force and abnormal conditions. In contrast, statistics often include all unresolved cases among the victims of displacement. "

"The information that differs from one another also results from the fact that different collection and evaluation methods are used."

Especially when the nationalities of different groups such as individuals change, these statistics cannot be compared with one another.

Of the 18,816 documented victims of displacement and deportation, 5,596 had been murdered, 3,411 committed suicides, 6,615 died in camps, 1,481 during transports, 705 immediately after transport, 629 during an escape and for 379 deaths no clear cause of death could be assigned.

On the basis of a census, bills and estimates, and taking into account war losses, emigration and massacres, the Federal Statistical Office issued a declaration in 1958, according to which “there is a contradiction in the number of 225,600 Germans”, “whose fate has not been clarified is ". (This number has been corrected several times and is also in various sources between around 220,000 and 270,000, of which around 250,000 are said to be Sudeten Germans and 23,000 Carpathian Germans.)

Opponents of the thesis, derived from this information, that there were around 250,000 Germans who perished in the displacement, claim that it is wrong to classify these people as victims of displacement in their entirety. The number of "unsolved cases" is much higher than the number of those who can be shown to have died during the displacement and immediately after the displacement. Supporters of this version assume an actual number of victims between 19,000 (according to the total German survey , there were around 5,000 suicides and over 6,000 victims of acts of violence) and 30,000.

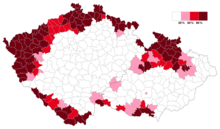

Population statistics

In 1930 there were 3,149,820 Germans in what is now the Czech Republic. According to the Czechoslovak census in 1950, 159,938 Germans lived in what is now the Czech Republic (and several thousand in Slovakia), in 1961 there were 134,143 (1.4% of the population of the Czech Republic), in 1991 48,556; In the 2001 census, 39,106 people claimed to be German. The decrease between 1961 and 1991 was probably caused by the emigration of Germans after the breakup of the Prague Spring in 1968.

Czech arguments for "resettlement"

Golo Mann pleaded for the whole of Europe “to see events and decisions between 1939 and 1947 as a single mass of misfortune, as a chain of bad actions and bad reactions”. In this sense, most of the arguments in Czechoslovakia were used to explain the “deportation”.

The opinion that still prevails in the Czech Republic today on the reasons for the expulsion of Germans from Bohemia and Moravia after the end of World War II lists the following reasons from the years 1938–1945:

- the disloyalty of a considerable part of the Sudeten Germans towards the Czechoslovak Republic founded in 1918, culminating in the demands of the Sudeten German Party under Konrad Henlein as chairman;

- the Nazis and given by him existential threat to the Czech nation (is confirmed by contemporary historical research);

- the Munich Agreement of 1938, which was imposed on Czechoslovakia and could therefore not be viewed as a treaty valid under international law ;

- the resettlement, murder and flight of the Czech population from the Sudetenland to the "rest of Czechia" (a term used by Hitler; over 150,000 people, 115,000 of them Czechs and other 70,000 to 100,000 emigrants in the second wave after the termination) following the Munich Agreement the cast);

- the 1939 occupation of the remaining Czech territory and the Nazi terror regime in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, symbolized by the Lidice massacre in 1942, with mass executions, mass expulsions and concentration camps in the Sudeten countries;

- the fact that the Sudeten Germans were declared citizens of the Reich, thus, according to the Czech view, already had the status of foreigners in 1945, and that the majority during the war mostly supported the criminal German aims of war and power;

- Sudeten Germans were often bilingual, mastered German and Czech , and from the spring of 1939 did essential work for the Nazi regime at all levels (interpreters for Nazi rulers, with the Gestapo , as judges, organizing work deportations, etc.);

- As the Czech side emphasizes, the aforementioned events and attitudes caused the general hatred of the Czech population for the Germans to grow stronger and stronger until 1945;

- the spontaneous beginning of the expulsion was a direct reaction to the extremely brutal fight against the Czech uprising in Prague , Přerov (Prerau) and other places at the beginning of May 1945.

German arguments for expulsion

- In Germany and Austria, the Nazi crimes in the Czech Republic are not denied; However, they were fundamentally opposed to collective punishments instead of examining individual cases.

- Klaus-Dietmar Henke emphasizes that from May 1945 “a storm of retaliation, revenge and hatred swept through the country”. "Wherever the troops of the Svoboda Army and the Revolutionary Guards appeared, they did not ask for guilty or innocent people, they looked for Germans." Thus, according to the German view, completely innocent people have also been expelled. The associated expropriation is viewed as fundamentally illegal.

- It is not denied that some of the Sudeten German politicians have not developed any loyalty to the Czechoslovak Republic, but it is pointed out that the right of self-determination of the Sudeten Germans in 1918/1919 to join the new state of German Austria was fundamentally ignored by the Czechoslovak politicians and the constitution of the new republic was created without the inclusion of the German ethnic group. The Czechoslovak Minister Alois Rašín said in November 1918: “The right to self-determination is a beautiful phrase. But now that the Entente has triumphed, violence decides. ”“ This is our state was the apodictic formula of the young Czechoslovak national state consciousness . […] On the other hand, there was hardly a second German minority in East Central Europe at that time who was able to develop so freely economically and to articulate so politically as the Sudeten Germans in the ČSR ”.

- It is also recalled that Sudeten German politicians were represented in the governments of Czechoslovakia from 1926 to 1938 and that the parties willing to cooperate received around 80% of the Sudeten German votes by 1935. In 1935, however, the Sudeten German Party prevailed with 68% of the Sudeten German votes.

The Federal Republic of Germany and Czechoslovakia signed the so-called Prague Treaty (or Normalization Treaty ) in 1973 and then established diplomatic relations. The Sudeten Germans criticized the fact that this treaty did not mention the expulsion and expropriation of the Sudeten Germans at all. However, the Nazi crimes in Czechoslovakia were not mentioned either; the contract does not entitle anyone to claims.

See also

literature

- Jan Šícha, Eva Habel, Peter Liebald, Gudrun Heissig (translator): Odsun. The expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. Documentation on the causes, planning and realization of an "ethnic cleansing" in the middle of Europe in 1945/46. Sudetendeutsches Archiv, Munich 1995 (accompanying volume to the exhibition, Czech edition: Odsun: Fragments of a loss, a search for traces. Illustrated by Elena-Florentine Kühn, published by the Czech Center Munich / Heimatpflegerin der Sudeten Germans, Munich 2000), ISBN 3-930626-08- X .

- Detlef Brandes : The way to expulsion 1938–1945. Plans and decisions to “transfer” Germans from Czechoslovakia and Poland. 2nd revised and expanded edition, Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-56731-4 ( Google Books ).

- Theodor Schieder (ed.): The expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia. 2 volumes, dtv, Munich 1957; unchanged reprint 2004, ISBN 3-423-34188-2 .

- Joint German-Czech Commission of Historians (ed.): Community of Conflict, Catastrophe, Détente. Sketch of a representation of German-Czech history since the 19th century. Oldenbourg, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-486-56287-8 (Czech and German).

- Tomáš Staněk : Internment and forced labor: the camp system in the Bohemian countries 1945–1948 (original title: Tábory v českých zemích 1945–1948 (= publications of the Collegium Carolinum . Volume 92). Translated by Eliška and Ralph Melville, supplemented and updated by the author, with an introduction by Andreas R. Hofmann) Oldenbourg / Collegium Carolinum , Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-486-56519-5 / ISBN 978-3-944396-29-3 .

- Tomáš Staněk: Persecution 1945: the position of the Germans in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia (outside the camps and prisons) (= book series of the Institute for the Danube Region and Central Europe . Volume 8). Translated by Otfrid Pustejovsky, edited and partially translated by Walter Reichel, Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2002, ISBN 3-205-99065-X .

- Tomáš Staněk: Poválečné excesy v českých zemích v roce 1945 a jejich vyšetřování. Ústav pro soudobé dějiny AV ČR, Prague 2005, ISBN 80-7285-062-8 . (Czech)

- Zdeněk Beneš, Václav Kural: Rozumět dějinám. Vývoj česko-německých vztahů na našem území v letech 1848–1948. Gallery pro Ministerstvo kultury ČR, Prague 2002, ISBN 80-86010-60-0 ; German version: understand history. Gallery, Praha 2002, ISBN 80-86010-66-X .

- Joachim Rogall: Germans and Czechs: History, Culture, Politics. Preface by Václav Havel. CH Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-45954-4 .

- Gilbert Gornig : International Law and Genocide. Definition, evidence, consequences using the example of the Sudeten Germans, Felix-Ermacora-Institut, Vienna 2002, ISBN 3-902272-01-5 .

- Peter Glotz : The expulsion - Bohemia as a lesson. Ullstein, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-550-07574-X .

- Wilhelm Turnwald: Documents for the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. Working group for the protection of Sudeten German interests, Munich 1951; Ascent, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7612-0199-0 .

- Emilia Hrabovec: eviction and deportation. Germans in Moravia 1945–1947 (= Vienna Eastern European Studies. Series of publications by the Austrian Institute for Eastern and South Eastern Europe). Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main / Bern / New York / Vienna 1995 and 1996, ISBN 3-631-30927-9 .

- Ray M. Douglas: Proper Transfer. The expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War. CH Beck, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-62294-6 .

- Horst W. Gömpel, Marlene Gömpel: … arrived! Expelled from the Sudetenland, taken in Northern Hesse, united in the European Union. Helmut Preußler Verlag, Nuremberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-934679-54-2 . (With many eyewitness reports, photos and documents)

- Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 .

- Renata Ripperova: View of today's society on the expulsion of Germans in the media, in information and education policy. Bachelor thesis . Masaryk University Brno, 2012 ( PDF ).

- Georg Traska (ed.): Shared memories: Czechoslovakia, National Socialism and the expulsion of the German-speaking population 1937–1948 . Mandelbaum Verlag, Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-85476-535-6 .

- Emilia Hrabovec: Expulsion and Deportation - Germans in Moravia 1945-1947 . Viennese Eastern European Studies Vol. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1995.

- RM Douglas: Proper Transfer - The Expulsion of the Germans after the Second World War . CH Beck, Munich 2012.

Web links

- Declaration of the Historical Commission of April 29, 1995 ( Memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- German-Czech and German-Slovak Commission of Historians (German-Czechoslovakian Commission of Historians)

- Czechs and Germans on the way to becoming a good neighbor ( memento of April 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ), speech by the President of the Czech Republic, Václav Havel, on the Czech-German relationship, given on February 17, 1995 in the Karolinum in Prague

- Sudeten Dialogues II: Martin D Brown and Eva Hahn (English)

- Official announcement about the Potsdam Conference from July 17 to August 2, 1945 http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/dokumente/Nachkriegsjahre_vertragPotsdamerAbkommen/index.html

- 1945: What should become of Germany? The Potsdam Conference (video)

- Piotr Pykel: The expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia. (PDF; 2.6 MB) Chapter 1. In: The Expulsion of 'German' Communities from Eastern Europe at the end of the Second World War. Steffen Prauser, Arfon Rees, 2004, pp. 11-20 , accessed on September 5, 2010 (English).

- In 1966, the West German Ministry of Refugees and Displaced Persons published statistical and graphical data illustrating German population movements, whether voluntary or enforced, in the aftermath of the Second World War. Federal German Ministry of Refugees and Displaced Persons: Statistical and graphic data illustrating German population movements (French)

- Thomas M. Buchsbaum: The “Benes Decrees” - their bilateral and multilateral aspects In: Bundesheer. 4/2003, Ed. (Austria) Federal Ministry for National Defense and Sport.

- Matthias Schmidt and Vít Polácek: Odsun - Documentation Documentation MDR, 2020

- German monasteries in Bohemia and their fate after the expulsion A contribution by the church historian Rudolf Grulich (Institute for Church History of Bohemia-Moravia-Silesia); accessed on April 14, 2021

Individual evidence

- ^ Wenzel Jaksch : Europe's way to Potsdam. Guilt and Fate in the Danube Region. Stuttgart 1958, p. 504. See Vojtech Hulík: Cesko-nemecký slovník živé mluvy s frázemi a gramatikou pro školy i soukromou potrebu / Czech-German dictionary of colloquial language with phrases and grammar for school and home , Prague 1936, p. 293 .

- ↑ Karel Kumprecht: Neubertovy slovníky "rarity" Nový Česko Německý-Slovník unique. Nakladatel A. Neubert Knihkupec, Prague 1937, p. 319.

- ↑ freunde-bruenns.com: Declaration by the City of Brno on the 70th anniversary of the expulsion of the Brno Germans in May 2015 ( Memento from July 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Declaration of May 19, 2015 on the Brno Death March of May 1945 in Wikizdroje, the Czech version of Wikisource

- ↑ Article in the magazine Týden from May 19, 2015. According to www.radio.cz/de , this magazine roughly corresponds to the Spiegel in Germany.

- ↑ Actually German- speaking MPs, but the group of people in question saw themselves as German in contrast to the numerous German-speaking Czechs at the time

- ↑ Hans Mommsen: 1897: The Badeni crisis as a turning point in German-Czech relations. In: Detlef Brandes (Ed.): Turning points in the relations between Germans, Czechs and Slovaks 1848–1989. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2007, ISBN 978-3-89861-572-3 , pp. 111-118.

- ↑ Esther Neblich: The Effects of the Baden Language Ordinance of 1897. Tectum-Verlag, Marburg 2002, ISBN 3-8288-8356-7 .

- ^ Siegfried Kogelfranz: The legacy of Yalta. The victims and those who got away. Spiegel-Buch, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1985, ISBN 3-499-33060-1 , p. 132 f.

- ↑ Klaus-Dietmar Henke : The Allies and the Expulsion. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 62.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 64.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Stoldt: Murder in the pheasant garden. In: Der Spiegel . No. 36, August 31, 2009, p. 67.

- ^ Eva Schmidt-Hartmann : The expulsion from the Czech point of view. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 147.

- ↑ SUDETENDEUTSCHE: Dangerous smoldering fire - DER SPIEGEL 8/2002. Retrieved February 20, 2021 .

- ↑ 2.3, The ethnic cleansing / expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. Retrieved February 20, 2021 .

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Expellees, Refugees and War Victims (Ed.): Documentation of the expulsion of Germans from East Central Europe: The expulsion of the German population from Czechoslovakia. 2 volumes, Bonn 1957, ISBN 3-89350-560-1 .

- ↑ Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Culture, Dept. Pres. 9 Media Service: Sudeten Germans and Czechs. Austria, Reg.No. 89905.

- ↑ Cornelia Znoy: The expulsion of the Sudeten Germans to Austria in 1945/46. Diploma thesis, Faculty of Humanities, University of Vienna, 1995.

- ^ Jörg K. Hoensch : History of the Czechoslovak Republic 1918–1978. 2nd edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1978, ISBN 3-17-004884-8 , p. 116.

- ↑ Law of May 8, 1946 ("Criminal Justification Act ") on the legality of actions connected with the struggle to regain the freedom of Czechs and Slovaks. No. 115

- ↑ heimatkreis-saaz.de

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Stoldt: Murder in the pheasant garden. In: Der Spiegel. No. 36, August 31, 2009, p. 66 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 116 f .: expulsion from Saaz.

- ^ Wilhelm Turnwald: Documents on the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. 1951, p. 472 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Turnwald: Documents on the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. 1951, p. 217 f.

- ↑ Report on the death march from Teplitz to Geising. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 111 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Turnwald: Documents on the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans. 1951, p. 119 f.

- ↑ Mečislav Borák: Internační tábor "Hanke" v Moravské Ostravě v roce 1945. [The internment "Hanke" in Moravian Ostrava in 1945]. In: Ostrava. Příspěvky k dějinám a současnosti Ostravy a Ostravska. 18 (1997), ISSN 0232-0967 , pp. 88–124 (translation into German in: Alfred Oberwandling (Ed.): It began in Mährisch Ostrau on May 1, 1945. Contemporary witness reports about the downfall of the Germans after more than seven centuries . Heimatkreis Mies-Pilsen, Dinkelsbühl 2008, ISBN 978-3-9810491-8-3 , pp. 36-66, PDF of the Go East Mission ).

- ^ Stefan Karner : War. Consequences. Research: Political, Economic and Social Transformation in the 20th Century. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2018, ISBN 9783205206743 , p. 281.

- ↑ http://docplayer.org/16426197-Die-geschichte-der-oesterreichischen-glasindustrie-nach-1945.html

- ^ Siegfried Kogelfranz: The legacy of Yalta. The victims and those who got away. Spiegel-Buch, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1985, ISBN 3-499-33060-1 , p. 132 f.

- ^ Eva Schmidt-Hartmann, in: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 149 ff.

- ↑ Samuel Salzborn (political scientist, University of Göttingen): The Beneš decrees and the EU expansion to the east - historical- political controversies between coming to terms with the past and suppressing it. (PDF)

- ^ Felix Ermacora: The Sudeten German Questions. Legal opinion. Langen-Müller Verlag, ISBN 3-7844-2412-0 , p. 235.

- ↑ WDR: Expulsion Crimes Against Humanity ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF).

- ↑ Quoted from Stefanie Mayer: “Dead injustice”? The “Beneš Decrees”. A historical-political debate in Austria. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-58270-1 , p. 120.

- ↑ European Parliament - Working Paper: Legal opinion on the Beneš-Decrees and the accession of the Czech Republic to the European Union. (PDF)

- ↑ History meeting place - extracurricular learning locations in the Bavarian-Bohemian border region , a project of the University of Passau and the South Bohemian University in Budweis

- ^ From the Czech by Eva Profousová. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Munich 2009; English Money from Hitler , also Polish and Hungarian.

- ^ Alena Wagnerová: The carousel of enmity , book reviews about Radka Denemarková, In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . No. 281, December 3, 2009, p. 50.

- ↑ Der Standard , Vienna, May 7, 2009, p. 3; Interview by Michael Kerbler and Alexandra Föderl-Schmid in Prague 20 years after 1989.

- ↑ "" Killing the Czech Way "- a controversial film about mass murders after May 8, 1945" . Info from Radio Praha , May 6, 2010

- ↑ "Zabíjení po česku" , Video, Česká televise

- ↑ See also «Zabíjení po česku» - «Killing in Czech». The "wild expulsion" of 1945 from today's perspective . Abstract of a master's thesis at infoclio.ch

- ↑ “Tell me where the dead are” - new documentary about the massacre of German civilians . Info from Radio Praha , April 29, 2011

- ^ Letter from the politician to the chairman of the Sudeten German Landsmannschaft in Austria dated March 31, 2015.

- ↑ Brno regrets death march. In: Kurier , Vienna, May 21, 2015, p. 7 ( kurier.at ).

- ^ Opinion of the German-Czech historians' commission on the expulsion losses. Prague – Munich, December 18, 1996. Printed in: Jörg K. Hoensch, Hans Lemberg (Ed.): Encounter and Conflict. Highlights from the relationship between Czechs, Slovaks and Germans 1815–1989. Essen 2001, pp. 245–247.

- ^ Golo Mann: German history of the 19th and 20th centuries , 18th edition of the special edition, S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1958, ISBN 3-10-347901-8 , p. 969.

- ^ Leopold Grünwald (ed.): Sudetendeutsche - victims and perpetrators. Violations of the right to self-determination and their consequences 1918–1982. Junius, Vienna 1983, ISBN 3-900370-05-2 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 65.

- ^ Alfred Payrleiter: Austrians and Czechs. Old strife and new hope. Böhlau-Verlag, Vienna 1990/2003, ISBN 3-205-77041-2 , p. 156.

- ^ Rudolf Jaworski: The Sudeten Germans as a minority in Czechoslovakia 1918-1938. In: Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 30.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): The expulsion of the Germans from the East: causes, events, consequences. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24329-7 , p. 32.

- ^ Treaty of December 11, 1973

- ↑ See also the preparatory work by Fritz Valjavec since 1951, whose inclusion in the Theodor Oberländer series was successful.

- ↑ Michael Schwartz : A taboo dissolves. Review. In: The time . No. 24 of June 20, 2012.