Frankfurt National Assembly

The Frankfurt National Assembly (also Contemporary constituierende national assembly , German National Parliament , the Imperial Parliament , Frankfurt parliament , already Reichstag ) was from May 1848 to May 1849, the constitutional committee of the German Revolution and the preliminary Parliament of the emerging German Empire . The National Assembly met in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt , therefore the name Paulskirche often stands for the National Assembly. As a parliament, the National Assembly also passed the imperial laws . On 28 June 1848, the National Assembly established with the central power law , the Provisional Central Power one, so a provisional German government.

The Bundestag of the German Confederation passed a federal electoral law at the end of March and beginning of April 1848 so that the German people could elect a national assembly. The election was organized by the individual German states. The National Assembly was supposed to draft a constitution for a German federal state that was to be agreed with the individual states . Out of its own awareness of power, however, it also put itself and a central authority in place of the organs of the German Confederation.

On March 28, 1849, the National Assembly passed the Frankfurt Constitution (Constitution of the German Empire). In their view, it was the only one capable of enforcement. The constitution was adopted by most of the individual German states and both chambers of the Prussian state parliament , but not by the Prussian king and the large individual states such as Bavaria and Hanover . Austria had de facto excluded itself from the new German Empire through a new constitution imposed by the emperor for a unified Austrian state.

In May Prussia and Austria, and then other states as well, ordered the members of parliament from their countries to resign their mandate and now opposed the revolution with open violence. The Reich constitution campaign failed. Other resignations also reduced the number of MPs until the National Assembly was dominated by the left. At the end of May 1849, the remaining MPs fled to Stuttgart and formed a rump parliament there , which, however, remained meaningless and was dissolved by the Württemberg military on June 18.

The former members of the constitutional liberals, the right-wing center, met at the end of June in the Gotha post-parliament , a private assembly. There they essentially accepted the Prussian attempt to establish the Erfurt Union as a small German state. While many left-wing MPs left Germany or were persecuted, there were a larger number of MPs who later belonged to the Reichstag of the North German Confederation and the German Empire . The most prominent was Eduard von Simson , President of the National Assembly, the Erfurt Union Parliament and first President of the Reichstag.

history

Election of the National Assembly

At the beginning of the German Revolution , in March 1848, the Bundestag was initially the focus of the all-German renewals. The Bundestag was the highest organ of the German Confederation, with envoys from the individual states. In addition, a pre-parliament was formed , an assembly of members of the parliaments of the individual states.

One of the most important decisions of the time was the Federal Election Act , more precisely two Bundestag resolutions of March 30th and April 7th on the proposal of the preliminary parliament. According to the federal electoral law, the individual states should have members elected to a constituent German national assembly. The federal electoral law gave them a basic framework for this, for example that for every 50,000 inhabitants one member had to be elected and that every male, adult, self-employed citizen could vote. In the absence of a provision, states could decide for themselves whether the election should be direct or indirect.

Although the National Assembly was supposed to meet on May 1st, elections were held in some states on that day or later, and it took a few days before the results were determined. The legal and factual conditions of the election were very different from region to region; overall, it is assumed that the voter turnout was between forty and seventy percent.

Final phase

The rejection of the imperial crown by Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia caused great consternation in the National Assembly. However, it adhered to the imperial constitution and elected a committee of thirty to examine the report of the emperor's deputation . The aim was to subdue the princes and governments through public opinion. A note from the twenty-eight , the plenipotentiary of smaller states, adopted the constitution, as did the Chamber of Deputies of the Prussian National Assembly . The latter threatened their king with further refusal that they would no longer support the Prussian government.

The conflict then escalated: at the end of April the king not only finally rejected the imperial crown, but also dissolved the Chamber in Prussia; the same happened in Hanover, Saxony and other states. On May 3, the National Assembly set a deadline for recognition and decided with 190 to 188 votes on May 4 that it itself announced the elections for the first Reichstag instead of the emperor (the Prussian king). This should elect a new emperor. She called on governments, parliaments, municipalities and the people in general to enforce the constitution. When the left called for acts of violence, the moderate MPs gradually resigned.

Like the Austrian government before, the Prussian government announced on May 14th that the mandates of the Frankfurt deputies from Prussia had expired and that these deputies were no longer allowed to attend the meetings. With the failure of the constitutional agreement, the task of the National Assembly was done. The Prussian government no longer saw the National Assembly as the legal representative of the people. Saxony and Hanover followed the Prussian example in May, Baden in June 1849. The coup-like measure was unlawful because the elections to the National Assembly were based on state election laws that were still in force, and the state election laws in turn were enforcement measures of the federal election law, which was also still in force was.

Many MPs submitted and resigned, the last more prominent in the political center on May 26, when the majority called on the people to violence. On May 30, 71 to 64 MPs decided, with four abstentions, to move the seat to Stuttgart because they feared the invasion of Prussian troops in Frankfurt. The rump parliament of around one hundred in Stuttgart was initially tolerated by the Württemberg government, but was dissolved by force of arms on June 18. Most of the MPs fled to Switzerland. The Greater German Conservatives (together with the Central Authority) remained in Frankfurt, they saw themselves as the legitimate National Assembly.

Functions

The Frankfurt National Assembly initially had only one clear task: According to the federal electoral law, it should draft a constitution for all of Germany and agree this with the governments. However, when the National Assembly took office, the question of the continued existence of the Bundestag and the establishment of a federal executive arose. The war against Denmark and other problems indicated a need for action. So the National Assembly also made decisions outside of its original task, it served as a parliament for imperial legislation and worked together with the central authority it had appointed.

Central power

After lengthy deliberations on a federal executive, i.e. a government for the federal or Reich level, the National Assembly passed the Reich Law on June 28, 1848 on the introduction of a provisional central authority for Germany . The provisional constitutional order for Germany provided for an imperial administrator , a kind of substitute monarch, who appointed ministers. The National Assembly defined the following role for itself in the Central Power Act:

- She chose the imperial administrator

- The ministers were responsible to her, the entire Reich Ministry

- The ministers had to give her information on request

- Together with the central authority, it decided on war and peace and treaties with foreign powers

On June 29th, the National Assembly elected Archduke Johann of Austria as Reich Administrator. He appointed the Leiningen cabinet in July and August and later also other cabinets. Although it was not expressly regulated that a minister had to resign at the request of the National Assembly, this was de facto the case, also because the National Assembly was the most important political support for the government. So a parliamentary way of government prevailed. The National Assembly, however, did not have the opportunity to remove the Reichsverweser Johann, even if the Stuttgart rump parliament later declared its activity to be illegal.

Reich legislation

The results of parliamentary work include a number of laws and ordinances on various subject areas. Some of them deal directly with the activity or the status of the members of parliament, such as the Reichsgesetz, concerning the procedure in the case of judicial indictments against members of the constituent Reich Assembly of September 30th, 1848. Others relate to the central authority, while others, not least, had the purpose of to demonstrate the usefulness of the National Assembly as a legislature that creates order and unity by means of rather undisputed regulations, especially the General German Exchange Ordinance of November 24, 1848.

The members of parliament considered the fundamental rights of the German people to be particularly important ; they were actually part of the future constitution, but were passed as a Reich law on December 20, 1848. The catalog of basic rights stipulated individual civil liberties for Germans, but also, for example, institutional guarantees with regard to the administration of justice, and it prohibited punishments such as pillory and, to a large extent, the death penalty . Because of the abolition of noble privileges, the catalog of basic rights was naturally not welcomed by absolutely all Germans.

Laws were passed by the National Assembly and then signed by the Reich Administrator and the relevant Minister, in order to be published in the Reichsgesetzblatt . The basis for this procedure was the imperial law on the promulgation of imperial laws and the decrees of the provisional central authority of September 27, 1848. No law, but a comparable earlier resolution of the National Assembly of June 14, 1848 led to the creation of a German imperial fleet .

A publication of the imperial laws in the corresponding legal gazettes of the individual states was not necessary for the validity of the imperial laws. Similar to the central power and the imperial constitution, it was again the small states that recognized the imperial legislation in principle, while the medium-sized states and major powers blocked themselves. Despite the Federal Reaction Resolution of 1851, which fought against the Reich legislation and its consequences in state legislation, the legal legacy of the National Assembly lived on and was partially incorporated into the legislation of the North German Confederation .

Constitution

Especially after the difficulties in the summer and autumn of 1848 in gaining recognition for the emerging German Reich and its central authority, the members of parliament concentrated on constitutional work. In doing so, they had to take into account the political situation in Germany, above all the dualism of Austria and Prussia, as well as considerable differences of opinion that also existed within the National Assembly. The territory and the head of the Reich were particularly controversial .

At the beginning, the MPs assumed with the utmost of course that the previous federal territory should essentially become the Reich territory and that the corresponding part of Austria belonged to it. However, Austria made it abundantly clear in early March 1849 at the latest that it only wanted to be part of a German state organization with all its territories (including Hungary and Northern Italy) and that it rejected a national parliament. Germany was supposed to be a federation of states across Austria . Prussia, on the other hand, sent cautiously positive signals about German unification. This situation meant that the constitution lists the members of the Reich including Austria, but speaks of the possibility that Austria will only join the Reich later. Similarly, Schleswig's membership of the Reich was reserved for a later regulation.

The majority of the MPs supported a single person as head of the Reich, namely a monarch. The Republicans were generally in the minority, but for a long time there was still the idea of placing a multi-headed body at the head of the empire. Votes in March 1849 then led to the decision that the National Assembly should elect one of the German princes as emperor, whose crown should then be hereditary (hereditary imperial solution). The National Assembly also elected the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. As emperor at the end of March .

Linked to this was the question of the emperor's power, which was also only decided in March. The right and the center right advocated an absolute veto by the emperor, which means that laws of the Reichstag could only come into force with his consent. The left-wing MPs wanted a suspensive veto: the emperor's objection would only have postponed the entry into force of a law. The latter view prevailed through voting agreements because some left votes were needed for the solution without Austria ( Simon-Gagern Pact ).

Contrary to the intent of the Federal Electoral Act of 1848, the MPs promulgated the constitution on their own initiative, without agreement with the governments of the individual states. According to the Central Authority Act, the constitution was not a task for the central authority. The constitution came into force when it was promulgated on March 28, 1849, and was signed by the President of the National Assembly, Eduard Simson, and the other members of parliament. Today's specialist literature disagrees about the validity; some authors affirm it, others deny it, others say mediating, for example, that it has not become legally effective.

Ultimately it was a political decision at the time whether to recognize them or not. As a result, 28 governments , under pressure from the King of Württemberg and also the revolutionary regimes in Saxony and the Palatinate, recognized the constitution. The fickle King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, however, rejected it, as did the imperial crown (finally on April 28), and together with other monarchs put down the revolution.

The Frankfurt Reich Election Act of April 12, 1849 is in itself a simple Reich law, although materially it belongs to the Reichstag and thus to an organ of the Reich constitution. For practical reasons, too, the Constitutional Committee has moved the issue out of the constitution. The committee itself had initially proposed an unequal electoral law that would have excluded many voters in the National Assembly from voting again. Also because the small German hereditary imperial party needed the votes of the left-wing MPs, the same and universal male suffrage prevailed for the Reich election law. More precisely, the law regulated the elections to the People's House of the Reichstag, but this election was no longer held because of the suppression of the revolution.

MPs

Number and regional origin

According to the federal register , with its outdated population figures, and the formula that one member had to be elected for every 50,000 inhabitants, the number is 649. However, some constituencies in Bohemia and Moravia with Czech populations boycotted the election. Therefore, only the 33 members of the German mother tongue from Bohemia, Moravia and Austrian Silesia were represented in the National Assembly. So you get 585. Since many members of parliament, for example, held a state parliament mandate or government office, there were usually around 400 to 450 members in Frankfurt. Up to 540 MPs cast their votes on important votes. In April 1849 there were 436 before the Austrians were recalled.

Figures on the total number of MPs at all times differ, according to Jörg-Detlef Kühne , a total of 799 MPs had appeared. This was due to the fact that around a quarter of the MPs were replaced, mostly by substitutes, to a lesser extent by by -elections . Siemann names a total of 812 MPs, Nipperdey 830, Jansen comes to 809 after preliminary work by other authors. This number is also used in the Biographical Handbook by Heinrich Best and Wilhelm Weege: Your criterion is participation in at least one session of the National Assembly or the rump parliament as far as it was documented by the official protocol. However, the protocol was poorly kept at the beginning and in the dissolution phase.

All MPs were divided into one of 15 departments by lot. For the election test, each department checked the legitimation of the members of another. An election contestation had to be registered within the first two weeks of the National Assembly (or after a new election). The election could only be contested if the objected points could have an influence on the result. The chairmen of all 15 departments formed the central electoral committee, which, if necessary, referred cases to the plenary session of the National Assembly.

| Country | Constituencies | MPs |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 132 | 186 |

| Prussia | 200 | 280 |

| Bavaria | 71 | 91 |

| Hanover / Oldenburg | 31 | 41 |

| Württemberg | 30th | 42 |

| Saxony (Kgr.) | 24 | 36 |

| Thuringian states | 14th | 23 |

| to bathe | 19th | 21st |

| Hessian states | 32 | 36 |

| Hanseatic cities | 3 | 7th |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | 7th | 9 |

| Holstein / Lauenburg | 7th | 8th |

| Schleswig | 5 | 6th |

| Braunschweig | 4th | 5 |

| Anhaltinian states | 3 | 5 |

| Limburg | 2 | 2 |

| Luxembourg | 1 | 4th |

| lip | 1 | 1 |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | 1 | 1 |

| Liechtenstein | 1 | 1 |

Well-known MPs

Among the benevolent contemporaries one can find descriptions according to which the National Assembly united “the best minds of the time” or the “intellectual elite of Germany”, and they no longer had their kind. Many MPs were already known to the entire German public, including two very old pioneers of the national movement such as Ernst Moritz Arndt and the “gymnastics father” Friedrich Ludwig Jahn . Like the writer Ludwig Uhland , however, they were hardly involved in parliamentary work with their parliamentary groups.

Important scholars in the humanities, especially in the “Germanic” subjects, were the linguist Jacob Grimm and the historians Georg Waitz , Johann Gustav Droysen and Georg Gottfried Gervinus , as well as the legal scholars Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht , Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann and Robert von Mohl . Actual politicians with national fame were already Heinrich von Gagern , Robert Blum , Ludwig Simon and Johann Adam von Itzstein .

Social composition

Veit Valentin , like other historians, complained that the "lower class of the population was completely inadequately represented". No workers, only a single farmer and only four master craftsmen as representatives of the middle class would have sat in the Paulskirche. “The Frankfurt Parliament was too much of a university and too little of a political stock exchange. It was not a true reflection of the social stratification in Germany at that time [...]. The Frankfurt parliament was a kind of elected upper house. "

In contrast, Thomas Nipperdey calls it "silly to expect a parliament to reflect the social structure of the electorate". The National Assembly was a parliament of dignitaries , but not through manipulation, because the social hierarchy prevailed at the time, especially with general, democratic suffrage. Furthermore, one must not equate the political orientations and the social status of the voters: there was a lot of overlap, the democrats were not just the common people and the liberals were not all notables or "bourgeoisie".

Just like Nipperdey, Hans-Ulrich Wehler rejects the widely used word “professors' parliament ”, although some professors were actually very well known. This job title was only valid for 12 percent of the MPs, of which half (49 MPs) were professors at universities and the rest at higher schools. Much more appropriate would be a designation as "civil servants 'parliament" (around 56 percent) or as "jurists' parliament" (around 50 percent). Wehler:

“The educated bourgeois dignitaries had the undeniable preponderance, but apparently also the confidence of an electorate that was politically mobilized for the first time. The services of the Paulskirche are due to this majority; conversely, they are largely responsible for the political mistakes. Praise and criticism are plentiful. There was only one thing these active educated citizens were certainly not: apolitical exponents of aristocratic inwardness! "

The academically educated provided a share of at least 81.7 percent, which was significantly higher than at the constituent Reichstag of 1867 (62.6 percent), at the Weimar National Assembly (just under 38 percent) and at the Parliamentary Council (66.2 percent) . The academic professions are broken down into (in percent of all MPs): Justice and administration 47.5 percent; Apprenticeships 15.8 percent; Liberal professions 6.9 percent; Marginalized intelligence 6.4 percent; Clergy 4.7 percent. In addition, 8.4 percent of the MPs belonged to the bourgeoisie, 6.6 percent to the landlords and 2.4 percent to the officers. Ten MPs (1.2 percent) belong to the lower middle class.

With an average of 43.5 years, the Frankfurt MPs were significantly younger than, for example, the members of the Parliamentary Council (54.1 years, first Bundestag: 50 years, comparable to 1867 and 1919). This is partly due to the increased general life expectancy, and the members of the Swiss Federal Assembly in 1848 had a similarly low average age. Younger MPs were more likely to join the left, older members of the right. A vote for a left was a vote against the regional elites, while the areas little affected by the revolution voted primarily the “old fighters of the pre-March opposition”.

43.1 percent of the MPs had Catholicism as a religious creed, with a Catholic population in the German Confederation of 54.2 percent. This denomination was clearly underrepresented. This has to do with the fact that the political elites were more likely to be Protestants: With a population of 46.8 percent, Protestants made up 54.6 percent of the MPs. Jews, one percent of the population, were seven MPs (0.9 percent). In addition, there are 11 MPs (1.4 percent) of the MPs who belonged to the German Catholic or free religious denomination (they do not appear in the population statistics).

The Frankfurt MPs had rather little experience in state, provincial or municipal assemblies, according to a rough estimate about a fifth. The value increases if one adds the (short) activity in the Fifties Committee and in the pre-parliament. The proportion is also higher among the south-west Germans with the parliamentary tradition there. A Prussian from the Rhineland asserted in the first session, without being contradicted, that a large number had already sat in chambers, which may have had something to do with the United State Parliaments or the elected municipal councils in Prussia. Kühne estimates that the proportion in 1848/1849 was the same as in 1867 (namely 36.7 percent). The limited parliamentary experience may have had negative consequences for the functioning of the National Assembly and the quality of its results. However, according to Kühne, it cannot be read from the content of the imperial constitution that the members of parliament were not realistic.

Later parliamentary activity and persecution

The Erfurt Union Parliament was elected at the end of 1849 and beginning of 1850 ; of its members, twenty percent have already sat in the Frankfurt National Assembly. This applies to 59 MPs in the Volkshaus (out of a total of 224) and three in the State House (out of 96). If one also takes into account members of the pre-parliament, there are six members in the Volkshaus and ten members in the State House.

51 of the Frankfurt MPs sat in the North German Reichstag from 1867 and in the German Reichstag from 1871. In the two North German Reichstag of 1867 each 5.6 percent of all members belonged to this group, in the first German Reichstag of 1871 it was 7.7 percent. The proportion then fell significantly. Nine other Frankfurt deputies were South German members in the customs parliament of 1868. The last two deputies of the Frankfurt National Assembly in the Reichstag were Karl Mayer and Hermann Henrich Meier , who were elected in 1884. Eduard Simson, Georg Beseler and Robert Mohl were among the most famous members of the Reichstag from the Frankfurt period.

There is evidence that 136 of the left-wing MPs were prosecuted under criminal or service law; some escaped the latter by giving up their office, for example Carl Friedrich Rheinwald , who resigned from his professorship. 18 MPs were sentenced to death, two of which actually resulted in execution (Robert Blum, Wilhelm Adolph von Trützschler ). The others fled and their assets were usually confiscated, as well as long-term imprisonment. Two others were sentenced to death and pardoned for life ( Otto Leonhard Heubner , dismissed in 1859). Otherwise, the penalties ranged from symbolic fines ( Ludwig Uhland , Friedrich Theodor Vischer ) or non-recognition of the election as mayor, the revocation of the title chamberlain ( Otto von Waxdorf ), suspension ( Carl Alexander Spatz 1853, because of contact with exiles), and banishment Austria ( Heinrich Reitter ). Ludwig Simon from Trier was sentenced to death in absentia and later called up for a reserve exercise in order to be able to convict him for desertion in addition to a heavy fine and imprisonment.

Twelve members of parliament were not persecuted for participating in the rump parliament, others sentenced to death (for high treason ). In protest, Uhland refused to be accepted into the order Pour le mérite . Even after proceedings were discontinued or sentences had been served, those persecuted were monitored by the police, including their relatives and acquaintances. The latter damaged the reputation of many citizens who were not politically active themselves. Many former MPs withdrew from politics because they feared stalking, Jansen emphasizes, not because they had become “Philistines”.

Like Blum, two other MPs died violently during the National Assembly: Hans von Auerwald and Felix von Lichnowsky . During the September riots in Frankfurt, the two members of the casino found themselves in an angry crowd protesting against the armistice decision of the National Assembly.

Working method and internal organization

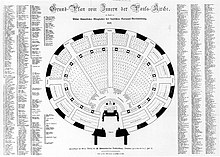

Paulskirche conference location

The Evangelical Community of Frankfurt made the Paulskirche available to the National Assembly . Instead of the altar, the lectern for the presidium and the speaker was placed, the church organ above it was covered with the painting Germania , on both sides of which in the gallery was the library of the German Imperial Assembly . Otherwise, the gallery was the place from which visitors followed the negotiations of the National Assembly.

Disadvantages of the Paulskirche were the narrow corridors between the rows of seats in the crowded plenary hall and the lack of offices or rooms for consultation. The gallery gave space for two thousand spectators, who audibly interfered in the debates, but the members of parliament also gave loud applause or reprimand in the feverish atmosphere.

Rules of Procedure

The Committee of Fifties , which emerged from the pre-parliament , could theoretically have drafted rules of procedure for the National Assembly, but rejected this on April 29, 1848. Even before the meeting, Robert Mohl was working on a draft which he worked out together with two other members after a meeting of MPs who had already arrived in Frankfurt. The draft was completed on May 10th and adopted as provisional regulations at the first meeting on May 18th. A commission was set up for this purpose, which drew up the definitive rules of procedure of May 29, which were adopted after a brief discussion. The six 49-paragraph sections covered: Elective Exam; Board of Directors and the staff of the Assembly; Publicity and quorum; Committees; Order of debate; Inputs.

The rules of procedure stipulated, among other things, that the meetings were public, but could be confidential under certain conditions; The National Assembly had a quorum when two hundred members were present. The items to be negotiated were discussed in advance in the 15 departments. It was regulated how motions were dealt with (twenty supports were required to present them in plenary) and the agenda was set by the President at the end of the previous session. Speakers spoke in the order in which they presented themselves, but with a variety of opponents and supporters of the proposal. Speaking time was not limited. Twenty MPs together could request the end of a debate, the decision then rests with the plenary. It was not specifically stipulated that the MPs were free to choose their seat.

The rules of procedure were modified through formal change or simple use. The preliminary consultation in the departments was overlaid by the parliamentary groups, so that the planned new draw was dispensed with. The political groups largely determined the speakers in a debate. Speaking time was not limited despite two requests. A roll-call vote with a call by name had to take place if at least fifty MPs requested it; Bassermann only wanted to allow this if necessary due to uncertainty about the voting result, but the opponents saw the roll-call vote as the point of documenting to the voters who had voted and how. Finally, to save time, voting cards were introduced on October 17, 1848 (white “yes”, blue “no”). Who had voted how, was then later in the minutes. An anonymous voting process was generally rejected.

Full board

On May 17, more than three hundred MPs met in the Frankfurt Römer ; they decided that the National Assembly should be opened by an elderly president, not the board of the Fifties Committee, as Robert Mohl had suggested. The next day they met again in the Römer, appointed the seventy-year-old Friedrich Lang as old-age president (although he was not the oldest of all members of parliament) and the eight youngest present as “old-age secretaries”. Then the 350 or so members moved together to the Paulskirche. The first session was chaotic and haphazard, and when Heinrich von Gagern was elected President on May 19, some MPs only wrote “Gagern” on the ballot, although there was another MP of that name with his brother Maximilian gave. Heinrich von Gagern quickly cleared up the chaos of the beginning.

According to the Rules of Procedure of May 29, an absolute majority of the MPs present elected the President and the two Vice-Presidents of the National Assembly. They had to be re-elected every four weeks; that was an innovation that went back to Mohl and was supposed to keep the office of president open to everyone. The president kept the house in order, set the agenda, and presided over the meeting. The entire board also included eight secretaries who were jointly elected by a relative majority for the entire duration.

The full board appointed the assembly staff, the office. In November 1848 these were a board of directors of the office, a registrar with eleven assistants and eight secretarial assistants. The stenographic office had a board of directors (MP Wigard ), under which twelve stenographers and 13 registrars worked. The staff also consisted of messengers and servants.

The presidents were:

- Friedrich Lang as senior president, May 18, 1848 to May 19, 1848

- Heinrich von Gagern , May 19, 1848 to December 16, 1848

- Eduard Simson , December 18, 1848 to May 11, 1849

- Theodor Reh , May 12, 1849 to May 30, 1849

Friedrich Wilhelm Löwe was President of the Stuttgart Rump Parliament from June 6, 1849 to June 18, 1849.

Factions

- Democrats : 15

- Left liberals : 13

- Non-attached: 32

- Right-wing liberals : 34

- Conservatives : 6

- Democrats : 121

- Left liberals : 104

- Non-attached: 258

- Right-wing liberals : 274

- Conservatives : 48

From the point of view of the MPs, working in political groups was a necessary evil. Since June they have helped to determine the course of business, limit the number of random decisions, form coalitions and influence the public with their own publications. They work with political associations outside parliament and reflect society with its various elements. A democratic-pluralist party system was to be foreseen as a further consequence.

Fractions were named after the restaurant where the MPs met. In October 1848 these were (in brackets the approximate strength of the parliamentary group in percent):

- Conservative rights: Café Milani (6)

- Constitutional-liberal right-wing center: Casino (21), Landsberg (6) and Augsburger Hof (7)

- Parliamentary-liberal left center: Württemberger Hof (6), Westendhall (7)

- Democratic left: Deutscher Hof (8), Donnersberg (7)

About a third of the MPs did not belong to any political group.

From October onwards, the question of Kleindeutsch / Großdeutsch was superimposed on the otherwise stable factions; in February 1849 the groups on this question were called:

- The Greater Germans met as " Mainlust ". It was about the left with about 160 members who advocated a unified state, and also about a spin-off of the casino called Pariser Hof , about a hundred southern Germans and Austrians, often Catholic and federalist. However, the Parisian court and the left were very divided on other issues.

- The small German or hereditary imperial party was the " Weidenbusch " with about 220 members. It was rather north German Protestants who came from the Casino, the Landsberg, the Augsburger Hof and partly the Württemberger Hof and occasionally the Westendhall.

- The " Braunfels " consisted of liberals and democrats, especially from Westendhall. They offered the Weidenbusch a compromise if this would strengthen the imperial constitution through democratic elements such as universal suffrage.

In the important constitutional votes in March 1849, the three groups did not vote uniformly, but on the question of whether the imperial dignity should be hereditary, thanks to the Simon Gagern Pact (from Braunfels and Weidenbusch), 267 members voted yes and 263 No.

Committees

In total, the National Assembly has set up 17 independent and ten temporary committees. A member of parliament had to belong to at least one. If a seat became available, the committee proposed three MEPs, one of whom the plenary elected. The meetings were not open to the public, but the President was allowed to attend them all. Contrary to the original regulation, a committee could question witnesses and experts without the express consent of the plenary.

List of committees:

- Preparatory Commission for the Establishment of the National Assembly, May 18, 1848 to June 17, 1848

- Revision commission for preliminary consultation on the contracts concluded by the preparatory commission, May 19, 1848 to June 16, 1848

- Standing Orders Committee, since May 19, 1848

- Drafting committee for the minutes, May 22, 1848 to June 16, 1848

- Committee on Raveaux's motion, since May 22, 1848

- Central Committee for the Examination of Elections, since May 23, 1848

- Committee for the draft of the Imperial Constitution ( Constitutional Committee ), since May 24, 1848

- Committee on Labor, Industry and Trade Relations (Economic Committee), since May 24, 1848

- Committee on the Priority of Petitions and Motions, since May 24, 1848

- Committee on the Navy, since May 26, 1848

- Committee on International Law and Questions, since May 29, 1848

- Committee for Examination of Motions Relating to the Provisional Central Authority, since June 3, 1848

- Committee on People's Armament and Army, since June 5, 1848

- Committee for the Assessment of the Austro-Slavic Question, since June 5, 1848

- Legislative Committee, since June 17, 1848

- Committee for the review of the elections in Thiengen and Konstanz, since July 1, 1848

- Committee on Drafting the Law on Ministerial Responsibility, since July 1, 1848

- Committee for Church and School Affairs (Commission for Education and Public Education), since July 7, 1848

- Committee for Section for Elementary Schools

- Commission for preparing the reception of the Reich Administrator, since July 10, 1848

- Finance Committee, since August 25, 1848

- Committee on drafting a proclamation for the National Assembly, since September 20, 1848 (relating to the September riots)

- Committee on Schmidt-Wiesner's motion, since October 5, 1848

- Committee for the initiation of the investigation against the deputies Robert Blum and Johann Georg Günther, since October 5, 1848

- Committee for Austrian Affairs, since October 17, 1848

- Committee for Motions on the Relationship of Central Power to the Individual States, since November 7, 1848

- Commission for the orders for the funeral ceremony for the representative Robert Blum, since November 23, 1848

- Committee to assess and report on the submission by the Reich Ministry on Austria's relationship to the formation of a federal state of the German states, since December 18, 1848

- Committee for the Implementation of the Imperial Constitution (Thirties Committee), since April 11, 1849

- Committee of Fifteen, since June 8, 1849

rating

The National Assembly and other assemblies of the time “showed many approaches to a developed parliamentarianism,” said Siemann. The way of government was parliamentary, political groups formed the will and effective committee work overcame influences from outside the National Assembly. In dealing with political power in democratic institutions, the bourgeoisie was astonishingly mature and capable of parliamentary compromises, crowned by basic rights and “the balanced construction of the imperial constitution”.

Hahn and Berding recall the numerous demands of a politicized society, which were brought to the parliamentarians, through associations, newspapers, interest groups and petitions. "The interplay between representative representation of the people and an initially unrestricted public, as made possible by the revolution, made the Paulskirche the political forum of the nation."

In spite of its remarkable achievements in the constitution and legislation, Frank Lorenz Müller believes, the National Assembly did not grow into a “hands-on, practical body”; it remained too technical and philosophical. Bernhard Mann accuses her of having overstimulated her trump cards in May and June 1848, and that her position of establishing the constitution without the governments was untenable. In addition, it should have set up a central authority that was completely dependent on it in order to achieve more parliamentarization and party formation across the country. But one must justly add that a modern party system had only just become possible through the freedom of the press, assembly and association, and that the Austrian politicians had little and the Prussian at least little experience in parliamentarianism.

See also

literature

- Heinrich Best , Wilhelm Weege: Biographical manual of the members of the Frankfurt National Assembly 1848/49. Droste, Düsseldorf 1998, ISBN 3-7700-0919-3 .

- Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977.

- Günter Mick: The Paulskirche. Arguing for law and justice. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1997, ISBN 3-7829-0470-2

- Karl Obermann : The elections to the Frankfurt National Assembly in the spring of 1848. The election processes in the states of the German Confederation in the mirror of contemporary sources . German Science Publishing House, Berlin 1987.

- Wilhelm Ribhegge: Parliament as a nation, the Frankfurt National Assembly 1848/49 . Droste, Düsseldorf 1998, ISBN 3-7700-0920-7

- Pierer's Universal Lexicon of the Past and Present . 4th edition. Verlagbuchhandlung von HA Pierer , Altenburg 1865 ( zeno.org [accessed on June 18, 2019] Lexicon entry "Germany (Gesch.)", Very extensive information under "XIII. Germany as a Confederation of States / C) From the outbreak of the revolution in March 1848 to the Reactivation of the Federal Assembly ”).

swell

- Franz Wigard (Ed.): Stenographic report on the negotiations of the German constituent national assembly in Frankfurt am Main . Joh. David Sauerländer , Frankfurt am Main 1848. ( Digitization of further volumes in the Munich digitization center ).

- Inventory overview in the Federal Archives Koblenz

Web links

- FNV-Online (database with short biographies of MPs)

- Paper of the Federal Archives ( Memento of August 8, 2004 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 204 kB)

- Information page of the German Bundestag

- Bernhard Wördehoff: Only soldiers help against democrats ; Article on the history of the Frankfurt National Assembly and the reasons for its failure, in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit of June 16, 1989, No. 25/1989, p. 45/46 (www.zeit.de)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Dieter Hein: The Revolution of 1848/49 , CH Beck, Munich 1998, p. 73.

- ↑ Pierer's Universal Lexicon of the Past and Present . 4th edition. Publishing house by HA Pierer , Altenburg 1865 ( zeno.org [accessed on June 18, 2019] encyclopedia entry “National Assembly”).

- ^ Meyer's Large Conversational Lexicon . 6th edition. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1909 ( zeno.org [accessed on June 18, 2019] Lexicon entry “Frankfurter Parlament”).

- ^ Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1806-1866. Volume 1: Citizen World and Strong State. Beck, Munich 1983, p. 609.

- ^ Bernhard Mann: The end of the German National Assembly in 1849 . In: Historische Zeitschrift , Volume 214, Issue 2 (April 1972), pp. 265-309, here pp. 276/277, pp. 279-281.

- ^ Bernhard Mann: The end of the German National Assembly in 1849 . In: Historische Zeitschrift , Volume 214, Issue 2 (April 1972), pp. 265–309, here pp. 291–296.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart a. a. 1988, pp. 858, 860.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 681.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 626-628.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 628/629.

- ^ Simon Kempny: The state financing after the Paulskirche constitution. Investigation of the financial and tax constitutional law of the constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849. Diss., Univ. Münster, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2011, pp. 22/23.

- ^ A b Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 125.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne : The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 51.

- ^ A b c Thomas Nipperdey: German History 1806–1866. Volume 1: Citizen World and Strong State. Beck, Munich 1983, p. 610.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Heinrich Best, Wilhelm Weege: Biographical Handbook of the Members of the Frankfurt National Assembly 1848/49 . Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 483/484.

- ↑ After Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, pp. 40/41.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 54.

- ^ Veit Valentin: History of the German Revolution from 1848–1849. Second volume: Until the end of the popular movement of 1849 . Beltz Quadriga, Weinsheim, Berlin 1998 [1931], pp. 11/12.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society . Second volume: From the reform era to the industrial and political “German double revolution” 1815–1845 / 1849 . Beck, Munich 1987, pp. 739/740. According to another assessment, the proportion of lawyers was 60.4 percent and the proportion of civil servants 37 percent, see Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The Reichsverfassungs der Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 55/56.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society . Second volume: From the reform era to the industrial and political “German double revolution” 1815–1845 / 1849 . Beck, Munich 1987, p. 740.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 54/55.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 57.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), pp. 58/59.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 59.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 590.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. Habil. Bonn 1983, 2nd edition, Luchterhand, Neuwied 1998 (1985), p. 591.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, pp. 55-60, p. 67, with table.

- ↑ Christian Jansen: Unity, Power and Freedom. The Paulskirche left and German politics in the post-revolutionary epoch 1849-1867 . Droste, Düsseldorf 2000, pp. 60/61, p. 64, p. 66, p. 71.

- ^ A b Frank Lorenz Müller: The Revolution of 1848/1849. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, p. 90.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 482/483, p. 846/487.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 485-487.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, pp. 489-493.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 483.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 484, p. 487.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 484.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 127/128.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 128.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 195, p. 197.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 197.

- ↑ Manfred Botzenhart: German Parliamentarism in the Revolutionary Period 1848–1850. Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 1977, p. 489/490.

- ^ After Heinrich Best, Wilhelm Weege: Biographical Handbook of the Members of the Frankfurt National Assembly 1848/49 . Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1998, pp. 404-407.

- ^ Wolfram Siemann: The German Revolution of 1848/49. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1985, p. 225.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn, Helmut Berding: Reforms, Restoration and Revolution 1806-1848 / 1849 (Gebhardt. Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, 10th edition, volume 14). Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2010, p. 574.

- ^ Frank Lorenz Müller: The revolution of 1848/1849. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Bernhard Mann: The end of the German National Assembly in 1849 . In: Historische Zeitschrift , Volume 214, Issue 2 (April 1972), pp. 265-309, here pp. 307/308.