Erfurt Union

The Erfurt Union or German Union was an attempt by Prussia in 1849/50 to replace the German Confederation with a German nation-state . While Prussia was still crushing the revolution of 1848/49 , in May 1849 it invited other German states to join the three kings alliance . The Erfurt draft constitution was a copy of the Frankfurt constitution . But it had been modified in the conservative sense and gave the other princes a more important role.

Originally, this attempt at unification was supposed to found a "German Reich". Because important founding members such as Hanover and Saxony turned away from the project in the course of the months, the nation-state to be founded was renamed "Union" in February 1850. In historical studies one speaks of the "Erfurt Union" because the Erfurt Union Parliament met in the Prussian city of Erfurt .

The Union Parliament met in March and April 1850. It adopted the draft constitution and thus saw the constitution as agreed. Liberal changes were only recommended to governments. However, Prussia only pursued its union project half-heartedly at times, as the highly conservative government found the draft constitution too liberal. Ultimately, Prussia was primarily interested in gaining power. Union was a possible way to do this, but not an end in itself.

In May 1850, only twelve Union states (out of the previous 26) agreed to recognize the Union Constitution as valid. In the autumn crisis of 1850 , Prussia had to give up union politics for good under Austro-Russian pressure. The German Confederation was reactivated in its old form in the summer of 1851.

Designations

In the revolutionary time of 1848/1849, the German state to be established was referred to as the German federal state (in the Central Authority Act ) or later as the German Empire . These names were then also used for the attempt at unification, which became known as the Erfurt Union. The most important treaty on this, the Epiphany Alliance of May 26, 1849, speaks only of an alliance and, alongside it, of an imperial constitution . The attached draft constitution was entitled Constitution for the German Empire , just like its model, the Frankfurt Reich Constitution .

According to the concept of the Gagern double union, the German nation-state should form a further (in the sense of a broader) union together with Austria. This further federation was then called the German Union . This is not to be confused with the federal state, which in February 1850 itself received the official name of the German Union instead of the German Empire . The other names were adapted accordingly.

Beginnings and Epiphany Covenant April / May 1849

Starting position

Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia

Joseph von Radowitz , Prussian general

During the revolution, Friedrich Wilhelm IV repeatedly sent out signals that he was ready to take the helm of a German federal state. The Frankfurt constitution he declined internally, because it was decided by liberals and Democrats. He also wanted a more conservative constitution and shied away from the title of emperor. After all, it was important to him to get the approval of his peers, the other German princes.

His most important advisor on these issues was Joseph von Radowitz , who sat on the right in the Frankfurt National Assembly and still voted to transfer the imperial dignity to the Prussian monarch. Radowitz's current plan of unification came in handy for the king, so as not to take a merely negative stand on the German question. As early as April 3, 1849, when Friedrich Wilhelm IV rejected the imperial crown, he let the other German states know that he wanted to head a German federal state in which those states that so wished should participate.

Acts of Union and Epiphany

Radowitz essentially took over the plan of a double alliance as developed by the liberal Reich Minister President Heinrich von Gagern . According to this, Prussia should form a closer alliance with the other German states, except Austria ( Little Germany ). This closer federation, a federal state, should then be linked with the whole of Austria via another federation. In a memorandum of May 9, the Prussian government offered Austria a “Union Act”. According to this, the German federal state on the one hand and the Austrian monarchy on the other hand would found the "German Union", as an indissoluble union under international law, which would have been similar to the German Confederation, but should be given more powers and an executive: Austria would be in this Directory based in Regensburg and the federal state were represented by two members each, with Austria being allowed to hold the "business chair". But Austria rejected the double alliance.

In addition to Prussia, the four other kingdoms in the German Confederation were represented at a conference in Berlin that began on May 17th: Bavaria, Württemberg, Hanover and Saxony. The southern German kingdoms of Bavaria and Württemberg refused to participate in the state, but Prussia signed the three kings alliance with Saxony and Hanover on May 26th . Saxony and Hanover announced at the time that they would only accede to the later constitution if all German states (except Austria) did so.

The small states in Thuringia , for example , initially felt bound by their commitment to the Frankfurt Constitution. After the final rejection of the Prussian King, the rifts between liberals and democrats became visible, and the unrest in the imperial constitution campaign made the governments and the liberals receptive to Union politics. But there were also skeptical voices, on the one hand because Prussia obviously wanted to expand its power, on the other hand because uprisings could break out in Thuringia if the governments suddenly abandoned the imperial constitution.

But the resistance was slowly overcome. The state parliament in Weimar first voted 20 to 13 on July 21, 1849 for membership. Most recently, Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha joined, for which Duke Ernst II had to dissolve the reluctant state parliament. According to Ernst, only a Prussian-led federal state could meet Germany's security, domestic and economic policy needs.

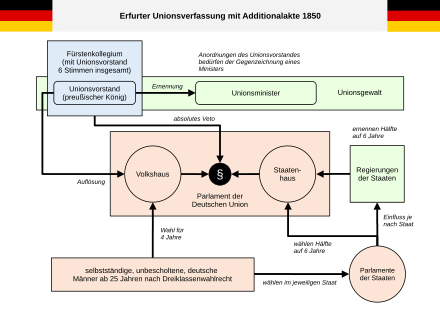

Constitutional documents

The draft constitution, which was published on May 28, 1849, was largely a verbatim copy of the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution, which was just two months older. The catalog of fundamental rights was shortened and partially restricted by legal reservations, and the individual states were to remain more independent. Above all, the Prussian king as emperor would have the title now Empire - and later Union Board was its involvement in legislation have to share with the princes. A college of princes, in which Prussia had one of six votes, would have exercised the power to legislate. Instead of a suspensive veto, as in the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution, the College would even have had an absolute veto, so it could have prevented laws entirely.

An electoral law in Erfurt appeared at the same time as the draft constitution . While the Frankfurt model still provided for a general, equal and direct election, a three-class suffrage was now introduced, which was even stricter than the Prussian. Provisions for an arbitration tribunal based in Erfurt were also published. A June 11 memorandum gave an official interpretation of the draft constitution.

On February 26, 1850, an additional act on the draft constitution was passed. These changes have taken into account the latest developments. The realm was renamed Union , and since Bavaria and other states did not participate, the number of seats for the parliament was adjusted.

Provisional existence

Members

In December 1849, the two Hohenzollern states in southern Germany joined Prussia. This left a total of 36 German countries. Eight of them never joined the Erfurt Union, apart from Austria these were: Bavaria (which had rejected it on May 27, 1849), Württemberg (which declared itself evasive in September), Schleswig and Holstein, Luxembourg-Limburg, Liechtenstein, Hesse-Homburg and Frankfurt. On October 20, Hanover and Saxony were de facto eliminated because the parliamentary elections had been announced against their votes in the administrative council. At the end of 1849 the alliance had as members: Prussia (with Hohenzollern), Kurhessen, Baden, Hessen-Darmstadt, both Mecklenburg, Oldenburg, Nassau, Braunschweig, Saxe-Weimar, Saxe-Altenburg, Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Saxe-Meiningen, Anhalt -Dessau, Anhalt-Köthen, Anhalt-Bernburg, both Schwarzburg, both Lippe, both Reuss, Waldeck, Hamburg, Bremen, Lübeck.

Hanover was formally a member of the Union until February 21, 1850, Saxony until May 25. On June 12th there were still 22 members of the union. Kurhessen, Hessen-Darmstadt, Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Schaumburg-Lippe were missing. At the beginning of August 1850, Baden decided to leave by October 15 at the latest, the expiry of the temporary arrangement.

Board member in the struggle between Prussia and Austria

March / April 1850: Union states (yellow) and states of the Alliance of the Four Kings (red)

As provided for in the alliance treaty, an "administrative council" was set up, which was made up of representatives of the states. One of the main tasks was the preparation of elections. On October 19, he came to convene the Reichstag (the Union Parliament) with the suggestion that it should meet in Erfurt. The unanimous confirmation only followed at a board meeting on November 17th, whereby Prussia had to exert some pressure on representatives of other states. Hanover and Saxony used the elections as an opportunity to assert their reservation against the Union. They ended their work on the Board of Directors on October 9th.

Austria had published its plan for a Greater Austria in March 1849 , according to which its entire territory should join the German Confederation. Austria rejected a national parliament. The restoration of the covenant was initially in his interest. On September 30, 1849, Austria and Prussia reached a compromise on a related issue: after the end of the National Assembly in May, the provisional central authority had continued to exist. Prussia wanted to secure its powers, for example over the federal fortresses and the imperial fleet , but imperial administrator Johann von Österreich insisted on his post. With the agreement of September 30th, a joint Austrian-Prussian federal central commission took over the powers.

That was not in Radowitz's mind, because Prussia recognized the continued existence of the German Confederation. But his king, who saw the federal government as the roof over the future federal state, was in favor. The agreement helped end the revolution. In addition, Prussia gained time for a conservative revision of the draft constitution (the Federal Central Commission should be active until May 1, 1850). In the board of directors, the medium-sized states like Hanover were in favor of this because the relationship between the federal state and Austria could be further clarified, while the small states saw more of a danger for the nation state.

Austria achieved a significant success on February 27, 1850, when the kingdoms of Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and Württemberg, influenced by it, formed the Alliance of the Four Kings . The German Confederation should be brought back to life after a federal reform, with all parts of Austria. That came down to the Greater Austria plan. However, there should be a federal government (a seven-person board of directors) and a parliament, the members of which should be appointed by the state parliaments. This Austro-South German plan offered "the fickle Union states a strong shelter," said Gunther Mai. For tactical reasons, Austria's Prime Minister Schwarzenberg accepted the indirectly elected parliament.

When Hanover formally left the Erfurt Union on February 21, 1850, the Board of Directors filed a complaint with the Union's Federal Arbitration Court on March 4. After all, Hanover and Saxony had signed a treaty with Prussia. However, it was more than questionable that the Union could force a country to abide by the federal government. "The administrative council of the Union resumed its meetings on May 24th, 1850 to initiate the constitution of the provisional college of princes." It met on June 12th.

Union Parliament March / April 1850

At the end of June 1849, the right-wing liberals from the Frankfurt National Assembly met in Gotha to discuss the draft constitution for the Three Kings Alliance. At this “ Gotha post-parliament ” they put their concerns aside in order not to stand in the way of a federal state. The three-tier suffrage in the electoral law even met their ideas in part because it preferred the rich.

The Democrats, on the other hand, sharply rejected the draft and were indignant at the liberals, who had promised in Frankfurt not to deviate from the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution . They then boycotted the elections for the Erfurt Union Parliament at the end of 1849 / beginning of 1850. As a result, the turnout was very low. Because of the boycott and the lower chances of victory for left-wing candidates, liberals in particular were elected, along with conservatives.

The people's house (the lower house , the second chamber) was elected from November 1849 to January 1850 in the individual states by the eligible voters. The members of the House of States, on the other hand, were appointed by the individual states between August 1849 and March 1850. Half of the members of the state house were appointed by the respective state government, the other half by the respective state parliament. If necessary, for example when a member resigned, there could be a by-election.

On March 20, 1850, at the opening of parliament, Radowitz presented the constitutional documents for discussion. The liberal majority in parliament wanted to adopt the draft as a whole, so that the federal state had a constitution immediately and could finally be established. The conservatives, and suddenly the Prussian king, wanted to make the draft even more conservative. Some right-wingers, including Greater Germans, tried to prevent the state entirely.

However, the liberals prevailed. In addition to the constitution, the parliament also accepted amendments proposed by the Liberals, leaving the governments the choice of whether to approve the amendments. This happened at the last session of Parliament on April 29, 1850, which was then postponed. It had only worked six weeks.

End of the Union

Radowitz had to demand a conservative constitutional revision in the Union parliament, against his will. He was pleased that Parliament adopted the draft constitution en bloc . But the resistance of the highly conservative remained, Austria wanted to restore the Bundestag, and Russia signaled its sympathy for Austria. The Kreuzzeitung party with Prussia's Interior Minister Otto von Manteuffel also had doubts about the union project. Radowitz's position depended solely on the influence of the Prussian king; in the spring of 1850 he was politically more or less isolated.

King Friedrich Wilhelm IV invited the representatives of the Union states to Berlin to talk about the adoption of the constitution. 26 members were represented at this royal congress on May 8, 1850, but only twelve wanted to adopt the constitution without reservation. That was not how she came into being. Although it was decided that the Union should exist for two more months for the time being, the project was already over. Interest decreased rapidly on all sides, both among the fickle king and the Prussian establishment as well as among the disappointed liberals.

In the summer and autumn of 1850 Austria was able to bring more and more states behind it. A revived Bundestag met on September 2nd. The Austro-Prussian conflict came to a head when federal troops came to the aid of the beleaguered Prince of Electorate Hesse, while Prussian troops were supposed to protect the military roads in Electorate Hesse, roads that connected the Prussian east and west halves. Radowitz's hour seemed to have come, and for six weeks he was even a member of the Prussian cabinet as Foreign Minister.

But the threatened war in November could be averted. Instead, Austria and Prussia again agreed on cooperation, which was laid down in the Olomouc punctuation of November 29, 1850. The German Confederation was to be fully established again, and Prussia had to finally give up its union policy.

rating

Hans-Ulrich Wehler said that Union policy wanted to bring about a federal state without having to wage a hegemonic war against Austria - “squaring the circle”. This “bold political coup” in the “strategic window” of the spring of 1849, says Gunther Mai as well, but required time and power, in other words the support of the Prussian king. “Radowitz didn't have both, and he let both slip out of his hands.” The Gotha Liberals were also discredited, adds Jörg-Detlef Kühne , whose willingness to compromise was once again misjudged by Prussian politics.

According to David E. Barclay, the contradicting Prussian king wanted a reconciliation of the contradictions of his time: The negative struggle against the revolution could be combined with positive steps towards German unity, Prussia could expand its power to the middle states, while Austria took the lead in Central Europe will be assured. Thus Radowitz's plan found favor with Friedrich Wilhelm, at least for a while, and just as at times it looked as if the plan might succeed. But: "In view of the realities in the Prussian state and the confusion so typical of Friedrich Wilhelm's style of government, the union project never had any greater chance of success [...]." Looking back, according to Barclay, the union project reveals more about these realities than the later founding of the empire and should therefore also to be “examined for oneself”, “not just as a prelude” from 1871.

See also

- German Confederation

- German Empire 1848/1849

- Revolution 1848/1849 in Germany

- Foundation of the North German Confederation

literature

- Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne [u. a.] 2000, ISBN 3-412-02300-0 .

- Jochen Lengemann : The German Parliament (Erfurt Union Parliament) from 1850. A manual: Members, officials, life data, parliamentary groups (= publications of the Historical Commission for Thuringia. Large series, Vol. 6). Urban & Fischer, Jena [a. a.] 2000, ISBN 3-437-31128-X , p. 149.

- Thuringian Landtag Erfurt (Ed.): 150 years of the Erfurt Union Parliament (1850–2000) (= writings on the history of parliamentarism in Thuringia. Issue 15) Wartburg Verlag, Weimar 2000, ISBN 3-86160-515-5 .

Web links

supporting documents

- ^ Warren B. Morris, Jr. : The Road to Olmütz: The Career of Joseph Maria von Radowitz, New York 1976, p. 88.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber : German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , pp. 885-887.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn : "That the federal state must be founded ..." The Thuringian states and the Erfurt Union. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 245–270, here pp. 250–252.

- ↑ Hans-Werner Hahn: "That the federal state must be founded ..." The Thuringian states and the Erfurt Union. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 245–270, here pp. 250–252, 254–256.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , pp. 890-891.

- ↑ See Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , p. 892.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here pp. 40–41.

- ^ Walter Schmidt: The city of Erfurt, its citizens and parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): Erfurter Union and Erfurter Union Parliament. 2000, pp. 433-466, here pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here p. 26.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here pp. 25–26.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , pp. 893-894.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here p. 28.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume 2: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850. 3rd, substantially revised edition, Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, ISBN 3-17-009741-5 , p. 892.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here p. 41.

- ^ Jochen Lengemann: The German Parliament of 1850. Elections, members of parliament, parliamentary groups, presidents, votes. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament. 2000, pp. 307-340, here p. 310.

- ↑ David E. Barclay: Prussia and Union Policy 1849/1850. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 53–80, here p. 74.

- ↑ David E. Barclay: Prussia and Union Policy 1849/1850. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 53–80, here pp. 75–77.

- ↑ David E. Barclay: Prussia and Union Policy 1849/1850. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 53–80, here pp. 77–78.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume 2: From the reform era to the industrial and political “German double revolution” 1815–1845 / 1849. CH Beck, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-406-32262-X , p. 756.

- ↑ Gunther Mai: Erfurt Union and Erfurt Union Parliament. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 9–52, here 18.

- ^ Jörg-Detlef Kühne: The imperial constitution of the Paulskirche. Model and realization in later German legal life. 2nd, revised edition with an afterword added, Luchterhand, Neuwied [u. a.] 1998, ISBN 3-472-03024-0 , p. 87 (also: Bonn, Universität, habilitation paper, 1983).

- ↑ David E. Barclay: Prussia and Union Policy 1849/1850. In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. 2000, pp. 53–80, here pp. 78–80.