Autumn crisis 1850

A politico-military conflict in Germany in 1850 was called the autumn crisis or November crisis.On the one hand, Austria stood opposite those German states that wanted to restore the German Confederation and, on the other hand, Prussia , which was in the process of establishing a new federal state (the Erfurt Union ). This almost led to a war in Germany, which was finally avoided by Prussia's retreat.

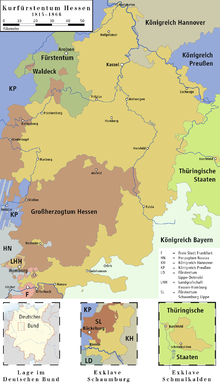

The contrast arose in the spring of 1849: the Prussian king rejected the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution , but promptly made the German states an offer to found a German Empire on a more conservative basis. Due to his half-heartedness, the King had already let this Erfurt Union de facto fail in the spring of 1850, but the conflict with Austria and its allies came to a head in the course of the year. Austria and Bavaria intended to invade Kurhessen on behalf of the German Confederation in order to assist the beleaguered prince there. But the military roads that connected the western part of Prussia ( Rhineland and Westphalia ) with the eastern part ran through Kurhessen . Prussia wanted to protect these streets militarily.

After there had already been a firefight in Kurhessen, the Russian tsar mediated between the two sides. In the event of war, Prussia had to fear democratic uprisings, and Russia would have supported Austria. Therefore, in the Olomouc punctuation of November 29, 1850 , Prussia gave up its union policy and agreed that the German Confederation was restored. Prussia negotiated conferences in Dresden at which a possible federal reform was discussed. However, these conferences only led to small changes, so that in the summer of 1851 the old German Confederation was essentially restored.

German dualism

Habsburg Austria was the main power in the Holy Roman Empire from the end of the Middle Ages . However, by the 18th century at the latest, North German Prussia rose, so that a rivalry developed between the two powers, the so-called German dualism . After 1815, during the time of the German Confederation, Prussia and almost all of its territories belonged to the Confederation, Austria, however, only with its predominantly German-speaking western part. The Bund was essentially a military alliance, but it also served to suppress the liberal, democratic and national movements.

During the revolutionary period of 1848/1849 Austria rejected a German nation-state , whether with or without parts of Austria. Instead, it wanted to see the old German Confederation restored as a pure federation of states, at best with minor changes, but without a national parliament or national executive. Austria's maximum goal was, officially since March 1849, a Greater Austria , i.e. a German confederation including all areas of Austria that had previously been outside the federal government.

Prussia, on the other hand, had given signals during this time that it could envision a small German solution under Prussian leadership, i.e. a Germany without Austria. The Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. Rejected the liberal Frankfurt Imperial Constitution in April 1849 , but immediately proposed a unification project that later became known as the Erfurt Union . Although the smaller states and the kingdoms of Saxony and Hanover joined in May 1849 ( Dreikönigsbündnis ), the two kingdoms fell apart over the months, as did some small states, including the Electorate of Hesse (Electorate of Hesse) in May 1850.

Holstein

In April 1848 the Schleswig-Holsteiners rebelled against their sovereign, the Danish King Friedrich VII . This Schleswig-Holstein uprising led to a war that was interrupted several times by armistices. Prussia and other states intervened on the side of the Schleswig-Holsteiners on behalf of the old Bundestag , i.e. the German Confederation. Denmark, however, received diplomatic support from the great powers Great Britain and Russia.

In early 1849, the German Reich established a governor government in Schleswig-Holstein as the successor to the German Confederation . From July 10, 1849, however, the Schleswig-Holsteiners were on their own, since Prussia had signed an armistice with Denmark. According to him, only Holstein should be governed by the governor government, Schleswig came under a commission controlled by Denmark. In the Peace of Berlin on July 2, 1850, Prussia completely gave up the governor's government: Denmark should restore its rule in Holstein militarily and, if necessary, be allowed to call the German Confederation for help.

Kurhessischer conflict

In February 1850, Elector Friedrich Wilhelm reappointed an ultra-conservative head of government, Ludwig Hassenpflug . Since the state parliament of the Electorate of Hesse did not approve Hassenpflug's budget, the elector dissolved it twice (June 12 and September 2). The elector then decreed the budget in an unconstitutional manner. Because the delegates, the courts and the officials protested against it, the elector placed the country on September 7th, also contrary to the constitution, under a state of war. The lieutenant general commissioned with this referred to his constitutional oath and asked for his dismissal. The entire state apparatus opposed the elector.

In his measures, the elector relied on federal law, primarily on the six articles of June 28, 1832. According to these, the state parliament could not refuse the monarch the means necessary to meet federal obligations. The question about this line of argument was not only whether the six articles justified the breach of the Hessian constitution: on April 2, 1848, the Bundestag had abolished such exceptional laws as the six articles. When the Hessian government fled the capital Kassel on September 12th , it called on the Bundestag to intervene in accordance with Art. 26 of the Vienna Final Act . The federal intervention was intended to forcefully suppress the resistance in Hesse. However, Art. 26 presupposed that an oppressed government itself had behaved in accordance with the constitution.

The events in Kurhessen were of immense importance for Prussia: the western part of Prussia (Rhineland, Westphalia) was geographically separated from the eastern part, and important connecting roads ran through Kurhessen. Since 1834 there was a Prussian-Kurhessian stage convention over two streets, according to which Prussian troops were allowed to use them to march through. It was already a severe blow in May 1850 when the Electorate of Hesse left the Union of Erfurt and instead joined Austria. The Union was thus divided into two halves with no land connection. In addition, Kurhessen would have become a land corridor through which troops of the Bundestag could also reach Holstein via Hanover.

Worsening in autumn

In the course of 1849 and 1850 Austria succeeded in assembling a group of states that saw the old federal law still in force and wanted the Bundestag to act again. Prussia and its allies, on the other hand, rejected the incomplete Bundestag as a "rump Bundestag", which could not exercise the old rights of the Bundestag. However, through the Peace of Berlin in July 1850, Prussia recognized federal law in principle because it had consented to a possible federal intervention in Denmark. During the first months of 1850, the Prussian government had only followed the union project very half-heartedly because the draft constitution was still too liberal for it.

September resolutions and agreement in October

On September 2, 1850, the Bundestag saw itself as renewed, with twelve of the old member states, and prepared the legal requirements for a federal intervention in Holstein, which the Danish king had requested in his capacity as Holstein duke. On October 12th there was again an executive committee to discuss such cases. To this end, the Bundestag sided with the Hessian elector on September 21: the Bundestag reserves all measures to support the elector in restoring his sovereign authority.

Prussia saw the September resolutions of the Bundestag as a threat to its existence and denied their legality. In addition, Kurhessen is still bound by the Union constitution. The adviser to the king and pioneer of the Union, Joseph von Radowitz , was able to warm up Friedrich Wilhelm IV again for the Union; on September 26, 1850, Radowitz even became Prussian Foreign Minister. Meanwhile, Prussia's attitude encouraged the resistance in the Electorate of Hesse, on October 10th almost all officers asked to leave so that the elector's measures would not have to be carried out. Ernst Rudolf Huber refers to the contradiction that on the one hand Prussia placed military discipline above everything and thus successfully put down the revolution of 1849, but on the other hand it was now very interested in the passive resistance of the Hessian army.

Austria and its most powerful allies Bavaria and Württemberg in turn signed the Bregenz Treaty on October 12th . Bavaria undertook the federal intervention in Kurhessen; should Prussia oppose it, the three contracting parties would bring Prussia to its knees with a federal execution . In Prussia the treaty looked like a threat of war. To defuse the conflict, the Prussian Prime Minister Friedrich Wilhelm Graf von Brandenburg and his Austrian counterpart Felix Fürst zu Schwarzenberg met in Warsaw on October 25th . Under Russian pressure, they signed an agreement in which Prussia essentially gave up its policy and in return received the prospect of a future federal reform.

Events in Kurhessen in November

However, the settlement of the conflict was called into question at the beginning of November 1850 by events in Kurhessen. On October 26th, the Bundestag decided to invade, and on November 1st, Bavarian-Austrian troops invaded Kurhessen. In the subsequent quarrel in the Prussian cabinet, the ministers willing to communicate retained the upper hand; Prussia only demanded that Vienna not interfere with the Prussian stage roads in Kurhessen.

Austria, however, demanded that Prussia withdraw its troops in Kurhessen, which were supposed to secure the roads. But that appeared to the Prussian cabinet to be an intolerable imposition. On November 5, Friedrich Wilhelm IV ordered general mobilization . On November 8th there was an exchange of fire between Prussian and Bavarian troops near Bronnzell (south of Fulda); However, officers intervened and prevented further fighting.

On November 21st, the king opened the Prussian state parliament with a bellicose speech in which he justified the mobilization. Three days later, Schwarzenberg issued an ultimatum demanding the complete withdrawal of Prussia from Kurhessen in 48 hours. "War now seemed inevitable," said David E. Barclay. But Otto Theodor von Manteuffel , who had replaced the suddenly deceased Count Brandenburg as Prime Minister on November 6th, reached a meeting with Schwarzenberg through the Austrian envoy in Vienna.

consequences

Prussia avoided the risk of war against federal troops and Russia and finally gave up the Erfurt Union. Radowitz had already left the cabinet on November 2nd. Manteuffel signed the Olomouc puncture with Austria on November 29th . She confirmed the Warsaw Agreement and agreed demobilization on both sides. On December 2, the Prussian cabinet ratified the agreement. The highly conservative Manteuffel emerged stronger from the crisis and remained Prime Minister for eight years; Schwarzenberg, who had never wanted war with Prussia, was also the winner. He just wanted to get rid of the "radicals" (the national conservatives like Radowitz) in the Prussian government and work with the highly conservatives.

The German Confederation should therefore not yet be considered capable of acting. A ministerial conference was to deliberate on questions of restoration and a federal reform demanded by Prussia. At the Dresden Conferences in 1850/1851 , however, neither Austria succeeded in enforcing Greater Austria , nor Prussia in strengthening the German Confederation. The middle states in particular feared an Austro-Prussian unification to their disadvantage. In essence, the old German Confederation was therefore restored in the summer of 1851.

In Kurhessen, Austria indirectly recognized the presence of the Prussian troops. Kassel was to be occupied jointly by Austria and Prussia. Otherwise, Prussia withdrew its troops and Bavaria occupied the country. In Holstein, at the beginning of 1851, an Austrian and a Prussian federal commissioner took over rule from the governor's government and later passed it on to Denmark.

See also

- Erfurt Union

- Greater Austria

- Penal Bavaria

- Schimmel from Bronnzell

- Dresden Conferences 1850/1851

- German War , 1866

Web links

supporting documents

- ^ Manfred Luchterhand: Austria-Hungary and the Prussian Union Policy 1848-1851 . In: Gunther Mai (Ed.): The Erfurt Union and the Erfurt Union Parliament 1850. Böhlau, Cologne [u. a.] 2000, pp. 81-110, here pp. 84-87.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, p. 904 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 908-911.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 909, 911 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 908, 913.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 909, 907.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 909, 912.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 907, 913-915.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 909, 915-917.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, p. 917 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 909, 919.

- ^ David E. Barclay: Frederick William IV and the Prussian Monarchy, 1840-1861 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1995, p. 209.

- ^ David E. Barclay: Frederick William IV and the Prussian Monarchy, 1840-1861 . Oxford University Press, Oxford 1995, pp. 209 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume II: The struggle for unity and freedom 1830 to 1850 . 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, p. 920.