Province of Westphalia

| flag | coat of arms |

|---|---|

|

|

| Situation in Prussia | |

|

|

| Consist | 1815-1946 |

| Provincial capital | Muenster |

| surface | 20,214.8 km² (1939) |

| Residents | 5,209,401 (1939) |

| Population density | 258 inhabitants / km² |

| administration | 3 administrative districts |

| License Plate | IX |

| anthem | Westfalenlied |

| Arose from |

County of Limburg, Principality of Minden, County of Mark Hereditary Principality of Munster, Principality of Paderborn, County of Ravensberg, Sayn-Wittgenstein, County of Tecklenburg, Duchy of Westphalia |

| Incorporated into | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Today part of | North Rhine-Westphalia |

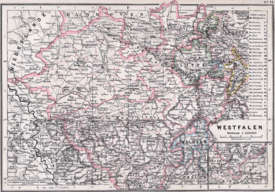

| map | |

|

|

The province of Westphalia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1815 to 1918 and a province of the Free State of Prussia from 1918 to 1946 .

After the Congress of Vienna, the state of Prussia was divided into ten provinces by the decree of April 30, 1815 to improve the establishment of the provincial authorities , one of which was Westphalia. The provincial capital was Münster . In the new province, numerous formerly independent territories with different traditions and denominations were united. A kind of common “Westphalian consciousness” gradually developed, supported by the provincial administration. Nevertheless, the internal differences remained large. In terms of social and economic history, this applies to the different living environments in industrialized, urban Westphalia and agricultural, rural Westphalia. In addition, the denominational boundaries remained of considerable importance. Differences like these were reflected, among other things, in a very differentiated political culture .

Foundation and structure

The emergence of the province of Westphalia was a result of the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The immediate forerunner was the Generalgouvernement between the Weser and the Rhine . Although the Prussian crown had already had territorial possession in Westphalia for a long time, Friedrich Wilhelm III. make no secret of the fact that he would have preferred the incorporation of the Kingdom of Saxony . In fact, with the establishment of the provinces of Westphalia and the Rhine Province, the focus in economic and demographic terms shifted to the west. At the same time, the number of Catholics in Prussia, which was previously almost exclusively Protestant, increased significantly. At the beginning of the development the province had about 1.1 million inhabitants. Of these, about 56% were Catholics and 43% Protestants and about 1% Jews .

The province essentially comprised the territorial parts of the Principality of Minden , which belonged to Prussia before 1800 , the counties of Mark and Ravensberg , Tecklenburg and the Principality of Münster and Paderborn, which came to Prussia after 1802/03, as well as some smaller dominions, including Limburg / Lenne . By the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Prussia was assigned the areas of the Principality of Salm annexed by France in 1810 and the southern parts of the Duchy of Arenberg (formerly Vest Recklinghausen ). In 1816 the Duchy of Westphalia was added. In 1817 the Wittgenstein principalities of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg and Sayn-Wittgenstein-Hohenstein and the Principality of Nassau-Siegen followed .

When it was founded, the new administrative structure, which was created as part of the Prussian reforms, was made up of municipality, district, administrative district and provincial administrations. The administrative integration into the Prussian state was mainly carried out by the first Upper President Ludwig von Vincke . The province of Westphalia consisted of an almost closed area of 20,215 km² (as of 1939) and was administratively divided into the administrative districts of Arnsberg , Minden and Münster . In 1851 and also during the Weimar Republic , the borders of the province were changed slightly.

Overall, the Prussian administration ensured that political institutions and administrative facilities were brought into line. In the legal system, however, there were initially differences. In most parts of Westphalia, the General Land Law (ALR) became the legal basis. In the Duchy of Westphalia and the two Wittgenstein counties, the old regional legal traditions largely continued to apply before the civil code was introduced towards the end of the 19th century with effect from January 1, 1900 .

For the administrative structure, see also administrative districts and districts in Westphalia and for developments at the municipal level, the lists of the municipalities of Westphalia: A – E , F – K , L – R , S – Z

Reactions to the creation of the province

The establishment of the province of Westphalia met with different reactions in the affected regions. In the old Prussian areas such as Minden-Ravensberg or the Grafschaft Mark , there were some demonstrations of joy about the return to the old state association. In the Siegerland , the Protestant denomination facilitated the acceptance of the Prussian government. People in the former Catholic princes of Münster, Paderborn and the Duchy of Westphalia were particularly skeptical of the new sovereigns. The Catholic nobility in particular, who had played a prominent role in the old spiritual states, remained largely negative. Jacob Venedey still spoke of " Musspreußen " twenty years after the founding of the province .

Indeed, the integration into the Prussian state was connected with problems. At the beginning of provincial history, the so-called class lords opposed the administrative standardization . This group of mediatized princes retained special rights well into the 19th century. To some extent they retained the right to judge or oversee schools and churches. The second central problem with regard to legal standardization was the question of the replacement of landlord rights by the peasants within the framework of the peasant liberation . A law was passed in 1820 that made it possible to replace it with cash rents, but there were also numerous individual regulations and regional provisions. The replacement remained controversial until 1848 and regularly led to considerable conflicts on the provincial parliaments of the Vormärz , as it was of particular benefit to the manor owners. The uncertainty of rural property ownership was one of the reasons for the rural unrest at the beginning of the revolution of 1848 . In the longer term, fears that the farmers could be displaced by large estates have not been confirmed. Instead, the two western Prussian provinces remained by far the areas with the lowest share of estates.

At the beginning, the reform policy, which aimed at the implementation of a "bourgeois order", contributed to the acceptance of Prussia. This included the creation of a predictable administration and judiciary, the right to self-administration of the municipalities, the emancipation of the Jews and the liberation of the economy from guild regulations that hinder the market. The educated bourgeois elite not only from Protestant but also from Catholic Westphalia initially recognized the Prussian government as the engine of progress. In the longer term, the merging of such different territories into one province also had identity and awareness-building consequences. In the course of the 19th century people still remembered the past of the old territories, in addition, a Westphalian self-image developed - consciously encouraged by the Prussian government. Of course, this was always in competition with the gradually developing idea of the nation-state.

Westphalian constitutional discussion and restoration time

One of the hopes of bourgeois Westphalian contemporaries such as Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer or Benedikt Waldeck was the early adoption of a constitution. In newspapers such as the "Rheinisch-Westfälischer Anzeiger" or Hermann , the desire for a constitution was initially clearly articulated. Constitutional drafts came from Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer or Arnold Mallinckrodt from Dortmund. Adam Storck and Friedrich von Hövel also took part in the constitutional debate . The benevolent attitude changed significantly with the beginning of the restoration period, the absence of a state constitution and the censorship of the press. The later deputy, Dietrich Wilhelm Landfermann, wrote in 1820: It was not because of the “wretched princely dealings” that they fought in 1813, but because “law and order must be the principle of state life as well as of the bourgeoisie.”

The establishment of provincial parliaments in 1823 did little to change the criticism, as they lacked central parliamentary powers. They did not have the right to obtain a tax permit, were not involved in legislation and essentially only had an advisory role. The MPs were obliged to keep the negotiations confidential and the minutes were subject to censorship.

The first Westphalian provincial assembly met in 1826 in the town hall of Münster . The relatively high turnout shows that the citizens in particular - the lower classes had no right to vote anyway - saw the state parliament as a forum for articulating their interests despite all the restrictions. The Landtag marshal (i.e. the chairman) Freiherr vom Stein did not succeed in restricting the discussions to purely regional questions; rather, the constitutional question played a subliminal role in 1826 and at the next Landtag in 1828. This became even clearer during the provincial parliament of 1830/31, when right at the beginning the deputy for the fourth estate, Franz Anton Bracht and, notably, the noble baron von Fürstenberg , demanded the establishment of a constitution for Prussia. The ideas of what a constitution should look like were very different. Most of the aristocrats, including von Fürstenberg, pleaded for a restoration of the old-class order, while early liberal ideas were put forward by the bourgeoisie. Bracht was supported by Friedrich Harkort and the Münster publisher Johann Hermann Hüffer , among others . Other representatives of the “opposition” were the mayor of Hagen , Christian Dahlenkamp, or the mayor of Telgte , Anton Böhmer . Even among the manor owners there were some liberal voices such as Georg von Vincke .

The district regulations issued in 1827 had also clearly moved away from the spirit of the Prussian reforms. When electing the district administrator, who was basically to come from among the local manor owners, the district estates only had a right of presentation; the appointment was reserved for the king. The town regulations revised in 1831 were hardly less out of date. The right to vote had high hurdles, and the self-governing bodies became de facto state authorities. It looked hardly different with the rural community order.

Westphalia in March

As important as the constitutional question was for Westphalia, for a long time there was little interest in a unified nation-state. The mayor of Rhede und Dingen in Münsterland wrote in 1833: “The meaning of the Hambach Festival and fraternity colors are alien to peace-loving rural dwellers.” Public opinion in the Sauerland or Minden-Ravensberg is likely to have looked little different. It was not until the 1840s that the national movement awoke in Westphalia. Choral societies began to form in many communities, cultivating the national myth; The Westphalian participation in the Cologne Cathedral Festival and the collections for the Hermannsdenkmal were also considerable. Overall, a lively club life developed.

In addition to the disappointment about the largely lacking reforms, the arrest of Archbishop Clemens August Droste zu Vischering in Catholic Westphalia in 1837 during the so-called Cologne turmoil led to a certain politicization of regional Catholicism. The liberal Catholic contemporary journalist Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer put it: [The] “events of the time, like those of the last decade [meaning the Cologne confusion], woke the good-natured Westphalian and contributed not a little to a certain religious slackening (…) At the same time, the popular movement in connection with the turmoil appeared in summer as a harbinger of the revolution of 1848. The “state had to give in, for the first time the violence trembled in front of the voice of the people.” In the 1830s and 1940s also intensified the liberal, democratic and sometimes even socialist discussion groups (e.g. about the magazine "Weserdampfboot", since 1845 Das Westphälische Dampfboot ).

Furthermore, the agricultural reforms, viewed negatively by many rural groups, led to growing dissatisfaction. In addition, there were several poor harvests in the 1840s, which caused food prices to rise significantly, especially in the cities. There were also structural crises in the traditional manufacturing industry. A sign of the sometimes difficult social situation was the high number of emigrants . Between 1845 and 1854 about 30,000 people left the province, mostly for overseas; almost half of them came from the crisis-ridden areas of linen in East Westphalia.

For the socio-economic and historical developments see: Rural Areas and Industrialization

Revolution of 1848/49 in Westphalia

The reactions to the outbreak of the revolution of 1848 were very different in Westphalia. The democratic left in the “Rhedaner Kreis” around the magazine “Westphälisches Dampfboot” celebrated the supposedly new era with euphoria. “The peoples of Europe freed from the oppressive alp that almost took their breath away.” Following the example of the French Revolution, the magazine “Hermann” , published in Hamm , called for the introduction of a new era. The left also leaned against France programmatically and demanded “prosperity, education and freedom for all”. However, there were also opposing opinions, for example from the Bielefeld superintendent and later member of the Prussian national assembly Huchzermeyer . He spoke of a “shameful event” from which the “good-natured Philistine” wrongly expected “that a constitution would put an end to all misery and all injustice.” Instead, he feared the “dissolution of all order ” and general “indecency . "

After the February Revolution in Paris and the March Revolution in various German states as well as in Berlin and Vienna became known, there were unrest among the rural population in parts of Westphalia, especially in the Sauerland , the Wittgensteiner and the Paderborn region . For example, the pension building of Bruchhausen Castle near Olsberg was devastated and the files were burned while singing freedom songs. Other castles like in Dülmen were also devastated. This rural uprising was quickly put down by the military. In the early industrialized areas of Westphalia, such as the County of Mark, factories were stormed in some places. In the cities, on the other hand, after the appointment of liberal March ministries , people saw themselves at the goal of political wishes and celebrated the victory of the revolution almost everywhere with parades and the hoisting of the black, red and gold flag. In addition, there was an influential anti-revolutionary trend, especially in the old Prussian regions; in the county of Mark especially about the entrepreneur Friedrich Harkort , who promoted his views with his well-known workers' letters.

In the elections to the national assemblies in Berlin and Frankfurt , the political direction of the candidates was not the decisive element, but their reputation in the population played a central role in the nomination. In the Sauerland, therefore, politically different people (who did not necessarily have to come from the constituencies) were elected, such as the conservative Joseph von Radowitz , Johann Friedrich Sommer, who vacillates between liberalism and ultramontan ideology, or the democrat Carl Johann Ludwig Dham . Leading Westphalians in the Berlin National Assembly were among others the Democrats Benedikt Waldeck and Jodocus Temme . In Berlin, Waldeck ( Charte Waldeck ) on the left and Sommer on the right played a significant role in the constitutional discussion .

In Frankfurt, Westphalia was represented by the liberals Georg von Vincke , Gustav Höfken or the later Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler , among others . Political clubs and newspapers of all political stripes were formed in the region itself. The spectrum ranged from Catholic and liberal papers to the radical democratic Neue Rheinische Zeitung . The spectrum of political opinion was just as diverse as the press landscape. Conservative alliances were an exception and mostly comprised only Protestant officers and civil servants in the government and garrison towns. A certain exception was the conservative attitude of the rural population in the Pietist-Protestant milieu in Minden-Ravensberg. The vast majority of politically active citizens found themselves in constitutional or democratic clubs. In July 1848, at a congress in Dortmund, the Liberals founded an umbrella organization of constitutional associations responsible for the provinces of Rhineland and Westphalia. In the administrative district of Arnsberg alone there were 28 associations in October, in the two other administrative districts their number was significantly lower and in Münster the local association had broken down due to internal conflicts. It was not until September 1848 that the democratic associations also managed to come to an agreement at a congress. In Münster the local democratic association had more than 350 members. The labor movement in the form of the General German Workers' Brotherhood was only sparsely represented compared to the Rhine Province. There was a strong workers 'association in Hamm, which played a leading role in the Westphalian Democrats and at the same time maintained contact with the workers' brotherhood. Overall, the number of democratic or republican associations initially remained significantly lower than that of liberals. In the Catholic parts of Westphalia, the first organizations of political Catholicism also formed. These so-called Pius societies , which arose in many places, were programmatically based on the society of the provincial capital.

In petitions, professional groups and local councils asked their MPs to represent certain demands in the national assemblies. In the months that followed, political excitement declined noticeably. In Catholic areas in particular, the election of Archduke Johann as Reich Administrator by the Frankfurt National Assembly met with great approval and was celebrated with patriotic festivals in Winterberg and Münster , for example . However, the reaction to this election shows how great the difference still was between Catholic and Protestant Westphalia. In the old Prussian territories this was seen as a step towards a unified German state, but it was above all Prussia's duty to enforce unity and freedom. In Catholic Westphalia, however, the decision of the National Assembly was seen as a step towards a unified state under Catholic leadership. In this respect, the opposition between supporters of a small German and a large German solution to the German question overlapped with the regional confessional boundaries.

It was not until the beginning of the counter-revolution that the political excitement increased significantly. In many areas of Westphalia, the importance of the democratic movement increased, while hesitant old liberals like Johann Sommer clearly felt the resentment of the population. In Westphalia, faced with the threat of revolutionary achievement, democrats and constitutional liberals worked together, which culminated in the “Congress for the Cause and Rights of the Prussian National Assembly and the Prussian People” in Münster in November 1848. After the dissolution of the Prussian National Assembly, democratic candidates such as Johann Matthias Gierse won the election for the second Prussian Chamber in many parts of Westphalia . The climax and end point of the revolution in Westphalia was the violent suppression of the Iserlohn uprising . Some leading Westphalian revolutionaries such as Temme or Waldeck were later politically persecuted by the authorities. In the summer of 1849 the first Westphalian Democrats emigrated to America.

Rural areas and industrialization in Westphalia

Pre-industrial times

At the beginning of the 19th century, Westphalia was an extraordinarily diverse region, both economically and socially. Agriculture was predominant, and in many places it was still very traditional and ineffective. In most areas, small and medium-sized peasant livelihoods dominated. Larger farms were only widespread in the Münster and Paderborn regions. These areas as well as the Soest Börde were also particularly suitable for agriculture. In contrast, agriculture in Minden-Ravensberg and in the southern highlands was not very productive. Even in pre-industrial times, some of the country's products were sold outside the country. The export of Westphalian ham is well known. The industrialization favored the market integration of agriculture with the industrial conurbations. The demand led to the expansion of pig breeding. The grain produced in the province was an important raw material for the brewing industry that was initially emerging in the Ruhr area and later in other parts of the world . In Dortmund alone there were verifiably more than 80 individual breweries. The proximity to the industrial areas as a sales market contributed to the fact that in the agriculturally useful parts of the region, agriculture remained the dominant and definitely profitable branch of the economy well into the 20th century.

In many places, the yields at the beginning of the 19th century were often insufficient to adequately feed the population, which has been growing since the 18th century. The number of the poor and landless increased. Many looked for opportunities to earn money outside of their homes. The Kiepenkerle , who have become the symbol of the country, and the Sauerland traveling traders moved around as traders . The people who went to Holland in the northern parts of the province and the wandering brickmakers in East Westphalia and the neighboring country of Lippe earned their living as migrant workers. The trade in the dead developed out of the Holland walk , in which especially the linen made by home workers during the winter was sold in Holland the following summer.

In Westphalia, the cheap labor facilitated the upswing of pre-industrial businesses that produced for a supra-local market. In the north-west German linen belt , which stretched from western Münsterland via Tecklenburg, Osnabrück, Minden-Ravensberg to what is now Lower Saxony, home work gave rise to a proto-industry . In Minden-Ravensberg in particular , pre-industrial linen production played an important role. The fabrics were bought and sold by so-called publishers.

In South Westphalia , including the Siegerland , parts of the Duchy of Westphalia and the Brandenburg Sauerland, there was an iron producing and processing region based on the division of labor, which continued beyond the provincial border in the Bergisches Land and in the Altenkirchen district . The ore extracted mainly from mining in Siegerland and East Sauerland was smelted (e.g. Wendener Hütte ) and processed into finished goods in the west of the region (e.g. wire drawing works in Altena , Iserlohn and Lüdenscheid or the Iserlohn sewing needle production ). Some of these trades were organized as a corporate and publishing system ( Reidemeister ). In the southern part of what will later become the Ruhr area, hard coal has been mined for the neighboring industrial regions for a long time. The Alte Haase colliery is an example of this .

industrialization

Parts of the area of the province became a pioneer of the industrial revolution in Germany in the first decades of the 19th century and were among the economic centers of the German Empire during the period of high industrialization .

The end of the continental barrier opened the region to English industrial products. In the long term, home textile production in particular was unable to cope with this competition and eventually disappeared from the market. By changing over to industrial production in good time, it was possible to adapt to the new era in and around Bielefeld. The Ravensberger spinning mill (founded in 1854 by Hermann Delius ) was the largest flax spinning mill in Europe. In 1862 the "Bielefelder Actiengesellschaft für mechanical weaving company" followed. Later, the demand from textile companies was a reason for the emergence of an iron and metal processing industry in this area.

However, the new mechanized industry could not employ the same labor force as the old domestic industry. Especially in the linen areas of Westphalia, pauperism and the emigration of the rural lower classes overseas in the Vormärz were a widespread phenomenon.

In the iron and metal processing areas of South Westphalia, industrial competition from abroad initially had only limited negative effects. Pre-industrial sheet metal production in and around Olpe disappeared from the market .

More dangerous for the old smelters and hammer mills was the emergence of an industry in Westphalia itself, which was working with modern resources at the time. Its basis was the hard coal found in the later Ruhr area. Decisive for the development of the Ruhr mining was the formation of the underground mines, which also allowed mining below the marl layer. This first happened in 1837 near Essen in the Rhenish Ruhr area. In Westphalia, the Zeche President near Bochum was the first of its kind in 1841.

Friedrich Harkort and Heinrich Kamp founded a mechanical workshop in Wetter in 1818 and the first puddling plant in Westphalia in 1826 at the same location . The plant was later relocated to Dortmund and the Rothe Erde ironworks developed from it . Similar foundations soon followed in Hüsten ( Hüstener union ), Warstein , Lünen ( Westfalia Hütte ), Hörde ( Hermannshütte ), Haspe ( Hasper Hütte ), Bochum ( Bochumer Verein ) and other places. These new coal-producing companies were significantly more productive than the pre-industrial companies that relied on expensive charcoal.

The expansion of the transport infrastructure was a prerequisite for industrial development. The construction of paved artificial roads began at the end of the 18th century , as well as making the rivers navigable, especially in the lower reaches of the Ruhr, and building canals. Above all, however, the railway construction became the engine of the industrial boom. In 1847 the main line of the Cologne-Minden Railway Company running west-east from the Rhine to the Weser was completed. Only two years later, the routes of the Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft followed and, since 1850, those of the Königlich-Westfälische Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft .

Sub-regions such as the Sauerland, which were only connected to the railroad network in the 1860s or 1870s, were therefore sidelined in terms of economic geography in the age of economic expansion. In parts of these regions there was a veritable de-industrialization process. In their place came the now rational forestry in many places. There were only a few places where new industrial developments occurred, such as in Schmallenberg with a focus on the hosiery industry . With a downward trend, mining continued .

In the further course of the century, the coal and steel industry increasingly shifted to the vicinity of the coal mines in the Ruhr area. The Hermannshütte, the Rothe Erde company , the Aplerbecker Hütte , the Hörder Bergwerks- und Hütten-Verein and the Henrichshütte near Hattingen have been in existence since the 1850s . As a result, some of the early industrialized areas in South Westphalia were sidelined and in many cases could only hold their own by concentrating on special products (e.g. sheet metal production in Hüsten ). In the decades that followed, numerous new collieries and mining operations such as the Schalker Verein were built in the Ruhr area . In addition, older factories grew into huge factories with many thousands of employees. By the middle of the 19th century at the latest, the Westphalian part of the Ruhr area with its coal mines and the mining industry had become the clear economic center of the entire province.

Population growth and social change

The jobs created initially attracted a large number of job seekers, mainly from the rural and economically stagnant parts of the province. Since around the 1870s, the workforce in Westphalia was largely exhausted and the companies recruited more and more workers from the eastern provinces of Prussia and beyond. Separate associations, trade unions and pastoral care in their mother tongue were created for the large number of Polish- speaking workers. This created a special type of population in the area, which differed from the Westphalian region in some aspects, such as the language . In 1871 the province of Westphalia had 1.78 million inhabitants, which was around 14% more than in 1858. By 1882 the population rose by more than 20% and the increase was similarly high until 1895. In the next ten years until 1905 it increased the population then increased by more than 30% to more than 3.6 million. The administrative district of Arnsberg experienced the strongest growth, where the Westphalian industrial communities concentrated. The population in the administrative districts of Münster and Minden rose from 1818 to 1905 by a little more than 100%, in the administrative district of Arnsberg it was over 400%.

| year | Population (million) |

|---|---|

| 1816 | 1.066 |

| 1849 | 1.489 |

| 1871 | 1.775 |

| 1880 | 2.043 |

| 1890 | 2,413 |

| 1900 | 3.137 |

| 1910 | 4.125 |

| 1925 | 4,784 |

| 1939 | 5.209 |

Above all in the Ruhr area, but also to a lesser extent in the other industrializing parts of Westphalia, the social consequences of industrialization were considerable. In these areas, the working population became by far the largest social group. Due to immigration, the population grew at times by leaps and bounds; there was a lack of cheap living space and in the Ruhr area in particular, boarders and sleepers were a widespread phenomenon. In some cases, the companies tried to put an end to this need with company apartments or miners' colonies. The ulterior motive was, of course, the formation of a workforce loyal to the company, which should thus be kept away from the labor movement .

Due to the population growth, a number of cities and towns developed into large cities. While cities like Dortmund or Bochum could look back on an old urban tradition, places like Gelsenkirchen or Recklinghausen grew from small-town or village-like dimensions to large cities within a few decades. But also Witten , Hamm , Iserlohn , Lüdenscheid and above all Hagen , now on the edge of the area, as well as Bielefeld developed into industrial cities.

Infrastructure and limits of urban life

A characteristic of the rapidly growing industrial cities was the extensive lack of a middle class. The middle class was weak. The cities initially concentrated on the most necessary infrastructure measures such as supply and disposal facilities, local public transport, schools and the like. By improving the hygienic conditions, mortality, especially child mortality, fell significantly. Epidemics like cholera no longer played a significant role. On the other hand, tuberculosis , which was widespread for a long time , work-related diseases such as silicosis in miners and, in general, environmental pollution from mining and industry, showed that this positive development also had its limits.

Only later did the new district towns have cultural facilities such as museums or theaters. These concentrated on the cities with a certain bourgeois tradition, while they were absent in the rapidly growing clustered industrial villages well into the 20th century. A deficit of the Westphalian city system as a whole was the poorly developed higher education system. There were universities in Münster and Paderborn as early as the 18th century , but since the beginning of the Prussian era these were only “rump universities” with a limited range of courses. It was not until 1902 that the academy in Münster was raised to a full university again. In the metropolitan areas of the Ruhr area, the expansion of the higher education system essentially only began as part of the educational expansion in West Germany since the 1960s.

Social upheaval and trade unions

With the introduction of the general mining law of 1865, the previous privileges of the miners ended , and since then the miners have hardly differed from other groups of workers in terms of labor law. Initially, they reacted to wage cuts, working hours extensions, etc. as usual with petitions - mostly unsuccessful - to the authorities. Increasingly, people began to orientate themselves towards the forms of action of other groups of workers. As early as 1872 there was the first locally limited, unsuccessful miners' strike in the Ruhr area .

In 1889 the tensions that had been pent up for decades were released in a strike , in which around 90% of the 104,000 miners at the time took part. The strike began in Bochum (April 24th) and Essen (May 1st). Numerous other employees spontaneously joined this. A central strike committee was formed. The workers demanded wage increases, the introduction of the eight-hour day and numerous other demands. The fact that the strike committee sent a deputation to Wilhelm II shows that the old government tradition in mining was not forgotten . Although the latter criticized the strike, he admitted that he would have the complaints officially examined. Since at the same time the association signaled concession for mining interests , the strike gradually subsided.

In the same year, the strike in the Westphalian and Rhenish coal districts served as a model for the miners in the Sauerland , in the Aachen district and even in Silesia . The strike also made it clear that organizations were needed to represent interests. On August 18, 1889, the so-called Old Association was founded in Dortmund-Dorstfeld to differentiate between other unions . The Christian Miners' Association followed in 1894, and a Polish Association was founded in 1902. The Hirsch-Duncker trade unions had made organizational attempts since the 1880s, but remained insignificant. The miners were also role models for other professional groups in terms of trade union formation.

In 1905, starting again from the Bochum area, there was an extensive strike movement which ultimately led to a general strike by all miners' unions. Overall, around 78% of the miners in the area took part in this movement. Although the strike had to be broken off, it was indirectly successful in that the Prussian government, by amending the General Mining Act, met many of the workers' demands. In 1912, the Triple Alliance strike, a wage movement supported by the Old Association, the Polish trade union and the Hirsch-Duncker Association, while the Christian Miners' Association refused to participate. Therefore the share of the insurgents was only 60%. The strike was carried out with great bitterness, and violent riots ultimately led to the deployment of the police and the military. Ultimately, unsuccessfully, the movement had to be stopped.

In addition to the miners, workers from other industries also fought industrial action in Westphalia. In the metal industry these tended to be concentrated on small and medium-sized enterprises, while in large-scale industry the labor movement was barely able to gain a foothold for various reasons. Companies in the iron and steel industry in particular defended their "master of the house" position with layoffs if necessary. This was made easier for them by a highly differentiated internal structure, which prevented the emergence of a community awareness comparable to that in mining.

Political culture in the German Empire and during the Weimar Republic

The political culture of Westphalia, which is mainly reflected in the long-term development of the election results, was closely related to the different denominational and social structures, but also to the political traditions of the first half of the 19th century. The denominational structure in particular played a central role in Westphalia's development. As in the whole of Germany, Catholic and social democratic milieus were formed in varying degrees , which, with their organizational system, had a major impact on the lives of their followers "from cradle to grave". This was less clear with liberals and conservatives . On August 1, 1886, the districts and independent cities of Westphalia formed the Provincial Association of the Province of Westphalia , a corporation whose representative body was now the Westphalian Provincial Parliament, which was previously occupied by estates. The provincial parliament, now consisting of elected representatives of the districts and independent cities, thus became a mirror of the political groupings in the districts and cities, provided that the three-class suffrage allowed this. The provincial parliament elected the state director as head of government of Westphalia, and from 1889 the name was changed to governor.

center

Especially since the Kulturkampf , the Center Party was able to largely monopolize the political landscape in the Catholic parts of the province, following on from the traditions of the Vormärz and the revolution of 1848/49. Based on the denomination, the party was elected almost independently of the respective social status, from the Catholic workers, the rural population, the bourgeoisie to the nobility. Westphalia was one of the core areas of this party. It was probably not by chance that some politicians met in Soest in the 1860s to discuss the establishment of a Catholic party. The Soest program from 1870 is considered one of the founding documents of the center. With Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler and Hermann von Mallinckrodt , leading politicians from the founding phase came from the province of Westphalia.

Within political Catholicism, the social differences became clearly noticeable in a regionally differentiated orientation of the party since the 1890s . In predominantly rural areas, the center was often rather conservative. The Westphalian Farmers' Association played an influential role there. He mainly represented small and medium-sized farmers; the country nobility was influential well into the Weimar Republic and was also able to assert itself politically. In the Münster-Coesfeld constituency, for example, Georg Friedrich von Hertling , who later became Bavarian Prime Minister and Reich Chancellor, ran for the Reichstag from 1903 to 1912. It was no coincidence that the later Chancellor Franz von Papen , who stood on the far right wing of the center, came from the more agrarian Werl and had his political base in the Münsterland .

In contrast, in industrial parts of the province, social Catholicism was particularly strong. This variant played an important role in the Ruhr area and the Sauerland in particular. The Christian trade unions, for example, were usually stronger there than the social democratic competition; Leading socio-politically committed Catholics such as August Pieper and Franz Wärme , both of whom were leaders in the Volksverein for Catholic Germany , came from Westphalia.

In addition to general secularization tendencies, the social orientation of political Catholicism was one of the reasons why the center lost support among medium-sized circles during the crisis-ridden Weimar Republic . In the Sauerland, for example, the party lost around 20% of its original share of the vote from 1919 to 1933. Nonetheless, it usually remained the leading political force in the Catholic areas and was even able to easily gain in Münster in the 1930 Reichstag elections , which was probably due to local patriotic reasons as well as political as well as Chancellor Heinrich Brüning , who was appointed on March 29, 1930, came from Münster .

Social Democrats and Communists

The consequence of the dominance of the center in Westphalia meant that political liberalism, conservatism and social democracy were essentially restricted to Protestant Westphalia. It was no coincidence that some leading politicians from the early days of Social Democracy such as Carl Wilhelm Tölcke or Wilhelm Hasenclever came from the Catholic Sauerland, but began their political careers in the neighboring Protestant regions.

The Brandenburg Sauerland and the area around Bielefeld were early strongholds of social democracy. The ADAV of Ferdinand Lassalle and his successors was particularly strong in the Brandenburg area . It was mainly thanks to Tölcke's work that the party had local clubs in Iserlohn, Hagen, Gelsenkirchen, Bochum, Minden and Oeynhausen by 1875. After the merger of ADAV and SDAP , Tölcke ran as a candidate for the new SAP as the top candidate for Westphalia. In Bielefeld, personalities like Carl Severing from the German Empire to the first years of the Federal Republic played a major role in shaping political life.

The Westphalian Ruhr area was by no means a "heart chamber" of the SPD before 1933. Although the social democratic so-called Old Association was the first miners' union, the Christian competition was hardly weaker since the turn of the 20th century, to which an equally important Polish organization later joined. Only in predominantly Protestant parts of the area - such as in Dortmund - was the SPD able to achieve significant strength before the First World War. In the Ruhr area, the miners' leaders Otto Hue and Fritz Husemann were also central figures in social democracy.

The SPD was hit by the crises of the Weimar Republic even more directly than the Center Party. Disappointment with the party's attitude during the Ruhrkampf (1920), for example , the plight of inflation and the global economic crisis drove numerous workers into the ranks of the extreme left, some of them initially in their syndicalist and later in their communist form. In the area, the KPD was a mass party even before the global economic crisis, while the SPD fell behind in many cases.

Liberals and Conservatives

During the German Empire, the SPD was unable to monopolize the political landscape in large cities like Dortmund or Bielefeld with a notable bourgeoisie and a comparatively strong middle class. This was opposed not only by the three-tier suffrage, but also by considerable liberal and conservative forces.

Some of these even reached the working class. In the Siegerland, for example, the Protestant working-class population remained conservative for a long time or adhered to the Christian Social Party of the anti-Semite Adolf Stoecker . In 1881 he also accepted the mandate of the constituency of Siegen-Wittgenstein-Biedenkopf in the Reichstag. It was only during the Weimar Republic that the socialist parties really managed to gain a foothold there.

Minden-Ravensberg remained a stronghold of the German Conservative Party until the 1912 Reichstag election . Then the constituency of Minden-Lübbecke fell to the left-liberal Progressive People's Party .

The south of the old county of Mark and in particular the Reichstag constituency of Hagen-Schwelm was a stronghold of liberalism, especially the left-wing liberal German Liberal Party of Eugen Richter , who also held the Reichstag mandate there until 1906.

Without a stable milieu encompassing all areas of life, it was above all the former voters of the liberals and conservatives who went over to the National Socialists during the Great Depression .

First World War and Weimar Republic

World War and Revolution

In Westphalia too, at the beginning of the First World War, there was predominantly national exuberance. In contrast to the widespread war skepticism in 1866 and 1870/71, the enthusiasm at first glance not only gripped the Protestant but also the Catholic parts of the province and did not stop at the working class. The local newspaper reported from Arnsberg on the occasion of the Austrian mobilization: “Suddenly someone started singing Deutschland, Deutschland über alles and the crowd immediately joined in with enthusiasm. (...) Meanwhile, several troops marched through the streets, expressing their sympathy for the allied Danube monarchy and their enthusiasm for war by singing patriotic songs. Loud demonstrations of enthusiasm poured out of the crowded pubs. It wasn't until late at night that it finally got quiet. ”The reports were similar in other parts of the province. In the meantime, this one-sided picture of a general enthusiasm for war is differentiated. Fears of war and worries about the future were widespread, especially in rural or small-town regions. Corresponding examples can also be found for Westphalia.

Everyday life in the war, especially the brief phase of increased unemployment immediately after the start of the war, rising prices, food shortages and hunger in industrial cities during the second half of the war quickly dampened the initial enthusiasm. Gradually, the existing political system also began to lose legitimacy in the province. Within the social democratic labor movement, criticism of the so-called Burgfriedenspolitik led to the split of the USPD in 1917 . Although the number of members of the SPD fell sharply everywhere in Westphalia, only a few local associations such as in Hagen and Schwelm went over to the new party. The Center Party, which is important for Westphalia, supported the monarchical government at its head until the end, but among its voters, war fatigue also spread more and more.

Since the beginning of 1918, social unrest and numerous strikes in various parts of the province also increased in Westphalia. The real revolution, of course, came from outside. On November 8, 1918 mutinous sailors of the high seas reached Westphalia by train. They were joined by the troops of the local garrisons in Bielefeld, Munster and soon in the entire province, and workers 'and soldiers' councils were formed everywhere . Initially, the majority of them were behind the revolutionary government of Friedrich Ebert and advocated parliamentary democracy. In Westphalia, its participants were mainly made up of supporters of the social democratic parties. In some of the Catholic areas, members of the Christian trade unions also took part. The broad support for the revolution changed in the run-up to the national assembly elections when the Catholics turned against the new "Kulturkampf" of Minister Adolph Hoffmann (USPD). At times there was even sympathy for the establishment of an independent "Rhenish-Westphalian Republic".

The province in the Weimar Republic

| year | center | SPD | DVP | DNVP | KPD | DDP | NSDAP | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 35.5 | 24.7 | 13.0 | 8.8 | 7.3 | 4.4 | - | 6.3 |

| 1925 | 35.1 | 22.8 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 9.3 | 2.7 | - | 2.2 |

| 1929 | 32.9 | 22.1 | 8.7 | 6.3 | 9.3 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 12.5 |

| 1933 | 28.2 | 15.1 | - | 6.8 | 10.3 | - | 36.2 | 2.3 |

| Source: | ||||||||

In January, parts of the Westphalian workers 'and soldiers' councils began to radicalize. Together with the campaign for the socialization of mining, there was a broad strike movement in the Rhenish and Westphalian Ruhr areas. On the political rights of the regular General Command began to arrangement in Munster in the province volunteer corps forming. When they began to crack down on the strikers, the strike peaked with 400,000 strikers across the district. Outwardly, the calm was restored by Carl Severing - the leading Bielefeld Social Democrat and Prussian State Commissioner - without really easing the situation.

As early as the beginning of the Kapp Putsch in March 1920, not only strikes broke out in cities in the Ruhr area such as Bochum , Wetter , Witten , Herne , Haltern , but also in Hagen, not only as everywhere in the Reich, but also in some cases violent unrest, with the workers fighting quite successfully the Freikorps turned. The workers were mostly supporters of the USPD, the KPD and the syndicalist FAUD . After Kapp's surrender, the workers' militias did not lay down their arms; rather, a "Red Ruhr Army" of up to 100,000 men emerged, which largely controlled the Ruhr area and advanced far into the Münsterland. Severing succeeded in reaching an armistice, but the Reichswehr troops and Freikorps, which had been drawn together from all over the Reich, took violent action against the rebels. The uprising collapsed on April 8, 1920, with high casualties, especially on the part of the workers. In the course of the democratization of Prussia, the Westphalian provincial parliament was determined from 1921 by general popular elections and no longer by elections of representatives of districts and independent cities.

The normalization in the Ruhr area was only temporary, however, since French and Belgian troops had occupied the area as far as the Lippe since January 11, 1923. This started the so-called Ruhr War . The consequence was the proclamation of passive resistance by the imperial government, which however had to be broken off in the end. The cost of it was a key factor in the onset of hyperinflation . In the period of inflation, the province of Westphalia coined its own emergency money with the portraits of Annette von Droste-Hülshoff , Freiherr vom Stein and the heraldic animal "Westfalenroß" up to a nominal value of one trillion . However, only the nominal values from 1921 ranging from 50 pfennigs to 10 marks were used as emergency money. The other emergency coins are "medal-like".

After the currency reform of 1923, the political and economic conditions in the province stabilized for a few years. However, in 1928, the Ruhreisenstreit and the lockout of 200,000 workers made it clear how fragile the social peace was.

Imperial and local reforms

During the Weimar Republic , discussions about imperial reform also called into question the previous territorial existence of the province. In defense, the provincial administration relied on folklore and historical legitimation of a historical "Westphalia area". This led to the publication of a multi-volume work of the same name from 1931. This investigated the question of whether there was an area of Westphalia in northwest Germany that would be different from other parts of this geographic area. The result was not entirely clear. However, it was agreed that the state of Lippe, the administrative district of Osnabrück, parts of the state of Oldenburg and some other areas outside the province would belong to the historical "Westphalia region".

During the republic, incorporation and with it the urbanization that had started in Münster in 1875 continued and reached its climax in 1929 with the law on the municipal reorganization of the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area . A whole series of rural districts (e.g. Dortmund, Hörde, Bochum) were dissolved and the associated areas were mostly assigned to the larger, now mostly independent, cities. In addition, with the Ennepe-Ruhrkreis and the city of Oberhausen, new territorial structures emerged. The Ruhr coal district settlement association founded in 1920 as a communal union of the Ruhr area cities was also new .

Westphalia in the time of National Socialism

As in Germany as a whole, the NSDAP in Westphalia was still a completely insignificant splinter party in the 1928 Reichstag election . In the administrative district of Arnsberg it came to only 1.6%. In the course of the global economic crisis , however, the party's importance increased rapidly. In the Arnsberg district it already achieved almost 14% in 1930. However, there were considerable differences, mainly depending on the social and religious structure. While the NSDAP reached almost 44% of the Reichstag average in the last halfway free Reichstag election , it was only 28.7% in the (predominantly Catholic) administrative district of Münster, 33.8% in the (mixed confessional) administrative district of Arnsberg and 40 in the (predominantly Protestant) administrative district of Minden , 7%.

| area | NSDAP | SPD | KPD | center | DNVP | DVP | DDP | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iserlohn district | 40.35 | 16.36 | 16.01 | 16.58 | 6.39 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 3.18 |

| City of Lüdenscheid | 32.75 | 20.79 | 22.85 | 6.87 | 9.19 | 1.61 | 1.63 | 4.32 |

| Meschede district | 23.14 | 3.06 | 6.49 | 60.99 | 5.68 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| District of Olpe | 14.34 | 6.88 | 5.83 | 69.12 | 3.29 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

One of the main characteristics of the history of the province between 1933 and 1945 was that the development in the course of the Gleichschaltung and the establishment of the dictatorship hardly differed from other parts of Germany. The new rulers were able to fall back on the already numerically strong NSDAP Gaue Westfalen-Nord (seat of Münster) under the Gauleiter Alfred Meyer (since 1938 also chief president) and Westphalia-Süd (seat of Bochum) under Josef Wagner .

Harmonization and enforcement of the dictatorship

Immediately after the seizure of power, politicians and officials who were close to the center or the SPD were dismissed. One of these was the Arnsberg District President Max König (SPD). Some district administrators or mayors such as Karl Zuhorn in Münster, Curt Heinrich Täger in Herne and Cuno Raabe in Hagen were removed from office not least because they refused to hoist the swastika flag on the roofs of the town hall. The governor Franz Dieckmann (center) was dismissed and replaced by the National Socialist Karl-Friedrich Kolbow . The Ober-President Johannes Gronowski (center) was also dismissed . This was replaced by the national conservative Ferdinand Freiherr von Lüninck . His person is unusual because he was a Catholic member of the DNVP . As a non-National Socialist, he helped to increase the acceptance of the regime in Westphalia and implemented the government's measures in the first few years.

Numerous supporters and functionaries - especially those of the workers' parties - were arrested and at least temporarily sent to a concentration camp . The population in numerous communities in Westphalia also participated in the boycott of Jewish shops on April 1st. After May 1, 1933, the union houses of the free unions were also occupied in Westphalia. As a result, the local union leader killed himself in Neheim. On May 10, 1933, books were burned in provincial cities such as Münster.

Adjustment and resistance

As everywhere, the majority of the population willingly adapted to the demands of the regime to a not inconsiderable extent. The Christian unions, which are strong in the province, hoped to be able to take the place of the banned free organizations at short notice and made submissive remarks to the National Socialists before they too were absorbed into the German Labor Front .

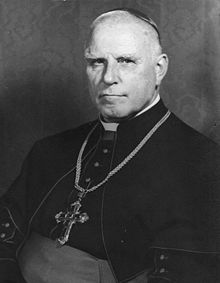

Those who actively resisted were a small minority in Westphalia too. A strong motive for them was religious affiliation. About a thousand priests of the Catholic Church suffered at least temporary arrests or persecution. Some were sent to concentration camps; at least 15 died there. The resignation of Oberpräsident Ferdinand Lüninck in 1938 and his subsequent execution in connection with the assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944 were also religiously motivated. This is also documented in the statement of the lawyer Josef Wirmer , who was born in Paderborn and grew up in Warburg , who replied to chairman Roland Freisler during the trial before the People's Court : "I am [...] deeply religious and came to this clique of conspirators out of my religious views ". The sermons of the Münster bishop, Clemens August Graf von Galen, directed against euthanasia were also well known .

For similar reasons, a number of Protestant pastors were arrested and some were sent to concentration camps. Incidentally, the church in the old Prussian church province of Westphalia was also affected by the church struggle between German Christians and the Confessing Church . While at the beginning the German Christians, who were close to the regime, mostly won the presbyter and synod elections , in Westphalia in 1934, President Karl Koch, a resolute opponent of this movement, was elected head of the church province.

The resistance of members of the socialist and communist workers' movement was clearly politically motivated. Dortmund was the center of a communist resistance that continued to form despite arrests. Even at the beginning of 1945 the Gestapo arrested 28 communists who were executed together with 280 other prisoners and prisoners of war in March / April in the Dortmund Bittermark . The supporters of the SPD were mostly less offensive, their main concern was to maintain old contacts and exchange information. Because of their fragmented organization, these groups around Fritz Henßler could hardly be tracked down by the secret police. Only gradually, sometimes not until 1937, was this also smashed.

In Dortmund and other larger Westphalian cities, there were also groups of the edelweiss pirates , informal youth groups with inappropriate and sometimes resistant behavior.

Persecution of the Jews and euthanasia

In the November pogroms during and after November 9, 1938, synagogues were also pillaged in the provinces and, in some cases , as in Lünen , Jewish citizens were also murdered. The processes in Medebach are well documented . As in the rest of the empire, the Jewish community in Westphalia was almost completely destroyed. In 1933 there were about 4,000 Jews in Dortmund, 44 of whom fell victim to the various persecution measures of the regime by 1939. There were also natural deaths. Over 1,000 died in the concentration camps between 1940 and 1945, and another 200 died from exhaustion in the first few months after the war. Some managed to flee abroad by 1941. In the whole of Westphalia, the number of the Jewish population fell from around 18,000 in 1933 to a little more than 7,000 in 1939. This number fell again to 5800 (1941) by the beginning of the systematic deportations to the extermination camps. The Oberpräsident Alfred Meyer was also involved in the Wannsee Conference in his capacity as State Secretary in the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories . In Westphalia, the deportations began on December 10, 1941 with transports from the Münsterland, followed a few days later by Bielefeld and the administrative district of Arnsberg. By the end of March 1943 there were only about 800 Jews left in all of Westphalia. They were likely to have been protected persons in the context of mixed marriages and so-called valid Jews . Few of them returned to the region after the war. They included Hans Frankenthal from Schmallenberg , who later reported on his experiences, and the family of Paul Spiegel, who died in 2006 (until his death chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany) from Warendorf .

The number of killings as part of the so-called euthanasia program was particularly high in the healing and care facilities that were directly subordinate to the province . Most of the adult patients affected by this were murdered outside the province, mostly in the Brandenburg prison . The killing of mentally disabled children also took place in Niedermarsberg in the Sauerland in the local provincial institution . About 3000 Westphalian patients were affected, of which about 1350 were demonstrably killed in Hadamar . Including the later victims, a total of around 3,000 patients can be assumed to have been killed. However , with a few exceptions, the Bethel Asylums succeeded in preventing their patients from being killed until the end of the war.

Second World War in Westphalia

Apart from the transition to a war economy and the introduction of ration cards, the use of prisoners of war and slave labor in agriculture, factories and mines was a first sign that the war had also reached the province. The largest POW camps were the Stalag 326-VI-K near Stukenbrock (Senne) and the Stalag 326-VI-A in Hemer . There were also other camps throughout the province. According to some information, more than 65,000 mostly Soviet soldiers died in Stukenbrock alone. There are similar estimates for Hemer, although the officially recorded death rates are significantly lower.

With the Allied air raids, the war reached the civilian population directly ( air raids on the Ruhr area ). Münster experienced its first air raid in 1940 and the city was the target of heavy night raids even before the start of extensive bombing in 1941. In total, over a thousand people died in the city as a result of air strikes. In Bochum alone there were over 4000 deaths and only 35% of the building stock from 1939 was undamaged in 1945. It was very similar in other cities, not only in the Ruhr area and the big cities, but also on the periphery. The cities of Soest and Meschede, for example, were largely destroyed, but small rural communities such as Fredeburg also suffered massive devastation from Allied air raids. In May 1943, British planes destroyed the Möhnestausees dam . Thousands perished in the floods of Möhne and Ruhr. In Neheim, this mainly affected prisoners of war from a local forced labor camp.

Towards the end of March 1945, the land war reached the land between the Rhine and Weser. In the battle for the so-called Ruhr basin , there were again fierce and costly battles between German and Allied troops. In the forest area around Winterberg, Medebach and Schmallenberg there was heavy infantry fighting at Easter 1945. The resistance was in vain, however, and on April 1st, American troops reached Paderborn and met the units advancing from the north. Shortly before the end of the war, there were various end- phase crimes . These include the massacre in the Arnsberg Forest near Warstein and Eversberg. It was not until April 18, 1945 that the last units of the Wehrmacht surrendered in Westphalia, thus ending the Second World War in this area.

The end of the province

The territory of the province of Westphalia belonged to the British zone of occupation after the Second World War . The border to Hesse was also the border between the British and American zones . The French zone bordered the Westphalian districts of Siegen and Olpe . Until the move to Berlin, Bad Oeynhausen was the seat of the British military government . This largely made use of the German administrative structures. In July 1945 they appointed Rudolf Amelunxen as the new high president for the province. In a similar way, new regional presidents were appointed for Arnsberg ( Fritz Fries ), Minden and Münster. At the beginning of 1946, a new political representative body - the Provincial Council - was set up. Its members came according to a fixed key from the parties that were newly founded or re-established. The SPD provided 35, the CDU 30, the KPD 20, the Zentrum 10 and the FDP 5 members.

The end of the province was sealed with the dissolution of the Prussian provinces in the British occupation zone and the establishment of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia on August 23, 1946 (by resolution of the British cabinet in June 1946). In 1947 the state of Lippe lost its independence when it joined North Rhine-Westphalia and the enlarged district of Detmold was formed from the former administrative district of Minden . Even before the well-known Control Council Act No. 46 on the dissolution of the State of Prussia of February 25, 1947, the province had long since disappeared from the political scene. With the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany and the validity of the Basic Law on May 23, 1949, North Rhine-Westphalia became a federal state in which Westphalia continued to exist as a part of the state.

Upper President of the Province of Westphalia

The Prussian government appointed senior presidents who represented the government in the province and supervised the execution of Central Prussian tasks. From 1920 to 1933, the appointment of a senior president required the approval of the provincial parliament.

| Term of office | Surname |

|---|---|

| 1816 to 1844 | Ludwig von Vincke |

| 1845 to 1846 | Eduard von Schaper |

| 1846 to 1850 | Eduard von Flottwell |

| 1850 to 1871 | Franz von Duesberg |

| 1871 to 1882 | Friedrich von Kühlwetter |

| 1883 to 1889 | Robert Eduard von Hagemeister |

| 1889 to 1899 | Conrad von Studt |

| 1899 to 1911 | Eberhard von der Recke von der Horst |

| 1911 to 1919 | Karl Prince of Ratibor and Corvey |

| 1919 | Felix von Merveldt , DNVP |

| 1919 to 1922 | Bernhard Wuermeling , center |

| 1922 | Felix von Merveldt , DNVP |

| 1922 to 1933 | Johannes Gronowski , center |

| 1933 to 1938 | Ferdinand von Lüninck , DNVP |

| 1938 to 1945 | Alfred Meyer , NSDAP |

| 1945 to 1946 | Rudolf Amelunxen , center |

Governors of Westphalia

At the top of the self-government of the province, the 1,886 newly formed provincial association , the corporation of all counties and cities in the province, elected by the county council was governor (until 1889 officially Country Director), who as provincial government to the provincial committee (Government) headed. From 1933 the governors were subject to the instructions of the upper president; Kolbow was still elected, his successors only appointed, because the provincial parliament had been dissolved since 1934.

| Term of office | Surname |

|---|---|

| 1886 to 1900 |

August Overweg , until 1889 as regional director |

| 1900 to 1905 | Ludwig Holle |

| 1905 to 1919 | Wilhelm Hammerschmidt |

| 1920 to 1933 | Franz Dieckmann , center |

| 1933 to 1944 | Karl-Friedrich Kolbow , NSDAP |

| 1944 provisional | Theodor Fründt , NSDAP |

| 1944 to 1945 | Hans von Helms , NSDAP |

| 1945 to 1954 | Bernhard Salzmann |

See also

literature

- Hans-Joachim Behr : Rhineland, Westphalia and Prussia in their mutual relationship 1815-1945. In: Westfälische Zeitschrift 133/1983, p. 37ff.

- Ralf Blank : The end of the war and the “home front” in Westphalia. In: Westfälische Forschungen 55 (2005), pp. 361-421.

- Detlef Briesen u. a .: Social and economic history of Rhineland and Westphalia . Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-17-013320-9 .

- Gustav Engel : Political history of Westphalia . Cologne 1968.

- Harm Klueting : History of Westphalia. The land between the Rhine and Weser from the 8th to the 20th century . Paderborn 1998, ISBN 3-89710-050-9 .

- Friedrich Keinemann: Westphalia in the Age of Restoration and the July Revolution 1815–1833. Sources on the development of the economy, the material situation of the population and the appearance of the popular mood . Münster 1987.

- Wilhelm Kohl : Small Westphalian History . Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-491-34231-7 .

- Wilhelm Kohl (ed.): Westphalian history . Vol. 2: The 19th and 20th centuries. Politics and culture. Düsseldorf 1983, ISBN 3-590-34212-9 .

In it u. a .: Hans-Joachim Behr: The Province of Westphalia and the Land of Lippe 1813-1933. P. 45–165, Alfred Hartlieb von Wallthor: The landscape self-administration. P. 165–210, Bernd Hey: The National Socialist Era. P. 211–268, Karl Teppe: Between the occupation regime and political reorganization. Pp. 269-341. - Georg Mölich, Veit Veltzke, Bernd Walter: Rhineland, Westphalia and Prussia - a relationship story . Aschendorff-Verlag, Münster 2011, ISBN 978-3-402-12793-3 .

- North Rhine-Westphalia. State history in the lexicon . Red. Anselm Faust u. a. Düsseldorf 1993, ISBN 3-491-34230-9 .

- Armin Nolzen : The Westphalian NSDAP in the “Third Reich”. In: Westfälische Forschungen 55 (2005), pp. 423–469.

-

Wilfried Reinighaus , Horst Conrad (ed.): For freedom and law. Westphalia and Lippe in the revolution of 1848/49 . Münster 1999, ISBN 3-402-05382-9

Darin u. a .: Horst Conrad: Westphalia in Vormärz, pp. 5–13, Wilfried Reininghaus: Social and economic-historical aspects of the Vormärz in Westphalia and Lippe, pp. 14–21, Ders., Axel Eilts: Fifteen Revolution Months. The Province of Westphalia from March 1848 to May 1849, pp. 32–73. - Wilhelm Ribhegge: Prussia in the West. Struggle for parliamentarism in Rhineland and Westphalia . Münster, 2008 (special edition for the state center for political education in North Rhine-Westphalia)

- Karl Teppe, Michael Epkenhans : Westphalia and Prussia. Integration and regionalism . Paderborn 1991, ISBN 3-506-79575-9 .

In it u. a .: Michael Epkenhans: Westphalian bourgeoisie, the Prussian constitutional question and the idea of the nation state 1830–1871. - Alfred Hartlieb von Wallthor : The incorporation of Westphalia into the Prussian state. In: Peter Baumgart (ed.): Expansion and integration. To incorporate newly acquired territories into the Prussian state. Cologne 1984, p. 227ff.

- 200 years of Westphalia - now! Catalog for the exhibition of the city of Dortmund, the regional association Westphalia-Lippe and the Westphalian Heimatbund. Münster 2015.

- Church regulations for the Protestant communities in the Province of Westphalia and the Rhine Province. Bädeker, Koblenz 1835 ( digitized version )

Web links

- Prussian Province of Westphalia on the Internet portal "Westphalian History"

- Topographical-military atlas of the Royal Prussian Province of Westphalia, with its latest division into administrative districts and district councils in 13 sheets

- Topographic map of the Rhine Province and the Province of Westphalia based on the v. Dechen'schen geological map and the Königl (ichen) general staff map (...) in 34 sheets

- Province of Westphalia in GenWiki

- Counties and municipalities 1910

- Province of Westphalia on HGIS Germany

- Prussian Museum NRW

- Westfalenhöfe - Historical data on farms and houses in Westphalia

References and comments

- ↑ a b c Statistical Yearbook for the German Reich 1939/40 (digitized version)

- ^ Jacob Venedey: Prussia and Prussia. Mannheim 1839, p. 202, cit. to Conrad: Westphalia in March. P. 5.

- ↑ cf. on the question of transfer, for example: Keinemann: Westphalia in the Age of Restoration. Pp. 59-68.

- ↑ cit. after: Michael Epkenhans: Westphalian bourgeoisie, Prussian constitutional question and national state idea 1830–1871. In: Teppe / Epkenhans: Westphalia and Prussia. P. 126.

- ↑ about the early years of the province: Karl Teppe, Michael Epkenhans: Westphalia and Prussia. Integration and regionalism. Paderborn 1991, ISBN 3-506-79575-9 .

- ↑ Epkenhans, p. 129.

- ↑ Johann Friedrich Josef Sommer: Legal time courses. In: New archive for Prussian law and procedures as well as for German private law. Born in 1850.

- ↑ cf. on the subject: Wilfried Reininghaus (Hrsg.): The Revolution 1848/49 in Westphalia and Lippe. Munster 1999.

- ↑ Epkenhans, p. 130.

- ↑ cf. on the 1848/49 revolution and on the Vormärz: Wilfried Reinighaus, Horst Conrad (ed.): For freedom and law. Westphalia and Lippe in the revolution of 1848/49. Münster 1999, ISBN 3-402-05382-9 .

- ^ A contemporary report: Johann Nepomuk Schwerz : Description of Agriculture in Westphalia. First edition 1836 (facsimile Münster, no year), cf. for further development: Michael Kosidis: Market integration and development of Westphalian agriculture 1780–1880: market-oriented economic development of a peasant structured agricultural sector. Munster 1996.

- ↑ cf. on the crisis in the linen trade: Keinemann: Westphalia in the Age of Restoration. P. 68ff.

-

^ North Rhine-Westphalia.

Regional history in the lexicon, p. 46 - ↑ compare: The public health system in the government district of Arnsberg: general report. A total of 4 issues appeared. Arnsberg 1888-1894.

- ↑ on social and economic history in the 19th and 20th centuries, see for example: Detlef Briesen u. a .: Social and economic history of Rhineland and Westphalia . Cologne 1995, ISBN 3-17-013320-9 .

- ↑ see: Rainer Feldbrügge: The Westphalian Center 1918–1933: political culture in the Catholic milieu. Dissertation Uni Bielefeld, 1994.

- ↑ cf. on the social democratization of the Ruhr area v. a. after the Second World War: Karl Rohe: From the social democratic poor house to the SPD wagon castle. Political structural change after the Second World War. In: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 4/1987, pp. 508-534.

- ↑ cf. for various aspects of the war the anthology: On the "home front" Westphalia and Lippe in the First World War. Münster, 2014

- ↑ Centralvolksblatt 171/1914 of July 28.

- ↑ Christian Geinitz / Uta Hinz: The August experience in South Baden: Ambivalent reactions of the German public to the beginning of the war in 1914. In: Gerhard Hirschfeld, Gerd Krumeich, Dieter Langewiesche, Hans-Peter Ullmann (ed.): War experiences. Studies on the social and mental history of the First World War. Klartext Verlag, Essen 1997, pp. 20f., 24f., Jürgen Schulte-Hobein: Enthusiasm or skepticism about war? Reactions to the beginning of the First World War in Westphalia. In: On the "home front" of Westphalia and Lippe in the First World War. Münster 2014, pp. 28–32.

- ↑ cf. for example Anne Roerkohl: Hunger Blockade and Home Front. The communal food supply in Westphalia during the First World War. Stuttgart, 1991

- ↑ cf. Wilfried Reininghaus: The revolution 1918/19 in Westphalia and Lippe as a research problem. Münster 2016.

- ↑ Figures taken from the Westphalia article (original version, see discussion page), data could not yet be verified!

- ↑ Peter Menzel: Deutsche Notmünzen ... (1982) p. 484: "Medaillencharakter"

- ^ Numbers from: Klaus Wisotzky: National Socialist German Workers' Party. In North Rhine-Westphalia. Regional history in the Lexicon, p. 307.

- ↑ The district of Iserlohn and the city of Lüdenscheide represent Protestant Westphalia and the districts of Meschede and Olpe represent Catholic Westphalia. Source: Statistics of the German Empire

- ↑ on this, for example: Wilfried Reininghaus: Forced Labor and Forced Laborers in Westphalia 1939–1945. Sources from the Münster State Archives . In: Der Archivar 53/2000, pp. 114–121.

- ↑ cf. on the end of the war: Ralf Blank: End of the war and home front in Westphalia. In: Westfälische Forschungen 55/2005 pp. 361–421

- ↑ Ordinance No. 46 - Dissolution of the provinces of the former Land of Prussia in the British Zone and their new formation as independent countries.