Carl Severing

Carl Wilhelm Severing (born June 1, 1875 in Herford , † July 23, 1952 in Bielefeld ) was a social democratic politician .

He was considered a representative of the right wing of the party. For decades he played a leading role in the party district of East Westphalia and Lippe . Severing acted as a member of the Reichstag during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic . He first played a nationally important role in 1919/20 as Reich and State Commissioner in the Ruhr area .

From 1920 to 1926, as Minister of the Interior in the Free State of Prussia , he decisively advanced the democratization policy of the administration and the police. In Hermann Müller's second cabinet, Severing held the office of Minister of the Interior from 1928 to 1930 . In the final phase of the republic he was again the Prussian interior minister from 1930 to 1932.

During the time of National Socialism he lived as a pensioner in Bielefeld. After the end of the war, Severing became politically active again. Among other things, he was chairman of the SPD in East Westphalia-Lippe and state politician in North Rhine-Westphalia .

Life and work in the time of the empire

Origin and first political experiences

Severing came from a working class family from Herford who lived in cramped conditions. His father Bernhard worked as a cigar sorter, his mother Johanna was a seamstress. The family was Protestant. She got into trouble when her father became mentally ill. Carl and a half-brother had to help the mother sort the cigars, a job that was done at home . A pastor offered to organize funding for attending a high school. He suggested that Carl should later become a pastor himself. Carl refused this offer, however, because he wanted to become a musician. However, this turned out to be unaffordable. After attending primary school , Severing began an apprenticeship as a locksmith , which he completed in 1892.

Politics played no role in the family, but Carl showed an early interest in the socialist labor movement. A colleague introduced him to her goals. Immediately after his journeyman examination, Severing joined the free trade union German Metalworkers' Association (DMV). He soon took up first positions within the organization. He was secretary and was elected to the local union cartel as a representative of the DMV in 1893 . In the same year Severing stood up for the establishment of a social democratic local association in Herford. This establishment did not last long, however, and Severing felt compelled to make a second attempt in 1894 together with a few others. At that time Severing was already working as a correspondent and contact person for the social democratic newspaper Volkswacht from neighboring Bielefeld. He got to know Carl Hoffmann and Carl Schreck, the then leading Social Democrats in Bielefeld, with whom he later had a special relationship of trust and work.

As reasons for his involvement in the labor movement, he later stated: “The motives that determined me to join the trade union, to join the social democratic party (...) were more from feeling, from the will to freedom and economic advancement than input from scientific knowledge. "

In 1894 Severing left Herford and moved to Bielefeld. There he gave up his craft and switched to industry. He found a job with the Dürkopp plants . In Bielefeld, too, he was involved in the party and trade union. In 1896 he played a leading role in a failed strike or lockout at Dürkopp. Because of this, he lost his job.

The years in Switzerland

After losing his job, Severing migrated south and came to Zurich in 1895 after various stations . There he worked as a skilled worker in a metal goods factory and was involved in the Swiss Metalworkers' Association , which had its own sub-organizations for immigrant German workers. He also found a connection to the "Local Committee of German Social Democrats" and the German workers' education association "Eintracht." Severing quickly established himself as a leading figure in the various associations. In the Swiss years, Severing's political views became much more radical. His criticism of the politics of social democracy led to his resigning from his functions in the workers' education association. In his speeches he often spoke of the “ world revolution ” and no longer only of the improvement of the political and social situation of the workers. From a distance he observed critically that a decidedly pragmatic course prevailed in the SPD in East Westphalia and that they even considered participating in the Prussian state elections, which were frowned upon because of the three-class suffrage. In 1898 he left Switzerland and returned to Bielefeld.

Rise in the Bielefeld labor movement

After returning from Switzerland, Severing married a distant relative (Emma Wilhelmine Twelker) who was expecting a child from him. The marriage had two children. The relationship of the spouses to one another corresponded to the rather petty-bourgeois-patriarchal behavior of the time. As a housewife, the woman remained completely dependent on the family. Severing's traditional understanding of the role of man and woman was evident, for example, when his daughter started studying: Although he allowed her to study medicine, he said she would give up and get married after a few semesters anyway.

Immediately after his return, he became involved again in the regional labor movement. In 1899 he gave his first lecture to the Bielefeld Social Democrats that dealt with the inadequate primary education. In contrast, he propagated self-education and support from organizations oriented towards social democracy. Lively educational events would also be more attractive than dry political lectures. With his then radical views, he remained largely isolated within the party. He did not succeed in persuading the East Westphalia district to condemn the " revisionists " around Eduard Bernstein .

Due to the lack of support in the party, the focus of Severing's work shifted to trade union work. In this area he rose quickly and in 1901 became managing director of the local branch of the German Metalworkers' Association . At that time the local union had only about 1,300 members, which corresponded to a degree of organization of about 30%. During Severing's tenure, the number of members increased sixfold, which was significantly higher than the increase at the national level. In 1906 the degree of organization was already 75%. The introduction of a shop steward system contributed to its success. This system guaranteed proximity to the concerns and needs of the members. Severing's closeness to the grass roots was one reason for his popularity with the Bielefeld workers. Even then, he went unfamiliar ways with his agitation measures. An orchestral concert that he organized for the tenth anniversary and attracted 2,000 visitors proved to be effective in advertising.

Starting from his base in the metalworking movement, Severing extended his sphere of influence to the entire trade union organization in Bielefeld against fierce resistance from other associations. By 1906 at the latest, he was the central figure in the city's labor movement. In 1906 and 1910 Severing achieved success for the workers without a strike. It was not until 1911 that there was a major work stoppage, which was also successful. In 1912 he gave up his post in the DMV.

In the years of predominantly trade union activity Severing's political view changed significantly. Revolutionary positions were replaced by a pronounced pragmatism, which within the party was often considered "right". His goal was no longer the “dictatorship of the proletariat”, but the integration of the workers into society. In this respect, he moved closer to the revisionist positions that were once fought against.

Severing's position on cultural issues was typical of the working class movement in the German Empire. On the one hand, the bourgeois culture was criticized, on the other hand, it was ultimately oriented towards it. For Severing, the formation of German culture was essentially completed with classical music . Gotthold Ephraim Lessing would have shaped the "reconstruction" of the dome, while Johann Wolfgang von Goethe arched the "dome" over it. Severing himself wrote poetry throughout his life. They were printed in the People's Watch and, after the Second World War, in the "Free Press". In 1905, men and women from the trade union and social democratic environment formed the “Freie Volksbühne Bielefeld” theater audience under his leadership. It was the second organization of its kind in Germany. With their membership, the workers acquired a subscription that enabled them to attend theater or concert performances at low cost. Severing remained connected to this organization and was one of the re-founders of the Volksbühne in 1947 as a “man from the very beginning”.

Politics since 1903

Severing's influence on the Bielefeld labor movement was based primarily on his trade union success during the German Empire. Through the “union of the party” ( Karl Ditt ), his indirect influence on the party through close co-workers was large enough to be able to do without even leading positions in it.

The general parliamentary voice was more important to him. He ran for a seat in the Reichstag for the first time in 1903 , this time in a hopeless position, even if there was a strong increase in social democratic votes. Severing was a city councilor in Bielefeld from 1905 to 1924 . The third department of the city council has since been dominated by the Social Democrats. Severing quickly took on leadership roles within the parliamentary group. The previously rather quiet gathering of dignitaries has since become much more political, as Severing openly addressed the grievances in the city. Severing's role was well appreciated by the bourgeois press: “He is perhaps the most interesting figure in Bielefeld's social democracy. Extremely hard-working, extremely well-read, he put the stamp of the individual on the metalworkers' association. As a speaker, he combines sharpness with enthusiasm. The masses follow the man. "

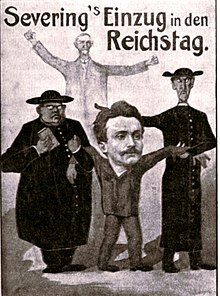

In the Reichstag election of 1907 , he was elected to the Reichstag for the first time in the constituency of Minden 3 (Bielefeld - Wiedenbrück) in a runoff vote with the help of the votes of the center voters with a 2,000-vote lead over the national liberal candidate, the Minister of State Theodor von Möller . Its success contrasted with the Reich trend: the Social Democrats lost across the Reich in these so-called " Hottentot elections ", branded as "Reich enemies", significantly in voters and mandates.

With this victory not only the reputation of the Bielefeld Social Democrats in the party as a whole increased considerably, Severing himself also moved up into the inner circle of decision-makers. He was the youngest member of the Reichstag parliamentary group. In view of his union past and his now reformist attitude, he joined parliamentarians who also came from the trade union movement. These included Carl Legien and Otto Hue , and later he was in contact with social democrats who had a bourgeois background, such as Eduard David , Wolfgang Heine and especially Ludwig Frank . Within the group, Severing developed into a sought-after speaker in plenary sessions and a knowledgeable member of numerous committees. One focus of his work was on social policy . It was during this time that regular publications began in the revisionists' theoretical organ, the Socialist Monthly . In addition, he wrote regularly for the Bielefeld People's Guard about his activities in Berlin and about his participation in international metalworkers' congresses in Brussels (1907) and Birmingham (1907). Severing also took part in the International Workers and Socialists Congress (1910) and the International Socialists Congress in Stuttgart (1907).

Severing became known to the general public when he made irregularities in the imperial shipyards in Kiel and Danzig public in a Reichstag speech in 1910 and described a contrary report in a naval newspaper as lying. After tumultuous scenes, he responded to a call to order from the President of the Reichstag with the words: "Mr. President, I mean, a rat is a rat and a liar is a liar."

The election campaign of 1912 was the harshest and most polemical in the Bielefeld-Wiedenbrück constituency to date. All sides viewed it as a matter of prestige. Severing's opponent was Arthur von Posadowsky-Wehner . This conservative had largely determined the domestic and social policy of the empire until 1907 and stood as a joint candidate of the center , national liberals and conservatives . While both candidates were tied in the first ballot, Posadowsky won the runoff because the base of the left-liberal Progress Party did not vote for Severing, contrary to the vote of its party leadership.

The loss of the Reichstag mandate did not mean that Severing lost his influence in the party. Rather, he remained one of the most influential "provincial princes" and played an important role in the so-called "party committee", a body that, in addition to the board and parliamentary group, was supposed to represent the influence of the districts on the party as a whole.

Severing also gave up his position at DMV in 1912. Behind the scenes he still acted as a strong man in the Bielefeld trade union movement, but at the same time he was looking for new tasks beyond the trade union detail. From 1912 to 1919 he was editor and de facto head of the social democratic people's watch in Bielefeld.

First World War

War advocates

Shortly before the start of the First World War , a large anti-war demonstration took place in Bielefeld. Even there, Severing cautiously spoke out in favor of social democratic support for a conflict that was interpreted as a defensive war. On August 1, 1914, it became clearer: "If the die is cast, then there is only one goal for social democracy: to protect the German people by all means against the power-hungry claims of the 'peace tsar'." On August he wrote “Inter arma silent leges! (...) The war is here and we have to fight back. ”To legitimize the approval of the war credits, Severing resorted to statements by Ferdinand Lassalle and August Bebel . That he, like Ludwig Frank, saw war policy as a means of enforcing social equality for workers and long overdue reforms, is likely because of his closeness to Frank and Wilhelm Keil .

He remained on the line of the war advocates in the following years and attacked the war opponent Karl Liebknecht in 1916 with partly false and polemical accusations. In 1915, Severing even denied Hugo Haase the right to express his critical stance in the party committee .

Severing succeeded in swearing the SPD Bielefeld-Wiedenbrück on the course of the party majority around Friedrich Ebert , supported by the regional social democratic press . When the party majority was about to split up from the critics in January 1917, Severing was one of the most resolute advocates of a clear cut: “All these well-intentioned speeches for two years do not change the fact that we will break up if we don't hold together the last bits today . "

While the new USPD played an important and sometimes dominant role in other parts of the Rhineland and Westphalia , it was barely able to gain a foothold in East Westphalia.

Truce policy

The castle peace policy of the Bielefeld SPD meant that the party's supporters were recognized at the local level. Severing himself became a deputy of the school commission. Even more important was that Severing was included in an informal discussion group of Bielefeld dignitaries around Albert Bozi, in which important problems were discussed in advance of local political decisions, but also concepts for the post-war period were developed. Together with the social democratic lawyer Hugo Heinemann , Bozi published a work entitled: “Law, Administration and Politics in the New Germany”, in which articles by Severing also appeared. During the revolution of 1918, a “sociopolitical working group” of employers and employees emerged from this group. This body was concerned with preventing conflicts without strikes as early as possible. Severing's attempt to transfer this Bielefeld example to other cities was unsuccessful, however.

During the war, Severing became an equal part of the Bielefeld establishment, which had hitherto been exclusively bourgeois. Together with commoners he called for the subscription of war bonds in 1917 .

Suffrage campaign, peace resolution and end of the war

While the truce policy was overall successful for Severing at the municipal level, it only slowly brought about changes in favor of the workers at the national level. This applies, for example, to the abolition of the three-tier voting system in Prussia. After Wilhelm II's Easter message of April 1917, the SPD parliamentary group passed a resolution in the Bielefeld city council that advocated change. In addition, the workers were called to a mass meeting, at which Severing spoke.

In spite of the general approval of the truce, Severing and other Bielefeld Social Democrats repeatedly criticized war profiteers , “pushers” and the inability of the authorities to combat the growing need of the population at large popular assemblies . Severing saw the government's intervention in the free market as "war socialism". He asked to continue on this path. "Not less, but more socialism must be the slogan of the future."

Although shortly beforehand he had called for the subscription of war bonds, Severing welcomed the peace resolution of 1917. He also saw it as a step towards a democratic system and cooperation with other parties. He summed up at an extraordinary district conference of the SPD: "We came out of the tower, that was the great importance of the day."

When a dictated peace with the new Bolshevik Russia was concluded in Brest-Litovsk , which stood in clear contrast to the peace of understanding called for in the peace resolution, Severing organized large demonstrations in Bielefeld. As in other parts of the Reich, politically motivated strikes broke out in Bielefeld in January 1918. Here, too, the SPD was at the forefront of the movement in order to steer it in a moderate direction. The work stoppages ended after just two days. Friedrich Ebert described Severing's approach as a model for the entire empire.

In the last days and weeks before the revolution, Severing behaved very contradictingly. On October 17, 1918, he again publicly called for the subscription of war bonds, but on October 27, he spoke quite differently. “My opportunistic policies have often been referred to as 'braking,' but I would consider that policy to be entirely compatible if I opposed anything an unlawful power would order an irresponsible military camarilla. I would put myself at the head of a movement that organized open outrage against a military war. 'Bend or break' would then be the watchword. ”The speech corresponded to the reorientation of the policy of the Social Democrats, which a few days later demanded the emperor's resignation.

November Revolution

Not least because of the close involvement of the SPD in local politics, the November Revolution went off without a hitch, and Bielefeld was considered the quietest industrial city in Germany at that time. When Severing found out about the beginning of the revolution on November 8th, he was determined to keep the reins of action in hand. Significantly, in Bielefeld there was no workers' and soldiers' council , but a people's and soldiers' council. Even if the SPD and the trade unions were behind it, this made clear the opening towards other social groups. When armed foreign sailors tried to storm the prison that same day, Severing managed to calm the crowd.

Negotiations with the authorities took place a day later. The program of the People's and Soldiers' Council conceived by Severing aimed solely at maintaining public order and ensuring supplies; political claims were not associated with it. On November 17th, the People's and Soldiers' Council elected an executive committee, one third each of which consisted of workers, employees and representatives of the bourgeoisie. Severing acted from the important position of the person responsible for the security service and, together with a trade unionist, held the overall chairmanship. He was the decisive person for the further development of the council. The Bielefeld council organization became the coordinating body for all of East Westphalia and Lippe. The majority followed Severing's moderate course. He was elected as a delegate to the First Reich Congress of Workers 'and Soldiers' Councils in Berlin. There he was one of the three chairmen of the MSPD faction. Although he supported Ebert's policy in principle, Severing, together with Hermann Lüdemann, submitted the application for the socialization of all mature industries and thus acted against Ebert's intentions. Nevertheless, Severing contributed to a large extent to the fact that the line of the majority Social Democrats was able to prevail overall.

The renowned Vossische Zeitung was impressed by how Severing dealt with the delegates, among them "dozens of wild men, soldiers with war-torn nerves, foam at the mouth, babbling with excitement". "In the midst of this fermentation, this storm and turmoil, defenseless among the violent: a small, inconspicuous, silent man, with the hands of a worker, the forehead of a scholar, the eyes of a believer: Carl Severing, at that time still an unknown worker leader from Bielefeld, but the representative of four decades of trade union discipline, responsibility, sobriety and community spirit. "

Weimar Republic

Parliamentary activity at the beginning of the republic

Severing was a member of the Weimar National Assembly in 1919/20 . Then he was again a member of the Reichstag until 1933 . He was also a member of the Prussian state parliament from 1919 to 1933 .

In the formation of the Weimar coalition, Severing played an important role as a proponent of an alliance of MSPD, bourgeois democrats and the center as one of the negotiators of the MSPD together with Paul Löbe . It was thanks in particular to Severing's negotiating skills that the Center Party also took part in the coalition government.

In the German National Assembly, he advocated the adoption of the Versailles Treaty because he was of the opinion that the sacrifices that could be made in the event of a rejection could not be justified.

Reich and State Commissioner in the Ruhr area

In the Ruhr area, the trade unions and the MSPD had lost considerable influence in favor of the USPD and the KPD . The socialization movement that spread there at the beginning of 1919 , in which all workers' parties were involved, pursued the goal of socializing the mining industry. In the course of the strike, a syndicalist association was formed with the General Miners Union .

As Reich and State Commissioner Severing was given the task of easing the situation. The Reich as well as the Prussian government combined the intention of adding a politician to the commander of the General Command in Munster, General Oskar von Watter , who should minimize the use of force as much as possible. In his appeal on April 8, Severing announced that he wanted to “speak to the workers as a workers representative and act as workers for the workers.” The decisions he made were not primarily aimed at violent repression, but were an attempt to reach an understanding with the striking workers and the removal of existing hardships and grievances. Violence should only be used where it is provoked. He was able to settle the strike quickly using both repression and negotiation. An order provided for the compulsory obligation of all able-bodied men to do emergency work. He also had the "ringleaders" of the strike arrested. On the other hand, those willing to work received special rations. Negotiations allowed the miners to work the seven-hour shift and the strike front began to collapse.

Even when the actual task was completed, Severing remained in office. He should contribute to the permanent calming of the situation in the area. In particular, he tried to improve the supply situation. The Prussian government now valued him as a crisis manager. She temporarily sent him to Upper Silesia . In addition, its competencies have been expanded beyond the narrow Ruhr area to other neighboring regions. With the support of Ernst Mehlich and Fritz Husemann , Severing settled numerous conflicts between employers and employees.

Although he also campaigned for the Bielefeld workers, Severing temporarily lost control of all things on his home ground. When riots broke out there in June 1919, he had to flee and was forced to impose a state of siege on the city. These measures in particular led to conflicts with the Bielefeld SPD.

From the beginning there were also disputes over competence with the military, especially with General von Watter. In order to be able to better control the partially unauthorized procedure, Severing relocated his office from Dortmund to Münster.

The situation in the district remained essentially calm until the beginning of 1920. When it intensified again through a railroad strike and miners' strike, Severing took repressive measures against it. This included the dismissal of striking railway workers. He took similar action against the attempt by the syndicalists to force six-hour shifts in the mining industry. He also pushed through overlaying against the coal crisis in the empire. In return, he campaigned for better care and pay.

The majority Social Democrats explicitly recognized Severing's efforts to normalize the situation in the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area at the party congress of 1919. It played a role that Severing - unlike Gustav Noske - knew how to assert himself against the military.

Kapp-Putsch 1920 and Ruhrkampf

The first really serious threat to the republic came from the political right in the Kapp Putsch . There were some among the coup plotters who ultimately unsuccessfully advocated including right-wing social democrats like Severing in the new government. Severing himself was in East Westphalia at the beginning of the coup and organized the resistance there. Together with the Upper President of the Province of Westphalia, Bernhard Wuermeling, he was clearly on the side of the legitimate government. General Watter, however, refused to sign a corresponding appeal and was secretly close to Kapp. In the Ruhr area, the general strike against the Kapp Putsch developed into a general uprising movement directed against Watter and the voluntary corps subordinate to him. At times a Red Ruhr Army was able to prevail against the Freikorps. Only after the defeat of his troops did Watter commit himself to the constitutional government on March 16, 1920.

Severing's call on March 21 to return to work after Kapp's defeat was ignored by the strikers. Not only did the opposition to the Freikorps and Watter play a role, the memories of the coercive measures for which Severing was responsible also exacerbated the situation.

The Red Ruhr Army now ruled the entire Ruhr area and stood before Wesel . There were disagreements between the moderate central leadership in Hagen and the radical forces in the West. At this point in time, the two governments in Berlin did not want to respond to the rebels with the full commitment of the army. Severing had made it clear that the movement could not be ended by military means alone. First, an attempt should be made to find a negotiated solution. For this purpose Severing brokered the so-called Bielefeld Agreement . However, the agreement suffered from various deficits. Neither representatives of the radical councils of the West nor representatives of the Red Ruhr Army were invited. Speakers of the KPD and USPD who pretended to speak for them were not legitimized by anything. On the other hand, the military was insufficiently involved in the agreements and did not feel bound by them. Severing refused to replace General Watter, which was also often called for from the ranks of the SPD, because there was no alternative to him and all officers in his military district had shown solidarity with him. By making concessions to the strikers, the governments in Berlin did not really recognize the agreements either and began to thwart Severing's attempts at pacification.

The agreement was therefore only partially successful. He was able to report a split in the movement as a success. The moderate forces from the environment of the trade unions, the MSPD, the Democrats and the center soon withdrew from the Ruhr Army because it had distanced itself from the original goal of protecting the constitution. In other parts, especially in the west, the fighting continued. Then the Reichswehr and Freikorps marched into the Ruhr area. Severing finally saw no alternative to military intervention either. He even asked the German government to obtain permission from the Allies to march into the demilitarized zone. His concern was no longer to keep the Reichswehr away, but to prevent unnecessary bloodshed. General Watter acted largely without consulting Severing. The latter tightened an ultimatum issued by the government to disarm the Ruhr Army so that the rebels no longer had the opportunity to comply with the requirements. As a result, the Reichswehr and Freikorps marched on the orders of Hans von Seeckt . The entry of the troops was accompanied by the mistreatment and killings of numerous insurgents. Severing now tried to end the "White Terror" as possible. It was not until late that he succeeded in stopping the practice of professional shootings. From this point in time at the latest, it was clear to Severing that the army was unsuitable for maintaining internal order, as its use only increased public displeasure.

Beginning of the Severing system in Prussia

After the Kapp Putsch, there were changes in government in both the Reich and Prussia. Interior Minister Wolfgang Heine was criticized in the Prussian government . He had shown little will to modernize the bureaucracy in the interests of the republic, and had even brought some coup supporters into leading positions. Heine resigned from office immediately after the coup. The new people at the top included Otto Braun as Prime Minister, Hermann Lüdemann as Finance Minister and Severing as Minister of the Interior. The new men did not pursue any more left-wing politics than their predecessors, but differed from them in the greater clarity and energy of their politics. Severing's tasks included controlling the administration and the police. In Prussia, the Minister of the Interior had the most powers alongside the Prime Minister. The central task of Severing was the republicanization of the administration and the police.

Severing was officially appointed on March 29, 1920; but because he was still busy handling his business in the Ruhr area, he did not take part in a Prussian cabinet meeting until mid-April. In the ministry, Severing managed to win over leading officials from the start. This initially included State Secretary Friedrich Freund (DDP) and Friedrich Wilhelm Meister (DVP), later Freund's successor. In particular, the management of the HR department was immediately replaced by Severing. Fritz Mooshake (DVP) and Heinrich Brand (Center Party) took on this task.

Severing's tasks in the early days of his ministerial activity also included the political implementation of the draft for a new Prussian constitution drawn up in particular by Bill Drews and Friedrich Freund . However, the draft came from Heine's tenure; Severing therefore hardly appeared in the drafting of the constitution.

Republicanization of the administration

At the beginning of his measures to republicanize the administration, officials who had joined the putschists or openly sympathized with them were put at the disposal of those officials. Severing's requirement, which he placed on officials, was that they should stand up for democracy out of conviction and not just grudgingly accept it as a given fact. From his point of view, a change had to be made, especially in the area of so-called political officials , from the district administrators to government and senior presidents to high ministerial officials and state secretaries. After the coup, about a hundred senior officials were removed from their posts. They were replaced by staunch Republicans. Severing rejected the eligibility of the district administrators, which was demanded by the political right, knowing about the strength of the DNVP in the district assemblies of the eastern provinces. District elections would have strengthened the position of the right there. By 1926, at the end of Severing's term of office, all but one of the upper presidents, all regional presidents and more than half of all district offices had been appointed by republican governments. The top positions were almost entirely taken by supporters of the coalition parties. In the western provinces this also included many district administrators (78%), in the east the balance was less impressive with a third.

In his personnel policy measures, Severing made sure not only to appoint social democrats, but also democrats from all political camps. The appointment of Gustav Noske as chief president was more his person than the party owed. However, the Social Democrats were clearly over-represented as police presidents. Severing hardly changed the basic structure of the Prussian administration out of respect for its effectiveness. He did not succeed in breaking the legal monopoly. Only a few non-lawyers from outside got into management positions in the administration.

Police reform in 1920

In addition to the democratization of the administration, a reform of the police was the most important factor in the Severing system. In the years after the revolution he came to the conviction that only a powerful police force could prevent the military from being deployed inside in the event of disruptions to public order. Supporters of the Kapp Putsch were also dismissed from the police force and in particular the security police.

The reorganization and expansion of the police depended heavily on the approval of the former war opponents. Against their initial opposition, Severing pushed through the nationalization of the so far partially municipal police and the establishment of police headquarters and directorates. In 1920, in the “Boulogner Note”, the Allies ordered the dissolution of the paramilitary units and the establishment of a police force. Of 150,000 men, 85,000 were to be in Prussia alone. Severing brought Wilhelm Abegg into the ministry to organize the new police force . The protection police were a considerable power factor, but the police officers usually came from the ranks of the old army and internally were mostly far removed from democracy. In this respect, the internal republicanization of the police had clear limits. In order to partially counteract this, Severing attached great importance to the personality development of the police officers and had a number of police schools built.

Prohibition of defense and Central German uprising

With the support of the new police force, Severing was able to begin in 1920 to ban and dissolve the Orgesch , protection forces and similar organizations. Basically, Severing saw in an organization ban only the last resort in the fight against anti-constitutional organizations. As long as these or their members did not turn actively against the republic, he did not intervene. In 1921, he repealed the ordinance that forbade communists from holding offices in state and local government. For him, membership was not enough for exclusion. Severing only intervened when radical groups actually became subversive. This gradual behavior led to criticism from some Social Democrats, who often wanted a harsher approach.

The Central German uprising was put down in Severing's first term as Minister of the Interior . The political background was a Communist offensive strategy formulated by the Comintern , which aimed at putschist actions outside Russia. The immediate cause was the invasion of the newly formed police units in the central German industrial area. In ignorance of the KPD's plans, Severing wanted to restore order in this region that had remained restless since the Kapp Putsch. With the advance of the police he wanted to forestall the invasion of the Reichswehr. The action was also a test for the new police units. It did not trigger the planned coup, but merely brought it forward. There were fights in which the police quickly prevailed, especially since there were no attempts by KPD supporters to join the action except in the Ruhr area and Hamburg. The comparison of damage and casualties between the fighting in the Ruhr area in 1920 and the Central German uprising confirmed Severing's view that the use of the police was preferable to that of the military.

Change of government and new term of office

After only a year people began to talk about the Severing system, a republican Prussia. The state elections of 1921, however, significantly weakened the SPD. A minority government was formed by the center and the DDP under Prime Minister Adam Stegerwald . Alexander Dominicus (DDP) took the place of Severing .

After leaving his ministerial office, Severing initially recovered from the efforts of recent years. He also spoke at a mass meeting in Bielefeld on the occasion of the murder of Matthias Erzberger . Since, in Severing's opinion, his successor began to abandon his domestic political course, he now vehemently pleaded for large coalitions in the Reich and in Prussia. A prerequisite for this was a change in the SPD itself. Before the Görlitz party congress, Severing wrote: “If he [the party congress] wants to meet his duty, then his debates need only be driven by one spirit: the will to power, the courage of the people Responsibility. ”The party congress actually not only led to the adoption of the strongly revisionist and short-lived Görlitz program , but also to a resolution that also enabled government cooperation with the DVP.

In Prussia, efforts then began to replace the Stegerwald minority government with a grand coalition including the SPD and DVP. The chief negotiator was Severing on the side of the Social Democrats. This succeeded in persuading the DDP to leave the previous government. The Stegerwald government resigned on November 1, 1921. Otto Braun became Prime Minister again and Severing became Minister of the Interior. In the opinion of contemporaries like Friedrich Hussong (DNVP), Severing was the real strong man in the government. In order to accommodate the new coalition partner DVP, Severing appointed Wilhelm Meister as State Secretary after the death of Friedrich Freund. There was certainly conflict between the two, but there is no evidence that the Secretary of State thwarted Severing's policies.

In contrast to the first year as minister, when the communists appeared to be the republic's most dangerous enemies, the situation changed, especially after the attacks against Scheidemann and Walter Rathenau. Severing now took up the fight against the right and was in accordance with the corresponding emergency ordinance of Reich Chancellor Wirth. Numerous right-wing organizations were banned in Prussia. Among them was the steel helmet in 1922 . However, this decision was overturned by the State Court for the German Reich . The attempt by Braun and Severing to also take action against illegal Reich defense units essentially failed due to resistance from General von Seeckt. In the face of the political murders, however, Severing succeeded, against the resistance of the center, in exchanging other high-ranking officials, particularly in the province of Westphalia and the Rhine province.

Crisis year 1923

The next big challenge for Severing was the occupation of the Ruhr area by French troops in 1923. Severing was one of the clearest supporters of passive resistance. On the other hand, he was an opponent of an active and violent resistance propagated and carried out by the right-wing groups. The fight against the right also included Severing's ban on the German National Freedom Party on March 22, 1923. As a result, hatred against Severing increased on the right-hand side of the political spectrum. The DNVP even tried to persuade the DVP to leave the coalition with reference to the Interior Minister - an endeavor that ultimately failed. The right also tried to make Severing responsible for the death of Leo Schlageter . In contrast to the accusations from the right and from Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno , Severing did not ignore the extreme left dangers. He made this clear by banning the proletarian hundreds in Prussia. Severing concluded an alliance with the Reichswehr chief Hans von Seeckt against the right-wing "protective formations" . Among other things, this made it easier to build up the Black Reichswehr . The goal of delimiting the Reichswehr from the right wing units could not be achieved. The passive resistance could no longer be sustained in the face of rising inflation. The crisis was overcome under the new Reich government led by Gustav Stresemann , in which the SPD was initially involved at Severing's initiative. The participation of the SPD ended because of the planned limitation of the eight-hour day. A majority of the leading social democratic politicians, particularly Paul Löbe , spoke out in favor of a withdrawal of their ministers under pressure from the trade unions. One of the few who advocated staying in government was Severing. He feared a shift to the right under a government without social democratic participation. He implored his party: “Think about the consequences!” Even if Severing himself had banned extreme parties during the state crisis, after overcoming the acute crisis he and Friedrich Ebert were in favor of the KPD, NSDAP and the German National Freedom Party before the Reichstag elections to be admitted again to the Reichstag elections of 1924. He argued that banning measures would contribute to radicalization.

Minister under Marx and Braun

In Prussia, too, there was finally a change of government. The DVP withdrew its ministers and on February 10, 1925 Wilhelm Marx (Zentrum) was elected as the new Prime Minister. He left Severing in office, hoping to win the SPD for support from the government. Marx failed in his own ranks, also because politicians from the right wing of the Center Party such as Franz von Papen refused to follow the government because of Severing's adherence. The crisis was finally overcome by a new version of the Braun government. Severing was Minister of the Interior in this too.

However, he was tired of office now. His plans for a major administrative reform, including the dissolution of the district governments, failed. He did not make any further progress in the area of democratization of the administration, especially since there were no similar measures at the Reich level. In addition, the personal relationship between Braun and Severing had deteriorated. Braun was of the opinion that Severing would no longer take action hard enough against the enemies of the republic. He used Severing's long illness to take action against right-wing politicians and groups without consulting him. He also made personnel decisions in the Ministry of the Interior without consulting Severing. Another aspect was the constant, sometimes defamatory, attacks by the extreme left and right. In October 1925, the DNVP launched a vote of no confidence in him in the Prussian state parliament. In his plenary lecture, he vigorously defended himself, which even prompted the Neue Zürcher Zeitung to comment with praise. The application failed, but severely weighed on Severing's self-confidence. In addition, Severing was innocently drawn into the affair of a fraudulent businessman. To a certain extent, Severing viewed the International Police Exhibition in Berlin in 1926 as the culmination and conclusion of his term of office . Apart from technical aspects, he wanted to present the successful development of the Prussian police from an organ of the authoritarian state to an institution of the republican state. After a lengthy illness, he officially resigned on October 6, 1926. Albert Grzesinski was his successor .

Way to the Müller cabinet

To restore his health, Severing spent some time on a cure in Baden-Baden after his resignation and also stayed in Italy . During this time he wrote his memories of his time as government commissioner in the Ruhr area. These were a great success under the title “1919/20 in the Wetter- und Watterwinkel” (1927).

In the background, Severing now campaigned for the formation of a grand coalition at the national level. If necessary, he was also prepared to postpone socio-political reform policy in order to win the DVP for cooperation. While leading social democratic politicians like Hermann Müller saw this in a similar way, the party's attitude as a whole was initially rather negative. However, a group around him, Otto Braun and Rudolf Hilferding , succeeded in moving the SPD party congress in Kiel in 1927 to a resolution aimed at conquering positions of power at all political levels.

The 1928 Reichstag election offered the chance to regain influence at the Reich level . During the campaign, the SPD noted in particular rejection of the assembly of the tank vessel A at the center. Severing, who himself did not share this position, gave the keynote address against the new building in the Reichstag. With the slogan "Child feeding instead of armored cruiser" the SPD was successful and was able to grow strongly. Even before Hermann Müller's government was formed, it was clear that Severing would become Minister of the Interior. He himself led the difficult coalition negotiations on the part of the SPD. Attempts to conclude a formal coalition agreement failed, and so initially only a “ government of personalities ” came into being.

Reich Minister of the Interior 1928–1930

The office of the Reich Minister of the Interior had significantly fewer options than the post in Prussia, especially since administration and police were largely a matter for the states. Severing began to reshuffle the head of the ministry in the republican sense. Hans Menzel, as the new head of the constitutional department, began with changes in the Reich bureaucracy in the sense of democratization. Despite the personal disagreements with the Prussian Minister of the Interior Grzesinski, Prussia and the Reich worked together more intensely than ever on domestic politics during the phase of the grand coalition.

Politics up to the crisis around the building of the armored cruiser

From his predecessor Walter von Keudell , Severing had taken over the preparatory work for a comprehensive reform of the Reich to reduce disputes over competencies, to dissolve small states and other measures. Severing himself, who would have loved to let all the countries in the Reich merge, was skeptical about the chances of success of a major Reich reform. Nevertheless, together with Arnold Brecht in Prussia, he tried everything to make the project a success. Ultimately, the imperial reform failed in particular because of resistance from Bavaria and other countries.

Standing v. l. To the right: Hermann Dietrich , Rudolf Hilferding , Julius Curtius , Carl Severing , Theodor von Guérard , Georg Schätzel . Sitting v. l. To the right: Erich Koch-Weser , Hermann Müller , Wilhelm Groener , Rudolf Wissell .

Not pictured: Gustav Stresemann

Like Ernst Heilmann, Severing was one of the few social democrats who had recognized the political importance of radio. For them, the radio should broadcast in the spirit of republic and democracy. He vehemently opposed the privatization of broadcasting. Controversial discussion programs on the radio went back to Severing. In addition, he rebuilt the supervisory bodies in the interests of greater social plurality. All this led to the fact that the political right called Severing a "broadcast dictator". A fundamental broadcasting reform, the preparatory work of which was well advanced, no longer came about because of the end of the Müller government. Another aspect of Severing's media policy was his endeavor to prevent the right-wing Hugenberg group from monopoly in the field of weekly news shows . At his suggestion, the Reich acquired the majority of the last independent newsreel producer.

The Müller government soon raised the question of building new naval ships, which had already played a major role in the election campaign. The bourgeois coalition partners insisted on implementing the plans and threatened the end of the coalition. Severing and the other social democratic ministers wanted to keep the government and agreed. This sparked a wave of resentment in the party. Severing has tried to defend the decision of the government members offensively. But even the majority of the Reichstag parliamentary group could not be convinced. Rather, it forced the members of the government to vote against their own bill. Since these votes did not change the adoption of the law, the coalition remained.

The tough attitude of the entrepreneurs in 1928/1929 led to a conflict with the trade unions in the so-called Ruhreisenstreit and to the lockout of metal workers in the Rhenish-Westphalian industrial area. The business side brought Severing into play as an intermediary through DVP. Severing was recognized by the unions, but they mistrusted special arbitration. Severing accepted the arbitrator role on the condition that both sides declared in advance that they would submit to his arbitrator. In his attempt at arbitration, he was not bound by previous arbitrator rulings. After a violent conflict, Severing was finally accepted by the union camp. His decision led to somewhat lower wages for the employees than in the arbitration ruling of his predecessor. Both sides were not entirely satisfied with it, but rated it as a success for their cause. Sharp criticism came from the left wing of the SPD. The Leipziger Volksstimme even spoke of a "Severing scandal."

Military policy remained on the agenda within the party. At the party congress in 1929 there was a dispute over a "defense program" that had been presented by a commission. The left “class struggle group” around Paul Levi and others spoke out against this . This group categorically opposed the military because they viewed it as a means of suppressing the working class. Severing was one of the main speakers on the present proposal. He warned against “only constantly criticizing the Reichswehr.” Those who do not also see the positive cannot achieve a republicanization of the Reichswehr. With his speech, which was received positively, Severing helped to win a majority for the slightly modified Commission draft. The right wing of the SPD was also promoted by Severing when he contributed 5000 M from a government fund to the protection of the republic in 1929 to found the new theoretical body “New papers for socialism”. Without this capital, the publication would not have been possible.

Against the political extremes

During a cabinet crisis in which the center withdrew its minister Theodor von Guérard from the government, Severing also took over his post as minister for the occupied territories. After the return of the center on April 13, 1929, the government was initially strengthened. The right-wing political camp protested against the Young Plan, which was brought about by Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann in particular, to regulate reparations. In particular, Hugenberg pushed a referendum against the Young Plan . Severing was at the forefront of those who opposed this referendum and defended themselves against the attacks by the Hugenberg press. In parts of the public, the referendum that ultimately failed was stylized as a fight between Hugenberg and Severing.

On the left, the KPD had meanwhile adopted the social fascism thesis and agitated mainly against the SPD. In particular, the Red Front Fighters Association (RFB) tried to provoke. The Prussian police cracked down on a prohibited demonstration on May 1, 1929. There were civil war-like conflicts in Berlin, the so-called Blutmai . As a result, Grzesinski urged Severing to issue a nationwide ban on the Red Front Fighters League. To put pressure on the Reich Interior Minister, Grzesinski had the RFB in Prussia banned beforehand. Ultimately, the state interior ministers passed a corresponding ban. Severing himself was skeptical of the procedure because the step had contributed to the radicalization of the KPD. He did not consider any further plans for a ban on the KPD as a whole to be feasible.

In view of the developments on the extreme left and right, Severing felt that an extension of the Republic Protection Act, which expired on July 22, 1929, was necessary. A first draft failed in the Reichstag. A slightly weakened draft that no longer required a two-thirds majority in parliament was finally adopted.

Although the democratic system was already fragile, Severing, as the keynote speaker at the celebrations for the tenth anniversary of the constitution, emphasized that the republic was willing to fight off its enemies.

End of the Müller government in 1930

The republic was threatened economically by the beginning world economic crisis. Domestically, the DVP in particular began to push the SPD out of the government after Stresemann's death. Initially, Severing repeatedly advocated concessions to the bourgeois parties. In the end, however, the demands of the other side went too far for him too. In the decisive conflict during the budget deliberations for 1930, he rejected the Reich Finance Minister's draft on behalf of the SPD ministers because it contained no direct taxes to attract the property owners. Severing advocated direct tax increases to cover the crisis-related deficit in unemployment insurance, for example in the form of a surcharge on income tax. The DVP expressly opposed this. The intense dispute over the budget could be settled again. On March 27, 1930, however, the Müller government broke up in the dispute over unemployment insurance. This was preceded by a compromise proposal by Heinrich Brüning , which in essence came closer to the DVP and would have meant a socio-political shift to the right. Nevertheless, Severing pleaded for the adoption of this proposal in order to save the government, but was unable to assert himself in the SPD. In his opinion, accepting the compromise would have been better than leaving the republic to the right-wing parties. Severing commented on this in the Reichstag: “... this resignation was not an ordinary resignation, but the conclusion of a political period in which it was possible for social democracy to directly influence Reich politics. It does not take a prophetic gift to predict that the course should now be deliberately steered without social democrats, on several issues also against them. "

Prussian Interior Minister in the crisis of the republic

After the end of his ministerial tenure, Severing was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Braunschweig Technical University . Because of threats from National Socialist students, the award ceremony was not held in public.

Especially after the Reichstag elections of 1930 with the successes of the KPD and NSDAP, Severing, Braun and Heilmann spoke out in favor of tolerating Heinrich Brüning's government by the SPD parliamentary group. For them, the first presidential government was the lesser of two evils in the face of the rise of National Socialism.

In place of Grzesinski, who had to resign because of a private affair, Severing was again Prussian Minister of the Interior on October 21, 1930 after Heinrich Waentig's brief term in office . However, Severing was not the first choice for Prime Minister Braun. A renewed appointment of Grzesinski met with stiff resistance from the coalition partner of the Center Party. Braun's hesitation was based on the assessment that Severing was not active enough. On the part of the majority of Republicans, however, the assumption of office was seen as a hope for a successful fight against the political extremes. Der Vorwärts wrote: "The appointment of Carl Severing as Prussian Minister of the Interior will be seen in all circles as a response to the National Socialist dictatorship and coup plans." The paper once again praised the democratization of the administration and the creation of the "Severing System," against the " the whole anger of the disempowered Junkers and reactionaries rose up. ”On the other hand, the extreme right saw the appointment as a provocation, and for the communists Severing was the“ embodiment of social fascism. ”Severing himself was ready to fight. "He is not tired of fighting, and if someone tried to feel his pulse in the Reichstag last Saturday, he could explain to his opponents that he had deleted the word 'sickly' from his dictionary."

A first conflict was the campaign that Joseph Goebbels in particular directed against the film In the West Nothing New, based on the novel by Erich Maria Remarque . Severing and Grzesinski, who was appointed police president of Berlin, had the cinemas guarded and forbade demonstrations by the National Socialists. However, the film was banned a short time later at the instigation of the Reich government and the Reich President. Severing soon had to realize that the police force was only of limited use as the republic's protection force. The majority of the police, especially the officers, tended to wear steel helmets and the NSDAP. In order to counter the social hardship of the global economic crisis and thus the political radicalization, Severing actively participated in the development of winter aid. Not least at Severing's insistence, Brüning took the initiative to issue an emergency ordinance that made it possible to take better action against political extremists than before. This was followed by other similar emergency decrees of the Reich. However, this also involved restrictions on basic rights. In the first three months, more than 3,400 police actions due to political crimes were counted, the majority of over 2,000 cases being directed against the KPD.

Severing had to allow the referendum by right-wing parties to dissolve the Prussian state parliament , as it was constitutional. However, he forbade active support of the project by officials and police officers. He turned the KPD against him when he had a communist Spartakiad banned. This reinforced the communist party's goal of overthrowing the “social-fascist Braun-Severing-Grzesinski system”. One consequence was that the KPD supported the ultimately failed referendum by the NSDAP and other right-wing parties.

The measures of the governments in the Reich and in Prussia proved to be largely ineffective in combating politically motivated acts of violence. However, Severing did not consider a ban on the KPD possible. If the SA were banned , he saw the danger that the National Socialists would infiltrate the Stahlhelm instead. At the end of 1931 Severing used the Boxheim documents to once again inform the public about the National Socialist threat. Various ideas, such as deporting Adolf Hitler as an undesirable foreigner, failed because of the objection of the Reich government.

When the presidential elections came up in 1932 and Braun, Brüning and others wanted to nominate Hindenburg as republican candidates, Severing was skeptical, as he knew that the president often listened to advisers from the right-wing camp. Instead, he proposed the popular and republic loyal captain of the zeppelins Hugo Eckener to no avail . When the decision for Hindenburg had been made, Severing stood up for him with all his energy. So he organized the "republican action", which advocated the election of Hindenburg across party lines. He also succeeded in acquiring funds from the Reich government and Prussia for the election campaign against Hitler.

Severing had the NSDAP's buildings searched between the two presidential elections. Substantially harmful material such as purge lists were found. Against this background, Severing began to lobby the Reich government for a ban on the SA. The advance was successful, but the SA ban that came into force on April 13, 1932 was largely ineffective because the NSDAP had been warned by employees from the Prussian Ministry of the Interior.

Executive state government in 1932

In the Prussian state elections, Severing von Goebbels was seen as the real opponent. The Gauleiter of Berlin wrote: “The fight for Prussia, Herr Severing, is being waged for your name and for your person.” Goebbels subsequently led a dirty campaign with alleged private disclosures. But it was above all the general political situation that resulted in the NSDAP and KPD gaining a negative majority after the elections. The previous government officially resigned, but continued to operate until a new government was elected. After the election, various possibilities were discussed to come back to a government with a majority in the Prussian state parliament. This included an alliance between the center and the NSDAP. Severing has - surprisingly for many - advocated participation in the government of the Hitler party, because he believed that the movement could be disenchanted in this way. Later he tried to put this into perspective. Only if it is clear that the National Socialists could not cause any damage, their participation in government can be tolerated. Instead, he now advocated that the cabinet should remain in office for a longer period of time. “Staying until the replacement and doing his duty undaunted, whatever may come - that is perhaps the heaviest sacrifice that has so far been demanded by the party and by the next people involved. But it has to be brought because the constitution and the well-being of the people demand it. ”After Otto Braun's de facto withdrawal, Severing was the dominant figure in the executive government. He even tried to get an administrative reform through. The situation became difficult for the Prussian government after the fall of Brüning.

Prussian strike

The Papen worked out on to the elimination of the caretaker Prussian government from the beginning. This project appeared unconstitutional to the government, and other state governments also sided with Prussia. The so-called “ Altona Blood Sunday ” was a welcome occasion for the so-called Prussian strike . The appointment of a Reich Commissioner for Prussia was already being discussed in public. In this context, the editor of Vorwärts Friedrich Stampfer made it clear with the sentence that Severing had no right to be brave at the expense of the police officers, that the SPD would not actively oppose a disempowerment in Prussia. On the morning of July 20, 1932, von Papen Severing, the deputy prime minister Heinrich Hirtsiefer and finance minister Otto Klepper , whom he had appointed to his office, announced that Hindenburg would allow him, Papen, because of the inability of the Prussian government to exercise justice and law because of the inability of the Prussian government to be proven at the Altona Blood Sunday To guarantee Prussia would have been appointed Reich Commissioner for Prussia. He took over government affairs and first dismissed Prime Minister Otto Braun and Severing. The Ministry of the Interior will be taken over by the Mayor of Essen, Franz Bracht . The Prussian ministers protested against these measures and called them unconstitutional. Severing declared: "I just give way to violence." Then Berlin was immediately under siege and the Reichswehr deployed. The Prussian ministers, however, completely refused to offer any resistance. The Prussian police were not used. On the afternoon of the same day, Severing, who commanded 90,000 Prussian police officers, had himself driven out of his office and ministry by a delegation of the newly appointed police chief and two police officers. Other senior Republican police officers, as well as other Democratic-minded officials, were dismissed immediately and for the next few days. Klepper was appalled by Severing's fatalism and passivity, as he reported in the Paris-based exile magazine Das Neue Tagebuch - in his article Memory of July 20th in 1933 . As the only countermeasure, the ministers appealed to the State Court . Even if the government was partially right in the hearing before the State Court in the autumn, the ministers had lost their real influence by giving up their posts.

Contrary to the expectations of many supporters of social democracy and the republic, Severing did not advocate active resistance to the Prussian strike. On the one hand, objective reasons played a role. In view of the high unemployment rate, a general strike was not very promising, the battle of the police against the Reichswehr could not be won, and the Reichsbanner was also not as strong as it appeared. Personal reasons were particularly important. Severing had resigned inwardly and was no longer ready for an effective defense. Had he really stood firm, he might have forced Papen to compromise.

After the Prussian strike, Papen immediately began to reshuffle the heads of the authorities. Republicans were sacked. Although meetings of the powerless state government continued to take place, Severing rarely attended them. Instead, as a symbol of the Republicans, he found himself in an almost constant election campaign. He was the last SPD politician who could give an election campaign speech on the radio. His commitment did nothing to change the party's loss of votes. In the final phase of the republic Severing was one of the few leading social democrats who advocated supporting the new Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher in order to prevent Hitler.

time of the nationalsocialism

Beginning of the National Socialist rule in 1933

In the course of the dissolution of the Prussian state parliament planned by the new government, accusations were raised against Severing and Braun that they had embezzled state funds. These were funds that the government had made available in 1932 to fight the opponents of the republic. A real smear campaign against Severing and Braun began. Both of them took legal action against the allegations in vain. In the corresponding debate in the state parliament on February 4, 1933, Wilhelm Kube said on behalf of the NSDAP to Severing: "They are not a political matter for us, they are a criminal matter for us." Preventing MPs by shouting. The election campaign for the Reich and Landtag elections in March 1933 could only be carried out to a limited extent by the SPD. Severing, for example, was only allowed to give two campaign speeches. He was arrested on charges of embezzling state funds, but released at the session of the Reichstag at which the Enabling Act was discussed. At the vote in the Reichstag he was the last to cast his vote. He reported: “The presence of SA and SS men in the corridors and in the conference room of the Kroll Opera reinforced the threatening tone of the announcement. (…) With the no card in my right hand I went from my seat through the ranks of the SA and SS people to vote (…) “Severing no longer took part in the vote on an enabling law for Prussia on May 18, 1933 , since he had already resigned from his state parliament mandate.

Severing deliberately did not emigrate. He did not want to leave his supporters alone, especially in Bielefeld. Nor could he imagine living abroad. Severing belonged to that part of the SPD leadership around Paul Löbe , which fought against the leadership of the party in exile in Germany until the SPD was banned and tried to adapt to the new conditions.

Life in the time of the Nazi regime

In the following years Severing was no longer arrested, nevertheless he had to endure harassment and was monitored. Due to threats from the SA, for example, he had to leave Bielefeld several times, but otherwise remained unmolested. He himself withdrew completely from the public and initially stayed away from resistance groups. Severing kept in close contact with former leading Social Democrats during the Nazi era, however, also through trips.

Although he made his attitude towards the regime clear in small gestures such as refusing to raise the swastika flag, he was also instrumentalized by the regime. While the exile SPD demanded voting against the Anschluss in the vote on the integration of the Saar area , Severing spoke out in favor. Behind this was the conviction that the regime would only exist for a short time, but there was a risk that the Saarland would remain outside of the Reich territory for a long time. For the exiled SPD, the interview was so outrageous that it believed it was a fake.

Even during the Third Reich there were rumors that Severing had turned to the regime. In March 1934 a communist newspaper published in Saarland reported that Severing would publish his memoirs under the title “Mein Weg zu Hitler”, and the paper printed alleged excerpts. There was a heated debate in the emigration as to whether this was true. The campaign quickly turned out to be unfounded, but the suspicion was used politically against Severing by interested parties even after 1945.

For Severing's relationship to the Nazi regime, the payments he received from the regime are problematic. A distinction must be made between two aspects. Legally represented by his son-in-law Walter Menzel , Severing succeeded in enforcing the payment of the transitional allowance, which the regime refused to give him and the other members of the former Prussian government. The same applies to the payment of a small pension of 500M. More problematic than this legally entitled money is an additional payment of 250 RM, which came from a private fund of Hitler. Why he received this payment and why he accepted it is unclear. The allegation made after the war that he made a deal with the regime is wrong.

Relationships with Resistance

During the Second World War , his son died at the front. The numerous bomb attacks on Germany made it clear to Severing that a continuation of the war would end in catastrophe. Therefore, he began to contact resistance groups, in particular Wilhelm Leuschner and Wilhelm Elfes . Together with this former center politician, he planned the establishment of a workers 'party for the time after Hitler, which would overcome the previous division of the workers' movement into Christian, Communist and Social Democratic factions. As a former minister he also played a role in the personnel planning of the resistance. Severing refused any further participation or even active participation because he saw the planned overturn as far too risky and unrealistic. Despite his contacts, Severing was not arrested as part of the grating action after the failure of the Hitler attack on July 20, 1944 .

post war period

Influence without a mandate

Immediately after the end of the war, Severing advised the initially American and later British occupation authorities on filling vacancies, even though no Social Democrats were appointed to the post of Lord Mayor of Bielefeld and Social Democrats were not represented in the first advisory city council. The SPD in Bielefeld and East Westphalia was re-established in his house. Severing also played the leading role in the party in the following years. His ideas of a workers' party that bridged the boundaries of the political camps were not realized, however. Relations with Kurt Schumacher had been strained since the Weimar Republic, but they had at least a temporary common basis for cooperation with the goal of preserving German unity and in rejecting the collective guilt thesis . Nevertheless, the contrasts remained great. Severing rejected Schumacher's rigor. Instead of confrontation, he relied on cooperation between the SPD and the other democratic parties. Severing's efforts to get into conversation with the Christian churches and especially with Catholic circles also remained alien to Schumacher.

Severing was important for the democratic rebuilding beyond the borders of Bielefeld. He was the chairman of the Oelder Conference , at which representatives of various social groups met in order to use the “Oelder Call” to create a basis for a new political beginning. The public impression was so great that Severing also led a comparable conference for the Rhineland.

On September 3, 1945, senior administrators of the British zone met at his home. They appointed the Hamburg mayor Rudolf Petersen and Severing as the German liaison officers with the occupation authorities. Due to the death of his wife, Severing could not take part in the Wennigs conference at which Kurt Schumacher asserted his claim to leadership for the SPD in the western zones . In the area of the British zone, the regular conferences of the individual countries were to take place under Severing's chair. He appointed the staff for a liaison secretariat. He also negotiated with the Ruhr miners in order to persuade them to produce larger quantities and made proposals to reform the police. Without a formal office, Severing had such a strong position as never before. In October 1945 Severing was able to speak at large gatherings about the official approval of the SPD in Bielefeld.

Campaign against Severing

Severing's influence began to decline significantly as early as autumn 1945. The background was a campaign initiated by the East German KPD, in which he was accused of having received a pension from the Nazi regime. He was also accused of his behavior during the Prussian strike. There were even reports from western countries that Severing had signed a declaration of commitment in favor of Hitler. In addition to the deliberate intent to denounce the allegations, there was a lack of clarity as to why Severing was able to survive the Nazi era largely unmolested. Severing tried to take offensive action against the campaign with little success.

But there was also criticism in the SPD. Severing, Löbe and Noske seemed unsuitable as leaders for a new beginning. Schumacher saw it similarly and used the campaign to oust Severing from the leadership of the SPD. Severing's idea of an ideology-free workers' party was also sharply rejected by Schumacher. The fact that the SPD in the province of Westphalia did not put him at the top when drawing up the state list for the first state elections in North Rhine-Westphalia made him bitter.

Not only the personal attacks on Severing, but also the image that the Western Allies had of him, led to a weakening of his position. The French in particular saw his activity as an attempt to revive Prussia in the British zone. Against this background, the British saw Severing's position as chairman of the conference of country leaders in negotiations with the French and Russians as particularly disturbing. He resigned from office under pressure from the British occupation authorities. In 1946, he was also not appointed to the advisory provincial parliament of the Province of Westphalia .

State politician

The British initially refused him a license for the newly founded party newspaper for East Westphalia and Lippe ( Free Press ) . After all, Severing wrote the leading article in the first issue and presented the paper. This was more broadly based than the People's Watch from before 1933. The aim was not only to appeal to workers and staunch social democrats, but also to reach other readership groups. Severing headed the editorial office.

Although he was only of minor importance nationally, Severing remained the leading head of the SPD in East Westphalia , whose leadership positions were occupied by his followers. At the first party congress of the East Westphalian-Lippe SPD in late April 1946, Severing was elected district chairman.

Severing and others were successful with his work against the annexation of East Westphalia to a new, large Lower Saxony . During the negotiations to form the first cabinet of North Rhine-Westphalia under Rudolf Amelunxen (Center Party), Severing was head of the negotiating delegation of the SPD. The arguments with Konrad Adenauer were particularly fierce, who mainly opposed the occupation of the Interior Ministry with Severing's son-in-law Walter Menzel . He blamed Severing for the fact that a government eventually came about without the CDU. In the election for the first elected state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia on April 20, 1947, Severing was elected to the state parliament, to which he belonged until his death. In 1947 he was again instrumental in the negotiations for a new government. In the state parliament itself, Severing was a moral authority, he took his mandate very seriously. He gave the speech for the inauguration of the state parliament building.

Last years

Before the first federal elections in 1949 , Severing hoped for first place on the North Rhine-Westphalian state list in recognition of his life's work, although he did not think of accepting the mandate. When the party did not follow suit, he did not run again for the chairmanship of the SPD district of Ostwestfalen-Lippe. Instead, he became honorary chairman. He had previously given up the management of the Free Press for health reasons. However, he continued to write numerous articles.

The last two years of life were marked by illnesses. Nevertheless Severing continued to speak at important party events and visited old friends. Among other things, he visited Otto Braun in Switzerland. They settled the conflicts from the Weimar period. But at the turn of the year 1951/52 he got involved in the political debate and supported a campaign by Otto Grotewohl or the SED and KPD for reunification. Kurt Schumacher strictly opposed this course, and Severing even announced that he wanted to overthrow it. This was no longer due to illness and because of the knowledge that the SED had abused it.

When he died, he had lost almost all political influence. But after his death it turned out that he was still highly respected. The state parliament held a memorial service. Up until the funeral, thousands took the opportunity to pay their respects to those who were laid up. More than 40,000 people attended his funeral procession. Carl Severing was buried in the Sennefriedhof .

Trivia