Wilhelm Leuschner

Wilhelm Leuschner (born June 15, 1890 in Bayreuth ; died September 29, 1944 in Berlin-Plötzensee ) was a German trade unionist and social democratic politician who fought in the resistance against National Socialism . After July 20, 1944 , he was denounced, sentenced to death and executed.

Life

Wilhelm Leuschner was born on June 15, 1890 as Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Dehler on the first floor of Moritzhöfen 25 in Bayreuth. His mother was Marie Dehler, his father Wilhelm Leuschner was a foreman in a nearby furnace factory . In March 1899, after the marriage of his parents, he was registered as a legitimate child in the municipal registry office and from then on bore his father's surname.

In 1904 he began an apprenticeship as a wood sculptor , after which he joined the trade union in 1907. He then went on a hike in July 1907, worked a. a. in Leipzig and came to Darmstadt on the occasion of the Art Nouveau exhibition in 1908 , where he worked in the court furniture factory Ludiwig Alter. In 1909 he returned to Bayreuth and studied from October 1909 to March 1910 at the Royal School of Applied Arts in Nuremberg (today the Academy of Art). In the summer of 1911 he married Elisabeth Batz in Darmstadt and had two children with her (Wilhelm born in 1910 and Katharina born in 1911). From 1911 he worked as a wood sculptor at the international furniture factory Glückert .

Wilhelm Leuschner had been a member of the Masonic Lodge Johannes der Evangelist zur Eintracht in Darmstadt since February 7, 1923 .

Political attitude

The democratic attitude of Wilhelm Leuschner crystallizes in the letters of his friends. As the Hessian and social democratic interior minister, he tried to preserve democracy in his country and supported all those who wanted to strengthen democracy in Germany and who resisted the National Socialist, anti-democratic regime.

Ludwig Hoch, a Saxon police officer and good friend of Leuschner, congratulated Leuschner on his election victory on February 24, 1928, because the SPD not only emerged as the big winner in the Reichstag election of May 20, 1928 with 29.8 percent Leuschner himself was appointed Minister of the Interior of Hesse in the same year. Hoch was very happy about the rise of the SPD and was pleased "that this year the parliamentary group is finally getting serious about long-term demands" and also claimed that Leuschner was portrayed positively by the press in Saxony. But the policeman also pointed out to his friend the difficulties that Leuschner would have to overcome in his office. Leuschner was warned by Hoch not to trust his employees too much, as there are dangers even in their own ranks, i.e. among the SPD members. Because many who claimed to be true SPD members turned out to be traitors in the end. As an example, Hoch cited the Hessian police officer Hamberger, who would not have acted loyally to the SPD. Ultimately, Hoch formulated his goal of building a democratic police force in both Saxony and Hesse, although the implementation was very problematic.

Leuschner also had a good relationship with the members of the Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold, as he himself had an important role in this organization. The Reichsbanner had set itself the goal of defending and protecting democracy. So did the head of the Reichsbanner, Otto Hörsing, who also admitted in a letter to Leuschner to fight against right and left radical organizations or parties and thus for democracy. The Reichsbanner consisted of 90 percent SPD members, the remainder were supporters of the Center Party and the German Democratic Party (DDP). The democratic orientation also explains why the Reichsbanner was banned by the National Socialist government in 1933 due to its resistance to the Nazi regime.

In the first World War

In October 1916, 26-year-old Wilhelm Leuschner was drafted into military service. He served in a so-called light measuring squad , whose task it was to determine the distance of the enemy positions based on the muzzle flash. He came by train from Frankfurt via Görlitz, Brockau and Warsaw to Pinsk in Belarus, where he was initially stationed. In May 1917 he was transferred to the Western Front near Verdun.

It was in Belarus that Leuschner first came into contact with Orthodox Jews. He visited the local Orthodox synagogues and churches of the local population with great interest. Leuschner was fascinated by the people and their beliefs and how they practiced it, unlike the German population he knew. In his diaries he described everyday war life and clearly showed how he perceived the war. With the beginning of the November Revolution on November 9, 1918, Wilhelm Leuschner was unanimously elected chairman of a soldiers' council on the Western Front near Verdun.

Leuschner's activities during the war are impressive; he learned English and French so well that he was able to converse well with the people there during his stationing in France. In addition to learning languages, Leuschner had trigonometry explained to him and read books of various kinds to further educate himself.

Trade unionist and Hessian interior minister

In 1909 he became head of the Darmstadt district of the sculptors' association. In 1913 he joined the SPD and continued to be involved in the union. In 1916 he had to serve as a soldier on the Eastern Front during the First World War , and later also in the West. In 1919 he became a city councilor and chairman of the Darmstadt trade unions, and in 1924 he entered the state parliament of the People's State of Hesse (i.e. southern Hesse or the former Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt ) as an SPD member . In 1927 he acted as a representative of the workers' interests on the board of directors of the newly founded Reichsanstalt für Arbeitsvermittlungs und unemployment insurance . In 1928 he became Minister of the Interior of the People's State of Hesse . Leuschner, who was previously considered a police expert in the SPD parliamentary group, exposed himself as a defender of the democratic constitution. Ludwig Schwamb and Carlo Mierendorff were among his closest employees in the ministry .

Leuschner explicitly acknowledged the equal rights of all citizens, regardless of their origin or social origin. During his tenure as Hessian Minister of the Interior, the law to combat the gypsy insanity (Gypsy Law ) presented by his predecessor Ferdinand Kirnberger ( center ) was passed in a weakened form by the Hessian state parliament. Although Kirnberger was still a Cabinet Minister as Justice Minister , the definition of Gypsies on the basis of their “racial affiliation” had been deleted. In the state parliament committee, SPD members had questioned the constitutionality of the law and had demanded the complete removal of the term "gypsies". During the decision-making state parliament debate, however, only one member of the KPD spoke out against the government bill. With regard to the Sinti and Roma, the law was an expression of the antiziganism that was widespread even among democrats at the time, which is why some count the law to the prehistory of the systematic murder of the Sinti and Roma under National Socialism .

Leuschner was a staunch opponent of National Socialism. After he had initiated the publication of the Boxheim documents , plans to seize power drawn up by the NSDAP MP Werner Best , he became a personal enemy and Leuschner one of the most hated opponents of the National Socialists. The Boxheim documents clearly showed the intended establishment of a terrorist regime; they indicated that the National Socialists' legality course was a mere facade.

persecution

In January 1933 Leuschner was elected to the federal executive committee of the General German Trade Union Confederation . On April 1, Leuschner resigned from his position as Hessian Minister of the Interior after the Nazis had been forced to resign after the Nazis had come to power. In the first few months of the National Socialist regime, Leuschner took part in conspiratorial deliberations on the formation of a unified trade union - plans in which Jakob Kaiser , among others, was involved, but which could not be implemented. Since he steadfastly as the de facto union leaders by Robert Ley refused desired collaboration with the Nazis, it came in May of the same year to his detention . The unions were smashed. In June 1933 he was arrested again, mistreated and held for a year in prisons and concentration camps , including the Emsland camp Börgermoor .

resistance

However, the National Socialists did not achieve their essential goal, namely the bowing of personality. Soon after Leuschner was released from the concentration camp in June 1934 , he began to build a resistance network. In 1936 he took over from Ernst Schneppenhorst the management of a small factory for the production of beer dispensing utensils, which soon became the control center of the illegal Reich leadership of the German trade unions. During this time, Hermann Maaß became one of his closest collaborators. Leuschner actively fought in union-affiliated resistance groups and maintained contacts with the left-wing socialist resistance group Red Shock Troop and its Berlin leader from 1934 Kurt Megelin . His wife Else Megelin was employed by Leuschner as a secretary in his Kreuzberg company for camouflage purposes. Leuschner and the Red Shock Troop also maintained connections to the Kreisau Circle and, from 1939, to the resistance group of Carl Friedrich Goerdeler . Within this heterogeneous circle, Leuschner was seen as a representative of the trade unions, i.e. a mass base, and at the same time as a fighter against the establishment of a corporate state order after the intended overcoming of the National Socialist regime. After the planned putsch against Hitler, Leuschner should possibly become Vice Chancellor in the Beck / Goerdeler shadow cabinet ; the national conservative Count von Stauffenberg , who carried out the assassination attempt on Hitler, is even said to have personally favored Leuschner as Chancellor over Goerdeler. The assassination attempt on July 20, 1944 and the attempted coup failed, however. Leuschner fell victim to a denunciation on August 16, 1944 and was arrested. He was then sentenced to death by the People's Court , chaired by Roland Freisler . On September 29, 1944, Wilhelm Leuschner was executed in Berlin-Plötzensee prison .

Commemoration

The Wilhelm Leuschner Medal , the highest award in the State of Hesse , has been named after Leuschner since 1964 .

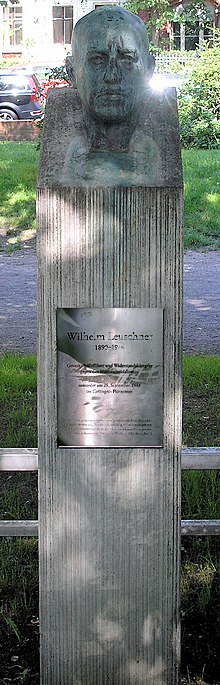

The northern section of the former Elisabethufer in Berlin-Kreuzberg has been called Leuschnerdamm since July 31, 1947. There is a memorial stele with the bust of Leuschner, while a few meters away, on the opposite side of the former Luisenstadt Canal , the Legiendamm, there is a stele with a bust in honor of Carl Legien .

In 1998 the Wilhelm-Leuschner-Gedächtnis-Zimmer was set up at the Marienkirche Rockenberg in the penal institution (former penitentiary) where Leuschner was imprisoned from July to November 1933, which documents the person and work. The memorial is difficult to access due to the continued existence of the youth detention center there.

The Wilhelm Leuschner Memorial has been located in Leuschner's Bayreuth birthplace since 2003 . There was also the seat of the Wilhelm Leuschner Foundation, which largely designed the exhibition in terms of content. It has been based in the Wilhelm-Leuschner-Zentrum Bayreuth at Herderstrasse 29, a few meters from the memorial site, since 2012, and offers educational work primarily for school classes. She also keeps Leuschner's estate and works on it scientifically. An archive exhibition in the center serves educational work. The foundation operates a website on the life and work of Leuschner.

Numerous schools, streets and squares are named after Leuschner, including a school in Darmstadt and a square in Leipzig . In January 2018, according to Zeit Online, there were 158 streets , paths and squares in Germany, especially in western Germany and especially in Hesse.

literature

- Literature by and about Wilhelm Leuschner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Ludger Fittkau, Marie-Christine Werner: The conspirators. The civil resistance behind July 20, 1944. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2019, ISBN 978-3-8062-3893-8 .

- Eberhard Flessing: Leuschner, Wilhelm. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , p. 380 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Hessian State Chancellery (ed.): Wilhelm Leuschner, mandate and obligation. With a picture of Leuschner's life by Wolfgang Hasibether. 2nd edition, Wiesbaden 2011.

- Joachim G. Leithäuser : Wilhelm Leuschner. A life for the republic. Bund, Cologne 1962.

- Jochen Lengemann : MdL Hessen. 1808-1996. Biographical index (= political and parliamentary history of the state of Hesse. Vol. 14 = publications of the Historical Commission for Hesse. Vol. 48, 7). Elwert, Marburg 1996, ISBN 3-7708-1071-6 , p. 242.

- Siegfried Mielke , Stefan Heinz : Railway trade unionists in the Nazi state. Persecution - Resistance - Emigration (1933–1945) (= trade unionists under National Socialism. Persecution - Resistance - Emigration. Volume 7). Metropol, Berlin 2017, ISBN 978-3-86331-353-1 , pp. 30, 92, 205, 214-260, 264, 277, 334, 337, 377, 411 ff. (And numerous other references).

- Hans Mommsen : The resistance in the Third Reich. In: ders .: On the history of Germany in the 20th century. Democracy, dictatorship, resistance. Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-421-04490-7 , pp. 235-348.

- Klaus-Dieter Rack, Bernd Vielsmeier: Hessian MPs 1820–1933. Biographical evidence for the first and second chambers of the state estates of the Grand Duchy of Hesse 1820–1918 and the state parliament of the People's State of Hesse 1919–1933 (= Political and parliamentary history of the State of Hesse. Vol. 19 = Work of the Hessian Historical Commission. NF Vol. 29) . Hessian Historical Commission, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-88443-052-1 , No. 535.

- Peter Steinbach : July 20, 1944. Faces of resistance. Siedler, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-88680-155-1 , chapter “The state beats people” - Wilhelm Leuschner , pp. 111–127.

- Reiner Tosstorff: Wilhelm Leuschner against Robert Ley. Rejection of the Nazi dictatorship by the International Labor Conference in Geneva in 1933. Publishing house for academic writings, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-88864-437-5 .

- Reiner Tosstorff: Leuschner against Ley. The rebuff for the Nazis at the 1933 International Labor Conference in Geneva. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement . Volume III, 2004.

- Johannes Tuchel: On the persecution of trade unionists after July 20, 1944. The Gestapo investigations and the show trial of Wilhelm Leuschner before the National Socialist "People's Court" . In: Ursula Bitzegeio, Anja Kruke, Meik Woyke (eds.): Solidarity community and culture of remembrance in the 20th century. Contributions to trade unions, National Socialism and history politics . Dietz, Bonn 2009 (Historical Research Center of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation - Series: Political and Social History, Vol. 84), ISBN 978-3-8012-4193-3 , pp. 329-360.

- Axel Ulrich: Wilhelm Leuschner - a German resistance fighter. For freedom and justice, democratic unity and a social republic. Preface by Helga Grebing . Thrun, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-9809513-9-5 .

- Axel Ulrich, Stephanie Zibell: Wilhelm Leuschner and his anti-Nazi confidante network. In: Wolfgang Form, Theo Schiller, Lothar Seitz (editor): Nazi justice in Hessen. Persecution, continuity, legacy. Historical Commission for Hessen, Marburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-942225-28-1 , pp. 293–334.

- Axel Ulrich: "Stick together. Build everything up again." On the resistance of Wilhelm Leuschner and his dung riders. In: Christian-Matthias Dolff, Julia Gehrke, Christoph Studt (eds.): "Be united, united against Hitler!" Forms, goals and motives of resistance from the left. Conference proceedings for the XXVIII. Königswinter conference. Wißner, Augsburg 2020 (publication series of the research community July 20, 1944 eV, vol. 23), ISBN 978-3-95786-233-4 , pp. 203-243.

Web links

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Homepage of the Wilhelm Leuschner Foundation

- Video about Wilhelm Leuschner

- Leuschner, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm. Hessian biography. (As of February 17, 2020). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Display board in the Wilhelm Leuschner Center in Bayreuth

- ^ Robert A. Minder: Freemason Politicians Lexicon , study publisher; Innsbruck 2004, 350 pp., ISBN 3-7065-1909-7 , p. 119.

- ^ Website of the lodge

- ↑ Hessisches Staatsarchiv Darmstadt I holdings: 029 Leuschner No. 48

- ^ Wilhelm Leuschner: From the German People's State. The meaning of the Weimar constitution, in: Julius Reiber, Karl Storck (ed.): Ten years of the German Republic. A memorial book for the 1929 Constitutional Day. Darmstadt 1929, p. 28.

- ^ Hessisches Regierungsblatt, No. 9, May 6, 1929, p. 66 f.

- ↑ http://www.hstad-online.de/ausstellungen/online/webhexen/Scheitern/Tafel29/Tabelle1.htm

- ↑ Document No. 452, Rapporteur: Abg. Dr. Niepoth. Report of the Second Committee on the Government Bill, “Draft Law to Combat the Gypsy Abuse” (printed matter No. 274) p. 1 f.

- ↑ http://www.hstad-online.de/ausstellungen/online/webhexen/Scheitern/Tafel29/Tabelle1.htm

- ↑ Udo Engbring-Romang: The persecution of the Sinti and Roma in Hesse between 1870 and 1950. Frankfurt a. M. 2001, p. 119ff.

- ↑ Dennis Egginger-Gonzalez: The Red Assault Troop. An early left-wing socialist resistance group against National Socialism. Lukas Verlag, Berlin 2018, compare among others pp. 290, 304ff. and 459f.

- ↑ See Hans Mommsen , Alternative zu Hitler. Studies on the history of German resistance, Munich 2000, p. 305.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hasibether :: A contender for unity and justice and freedom. Wilhelm Leuschner (1890 to 1944). A picture of life . In: Hessische Staatskanzlei (Ed.): In the service of democracy. The winners of the Wilhelm Leuschner Medal 1965 - 2011 . Self-published, Wiesbaden 2011, p. 13–37, here: 34 ff .

- ↑ Gerd R. Ueberschär : For another Germany. The German resistance against the Nazi state 1933–1945. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-596-13934-1 , pp. 215ff.

- ^ Wilhelm-Leuschner-Gedächtnis-Zimmer , Culture and History Association Oppershofen.

- ^ The Wilhelm Leuschner Foundation on the Internet

- ^ Search for Wilhelm Leuschner. In: Time Online , How Often Is Your Street There?

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Leuschner, Wilhelm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Member of the Reichstag, resistance fighter, victims of National Socialism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 15, 1890 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bayreuth |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 29, 1944 |

| Place of death | Berlin-Plötzensee |