Kapp putsch

The Kapp Putsch (also Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch , rarely Lüttwitz-Kapp Putsch ) of March 13, 1920 was a counter-revolutionary attempted coup against the Weimar Republic created after the November Revolution that failed after 100 hours (on March 17) . The leader was General Walther von Lüttwitz with the support of Erich Ludendorff , while Wolfgang Kapp only played a minor role with his " National Association ".

The attempted coup brought the republican German Reich to the brink of civil war and forced the social democratic members of the Reich government to flee Berlin. Most of the putschists were active members of the Reichswehr or former members of the old army and navy , especially the Ehrhardt Marine Brigade , who organized themselves into reactionary Freikorps after the First World War , as well as members of the German National People's Party (DNVP).

In addition to the refusal of the government bureaucracy and the disagreement among the military about the actual aim of the putsch, the following general strike , the largest in German history, played a large part in the failure of the putsch .

prehistory

The attempted coup was directed against the government under Gustav Bauer (SPD), supported by the SPD , the center and the DDP . However, there was no agreement between those involved about the objectives, which was mainly due to the hasty start and inadequate preparation. There were considerable differences between those mainly responsible, Kapp and Lüttwitz.

Although the Bauer government tried to weaken compliance with the provisions of the Versailles Treaty , it had to comply with it in the main. It came into force on January 10, 1920. Large parts of the officer corps of the Reichswehr and the members of the nationalist- oriented Freikorps did not want to accept the reduction of the Reichswehr to 100,000 men - and thus their dismissal.

The commanding general of Reichswehr Group Command 1 in Berlin, Walther Freiherr von Lüttwitz , headed the military opposition to the government. Political leadership was to be taken over by the Prussian general landscape director Wolfgang Kapp , who was a founding member of the German Fatherland Party during the war .

The Reich government itself tried to delay the dismantling of armed forces, since it saw itself dependent on the troops in order to master the violent social unrest in the Reich. Among other things, the Works Council Act led to a bloodbath in front of the Reichstag on January 13, 1920 . In addition, the question of the borders of the empire in the east was not yet resolved; Polish nationalists tried to create facts in favor of Poland in uprisings in Upper Silesia before the upcoming referendums .

background

The reasons given for the coup were the hostility to the republic and the frustration of many former soldiers, who were now organized in around 120 volunteer corps.

The specific trigger on February 29 was the order by Reich Defense Minister Gustav Noske to dissolve the Ehrhardt Marine Brigade , since the Versailles Peace Treaty came into force on January 10, 1920, which limited the German army to 100,000 men and the navy to 15,000 men. This meant a massive downsizing of the approximately 400,000 strong Reichswehr from 1919, and most of the Freikorps of that time were to be disbanded. On this point, however, the leaders of the Freikorps did not play along; the political generals were unwilling to forego the instruments of their political power, and so the military coup d'état of March 13, 1920 came about.

In particular, the so-called Baltic Freikorps (from which the Ehrhardt Marine Brigade was composed) continued to fight against the advancing Red Army of Soviet Russia even after the war . This was tolerated by the Allies. After the Latvian capital Riga was conquered in May 1919, the contract was considered to have been successfully completed. The following withdrawal order was ignored by the Freikorps. It was only when the Reich authorities interrupted supplies that the Freikorps gave up. The soldiers, disappointed by their government, met with the National Association founded in 1919 , a successor organization to the German Fatherland Party from the First World War, in which Wolfgang Kapp and Captain Waldemar Pabst set the tone. It primarily served to coordinate the already existing nationalist opposition groups.

The Ehrhardt Marine Brigade was militarily an elite unit and politically extremely hostile to the government and the republic. The day after Noske's decision to dissolve, the brigade held a large parade, without an invitation from the Reich Minister of War, on which General von Lüttwitz declared: “I will not tolerate such a core force being crushed in such a thunderstorm time. … ”With that he publicly disobeyed the government.

procedure

Over the next few days, Noske transferred the command of the Ehrhardt Brigade to the naval command, in the hope that they would carry out his order to dissolve.

At the beginning of March, Lüttwitz made contact with leading politicians from the right-wing conservative DNVP and the national liberal DVP , Oskar Hergt and Rudolf Heinze . He informed them of his demands (new elections to the Reichstag and direct election of the Reich President) and pointed out the possibility of a putsch. His demands largely coincided with those of the two parties. Hergt and Heinze promised to work towards a solution in the Weimar National Assembly, which still functions as parliament . At the same time they asked Lüttwitz to postpone his putsch plans for the time being. However, the motion for a resolution tabled by both groups on March 9th did not find a majority. The rumors of a putsch that had been circulating for some time had been ignored by Reichswehr Minister Gustav Noske.

On Wednesday, March 10th, General von Lüttwitz called on President Ebert and ultimately demanded the withdrawal of the dissolution order. At the same time he made various political demands, including the immediate dissolution of the National Assembly and new elections to the Reichstag. In the presence of Noske, Ebert rejected these demands and demanded that the general resign within the next 24 hours. The head of the Army Personnel Office, General Ritter and Edler von Braun , was instructed to persuade Lüttwitz to leave the service and be promoted to Colonel General . Since the voluntary resignation forthcoming, Lüttwitz was on March 11 by Noske because of insubordination against the civilian Reich authorities for disposition made.

General von Lüttwitz did not think to submit his dismissal and instead drove to Döberitz to the Ehrhardt Brigade. There he gave Ehrhardt the order to march on Berlin. Only then did he inform the group of conspirators of the “National Unity” around Kapp, Waldemar Pabst and Ludendorff. You should be ready to take over the government in Berlin on Saturday morning.

Corresponding rumors were already circulating in Berlin on Friday evening; Even Berlin evening newspapers carried reports of an impending putsch by the Ehrhardt Brigade, so that Noske ordered two regiments of security police and one regiment of the Reichswehr into the government district to defend it militarily if necessary. But the officers in charge of these three regiments informed the other units in and around Berlin that same night that they were not willing to obey Noske's orders to defend the government buildings.

On the night of March 13th, the Ehrhardt Brigade marched to Berlin, field marching like in enemy territory. Many soldiers wore a white swastika painted on their helmets as an expression of their ethnic outlook . From 11 p.m. the government was informed that the Ehrhardt Brigade was approaching; hectic activity broke out. Noske held a commanders' meeting at which he learned that the government district would not be defended by the three companies and that his order to shoot would not be obeyed. At the same time, a cabinet meeting was held in the Reich Chancellery under Ebert's leadership, at which it was decided that the government should flee Berlin and call for a general strike . Both resolutions were passed with a majority, not unanimously. Justice Minister and Vice Chancellor Eugen Schiffer (DDP) did not join the escape, while the call for a general strike was only signed by the Social Democratic ministers. At 6:15 a.m. the meeting was interrupted and the ministers fled with cars provided in the courtyard. Ten minutes later the Ehrhardt Brigade marched through the Brandenburg Gate with singing.

The social democratic members of the government first went to Dresden to see Noske's old “city conqueror”, the local military district commander Georg Maercker . They assumed they were safe there. Maercker had already received a telegram order from Berlin to put the ministers in “protective custody” upon their arrival. Only the accidental presence of the chairman of the German People's Party, Heinze, could dissuade Maercker from his plan. Nevertheless, Ebert and Noske preferred to flee further to Stuttgart, where the military had so far remained calm. Only a few government politicians stayed behind in Berlin, including Justice Minister and Vice Chancellor Eugen Schiffer (DDP) and Center Chairman Karl Trimborn , who later led the negotiations with the putschists.

The mutinous troops proclaimed Kapp Chancellor . The former Berlin police chief Traugott von Jagow , Colonel Max Bauer , Captain Waldemar Pabst and the pastor and DNVP politician Gottfried Traub were also involved in the putsch .

In a meeting between Noske, the head of the Army Command, Walther Reinhardt, and the head of the Troop Office, Hans von Seeckt , only Reinhardt spoke out in favor of deploying troops loyal to the government against the putschists, while Seeckt refused. Seeckts answer is often quoted with the words "Troops do not shoot at troops" or "Reichswehr does not shoot at Reichswehr". Even if there is no evidence for this, he expressed himself accordingly, because he feared that this would mean the destruction of the Reichswehr he had built up. Seeckt called in sick at the beginning of the coup and secretly participated in its liquidation from home. The troops of Group Command 1 in the eastern and northern parts of the Reich initially largely obeyed the orders of their immediate superior Lüttwitz, while those of Group Command 2 in West Germany waited. The Reichswehr leadership in Berlin was similarly divided.

On the morning of March 13, a call by the press chief of the Reich Chancellery, Ulrich Rauscher , was circulated for a general strike on behalf of the Reich President and the SPD ministers and parliamentary group; This was followed in the afternoon by the General German Trade Union Federation (ADGB) and the Working Group of Independent Salaried Employees' Unions (AfA). The Communist Party of Germany (KPD) also spoke out against the putsch, but initially asked the proletarians to wait before taking part in actions. The SPD, on the other hand, called for a general strike:

“Workers! Enjoyed! We did not make the revolution in order to submit to a bloody Landsknecht regime again today. We are not making a pact with the Baltic criminals ! … All or nothing! That is why the harshest repellants are required. ... Stop work! Strike! Cut the air off this reactionary clique! Fight for the preservation of the republic with every means! Leave aside all strife. There is only one remedy against the dictatorship of Wilhelm II: paralyzing all economic life! No hand can move anymore! No proletarian is allowed to help the military dictatorship! General strike across the board! Workers unite! Down with the counter-revolution! "

The members of the DNVP expressed solidarity with the coup plotters and, in some cases, actively supported the attempted coup. Parts of the DVP also sympathized with the putschists. The party leadership under Gustav Stresemann took the decision not to condemn the putsch, but in its declaration of March 13, they called for an early transition to an orderly situation.

After a meeting with representatives of the USPD and SPD in Elberfeld , on March 14th, the KPD corrected its position from the previous day and called for participation in the general strike. Individual districts of the party were already participating in the strike at the time. The Ruhr uprising arose in the Ruhr area , which developed as the Red Ruhr Army into an armed formation with 50,000 to 120,000 men and, like the simultaneous movements in Thuringia and Saxony, was to be transformed into a second revolution by the USPD.

In Berlin there were not only armed clashes between coup troops and troops of workers, but also a brief resurgence of the council movement . From March 17th, a new election of the Berlin councils was organized in the factories; on March 23rd, around 1,000 delegates met for the general assembly. The majority of them belonged to the USPD and KPD, but there were also representatives of the SPD. They voted against a continuation of the general strike, also because the unions had already decided that. The General Assembly later threatened several times with a restart of the strike. This was intended to stop the advance of government troops in the Ruhr area.

The Kapp putschists did not succeed in holding onto power in the days that followed. They did not find sufficient support and met resistance in the Berlin ministerial administration. Theodor Lewald , the longest-serving undersecretary of state (especially in the Ministry of the Interior) stated that, in contrast to 1918, there was no new legal situation, and so refused to pay the putschists, so that they were also financially drained. The German Association of Officials supported the strike from March 15. In addition, the military lacked agreement on their actual goals. The hasty nature of the coup is also evident from the fact that the coup plotters had not prepared any ministerial lists.

However, the general strike - the largest in German history - undoubtedly played a major role in the failure of the putsch. This general strike already completely gripped Berlin on Sunday, March 14th and spread across the whole of the republic on Monday. There was no rail traffic, no trams and buses in the cities, no post office, no telephone exchange, no newspapers, all factories and all authorities were closed. In Berlin there was no longer even water, gas or electric light. This general strike completely paralyzed public services and quickly made the putschists aware of the futility of their endeavors. He deprived them of any opportunity to rule.

On March 17th, Kapp finally fled to Sweden . Von Lüttwitz took over the government as a military dictator and wanted to act as such against the uprisings. However, negotiations in the Berlin Ministry of Justice took place on the same day, in which the party representatives under Justice Minister Eugen Schiffer Lüttwitz offered the fulfillment of some demands in return for the bloodless termination of the coup. In addition, they promised their commitment to an amnesty . They acted without the backing of the Reich government in Stuttgart, which had always refused negotiations. Since Lüttwitz had largely lost support in the Reichswehr, he agreed to the terms and resigned. The agreement was circulated in a press release on the same day. The attempted coup ended after five days. Lüttwitz left the Reich Chancellery , accompanied by Erich Ludendorff, whom the putschists had invited to deliberate on several occasions .

consequences

Because the Lüttwitz government called the Ehrhardt Brigade after Kapp's flight against the workers who continued to strike, it was able to continue for a while. The heavily armed security police (Sipo), also deployed, used aircraft bombs and heavy machine guns against strikers and insurgents.

The unions supporting the general strike agreed on March 18 on a joint nine-point program with far-reaching demands, including the socialization of businesses and the expropriation of large agrarians, as well as a government reshuffle. Otherwise, they wanted to continue the strike. After negotiations with the governing parties, a compromise was reached on March 20: the main demands of the nine-point program were accepted in a weaker form. However, under pressure from the USPD, further negotiations and further concessions in the field of military and security policy took place. After that, work resumed on March 23rd.

On March 26, the Bauer cabinet resigned and a new government under Hermann Müller (SPD) was formed ( Müller I cabinet ). A participation of the trade unions in the government did not come about, so the ADGB chairman Carl Legien had rejected the office of Chancellor offered him by Ebert. The new Reich Chancellor Müller appointed Hans von Seeckt as the new head of the Army Command after General Reinhardt had also resigned in solidarity with the Reich Defense Minister Noske, who was no longer tenable and forced to resign because of “promoting the counterrevolution ”.

In East Prussia, all senior administrative officials with the exception of Königsberg's Lord Mayor Hans Lohmeyer had joined the von Kapp company. After its failure, the state government dismissed the senior president August Winnig , three district presidents and most of the district administrators. Lord Mayor Lohmeyer, District President Matthias von Oppen ( Allenstein ) and District Administrator Heinrich von Gottberg ( Bartenstein ), Dodo Frhr , were not dismissed . zu Innhausen and Knyphausen ( Rastenburg ), Herbert Neumann ( Pr. Eylau ) and Werner Frhr. v. Mirbach ( Neidenburg ).

In the Reichstag election on June 6, 1920 , the Weimar coalition consisting of the SPD, the center and the DDP lost its absolute majority. A bourgeois minority government was formed with the Fehrenbach cabinet . The USPD, DNVP and DVP emerged as winners from the election . The amnesty passed on August 2, 1920 exempted all coup participants with the exception of the “authors” and “leaders”, unless they had acted out of “rawness” or “self-interest”. The same rules applied to the left-wing rebels. In the Reichswehr, 48 officers were dismissed from their posts following military court proceedings; most of the proceedings were either discontinued or ended with an acquittal.

Many leading participants in the putsch settled in the conservative " regulatory cell " of Bavaria , which was formed on March 16 as a result of Gustav von Kahr's takeover of government there , where they became involved in right-wing organizations and military associations . The former commander of the Ehrhardt Brigade founded the Consul organization in Munich as a quasi-successor organization , which was responsible for numerous murders of republican politicians in the period that followed.

On December 21, 1921, the Reichsgericht Traugott von Jagow sentenced to a minimum sentence of five years imprisonment (the mildest and most honorable form of deprivation of liberty for offenses and crimes). In this judgment it was said on the one hand that Section 81 (I) No. 2 StGB ( high treason ) should protect the current constitution of the German Reich and thus also the new Weimar constitution . On the other hand it said: "In the sentencing, the defendant Traugott von Jagow, who under the spell of selfless patriotism and followed Kapp's call for a seductive moment, was granted mitigating circumstances."

The proceedings against two co-defendants were dropped on the same day. These three trials were the only criminal cases against the coup plotters. Although Kapp presented himself to the Reichsgericht, terminally ill after his escape in April 1922, he died before his trial on June 12, 1922 in custody.

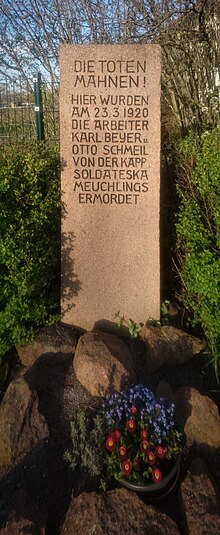

Commemoration

For the insurgents, soldiers, police officers and civilians who were killed in the fighting in numerous places in the German Reich and who had defended the republic, memorials and monuments were set up in the first few years. An extensive selection:

- Memorial to those who fell in March by Walter Gropius , erected on May 1, 1922 in the historical cemetery in Weimar for one female worker and eight workers

- Memorial plaque in the quarry of the Galgenberg in Halle (Saale) for the dead from the fighting there

- Memorial plaque at the entrance to the Halle -Lettin district, in the district of Lettin, two streets are named after the victims

- Stadtfriedhof Stöcken in Hanover-Stöcken Department 64 A: 1–8 and 13 (graves for 14 victims of the Kapp Putsch)

- Cenotaph on the southern cemetery in Gera , designed by Selmar Werner in 1921 (graves for 14 of the 15 workers who died in Gera); also memorial plaque at the Gera town hall

- Memorial plaque at the former location of the Schöneberg town hall on Berlin's Kaiser-Wilhelm-Platz for the victims of the coup

- Memorial stone for the victims of the Kapp Putsch in Berlin-Koepenick at the Grünau S-Bahn station

- Memorial stone for Alexander Futran on Futran-Platz in the old town of Köpenick in Berlin

- Memorial stone for the victims of the Köpenick Bloody Sunday on March 21, 1920 on Futran-Platz in Köpenick in Berlin

- Inscription on the town hall portal in Suhl (in the green forest the red city that had a 'town hall' shot up)

- Memorial stone for the suppression of the Kapp Putsch (cessation of fighting) in Zickra (district of Berga / Elster )

- Memorial plaque on the Spremberger Tower in Cottbus

- Plaque in Marburg , by the city and the University at the Old University was affixed to the murder of 15 workers on 25 March 1920 by a student volunteer corps to remember from Marburg, which largely from frat composed.

- Memorial plaque for the victims of Harburg's Bloody Sunday at the Woellmerstrasse school in Hamburg-Heimfeld , the then city of Harburg (Elbe) (see also: Rudolf Berthold )

- Memorial plaque commemorating the armed fighting in Riesa (Dr.-Külz-Straße)

- Memorial commemorating the killing of five unarmed citizens in Eisenach (Frankfurter Strasse)

- Grave site of the Schöneberg victims of the Kapp Putsch at the Eythstrasse cemetery in Berlin-Schöneberg (graves for three victims without relatives)

- Memorial stone on the New Cemetery in Senftenberg

- Memorial plaque in Bad Kösen at the location of the shootings

- Memorial stone for the workers killed by the Kapp putschists Karl Behrend, Max Hagen, Bernhard Birkhahn, Erwin Haack and Ernst Wulff in Greifswald

Graves of honor and memorial plaques in the Ruhr area / Rheinisch-Westphalian industrial area:

- Honor grave, Wiescherstraße cemetery in Herne

- Memorial stone for the victims in Bochum- Laer (former cemetery, now Park Dannenbaumstraße)

- Memorial stone for the victims in the cemetery in Bochum- Werne

- Memorial plaques from the 1930s and 1980s on the Steeler Strasse water tower in Essen

- Memorial plaque at the Südwestfriedhof Essen

- Honorary grave and memorial stone for the victims in Haltern am See (in the Haard forest , south of Haltern)

- Honorary grave in the Gelsenkirchen south cemetery

- Honorary grave in the Westfriedhof in Oberhausen

- Honorary grave in the Bottrop-Kirchhellen cemetery

- Memorial for the murdered workers of the Red Ruhr Army in Dortmund on the north cemetery

- Honorary grave in the cemetery in Dinslaken (Flurstrasse)

- Memorial stone on a mass grave in the Haard, Hünxe -Bruckhausen

- Honorary grave in the Duisburg-Walsum cemetery

- Honorary grave with statue on the Remberg cemetery in Hagen

- Commemorative plaque at the train station of the city of Wetter (Ruhr) for the fighting that took place there

- Subsequently furnished “grave” for the workers killed in Wetter as well as a citizen on the area of the buried free corps fighters in the Wetter cemetery

- Honor grave in Bommern

- Memorial plaque in Pelkum at the location of the shootings

- Honorary grave at the Pelkum cemetery

- Honorary grave at the Wiescherhöfen cemetery

- Honorary grave with statue in the Bergkamen cemetery

- Memorial stones for two mass graves in the Haard near Olfen -Eversum

- Memorial stones and plaque on the cemetery of honor at Königshöhe in Wuppertal -Elberfeld

- Honorary grave with memorial plaque for 8 people killed in the city cemetery St. Maximi in Merseburg

"Honor" of Freicorps members and other fighters for the coup.

- A memorial stone erected during the Nazi era for putschists who died in battles with Schleswig workers in front of Gottorf Castle (Schleswig-Holstein State Museum), Schleswig , which was then used as barracks

- Ruhr fighter memorial in Essen from the Nazi era for members of the Freikorps, Reichswehr and police killed in the Ruhr area in 1918-20

- Cenotaph and grave for fallen police officers, Südwest-Friedhof, Essen

- Honorary grave for the fallen of the Loewenfeld Freikorps, Bottrop-Kirchhellen cemetery

- Naming of Loewenfeldstrasse , Bottrop-Kirchhellen

- Graves of honor and memorial plaques

Monument to those who fell in March in Weimar, the sculpture was designed by the architect Walter Gropius in 1921

Memorial to the workers who died in Hennigsdorf during the Kapp Putsch

Memorial stone for the workers who died in the Berlin district of Köpenick during the Kapp Putsch

Honorary grave with statue in the Remberg cemetery in Hagen

1934 inaugurated Ruhr Warrior Memorial in Essen for fallen fighters against the workers in the Ruhr area

Memorial plaque to the Kapp Putsch in Schwerin , Mecklenburger Strasse 4–6

Memorial stone for fallen workers, Futranplatz, Berlin-Köpenick

Memorial to the victims of the Kapp Putsch in the cemetery in Berlin-Adlershof

Cinematic reception

The Bayerische Rundfunk reconstructed in 2011, the events surrounding the Kapp Putsch for the docudrama The counter-revolution - the Kapp Putsch Lüttwitz . Under the direction of Bernd Fischerauer , a. a. Hans Michael Rehberg (General von Lüttwitz), Jürgen Tarrach (Friedrich Ebert) and Michael Rotschopf (Waldemar Pabst). The first broadcast took place on May 20, 2011 in the BR-alpha program .

The Westdeutsche Rundfunk Köln , WDR broadcast the film Eyewitnesses Report on March 9, 1986 : The Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch 1920 (approx. 45 min.) By Claus-Ferdinand Siegfried; scientific advice Dr. Werner Rahn . The following contemporary witnesses can be seen and heard in the film: Hans-Joachim von Stockhausen, ensign; Siegfried Sorge, lieutenant at sea; Herbert Jantzon, lieutenant; Albert Witte, member of the socialist youth workers in Kiel; Axel Eggebrecht , then a student; Max Kutzko, machine gunner in Kiel; Ernst Bästlein, metal worker; Paul Debes, seaman; Karl Marquardt, apprentice carpenter; Axel Blessingh, midshipman; Hans Möller, Ensign; Franz Rubisch, miner's child; Heinrich Köster, miner.

See also

literature

- James Cavallie : Ludendorff and Kapp in Sweden. From the lives of two losers. Lang, Frankfurt [a. a.] 1995, ISBN 3-631-47678-7 (comprehensive treatise on the events in Berlin, the background, the main conspirators, and the events after the coup).

- Johannes Erger : The Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch. A contribution to German domestic politics 1919/1920. Droste, Düsseldorf 1967 (still the standard work on the subject, but the resistance actions, left uprisings, etc. are almost completely absent).

- Gerald D. Feldman : Big Industry and the Kapp Putsch . In: Ders .: From World War I to the Great Depression : Studies on German Economic and Social History 1914–1932 (= Critical Studies on History , 60). V&R, Göttingen 1984, pp. 192-217.

- Klaus Gietinger : Kapp Putsch. 1920 - Defensive battles - Red Ruhr Army . Butterfly, Stuttgart 2020, ISBN 3-89657-177-X .

- Ekkehart P. Guth: The conflict of loyalty of the German officer corps in the revolution 1918-1920 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1983.

- Heinz Hürten : The Kapp Putsch as a turning point. About the framework conditions of the Weimar Republic since the spring of 1920 (= Rheinisch-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften, lectures G 298). West German Verlag, Opladen 1989.

- Erwin Könnemann , Gerhard Schulze (ed.): The Kapp-Lüttwitz-Ludendorff Putsch. Documents. Olzog, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-7892-9355-5 (comprehensive source collection).

- Gabriele Krüger: The Ehrhardt Brigade . Leibniz Verlag, Hamburg 1970.

- Erhard Lucas : March Revolution 1920 , Volume 1–3. Verlag Roter Stern, Frankfurt am Main 1970–1978 (still fundamental, with a focus on the fighting in the Rhine-Ruhr area.).

- Heiner Möllers: "Reichswehr does not shoot at Reichswehr!" Legends about the Kapp-Lüttwitz putsch of March 1920. In: Military history. Journal for Historical Education. Edited by the Military History Research Office , Potsdam, 11, 2001, pp. 53–61.

- Dietrich Orlow : Prussia and the Kapp Putsch . (PDF). In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte , 26, 1978, pp. 191–236.

- Rainer Pöppinghege: Republic in civil war. Kapp Putsch and counter-movement on Ruhr and Lippe in 1919/20 . Ardey-Verlag, Münster 2019 (= compact regional history , vol. 2). ISBN 978-3-87023-443-0 .

- Martin Polzin: Kapp Putsch in Mecklenburg: Junkers and rural proletariat in the revolutionary crisis after the First World War (= publications of the Schwerin State Archives , 5). Hinstorff, Rostock 1966.

- Hans J. Reichardt: Kapp Putsch and general strike in March 1920 in Berlin. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung Beuermann, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-87584-306-1 .

- Hagen Schulze : Freikorps and Republic. 1918-1920. Boldt, Boppard am Rhein 1969.

- Wolfram bet : Gustav Noske. A political biography . Droste, Düsseldorf 1987.

Web links

- Literature on the Kapp Putsch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Battle for the Republic . Federal Agency for Civic Education

- Information on the Kapp Putsch on the website of the German Historical Museum

- Kapp Putsch in Kiel , contemporary witnesses and documents

- Bruno Thoß : Kapp-Lüttwitz-Putsch, 1920 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- When soldiers painted swastikas on their helmets

Individual evidence

- ↑ The military coup in 1920 (Lüttwitz-Kapp-Putsch). Lüttwitz-Kapp-Putsch at the German Historical Museum.

- ↑ See on this Sebastian Haffner: The betrayed revolution 1918/1919. Scherz Verlag, 1969, p. 195 ff.

- ↑ Sebastian Haffner : The betrayed revolution 1918/1919. Scherz, Bern 1969, p. 195.

- ↑ Harold J. Gordon Jr .: The Reichswehr and the Weimar Republic. Verlag für Wehrwesen Bernard & Graefe, Frankfurt am Main 1959, p. 113.

- ^ Haffner: The betrayed revolution 1918/1919. 1969, p. 198.

- ^ Haffner: The betrayed revolution 1918/1919. 1969, p. 201.

- ^ Haffner: The betrayed revolution 1918/1919. 1969, p. 202.

- ↑ Uwe Klußmann, DER SPIEGEL: "There is no pardon at all" - DER SPIEGEL - history. Retrieved March 13, 2020 .

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: Weimar 1918–1933. Beck, 1993, p. 121.

- ^ Gordon A. Craig : Deutsche Geschichte 1866-1945. P. 376.

- ↑ Axel Weipert: The Second Revolution. Berlin council movement 1919/1920 . Bebra Verlag, Berlin 2015, pp. 190–234.

- ^ Arnd Krüger & Rolf Pfeiffer: Theodor Lewald and the instrumentalization of physical exercises and sport. Uwe Wick & Andreas Höfer (eds.): Willibald Gebhardt and his successors (= series of publications by the Willibald Gebhardt Institute, vol. 14). Aachen: Meyer & Meyer 2012, pp. 120–145, ISBN 978-3-89899-723-2 .

- ↑ Ursula Büttner: Weimar - the overwhelmed republic 1918–1933. In: Gebhardt (Hrsg.): Handbuch der deutschen Geschichte, Stuttgart 10th ed. 2001 (Volume 18), pp. 173–714, here p. 371.

- ^ Siegfried Schindelmeiser: The history of the Corps Baltia II zu Königsberg i. Pr. , Vol. 2, ed. by Rüdiger Döhler and Georg v. Klitzing, Munich 2010, p. 548.

- ↑ Kapp Putsch Memorial at wiki.hv-her-wan.de, accessed on May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Former mass grave Kapp Putsch, Südwest-Friedhof Essen on ruhr1920.de, accessed on May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Bruckhausen mass grave at ruhr1920.de, accessed on May 2, 2020.

- ↑ Thea A. Struchtemeier: "From weather went the weather!" - Reminiscence of the history of the creation of the workers' memorial plaque to commemorate the suppression of the Kapp Putsch in March 1920. In: 1999, Zeitschrift für die Sozialgeschichte des 20. und 21st century. Volume 6, January 1991, issue 1, pp. 161 ff.

- ↑ The counter-revolution - the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch . In: BR-alpha . May 20, 2011.

- ^ Counterrevolution: The Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch 1920 on YouTube (the whole film, 90 minutes).