Gottorf Castle

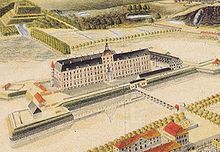

Gottorf Castle ( Low German : Slott Gottorp , Danish : Gottorp Slot ) in Schleswig is one of the most important secular buildings in Schleswig-Holstein . In its more than eight hundred year history it has been rebuilt and expanded several times, so that it changed from a medieval castle to a Renaissance fortress to a baroque palace . It gave its name to the ducal house of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf , from which four Swedish kings and several Russian tsars, among others, came from in the 18th century emerged.

The largest castle in the state was owned by the Danish royal family and the dukes of Schleswig. After the annexation of Gottorfer proportion of the Duchy of Schleswig by Denmark in 1713, the castle served as the seat of the Danish governor in Schleswig, then it was used as barracks. Today it houses two Schleswig-Holstein state museums and the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation at Gottorf Castle . To the north of the palace, the Neuwerkgarten , one of the first baroque terrace gardens in Northern Europe, has been reconstructed in recent years .

historical overview

Middle Ages to modern times: From the moated castle to the royal palace

Today's castle on the castle island at the end of the Schlei had several previous structures that originally served to guard a narrow country lane. Bounded by the Schlei in the east and the then swampy Treenen lowlands in the west, there was only a narrow land bridge through the Jutian peninsula at the height of the old Danewerk . This was easy to control from the castle built here. In the Middle Ages, Gottorf was referred to as the “key and watch of all Denmark”. This points to the protective function of the castle as a defensive and guard post in the border area as well as to its importance as a place of trade and diplomacy - the keys to a peaceful exchange with the northern kingdom.

Gottorf Castle was first mentioned around 1161. It was built under Bishop Occo and also served as a fortress for the bishops from nearby Schleswig after an older, northwestern refuge on the site of today's Falkenberg estate was destroyed after a Danish attack. In 1268 the complex was sold to the Counts of Schauenburg in an exchange deal and in the period that followed it was repeatedly targeted by Danish attacks, all of which, however, could be repelled.

Because Adolf VIII remained childless and his brother's children also died early , the Treaty of Ripen in 1459 regulated that the inheritance should pass to Adolf's nephew, the Danish King Christian I. Gottorf came into the possession of the crown and served as the residence and administrative seat of the Danish kingdom, which in this epoch stretched from the Danish heartland, which at that time also comprised the southern Swedish provinces of Skåne, Halland and Blekinge, via the duchy of Schleswig, and to Norway extended. In 1492 a fire destroyed large parts of the medieval castle, which was then renovated and modernized in several stages. Christian's successor Friedrich I, for example, had the west wing built in the style of the Nordic early Renaissance as the first modern building of the palace around 1530 , which was the first Renaissance building north of the Elbe. Friedrich I resided almost exclusively in Gottorf, and the Danish historian Arild Huitfeldt described him as an old hen that was reluctant to leave its nest.

16th and 17th centuries: residence of the Gottorf dukes

After Friedrich's son Christian III. had acceded to the throne, his half-brother Adolf I received scattered areas in Schleswig and Holstein as an inheritance and thus founded the Duchy of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf in 1544 . Gottorf Castle became the main residence and eponymous for the line. On New Year's Eve 1564/65, another fire disaster struck the castle and as a result it was expanded into a four-wing fortress in different construction steps. From Duke Adolf's lively building activity, the north wing on Gottorf has been preserved; other buildings belonging to his rule included the side residences of Husum and Reinbek . The administration of the duchies at that time was almost completely split up into the Gottorf parts ruled by the Schleswig dukes, the royal parts ruled by the Danish royal house and mostly administered by governors, and the property districts ruled by both lines . As the seat of the administration of the ducal portion, the Gottorf Castle grew into the largest castle complex in Schleswig and Holstein. In its heyday, the court consisted of more than 400 people.

Under Duke Friedrich III. Gottorf developed into a center of science and culture and thus one of the most important royal courts of the era. The Gottorf giant globe in the Neuwerkgarten, the library and the art chamber were famous far and wide. As a court mathematician and librarian, the polymath Adam Olearius was instrumental in these projects. Olearius accompanied as secretary 1636–1638 that of Friedrich III. Persian embassy sent to Isfahan in Persia , where new trade contacts were to be established. From an economic point of view, the expedition was unsuccessful, but it had important cultural consequences, according to Olearius' Persian travel description, first published in 1646 . For example, the globe house was built according to Olearius' designs in the Persian style. The court scholar also looked after and enlarged the library and the art chamber. The collection of the Dutch doctor Bernhard Paludanus , acquired in 1651, formed the basis of the Gottorf Kunstkammer . The painter Jürgen Ovens , who created numerous paintings as well as room-filling painting series for the castle and its facilities and acted as a broker in the Netherlands, was still one of the important actors of the Gottorf heyday . The Duke ran a chemical laboratory under the direction of Joel Langelott . Friedrich's son Christian Albrecht continued his father's ambitions and had Gottorf Palace and its collections expanded.

Thanks to a controlled marriage policy, the Gottorf family was connected to other princely houses in northern Europe. In the course of the 17th century, the ties to the powerful Kingdom of Sweden became ever closer, especially through the marriage of the Gottorf Princess Hedwig Eleonora to Karl X. Gustav of Sweden . The relationship with Denmark, however, deteriorated increasingly, despite attempts at rapprochement such as the marriage of Christian Albrechts and Friederike Amalies of Denmark . The increasingly demanded sovereignty of the Gottorf house snubbed the Danish crown and culminated in multiple occupations of the duchy.

The now outdated Renaissance fortress no longer corresponded to the representative ideas of the time at the end of the 17th century and Duke Friedrich IV commissioned a baroque extension of the complex. The castle was built from 1697 to 1703 based on designs by the Swedish builder Nicodemus Tessin the Elder. J. redesigned and enlarged. However, Friedrich IV died during the Great Northern War that broke out at the beginning of the 18th century on the battlefield near Klissow and did not experience the conversion into a large baroque residence. By the time he died, only the massive south wing was completed, and further planning came to a standstill due to the events that followed. During the war, the Gottorf Duchy sided with the Kingdom of Sweden, both because of the family ties to Sweden and because the dukes hoped to break away from Denmark. After Sweden experienced a defeat in 1713, the Gottorf dukes were ousted by the Danish royal family and their lands in Schleswig were occupied.

18th and 19th centuries: Gottorf as the seat of the Danish governors

The annexation of the former Gottorf parts of the Duchy of Schleswig was declared lawful in the Peace of Frederiksborg in 1720 . 1721 took place in the castle, the homage of the Danish king by the knighthood. Only the Gottorf shares in the southern Duchy of Holstein remained in the possession of the Gottorf family and were ruled from then on by Duke Karl Friedrich from Kiel Castle . Although the city of Schleswig remained one of the most important places in the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, the sole lord of the Duchy of Schleswig was now the king in Copenhagen and Gottorf was only one of many castles in his empire. The Danish crown showed no interest in the palace complex, which is located far from the capital. A large part of the movable furniture and the art chamber were moved to Copenhagen and transferred to other residences there. The extensive library with over 10,000 volumes came to the Danish Royal Library in 1749 .

Gottorf was converted into the seat of the Danish governors , although it was considerably oversized for this new purpose. From 1731 it served as the residence for the governor Friedrich Ernst von Brandenburg-Kulmbach , who soon preferred the Friedrichsruh Palace , which was newly built for him . In 1768 the Gottorf Treaty was negotiated at the castle, releasing the city of Hamburg from formal Danish sovereignty. The palace experienced its last heyday under the governor Karl von Hessen-Kassel , who administered the duchies from 1768 to 1836. Under the Landgrave, the court still consisted of more than 100 people and in the area around the Schlei, Louisenlund and Carlsburg, two smaller secondary residences were built. During this time, the future Danish King Christian IX was born in 1818 . , the father-in-law of Europe , was born in Gottorf.

19th and 20th centuries: barracks and wars

After the war of 1848 , the Danes first set up a hospital and then a barracks in the castle so that they could take action against the rebels in Schleswig-Holstein more effectively from here. The building was adapted to the new needs and the interiors lost much of their once important features. The former parade rooms and ducal rooms have been converted into dormitories and dining rooms. The outbuildings were demolished and instead extensive stables were built, and the defenses razed. Gottorf remained barracks when it went to Prussia as a result of the Second Schleswig War in 1867 and retained this function until 1945.

The building survived the world wars without war-related destruction, but the south and west wings were badly damaged in a fire in 1917. In the course of the Kapp Putsch , the castle was occupied by putschists in 1920, and ten people were killed in subsequent fighting.

At the beginning of 1945 more and more refugees from the eastern areas of the German Reich arrived in Schleswig, the number of which rose to almost 18,000 by the summer. Like many residences in the country, Gottorf was used as a temporary reception camp and several hundred refugees were housed in the castle. In the post-war period, the entire facility was made available to the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums from 1948.

Current use: the museums

The castle houses the most important museums in Schleswig-Holstein and is involved in a large number of cultural events. In addition to changing exhibitions (including contemporary artists), theater performances and concerts take place in the courtyard at irregular intervals.

The entire area and a large number of the interior rooms are accessible to visitors. Part of the original furnishings of the castle has been preserved and can be viewed as part of the museum tours. Particularly noteworthy are the festive deer hall from 1591 and the two-storey Renaissance chapel. The castle is considered to be the most important secular building in the state of Schleswig-Holstein.

State Museum for Art and Cultural History

The State Museum for Art and Cultural History has been housed in Gottorf Castle since 1945. Its important collections range from the high Middle Ages to modern times and contemporary art.

State Archaeological Museum

The collections of the State Archaeological Museum with over three million finds lead through the history of Northern Europe from the Stone Age to the High Middle Ages. They are among the largest collections of their kind in Europe. The museum was founded in 1836 from the merged holdings of the former Museum of Patriotic Antiquities in Kiel and the Flensburg Collection (Flensborgsamlingen) Helvig Conrad Engelhardts . The oldest objects were made from stone by Neanderthals around 120,000 years ago . Flint tools, weapons and ceramics bear witness to the long journey of man from the hunters and gatherers of the Paleolithic to the farmers of the Neolithic.

Some of the most valuable objects are vessels made of gold, daggers and swords made of bronze, as well as jewelry and utensils such as the Meldorf fibula . Approximately 30,000 grave finds are known from the Iron Age in Schleswig-Holstein. Investigations on the graves allow for the first time a more precise picture of the structure of society in present-day Schleswig-Holstein in the centuries around the turn of the times. The most famous exhibits in the museum include the bog bodies , such as the Windeby bog body and the Windeby man .

In the Nydamhalle , the former drill hall next to the west wing of the castle, located since the end of World War II, an exhibit of international importance: the 23-meter-long, in Nydam Mose in Sonderborg found Nydam ship , which was built around 320 AD... It was relocated from Kiel during the war and has remained in Schleswig ever since. The boat, a unique artefact from late antiquity , was unsuccessfully reclaimed by the Danish side after the First and Second World Wars. In May 2013, on the occasion of its discovery 150 years ago, the State Museum presented an exhibition about the history and significance of the exhibit. The ancient finds from the Thorsberger Moor and the Nydam Moor from the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, which were shown in the Nydamhalle until then , have been presented in the castle since then. These finds are among the most impressive archaeological evidence in the country and Northern Europe. Military equipment, harness, everyday equipment and clothing paint a clear picture of the Teutons of the north.

The exhibition Village - Castle - Church - City shows archaeological finds on the history of Schleswig-Holstein in the Middle Ages. Since 1995, the State Archaeological Museum has also included the ethnological collections of the University of Kiel. The exhibition will include exhibitions on the Japanese Samurai and the northern European nation of seeds .

Branch offices

Other museums in Schleswig, Büdelsdorf and Rendsburg as well as the Viking Museum Haithabu and the Cismar Monastery are managed as branches by the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation located in the castle . The former folklore equipment collection of the State Museum moved to its own museum building in 1995. The Folklore Museum Schleswig was until 2014 a few blocks from Gottorf Castle located on the Schleswig Hesterberg , not far from the house and globe Baroque garden. After the Molfsee open-air museum was accepted into the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation, it merged with the Folklore Museum in Schleswig, which was then closed. The old museum location on the Hesterberg is currently being converted into a central depot of the foundation, while the Jahr100Haus, an exhibition building that also serves as an entrance building, was built in Molfsee near Kiel and opened in 2021 for the exhibitions of the Folklore Museum.

Buildings

The castle building

The castle grew from a large number of individual construction phases to its present form. Individual parts of the building were repeatedly expanded and expanded or demolished and renewed. A splendid Renaissance fortress slowly developed from the first castle, some of which were still solitary, and at the end of the 17th century it was partially redesigned into a large baroque residence.

The castle forms an irregular four-wing complex around a courtyard; the floor plan resembles a large P. The current shape of the building with partly very sober wall surfaces on the northern buildings and in the room lines is due to the renovation work of the 19th century, after which the castle was only used as a barracks.

The west wing

The west wing was built from 1530, the work was interrupted by the count feud and completed around 1538. Today it forms the oldest visible building stock of the castle, originally it was a free-standing structure, which was only connected to the other buildings in the course of the castle extensions. The west wing once consisted of four single houses connected lengthways , which, like in Glücksburg Castle , were typical of courtly architecture of the Renaissance period in Schleswig and Holstein. The courtyard facades of the west wing were originally gabled, the now sandstone-colored surfaces of the walls were whitewashed and the decorative elements were provided with contrasting colors. The once most magnificent building of the fortress has been simplified several times since the 19th century and the once numerous building details have been gradually removed. The facade as it currently appears is the result of a reconstruction from the end of the 20th century. The wing once contained the living quarters of the Danish king , the tower-like bay window to the inner courtyard , known as a lantern , contained small writing rooms . The current bay is a reconstruction; the original was destroyed in 1872 by an explosion of the powder stored there.

After the building began to sink due to a troubled subsoil, the outer wall was secured with the supporting pillars that have been preserved to this day . The individual gable roofs were removed in the 19th century and replaced with a large, contiguous roof area. The transition from the medieval building to the more modern south wing can be seen on the outer facade of the west wing.

The defense tower , which marks the outer angle between the west and north wings, dates back to 1540. The building was formerly a free-standing defense tower of the earlier castle. Originally not conceived as a residential tower, it was only connected to the palace in the course of constant expansion. Since the basement of the tower of the neighboring kitchen in the north wing was used for meat preparation, it was also known as the butcher's tower .

The north wing

The oldest components are now under the north wing, some of which still rests on the walls and foundations of the first castle. The north wing itself dates from the late 16th century and was designed by Herzog I. Adolf commissioned. The building is younger than the west wing and was also more modern at the time.

The rows of gables facing the courtyard and the garden side were once decorated with splendid Renaissance decorations. Today, for example, the similarly designed gables of Ahrensburg Castle offer an idea of their earlier shape . Ornate Renaissance portals and a fountain from the time of Christian III have been placed in the courtyard facade of the north wing . receive. The extensive garden facade of the building in the direction of the new plant is almost unadorned today. Between the rows of windows are wide pillars spanning several floors , which once contained the steps from the various floors.

The castle's best-preserved rooms are in the north wing. Noteworthy are the White Hall and the Blue Hall , which are decorated with fine stucco , as well as the festive deer hall decorated with hunting motifs . The palace chapel has also been in the north wing since 1590. The splendidly furnished room was designed based on the model of the chapel in Sonderburger Castle and has been preserved almost unchanged since the Renaissance. An important showpiece is the prayer chair, a lavishly furnished, heatable box for the lords of the castle with paneling , which was installed above the altar in 1612. The prayer chair and the deer hall were extensively restored from 2006 to 2007.

The east wing

The east wing is the palace's smallest wing. It forms the connection between the south and north wings and consists of two parts of the building dating from 1564 to 1565. As in the north wing, the foundations of the former castle are still hidden here. Towards the courtyard, which was once provided with open arcades , a stair tower from 1664 has been preserved. The remains of a hypocaust system were found inside the building .

The former architectural decoration of the east wing was almost completely removed during the barracks period, so that especially the northern outer wall of the building together with the wall surface of the north wing makes a somewhat disordered impression on today's observer.

The south wing

The south wing offers the most famous view of the largest castle in Schleswig-Holstein. Today's access via the castle courtyard was provided with a gatehouse and a gallery building until the 17th century, which stylistically corresponded to the Renaissance castle of that time. Today's central tower of the main facade was the southeastern and largest corner tower of the palace complex during the time of the castle.

Duke Christian Albrecht was already planning a redesign of the palace and had Nicodemus Tessin the Elder commissioned him. J. advise. He had stayed at the castle repeatedly from 1687 to 1692. The renovations did not begin until 1697 under Duke Friedrich IV. Domenico Pelli took over the construction management, the executive architect was the court architect Johann Hinrich Böhme , who was based on Ticino's designs. The Swedish influence is unmistakable, the building proportions are similar to Vadstena Castle , for example, and the austere facades can be found on Stockholm Castle , also a work of Ticino.

Most of the old structure of the south wing was laid down and the new building was expanded to almost double its size. The work proceeded in two sections, the left half above the old building was completed first, the right, new wing, then. On the ground floor of the building, an important Gothic hall from an earlier construction phase has been preserved - the so-called King's Hall - in which the library and the art chamber of the palace were located in the 17th century.

The courtyard area was reduced and the courtyard facade of the south wing was preceded by large corridors, which additionally connected the new en filade rooms. Both were innovations in the castle, which until then had only been expanded as required and therefore had a very irregular floor plan and hardly any structural order. The former corner tower was transformed into a tower-like central projection with the main portal. A contemporary, spacious staircase was installed in the tower, which was changed beyond recognition during the renovation work to the barracks in the 19th century. The facade was given symmetrical rows of windows in the Baroque style . The first mezzanine floor , with round windows, was intended for administration and servants' rooms ; on the second floor above is the actual bel étage with the Duke's rooms, the windows of which are decorated with segmented gables over the entire width of the facade . The top floor was intended for the Duchess' suite of rooms. After completion, the building was originally painted a bright red and the architectural details gray. The building was painted white today at the end of the 18th century.

The size of the south wing towers over the almost rectangular base of the former fortress. On its protruding back there is a windowless wall surface, which was probably initially undesigned as a transition to a new east wing. However, the events of 1713 put an end to further building projects.

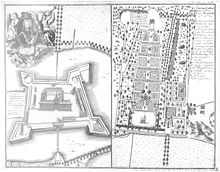

The castle island

The castle island is of natural origin, the castle lake that surrounds it was connected to the Schlei until 1582 , but was then separated from it by a dam. The island had fortified walls since the Middle Ages and in the Renaissance it was given a shield made of mighty ramparts , which were protected by four bastions at the corners. Some of the building material came from Schleswig churches, which were demolished during the Reformation . A dam connected the island with the gardens outside the fortress grounds. The fortifications were demolished from 1842, and the earth masses of the ramparts were used to enlarge the area of the island.

To the east of the castle were the extensive stables designed in the form of a double house for the horses and carriages of the ducal family and other dignitaries. Several hundred animals were once cared for here. There were other stable buildings for lower-ranking members of the court outside of the castle island near the old garden , which the street name Herrenstall is reminiscent of to this day . The island also had a ballroom and an enclosure where bears were displayed.

There are still a large number of outbuildings on the castle island. The former coach houses and riding arenas that can be seen today all date from the barracks era of the castle. They are used by the island's museum facilities. Opposite the main portal are a guard house and a detention house, which have housed the museum cash desk and the souvenir shop. South of the main facade is the commandant's house, a building from the beginning of the 20th century that served as the residence of the commanders of the barracks.

Gardens

The Neuwerkgarten and the Globushaus

A 300 meter long avenue, located on a dam, leads from the castle through the castle lake to a small cascade decorated with temples and dolphins . The adjoining Neuwerkgarten at Gottorf Castle is the first baroque terrace garden north of the Alps. The “new work”, the youngest of the green spaces that once surrounded the palace, could only be admired in fragments for a long time. From 1984 the restoration of the gardens began with the restoration of the small cascade complex. In 1991 the first park maintenance work for a historic garden in Schleswig-Holstein was created, edited by Rose and Gustav Wörner, who prepared the further development of the restoration of the garden and could be raised with EU funds. The re-erection of the replica of the Hercules Group in the summer of 1997 in the middle of the Hercules pond excavated two years earlier represented the first high point of the conservation efforts.

The 300 or so rubble of the Hercules group on the bottom of the pond, partly cyclopean shape and size, partly crumbled and barely identifiable, was recovered, poured and put together in 1994 using archaeological methods. Subsequently, in 2001 the Königsallee in Gottorfer Neuwerkgarten could be replanted with donations. Grants from the German Foundation for Monument Protection enabled the archaeological excavation and documentation of the terraces from 2003 to 2004. After completion of the globe house, the terraces could be newly laid out and planted according to historical models. Today nothing can be seen of the once extensive sculptures on the terraces of the Neuwerkgarten. The official reopening of the terraces of the palace gardens took place in August 2007. The Neuwerk is thus the only freely accessible garden in the original Baroque design in Schleswig-Holstein. In 2008 he was the focus of the state horticultural show .

The garden was from 1637 on behalf of Duke Friedrich III. laid out in the style of Roman terraced gardens outside the former fortifications. The name Neuwerk is explained by the contrast to the old gardens in the Friedrichsberg district . The Neuwerk was famous for its variety of plants and some exotic plants, including citrus fruits, aloes and pineapples , which were first cultivated in Northern Europe. The more than 1000 different plant species were cataloged in the Gottorf Codex by the Hamburg flower painter Hans Simon Holtzbecker , probably because Friedrich III and his court scholar Adam Olearius wanted to develop a botanical taxonomy that the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné succeeded in doing in the 18th century . The main features of the garden existed until the 19th century. After the maintenance of the terraces had been neglected in the 18th century, the area eventually overgrown. Only a few historical garden plants survived these times. In the Prussian period , when the castle served as barracks, the garden was then leveled and the area was used as a drill and riding arena.

Since 2005, the center of the Neuwerkgarten has again been adorned with a new globe house , in which a replica of the famous Gottorf giant globe can be seen. The old globe house, once known as Friedrichsburg, was a multi-storey pavilion in what was then the idea of the “Persian style”. This was a reference to the hoped-for trade relations with the Orient, which under Adam Olearius could be planned but not realized. At that time, the globe was considered a kind of eighth wonder of the world ; a large, walkable sphere with the known parts of the world on the outer shell and the sky inside. The virtual "Welt- und Himmelstheater" came into the possession of Peter the Great in 1714, in 1941 it was seized by art protection officers of the Wehrmacht in the palace district outside Leningrad and brought to Germany. In 1946 it was returned to the Soviets as spoils of war .

Holtzbecker's plant atlas provided the starting point for the historical planting of the garden, of which around 1200 species have survived even after 250 years of inadequate maintenance. The actual terrace garden rises behind the globe house and consists of several levels planted with flower beds and box tree ornaments. The large terrace steps are slightly angled and slightly tapered towards the rear . This peculiarity makes the terrace garden appear even larger and longer, an illusion that is typical of baroque garden architecture. The outside stairs of the terrace areas are also decorated with cascades. Looking towards the castle, there is a large water basin, the so-called mirror pond, in front of the terrace steps . In the middle is a figure depicting the battle of Hercules with the Hydra . After the garden had been neglected more and more in the 18th and 19th centuries, the sculpture finally fell from its base and sank into the boggy pond. The remains made a picturesque impression for many years.

Above the garden, on the last level, there was once a pleasure palace called Amalienburg as a point de vue . The castle was built in 1660 by Duke Christian Albrecht for his wife Friederike Amalie of Denmark . The Amalienburg was demolished in 1826 because it was in disrepair. To the west of it was the building of the orangery, which had also been demolished . The garden table of the State Office for the Preservation of Monuments in Schleswig-Holstein offers a good overview of the Neuwerkgarten.

The lost gardens

The castle was formerly surrounded by other gardens. To the south of the castle island was the so-called Westergarten , which was laid out in the 16th century under Duke Adolf. From 1623 to 1637 the old garden , which protrudes into the Schlei , was built east of the castle, in the direction of the Wikingturm . For its facility, Duke Friedrich III won. the gardener Johannes Clodius (1584–1660). In the 18th century the garden was only used as a kitchen garden and also contained several fish ponds. Today only the street name "Alter Garten" reminds of this formally designed green area. Immediately after this garden, the new plant was created from 1637 , a terrace garden north of the palace, also by Johannes Clodius. From 1707 the Palais Dernath with a French baroque garden, designed by Johann Christian Lewon (around 1690–1760) , was built on the grounds of the Westergarten . In place of the palace that burned down in 1868, the Schleswig-Holstein Higher Regional Court rises, also known as the “Red Elephant” by the population. The building was built between 1875 and 1878 according to plans by the master builder PEP Köhler.

Extensive hunting areas belonged to the castle. Significantly, you can see the hunting area formerly known as the zoo , which is now part of a forest, from the north windows of the deer room .

literature

sorted alphabetically by author

- Karen Asmussen-Stratmann: The new work of Gottorf. A north German garden from the 17th century . In: Die Gartenkunst 14 (1/2002), pp. 73–80.

- Adrian von Buttlar , Margita Marion Meyer (ed.): Historical gardens in Schleswig-Holstein. 2nd Edition. Boyens & Co., Heide 1998, ISBN 3-8042-0790-1 , pp. 533-566.

- Georg Dehio : Handbook of the German art monuments . Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein . 3rd revised and updated edition, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-422-03120-3 , pp. 859–873.

- Herwig Guratzsch (ed.): The new Gottorfer globe . Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7338-0328-0 .

- Henning von Rumohr : Castles and mansions in the Duchy of Schleswig. A manual . Full paperback edition. Droemer Knaur, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-426-04412-9 .

- Ernst Schlee : Gottorf Castle in Schleswig . (= Art in Schleswig-Holstein 15). Wolff, Flensburg 1965.

- Heinz Spielmann , Jan Drees (ed.): Gottorf in the splendor of the baroque. Renaissance and Baroque. , Vol. 3 of the exhibition catalogs Gottorf in the splendor of the baroque. Schleswig 1997.

- Antje Wendt: Gottorf Castle . (= Castles, palaces and fortifications in Central Europe 5). Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7954-1244-7 .

- Anja Silke Wiesinger: Gottorf Castle in Schleswig- The south wing, studies on the baroque redesign of a north German residence around 1700. Ludwig Verlag, Kiel 2015, ISBN 978-3-86935-249-7 .

- Carsten Fleischhauer: A carriage for the Olympics - On the history of the state museum since 1878. In: Kirsten Baumann, Gabriele Wachholtz (ed.): Best friends. Artwork for Gottorf Castle. Schleswig 2016, pp. 18–35.

- Mario Titze: Johann Heinrich Böhm the Elder J. from Schneeberg - "Distinguished Sculptor Zu Dreßden". In: Die Dresdner Frauenkirche , Jahrbuch 24 (2020), Schnell + Steiner, Regensburg 2020, ISBN 978-3-7954-3571-4 , pp. 105–146.

Web links

- Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation Gottorf Castle

- Museums in Schleswig-Holstein - Gottorf

- The castle in the Schleswig-Holstein state portal

- Detailed information about the Neuwerk garden

- Art historical project to explore the Amalienburg

- Virtual tour of the globe, globe house and baroque garden

- Reconstruction drawing as it was in the 17th century

- Illustration by Daniel Meisner from 1626: Schleswick . Domus amica domus optima ( digitized version )

- Publications on Gottorf Castle in the catalog of the German National Library

- Search for Schloss Gottorf In: German Digital Library

-

Search for Schloss Gottorf in the online catalog of the Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage . Attention : The database has changed; please check result and

SBB=1set

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 800.

- ^ Hans and Doris Maresch: Schleswig-Holstein's castles, manors and palaces . Husum Verlag, Husum 2006, p. 163

- ↑ a b Thorsten Dahl: History of Schleswig in numbers ( Memento from May 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b c d e Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 801.

- ^ CR Rasmussen, E. Imberger, D. Lohmeier, I. Mommsen "The princes of the country - dukes and counts of Schleswig-Holstein and Lauenburg" , page 84. Wachholtz Verlag, 2008

- ↑ Antje Wendt: Das Schloss Gottorf , p. 37

- ↑ a b c Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 812.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 802.

- ↑ Adam Olearius: Increased new description of the Muscowitischen and Persian Reyse . In: Dieter Lohmeier (Hrsg.): Deutsche Neudrucke, Barock series . tape 21 . Tübingen 1971.

- ↑ Chapter "Adam Olearius and the Gottorfer Culture" . In: Kirsten Baumann / Constanze Köster / Uta Kuhl (eds.): Adam Olearius. Curiosity as a method (proceedings for the international conference "The Gottorf court scholar Adam Olearius. Curiosity as a method?", Schleswig 2015) . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-7319-0551-6 , p. 173 ff .

- ↑ Constanze Köster: Jürgen Ovens (1623–1678). Painter in Schleswig-Holstein and Amsterdam . In: Studies on the international history of architecture and art . tape 147 . Michael Imhof Verlag, Petersberg 2017, ISBN 978-3-7319-0369-7 , p. 53 ff., 169 f., 173 ff .

- ↑ a b c d Henning von Rumohr: Mansions and castles in Schleswig , page 162.

- ↑ a b Henning von Rumohr: Mansions and castles in Schleswig , page 161.

- ↑ See Karen Skovgaard-Petersen: Gottorp books in the Royal Library of Copenhagen. In: Ulrich Kuder et al. (Ed.): The library of the Gottorf dukes. Nordhausen: Bautz 2008, ISBN 3-88309-459-5 , pp. 129-145.

- ^ Henning von Rumohr: Schlösser in Schleswig , Knaur 1968, p. 164

- ^ Henning von Rumohr: Schlösser in Schleswig , Knaur 1968, p. 166, 167

- ↑ Henning of fame ear mansions in Schleswig , p 149

- ↑ Reinhardt Hootz (Ed.) Picture Handbook of German Art Monuments - Hamburg-Schleswig-Holstein Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1981, p. 420

- ^ Schloss Gottorf: State Museum for Art and Cultural History

- ↑ Gottorf Castle: State Archaeological Museum

- ↑ Karsten Kjer Michaelsen: Politics bog om Danmarks oldtid. Politiken, Copenhagen 2002, ISBN 87-567-6458-8 (Politikens håndbøger) , p. 138

- ↑ a b Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 804.

- ↑ Antje Wendt: Das Schloss Gottorf , p. 36

- ↑ Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 808.

- ↑ Page no longer available , search in web archives: Report from NDR Online from November 14, 2007 on the occasion of the reopening in December 2007

- ↑ Antje Wendt: Das Schloss Gottorf , pp. 21, 22

- ↑ The Neuwerkgarten on gartenrouten-sh.de

- ↑ Holger Behling, Michael Paarmann: Splendor and misery of the prince garden. (= Monuments in danger , published by the State Office for Monument Preservation Schleswig-Holstein. 5/1985), Kiel 1985, p. 10.

- ↑ Gustav Wörner, Rose Wörner: Explanations of the garden monument maintenance report Schloss Gottorf in Schleswig. Prince Garden and Castle Island. Kiel 1991. The report can be viewed at the Schleswig-Holstein State Office for Monument Preservation in Kiel.

- ↑ Heiko KL Schulze: The Gottorfer Hercules. In: Monument. Journal for the preservation of monuments in Schleswig-Holstein. 2/1995, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 12-20.

- ^ Margita Marion Meyer .: The Gottorfer Fürstengarten in Schleswig . In: The garden art of the baroque . A conference of the German National Committee of ICOMOS in cooperation with the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation and the Working Group on Historic Gardens of the German Society for Garden Art and Landscape Care e. V. Seehof Castle near Bamberg 12.-16. Sept. 1997 (= workbooks of the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation, Volume 103), Munich 1999, pp. 101-107, here pp. 106f.

- ↑ Johannes Habich : To restore the baroque prince garden of Schloss Gottorf zu Schleswig and to reconstruct the monumental Hercules group. In: Die Denkmalpflege, 55 Vol., 1997, Issue 1, pp. 16–48.

- ^ Margita Marion Meyer: The Königsallee in the Gottorfer Neuwerkgarten in Schleswig. In: Monument. Journal for the preservation of monuments in Schleswig-Holstein. 8/2001, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 46-48.

- ↑ Hans Joachim Kühn, Nina Lau: Archaeological research of the Gottorfer baroque garden. , ed. by the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation Gottorf Castle, Wachholtz-Verlag, Schleswig 2006, ISBN 3-529-01799-X .

- ↑ Jörgen Ringenberg: On the planting of the globe garden of Gottorf Castle. In: Monument. Journal for the preservation of monuments in Schleswig-Holstein. 13/2006, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 49-56.

- ^ Michael Paarmann: Schleswig: The sculpture equipment of the Neuwerk garden. In: Adrian von Buttlar , Margita Marion Meyer (ed.): Historical gardens in Schleswig-Holstein, 2nd edition, Heide 1996, pp. 552–555.

- ↑ The baroque garden of Gottorf Castle is part of the State Garden Show 2008 Schleswig-Schleiregion - SH news agency from September 25, 2007 ( Memento from October 23, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Thomas Messerschmidt: Schleswig: Gardens of the Gottorf Residence. In: Adrian von Buttlar , Margita Marion Meyer (ed.): Historical gardens in Schleswig-Holstein, 2nd edition, Heide 1996, pp. 533-545.

- ^ Christian Jensen: Schleswig and surroundings. A guide with a map of the city and the wood . Schleswig 1905, p. 27 .

- ↑ Helga de Cuveland: The Gottorfer Codex by Hans Simon Holtzbecker (sources and research on garden art, vol. 14) Worms 1989.

- ↑ Annick Garniel, Ulrich Mierwald: Stink plants of the Gottorfer Neuwerkgarten in Schleswig - silent witnesses of the past garden splendor. In: Monument. Journal for the preservation of monuments in Schleswig-Holstein. 8/2001, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 49-54.

- ↑ a b c Dehio: Handbook of German Art Monuments. Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein , page 813.

- ↑ Ulrich Schneider: The new globe house in the baroque garden of Gottorf Castle. In: Monument. Journal for the preservation of monuments in Schleswig-Holstein. 13/2006, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 57-63.

- ↑ Henning of fame ear mansions in Schleswig , p 160

- ↑ - Introduction. Retrieved July 12, 2021 .

- ↑ Neuwerkgarten Schloss Gottorf. Garden boards of the State Office for Monument Preservation Schleswig-Holstein (PDF; 104 kB)

- ↑ Michael Paarmann: Gottorfer Gartenkunst - The Old Garden. Dissertation at the Art History Institute of the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel 1986.

- ↑ a b Asmussen-Stratmann, p. 73.

- ↑ Antje Wendt: Das Schloss Gottorf , pp. 54, 55.

- ↑ Gisela Thietje: Schleswig Palais Dernath. In: Adrian von Buttlar , Margita Marion Meyer (ed.): Historical gardens in Schleswig-Holstein. 2nd Edition. Boyens & Co., Heide 1998, ISBN 3-8042-0790-1 , pp. 563-566.

- ↑ The Higher Regional Court: On the history of the building. In: Schleswig-Holstein.de .

- ↑ Georg Dehio : Handbook of German Art Monuments . Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein . 3rd revised and updated edition, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-422-03120-3 , pp. 873–874.

Coordinates: 54 ° 30 ′ 42 ″ N , 9 ° 32 ′ 29 ″ E