Peter the Great

Peter I, the Great ( Russian Пётр I Вели́кий , transcribed Pjotr I Velíkij ), born as Pjotr Alexejewitsch Romanow (Russian Пётр Алексе́евич Рома́нов ; * May 30th July / 9th June 1672 in Moscow July 28th / 9th June 1672 greg July / 8th February 1725 greg. in Saint Petersburg ), was Tsar and Grand Duke of Russia from 1682 to 1721 and the first emperor of the Russian Empire from 1721 to 1725 . He is considered one of the most important rulers of Russia. The nickname The Great refers to his achievements, but his height was also appropriate: According to contemporary information, Tsar Peter was actually a giant in stature. Different sources give dimensions between 2.01 and 2.15 meters.

Life

Peter was born on June 9, 1672 in the Moscow Kremlin . The father of the future emperor of Russia, Alexei Mikhailovich , had numerous descendants, including Peter as a fourteenth child. Peter's mother was the second wife of Alexei Mikhailovich, Natalia Kirillowna Naryshkina . When Peter's father died in 1676, Peter's half-brother Fyodor III ascended . the Tsar's throne.

The young tsar

After Fjodor's death in 1682, ten-year-old Peter found himself in the middle of a struggle for the throne of his country, which culminated in the First Strelizan Rebellion . Before his eyes, the Strelizi murdered his mother's two brothers and their foster father Matveev . This event is generally considered to be the key experience for Peter, as the hatred of the Strelizen was impressed on him.

In 1682 Peter and his older half-brother Ivan V were appointed tsar. However, due to the minority of the two brothers, Ivan's sister and Peter's half-sister Sophia , who based her power largely on the Strelizen, became regent . Formally, Ivan remained tsar alongside Peter until his death in 1696. But since Ivan was epileptic, eye-afflicted and mentally weak, he was not to have any influence on the affairs of government until his death.

From 1682 Peter stayed with his mother Natalja in the village of Preobrazhenskoye not far from Moscow. Natalja preferred to keep her son away from the Russian court, thus excluding him from the educational opportunities there. So Peter enjoyed a traditional old Muscovite upbringing. Since the 1680s, Peter had been involved in military and naval engineering exercises and maneuvers on the parade ground of Preobrazhenskoye not far from the Moscow suburbs and on the lake of Perejaslavl in a rather playful manner. In Preobrazhenskoye he was mainly concerned with the war game. With his peers he formed a warband of 50 men with whom he simulated wars. From this toy army with Fyodor Jurjewitsch Romodanowski as generalissimo , the Preobrazhensk bodyguard regiment developed , which in 1698 put down the Second Strelizan Uprising in the absence of Peter I and thus saved Peter's rule.

Taking office

Sophia's overthrow in 1689 by the court party of Peter and his mother meant Peter took office in Russian tsarism . This was preceded by a murder plot on Peter by around 600 involved Strelitzen, instigated by Peter's half-sister Sophia. But the plot was betrayed. The guilty were punished, his half-sister Sofia was sent to the New Maiden Convent and her advisor and lover, Prince Golitsyn , was disempowered and exiled to Siberia.

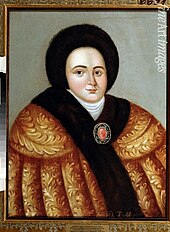

At this point, Peter had to bow to the conservative mother's claim to power. In January 1689, at the insistence of his mother, the seventeen-year-old Peter married Evdokija Lopuchina (1669–1731), three years his senior . She gave birth to the ruler in February 1690 a son named Aleksei. A second son, who was born in October 1691, died after only six months. The marriage with Evdokija lasted formally for ten years, but was completely shattered after a few years.

In the early 1690s, Peter showed little interest in government affairs. Inspired by technical innovations and the arts of foreign craftsmen in the Moscow suburb of Nemezkaja sloboda , Peter tried to get to know the local life and goings-on through visits. Tsar Peter, for example, often invited himself to Patrick Gordon , a noble landowner from Scotland who became the chief military advisor of the new Tsar. There he met the Swiss François Le Fort , who later became admiral of the navy. Through his connections to the foreign suburbs, he received the first, if only rudimentary, impressions of the Western European way of life at the time. Le Fort, who talked about foreign countries, their peculiarities and the high level of development of their culture, aroused in the young tsar a great curiosity, which was combined with the desire to bring Russia to a similar level. Peter learned the German and Dutch languages from the young man. The fact that a Russian tsar was going in and out of the foreign settlement meant, under the circumstances at the time, a blatant break with tradition.

In the first years as a Russian monarch, the young tsar was primarily concerned with building a powerful army. Numerous war games determined his everyday life. By chance, Tsar Peter's urge to go to the sea was also awakened. In June 1688 he and his teacher Franz Timmerman discovered an old English boat on the estate of his great-uncle Nikita Ivanovich Romanov . In 1691 shipbuilder Karsten Brant repaired the "grandfather of the Russian fleet ". It was with this botik that Peter I undertook the first sea voyage to Kolomenskoje . This aroused Peter’s interest in boats and ships, who was now dreaming of a port for Russia. Through that Karsten Brant he had two frigates and three yachts built, which formed the basis and the beginning of the future Russian naval power.

In order to improve Russia's maritime position, Peter sought to win new coastal places for his country. The only maritime access at that time was the White Sea near Arkhangelsk . The Baltic Sea was controlled by Sweden during this period, while the Black Sea was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Two years later, just before his mother's death, he sailed from Vologda to Arkhangelsk. When the ice was broken, a fleet from all over Europe met there. English, Dutch and Danes came here to trade in fur, hides, hemp, tallow, grain and potash. Here the monarch made himself acquainted with deep-sea fishing, the Murmansk overseas port and the commercial life there in the company of Gordon and Le Fort during stays of several months on the White Sea. The trips into the open sea there corresponded to the land maneuvers that Peter had carried out in the Moscow area in the autumn of 1694 as a preliminary exercise for the coming emergency. He moved the shipyard to the island of Solombala and founded an admiralty there as the basis for a Russian navy and merchant fleet. The first ship, the merchant ship "Sankt Paul", was launched in June 1694. After returning to Moscow, the tsar devoted himself to state affairs.

Sole rule

With the early death of his mother, who died in February 1694 at the age of only forty-one, the reason for the consideration for her that the young ruler had previously exercised also disappeared. However, he was also given the burden and responsibility of government affairs. In the following year Peter undertook a trip to several parts of his empire in order to convince himself of everything and to get to know the country with its inhabitants, the shortcomings and ailments of all kinds. After the death of his half-brother Ivan V, Tsar Peter I exercised sole rule in Russia.

Peter tried to get access to the Black Sea. But for this he had to defeat the Crimean Tatars in the area. In an agreement with Poland-Lithuania he started a war against the khanate of Crimea and against the overlord of the Crimean Tatars, the Ottoman sultan. Tsar Peter's main goal was to capture the Ottoman fortress of Azov , near the Don . In April 1695 the Russian army moved under him against Azov, but attempts at conquest failed. Peter returned to Moscow in November of that year. He immediately began building a large navy. In 1696 he launched over thirty ships against the Ottomans. In July 1696, Azov was captured in a second campaign. On September 12, 1698, Tsar Peter officially established the first Russian naval base in Taganrog .

The Great Embassy

From 1697 to 1698 Peter I was partly incognito as part of the Great Legation in Europe. The way led him via Livonia, Courland, Prussia to Holland and on to England. Alexander Menshikov was a companion on this trip . His friend François Le Fort acted as the nominal first envoy of the Grand Embassy in the Netherlands.

In August 1697 Peter wanted to gain experience in shipbuilding in Zaanstad, the Netherlands . Here he studied the construction of seaworthy sailors, which he copied as model ships and later built in Russia. After it was discovered who was really in Zaandam, Peter was forced to continue working in a shipyard in Amsterdam that was shielded from the public. There he began an apprenticeship as a carpenter in the shipyard of the East India Company in Krummendijk with shipyard master Gerrit Claesz Pool on August 20, 1697 . Here Peter worked on the construction of the frigate Peter and Paul and received a brilliant certificate from Pool.

Peter was received at all the major courts, but no one wanted to fulfill his political concern, the support of Russia in the fight with the Ottoman Empire. This also shattered hope of gaining a Black Sea port, whereupon Peter's efforts from now on shifted to the Baltic Sea.

Suppression of the Strelizos

While he was still in Vienna during the Great Embassy, in the summer of 1698, Peter received the news of a renewed uprising by the Strelitzen in Moscow and hurriedly returned to the Russian capital. The Strelitzen were seen as the greatest power risk for Peter's reform course. Peter I started an extermination campaign that lasted several months. Many thousands lost their lives in this way, others were banished to Siberia, Astrakhan , Azov and other places, the Strelitzen corps was abolished forever, the name abolished and declared dishonorable. During the suppression of the Strelitzen uprising, Peter I also suspected his wife Evdokija Fyodorovna Lopuchina of participating in the conspiracy and banished her to the Suzdal Monastery in 1698 .

After the destruction of the Strelitzen, nothing stood in the way of Peter I's reform plans. The aim was to modernize Russia according to Western European standards. These very erratic reforms were only stopped by the death of Peter I. His remodeling and modernization measures included promoting the economy by building large-scale businesses and supporting the establishment of private companies, reforms in the school system, the ban on wearing beards and Old Russian clothing, greater centralization and bureaucratization of administration and the creation of a table of nobility rankings . These reforms went down in history as the Petrinian reforms and contributed a large part to the rise of Russia as one of the leading powers in Europe (see section Reforms ).

Time of the Great Northern War

Bogged down in Turkey's policy, Tsar Peter I recognized that the lack of access to the Baltic Sea was affecting Russian trade. His efforts were therefore directed primarily against Sweden, with the aim of breaking Swedish supremacy in the Baltic Sea.

In the Second Northern War (1700–1721), Peter was able to turn the war around despite numerous defeats and considerable losses with the victory in the Battle of Poltava (1709). Tsar Peters great victory at Poltava and his subsequent conquests in the Baltic States were especially at the court of the Sultan at the urging of the Crimean Khan, Charles XII. and Mazepas followed with suspicion. Peter sent his ambassador to Istanbul and demanded the extradition of Charles. Ahmed III. had the ambassador thrown in jail. On November 10, 1710, the Russian monarch declared war. This resulted in a dangerous situation for Tsar Peter, which could jeopardize the success of Poltava, since no assistance was to be expected from the allies. So, reluctantly and weakened by illness, Peter invaded the Ottoman Empire with his army. The Ottoman troops surrounded him near Huși , a small town on the Prut . However, they did not take advantage of their superior position and honorably let him withdraw. In the Peace of the Prut , Peter undertook to cede the previously conquered Azov fortress and to withdraw from the territories of the Cossacks. In addition, the Russian Black Sea fleet there had to be abandoned.

In 1703 Peter founded the city of Saint Petersburg , which he called the new capital of the Russian Empire from 1710 without a corresponding decree.

Since 1712, Peter was married to a simple Lithuanian woman who had taken the name Katharina Alexejewna at his court in his second marriage . She bore him twelve children and after his death took over the rule as Catherine I.

On his second big trip to Western Europe in 1716/1717, this time not incognito, Peter I tried to complete his military success over Sweden by integrating Russia into the European state system. After a cure in Pyrmont , he visited his Danish ally, Frederick IV , in Copenhagen , met Prussia's King Frederick William I in Havelberg and traveled on to the Netherlands, where he spent the winter. Due to fever attacks, the tsar had to take it easy, but traveled on to Paris, where he was kindly welcomed by the seven-year-old King Louis XV. was received. On December 22, 1717 he became a member ( associé étranger ) of the Académie royale des sciences . After a six-week stay in Paris, Peter went back to Spa for a cure to travel back to St. Petersburg via the Netherlands and Berlin.

The conflict with his son Alexei came to a head in 1718. After his escape via Austria to Italy, he had Alexei brought back to Russia in 1717, disinherited him and tried him for high treason. Alexei was forced to abdicate and sentenced to death, but died of torture before execution on June 26th.

Peter as emperor

The Great Northern War ended in 1721 with the Peace of Nystad . Russia was able to establish itself as a leading power in Northeastern Europe.

Immediately after the peace agreement with Sweden, Peter changed his official title from Tsar to Kaiser (Russian Император Imperator ) in accordance with the increased importance of Russia's foreign policy . The Russian rulers wore this title until 1917. In 1722, Peter changed the traditionally practiced succession to the throne, which was dependent on the order of birth. Now the ruling regent was free to choose his successor, also from outside the family, and to depose an unworthy successor.

Already ailing, Peter, in his efforts to modernize Russia, ordered the establishment of a Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg on February 8, 1724 . His summer residence was the Peterhof (see also Neptune Fountain ).

death

Immediately after recovering from a serious illness (he suffered from urinary retention ), Peter set out on a long sea voyage in autumn 1724. Among other things, it led him to Schluesselburg , where he wanted to check the work on the new Ladoga Canal . On November 5th he returned to Saint Petersburg, but did not go ashore, but instead sailed on along the Gulf of Finland. His destination was the rifle factory near Lachta. When it was dark, a storm was coming. Not far from the shores of Lake Lachta, Peter the Great discovered a capsized boat, and the crew threatened to drown. To help the sailors and soldiers from Kronstadt, he waded into the ice-cold water of the lake up to his waist. Here his personal commitment and his ruthlessness towards himself became evident. On February 8, 1725, the fifty-two-year-old tsar died in Saint Petersburg as a result of his rescue act (bladder disease in connection with liver atrophy).

Peter left no will. The assertion that has arisen since the time of Napoleon that Peter had committed all future successors in a will to strive for Russian rule over Europe is a propaganda falsification. It was exposed as such as early as 1828, but this notorious forgery has repeatedly given rise to misinterpretations and allegations.

Reforms

Peter the Great initiated numerous reforms in Russia aimed at transforming Russia into a modern state. Linked to this was the founding and promotion of the new capital Saint Petersburg .

Culture and sciences

The introduction of West Central European clothing was part of the cultural modernization . The traditionally long beards were subject to a beard tax . The Julian calendar was introduced in Russia, although the rest of Europe was slowly adopting the Gregorian calendar during this period .

In terms of technology and science, too, Peter I oriented himself on the then modern models. He initiated the Academy of Sciences and carried out a script reform .

administration

The Russian monarch made extensive changes in the administration of his empire. The basis of this reform work was the Swedish regulations, which were tailored to the specific conditions in Russia. So Peter I created the mayor's office, set up a senate, which prepared new laws and directed the local and central organs, as the highest administrative authority. In addition, the colleges were created in his government, comparable to the specialist ministries in Western Europe. The introduction of the rank table in 1722, which divided the administrative and military careers into 14 rank classes, was groundbreaking.

The Russian Empire was administratively divided into eight governorates and about 50 provinces.

military

By redesigning the army and establishing the Russian fleet , Peter the Great was able to push back the Swedes in the Great Northern War after initial failures .

economy

Peter built a mercantilist economy. This particularly includes his strong promotion of the manufactories . When Peter took office, there were only ten factories in Russia. The promotion of industry was closely related to the needs of the army during the long war years. But there were also many manufactories and factories that produced consumer goods. Some factories, among them the Menshikov mirror factory, were already working for export. In 1716 the spinning wheel was introduced in Russia. A year before his death, Peter I ordered that all foundlings should be educated to be craftsmen and manufacturers. In the last year of his reign there were around 100 factories, including some with more than 3,000 employees - the Tula arms factory being outstanding . The German mining specialist Baron von Hennin, who was chairman of the mining college, played a major role in the development of the iron and steel industry. At the end of the reign, statistics register a balanced state budget of about 10 million rubles.

church

Tsar Peter I had always viewed the Russian Church as an oppositional (strong) opponent of his reforms. Therefore, after the death of Patriarch Adrian (1700), he left the post of highest clergyman vacant. He particularly hated the Old Believers (Raskolniki) , whom he fought against through numerous laws. In 1719 the Jesuits were expelled from Russia. From January 25, 1721, the Tsar finally placed the Russian Orthodox Church under state administration. The Spiritual College, later the " Holy Ruling Synod ", replaced the Moscow Patriarchate, which had existed since 1593. In the penultimate year of his reign, Tsar Peter I struck a decisive blow against idleness in the monasteries.

progeny

From his marriage to Evdokija Lopuchina , Peter the Great had three sons:

- Alexei (1690–1718), Tsarevich of Russia and father of Peter II ,

- Alexander (1691–1692),

- Paul (1693).

The marriage to Martha Skawronskaja (later Catherine I ) had twelve children (eleven according to other counts), of which only two daughters reached adulthood:

- Anna (1708–1728), ancestor of the Romanow-Holstein-Gottorp line ,

- Elisabeth (1709–1762), Tsarina of Russia 1741–1762.

Honors

In his honor monuments were built, see monuments to Peter I. The Peter the Great Gulf was named after him; also several Russian ships, see Pyotr Veliki . The main inner belt asteroid (2720) Pyotr Pervyj is named after Peter the Great.

literature

- Hartwig Ludwig Christian Bacmeister : Contributions to the history of Peter the great. 3 volumes. Hartkoch, Riga 1774–1784.

- Olaf Brockmann: Peter the Great's break with old Moscow. Korb's diary and diplomatic reports from Moscow on the events of 1698 and 1699 . In: Yearbooks for the History of Eastern Europe. Volume 38, 1990, pp. 481-503.

- Erich Donnert : Peter the Great. Koehler and Amelang, Leipzig 1988, ISBN 3-7338-0031-1 .

- Jörg-Peter Findeisen : The struggle for control of the Baltic Sea. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-428-07495-5 .

- Daniil Granin : Peter the Great. Volk und Welt, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-353-01190-0 .

- Gerhard Anton von Halem : Life of Peter the Great . 3 volumes, Münster 1803–1804

- Robert K. Massie : Peter the Great. His life and his time . Fischer, Frankfurt 1992, ISBN 3-596-25632-1

- Alexander Moutchnik : The "Strelitzen Uprising" of 1698 . In: Popular uprisings in Russia. From the time of turmoil to the “Green Revolution” against Soviet rule , research on Eastern European history, Volume 65, Ed. Heinz-Dietrich Löwe. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-447-05292-9 .

- Reinhold Neumann-Hoditz: Peter the Great. In self-testimonials and picture documents . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2000, ISBN 3-499-50314-X

- Hans-Heinrich Nolte : Small history of Russia . Reclam, Ditzingen 2003, ISBN 3-15-010541-2 (also at bpb ).

- Viktor Ozerski: Ruler of Russia from Rurik to Putin . Phoenix, Rostov-on-Don 2004, ISBN 5-222-05545-0

- Sergej F. Platonov: Russkaja istorija. Moskva 1995, ISBN 5-7233-0128-4

- Benjamin Richter: Scorched Earth. Peter the Great and Charles XII. The tragedy of the first Russian campaign . MatrixMedia Verlag, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-932313-37-0

- Martha Schad (Ed.): Power and Myth. The great dynasties. The Romanovs . Weltbild, Augsburg 2000, collector's editions

- Jacob von Staehlin : Original anecdotes from Peter the Great. Winkler, Munich 1968

- Voltaire : Histoire de l'Empire de Russie sous Pierre le Grand, par l'auteur de l'histoire de Charles XII . Geneva 1761 and 1763. German: History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great . Frankfurt and Leipzig 1761 and 1764.

- Reinhard Wittram : Peter I., Czar and Kaiser. On the story of Peter the Great in his time . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1954, ISBN 3-525-36140-8

- Fiction

- August Strindberg : The great one. Novella. In: The most beautiful stories in the world. House book of immortal prose. Preface by Thomas Mann . Übers. Willi Reich . Kurt Desch, Munich 1956, Part 2, pp. 488-499

Film adaptations

- Peter's youth . 2 pieces, GDR / USSR 1981.

- Peter the Great . TV miniseries, 4 parts, USA 1986.

Web links

- Literature by and about Peter I in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ In contemporary parlance, it was customary to continue speaking of the tsar even abroad until 1917 . This did not correspond to the current dignity of the empire, but the continued existence of a specifically Russian reality and the fact that the Moscow tsarist empire served as the basis of the new empire. In the 19th century, this led to a conceptual language in literature that was not appropriate to the source and to an outmoded conceptual apparatus in German literature. - Cf. Hans-Joachim Torke: The Russian Tsars, 1547–1917 , p. 8; Hans-Joachim Torke: The state-related society in the Moscow Empire . Leiden 1974, p. 2; Reinhard Wittram: The Russian Empire and its shape change . In: Historische Zeitschrift , Vol. 187, H. 3 (June 1959), pp. 568–593, p. 569.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Torke: The Russian Tsars, 1547-1917 , p. 156.

- ↑ a b Erich Donnert: The Russian Tsar Empire. Munich 1992, ISBN 3-471-77341-X , p. 127 ff.

- ^ A b Hans-Heinrich Nolte: Small history of Russia. Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-89331-651-5 , p. 89 ff.

- ↑ Wolf Schneider: Imperator without mercy. In: Geo epoch: In the empire of the tsars. Hamburg 2001, ISBN 3-570-19322-5 .

- ↑ Andrea Schröder: Havelberg: The Amber Room on the Elbe | svz.de . In: svz . ( svz.de [accessed June 2, 2018]).

- ^ List of members since 1666: Letter P. Pierre I, dit le Grand. Académie des sciences, accessed on February 3, 2020 (French).

- ^ Sergei Fjodorowitsch Platonow: Russkaja istorija. Russkoje Slovo, Moscow 1995, ISBN 5-7233-0128-4 , p. 294.

- ↑ https://archivalia.hypotheses.org/68962 .

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel : Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. Ed .: Lutz D. Schmadel. 5th edition. Springer Verlag , Berlin , Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7 , pp. 186 (English, 992 pp., Link.springer.com [ONLINE; accessed on September 9, 2019] Original title: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . First edition: Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg 1992): “1972 RV 3 . Discovered 1972 Sept. 6 by LV Zhuravleva at Nauchnyj. "

- ↑ Peter the Great Fernsehserien.de . Retrieved October 27, 2017.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Fyodor III |

Tsar and Emperor of Russia 1682–1725 |

Catherine I. |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Peter the Great |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Peter I .; Пётр I (Russian); Пётр Великий (Russian); Пётр I Великий (Russian); Pyotr I Velikiy; Romanov, Pyotr Alexejewitsch; Романов, Пётр Алексеевич (Russian) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian tsar |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 9, 1672 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Moscow , Tsarist Russia |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 8, 1725 |

| Place of death | Saint Petersburg , Tsarism Russia |