Whiskers

Beard hair is part of the human body hair . The growth zone of the whiskers is usually distributed around the mouth, chin, cheeks and the front of the neck. The characteristic properties of the hairy areas are described in detail in the article Hair . Beard hair is usually thicker shaft, more rigid, and stays shorter than the hair on the head.

biology

Beard hair is usually widespread from puberty onwards and is therefore one of the secondary sexual characteristics . Beard growth is triggered by the androgen testosterone . Visible beard hair in women is referred to as a " lady's beard ". Women's beards may start growing after menopause (menopause).

Beard growth from puberty

By endocrine processes in the body of male puberty begins at the end (between the ages of about 14 and 18 years) of beard growth. As a rule, a delicate fluff appears first on the upper lip, which is initially soft, but then gradually becomes harder. Shortly afterwards, the first hair appears on the ears, as this is where the actual beard growth begins. A little later the first hairs also sprout on the chin, where they then spread towards the neck. Finally, the hair spreads over the cheeks.

Only now is it called a real beard, and a bare face requires regular shaving, but this takes some time, as this stage is only reached about 4–5 years after the pubic hair first appears . The thickness of the hair is partly controlled by the male hormone testosterone and genetically , regular shaving has no influence on this. Nevertheless, the speed of growth and the thickness of the beard increase with age due to the increasing hormone level and is then about 2.8 mm per week.

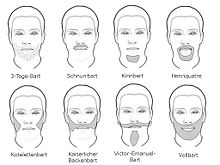

Beard shapes

There are different ways to wear beards, one speaks of beard shapes or beard costumes. The forms worn differ according to culture, fashions and epoch.

Common beard shapes are:

- Whiskers

- Three-day beard

- Goatee: chin beard, also called "goatee", whereby the beard is left below the mouth. Variation: "Petit Goatee", whereby only a widening strip is left from the lower lip to the chin. Variation: "chin stripe", whereby the stripe is very narrow.

- Henriquatre: round-the-mouth beard, "trade union beard", warrior beard, hunter's beard, named after Henry IV of France . Variation: "Van Dyck".

- Goatee

- Knebelbart : Also called Victor Emanuel beard (after Victor Emanuel II. ) Or musketeer beard, whereby the connection between the mustache and chin beard is shaved off. Full bearded variation: “Balbo”, with cheeks and sideburns shaved. Famous Bearer: Buffalo Bill

- sideburns

- Mongolian mustache: Full mustache, which is laterally extended down to the edge of the lower jaw, similar to Henriquatre, but with a shaved chin; popularly called "pimp beard" or "horseshoe",

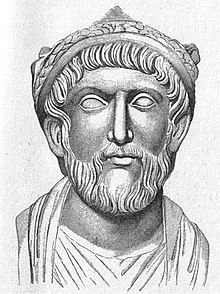

- Schiffer, Frisian, beard milling machine, Schiffer's curl, also teacher's beard: full beard, but without growth on the upper lip and higher cheeks. This beard shape is already cited in ancient Greek busts.

- Mustache (mustache, mustache, mustache): Beard exclusively on the upper lip. Variation: pencil beard, whereby only the beard hairs near the upper lip are left in a thin strip.

- Soul Patch : Under the lower lip in different lengths and densities

- Beard

- Kaiser Wilhelm Beard

Longer beards are sometimes braided on the chin.

The milk beard , on the other hand, is just a metaphor for a very young man with the first downy beard and alludes mockingly to the clearly visible edges of milk that remain on the upper lip or the skin around the mouth when children drink.

Shave and cut

The hairs are usually shortened by shaving ; The period in which you have to shave in order to suppress visible hair depends on the growth of your beard and can range between several times a day and weekly. Used razor , razor , razor , system razors or Shavette . A common misconception is that more frequent shaves will stimulate beard growth. This mistaken belief is due to the subjective feeling that arises when driving out the very hard stubble.

The length of the whiskers can be considerable. The longest beard was worn by Hans Langseth , a Norwegian who died in the USA in 1927 with a hair length of 5.33 m. Louis Coulon's (* 1828) beard was similarly long.

The shave can either be done completely, with all beard hair removed, or selected parts of the facial hair are left standing or only trimmed (cut). This form of Bartbehaarung needed, to obtain, a regular beard trimming , it also is often Mustache Wax used.

Cultural history

In earlier times the beard was seen as a symbol of strength and as an ornament of masculinity, which is why careful care developed. Views of what to do with the beard differ considerably from culture to culture; A beard that deviates from the norm is often a sign of neglect or strangeness. Had the beard had in the early history of mankind, above all, a cultic character, which many religious components, he is in the presence beside especially in the secularized Western world both an expression of individuality as well as in certain forms mode .

antiquity

The pharaohs of ancient Egypt (even if they were women) wore ceremonial beards as a sign of their virile omnipotence. This ceremonial beard was, however, an artificial, stylized dummy ; the natural growth of the beard was shaved. The beard was a sign of social distinction and was intended to illustrate differences in class in the old high cultures.

Until the submission to Alexander the Great, the Greeks were mostly proud of their beards, which were only shaved on occasions of mourning or as punishment. However, in the classical period the so-called "strategist's beards" appeared, short beards that did not interfere with combat. When the Macedonians came to power, it became a custom for the upper classes to shave. The saying goes from this time: A beard does not make the wise man . Because even in the times of Alexander, philosophers wore long hair and long beards.

Until the 3rd century BC The Romans apparently did not know about shaving. With the contact with the Greek culture of Hellenism , it also became common here to shave. Scipio Africanus the Younger is said to have been the first Roman to have a clean shave. This custom soon became generally accepted in Rome, at least among the upper class; this only changed in the century and a half between Hadrian and Diocletian : Hadrian wore a full beard as a sign of his connection with the classical, pre-Macedonian Greek culture. Between Hadrian and Caracalla almost all emperors had full beards, the soldier emperors preferred a three-day beard . Between Constantine the Great and Phocas , almost all rulers (with a few exceptions such as Julian the Apostate ) were clean-shaven for centuries , as this was considered typically Roman in late antiquity .

The beard fashions among the peoples outside the Roman Empire are only partially passed on. From the Roman point of view, a full beard next to trousers was a typical sign of a barbarian . Some Persian rulers worked their beards with gold thread. Tacitus reports in his Germania (98 AD):

- “This, which is also rarely practiced by other peoples of Germania and with the personal daring of the individual, has become a general custom in the chats : as soon as they have grown up, to let their hair and beard grow, and only after killing an enemy the sworn costume pledged to bravery to lay off their face. ”(Tac. Germ. 31,1).

It is true that the assertion of Roman authors that Teutons always had long beards cannot be confirmed, but as a visible sign of initiations , the hairstyle was given particular importance. The tribal name Langobard , which is usually derived from "long beards", could go back to the external distinction from the Germanic peoples.

Judaism, Christianity, Islam

Judaism

The Old Testament knows two commandments about wearing a beard. In Leviticus 19:27 it says (in the translation according to Luther, Bible text in the revised version of 1984 (German Bible Society)): You should not cut your hair all around on your head nor trim your beard . This is aimed at all Israelites, and is above all a rejection of pagan hair and beard costumes that had religious meanings. Leviticus 21: 5 is addressed to the priests: They should not shave a bald head, trim their beard or cut into their bodies . Here, too, the background is the modification of the body in the cult of the pagans of that time, who u. a. also included tattoos and targeted scarring. Based on these verses, various interpretations have emerged in Judaism as to the extent to which a devout Jew is allowed to shave and trim himself. Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews therefore often wear long beards and sometimes sidelocks .

Christianity

Christianity does not have a clear beard, rather different traditions and interpretations alternate in time and in the denominations as to whether a man has to wear a beard or not. While the Catholic clergy are mostly clean-shaven, the Amish , for example, as married men , wear boat ruff . Monastic orders sometimes have fixed shaving times.

Islam

In Islam it is said that Muhammad's beard , like his head hair, was hardly gray until his death. Devout Muslims follow some hadiths , i.e. traditions of the prophets and the Sahaba , in which it is prescribed that the beard must be worn and the mustache trimmed, and that the length of a fist is required below the chin.

19th and 20th centuries

The beard had become a completely secularized aesthetic quantity in Europe. The beard costume was subject to the fashion that emanated from the ruler's court. So Louis XIV set the clean shave as the standard, while Henry IV popularized the beard named after him (see above).

Intellectuals wore it as a sign of criticism and revolutionary sentiments (see e.g. Karl Marx , Pjotr Kropotkin or Friedrich Nietzsche ), while rulers rediscovered the beard, which was frowned upon until the 18th century ( Friedrich the Great was shaved), to make it look more common to ordinary people adapt. This in turn made them role models for loyal citizens to imitate the beard costume again (see Kaiser Wilhelm I and Kaiser Wilhelm II ).

Early 19th century: the bourgeois revolutionary wears a beard

The beard reached its peak in the 19th century. During the revolutions from 1789 to 1848, the beard had become a symbol of closeness to the people, but also of radicalism. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn , who initiated the German gymnastics movement in 1811 with the aim of preparing young people for the fight against the Napoleonic occupation and for the rescue of Prussia and Germany , propagated the beard, which had gone out of fashion in Napoleonic France, as a deliberate demarcation from the French occupiers. For Jahn, the return to the beard was also a return to glorified medieval ideals. A few years later, French bourgeoisie who stood in opposition to the backward-looking Charles X regime often wore beards.

Eugène Delacroix showed this change in his iconographic painting Freedom Leads the People , which immortalized the barricade battles of the July Revolution of 1830 . The worker on the left edge of the picture is still beardless, the citizen fighting with him is dressed in sober black, has a top hat and a beard. The shape of the beard in France increasingly signaled the political views of its wearer: while conservative royalists were clean-shaven, Republicans wore sideburns and a small goatee. Moderate Republicans, on the other hand, did without the goatee. Anyone who wore a goatee signaled that they were still a supporter of Napoleon . Liberals, politically between moderate Republicans and conservatives, preferred the mustache. The full beard, on the other hand, was limited to artists and political outsiders.

The mustache becomes the officer's mark

So-called hussar regiments , a branch of light cavalry troops , gradually became a regular part of the army in large parts of continental Europe, following the Hungarian model from the late 17th century. Her uniform picked up elements of the Hungarian national costume all over Europe: wing or fur hat ( Kolpak ) or later also shako , tight-fitting trousers and laced jackets (initially the short dolman , from the middle of the 19th century the tabard-like Attila ) and fur-trimmed jackets (mente ), which were carried over the shoulder in summer. Most of the members of such hussar regiments, which had been known throughout Europe since the Napoleonic Wars at the latest, wore a full mustache, the so-called Mongolian beard, which extended to the edge of the lower jaw. A mustache, however, became the usual beard for members of the regiment.

In Great Britain in 1830 an attempt was made to limit the wearing of mustaches to members of elite cavalry regiments such as the Life Guards , the Horse Guards and the Hussar regiments, but eventually had to give in and allow all military personnel to wear a mustache. There was a similar development in France, where from 1833 all military personnel were allowed to adorn themselves with a mustache. In Spain, however, the wearing of a mustache was limited to officers until 1845. By the middle of the 19th century, almost all of the European cavalry and most of the regular officers wore a mustache. The beard became so common that cavalry members who were too young to have an impressive mustache painted it on themselves. In parts of Europe, however, his hairstyle was limited to the military. In Bavaria in 1838 an ordinance was issued that prohibited civilians from having mustaches under threat of arrest and a forced shave.

Via the British royal family, the fashion became popular in aristocratic circles outside of the military. The British Prince Consort Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha , the second-born son of an insignificant continental European duchy, whom Queen Victoria married in 1840, wore a mustache and sideburns and his hairstyle influenced the British upper class.

1830 to 1850: The revolutionary wears a full beard

In large parts of Europe, a civilian who refrained from having a clean shave underlined his political stance, which differed from the majority, until about the first half of the 19th century. A Paris police report from 1840 laments

“... we painfully see many members of the working class in blouses, with beards and mustaches, who obviously spend more time on politics than on work, reading Republican newspapers and disgusting pamphlets that are published with the sole aim of getting them all at once To lead astray ... "

In Great Britain there were even two groups who, with their beards, signaled their revolt against the existing order. In addition to members of the working class, Irish freedom fighters also wore beards. In Russia, Slavophile nobles, including Alexei Stepanowitsch Chomjakow , Ivan and Konstantin Aksakow , who appeared in traditional Russian clothing and beards in 1849 in front of Tsar Nicholas , who was only adorned with the military mustache, wanted their criticism of increasing Western influence on Russia and a return to it claim traditional Russian values. With their full beards, they wanted to remember the Russian rural population and the Russian past and pick up on the beard of the Russian Orthodox clergy. Tsar Nikolaus, descendant of Tsar Peter the Great , who imposed a beard tax on wearers of traditional Russian beards, saw all Russian nobles with full beards as critics of his rule. Not only did he officially show his displeasure with such beards, he also made it clear that Russian nobles with full beards could not expect an appointment to an official Russian office.

Second half of the 19th century: the full beard is also becoming socially acceptable

By 1850 all movements that were supposed to give the bourgeoisie a greater say had largely failed in Europe. The beard costume lost its political importance and in the second half of the 19th century beard was picked up in various forms in all social circles without this being linked to a political message or membership in the military.

The social historian Oldstone-Moore is of the opinion that the decisive part in this change was played by Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte , who after years of exile during the Second Republic was French President from 1848 to 1852 and from 1852 to 1870 as Napoleon III. Was Emperor of the French . With the coup d'état of December 2, 1851 , the president, who had emerged from a popular election, established a dictatorship that resulted in the Second Empire a year later . Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte was not only the first bearded French head of state since the 17th century. His style was also copied in large parts of France.

In Great Britain it was the popular entertainer Albert Richard Smith who gave the beard a coat of respectability. The bearded Smith performed more than two thousand times between 1852 and 1858 with a staging of his ascent of Mont Blanc in front of a British audience. More than half a million British people saw his show, including the British Prince Consort who saw it in 1853 and Queen Victoria who saw it a total of three times and invited Smith to private screenings at Osbourne and Windsor Castle . Oldstone-Moore calls Smith a prototype of a new masculinity: independent, efficient, courageous and with a beard ornament. Its success was based not on inherited wealth or other privileges, but solely on willpower. In British society, which valued such qualities in a man, the beard became a symbol of these qualities.

A similar change took place in the United States of America: Abraham Lincoln was the first American president to wear more than just sideburns. Oldstone-Moore believes that Lincoln chose his beard dress very carefully. He renounced the full beard or the large mustache, as it was characteristic of American generals, and chose the whiskers as it was worn by pastors in particular. Even more than Lincoln, however, it was the influential American poet Walter Whitman who introduced the link between beard and masculinity into American imaginations. For Whitman, the shave represented fear and escape from the hardships of life. The beard, on the other hand, stood for a man who faced the challenges and joys of life. Each edition of his main work Leaves of Grass was also adorned with a photograph of a bearded, simply dressed and sun-scorched Whitman. The poet, widely read in both the USA and Great Britain, became a symbol of modern masculinity based on physical vitality and resilience as well as fearless behavior.

First half of the 20th century: the modern man is clean-shaven again

Shaving became cheaper and easier in 1901 with the invention of the safety razor by King Camp Gillette . With this disposable item, every man could easily afford the daily shave. Gilette's invention is only seen as benefiting from a development towards beardlessness, not as the cause of this trend. In the 19th century, doctors had regularly argued that a beard protected the skin from sun and weather and filtered dust from the air we breathe. Since Louis Pasteur's development of the germ theory, this argument became increasingly untenable and at the beginning of the 20th century there were more articles in newspapers, magazines and medical journals that associated the beard with the transmission of diseases: for example, in 1907 a French scientist reported that a beard wearer Kissing can transmit tuberculosis and diphtheria pathogens. In 1909 the medical journal Lancet published a study by British doctors who had come to the conclusion that clean-shaven men were less likely to suffer from colds. The clean shave of the face developed accordingly to the new standard, which was associated with youth, energy, purity and reliability. Beards gradually reverted to being outside of any social norm. This development could be observed more quickly in North America than in Europe: as early as 1907, the Burlington Northern Railroad in the United States made its conductors beardless, and in 1915 the Los Angeles Police Department prohibited the transportation of police officers who still wore mustaches. After the First World War , the overflowing full and highly stylized whiskers popular in the previous century had largely disappeared in the western world.

It is often argued that the requirement for soldiers to easily and quickly put on gas masks during gas attacks put an abrupt end to the beard costumes that had been popular until then. The social historian Oldstone-Moore thinks this is not true. In his opinion, a trend towards close shaving began even before the First World War, and he points out that in Great Britain, even before the outbreak of the First World War, members of the military repeatedly asked to no longer have to wear the mandatory mustache. In 1915, in the second year of the First World War, the British King George was forced to issue an admonition to the troops to adhere to the shaving regulations that provided for the mustache. It was not until 1916 that the British General Staff gave in and renounced this rule, which had led to conflicts within its own troops.

Oldstone-Moore cites two examples of this change of standards: 1912 appeared in the October issue of the pulp magazine All-Story Magazine for the first time a history with the fictional character of Tarzan as protagonists. The British nobleman, who grew up among monkeys, shaves to underline his belonging to humans:

“Although he had seen men in his books with a large amount of hair above the lip, on the cheeks and on the chin, Tarzan was still concerned. Almost every day he wet his sharp knife and scratched and scraped away his young beard to get rid of this degrading symbol of the monkey. And so he learned to shave - coarse and painful, that's true - but effective. "

Oldstone-Moore's second example is the British officer Thomas Edward Lawrence , better known by his nickname Lawrence of Arabia, who also used the clean shave to set himself apart from his Arab allies or to shave daily even under the most difficult circumstances.

present

With the advent of the counterculture of beatniks and hippies , the beard became fashionable again in the 1960s, as a symbol of individuality and lateral thinking. The mustache was very popular in the 1980s. The three-day beard became popular in the 1990s and 2000s. In the wake of the hipster movement , the beard, especially as a longer full beard, became more and more of a fashion accessory in Western-Occidental culture from around 2010.

Other cultures

In Sikhism and the Rastafari movement beards are worn for religious reasons. Sadhus , Hindu wandering monks, have their heads and whiskers stand up as a sign of their ascetic lifestyle.

Ice hockey players have been wearing so-called playoff beards during the playoffs since 1980 .

Beards in Literature and Science

The Roman Emperor Julian (331–363) already wrote an ironic sketch Misopogon (Eng. "The Barthasser"). A detailed treatise on beards comes from the second half of the 12th century, written by Burchardus, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Bellevaux in Franche-Comté. It is addressed to the Cistercian lay brothers. In the author's view, beards were appropriate for the uneducated agricultural lay brothers, but not for the priest-monks.

Especially in times when even more uniform clothing, beard and hairstyle conventions prevailed than today, even a brief mention of the beard dress could help characterize a literary figure. One example is The Subject in Heinrich Mann 's novel of the same name , who demonstrates his loyalty to Wilhelm II with his “hangover-threatening” “It has been achieved” beard . Also in the story The railway accident of Thomas Mann are the beards of two protagonists in addition to quite a few other accessories to the attributes that the "Lord" who defies public regulations sovereign, the "man" who represents the state in this case, distinguish.

Idioms

- The saying that is (only) a quarrel about the emperor's beard dismisses a quarrel as irrelevant.

- To flatter someone's beard or to smear honey around their beard is to flatter them.

- Barba non facit philosophum, neque vile gerere pallium (“A beard doesn't make a philosopher by a long way, not even to wear a cheap coat” according to Aulus Gellius ).

See also

- Sheared (today a swear word)

- Hypertrichosis (disease)

literature

- Frank Gnegel: Beard off. On the history of self-shaving. DuMont Reiseverlag, Ostfildern 1998, ISBN 3-7701-3596-2 .

- Helmut Hundsbichler: Beard . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 1490 f.

- Barbara Martin: The bearded man. Guide to the history of the beard. Theater der Zeit, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-942449-10-6 .

- Christopher Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2015, ISBN 978-0-226-28414-9 .

- Allan Peterkin: One Thousand Beards: A Cultural History of Facial Hair. Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver 2002, ISBN 1-55152-107-5 .

- Jörg Scheller , Alexander Schwinghammer (Ed.): Anything Grows. 15 essays on the history, aesthetics and importance of the beard. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-515-09708-6 .

- Jörg Scheller: Avant beard. A souped-up history of the full beard in pop music and its niches. Online publication on pop-zeitschrift.de, 2015.

- Christina Wietig: The beard: On the cultural history of the beard from antiquity to the present. (PDF; 514 kB) Dissertation . University of Hamburg, 2005.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christina Wietig: The beard. On the cultural history of the beard from antiquity to the present. Hamburg 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ Christina Wietig: The beard. On the cultural history of the beard from antiquity to the present. Hamburg 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ a b beard. In: Brockhaus Bilder-Conversations-Lexikon. Volume 1, Leipzig 1837, pp. 186-187. (Zeno.org online library, accessed June 14, 2012)

- ↑ Jörg Fündling: Commentary on Hadriani's Vita from the Historia Augusta. (= Antiquitas / 4 / 3rd volume 4.2). Habelt, Bonn 2006, OCLC 315036746 , pp. 1128-1131

- ^ Paul Zanker: The mask of Socrates: The image of the intellectual in ancient art. Munich 1995, pp. 206-221.

- ^ Online edition of Germania von Tacitus with German translation .

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: The Germanic peoples. CH Beck, Munich 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ al-Buchari, 5892.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2464.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2515.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2556.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2686.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2715.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2689.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2718.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook heading 2706.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2731.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Beards of the Romantic Imagination . Ebook position 2768.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2869.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2931.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2939.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2947.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2830.

- ^ Walt Whitman's lost advise to America's men: meat, beards and not too much sex. The Observer. April 30, 2016 , accessed May 2, 2016.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 2955.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Patriarch of the Industrial Age . Ebook position 3449.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3471.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3485.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3449.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3501.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3436.

- ^ Edgar Rice Burroughs : Tarzan of the Apes , quoted from Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3456.

- ↑ Oldstone-Moore: Of Beards and Men: The Revealing History of Facial Hair . Chapter: Corporate Men of the Twentieth Century . Ebook position 3429.

- ↑ A beautiful beard knows no gender in Die Welt, May 22, 2014

- ↑ https://www.watson.ch/Unvergessen/Eishockey/527705057-Zwei-rasierfaule-und-aberglaeubische-NHL-Spieler---erhaben---den-Playoff-Bart

- ^ RBC Huygens (ed.): Apologiae duae: Gozechini epistola ad Walcherum; Burchardi, ut videtur, Abbatis Bellevallis Apologia de Barbis. (= Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis LXII). Brepols, Turnholti 1985. (with an introduction by Giles Constable on beards in the Middle Ages)