Great Northern War

| date | February 12, 1700 to September 10, 1721 |

|---|---|

| location | Central, Northern and Eastern Europe |

| exit | allied / Russian victory |

| Peace agreement | Preliminary Peace in Stockholm, Peace of Stockholm (1719) , Peace of Stockholm (1720) , Peace of Frederiksborg , Peace of Nystad |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

|

Charles XII. † |

Peter the Great |

| Troop strength | |

|

Initial strength : 76,000 Swedes (1707: 120,000) 5,000 Holstein support 1,700: 10,000 Lüneburgers 13 Dutch ships 12 English ships Later allies: 24,000 Poles & Lithuanians 4,000–9,000 Cossacks 130,000 Ottomans |

Initial strength: 110,000 Russians 40,000 Danes & Norwegians 30,000 Saxons 50,000 Poles & Lithuanians 30,000 soldiers of the Cossack army Later allies: 50,000 Prussians 20,000 Hanoverians |

1st phase: Swedish dominance (1700–1709)

Riga I • Jungfernhof • Varja • Pühhajoggi • Narva • Pechora • Düna • Rauge • Erastfer • Hummelshof • Embach • Tartu • Narva II • Wesenberg I • Wesenberg II

Arkhangelsk • Lake Ladoga • Nöteborg • Nyenschanz • Neva • Systerbäck • Petersburg • Vyborg I • Porvoo • Neva II • Koporje II • Kolkanpää

Vilnius • Salads • Jacobstadt • Walled Courtyard • Mitau • Grodno I • Olkieniki • Nyaswisch • Klezk • Ljachavichy

Klissow • Pułtusk • Thorn • Lemberg • Warsaw • Posen • Punitz • Tillendorf • Rakowitz • Praga • Fraustadt • Kalisch

Grodno II • Golovchin • Moljatichi • Rajowka • Lesnaja • Desna • Baturyn • Koniecpol • Weprik • Opischnja • Krasnokutsk • Sokolki • Poltava I • Poltava II

2nd phase: Sweden on the defensive (1710–1721)

Riga II • Vyborg II • Pernau • Kexholm • Reval • Hogland • Pälkäne • Storkyro • Nyslott • Hanko

Helsingborg • Køge Bay • Gulf of Bothnia • Frederikshald I • Dynekilen Fjord • Gothenburg I • Strömstad • Trondheim • Frederikshald II • Marstrand • Ösel • Gothenburg II • Södra Stäket • Grönham • Sundsvall

Elbing • Wismar I • Lübow • Stralsund I • Greifswalder Bodden I • Stade • Rügen • Gadebusch • Altona • Tönning II • Stettin • Fehmarn • Wismar II • Stralsund II • Jasmund • Peenemünde • Greifswalder Bodden II • Stresow

Alliance treaties

Preobrazhenskoe (1699) • Dresden (1699) • Narva (1704) • Dresden (1709) • Thorn (1709) • Copenhagen (1709) • Hanover (1710) • Lutsk (1711) • Adrianople (1713) • Schwedt (1713) • Stettin (1715) • Berlin (1715) • Greifswald (1715)

Peace treaties

Traventhal (1700) • Warsaw (1705) • Altranstädt (1706) • Pruth (1711) • Frederiksborg (1720) • Stockholm (1719) • Stockholm (1720) • Nystad (1721) • Stockholm (1729)

Surrenders

The Great Northern War was a war waged in Northern , Central and Eastern Europe from 1700 to 1721 for supremacy in the Baltic Sea region .

An alliance of three, consisting of the Russian Empire and the two personal unions Saxony-Poland and Denmark-Norway , attacked the Swedish Empire in March 1700 , which was founded by the eighteen-year-old King Charles XII. was ruled. Despite the unfavorable starting position, the Swedish king initially remained victorious and managed to get Denmark-Norway (1700) and Saxony-Poland (1706) eliminated from the war. When he was preparing to defeat Russia in a final campaign from 1708, the Swedes suffered a devastating defeat in the Battle of Poltava in July 1709, which marked the turn of the war.

Encouraged by this defeat of their former adversary, Denmark and Saxony rejoined the war against Sweden. From then until the end of the war, the Allies retained the initiative and put the Swedes on the defensive. The war, which had become hopeless for his country, was only ended after the Swedish king, who was regarded as unreasonable and obsessed with war, fell during a siege off Frederikshald in Norway in autumn 1718 . The terms of the peace treaties of Stockholm , Frederiksborg and Nystad meant the end of Sweden as a major European power and the simultaneous rise of the Russian Empire, founded by Peter I in 1721 .

prehistory

Swedish rise to great power

The pursuit of the Dominium maris Baltici , that is, rule over the Baltic Sea area, was the trigger for many armed conflicts between the Baltic Sea countries even before the Great Northern War (cf. Northern Wars ). The causes of the Great Northern War were diverse. In numerous wars against the kingdoms of Denmark (seven wars) and Poland-Lithuania (five wars) as well as the Russian tsarist empire (four wars) and a war against Brandenburg-Prussia , Sweden, which was mostly victorious, was able to achieve supremacy in the Baltic Sea region by 1660 and defend it from then on.

As the guarantor of the Peace of Westphalia , Sweden officially rose to become a major European power in 1648, after it had already denied access to the Baltic Sea from the Tsarist Empire in the Treaty of Stolbowo in 1617 . However, Sweden's newly won European great power position in the Thirty Years War was on a weak foundation. The Swedish heartland (essentially today's Sweden and Finland) had only a comparatively small population of barely two million inhabitants and thus only about a tenth to a fifth of the inhabitants of the other Baltic Sea countries (the Holy Roman Empire , Poland-Lithuania or Russia ). The Swedish heartland had a narrow economic base. The great power of Sweden was based to a decisive extent on the extraordinary clout of its army. To finance them, Sweden relied heavily on sources of income such as For example, the port tariffs of large Baltic ports such as Riga (the largest city in the Swedish Baltic region), Wismar or Stettin (in Swedish Pomerania ) as well as river tariffs on the Elbe and Weser rivers.

The Second Northern War began in 1655 and ended with the Peace of Oliva in 1660. In this war, Charles X Gustav forced the Polish king John II Casimir , who was a great-grandson of King Gustav I of Sweden and the last living Vasa , to renounce the Swedish royal throne and Denmark to give up unrestricted rule over the sound . As in the Thirty Years' War, Sweden was supported by France in terms of foreign policy and subsidy payments in the following years and was thus able to preserve its property.

Sweden in particular had to fear the post-war situation, because the revision tendencies of the neighbors Denmark, Brandenburg, Poland and Russia affected by Sweden's expansion had hardly remained hidden during the peace negotiations. The legacy of the warlike era of the rise of great power for the peaceful period of securing great power after 1660 remained difficult. H. Sweden was still in a very unfavorable position in terms of its structural prerequisites for maintaining a large military potential in its own country. After the defeat against Brandenburg-Prussia in 1675 at Fehrbellin , Sweden's precarious situation also became evident abroad. For this reason, King Charles XI called. in 1680 the Reichstag. Important reforms in the state and military were initiated: with the help of the peasants, the citizens, the officers and the lower nobility, the repatriation of the former crown lands was enforced by the nobility, the Imperial Council was relegated to the advisory Royal Council, the legislation and foreign policy, the had been at the Reichstag until then, taken over by the king. The king became an absolute absolute ruler. After the political reforms, Charles XI. carried out an extensive and overdue reorganization of the military . His son and successor Karl XII. left behind Charles XI. 1697 a reformed absolutist great power state and a reorganized and efficient army.

Formation of a triple alliance

It was part of Swedish diplomacy to control Denmark and Poland through contractual reinsurance with Russia in such a way that encirclement could be avoided. In the following period could Diplomacy of Bengt Oxenstierna the danger of encirclement not ban longer.

At the end of the 17th century the following lines of conflict emerged in Northeastern Europe: Denmark had relegated from its position as the dominant state of Scandinavia to a middle power with limited influence and saw control of the remaining Baltic accesses at risk. Although the customs duties on foreign ships were the main source of income for the kingdom, the danger of outside interference was always present. A point of contention between Denmark and Sweden was the question of Gottorf's shares in the duchies of Holstein and especially Schleswig . In 1544 the duchies were divided into royal, gottorfian and jointly ruled shares. Holstein remained an imperial and Schleswig Danish fiefdom . After the Peace of Roskilde in 1658, the shares of the Gottorfer allied with the Swedes in the Duchy of Schleswig were released from Danish feudal sovereignty. Danish foreign policy, which saw itself threatened from two sides by the Gottorf alliance with the Swedes, tried to re-incorporate the lost territories. The independence of the partial duchy of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf was only guaranteed by the Swedish government, which assumed that it would have a strategic base for troop deployments and attacks on the Danish mainland in the event of a war against Denmark. Another point of contention between Denmark and Sweden was the provinces of Schonen (Skåne) , Blekinge and Halland , which had historically been core countries of the Danish state, but had belonged to Sweden since the Peace of Roskilde in 1658. In these newly won provinces, Sweden rigorously suppressed all pro-Danish endeavors. The dispute over the state membership in Skåne had already led in 1675 to Denmark's ultimately unsuccessful entry into the Northern War from 1674 to 1679 .

In Russia, Tsar Peter I (1672–1725) opened his country to Western Europe. In his opinion, the prerequisite for this was free access to the world's oceans. Sweden dominated the Baltic approaches and the mouths of the Neva and Narva rivers in the Baltic States . As an inland sea, the Black Sea offered only limited access to the world's oceans, as the Ottoman Turks controlled its exit on the Bosporus. Russia was only able to enter into maritime trade with the rest of Europe via the Arctic Ocean port of Arkhangelsk . Although Russia had mineral resources, furs and raw materials, the country could not trade profitably with the West without a suitable sea route.

Elector Friedrich August I of Saxony (1670–1733) was elected King of Poland (and thus also ruler of Lithuania, see Saxony-Poland ) in 1697 as August II . Since the nobility had a great influence on the decisions in the Polish-Lithuanian dominion, August II strove to gain recognition, to shift the balance of power in his favor and to convert the kingship into a hereditary monarchy. He was advised by Johann Reinhold von Patkul (1660–1707), who had fled from Swedish Livonia . He said that the reconquest of the once Polish Livonia would give August some prestige. The Livonian nobility would welcome this move and rise against Swedish rule. Under King Charles XI. of Sweden (1655–1697) the so-called reductions had come about , through which part of the land held by the nobility was transferred to the crown. This practice met with resistance from the Baltic German nobility, especially in Livonia , whose leaders then sought foreign aid.

Soon after the accession to the throne of the only 15-year-old Charles XII. of Sweden (1682–1718) formed an alliance. In the first year of his reign, the young king had made his brother-in-law Friedrich IV (1671–1702), the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, commander-in-chief of all Swedish troops in Germany and commissioned him to improve the national defense of the Gottorf sub-duchy. These obviously military preparations gave the impetus for the first alliance negotiations between Saxony-Poland and Russia in June 1698. In August 1698, Tsar Peter I and King August II met in Rawa , where they made the first arrangements for a joint attack on Sweden. At the instigation of Patkul it finally came on November 11th July. / November 21, 1699 greg. with the Treaty of Preobrazhenskoe for a formal alliance between Saxony-Poland and Russia. On November 23rd, Jul. / December 3rd greg. Another alliance between Tsar Peter I and King Frederick IV of Denmark (1671-1730) was concluded. Denmark had been allied with Saxony in a defensive alliance since March 1698. However, neither of the treaties explicitly mentioned Sweden as an objective of these agreements. They merely obliged the contracting parties to provide assistance in the event of an attack or if the trade of one of the countries was impaired by other countries. Furthermore, Tsar Peter had clauses inserted according to which he was only bound to the provisions of the treaties after a peace agreement between Russia and the Ottoman Empire (→ Russo-Turkish War (1686–1700) ).

Defense against the Allied attack on Sweden (1700)

Saxon and Danish attacks

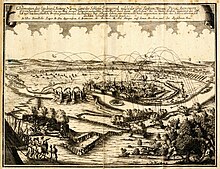

On February 12, 1700, General Jacob Heinrich von Flemming, at the head of around 14,000 Saxon soldiers, invaded Livonia to take the province and its capital, Riga . The Governor General of Livonia was Field Marshal Count Erik von Dahlberg , who was also Sweden's most famous fortress builder and who put his capital in an excellent state of defense. In view of Riga's strong walls, the Saxons first took the neighboring Dünamünde (March 13-15, 1700), which was immediately renamed Augustusburg by August II . Then the Saxon troops set up a blockade in front of Riga, but without seriously attacking the fortress. After eight weeks, however, Dahlberg's Swedes took the initiative and defeated the Saxons in the battle at Jungfernhof (May 6, 1700). The Saxon troops evaded behind the Düna and initially waited for reinforcements. When she arrived in June 1700 under General Field Marshal Adam Heinrich von Steinau , August II personally accompanied her. Steinau went on the attack again in July, defeated a Swedish detachment under General Otto Vellingk near Jungfernhof and began the actual siege of Riga . When the siege made little progress, the Saxon side decided to secure larger parts of Livonia first. For this reason, Kokenhusen Castle was besieged in autumn and captured on October 17, 1700. Then the Saxons went to their winter quarters in Courland . The Swedish troops in Livonia were mainly recruited from Estonians , Latvians and Finns and were initially on their own. However, they benefited from the fact that the Livonian nobility did not rise up against Swedish rule. Instead, there were peasant revolts in the course of the Saxon invasion, which made the nobles all the more lean towards the Swedish crown.

In the meantime, on March 11, 1700, King Frederick IV of Denmark had also declared war on Sweden. A Danish corps of 14,000 men had already been assembled on the Trave under the command of Duke Ferdinand Wilhelm von Württemberg . These troops set off on March 17, 1700, occupied several places in Holstein-Gottorf and on April 22, 1700 enclosed Tönning . During the siege of Tönning , the city was bombarded with grenades from April 26th. Meanwhile only two cavalry regiments, the naval regiment and two battalions of infantry remained on Zealand . The protection of the Danish core areas against Sweden was assigned as the main task of the Danish fleet, which set sail with 29 ships of the line and 15 frigates in May. She was commanded by the young Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve and had the task of supervising the Swedish fleet in Karlskrona ; should the Swedes set course for Danish territory, the order was to attack them immediately. In May 1700, however, a Swedish army gathered from the regiments in Swedish-Pomerania and Bremen-Verden , which was under the command of Field Marshal Nils Karlsson Gyllenstierna . From the summer this was also supported by a Dutch - Hanoverian relief corps. The troops united at Altona and hurried to relieve Tönning. The Duke of Württemberg then gave up the siege of the city on June 2 and avoided a battle against the Swedish troops.

Swedish counter-offensive in Zealand

In the first phase, Sweden was largely able to determine the events of the war due to its initial successes. Central theaters of war were primarily Saxony-Poland , the up to then Swedish Livonia and Estonia, which the Russian tsarist army conquered in a separately waged side war until 1706.

In Sweden meanwhile the war readiness of the army and the navy was established. Around 5,000 new sailors were recruited, bringing the strength of the fleet under Admiral Hans Wachtmeister to 16,000 men. In addition, all merchant ships in Swedish ports were requisitioned for the upcoming troop transports. Sweden had a total of 42 ships of the line in the Baltic Sea compared to a total of 33 Danish. The army was rearmed up just as quickly. According to the system of division , the regional regiments were mobilized and a large number of new units were set up for this purpose. In total, the troops soon comprised 77,000 men. Sweden received further support in June from an Anglo-Dutch fleet of 25 ships of the line under the admirals George Rooke and Philipp van Almonde . The naval powers were concerned about the imminent death of the Spanish king, who was expected to lead to a war of European succession . In view of this uncertain situation, they were not prepared to allow their important trade and supply routes in the Baltic Sea to be jeopardized by a Danish-Swedish war. For this reason they had decided to stand by Sweden against the attacker Denmark.

In mid-June 1700, the Anglo-Dutch squadron was in front of Gothenburg , while Charles XII. set sail with the Swedish fleet in Karlskrona on June 16. The Danish fleet lay between the allies in the Oresund to prevent their opponents from uniting. However, Karl let his fleet take a narrow fairway along the eastern bank and soon reached the allied ships. Together, the allies now had more than 60 ships and were almost twice as superior to the Danish fleet. The Danish admiral Gyldenløve therefore decided to avoid a sea battle and withdrew. Now, on July 25, the first Swedish troops were able to land on Zealand under the protection of their naval guns. At the beginning of August 1700 they already had about 14,000 men compared to fewer than 5,000 Danish soldiers. They quickly succeeded in enclosing Copenhagen and bombarding it with artillery. King Frederick IV had lost command of the sea, and his army was far to the south in Holstein-Gottorp, where the fighting was also unfavorable for him. He had no other option but to communicate with Karl. On August 18, 1700, the two rulers concluded the Peace of Traventhal , which restored the status quo ante .

Narva campaign

Originally, the Allies had agreed that Russia should open war against Sweden as soon as peace was concluded with the Ottoman Empire, but if possible in April 1700. But the peace negotiations dragged on and Peter I hesitated, despite the urging of August II to join the war. An understanding was only reached with the Ottomans in mid-August 1700, and on August 19 Peter I finally declared war on Sweden. However, he did so in complete ignorance of the fact that the day before, Denmark, an important ally of the coalition, had already ceased to exist. In a report on September 3, the Dutch envoy therefore stated: “If this news had arrived a fortnight earlier, I very much doubt whether S. Czarian's Majesty would march with her army or his Majesty the King of Sweden Would have declared war. "

from: Johann Christoph Brotze : Collection of various Liefländischer monuments

However, as early as the summer of 1700, Peter I had an army set up on the Swedish borders, which largely consisted of young recruits trained on the Western European model. Overall, the armed forces were divided into three divisions under Generals Golowin , Weide and Repnin . Another 10,500 soldiers of the Cossack army joined these , so that the total armed forces amounted to about 64,000 men. Of these, however, a large part was still in the interior of the country. A Russian vanguard entered Swedish territory in mid-September, and on October 4, 1700, the main Russian army began the siege of Narva with around 35,000 soldiers . Before the war, Peter I had claimed Ingermanland and Karelia for himself in order to get safe access to the Baltic Sea. Narva was only 35 kilometers from the Russian borders, but in Livonia, which was claimed by August II. The allies therefore distrusted the tsar, and they feared that he wanted to conquer Livonia for himself. However, there were three reasons in favor of Narva as the target of the Russian attack: It was south of Ingermanland and could serve as a gateway for the Swedes into this province. It was not far from the Russian borders and was therefore a relatively easy-to-reach destination from a logistical point of view. Last but not least, it was important that almost all of Russia's trade to the west ran via Riga and Narva and that the Tsar would not have liked to see both cities in the possession of August II.

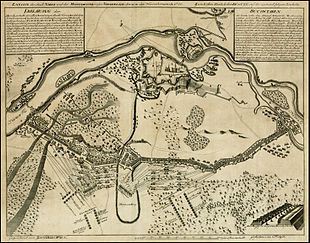

Fortifications, troop movements, batteries of the Battle of Narva drawn by Zacharias Wolf .

Meanwhile, Charles XII. his army withdrew from Denmark by August 24, 1700. Since then he has been preparing an expedition to Livonia in southern Sweden to face the Saxon troops there. Despite the impending autumn storms, Karl left Karlskrona on October 1st and reached Pärnu on October 6th . The Swedish associations suffered losses from violent storms. Nevertheless, the fleet was immediately sent back to transfer more soldiers and the heavy artillery. Since he found the old Dahlberg victorious in Riga and the Saxons were already in their winter quarters, he decided to turn against the Russian army at Narva. He moved his troops to Reval , where he gathered further reinforcements from the region and had his units drilled for several weeks. On November 13, 1700, he set out east with around 10,500 soldiers. The march in cold weather and almost without any supplies turned out to be difficult, but on November 19th the Swedes reached the Russian positions. The following day the battle of Narva ((20) November 30, 1700) finally took place , in which the Swedish troops defeated the outnumbered Russian army. In the course of the fighting and during the subsequent escape, the Russian army almost completely disintegrated and practically lost all of its artillery. However, the few Swedish forces were also weakened, and after Narva had been liberated, they too had to move into their winter quarters first.

War of dethroning against August II (1701–1706)

At the end of 1700 Charles XII. Sweden successfully defended and all enemy troops driven from Swedish territory. Instead of pursuing the defeated Russian army in order to destroy it completely and forcing his opponent, Tsar Peter I, to make peace as well, the king now turned to his third opponent, the Saxon Elector and King of Poland, to give him the Polish royal throne to snatch. There has been much speculation about the exact motives of the Swedish king, and this decision of his has been almost unanimously criticized by later military historians as a serious mistake, since the chance to finally destroy the defeated Russian army and thus force Russia to peace was wasted. Decisive for the turn in the direction of Poland were probably above all personal motives of Charles XII. As a staunch Lutheran, the Swedish king harbored a personal hatred of August the Strong, as he had deviated from the Lutheran faith of his ancestors for reasons of power calculation and converted to Catholicism in order to be able to become King of Poland. In addition, Charles XII saw. in August the Strong the real warmonger against Sweden. The Livonian aristocratic opposition to the Swedish crown under Reinhold von Patkul relied primarily on Polish-Saxon support. In addition, the Swedish king fatally underestimated Russia's military potential and believed that, as with Narva in 1700, he could defeat the Russian army anew at any time. Karl considered the military development in the Baltic States to be of secondary importance.

The King of Sweden turned south with his main army and in the following 5 years of the war of dethronement passed through almost all of Polish territory. In addition, there were further battles for rule in Courland and Lithuania between Swedish troops under the command of Lewenhaupt and Russian units. The two theaters of war in the Baltic States and Poland only overlap in 1705, when a Russian army, which marched into Courland in 1705, defied the approaching Charles XII. had to withdraw without leading to an open battle. In years of campaigns, Karl spent himself with the Swedish army in Poland and Saxony, while Swedish Livonia was devastated by Russian armies. The war in Poland did not end until 1706 with the Peace of Altranstadt , in which August II was forced to renounce the Polish throne.

Occupation of the Duchy of Courland

August II was now preparing for the Swedish offensive to be expected in the new year. The refusal of his Polish subjects to support the war financially and with troops turned out to be disadvantageous. The Polish Sejm of February 1701 only obtained the support of August from a small auxiliary corps of 6,000 Poles and Lithuanians, too little for the upcoming fight against Karl. In response to the Swedish successes, August II and Peter I met in February 1701 in a completely different situation to renew their alliance. Peter needed time to reorganize and arm the Russian tsarist army . August needed a strong ally in the rear of the Swedes. Tsar Peter promised to send 20,000 men to the Daugava so that August could dispose of an army of 48,000 men from Saxony, Poland, Lithuanians and Russians to repel the Swedish attack in June 1701. Under the impression of the Swedish successes, both allies sought to leave the war for themselves: regardless of their agreement and without the knowledge of the other, they offered the Swedish king a separate peace. Charles XII. however, did not want peace and prepared more for the planned campaign against Poland. To this end, he had a total of 80,492 men deployed for 1701. 17,000 men were deployed to cover the interior of the country, 18,000 men protected Swedish Pomerania, 45,000 men were distributed across Livonia, Estonia and Ingermanland. Most of the Swedish troops in Livonia were concentrated around Dorpat .

After the usual army demonstrations , the Swedish advance to Riga via Wolmar and Wenden began on June 17, 1701 . Karl planned to move his army across the Daugava between Kokenhusen and Riga. The Saxons had suspected this approach and built field fortifications at several transition positions along the Düna. Both armies met for the first time on July 8th . / July 19, Greg. near Riga on the Daugava river. The Saxon-Russian army with 25,000 men was slightly superior to the army of around 20,000 Swedes. This advantage was lost, however, as the Saxon commander-in-chief Adam Heinrich von Steinau was deceived by Swedish diversionary maneuvers and his units split up along the Daugava. So the Swedish infantry managed to cross the wide river and form a bridgehead on the river bank held by the Saxons. The Saxon army suffered a defeat in the ensuing battle on the Daugava , but was able to rally and withdraw in an orderly manner, except for Prussian territory. The Russian troops also withdrew to Russia, shocked by the renewed defeat. The whole of Courland was open to the Swedish army. Charles and his victorious troops occupied Mitau , the capital of the Duchy of Courland , which was under Polish suzerainty .

Conquest of Warsaw and Krakow

The Polish-Lithuanian Republic protested against the violation of Polish territory through the advance of the Swedes into Courland, because not the republic (represented by the Sejm ) was at war with Sweden, only the King of Poland. When August the Strong offered to negotiate again, the advisers recommended to Charles XII that peace be made with the King of Poland. The governor-general of Livonia, Erik von Dahlberg, went the furthest, and eventually even submitted his resignation in protest against his king's war plans. But Karl remained uncompromising and asked the Sejm to elect a new king. However, this was rejected by the majority of the Polish nobility.

In January 1702, Karl moved his army from Courland to Lithuania. On March 23, 1702 the Swedes left their winter quarters and invaded Poland. Without waiting for the planned reinforcements from Pomerania, Karl marched with his army directly against Warsaw , which surrendered on May 14, 1702 without a fight. The Polish capital was forced to pay a large contribution before Charles continued his march to Krakow . The fear that Sweden would seek territorial gains in Poland in a conceivable peace treaty prompted the Polish nobility to take part in the war.

Before Charles XII. Occupied Warsaw, August II had moved to Cracow with the Polish Crown Army, some 8,000 men strong, in order to unite with the 22,000 strong Saxon army that had been newly established in Saxony. The Polish crown army under Hieronim Augustyn Lubomirski was poorly equipped, poorly cared for and little motivated to fight for the cause of the Saxon king. When the 24,000–30,000 strong Polish-Saxon army south of Kielce opposed the Swedes, who numbered only 12,000, this situation made it easier for the Swedes on July 8th . / July 19, Greg. an all-round victory in the battle of Klissow . 2,000 Saxons were killed or injured, and another 700 were taken prisoner by Sweden. The Swedes captured 48 cannons and had 300 dead and 800 injured themselves. They also captured the entire entourage as well as August's field treasury with 150,000 Reichstalers and his silver dishes. However, the low troop strength of the Swedes did not allow the defeated Polish-Saxon army to be pursued, and so August was able to regroup the remaining units of his army in the eastern parts of Poland. His quick retreat via Sandomierz to Thorn allowed Karl to occupy Krakow on July 31, 1702. Sweden now controlled the royal seat of Warsaw and the coronation city of Krakow. However, over half of the Polish Empire remained in the hands of August II.

War in Courland and Lithuania

In addition to the war events in Poland, fighting for supremacy in the Baltic States also took place in Courland and Lithuania. The victors of the previous Lithuanian-Belarusian civil war, the Oginski, had removed the sapieha from all state offices by decree. The defeated former rulers now allied themselves with the victorious Swedes, while the Oginski or Count Grzegorz Antoni Ogiński called Peter I for help. Peter I signed an agreement with the Oginskis on military aid in 1702. Another violent civil war broke out. After the march, the main army under Charles XII was to protect Courland. a Swedish corps was left behind in January 1702 under the command of Carl Magnus Stuart . Due to a non-healing wound, however, he left the actual command of the troops to Colonel Count Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt . In Lithuania, under the command of Generals Carl Mörner and Magnus Stenbock, there was another Swedish division of several thousand men, which in June 1702 were largely Charles XII. followed, leaving only a small force behind.

While the Sapieha allied with Sweden organized peasant troops who fought against the Oginski Confederation in the Belarusian Dniepr region , they devastated the Sapieha lands with Russian support. When the Sapiehas temporarily withdrew from Lithuania after the Swedes withdrew, Ogiński took advantage of the situation and attacked the Swedish troops in Lithuania and Courland from May to December 1702. His goal was to conquer the Birze fortress as a starting point for further ventures. In one of his attempts, Ogiński's army of 2,500 Russians and 4,500 Poles provided a 1,300-strong Swedish detachment that had been sent to relieve the fortress. On March 19, 1703, the defeated Swedish division defeated the Russian-Polish army in the battle at Saladen . Ogiński then withdrew to Poland to unite with August's troops.

Swedish conquest of western and central Poland

After the defeat at Klissow on July 19, 1702, August II had again offered the Swedes peace negotiations. He wanted to meet the Swedish demands as far as possible, with the sole aim of being able to remain King of Poland. Michael Stephan Radziejowski , Cardinal Archbishop of Gniezno and Primate of Poland-Lithuania, also made proposals for peace on behalf of the Republic of Poland. He offered Charles XII. Polish Livonia , Courland and high war compensation. Karl would only have had to forego the deposition of the king, which he was not prepared to do. So the war went on. After a delay of several weeks due to a broken leg, the Swedes continued their advance along the Vistula. At the end of the autumn of 1702, Karl moved his troops to winter quarters at Sandomierz and Kazimierz near Cracow.

Forced to continue the war, August II had to build up an army again to stop the Swedish advance. He held a Sejm in Thorn , at which 100,000 men were promised to him. To raise the money for this, he traveled to Dresden in December.

In the first months of 1703 the war ceased. It was not until March that Charles XII broke. with his army in the direction of Warsaw, which he reached at the beginning of April. At the beginning of April 1703 August II left Dresden to start a new campaign from Thorn and Marienburg. He had used the time to raise a new Saxon-Lithuanian army. When Karl learned that the enemy army was encamped at Pułtusk , he left Warsaw and crossed the Bug with his cavalry . On April 21, 1703, the Saxons were completely taken by surprise in the Battle of Pułtusk . The victory cost the Swedes only 12 men, while the Saxon-Lithuanian army had to endure several hundred dead and wounded as well as 700 prisoners. After the defeat at Pułtusk, the Saxons were too weak to face the Swedish army in the open field. They withdrew to the fortress of Thorn. Charles XII. then moved north to destroy the last of the demoralized Saxon army. After months of siege of Thorn , he took the city in September 1703. The Swedes captured 96 cannons, 9 mortars , 30 field snakes , 8,000 muskets and 100,000 thalers. Several thousand Saxons were taken prisoner of war. The capture of Thorn gave King Charles complete control of Poland. In order to rule out any future resistance from the city, which had defied the Swedes for six months, its fortifications were razed. On November 21st, the Swedes left Thorn for Elblag . The chilling example had the desired effect, and under the impression of the war glory that was ahead of it, many other cities submitted to the Swedish king in order to be spared in return for paying high tributes. Shortly before Christmas, Karl had his army move into winter quarters in West Prussia , as this area had so far remained untouched by the war.

The confederations of Warsaw and Sandomir

After the catastrophic campaigns of 1702 and 1703, August II's military position became hopeless, his financial resources were exhausted and his power base in Poland began to crumble. Under the influence of the country's economic decline, the Polish nobility split into different camps. In 1704 the Confederation of Warsaw , which was friendly to Sweden, was founded and pushed for an end to the war. It was joined by Stanislaus Leszczyński , who led the peace negotiations with the Swedes from 1704. As he gained the trust of their king, Charles XII saw. in Stanislaus soon the suitable candidate for the planned new election of the Polish king.

In Saxony, too, there was resistance to the Elector's Polish policy. August introduced an excise tax to fill his war chest and arm the army. That turned the Saxon estates against him. He also aroused public resentment through aggressive recruiting methods. With Russian support, however, he succeeded in raising an army of 23,000 Saxons, Cossacks and Russians. Lithuania, Volhynia , Red Russia and Lesser Poland continued to be loyal to the Saxon king, so that August and his court were able to retreat to Sandomierz . There, parts of the Polish nobility had formed a confederation to support them, which turned against the Swedish occupation of Poland and the new king demanded by Sweden. The Sandomir Confederation under the hetman Adam Mikołaj Sieniawski refused to recognize August's abdication and Stanislaus Leszczynski's accession to the throne. However, this did not mean a real balance of forces, because the confederation was of little military importance, and its troops could at best disrupt the supply of the Swedes. Tsar Peter concluded an agreement with August II that enabled him to continue the war against Sweden in Poland-Lithuania. In the autumn of 1704 a large Russian army then moved to Belarus , which remained stationed in Polotsk for a long time and then took Vilna , Minsk and Grodno.

Election of a new King of Poland loyal to Sweden

At the end of May 1704, Charles XII broke. from his winter quarters to Warsaw to protect the planned royal election. The army consisted of 17,700 infantry and 13,500 cavalry. After Charles's arrival in Warsaw, Stanislaus I. Leszczyński was elected king on July 12, 1704, against the will of the majority of the Polish nobility , under the protection of the Swedish army .

After the election, Karl took a strong army corps against the breakaway territories that refused to obey the new king. August did not recognize the election and avoided the advancing Karl with his army. When the Swedish army advanced to Jarosław in July , August took the opportunity to move back to Warsaw. Instead of pursuing him, Karl captured poorly fortified Lemberg in an assault at the end of August . In the meantime August had reached Warsaw, where the newly elected king was staying. In the city itself there were 675 Swedes and around 6000 Poles who were supposed to protect the king who was loyal to Sweden. Most of the Polish soldiers deserted, and the Polish king also fled the city, so that only the Swedes resisted. On May 26, 1704, the Swedish garrison had to surrender to August II. After taking Warsaw, August moved to Greater Poland. The weak Swedish contingent there then had to withdraw.

At Lemberg Karl received the news that Narva had been taken by Russian troops. However, he still ruled out a move to the north. With a two-week delay, the Swedish army returned to Warsaw in mid-September to recapture the city. August did not let it come down to a fight, but fled before the arrival of Charles from his capital and transferred the command of the Saxon army to General Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg . Even this did not dare open field battle and withdrew to Posen , where a Russian contingent under the command of Johann Reinhold von Patkul had enclosed the city. After the renewed conquest of Warsaw, Karl had the Saxon-Polish army persecuted. A Russian detachment of 2,000 men was defeated in one battle, 900 Russians were killed. The remaining Russians fought almost to the last man the following day. Despite the skilful retreat of the Saxons under Schulenburg, Karl caught up with part of the Saxon army shortly before the Silesian border. In the Battle of Punitz , 5000 Saxons withstood four attacking Swedish dragoon regiments. Schulenburg managed to withdraw his troops in an orderly manner across the Oder to Saxony. Because of the strenuous marches, Karl had to move into his winter quarters at the beginning of November. For this purpose, he selected the Wielkopolska district bordering on Silesia, which had been largely spared from the war until then.

Development in Courland and Lithuania

After Lewenhaupt's victory in the previous year, Jan Kazimierz Sapieha returned to Lithuania in the spring of 1704 and strengthened Lewenhaupt's position there. After the election of Leszczyński as the new Polish king, Lewenhaupt had from Charles XII. received the order to enforce the claims of the Sapiehas in their homeland. Lewenhaupt invaded Lithuania with his troops from Courland, whereupon the supporters of August II had to withdraw under the leadership of Count Ogiński. Lewenhaupt was able to pull the Lithuanian nobility over to the Swedish side and persuade the Lithuanian state parliament to pay homage to the new Polish king, but afterwards he had to return to Mitau because a Russian army was approaching and threatening Courland.

The Russian army united with loyal Polish troops and moved to the fortress Seelburg on the Daugava River , which was only occupied by a small garrison of 300 Sweden. Lewenhaupt rushed to relieve the besieged fortress. The Russian-Polish army then broke off the siege in order to oppose the approaching enemy. On July 26, 1704, the two armies met at Jakobstadt , where the numerically outnumbered Swedish-Polish army with 3,085 Swedes and 3,000 Poles defeated a numerically superior army of 3,500 Russians and 10,000 Poles in the battle of Jakobstadt . The Russian troops had to withdraw. From the battlefield near Jakobstadt, Lewenhaupt first turned towards the Birze fortress between Riga and Mitau, which had been occupied by Ogiński's troops. The crew of the fortress, consisting of 800 Poles, surrendered immediately and received free retreat. Lewenhaupt released his troops into winter quarters for the rest of the year, which also gave the war in Lithuania and Courland a break.

Coronation of the loyal king in Warsaw

In Poland there were no military events in the first half of 1705. The Swedish army under Charles XII. camped idly in the town of Rawitsch , which was also the headquarters of the Swedes in Poland. It was decided that Stanislaus Leszczyński, elected the previous year, should be crowned King of Poland in July 1705. For the Swedes, securing the succession to the throne was so important because the peace negotiations that had already started with Poland could only be concluded with their preferred candidate. The previous King August II was also ready to negotiate peace, but with the hope of a more docile candidate on the Polish throne for their purposes, the Swedish position hardened until the Swedes saw the dethronement of the Wettin as the only possibility of peace close to their senses.

Unlike the Swedes, August II did not remain idle and, with Russian support, was able to raise an army again to prevent the coronation of the Swedish rival king. At the suggestion of Johann Patkuls, he appointed his Livonian compatriot Otto Arnold Paykull as commander , who advanced to Warsaw with 6,000 Poles and 4,000 Saxons. To ensure the safety of the heir to the throne, Charles XII. Sent Lieutenant General Carl Nieroth with 2,000 men to the capital. On July 31, 1705, both armies met near Warsaw in the Battle of Rakowitz , in which the Saxon-Polish army was defeated by the five times smaller Swedish army. Lieutenant General Paykull and his diplomatic correspondence fell into the hands of the Swedes and was taken to Stockholm as a prisoner of state. There he impressed his judges by claiming that he knew the secret of making gold . But although he took a sample of his alchemical art, Charles XII held. the matter was not worth further investigation and had him beheaded for treason .

As a result of the battle, Stanislaus Leszczyński was crowned the new Polish king in Warsaw on October 4, 1705 . But he remained militarily and financially completely dependent on his Swedish patrons and was still not recognized in all parts of the country. Only Greater Poland , West Prussia , Mazovia and Lesser Poland submitted to him, while Lithuania and Volhynia continued to support August II and Peter I. As a direct result of the royal coronation, the Kingdom of Poland concluded the Warsaw Peace with Sweden in the person of Leszczyński on November 18, 1705 . The previous king of the country and Elector of Saxony, August II, did not accept this peace and declared that only between Sweden and Poland there would no longer be war, but still between Sweden and the Electorate of Saxony.

The war also continued in Courland and Lithuania. Due to Levenhaupt's successes in the previous year, Peter I had commissioned his Marshal Sheremetyev to cut off Levenhaupt's 7,000-strong army with a 20,000-strong army. For this purpose, the advance had to be kept secret for as long as possible in order to prevent the concentration of the opposing forces. However, this did not succeed, so that Lewenhaupt was able to gather his troops in time. On July 16, 1705, Lewenhaupt and his entire army took up battle formation against the advancing Russian army. After four hours of fighting, the Swedes won the Battle of Masonry with a loss of 1,500 men, while the outnumbered Russian army lost 6,000 men. The victory of the Swedes did not last long, however, because in September Peter sent another army, this time 40,000 strong. This time the tsar only allowed his army to march at night in order to keep the operation secret for as long as possible. Nevertheless, Swedish scouts learned of the recent Russian advance, so that Levenhaupt, promoted to lieutenant general, was able to gather his troops in and around Riga. After Peter I had been informed of this, he directed the planned advance towards the smaller fortresses of Mitau and Biskau instead of Riga . Since all Swedish troops were around Riga, all of Courland could be occupied by Russian troops.

Fight for recognition of the new king

For the first time since the Battle of Narva, Charles XII marched. with the Swedish main army in the Baltic States to help the Swedish forces oppressed there. The starting point was Warsaw, where he had stayed for the entire autumn of 1705. Karl decided to force the still breakaway territories to swear allegiance to the new king. At the end of 1705 the army began to advance across the Vistula and the Bug to Lithuania. In the autumn, Swedish reinforcements from Finland had brought Lewenhaupt's army, which had been concentrated in Riga, to a strength of 10,000 men. The Russian forces in Courland feared that they would be pinned down by Levenhaupt's troops in Riga and the advancing Karl. After the fortifications in Mitau and Bauske were blown up, they initially withdrew from Courland to Grodno, so that Lewenhaupt was able to occupy Courland again. After the Russians had withdrawn, the Lithuanians began to move more and more over to the new King of Poland, loyal to Sweden, which considerably reduced the burdens of the war for them. There was also a reconciliation of the warring Lithuanian noble families of the Sapiehas and the Wienowickis. Since Count Ogiński achieved no success anywhere with his continued struggle on the side of August II, the Swedish party in Lithuania finally won the upper hand.

On January 15th (July) the army of Charles XII crossed on the way to Grodno den Nyemen , where a 20,000-strong Russian army was under Field Marshal Georg Benedikt von Ogilvy . This had crossed the Polish border in December 1705 to unite with the Saxon troops. Karl had gone against the Russians with the main part of his army of almost 30,000 men, but there was no battle because the Russian troops did not want to engage in a confrontation with the Swedish king and retreated to Grodno . Because of the cold, a siege was out of the question, so Karl only had a blockade ring built around Grodno, which cut off the city and the Russian army from the supply of supplies.

When August II saw that Charles XII. was idle in front of Grodno, he held a council of war , which decided to use the absence of the king to destroy a further west standing Swedish detachment under the command of Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld . This was left behind by Karl with over 10,000 men to protect Greater Poland and Warsaw. August wanted to move west, on the way to unite with all Polish detachments and then with the newly established Saxon army in Silesia under the command of General Schulenburg in order to attack the corps of Rehnskiöld and march back to Grodno after a victory. On January 18, August bypassed the Swedish blockade to the west with 2,000 men, united with several Polish troop contingents, and on January 26 entered Warsaw for the second time . From there, after a short break, he advanced with his army, which had now grown to 14,000 to 15,000 men, to attack the Swedish corps. He also ordered General Schulenburg to take up the nearby Russian auxiliary corps of 6,000 men with his troops and march to Wielkopolska to unite with him. Rehnskiöld received news of the Saxon plan and hoped to avoid annihilation by engaging the enemy in combat while they were still separated. By pretending to retreat, General Schulenburg actually let himself be tempted to attack the outnumbered Swedes. Without reinforcement by August II's Polish army, Schulenberg's Saxon recruits suffered a crushing defeat by the storm-tested Swedes in the battle of Fraustadt on February 13, 1706. After this new setback, August II broke off his advance, sent some of the troops back to Grodno and marched with the rest to Cracow. The situation in Grodno became hopeless for the Russian army due to the defeat at Fraustadt. She could no longer hope for relief, and the supply problems had worsened dramatically. In addition to the famine, illnesses spread among the soldiers, which led to high number of failures. After the news of the defeat at Fraustadt in Grodno, the Russian commander Olgivy decided to break out to Kiev with the remaining 10,000 combat-capable men. They escaped the Swedish persecutors and were able to save themselves across the border.

Charles XII. had marched to Pinsk in pursuit of the Russian army . From there he left after a break on May 21, 1706 to move to the south of Poland-Lithuania. The areas there still lasted to August and refused an oath of allegiance to King Stanislaus I. On June 1, Karl entered Volhynia . There, too, the new king, loyal to Sweden, had been recognized with military force. There was also fighting during the summer months. Several forays by the Swedes along the Russian-Polish border against Russian positions did not produce any decisive results. Based on the experience of the campaigns through Poland, which had served the purpose of enforcing the legitimacy of the new king, who was loyal to Sweden, Karl began to reconsider his strategy. As long as the Swedish army was there, the residents took the forced oath of allegiance. As soon as the Swedish army had moved away, however, they turned back to King August, who kept bringing new troops in from his retreat in Saxony. Due to the ineffectiveness of his previous strategy, Karl now wanted to end the war by taking a train to Saxony.

Conquest of Saxony and abdication of King August II.

In the summer of 1706 Charles XII broke. with his troops from the east of Poland, united with the army of Rehnskjöld and advanced on August 27, 1706 via Silesia into the Electorate of Saxony . The Swedes conquered the electorate step by step and stifled all resistance. The land was rigorously exploited. Since the battle of Fraustadt, August had no more troops worth mentioning, and since his home country was also occupied by the Swedes, he had to offer Karl peace negotiations. The Swedish negotiators Carl Piper and Olof Hermelin as well as Saxon representatives signed a peace treaty in Altranstädt on September 24, 1706, but this could only become valid when ratified by the king.

Although August wanted to end the state of war, he was also bound by alliances to Peter I, from whom he kept the impending peace with Sweden a secret. In response to the news of the Swedes' advance into Saxony, the Russian army, led by Generals Boris Petrovich Sheremetev and Alexander Danilowitsch Menshikov, had advanced from the Ukraine far into western Poland. Menshikov led an advance command in front of the main parts of the Russian army and united in Poland with the remaining Saxon-Polish army under August II. Under Russian pressure, August had to officially continue the fight and rather reluctantly defeated the united, 36,000-strong army Battle against the Swedes at Kalisch . In the Battle of Kalisch , the combined Russian, Saxon and Polish troops were able to completely destroy the numerically inferior Swedish troops under General Arvid Axel Mardefelt, who had been left behind by Karl to defend Poland . General Mardefelt and over 100 officers (including Polish magnates ) were taken prisoner. However, this did not change anything in the continued superior power of Sweden, so that August refused to cancel the peace treaty and quickly returned to Saxony to seek a compromise with Karl. On December 19, the elector announced the ratification of the Altranstadt peace treaty between Sweden and Saxony, with which he renounced the Polish crown "forever" and dissolved the alliance with Russia. He also committed himself to extraditing prisoners of war and deserters, namely Johann Reinhold von Patkul. August the Strong had already arrested the Livonian who had advised him to go to war in December 1705. After his transfer to the Swedes, Karl XII. him as a traitor wheels and quartered .

For the Polish King Stanislaus Leszczyński, who was dependent on Sweden, the treaty did not improve his situation. He failed to involve his domestic enemies, and so he continued to rely on the protection of the Swedish troops.

The Swedish advance to Saxony in 1706/07 triggered international entanglements, because the occupation of an imperial territory was a clear breach of imperial law , especially since Charles XII. was an imperial prince himself through his possessions in Swedish-Pomerania and Bremen-Verden. Moreover, the Swedes had marched through Silesia , which was Habsburg territory, without being asked . Another imperial war could not be enforced due to the simultaneous war with France. From the point of view of the Viennese court, it was also important to prevent Charles from allying himself with the rebellious Hungarians or marching into the Habsburg hereditary lands and thus creating a new constellation as in the Thirty Years War .

The danger that the Great Northern War would mix with the parallel fighting in Central Europe in the War of the Spanish Succession was great at this point in time. Both warring sides therefore endeavored to win the King of Sweden as an ally or at least to keep him out of the conflict. In April 1707, for example, the Allied commander of the troops in the Netherlands, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough , visited the Swedish camp in Saxony. He urged Karl to turn east again with his army and not to advance further into the imperial territory. The Habsburg Emperor Joseph I also asked Karl to stay out of Germany with his troops. For this purpose, the emperor was even ready to recognize the new Polish king and to make concessions to the Protestant Christians in the Silesian hereditary lands, as they were finally agreed on September 1, 1707 in the Altranstadt Convention , in which, among other things, the permission to build so-called Gnadenkirchen was granted. Karl was not interested in interfering in German affairs and preferred to pull against Russia again.

War in the Swedish Baltic provinces (1701–1707)

Far away from the fighting in Poland, Russia gradually conquered the Swedish Baltic provinces after the defeat at Narva. Since the main Swedish army was tied up in Poland, far too few Swedish forces had to protect a large territory. Because of the numerical superiority of the Russians, they succeeded less and less. The Russian armed forces were able to get used to the Swedish war tactics relatively safely and develop their own war skills, with which they then inflicted a decisive defeat on Karl in the Russian campaign.

Russian war plans after the battle of Narva

Charles XII. After the victory in the Battle of Narva at the end of November 1700, his main army had moved south to fight August II. He transferred the supreme command of the Swedish Baltic Sea holdings to Major General Abraham Kronhjort in Finland , to Colonel Wolmar Anton von Schlippenbach in Livonia and to Major General Karl Magnus Stuart in Riga. The Swedish warships in Lake Ladoga and Lake Peipus were commanded by Admiral Gideon von Numers . At that time the Russian army was no longer a serious enemy. Because of the resulting certainty of victory, Karl turned down Russian peace offers. The tactical superiority of the Swedes over the Russians had also solidified as a prejudice in the thinking of Karl, who was so convinced of the minor importance of Russian clout that he concentrated his war efforts on the Polish theater of war even then, as a large part of Livonia and Ingermanland was under Russian control.

By shifting the main Swedish power to the Polish theater of war, however, the chances of Peter I to lead the war to a more favorable course and to conquer the desired access to the Baltic Sea for Russia increased. Tsar Peter took advantage of the withdrawal of the Swedish army and let the remaining Russian forces resume their activities in the Swedish Baltic provinces after the Narva disaster. The war strategy of the Russians was based on exhaustion of the enemy. This should be achieved through forays and constant attacks, combined with the starvation of the population through the destruction of the villages and fields. At the same time, the Russian soldiers were supposed to get used to the Swedish war tactics with their violent attacks in battle through the constant fight.

Tsar Peter used the time saved by the absence of the Swedish army to rearm and reorganize his army with enormous efforts. So he called foreign experts to train the troops - equipped with modern weapons - in the methods of Western European warfare. In order to quickly rebuild the artillery that was lost at Narva, he had church bells confiscated so that cannons could be poured from them. He had hundreds of gunboats built on Lake Ladoga and Lake Peipus . As early as the spring of 1701, the Russian army again had 243 cannons, 13 howitzers and 12 mortars. Reinforced by new recruits, it again consisted of 200,000 soldiers in 1705 after the 34,000 remaining in 1700.

In order to diplomatically support his war plans, the tsar had a negotiator sent to Copenhagen in parallel to the declarations of support to August II to persuade Denmark to invade Skåne . Since the Swedish Imperial Council had a force advance to the Sound , the alliance plans failed and the Danes postponed their attack until later.

The Swedish forces in the Baltic States under Colonel von Schlippenbach were only very weak and also separated into three autonomous corps. Each of these corps was too weak in itself to be able to counter the Russian forces successfully, especially since they were not led in a coordinated manner. In addition, these troops were not composed of the main regiments, but of newly recruited recruits. Swedish reinforcements were primarily sent to the Polish theater of war, so that one strategically important point after another could be captured by the Russian army.

Defeat of the Livonian army

After the withdrawal of their king with the main army, the Swedes initially remained offensive, at least as long as Russia was still weakened after the defeat of Narva. In order to shut down the only remaining Russian trading port in the White Sea , seven to eight Swedish warships made an advance from Gothenburg to Arkhangelsk in March 1701 . The company affected English and Dutch trade interests with Russia. Both nations reported the departure of the Swedish expedition fleet to their Russian partner. Peter then had the town strengthened its defense readiness. When the Swedish fleet reached the White Sea, two frigates ran into a sandbar and had to be blown up. The attack on Arkhangelsk did not promise success because of the precautionary measures Peter took, so that the fleet sailed home again after the destruction of 17 surrounding villages.

In mid-1701, first Swedish and then Russian forces carried out forays into Ingermanland and Livonia and marched into the opposing territory, where they fought several skirmishes . The Russian forces had recovered enough to be able to make limited offensives. From the Russian headquarters at Pskov and Novgorod , a force of about 26,000 men moved south of Lake Peipus to Livonia in September . In the subsequent campaign, the Swedish General Schlippenbach succeeded in September 1701 with a detachment of only 2,000 men to defeat the 7,000-strong Russian main army under Boris Sheremetyev in two meetings at Rauge and Kasaritz , with the Russians losing 2,000 soldiers. Regardless of this, Russian armies continued to make limited attacks on Livonian territory, which the outnumbered Swedes had less and less to oppose.

During the second major invasion of Livonia under the leadership of General Boris Sheremetyev, Russian forces defeated a 2,200 to 3,800-strong Swedish-Livonian army under Schlippenbach's command for the first time on December 30, 1701 at the Battle of Erastfer . The Swedish losses were estimated at around 1,000 men. After the victorious Russians had looted and destroyed the area, they withdrew again, as Sheremetyev attacked Charles XII. feared who was staying in Courland with a strong army . From a Swedish point of view, the unequal balance of power made a successful defense of Livonia appear increasingly unlikely, especially since the previous disdain for the Russians after their recent victory hardly seemed justified. Nevertheless, Karl refused to return to Livonia and only sent a few supplementary troops.

When Karl marched from Warsaw to Krakow in the summer campaign of 1702, thereby exposing the northern theater of war, Peter saw the opportunity again for an incursion. From Pskov an army of 30,000 men crossed the Swedish-Russian border and reached Erastfer on July 16. There, on July 19, the Russian army achieved decisive victories against the Swedes, numbering around 6,000 men, in the battle at Hummelshof (or Hummelsdorf), near Dorpat and at Marienburg in Livonia, with 840 dead and 1,000 prisoners in the battle itself, according to Swedish sources and 1,000 more suffered during the subsequent Russian persecution. The battle marked the end of the Livonian army and the starting point for the Russian conquest of Livonia. Since the remaining Swedish forces were too weak to oppose the Russians in an open field battle, Wolmar and Marienburg as well as the rural areas of Livonia fell into Russian hands in August. Extensive devastation and destruction of Livonia followed. After the looting, the Russian army withdrew to Pskov without occupying the conquered area.

Conquest of the Newaumland and Ingermanland

Since the Livonian army was de facto annihilated, Peter was able to set about creating the territorial prerequisites for his actual war goal, the establishment of a Baltic port. After the victorious campaign, Field Marshal Boris Sheremetyev led the Russian army northwards towards Lake Ladoga and Newaumland , as the Baltic Sea came closest to Russian territory there and appeared suitable for the construction of a port. This area was secured by the Swedish fortresses Nöteborg and Kexholm and a small navy on Lake Ladoga, which had hitherto prevented all Russian advances. In order to counter this threat, Peter I had a shipyard built on the southeastern beach section of Lake Ladoga near Olonetz , which subsequently built a small Russian navy. With it the Swedish ships could be pushed back to the fortress Vyborg and further actions of the Swedes on the lake could be prevented. Then the Russians turned against the fortress Nöteborg, which was on an island in the Neva at the mouth of Lake Ladoga and protected the river and the lake. At the end of September, the siege of Nöteborg by a 14,000-strong Russian army led by Field Marshal Sheremetyev began. The Swedes tried to relieve the fortress from Finland, but a 400-strong Swedish reinforcement was repulsed by the besiegers. On October 11, 1702, the Russians captured the citadel, which was last held by only 250 men. By taking Nöteborg, Peter now controlled Lake Ladoga, the Neva, the Gulf of Finland and Ingermanland. Because of the strategic importance of the fortress, the Tsar changed its name to Shlisselburg .

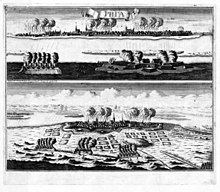

Peters' next step was the siege of Nyenschanz in March 1703 , a viable trading center and strategically important point at the mouth of the Neva in the Gulf of Finland . 20,000 Russian soldiers attacked the Swedish fortress. They began the siege and bombing of the fortress. On May 4th, Boris Sheremetyev's troops, with the help of the new Russian Navy , captured the fortress, which was occupied by 600 men. On May 18, Russia achieved its first victory at sea. Eight Russian rowing boats under the command of Peter I managed to defeat two Swedish ships in a naval battle at the mouth of the Neva .

Since the Neva was now completely controlled by Russian forces, Tsar Peter began building a fortified city in the swampy river delta in 1703, which was to become the new Russian capital in 1711 under the name of Saint Petersburg . The new city, however, needed protection. The occupation and fortification of Kotlin and, opposite in the sea, the building of Kronstadt made it impossible for the deep Swedish warships to penetrate from the sea. At the same time, the tsar had the fleet enlarged in order to be superior to the Swedes at sea. As early as the spring of 1704, Russia had a war fleet of 40 ships in the Baltic Sea.

The rest of Ingermanland including Jaama and Koporje could also be occupied by the Russians within a few weeks after the capture of Nyenschantz by a Russian infantry command under Major General Nikolai von Werdin, as the Swedes did not have any significant troops or fortresses there. In the north in particular, the Finnish fortresses Viborg (Viipuri) and Kexholm (Käkisalmi) were too close to the conquered areas. In July 1703, therefore, the first Russian attack on Finland took place, with the Viborg fortress as its target. This should be attacked on the sea side by the rowing fleet, on the land side by a siege corps under Menshikov. On the way, a Swedish-Finnish contingent opposed the Russian forces at Sestrorezk (→ Battle of Systerbäck ), which, however, had to retreat to Vyborg after eventful battles. However, for fear of a landing by Swedish forces, the siege plans were abandoned and the Russian forces were ordered back.

After the return of the Russian corps from Finland, Peter had it marched to Livonia and Estonia to support the beleaguered Polish King August II. Instead of besieging the sparsely occupied fortresses of the Swedes, the Russians contented themselves with devastating the country.

Consolidation of the Russian position in the Baltic States

Even after the Russian successes in the Neva area, Karl was not prepared to reinforce the Livonian armed forces or to intervene personally in this theater of war, although at the beginning of 1704 he had moved into winter quarters in nearby West Prussia. On his orders, all levies on the Swedish heartland had to be carried out to Poland, and in July 1704 the King of Sweden bared Livonia even further when he moved to Warsaw with 30,000 men to secure the election of his favorite as Polish king.

The fleet armored by Peter I, which was directed against Swedish merchant shipping, was also only allowed to be fought by a few frigates. To disrupt the Russians' plans for a new Baltic port, a small Swedish fleet with a ship of the line, five frigates and five brigantines sailed to the Gulf of Finland after the winter , with the order to destroy the Russian fleet and the new city in the Neva Destroying swamps. An attack on land and at sea was to be carried out with 1000 men reinforcement from Viborg. After an initially successful landing on the fortified island of Kronstadt , the venture had to be abandoned due to stubborn resistance, and the fleet sailed back.

Further battles were fought on Lake Peipus , the control of which was a prerequisite for the conquest of Livonia. At first the Swedes dominated here, who had 14 boats with 98 cannons. To counter this, the Russians built a number of boats during the winter months of 1703/04. At the beginning of May 1704, during the battle on the Embach , the Swedish fleet was completely destroyed. By controlling the lake, the Russian armed forces could now also be supplied via the inland waters for the further conquest expeditions.

As early as the summer of 1704, a Russian army under the command of Field Marshal Georg Benedikt von Ogilvy (1651–1710) was sent from Ingermanland to conquer Narva . At the same time another army advanced against Dorpat . The aim of these operations was the capture of these important border fortresses in order to protect the Ingermanland conquered in the previous year with the planned capital and to conquer Livonia . A Swedish relief attempt under Schlippenbach with 1,800 remaining soldiers failed with the loss of the entire armed force. Dorpat was included in early June, and on July 14, 1704, the city fell into Russian hands. As early as April, Narva was surrounded by 20,000 Russians in the presence of Peter I. Three weeks after Dorpat, this fortress also fell on August 9th after a violent assault and heavy fighting in the city. 1,725 Swedes were captured in the conquest of Narwas.

Unsuccessful Swedish attacks on St. Petersburg

After the successes of previous years, Russia remained on the defensive in 1705 and concentrated on securing the conquests. The Swedes, on the other hand, went on the offensive after being startled by the rapid progress in the construction of St. Petersburg. To this end, 6,000 recruits were sent to the Baltic provinces to reinforce the armed forces. A first attack by Swedish troops against the newly fortified Kronstadt in January 1705 was essentially unsuccessful. In the spring a fleet of 20 warships sailed from Karlskrona to Viborg and then to Kronstadt. The landing company failed as in the previous year, with the Swedes claiming several hundred deaths. A third attempt to land on Kronstadt failed on July 15 with the loss of 600 Swedes. Until December, the Swedish squadron crossed the Gulf of Finland and stopped trade in goods. However, there was already a disagreement among the regional Swedish commanders, who tended to go it alone, which the Russians were able to ward off without much effort.

In 1706 there was only a few fighting in the Swedish Baltic provinces. In the first half of the year, the Russian troops were deployed on the Polish theater of war to support the hard-pressed King August II and Charles XII. tie in Poland. In the north, Peter I therefore remained defensive. The Swedish forces were not strong enough for offensive ventures. In addition to a few forays into Russia, another naval advance with 14 warships to St. Petersburg was undertaken, but again remained unsuccessful. Vyborg, from where Petersburg had been attacked several times, was briefly besieged from October 11, 1706 by a 20,000-strong Russian army, which, however, was also unsuccessful. Nevertheless, in 1707 only a few main towns and fortresses in the Baltic States were still in Swedish hands, including Riga , Pernau , Arensburg and Reval . The anticipated attack by Charles on Russia, however, led to a pause in this theater of war.

The Russian victories had always been ensured by a clear numerical superiority. The tactic focused on the enemy's weak points with attacks on isolated Swedish fortresses with small garrisons. In the beginning, the Russian army avoided attacking larger fortresses. The planned use of scorched earth tactics was a hallmark of warfare on the part of the Russians. Their goal was to make the Baltic region unsuitable as a Swedish base for further operations . Numerous residents were abducted by the Russian army. Many of them ended up as serfs on the estates of high Russian officers or were sold as slaves to the Tatars or the Ottomans . The Russian army had gained self-confidence through the successful missions in the Baltic States. They proved that the tsarist army had developed effectively in a few years.

The turn of the war (1708–1709)

With the peace of Altranstädt it was Karl XII. after six long years of war, he succeeded in persuading August II to renounce the Polish throne. However, the success was marred by the fact that the Swedish Baltic provinces were now majority in Russian ownership. In addition, a Russian army had marched into western Poland in 1706 and was occupying it. During his march to Saxony, Karl had promised the concerned Western European great powers not to interfere with his army in the War of the Spanish Succession, but to turn to the East again. Tsar Peter, Charles's last opponent, should therefore be eliminated by a direct campaign on his capital Moscow. However, this turned out to be extremely unfavorable for the Swedes, as the Russian armed forces consistently used the scorched earth tactic and thus prepared the Swedish army in need of supplies. Karl tried to counter these difficulties by taking a train to the Ukraine in order to attack Moscow from the south. In 1709 he suffered a decisive defeat at Poltava , which meant the end of the Swedish army in Russia. At the news of the defeat of the Swedish king, who had been practically undefeated, Denmark and Saxony entered the war again, while Karl, cut off from his motherland, fled south to the Ottoman Empire, where he was forcibly exiled for the next few years. However, a direct invasion of Denmark in southern Sweden failed, preventing a quick Allied victory and prolonging the war.

The Russian campaign of Charles XII.

The main goals of Charles after the Peace of Altranstädt were to liberate the occupied territories in the Swedish Baltic Sea provinces and to make a lasting peace that secured Sweden's position as a great power. Therefore, in February, June and August 1707 in Altranstädt, he turned down several offers of peace by the Tsar because he considered them to be a deception and only wanted to make peace with Peter I on his own terms. In fact, Russia was ready for peace and would have been satisfied with Ingrianland . The Swedish king forced him to continue the war.

Charles XII. hoped to achieve his war aims without turning the Swedish Baltic provinces into a battlefield. For this reason, an advance on St. Petersburg was ruled out from the outset. Instead, Karl wanted to maneuver the Russian army out of Poland in order to avoid further devastation of the country, which was now allied with Sweden. From the Russian border the Swedish army was to advance directly towards Moscow, while at the same time the allied Ottomans were launching an attack on the Russian southern border.

In September 1707 the long-prepared campaign against Russia began. The main Swedish army consisted of 36,000 experienced and well-rested soldiers, newly dressed and armed with new weapons. The Swedish war chest had grown by several million thalers. The advance should be made by direct route through Smolensk . On the Russian side, it was hoped that Menshikov's army, which was still in Poland, could hold off Charles's advance long enough for Tsar Peter to organize the defense along the Russian border. However, it was not intended to hold Poland. Instead, the retreating Russian Army of Menshikov was supposed to apply the scorched earth policy , thereby depriving the advancing Swedish army of the basis of supply. On September 7, 1707 it crossed the Polish border at Steinau an der Oder . Menshikov's army avoided battle and withdrew from the western part of Poland towards the east behind the Vistula. As they retreated, Menshikov had villages along the way burned, wells poisoned and all storage facilities destroyed. At the end of October 1707, because of the mud period that began in autumn, Karl had his army held east of Posen , where new recruits increased the Swedish armed forces to a strength of 44,000 men. After the frost had made the roads passable again and the rivers frozen over, the Swedish army crossed the frozen Vistula in the last days of 1707 after a four-month break . Menshikov avoided a confrontation and withdrew further. Instead of following the trail devastated by the Russian army, the Swedes marched through the impassable Masuria , thereby bypassing the prepared defensive lines of the Russians.

The direct advance on Moscow fails

In mid-January 1708 the Swedish army left Masuria behind and reached Grodno on January 28, 1708 . Tsar Peter, who met Menshikov not far from the city, considered the strength of the Russian army to be too weak to be able to stop the Swedish army there and ordered the further retreat to the Lithuanian-Russian border. The Swedish advance lasted until the beginning of February, until the army of Charles XII. moved to winter storage near the Lithuanian town of Smorgon . During this stay, Karl met with General Lewenhaupt. The effects of the Russian tactics were already noticeable in the lack of supplies, which jeopardized the further advance. So Karl and Lewenhaupt agreed that the latter, with the 12,000-strong Livonian army and a supply train, should not join Charles's main army until the middle of the year. The supply shortages forced the Swedish army to move to Radovskoviche near Minsk in mid-March , where the supply situation was less precarious. The army stayed there for another three months to prepare for the upcoming campaign. In order to support the Polish King Stanislaus I. Leszczyński during the absence of Charles, 5,000 men were posted and sent back, so that the army was reduced to 38,000 men. The Swedish army was now divided between Grodno and Radovskoviche, while the 50,000-strong Russian army had formed itself along the line from Polotsk on the Daugava to Mogilew on the Dnieper . In addition to the protection of Moscow by Sheremetev, the Russian army also sought to counter a possible threat to St. Petersburg, which led to a greater division of forces. A suggestion made by his advisor Carl Piper to direct the advance on St. Petersburg and thus secure the Livonian provinces, Karl rejected and decided to continue the march on Moscow. After the beginning of the summer campaign on June 1st, the Swedish army crossed the Berezina on June 18th . The Russian forces were able to evade an attempt to bypass the Swedes and withdrew behind the next river barrier, the Drut . On June 30, Karl reached the Vabitch, a tributary of the Drut, near the village of Halowchyn. That was where the main line of defense of the Russian army was, and fighting broke out. In the Battle of Golovtschin on July 14, 1708, the Swedes defeated the 39,000-strong Russian army under Sheremetev, who was able to withdraw his troops in good order. The victory is classified as the Pyrrhic victory of the Swedes, as many of the 1,000 wounded died due to inadequate medical care. The battle itself was not decisive, although the Swedes were able to overcome the north-south river barriers and the way to Moscow was open.