Livonian-Estonian theater of war

| date | 1700 to 1710 |

|---|---|

| place | Swedish Livonia , Swedish Estonia |

| output | russian victory |

| consequences | Russian conquest of Livonia and Estonia |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 10,000 men (1702) | 40,000 men (1702) |

| losses | |

|

In the fighting: |

In the fighting: |

1st phase: Swedish dominance (1700–1709)

Riga I • Jungfernhof • Varja • Pühhajoggi • Narva • Pechora • Düna • Rauge • Erastfer • Hummelshof • Embach • Tartu • Narva II • Wesenberg I • Wesenberg II

Arkhangelsk • Lake Ladoga • Nöteborg • Nyenschanz • Neva • Systerbäck • Petersburg • Vyborg I • Porvoo • Neva II • Koporje II • Kolkanpää

Vilnius • Salads • Jacobstadt • Walled Courtyard • Mitau • Grodno I • Olkieniki • Nyaswisch • Klezk • Ljachavichy

Klissow • Pułtusk • Thorn • Lemberg • Warsaw • Posen • Punitz • Tillendorf • Rakowitz • Praga • Fraustadt • Kalisch

Grodno II • Golovchin • Moljatitschi • Rajowka • Lesnaja • Desna • Baturyn • Koniecpol • Weprik • Opischnja • Krasnokutsk • Sokolki • Poltava I • Poltava II

2nd phase: Sweden on the defensive (1710–1721)

Riga II • Vyborg II • Pernau • Kexholm • Reval • Hogland • Pälkäne • Storkyro • Nyslott • Hanko

Helsingborg • Køge Bay • Gulf of Bothnia • Frederikshald I • Dynekilen Fjord • Gothenburg I • Strömstad • Trondheim • Frederikshald II • Marstrand • Ösel • Gothenburg II • Södra Stäket • Grönham • Sundsvall

Elbing • Wismar I • Lübow • Stralsund I • Greifswalder Bodden I • Stade • Rügen • Gadebusch • Altona • Tönning II • Stettin • Fehmarn • Wismar II • Stralsund II • Jasmund • Peenemünde • Greifswalder Bodden II • Stresow

In the Livonian-Estonian theater of war from 1700 to 1710 in the Great Northern War , Russian troops successively conquered the Swedish provinces of Swedish Estonia and Swedish Livonia . While the Swedes were initially able to successfully repel the Allied attacks on both provinces in 1700 and 1701, in the following years the numerical inferiority compared to the Russian armed forces became increasingly noticeable. Charles XII. moved the majority of Swedish resources to the Polish theater of war and regarded the Livonian-Estonian theater of war as subordinate, although this is where most of the fighting and the highest losses of all theaters of war occurred on the Swedish side.

Troop strength

The Baltic provinces of Sweden also had to set up national militias to supplement the few existing line troops . In Estonia were four such infantry regiments set up. In Livonia the line-up was organized differently because the Swedish governor general had doubts about the reliability of the local soldiers. He raised 13 militia battalions of 300 men each. A 500-strong militia battalion was set up on the island of Ösel . This brought the total number of infantry militias in both provinces to 7,000 men. There were four dragoons squadrons dug as a militia. The total strength of these units was less than 1000 men. Despite the war, the number of militia was not increased any further. In 1700, a total of 6,600 men in eleven regiments and battalions were recruited via the Einteilungswerk , the Swedish recruiting system of the early modern period . This represented the actual army base for Livonia and Estonia.

In fact, there were never more than 10,000 men under arms on the Swedish side in Livonia and Estonia. The high losses in the battles against the overpowering Russian army could not be compensated with local and dispatched Swedish reinforcements. By the end of 1702 at the latest, the Swedes in Livonia and Estonia no longer had operational skills, but limited themselves to defending the fixed positions in Riga , Reval and Pernau on the Baltic coast. The hinterland remained completely unprotected and was regularly devastated by Russian Cossacks .

On the Russian side, as a rule, forces of 40,000 men were available for active military operations on Swedish territory. In the Russian campaigns of 1702 or 1704, superiority ratios of 4: 1 or more were achieved. The Russian forces had two large military bases in the immediate vicinity of the Swedish provinces in the Baltic States. These were Pleskau and Novgorod . Both locations had their own shipyards, Pleskau on Lake Peipus and Novgorod at the mouth of the Volkhov . Both bases were protected by defensive positions at Pechory and Gdov . Both bases regularly formed the starting point for Russian ventures and campaigns in Livonia, Estonia and Ingermanland . The latter province formed a separate theater of war with Finland .

Armed Forces Commander

| Commander of the Swedes | Commander of the Russians | Commander of the Saxons |

|---|---|---|

| Wolmar Anton von Schlippenbach | Boris Sheremetev | Otto Arnold Paykull |

| Georg Johann Maydell | Anikita Repnin | Johann Reinhold von Patkul |

| Erik Dahlberg | Christian Bauer | Jacob Heinrich von Flemming |

| Henning Rudolf Horn | Fyodor Apraxin | Adam Heinrich von Steinau |

| Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld | Avtonom Golovin | |

| Niels Stromberg | Charles de Croy | |

| Otto Vellingk | Alexanderh Imeretinsky | |

| Ivan Trubetskoy | ||

| Adam Willow |

Course of war

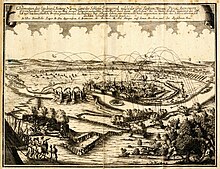

Saxon attack on Riga

On February 12, 1700, General Jacob Heinrich von Flemming, at the head of around 14,000 Saxon soldiers, invaded Livonia to take the province and its capital, Riga . The governor general of Livonia was Field Marshal Count Erik von Dahlberg , who was also Sweden's most famous fortress builder, who put his capital in an excellent state of defense. Given the strong walls of Riga, the Saxons initially took the neighboring Dünamünde one (13 to 15 Mar. 1700), that of Augustus II . was immediately renamed Augustusburg . After that, the Saxon troops set up a blockade in front of Riga, but without seriously attacking the fortress. After eight weeks, however, Dahlberg's Swedes took the initiative and defeated the Saxons in the battle at Jungfernhof (May 6, 1700). The Saxon troops evaded behind the Düna and initially waited for reinforcements. When she arrived in June 1700 under General Field Marshal Adam Heinrich von Steinau , August II personally accompanied her. Steinau went on the attack again in July, defeated a Swedish detachment under General Otto Vellingk near Jungfernhof and began the actual siege of Riga . When the siege made little progress, the Saxon side decided to secure larger parts of Livonia first. For this reason, Kokenhusen Castle was besieged in autumn and captured on October 17, 1700. Then the Saxons went to their winter quarters in Courland . The Swedish troops in Livonia were mainly recruited from Estonians , Latvians and Finns and were initially on their own. However, they benefited from the fact that the Livonian nobility did not rise up against Swedish rule. Instead, there were peasant revolts in the course of the Saxon invasion, which made the nobles all the more lean towards the Swedish crown.

Originally the Allies had agreed that Russia should open war against Sweden as soon as peace was concluded with the Ottoman Empire , if possible in April 1700. But the peace negotiations dragged on and Peter I hesitated, despite the urging of August II to join the war. An understanding with the Ottomans was only achieved in mid-August 1700, and on August 19 Peter I finally declared war on Sweden. However, he did so in complete ignorance of the fact that an important ally of the coalition, Denmark, had already ceased to exist the day before . In a report on September 3 , the Dutch envoy therefore stated: “If this news had arrived a fortnight earlier, I very much doubt whether S. Czarian Majesty would march with her army or S. Majesty the King of Sweden Would have declared war. "

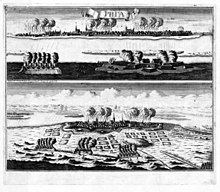

Russian siege of Narva

from: Johann Christoph Brotze : Collection of various Liefland monuments

However, as early as the summer of 1700, Peter I had an army set up on the Swedish borders, which largely consisted of young recruits who had been trained on the Western European model. Overall, the armed forces were divided into three divisions under Generals Golowin , Weide and Repnin . Another 10,500 Cossacks joined them , so that the total armed forces amounted to about 64,000 men. However, a large part of these still stood inland. A Russian vanguard entered Swedish territory in mid-September, and on October 4, 1700, the main Russian army began the siege of Narva with around 35,000 soldiers . Before the war, Peter I had claimed Ingermanland and Karelia for himself in order to get safe access to the Baltic Sea. Narva was only 35 kilometers from the Russian borders, but in Livonia, which was claimed by August II. The allies therefore mistrusted the tsar, and they feared that he wanted to conquer Livonia for himself. However, there were three reasons in favor of Narva as the target of the Russian attack: It was south of Ingermanland and could serve as a gateway for the Swedes into this province. It was not far from the Russian borders and was therefore a relatively easy logistically accessible destination. Last but not least, it was important that almost all of Russia's trade to the west ran via Riga and Narva and that the Tsar would not have liked to see both cities in the possession of August II.

Relief from Narva and Riga by the Swedish army

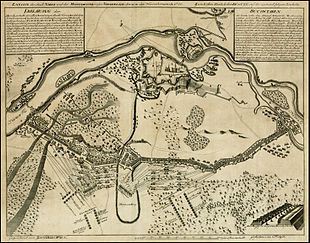

Fortifications, troop movements, batteries of the Battle of Narva drawn by Zacharias Wolf .

Meanwhile, Charles XII. his army withdrew from Denmark by August 24, 1700. Since then, he has been preparing an expedition to Livonia in southern Sweden to face the Saxon troops there. Despite the impending autumn storms, Karl left Karlskrona on October 1st and reached Pärnu on October 6th . The Swedish associations suffered losses from violent storms. Nevertheless, the fleet was immediately sent back to transfer more soldiers and the heavy artillery . Since he found the old Dahlberg victorious in Riga and the Saxons were already in their winter quarters, he decided to turn against the Russian army at Narva. He moved his troops to Reval , where he gathered further reinforcements from the region and had his units drilled for several weeks. On November 13, 1700, he set out east with around 10,500 soldiers. The march in cold weather and almost without any supplies proved difficult, but on November 19th the Swedes reached the Russian positions. On the following day, the battle of Narva (November 30th, 1700) took place, in which the Swedish troops defeated the outnumbered Russian army. In the course of the fighting and the subsequent escape, the Russian army almost completely disintegrated and practically lost all of its artillery. However, the few Swedish forces were also weakened, and after Narva was liberated, they too had to move into their winter quarters first.

After the usual army shows began on June 17, 1701 the Swedish advance via Wolmar and Wenden to Riga. Karl planned to move his army across the Daugava between Kokenhusen and Riga. The Saxons had suspected this approach and built field fortifications at several transitional positions along the Düna. Both armies met for the first time on July 8th . / July 19, Greg. near Riga on the Daugava river. The Saxon-Russian army with 25,000 men was slightly superior to the army of around 20,000 Swedes. This advantage was lost, however, as the Saxon commander-in-chief Adam Heinrich von Steinau allowed himself to be deceived by Swedish diversionary maneuvers and split his units along the Daugava. So the Swedish infantry managed to cross the raging river and to form a bridgehead on the river bank held by the Saxons. The Saxon army suffered a defeat in the ensuing battle on the Daugava , but was able to rally and withdraw in an orderly manner, except for Prussian territory. The Russian troops also withdrew to Russia, shocked by the renewed defeat.

Russian war plans after the battle of Narva

Charles XII. After the victory in the Battle of Narva at the end of November 1700, his main army had moved south to fight August II. He transferred the supreme command of the Swedish Baltic Sea holdings to Major General Abraham Kronhjort in Finland , Colonel Wolmar Anton von Schlippenbach in Livonia and Major General Karl Magnus Stuart in Riga. The Swedish warships in Lake Ladoga and Lake Peipus were commanded by Admiral Gideon von Numers . At that time the Russian army was no longer a serious enemy. Because of the resulting certainty of victory, Karl rejected Russian peace offers. The tactical superiority of the Swedes over the Russians had solidified as a prejudice also in the thinking of Karl, who was so convinced of the minor importance of Russian clout that he concentrated his war efforts on the Polish theater of war even then, as a large part of Livonia and Ingermanland was under Russian control.

By shifting the main Swedish power to the Polish theater of war, however, the chances of Peter I to lead the war to a more favorable course and to conquer the desired access to the Baltic Sea for Russia increased. Tsar Peter took advantage of the withdrawal of the Swedish army and let the remaining Russian forces resume their activities in the Swedish Baltic provinces after the disaster in Narva. The war strategy of the Russians was based on exhaustion of the enemy. This should be achieved through forays and constant attacks, combined with the starvation of the population through the destruction of the villages and fields. At the same time, the Russian soldiers were supposed to get used to the Swedish war tactics with their violent attacks in battle through the constant fight.

Tsar Peter used the time saved by the absence of the Swedish army to rearm and reorganize his army with enormous efforts. So he called foreign experts to train the troops - equipped with modern weapons - in the methods of Western European warfare. In order to quickly rebuild the artillery that was lost at Narva, he had church bells confiscated so that cannons could be poured from them. He had hundreds of gunboats built on Lake Ladoga and Lake Peipus . As early as the spring of 1701, the Russian army again had 243 cannons, 13 howitzers and 12 mortars . Reinforced by new recruits , it again consisted of 200,000 soldiers in 1705 after the 34,000 remaining in 1700.

In order to diplomatically support his war plans, the tsar had a negotiator sent to Copenhagen in parallel to the statements of support to August II to persuade Denmark to invade Skåne . When the Swedish Imperial Council had a force advance to the Sound , the alliance plans failed and the Danes postponed their attack.

The Swedish forces in the Baltic States under Colonel von Schlippenbach were only very weak and also separated into three autonomous corps . Each of these corps was too weak in itself to be able to counter the Russian forces successfully, especially since they were not led in a coordinated manner. In addition, these troops were not composed of the main regiments but of newly recruited recruits. Swedish reinforcements were primarily sent to the Polish theater of war, so that one strategically important point after another could be conquered by the Russian army.

Defeat of the Livonian army

In mid-1701, first Swedish and then Russian forces carried out forays into Ingermanland and Livonia and marched into the respective opposing territory, where they fought several skirmishes . The Russian forces had recovered enough to be able to make limited offensives. From the Russian headquarters at Pskov and Novgorod , a force of about 26,000 men moved south of Lake Peipus to Livonia in September . In the subsequent campaign, the Swedish General Schlippenbach succeeded in September 1701 with a detachment of only 2,000 men to defeat the 7,000-strong Russian main army under Boris Sheremetyev in two meetings at Rauge and Kasaritz , with the Russians losing 2,000 soldiers. Regardless of this, Russian armies continued to make limited attacks on Livonian territory, which the outnumbered Swedes had less and less to oppose.

During the second major invasion of Livonia under the leadership of General Boris Sheremetyev, Russian forces defeated a 2,200 to 3,800-strong Swedish-Livonian army under Schlippenbach's command on December 30, 1701 in the Battle of Erastfer . The Swedish losses were estimated at around 1,000 men. After the victorious Russians had plundered and destroyed the area, they withdrew again, as Sheremetyev attacked Charles XII. feared who was staying in Courland with a strong army . From a Swedish point of view, the unequal balance of power made a successful defense of Livonia appear increasingly unlikely, especially since the previous disdain for the Russians after their recent victory hardly seemed justified. However, Karl refused to return to Livonia and only sent a few supplementary troops.

When Karl marched from Warsaw to Krakow in the summer campaign of 1702, thereby exposing the northern theater of war, Peter saw the opportunity for an incursion again. From Pskov an army of 30,000 men crossed the Swedish-Russian border and reached Erastfer on July 16. There, on July 19, the Russian army achieved decisive victories against the Swedes, who numbered around 6,000 men, in the battle at Hummelshof (or Hummelsdorf), near Dorpat and at Marienburg in Livonia, with 840 own deaths and 1,000 prisoners in the battle itself, according to Swedish information and 1,000 more suffered during the subsequent persecution by the Russians. The battle marked the end of the Livonian army and the starting point for the Russian conquest of Livonia. Since the remaining Swedish forces were too weak to oppose the Russians in an open field battle, Wolmar and Marienburg as well as the rural areas of Livonia fell into Russian hands in August. Extensive devastation and destruction of Livonia followed. After the looting, the Russian army withdrew to Pskov without occupying the conquered area.

Consolidation of the Russian position in the Baltic States

Even after the Russian successes in the Neva area, Karl was not prepared to reinforce the Livonian armed forces or to intervene personally in this theater of war, even though he had taken winter quarters in nearby West Prussia at the beginning of 1704. On his orders, all levies in the Swedish heartland had to be carried out to Poland, and in July 1704 the King of Sweden exposed Livonia even further when he moved to Warsaw with 30,000 men to secure the election of his favorite as Polish king.

Further battles were fought on Lake Peipus , the control of which was a prerequisite for the conquest of Livonia. At first the Swedes dominated here, with 14 boats with 98 cannons. To counter this, the Russians built a number of boats during the winter months of 1703/04. At the beginning of May 1704 the Swedish fleet was completely destroyed . By controlling the lake, the Russian armed forces could now also be supplied via the inland waters for further conquest campaigns.

As early as the summer of 1704, a Russian army under the command of Field Marshal Ogilvy (1651–1710) was sent from Ingermanland to conquer Narva . At the same time another army advanced against Dorpat . The aim of these operations was the capture of these important border fortresses in order to protect the Ingermanland conquered last year with the planned capital and to conquer Livonia . A Swedish relief attempt under Schlippenbach with 1,800 remaining soldiers failed with the loss of the entire armed force. Dorpat was included in early June, and on July 14, 1704, the city fell into Russian hands. In April Narva had been surrounded by 20,000 Russians in the presence of Peter I. Three weeks after Dorpat, this fortress also fell on August 9th after a violent assault and heavy fighting in the city. 1,725 Swedes were captured in the conquest of Narwas.

Nevertheless, in 1707 only a few main towns and fortresses in the Baltic States were still in Swedish hands, including Riga , Pernau , Arensburg and Reval . The anticipated attack by Charles on Russia, however, led to a break in this theater of war. The Russian victories had always been ensured by a clear numerical superiority. The tactic focused on the opponent's weak points with attacks on isolated Swedish fortresses with small garrisons. In the beginning the Russian army avoided attacking larger fortresses. The planned application of scorched earth tactics was a hallmark of warfare on the part of the Russians. Their aim was to make the Baltic region unsuitable as a Swedish base for further operations . Numerous residents were abducted by the Russian army. Many of them ended up as serfs on the estates of high Russian officers or were sold as slaves to the Tatars or the Ottomans . The Russian army had gained self-confidence through the successful missions in the Baltic States. They proved that the tsarist army had developed effectively in a few years.

While Charles XII. negotiated with the Sultan about the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war, Tsar Peter completed the conquest of Livonia and Estonia. The Russians conquered Vyborg in June 1710 , on July 4, 1710, after a long siege by Field Marshal Sheremetyev's troops , Riga surrendered . On August 14, 1710, after a brief siege, Pernau capitulated . After the capitulation of Arensburg and the capture of the island of Ösel by the Russians, Reval (today's Estonian capital Tallinn) was the last fortress that Sweden claimed in Livonia. After the Russian campaign through Livonia in the late summer of 1704, the fortifications were extensively renewed and expanded, and the garrison was also increased to almost 4,000 men. The siege of the city by Russian troops began in mid-August 1710. At the beginning of August the plague broke out, the spread of which was accelerated by the influx of refugees and the resulting overpopulation. The situation worsened to such an extent that the Swedish leadership finally signed the surrender on September 29 and left the city to the Russian commander Apraxin .

consequences

In 1721 Sweden was forced to peace. The war also decided the fate of Estonia and Livonia. Of around 350,000 inhabitants of Livonia and Estonia before the outbreak of war, only around 120,000 were alive in 1721. The devastation of the country by the Russians, the fighting as well as the deportation of the civilian population into slavery in Russia as well as the plague and famine led to massive population losses that could only be compensated for after decades. Livonia, which from then on belonged to Russia, was able to maintain its internal autonomy for some time. In the Peace of Nystädter in 1721, Emperor Peter endowed the estates with privileges binding under international law, which were confirmed by all subsequent empresses up to Alexander II (1855). The privileges include: freedom of belief, German administration, German language, German law. Estonia, Livonia and Courland (from 1795) are therefore also referred to as the "German" Baltic provinces of Russia.

Overview map

| ||

Battle of the theater of war

| battle | date | Swedish forces | Allied forces | Swedish losses | Allied losses | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle at Jungfernhof | June 5, 1700 | 3200 | 1500 | k. A. | k. A. | Swedish victory |

| Siege of Riga | February 12, 1700 - October 1700 | 4000 | 18,000 | k. A. | k. A. | Swedish victory |

| Battle at Varya | November 7, 1700 | 800 | 5000 | 280 killed and wounded | 1500 killed, wounded and captured | Swedish victory |

| Battle of Narva | November 30, 1704 | 12,300 | 37,000 | 667 killed, 1247 wounded | 9,000 killed, 20,000 prisoners | Swedish victory |

| Battle at Pechora | February 23, 1701 | 4100 | 6000 | 30 killed, 60 wounded | 500 killed | Swedish victory |

| Battle of the Daugava | July 19, 1701 | 14,000 | 29,000 | 100 killed, 400 wounded | 1300 killed and wounded, 700 prisoners | Swedish victory |

| Skirmishes at Rauge | September 15, 1701 | 2000 | 7000 | 100 killed and wounded | 2000 killed, wounded and prisoners | Swedish victory |

| Battle of Erastfer | January 9, 1702 | 3470 | 18,087 | 700 killed, 350 prisoners | 1000 killed, 2000 wounded | Russian victory |

| Battle at Hummelshof | July 29, 1702 | 6000 | 23,969 | 840 killed, 2000 prisoners | 1500 killed and wounded | Russian victory |

| Battle of the Embach | May 7, 1704 | 570 | 7317 | 190 killed, 142 prisoners | 58 killed, 162 wounded | Russian victory |

| Siege of Tartu | June 4th-13th July 1704 | 5000 | 21,000 | 810 killed and wounded | 317 killed, 400 wounded | Russian victory |

| Siege of Narva | June 27 to August 9, 1704 | 4500 | 45,000 | 2,700 killed, 1,800 prisoners | 359 killed, 1,340 wounded | Russian victory |

| Battle of Wesenberg | June 26, 1704 | 1400 | 8000 | 400 killed, 600 prisoners | k. A. | Russian victory |

| Battle at Wesenberg | August 16, 1708 | 1500 | 3300 | 704 killed, 244 prisoners | 16 killed, 53 wounded | Russian victory |

| Siege of Riga | November 14, 1709 - July 4, 1710 | 13,400 | 40,000 | 8,000 killed | 9800 killed | Russian victory |

| Siege of Pernau | August 16, 1708 | 1000 | 6000 | 880 killed | k. A. | Russian victory |

| Siege of Reval | August 18 - September 30, 1710 | 4000 | 15,000 | 1420 killed | k. A. | Russian victory |

literature

- Not so Fryxell: Life story of Charles the Twelfth, King of Sweden. Freely adapted from the Swedish original by Georg Friedrich von Jenssen-Tusch, 5 vols., Vieweg, Braunschweig 1861, volume 1

- Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. 2010.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 268.

- ↑ Heinz von Zur Mühlen: Baltic historical local dictionary. Volume 2, Cologne 1990, p. 132.

- ↑ Knut Lundblad: History of Karl the Twelfth, King of Sweden. Translated from the Swedish original, corrected and expanded by Georg Friedrich von Jenssen-Tusch, Volume 1, Hamburg 1835, pp. 41–55 .

- ^ Georg Piltz: August the Strong - dreams and deeds of a German prince. Berlin (East) 1986, p. 92 f.

- ↑ Quoted from: Georg Piltz: August the Strong - Dreams and Deeds of a German Prince. Berlin (East) 1986, p. 92 f.

- ^ Henry Vallotton: Peter the Great - Russia's Rise to a Great Power. Munich 1996, p. 165.

- ↑ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, p. 288 f.

- ↑ In detail to the Narva campaign: Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great - His life and his time. Frankfurt / Main 1987, pp. 290-301.

- ↑ Anders Fryxell: Life story of Charles the Twelfth, King of Sweden. Freely adapted from the Swedish original by Georg Friedrich von Jenssen-Tusch, 5 vol., Vieweg, Braunschweig 1861, volume 1, p. 118 .

- ↑ a b Christopher Duffy: Russia's Military Way to the West. Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power, 1700--1800. London 1981, p. 17.

- ↑ In 1701 they consisted of around 3,100 field troops, a 2,000-man garrison in Dorpat , 150 men in Marienburg, six smaller warships with 300 men and land militia. Figures according to information from WA v. Schlippenbach.

- ^ Peter Englund: The Battle that Shook Europe. Poltava and the Birth of the Russian Empire. Pearson Education Verlag, New York 2003, p. 39.

- ^ William Young: International Politics and Warfare in the Age of Louis XIV and Peter the Great. A Guide to the Historical Literature. Lincoln 2004, Chapter 8: The Struggle for Supremacy in the North and the Turkish Threat in Eastern Europe, 1648–1721, pp. 414–516, here: p. 452 .

- ^ According to the official Russian report of the battle, 5,000 Swedes are said to have been killed, with their own losses of 400 men. Rossiter Johnson: The Great Events by Famous Historians , p. 324.

- ^ Peter Englund: The Battle that Shook Europe. Poltava and the Birth of the Russian Empire. Pearson Education Verlag, New York 2003, p. 40.