Saxon Army

The Saxon Army was the army of the Electorate and later Kingdom of Saxony and existed as a standing army since 1682. In the Electorate of Saxony, the army was called the Electoral Saxon Army . With the rise of Saxony to a kingdom by Napoleon in 1807, the name of the army was changed to the Royal Saxon Army .

The army formed the Saxon contingent in the contingent armies of the German Confederation and the North German Confederation and, in accordance with Article 63 (1) of the Imperial Constitution of April 16, 1871 , still remained legally independent in the German Empire . As a result of Germany's defeat in World War I and the end of the monarchy in Saxony, the country lost its limited military autonomy and the Saxon army went 1919 Reichsheer the Weimar Republic on.

history

Vassal armies and mercenary armies

The first dukes and electors of Saxony had only one personal bodyguard. In the event of a campaign, a small band of knights was set up to protect the ruler. A real army was only set up when an invasion of one's own territory threatened, to support another ruler in a campaign or in feuds . The duke provided the knights on horseback with weapons, equipment and maintenance. The citizens and farmers of the country served their liege lords as infantry. When peace returned to the principality, the army was dissolved again.

Despite the lack of training, these vassal armies won victories for their princes. Margrave of Meissen Friedrich III. the severity fought successfully against Count Heinrich VIII von Henneberg-Schleusingen . The Margrave married his daughter Katharina von Henneberg after the end of the hostilities in order to bind the Henneberg family closer to himself. Frederick I the Arguable won with his armies victories over the Swabians and Rhinelander as well as over the army of Philip of Nassau. He also achieved an important victory in the battle of Brüx in 1421 in the war against the Hussites. In 1426 the Saxon army lost against the Hussites in the battle of Aussig . 500 knightly followers and twelve counts died in this battle . There is no information about the casualties of the infantry. His son Friedrich II. The Meek fought against the Counts of Orlamünde and von Schwarzburg as well as the Lords of Treffart and other opponents.

As the first Duke of Saxony, Albrecht the Brave used the mercenary army . Albrecht thought economically, because his liege lords and their subordinates were more useful to him if they pursued their traditional tasks in their home country and the duchy continued to be managed at the same level. Like the vassal armies, the mercenary armies were retired from service after the end of the campaign, and only the bodyguard and a few foot soldiers who guarded the cities and castles remained in the service of the duke. Until the Duke and later Elector Moritz , the mercenary armies were regularly recruited. The Duke Moritz was the first to recognize the value of a permanent army to protect the country. During his reign, parts of the mercenary army were used to occupy the larger cities such as Dresden , Leipzig and Pirna , which Moritz had fortified. In addition, mercenaries were also used as permanent occupying forces of fortresses and stately palaces.

The Duke also began to introduce a military ordinance for all troops fighting under his banner. This laid down the first rules and regulations for handling weapons and equipment. The introduction of firearms also meant that from now on the army departments were divided into regiments and companies . The legions and centurions of the Roman army of antiquity served as a template . Likewise, the infantry was now divided into ensigns and the cavalry into squadrons. This subdivision enabled better command of the troops on the battlefield. These changes made it possible in the middle of the 16th century to effectively command large armies of up to 100,000 men and use them in a war.

A major disadvantage of the mercenary army was the weaning of the nobility from national defense. This no longer saw it as necessary to defend property with oneself. He trusted in his sovereign. In addition, the mercenary armies were sometimes difficult to control. The commanders were responsible for the maintenance of the mercenaries themselves. As a result, if a sovereign did not pay any wages, the mercenaries plundered the land they actually had to protect. After mercenary armies became a common practice in the 16th century, these troops became increasingly expensive to maintain. A real mercenary trade developed. The armies fought for the side that paid better. It could happen to a sovereign who was in serious financial distress that parts of his mercenary armies were withdrawn from the army association and passed over to the enemy because the latter paid the mercenaries better. This was one of the reasons why, at the beginning of the 17th century, compulsory military service for the people was reintroduced in several Central German states .

Defensionswerk, Faith and Cabinet Wars (1612–1682)

During the uncertain reign of Elector Johann Georg I (1611–1656), far-reaching reforms were carried out in the Saxon military system. In 1612 the state parliament approved the proposal for a defense army . These were the first attempts to maintain standing troops, which were formed without the consent of the emperor. The Imperial Execution Order of 1555 formed the legal basis for this. In the following years two regiments of foot servants, each with eight companies (520 men each), and two regiments of knight horses of 930 and 690 men were recruited. In addition there was cavalry with 1593 knight horses in two regiments and with 16 senior officers. Finally there were 1,500 entrenchment workers and 504 servants for the military vehicles and guns. Thus the Saxon Defensionwerk, which was recruited from resident men according to districts and offices, had a total strength of almost 14,000 men. That was the size of a medium army at the time. This had the task of protecting the national borders from attacks from outside and defending fixed places, hence the name Defensioner (Latin for defender). After 1619, the Defensioners were repeatedly used to occupy the border passes on the Ore Mountains ridge to Bohemia. Three companies of foot servants, the Alt-Dresdner Fähnlein, the Pirnaische and the Freiberg Fähnlein, with 304 men were quartered around Dresden for the special protection of the state capital. However, the military power of the Defensionwerk was not able to adequately protect the country's borders, and the military value of this force was severely limited. After 1631, Saxon cities besieged by Swedes or imperial troops could easily be captured. Only Freiberg was an exception twice.

At the beginning of the Thirty Years' War , Kursachsen prepared a 12,000-strong attack army under the command of Count Wolfgang von Mansfeld in the name of the emperor and fought against the troops of the Bohemian estates in the Bohemian-Palatinate period, starting with the campaign in Upper and Lower Lusatia 1620. The most important event was the siege of Bautzen . After taking possession of the two Lausitzes, the gradually strengthening Saxon army marched into Silesia, which also belonged to the Bohemian Crown, and fought here until the Saxon troops were replaced by imperial troops in 1622. After that, troops were recruited in 1623, but the general war situation allowed almost all Saxon troops to be abdicated by 1624. In the second, the Danish period of the war, the Saxons did not take part in combat operations. The country was only touched or briefly crossed by those involved. After the brutal conquest of the city of Magdeburg ( Magdeburgization ), the Saxon sovereign changed sides and fought from then on in the Protestant camp against the Catholic League . For the fight on the side of Sweden, in the spring of 1631 the elector raised a new army of over 52,000 men with completely new regiments on horseback, on foot and dragoons. As in most Protestant countries, the formation and fighting style of the new Electoral Saxon units were the so-called Dutch orderly . This was largely retained, and the other, especially Catholic armies adapted. The main types of soldiers in the infantry were the musketeers and pikemen , in the cavalry the cuirassiers and arquebusiers .

| Branch of service | Companies | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Cuirassiers | 169 | 19,756 |

| dragoon | 16 | 1,808 |

| infantry | 136 | 30,416 |

| artillery | 2 | 250 |

| Overall strength | 323 | 52,229 |

The cuirassiers only appeared at the beginning of the Swedish period because of the style of fighting, but above all the higher costs. The mounted infantry were the dragoons . The Saxons did not have easy riders like the imperial ones. In addition to these types, there were artillery servants, trench diggers, bridge and ship servants, as well as military craftsmen. The supreme command of this newly formed Saxon lord was given to Field Marshal Hans Georg von Arnim-Boitzenburg . The Electoral Saxon army received its first baptism of fire in the first battle near Breitenfeld in 1631. In 1633 the Electoral Saxon army conquered Upper Lusatia and took the fortress of Bautzen after a two-day siege. Subsequently, the army marched into Silesia and inflicted a crushing defeat on an imperial army under the command of Colloredo in the Battle of Liegnitz . The troops of the Catholic League had 4,000 dead and wounded. This defeat forced the German Kaiser to negotiate peace with Saxony.

The concluded peace treaty made the Swedes an enemy of the Saxons again. These then began with attacks on the electorate. In the second battle of Breitenfeld in 1642, the imperial Saxon army was defeated and the electorate was occupied by the Swedes. The hostilities between Sweden and Saxony were not settled until the armistice of Kötzschenbroda in 1645. Saxony was one of the winners of the Thirty Years' War in terms of territorial gains. In the Reichstag, Saxony was awarded the chairmanship of the Corpus Evangelicorum , so from then on it was the leading Protestant power in the empire. From 1648 the territorial lords were allowed to direct a standing army in independent organization without restriction. After the last Swedish occupation troops left Saxony in 1650, Johann Georg reduced his army. In 1651 the Saxon field army was disbanded. Only 121 horsemen, 143 artillery men and 1,452 infantrymen remained in the service of the elector.

After the death of Johann Georg I in 1656, his son Johann Georg II (1656–1680) took office as elector. This was considered a monarch who loved splendor. Several guard formations supported the splendor and splendor of the elector's lavish court life. In 1660 the bodyguard was increased by a company of Croatian horsemen and a Swiss guard on foot was founded. Under him the Saxon army experienced a slight increase. The Defension Recess of October 25, 1663 marked a first step on the way from the Defensionwerk to the standing army. A corps consisting of 3,000 men, which was divided into six pennants and kept in constant readiness, took the place of the defensioners. The cost was shared by the elector and the estates. Johann Georg also set up several regiments that supported the imperial army on the Rhine in the war against France in 1673. Johann Georg II recognized that an increase in artillery troops was necessary to defend the country. The elector therefore used the time of inner peace to expand his artillery. The reinforcement of fortifications and the defenses of the big cities as well as an increase in the number of guns and troop strength of the artillery bore his signature.

Establishment of the standing army (1682–1699)

The elector Johann Georg III is considered to be the founder of the standing army in Saxony . , also known as the “Saxon Mars” (1680–1691). He had embarked on a military career in the Saxon body regiment on foot. With this regiment he took part in the Turkish campaign in Hungary. In the Battle of Lewanz on July 9, 1664, he stood out as the commander. In the Imperial War against France 1676–1678, he led the Saxon contingent. He was also the commanding officer of the Prince Elector Johann Georg cavalry regiment . After the death of his father in 1680 he was elector of Saxony. He restricted his father's lavish court and instead wanted to assist the militarily oppressed emperor in the fight against the Ottomans. The elector wanted to take up the political and national competition with the Brandenburg electoral state and outstrip it in the hierarchy of the empire.

The instrument of power required for this was created under his leadership as the first standing Saxon army. He convinced the Saxon estates in 1681 that the previous practice of setting up mercenary armies in the event of war and dismissing them in peace was more expensive than forming a standing army. He was able to rely on the Reich Defense Order passed by the Reichstag in 1681 with the aim of reorganizing the Reich constitution in view of the threats from the East and the West. First, in 1682, the body and guard troops and other smaller troops that had existed up to that point were restructured into line regiments . The army at that time consisted of six infantry regiments of eight companies each and five cavalry regiments, a total of 10,000 men. The field artillery had a strength of 24 guns. By creating the standing army, together with Kurbrandenburg and Kurbayern, he modernized the country's military strength.

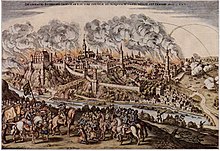

On June 4, 1683, Johann Georg III. into an alliance with Emperor Leopold I with the aim of defending the empire. Shortly afterwards from July 1683 the Ottomans besieged Vienna . The Saxon elector sent a contingent of 11,000 men as relief. In addition to the Poles, the Saxon troops particularly distinguished themselves in storming the Ottoman camp. Johann Georg III. adopted the same dissolute lifestyle as his father. In order to be able to finance this, he rented his soldiers as a mercenary army. In 1686 he again supported Emperor Leopold's Turkish War . On payment of subsidies of 300,000 thalers , he sent a 5,000-strong auxiliary corps to Hungary. Two cavalry and three infantry regiments successfully took part in the storming of Ofen on September 2, 1686 . On September 6, 1688, the 1500-strong “Kurprinz Regiment” took part in the conquest of Belgrade . As early as 1685 he had rented 3,000 Saxon regional children to the Republic of Venice for their war in Morea ( Peloponnese ) for 120,000 thalers for two years, of which only half came back two years later. Furthermore, in 1688 he left up to 10,000 men ( soldier trade ) to the Dutch States General . In the same year Louis XIV broke the armistice agreed with the Reich and marched into the Rhine plain . Johann Georg III. moved to Franconia with his army of 14,000 men in October 1688 . After the declaration of the Imperial War against France on April 3, 1689, the Electoral Saxon army took part in the siege and capture of Mainz on September 11, 1689 with great losses . In 1690 and 1691 the Saxon army was part of the Imperial Army, whose supreme command was Johann Georg III. was transferred in March, on the Rhine. This third campaign was completely unsuccessful, especially since epidemics broke out in the army. During this campaign, the elector died on September 12, 1691 in a field camp near Tübingen .

His son Johann Georg IV (1692–1694), who was in the field with him , was appointed elector and took the oath of allegiance from his army while still in the camp. The new elector strongly advocated the further expansion of the standing army. He was also not afraid to threaten the use of military force if the estates did not provide the funds required for the expansion of the army. Ultimately, both parties agreed to finance an army of 12,000 men. A well-trained officer corps was crucial for the effective command and control of the military formations. To this end, the elector had the cadet school set up in Dresden-Neustadt in 1692 , at which 165 cadets began officer training. The elector also created the “Grands-Mousquetaires” guard regiment. Johann Georg IV could not bring about any further changes in the army, because he only ruled for three years and allegedly died in 1694 of the Blattern . According to new scientific findings, however, it is assumed that he was poisoned by his younger brother Friedrich August I. This followed him to the royal throne. Under the Elector Friedrich August I (1694–1733), also known as August the Strong, a new period of prosperity began for the Saxon army. Friedrich August had previously received sufficient military training. As a youth he took part in his father's campaigns in the association of the Reichsheeres on the Upper Rhine from 1689 to 1691.

Military defeats in the Great Northern War (1700–1716)

Around 1700, Saxony was considered to be a more powerful state structure on a European scale due to its closed territory. In the empire itself, the imperial princes sought political sovereignty from the established dominance of the Habsburg dynasty. In particular, the Brandenburg, Bavarian and Hanoverian princes (England) endeavored to acquire a royal crown located outside the empire in order to avoid the threat of a loss of rank and power. In addition to Brandenburg, whose elector crowned himself king in Prussia in 1701 , and Hanover, only August of Saxony succeeded in doing this, who died on 26/27. June 1697 on the electoral field in Wola was elected king in Poland against all initial expectations. From then on, Saxony, which was now part of the personal union of Saxony-Poland, was involved in a variety of political and military conflicts, which the Saxon army in particular could not sustain in the long term and which by far exceeded the powers of the electorate. Friedrich August I felt himself to be the newly elected King of Poland from the Swedish King Karl XII. threatened. Too few regiments were available to defend Poland, and the German Emperor's Turkish War in Hungary meant that 12,000 of his best soldiers were held in southern Europe until 1699. He began recruiting new troops and establishing new regiments. Many of these regiments were stationed in northern Poland in order to counter a possible attack by the Swedes as quickly as possible.

The elector did not want to wait for an attack by the Swedish king. In the spring of 1700 he attacked Swedish Livonia . When he was elected King of Poland, he had promised to tie the former Polish province back to the crown. He already had 41 squadrons of cavalry and 24 battalions of infantry in the field and also tried to bring the Polish regiments under his command. The Polish army was not subordinate to the king, but to the Reichstag, and the king had to ask for military support in the fight against the Swedes. By quickly conquering Livonia, August II hoped to gain command of this army in order to lead it to war against Sweden. The campaign in Livonia marked the beginning of the Great Northern War . Initially, under the command of Field Marshal Jacob Heinrich von Flemming, the fortress of Dünamünde and the Koberschanze were conquered by the Saxon army. The fortress of Riga was besieged twice in 1700 due to a lack of guns and ammunition . The landing of the Swedish troops under the supreme command of King Charles XII. forced the Saxon army after the renewed defeat of the Saxons in the battle of the Daugava to retreat to Polish territory.

Due to the ineffectiveness and unsuccessful leadership of his troops in this campaign, the King of Poland was forced to enlarge and restructure his army. The existing line infantry regiments were to be increased from 10 to 24 in the course of 1701. From then on, each regiment had to be strong with 13 companies. In addition, each regiment received a grenadier company from now on . The manpower of each company was increased from 72 to 120 soldiers. The king also had all infantry regiments equipped with new flintlock rifles in order to increase the firepower of the line infantry. In the spring of 1702, after the urgent restructuring, an army of 27,000 men was again ready to fight the King of Sweden. This had marched into Poland and threatened the capital Warsaw. Charles XII. wanted to drive the Saxon king from the Polish throne and replace him with Stanislaus I. Leszczyński, who was loyal to Sweden . But notwithstanding the improvements that had already been made, the Saxon army suffered another defeat in the Battle of Klissow , which was considered a decisive battle for the Polish crown. Although the Saxon army was close to victory, it was given lightly from their hands. The Saxon-Polish army had 2,000 dead and wounded. In addition, 1,700 men were taken prisoner in Sweden. With this, the Saxons lost control of Poland to the victorious Swedes, who subsequently defeated the Saxons again and again until 1706 and were able to conclude a victory peace with the Peace of Altranstädt in 1706 . The participation of Saxon troops in the War of the Spanish Succession from 1702 to 1704 and from 1705 to 1712 also had an adverse effect during this time .

As a result of the negative war experience with the Swedish army, which was considered the best in Europe at the time, restructuring and innovations were made. In the years 1704 and 1705, the drill regulations were revised by the generals von Schulenberg and von Flemming and issued specifically for the infantry and cavalry. In the years that followed, these regulations were continuously improved and were concluded in 1729 with the introduction of new regulations, which were applied theoretically and practically in the regiments in the so-called drill camp. In 1706 the Secret Cabinet was founded under the direction of Oberhofmarschall Pflugk. The cabinet included the ministerial posts for internal and external affairs as well as for military affairs. With this step, the influence of the Saxon estates on military and political decisions was severely restricted. The ministers were appointed directly by the elector. This cabinet actually only served to further develop the absolutism that August the Strong wanted to enforce in Saxony. Count Flemming was appointed the first Minister for Military Affairs. With the help of this institution, the Saxon elector was able to enlarge his army at will and provide it with financial means without asking the Saxon state parliament. This cabinet was the basis for the massive expansion of the Saxon army both during the Northern War and afterwards.

At the time of the Northern War, the regiments mostly did not have the total strength that the elector demanded and with which he reckoned in the battles. August II reserved the right to decide on all promotions himself. He kept index cards on all command officers with precise descriptions of leadership and lifestyle. The pensions of the officers were also personally recorded by the elector. According to the Saxon tradition, August II reinforced his standing army in the Northern War with land militias. These were mainly responsible for defending the national borders. The militias consisted of Saxon citizens who were drafted twice a year for combat service and weapons training. These militias were important reserves in the restructuring of 1709 and 1716. They were dissolved in 1717 and restructured into four district regiments to a total of 2,000 men.

Reorganization and reinforcement of the army in peacetime (1717–1733)

| Branch of service | Regiments | Regimental names |

|---|---|---|

| Guard | two | Chevaliers-Garde, Garde du Corps |

| Cuirassiers | four | Royal Prince, Prince Alexander, Pflugk, warriors |

| dragoon | six | Baudissin, Unruh, Bielke, Birkholz, Klingenberg |

| Hussars | a | no proper name |

| infantry | nine | First Guard, Second Guard, Royal Prince, Weissenfels, Diemar, Fietzner, Pflugk, Droßky, Marschall |

| artillery | House artillery, field artillery, artillery battalion | |

| Special troops | a company of pontoners , a company of miners |

After the Saxon participation in the Great Northern War ended, a peace period of over 15 years followed, which August used to create a well-trained and modern army in a far-sighted military reform. The army should be brought to a total strength of 30,000 men in order to be able to implement its foreign policy goals better than before. In January 1717 the regimental commanders also became the regimental chiefs. This should bind the senior officers closer to their soldiers. In addition, the new recruits were almost exclusively recruited from Saxony, and by order of the Saxon elector, violence could no longer be used in recruiting them. In this respect the Saxon army differed from the armies of most other German states. At the beginning of the 18th century, the Prussian army mostly consisted of foreign mercenaries who had converged or were forcibly pressed.

| Branch of service | Regiments | Regimental names |

|---|---|---|

| Cuirassiers | four | Leibdragoner, Bayreuth, Brause, Saintpaul |

| dragoon | a | Miers (henceforth the Polish Guard) |

| infantry | five | Queen, Leibregiment, Wolfersdorf, Count Moritz of Saxony, Seydlitz |

| Free Corps | Maiersche Freikorps, Heiduckenkompanie |

On August 28, 1726, a regulation of the disabled was made and a disabled corps was founded. It consisted of two battalions of four companies each. Each company had a nominal strength of 166 men. The disabled were divided into two groups, fully and semi-disabled. These soldiers only had to perform guard and occupation duties. They were used on the Saxon fortresses of Königstein , Sonnenstein , Wittenberg , Pleißenburg , Meißen , Zeitz , Waldheim , Eisleben and Wermsdorf . The corps had four officers, a lieutenant general , a major general and two colonels .

After the reforms were largely completed, the elector held a large field camp in 1730. This went down in Saxon military history under the name Zeithainer Lager . Here the monarch presented his army to the princes of Europe. At that time, the Saxon army consisted of 40 cavalry squadrons and 76 battalions of infantry. In total, this made 26,462 men. The soldier king Friedrich Wilhelm I in Prussia , who was present , noted the level of performance of the Saxon army with appreciation: “The three regiments, Crown Prince good, Weissenfeld good, very good. Pflugk very miserable, bad. Giving orders good. I have seen commands from the cavalry, which I find very proper. "

The Electoral Saxon Army was presented as follows:

| regiment | Subdivision | Manpower |

|---|---|---|

| Equestrian Guard | ||

| Chevalier Guard | a squadron | 153 |

| Grand Mousquetairs | a squadron | 165 |

| Guard du Corps | six squadrons (12 companies) | 867 |

| Guard carabiniers | six squadrons (12 companies) | 881 |

| Field cavalry | ||

| Cuirassiers | four regiments (three squadrons each) | each 579 |

| dragoon | four regiments (three squadrons each) | each 587 |

| Grenadiers on horseback | two squadrons (four companies) | 317 |

| Total cavalry | 40 squadrons (76 companies) | 7047 |

| infantry | ||

| Cadet Corps | a company | 158 |

| Swiss guard | a company | 120 |

| Grenadier Guard | one battalion (12 companies) | 1507 |

| Janissaries | one battalion (four companies) | 674 |

| Field regiments (11) | two battalions (eight companies) | each 1434 |

| Free companies | three companies | 160 each |

| artillery | one battalion (four companies) | 658 |

| Engineering corps | 44 | |

| Total infantry * | 26 battalions (111 companies) | 19,415 |

- Artillery is included in the total of infantry.

In 1732 Saxony was divided into four generalates and the troops were housed in garrisons for the first time. This once again had significant advantages in terms of disciplining, training and guiding the regiments. Until this reform, the vast majority of recruits were housed in private households. These were often poorly set up and often overcrowded. From then on, the elector also paid for the upkeep of the regiments so that there were no more cheating in the number of troops and operations of the regiments. In the course of this, the eleven infantry regiments were increased from eight to twelve companies. With the delivery of men and officers, three were formed from two companies. The company budget was reduced from 176 to 120 men. The following is a list with all regiments of the Saxon army in 1732 and their garrison towns and places of accommodation, as far as they can still be traced:

In addition, all troops from foreign rulers who were paid Saxon wages were returned. The cadet corps founded by his father was renamed the Knight Academy in 1723 . The academy was assigned its own building in Dresden. In 1732 the cadet corps moved into the house on Ritterstrasse in Dresden, which was built by Wackerbarth at their own expense and initially inhabited by Count Rutowski's life guards. From 1730 to 1733 the regulations of the army were revised again. A commission, consisting of high-ranking Saxon officers, passed regulations on the economy, armament, uniformity and the leave of absence of men.

After building up his army, Augustus the Strong tried to avoid any further war. From his bad experiences during the Great Northern War he knew that a losing battle could be the end of his hard-to-build new army. He had neither the financial means nor the inhabitants to rebuild the Saxon army. In the last years of his reign, August the Strong set up two more cuirassier regiments as well as two Chevauleger regiments and four infantry regiments. When August II died in Warsaw on February 1, 1733, he left behind a Saxon army, which was more than 26,000 strong and was of a very high standard both in the training of the soldiers and in their equipment. The Saxon army could stand up to any other European army of the time.

The War of the Polish Succession and the First Two Silesian Wars (1733–1745)

After the death of the glamorous monarch August, his son Friedrich August II (1733–1763) continued to rearm the Saxon army. Just like his father, he ran for the Polish royal crown. His strongest opponent was again Stanisław Leszczyński, who had influential supporters. In contracts with Russia and Austria, the Elector of Saxony was guaranteed the Polish crown. In 1733, the allies gathered their troops on their borders with Poland. Saxony also mobilized on June 6, 1733. Divided into two corps, 30 squadrons and 21 battalions, about 20,000 men, assembled. In the spring of 1734, the Saxons invaded Poland and, after minor skirmishes, occupied Poland. On January 17, 1734 Friedrich August II. Was named August III. appointed King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania . As a result, uprisings flared up against the new king, which were successfully suppressed by the Saxon occupation troops (see War of the Polish Succession ).

From April 1736 conduit lists were introduced for all officers. In these, service reviews were given for each officer. The conduits were divided into several headings, including whether the officer dealt properly with his subordinates, whether he was well versed in tactical matters, or whether he was subject to disciplinary vices. August III. Founded the Military Order of St. Heinrich on October 7, 1736 as a military knightly order with dynastic influences. With this award he wanted to honor officers who had distinguished themselves in the field. He was during the reign of August III. only awarded 30 times. From April 12, 1738, the four half-disabled companies were converted into five garrison companies for the five fortresses of Saxony (Wittenberg, Königstein, Sonnenstein, Stolpen and the Pleißenburg). It was also stipulated that only half-disabled soldiers, not healthy soldiers, were allowed to serve in these companies.

From October 1, 1742, a grenadier company was permanently formed in each infantry regiment. The previous procedure, that twelve grenadiers served in each company and were put together to form independent companies in the event of war, had not proven itself. From 1742, the grenadiers were trained separately and, in an emergency, deployed in independent grenadier battalions as the avant-garde of the army. At that time the grenadier had the highest priority in the Saxon infantry, the best soldiers from each infantry regiment were brought together and trained in the grenadier company. August III. continued his father's foreign policy. He tried to implement his father's dream of a great Saxon in Europe and was inevitably drawn into the Silesian Wars . The invasion of the Prussian king into neutral Saxony in 1740 left the Wettins no choice. In the First Silesian War (1741–1742), the Saxon troops forcibly fought on the side of Prussia against the Habsburg monarchy . The Saxon army provided an army of 20,000 men, which together with the Prussians and French besieged and conquered Prague in November 1741. In the following year, the Saxon army took part in minor skirmishes. On June 25th, the march back from Bohemia began over the Ore Mountains ridge near Zinnwald . The Saxon losses in this campaign were small. Three officers and ten common soldiers died during the siege of Prague, and seven officers and 54 men were wounded.

In the Second Silesian War (1744–1745), the elector initially acted neutral and let the Prussian King Friedrich II march with his troops through Saxony towards Bohemia. The elector later switched sides and fought on the side of the Austrians. In the spring of 1745 a Saxon auxiliary corps marched under the command of Duke Johann Adolf II von Weißenfels alongside the Austrian army in the direction of Silesia. The Saxon corps had 18 battalions, 20 squadrons, 30 lancers and 32 guns. In the Battle of Hohenfriedeberg on June 4, 1745, the Saxon-Austrian army was defeated by the Prussians. The army of the Saxons and Austrians had a total strength of over 71,000 men. Opposite them stood the Prussian army with about 8,000 men less. Despite the numerical superiority, the battle was lost. The losses among the Saxons amounted to 2029 dead and 915 wounded. A total of almost 4,000 men were killed, about 3,700 wounded, and a further 5,650 men were taken prisoner in Prussia. The Prussians also suffered enormous losses, 4,737 dead and wounded. Even the Saxon auxiliary corps in Bohemia, which was subordinate to the Austrians, could not withstand the Prussian army. The Saxons lost the Battle of Thrush in September 1745 on the side of the Austrians. Of the 32,000-strong army, over 6,400 were killed or wounded. The troops marching back after the Battle of Hohenfriedeberg united in November near Katholisch-Hennersdorf with the Austro-Saxon corps, which had marched north from Bohemia. The Prussian king decided to attack the army without warning. On November 23, 1745, the army attacked the unprepared Saxon-Austrian troops and destroyed the army.

The electoral troops withdrew to Dresden and took up positions near Kesselsdorf . In the following battle near Kesselsdorf on December 15, 1745, the Saxon-Austrian army under the command of Field Marshal Friedrich August Graf Rutowski suffered a crushing defeat. 14,500 soldiers were wounded or killed. Of these, the Saxon army accounted for 58 officers and 3,752 non-commissioned officers and men. Another 141 officers and 2,800 NCOs and men were taken prisoner by Prussia. That lost battle ended Saxony's last attempt to assert itself alongside Prussia. On December 18, the Saxon general Adam Heinrich Bose handed over the keys to the city to King Friedrich II. In Dresden, Frederick the Great chose 1600 of the best from the district troops of the Dresden garrison and took them with him to Prussia. He incorporated these soldiers into his guard formations. The Peace of Dresden concluded on December 25th ended the Second Silesian War.

Reduction of the army and outbreak of the Seven Years War (1745–1756)

After the Second Silesian War, the state budget of the electorate increasingly fell into the red. The lavish lifestyle of the monarch, reparations payments to Prussia and the increasing corruption at court led to a loss of income in the state treasury. Count Heinrich von Brühl , who was responsible for the affairs of state of Saxony and the state treasury, cut the Saxon army’s financial resources and reduced the number of troops. In 1746 the target number of an infantry company was only 95 men; the cuirassier regiment L'Annonciade was disbanded. In 1748, the Prime Minister had nine cavalry regiments and four infantry regiments dissolved due to lack of funds. The number of horses in the cavalry was greatly reduced. The dissolved regiments included the cuirassier regiments of Minkwitz, O'Byrn, Count Ronnow and the Dallwitz regiment, as well as the Leibdragoner, the Prinz Sondershausen regiment and the Second Guard. The regiments of Bellegarde, Jasmund and Allnpeck were affected by the infantry. The soldiers of the disbanded regiments were assigned to the remaining regiments. The infantry had a remaining stock of 20,128 men, the cavalry 10,208 horsemen, excluding 2518 Uhlans (or Tatars ), and the district troops had shrunk to 7920 men.

Despite this reduction, the two million thalers estimated for the supply and maintenance of the army were not enough. In 1749 the infantry regiments were reduced from eighteen to twelve companies and the cavalry from twelve to eight squadrons per regiment. In the infantry alone, 268 officers were decommissioned. They had to make a living from a small waiting allowance (until they were reintegrated into the army) or an even smaller pension. The payment of the wages fell more and more into arrears, so that the morale of the troops suffered greatly and the desertion increased. Although the military budget was insufficient, the military budget was reduced by a further 400,000 thalers. In 1750, each infantry company was reduced by one officer and 20 soldiers. The training of the soldiers also suffered under these conditions; between 1745 and 1753 only one field exercise was carried out. This took place in the summer of 1753 in Übigau near Dresden. The army population for this exercise was only 26,826 men including district troops.

In 1755 the target strength per cavalry company was to be reduced to 30 mounted men and per infantry company to 49 soldiers. In view of the danger of war, this measure was no longer enforced. After the loss of Silesia to Prussia, the Habsburg Marie Theresa allied herself with Russia and France against Prussia and mobilized the army in 1756. The Prime Minister Count von Brühl assured the Prussian king neutrality, but the latter knew that the Saxon court was sympathetic to the Habsburg monarchy. Due to its geographical central position, Saxony was a dangerous neighbor for Prussia, which could push the Prussian troops in the back in Bohemia or in the flank in Silesia at any time. Friedrich decided to occupy the electorate in a coup and without prior declaration of war. Count von Brühl was certain that the Prussian king would not attack Saxony. The commander in chief of the army, Count Rutowsky, warned the elector of an attack. He asked August III to be able to put the Saxon army on alert in this case and to assemble them at the troops above Pirna. On August 26th the order was given to all regiments to march to Struppen. The departure was so hasty that most regiments carried hardly any provisions or ammunition with them. Due to the financial cuts, the army was anything but ready for war and was unable to keep the soldiers' training up to date.

On September 2nd the invasion of the Prussian troops began. The army numbered 70,000 men and was divided into three columns. The center was under the supreme command of the king and marched from Jüterbog towards Torgau. The right wing was under the orders of Prince Friedrich von Braunschweig, who marched via Leipzig towards Freiberg. The left wing, under the high command of August Wilhelm von Bevern , invaded Saxony via Elsterwerda and Königsbrück. August III. went to his troops in the field camp at Struppen on September 3rd. The Saxon regiments began with fortification work to fortify the extensive camp. This was located on a plateau on the left bank of the Elbe between the Elbe and Gottleubabach, the fortified Sonnenstein and the Königstein fortress. The geographical location was reminiscent of a mountain fortress, which was only suitable for static defense. The troops had hardly any provisions and the supply routes were blocked. The army encamped in two meetings, in the first the infantry and in the second the cavalry. In this position General von Rutowsky hoped to be able to resist the Prussians long enough for the relief of the Austrian troops to reach the camp. On September 9th, Prussian troops marched into Dresden. The following day they reached the camp of the Saxon army and surrounded them. The siege army consisted of around 40,000 men, and another 23,000 lay on the Weißeritz near Dresden. The Prussian king was aware that an imperial relief army was on the way. He marched into Bohemia with the troops not needed for the siege and defeated this army, which was under the command of Field Marshal Maximilian Ulysses Browne , in the Battle of Lobositz on October 1, 1756.

The union with the Austrian troops failed, so the Saxon army had to capitulate to the overwhelming Prussian power on October 16. The Saxon army went into captivity with 18,177 men. Only the four cuirassier regiments and two Ulanenpulks stationed in Poland fought against Prussia from then on. Frederick II urgently needed soldiers in the fight against Austria, France and Russia and incorporated the regiments into the Prussian army. The first regiments marched off to the new garrisons just seven days after the surrender and surrender of arms.

Fight against Prussia, homecoming and reorganization of the army (1757–1778)

| year | date | battle |

|---|---|---|

| 1758 | October 10th | Battle of Lutterberg |

| 1759 | April 13th | Battle of Bergen |

| August 1st | Battle of Minden | |

| 1760 | July 23rd and 24th | Skirmish when attacking the Eder |

| 30th July | Battle of Warburg | |

| September 19th | Battle near Baake on the Weser | |

| 1761 | February 15th | Battle at Langensalza |

| 15th of July | Battle at Neuhaus | |

| 5th of August | Battle at Steinheim | |

| 8-11 October | Capture of Wolfenbüttel | |

| October 13th and 14th | Bombardment of Braunschweig | |

| 1762 | July | Second and Third Battle of Lutterberg |

In the spring of 1757 the desertion of the Saxon soldiers in Prussian service assumed enormous proportions. The Saxon soldiers did not feel bound by the forced Prussian oath of the flag. The regiment of Prince Friedrich August, which garrisoned in Lübben and Guben , marched out of the Prussian barracks in the direction of Poland without much resistance. Here it marched off towards Hungary. In the vicinity of Pressburg it joined the Free Saxon Corps. This was under the command of Prince Franz Xaver of Saxony . In October 1757 the corps numbered 7,731 men. Since it was not possible to march back to Saxony and the Free Saxon Army could not be paid for from its own resources, the Saxon Princess Maria Josepha placed 10,000 Saxon soldiers with the King of France. On the side of the French, the Saxons fought against the Prussians from 1758 to 1762.

On February 15, 1763, the Treaty of Hubertusburg was concluded between Prussia and its opponents. The war had led to the loss of the Polish crown and the ultimate breakdown of state finances. More than 100,000 people had been killed and 100 million thalers in war costs had arisen. Electoral Saxony had sunk to an insignificant European state at the end of the war. Electoral Saxony should henceforth lead a non-warlike policy and the army play a subordinate role.

In April 1763 the Saxon corps returned to Saxony and some of them moved into the original garrison towns. After the Seven Years' War, the Saxon army consisted of 13 infantry and twelve cavalry regiments. August III died on October 5, 1763, and his son Friedrich Christian became elector. He renounced his right to the Polish crown and wanted to concentrate on rebuilding the Electorate of Saxony and its army. Friedrich Christian died just a few weeks later, and his brother Prince Xaver, who led the Saxon corps against Prussia, took over the leadership of the electorate as administrator for Friedrich Christian's underage son, Friedrich August I (1763–1827). Under his leadership, the army was restructured and enlarged. The Prussian army served as a model for the restructuring. The infantry regiments were divided into three battalions with two grenadier and twelve musketeer companies. The target number of a regiment was 1672 senior and non-commissioned officers and soldiers.

At the army show of 1763, the infantry consisted of 9,842 men, including 651 officers. The cavalry was numbered with 4810 riders, including 336 officers. The cavalry only had 2,434 horses in their stock, so that there were two cavalrymen for one horse. The artillery had a strength of 1158 men. In the Saxon fortresses, 477 occupation soldiers were counted as a garrison. Nevertheless, in view of the financial burdens of the previous war, the regiments had only been filled to half the planned number of men by 1767. From this time onwards, garrison service in Dresden was carried out for one year by one of the infantry regiments. This should guarantee the uniform level of training of the infantry regiments. In addition, all troops performed their service temporarily in the state capital. These services also included guard duty on the various properties of the electoral family. At another army show in 1768, five years after the previous one, the total number of infantry grew to 16,449 men and the total strength of the army to 23,567 soldiers. Prince Xavier revived the Military Order of Saint Heinrich in 1768. He changed the engraved motto of the order to "Virtuti in Bello", in German "The bravery in war". He also added another class to the order. It was now divided into Grand Cross, Commander's Cross and Knight's Cross. Instead of the Polish white eagle, the Saxon diamond crown was chosen as the symbol of the order. From then on, the order was worn on a blue ribbon with a lemon-yellow edge. In 1776 a new drill regulations for the infantry were introduced.

From the War of the Bavarian Succession to the War against Napoleon (1778–1805)

uniforms around 1784 It is easy to see that from 1765 the uniform was kept completely white except for the doublure

Elector Maximilian III died in 1777 . of Bavaria without leaving an heir. From this situation, another source of fire developed in Central Europe, the War of the Bavarian Succession . The Saxon dynasty was drawn into this cabinet war as well, because it made hereditary claims on parts of Bavaria. Saxony's foreign policy finally lost its orientation and henceforth took a “zigzag path” of changing coalitions that prevailed until 1813. Together with Prussia, a Saxon army corps moved into Bohemia in the spring of 1778. The corps included ten infantry regiments, six grenadier battalions and six cavalry regiments of the Saxon army. Lieutenant General Count Friedrich Christoph zu Solms-Wildenfels was in command . The Feldjägerkorps, which had recently been founded, was used for the first time in this campaign. It had a total strength of 498 men and was based on tactics and regulations on the Prussian counterparts. The soldiers of this corps were recruited from hunters and snipers. All members of this unit were Saxons. The conflict ended in 1779 without any noteworthy armed conflict. On May 13th, 1779, in the Peace of Teschen, all hereditary claims of Saxony were settled by a one-off payment of six million guilders.

From 1780 both the infantry and the cavalry were increased in number again. In the 1770s, for financial reasons, the nominal strengths of the regiments were significantly reduced and the cavalry regiments were reduced to eight. With the beginning of the revolutionary turmoil in Europe at the end of the age of classical absolutism, many German princes and kings increased their armies. The Saxon elector also increased his army in the years 1780–1785. In 1789 the Feldjägerkorps was disbanded and the soldiers were assigned to the infantry regiments for further reinforcement. A year later, the first Saxon hussar regiment was set up on the order of the elector . The regiment had a nominal strength of 508 men and 502 horses. The riders were recruited from the other cavalry regiments. These had to make their smallest riders available to the hussar regiment. From 1780 military exercises were carried out every year. These took place near Leipzig, Dresden, Großenhein, Mühlberg and Staucha, for example. The exercises were performed in the spring until 1787, and then in the autumn of each year. The maneuvers lasted 14 days; The soldiers on leave were called up beforehand. The elector used the peacetime for general training and the adjustment of standards to those of the Prussian army, because like his predecessor, Prince Xaver, Friedrich August III was. impressed by the Prussian army and pursued a pro-Prussian foreign policy.

With the beginning of the French Revolution and the resulting conflicts between France and the German states, a Saxon contingent was mobilized in 1792. It fought alongside Prussia and Austria against revolutionary France. It consisted of five battalions of infantry, ten squadrons of cavalry and an artillery unit with the strength of ten regimental pieces and a mortar battery, a total of about 6,000 men and 3,000 horses. The Saxon corps successfully took part in the battle of Kaiserslautern . In 1794/95 the Saxon contingents remained within the Imperial Army . The contingent grew to around 9,000 men in 1795. Since the French army was advancing steadily in the west, the elector decided to separate his troops from the Rhine army and repatriate them. The march back home began in October 1795. The regiments were reinforced by further troops from the electorate and holed up on the western border of Saxony. In August 1796, non-aggression negotiations began between Saxony and France. A line of neutrality was negotiated between the states, and in September 1796 all Saxon soldiers were relocated to their home barracks. On March 17, 1796, Friedrich August III donated. the gold and silver medal of bravery of the Military Order of Saint Henry. This award was presented to deserving NCOs and men for the first time on August 2nd. In 1798 the Saxon army was set up as follows:

| Branch of service | Regiments | Regimental strength |

|---|---|---|

| Guard | Guard du Corps | 483 |

| Swiss bodyguard | 140 | |

| Life Grenadier Guard | 1122 | |

| infantry | Rgt. Elector | 1798 |

| Rgt. Von Langenau | 1798 | |

| Rgt.Prince Clemens | 1798 | |

| Rgt.Prince Anton | 1798 | |

| Rgt.Xaver | 1798 | |

| Rgt.Prince Maximilian | 1798 | |

| Rgt. Major General von Nostitz | 1798 | |

| Rgt. Major General von Zanthier | 1798 | |

| Prince Adolph Johann of Saxe-Gotha | 1798 | |

| Rgt. Major General von Lindt | 1798 | |

| Rgt. Major General von Niesemeuschel | 1798 | |

| cavalry | Carbines | 740 |

| Hussars | 1140 | |

| Chevauleger Regiment Prince of Courland | 740 | |

| Chevauleger Regiment Prince Albrecht | 740 | |

| Chevauleger Regiment von Gersdorff | 740 | |

| Chevauleger Regiment Prince of Saxony / Weimar | 740 | |

| Cuirassier Regiment Elector | 740 | |

| Zezschwitz Cuirassier Regiment | 740 | |

| artillery | Foot artillery | 1848 |

| Mounted artillery | 242 | |

| Pontooners | 1 company | 57 |

| Trains | 1 battalion | 330 |

| Engineering corps | 46 | |

| Garrison and semi-invalid | 4 companies | 608 |

| Cadet Corps | 130 | |

| Total strength 1798 | 31,644 |

In the following years the battle line-up of the Saxon army was slightly changed. As a result of the experience of the last war against France, the regiment was replaced as a combat formation by the more mobile, smaller battalion. The regiment only had a formal status. Four companies were put together to form a battalion for combat exercises. That resulted in two musketeer battalions per rent. The two grenadier companies were brought together by two regiments to form a battalion. Nevertheless, the old linear tactics of the Seven Years' War persisted. Several regulations were also changed by 1805. For example, the infantry marching speed was increased from 75 to 90 paces per minute. Furthermore, each infantry regiment received four four-pounders as artillery support and to cover the sluggish troop movements on the battlefield. The infantry were still armed with old flintlock rifles. These had a straight run and were only briefly traded. With this weapon, the focus was not on the use in combat, but on better handling when exercising. There were seldom firefighting exercises carried out by the infantry, so that the penetration power of the line infantry in the firefight was weak.

In 1800 riflemen were trained for the first time in each regiment. One corporal and the eight best riflemen per company were trained as tirailleurs . Before the fight, the tirailleurs swarmed in front of their battalions (sometimes in between) to have more space to shoot. Furthermore, if possible, they should find and occupy advantageous locations in order to have a positive influence on the course of the battle. In 1809, the 1st and 2nd Light Infantry Regiments were formed from all the riflemen in the Saxon army . This regiment became the trunk of the later rifle (fusilier) regiment "Prince Georg" (Royal Saxon) No. 108 . When Napoleon crossed the Prussian border in the autumn of 1805 and began his triumphal march against the German kingdoms and principalities, the Saxon army was mobilized on November 1st and sent to the western border.

Defeat against Napoleon and the elevation of Saxony to a kingdom (1805-1807)

| regiment | garrison |

|---|---|

| Elector | Zeitz , Borna and Weißenfels |

| by sneezing mussel | Bautzen , Görlitz and Zittau |

| from Low | Luckau , Jüterbog and Wittenberg |

| Prince Anton | Großenhain , Doberlug-Kirchhain and Kamenz , and others |

| Prince Maximilian | Chemnitz , Annaberg , Mittweida and Zschopau |

| Prince Clemens | Langensalza , Tennstedt , Thamsbrück and Weißensee |

| Prince Friedrich August | Torgau , Belgern and Oschatz |

| Prince Xavier | Naumburg , Eckartsberga , Laucha and Merseburg |

| of rights | Zwickau , Neustadt , Plauen and Schneeberg |

| Singer | Guben , Sorau and Spremberg |

| from Thümmel | Wurzen , Döbeln , Colditz , Geringswalde and Grimma |

| by Bevilaqua | Leipzig , Delitzsch and Eilenburg |

The Saxon king, who saw himself abandoned by Austria in his adherence to the imperial idea, decided to fight against Napoleon and took the side of the Prussians. From September 10, 1806, an army of 22,000 men was set up under the command of Lieutenant General von Zezschwitz to defend and secure the western border. The corps consisted of six grenadier and 19 musketeer battalions of infantry, eight heavy and 24 light squadrons of cavalry as well as seven batteries on foot and one artillery battery on horseback with a total of 50 four-pound regimental pieces. At the beginning of October the French Emperor crossed the Main with 170,000 men further east. The French faced the Prussian-Saxon army at the heights of Jena and Erfurt . In total there were 120,000 men, of which around 20,000 were Saxons. On October 14, 1806, Napoleon Bonaparte and his main army defeated the Prussian-Saxon army division Hohenlohe near Jena, while at the same time Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout and his corps, about 25 kilometers away, the clearly outnumbered Prussian main army under the Duke of Braunschweig near Auerstedt could beat. In total, the Prussians and Saxons suffered 33,000 dead, wounded and prisoners in the two battles .

In the Peace of Posen on December 11, 1806, the Saxon Elector and the French Emperor signed a separate peace. The elector undertook to make 20,000 men of the army available to the Rhine Confederation and to provide a further 6,000 men in auxiliary troops for the upcoming French campaign against Prussia. In return, the Emperor Bonaparte elevated the Electorate of Saxony to the Kingdom of Saxony. From this moment on, the correct name for the army is “Royal Saxon Army”. The Saxon corps was mobilized in early 1807 and divided into two brigades. It consisted of two grenadier and six musketeer battalions of infantry, five squadrons of cavalry and two artillery batteries of six guns each. On February 5, 1807, in a revue, the king took away the assembled corps, and the next morning it moved towards Poland. On March 7, the Saxon Auxiliary Corps was subordinated to the French X Army Corps. This was a mixed corps, consisting of French, Poles, Saxons and soldiers from the Grand Duchy of Baden . The X Army was used by Napoleon to siege the city of Danzig . On March 12, the fortress was enclosed and had to surrender on May 24. Further battles with Saxon participation in this war were the conquest of Holminsel off Danzig and the conquest of the fortress Weichselmünde .

On June 3, the French Emperor held a review of the victorious troops of the X Army Corps in Marienburg. He praised the Saxon grenadiers and their will to fight. Napoleon had the Carree formation demonstrated by the Larisch Grenadier Battalion . Despite the victorious battles with Saxon participation, the campaign was not won by the Grande Armée. The Saxon troops withdrew to Polish territory in the autumn and remained in readiness.

The wars on the side of the Grande Armée (1809–1814)

Austria, which had already been defeated by Napoleon in 1805, prepared itself again to fight the French in 1809 . As a member of the Rhine Confederation, Saxony was again forced to provide troops. The king mobilized his army in February 1809. On March 7th, Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte took over command of the Saxon contingent, which was divided into two divisions and formed as the 9th Army Corps in the Rheinbund army. The corps was about 16,000 strong. In this war, all Saxon riflemen were combined into an independent association for the first time. The battles with Saxon participation in this war were the siege of Linz, the battle of Dornach and the battle of Wagram . The Saxons paid dearly for victory in the Battle of Wagram. After the two-day battle, 132 officers and 4103 NCOs and commoners were dead, wounded or missing.

On the basis of an already improved drill regulations for the infantry in 1804 (the main point of which was the faster march with 90 instead of the previous 75 steps per minute and after which the maneuvers were won by the royal party according to plan) and according to the excellent French infantry regulations of 1808, Lieutenant General Karl Christian Erdmann from Le Coq , the major general Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Funck , Karl von Gersdorff and Johann Adolf von Thielmann as well as Colonel Friedrich von Langenau the new Saxon regulations in the spring of 1810. This was officially put into effect on May 1, 1810.

Further changes as part of the Saxon military reforms:

- Rejuvenation of the officer corps

- Reducing the number of surgical staff while improving military medicine

- No rifles for officers - instead, duty with drawn swords

- Handing over of the flags of the artillery to the main armory - swearing in of the crew only on the cannon

- Dissolution of the staff battalion established in the meantime (1809)

- Improvement of the military justice system - Right of higher officers to have a say in criminal matters - Prohibition of corporal punishment as a punishment

- Change of uniform according to the French pattern and introduction of new rifles, bayonets and side arms

- Training in a new way of fencing: columns with swarms of screechers instead of the old, rigid form of linear tactics

- Introduction of the first drill regulations for the artillery

- Instead of domestic advertising with recruitment, now nationwide recruitment with district commissions as a replacement system with a fixed period of ten or eight years for the recruits

The Royal Saxon Army experienced an upswing through this reorganization. In addition, with the reorganization, the previously familiar company economy was ended. The new army administration brought about completely changed conditions with regard to food, clothing and equipment for the troops. The supreme command of the renewed army was nominally headed by the king. In 1810 Major General Heinrich von Cerrini di Monte Varchi was Minister of War, Major General von Gersdorff Chief of Staff . As a result of this military reform, the Royal Saxon Army was structured as follows at the beginning of the year:

-

1st Infantry Division , under the command of Lieutenant General von Zeschau, division headquarters in Dresden

- the General Staff in Dresden is subordinate to the Leibgrenadiergarde

-

1st Brigade , Major General von Dryherrn, Brigade Staff in Dresden

- König Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- Niesemeuschel Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- from both regiments the grenadier regiment (four companies)

-

2nd Brigade , Major General von Nostitz, Brigade Staff in Bautzen

- Prince Anton Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- Low Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- from both regiments the grenadier regiment (four companies)

-

2nd Infantry Division , under the command of Lieutenant General Karl Christian Erdmann von Le Coq , division headquarters in Dresden

-

1st Brigade , Major General von Klengel, Brigade Staff in Chemnitz

- Prince Maximillian Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- Infantry regiment from the right with 2073 men

- from both regiments the grenadier regiment (four companies)

-

2nd Brigade , Major General von Steindel, Brigade Staff in Eilenburg

- Prince Friedrich August Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- Prince Clemens Infantry Regiment with 2073 men

- from both regiments the grenadier regiment (four companies)

-

1st Brigade , Major General von Klengel, Brigade Staff in Chemnitz

-

Brigade Light Infantry , under the command of Major General Saher von Sahr, brigade staff in Zeitz

- 1st regiment of light infantry with 1,652 men

- 2nd light infantry regiment with 1,652 men

- Jäger corps with 124 men

-

Cavalry division , under the command of Lieutenant General Freiherr von Gutschmidt, division headquarters in Dresden

- the Guard du Corps is subordinate to the General Staff in Dresden

-

1st Brigade , Lieutenant General von Funk, Brigade Staff in Pegau

- Chevauxleger Regiment Prinz Clemens with 768 men and 718 horses

- Chevauxleger regiment from Polenz with 768 men and 718 horses

- Hussar regiment with 1065 men and 1002 horses

-

2nd Brigade , Lieutenant General Thielemann, Brigade Staff in Dresden

- Personal cuirassier guard with 768 men and 718 horses

- Zastrow cuirassier regiment with 768 men and 718 horses

-

3rd Brigade , Major General von Barner

- Chevauxleger regiment Prinz Johann with 768 men and 718 horses

- Chevauxleger regiment Prinz Albrecht with 768 men and 718 horses

- Artillery brigade on horseback with 242 men and 226 horses

Subordinate to the General Staff in Dresden:

- Foot artillery with 1848 men

- Cadet Corps

- Royal Swiss Guard

- Geniuses with engineering corps

- Sappers and pontoniers (the later engineer troops)

- Garrison companies such as the semi-disabled companies made up of those not fit for field service

Overall, the army had a budgetary strength of 36 cavalry squadrons with a total of 6577 men, 31 infantry battalions or artillery brigades with a total of 24,937 men and an exiled corps with 266 men, all in all 31,780 men. When the army was reorganized, the carabiniers and the four infantry regiments Oebschelwitz, Cerrini, Burgdorf and Dryherrn were disbanded and divided among the other regiments. The newly formed regiments were assigned the following garrison towns in the kingdom:

| regiment | garrison |

|---|---|

| Life Grenadier Guard | Dresden |

| 1st Line Infantry Regiment König | Dresden and Großenhain |

| 2nd Line Infantry Regiment vacant Sneeze mussel | Dresden and Großenhain |

| 3rd Line Infantry Regiment Prince Anton | Bautzen, Görlitz and Sorau |

| 4th Line Infantry Regiment vacant Low | Luckau, Guben and Sorau |

| 5th Line Infantry Regiment Prince Maximilian | Chemnitz, Döbeln and Freiberg |

| 6th Line Infantry Regiment vacant right | Zwickau, Neustädtel and Sorau |

| 7th Line Infantry Regiment Prince Friedrich August | Torgau, Oschatz and Wittenberg |

| 8th Line Infantry Regiment Prince Clemens | Leipzig, Eilenburg and Wittenberg |

| 1st Light Infantry Regiment | Zeitz and Weißenfels |

| 2nd light infantry regiment | Naumburg and Merseburg |

| Hunter Corps | Eckartsberga |

| regiment | garrison |

|---|---|

| Guard du Corps | Dresden, Dippoldiswalde, Pirna and Radeberg |

| Personal cuirassier guard | Oederan, Frankenberg, Marienberg and Penig |

| Zastrow cuirassiers | Grimma, Borna, Geithain and Rochlitz |

| Hussar Regiment | Cölleda, Altenstädt, Artern, Bretleben, Bottendorf , Heldrungen , Langensalza, Roßleben , Schönewerda , Schönfeld and Wiehe |

| Chevauxleger regiment Prince Clemens | Pegau, Lützen, Schkeuditz and Zwenkau |

| Chevauxlegerregiment vacant Polenz | Querfurt , Freyburg , Schafstädt and Sangerhausen |

| Chevauxleger regiment Prince Johann | Mühlberg, Düben, Kemberg and Schmiedeberg |

| Chevauxleger regiment Prince Albrecht | Lübben, Cottbus and Lübbenau |

On February 15, 1812, the army mobilized for Napoleon's upcoming Russian campaign . The Saxon contingent took part in this campaign as 21st and 22nd divisions of the VII Army Corps of the Grande Armée under the command of the French division general Count Jean-Louis-Ebenezer Reynier - who always had a heart for his soldiers from Saxony. Overall, the Saxons set 18 infantry battalions , 28 cavalry squadrons , 56 (six- and four-pounders) -Geschütze together, these were 21,200 men and 7,000 horses. In March 1812 the Saxons marched from their field quarters near Guben in the direction of Russia. During this march, on the orders of the emperor, the guard regiment Garde du Corps and the cuirassier regiment von Zastrow as well as the mounted artillery battery von Hiller were detached from the Saxon association and added to the IV Cavalry Corps as Brigade Thielmann with the Polish cuirassiers . This was 2070 strong and took part in the advance on the Russian capital Moscow . Half of this brigade was destroyed in the Battle of the Moskva , but the Garde du Corps was the first to penetrate the Russian main hill. The remnants marched into Moscow on September 14th with Marshal Murat.

The Russian campaign ended catastrophically for the Saxon army. In January 1813 there was not much left of the 28,000-strong army. Worst of all were the losses of the cavalry regiments. From the Garde du Corps regiment and the Zastrow cuirassier regiment, only about 70 soldiers survived. The Chevauxleger regiment Prinz Albrecht also experienced total annihilation, of the 628 riders only 30 returned home. The two infantry regiments von Rechten and Low and the Chevauxleger regiment Prinz Johann went to war with special orders. They came under the leadership of Marshal Victor until Smolensk . Here the marshal's army was ordered to secure the retreat after a battle. The remaining 200 riders of the Prince Johann Regiment went into captivity, only 100 of the infantry regiments survived. These withdrew to the Berezina. Another 40 men were killed in the battle of the Beresina . The number of regiments dwindled steadily. On December 20, the last members of the regiments were taken prisoner. Only ten officers returned from the Regiment of Right; six officers returned from the Low regiment.

Of the two light infantry regiments, only barely one battalion remained in December 1812. In order to at least regain the strength of the battalion, all Saxon infantry regiments had to deploy soldiers for the light battalions. This Saxon corps also suffered enormous losses in the course of the campaign. In addition to the losses in the battles around the Bug in November 1812, thousands of soldiers of the VII Army Corps froze to death on the march back to Berezina. Of the Saxon army, only 1,436 survived.

The Wars of Liberation (1813-1815)

After the defeat of the Grande Armée in Russia, the wars of liberation began . On the side of Russia, Prussia openly took up the fight against Napoleonic foreign rule. Napoleon demanded new troops from the Confederation of the Rhine to fight the two-party alliance. Saxony complied with the demand and set up a new Saxon army under General von Thielmann near Torgau. In May 1813 Thielmann had already put 8,000 Saxons under arms again. In order to make the regiments that were quickly set up ready for action, Thielmann distributed the surviving veterans from the Russian campaign to the newly established units.

Although the Saxon king also wanted to terminate the alliance with the emperor, the French initial successes resulted in the Battle of Großgörschen on May 2nd and the Battle of Bautzen on May 20th / 21st. May added that the king believed in a victory of Napoleon, and so Saxony remained in the Rhine Confederation even after the armistice of Pläswitz expired , while Austria joined the Prussian-Russian alliance. In the autumn campaign that followed, the French and Saxons under Reynier were defeated in the Battle of Großbeeren on August 23, 1813. As a result, the French also lost the Battle of Hagelberg . On August 26 and 27, Napoleon repulsed the attack of the main army of the allies on the Saxon capital in the battle of Dresden . This battle was the last victory of the French emperor on German soil. The Battle of Dennewitz took place on September 6, 1813. In this battle, the French, Saxons and the troops of the Confederation of the Rhine under the command of Marshal Michel Ney were crushed. The marshal wrote to his emperor that he was completely defeated and that his army no longer existed. The Saxons had 28 officers and 3,100 men killed, wounded and captured in this battle. Marshal Ney then blamed the defeat on the Saxons.

The Battle of the Nations near Leipzig brought the end of the war of liberation on Saxon soil . At the beginning of the battle, the Saxons were still on the side of the French emperor. The Saxons changed sides in the course of the battle and from then on played no role in this battle. After the Battle of Nations, the remnants of the Saxon regiments were placed under the command of General von Ryssel. From November 2nd to 14th, the Saxons were used to siege the Torgau Fortress . After that, the corps gathered near Merseburg for reorganization. This task was again assigned to General von Thielmann.

three line infantry regiments

- three battalions as a provisional guard regiment

- 1st Battalion, the previous Leibgrenadiergarderegiment

- 2nd battalion, remnants of the König battalion

- 3rd Battalion, formed from all the grenadiers of all infantry regiments still available

- two battalions as the provisional 1st Saxon line infantry regiment

- 2nd battalion

- 3rd Battalion, both battalions were primarily formed from the Prince Anton Regiment

- two battalions as the provisional 2nd Saxon line infantry regiment

- 2nd battalion

- 3rd Battalion, these battalions were formed from the remnants of the regiments of Prinz Maximilian and the disbanded regiments of Rechten and Seidel

- two battalions of 1st Light Infantry (Rifle) Regiment

- 1st Battalion, from the previous Le Coq regiment

- 2nd battalion, from stocks of old reservists and riflemen who have returned from captivity

- a battalion of the 2nd Light Infantry (Rifle) Regiment

- 2nd battalion, formed from the previous Sahrer von Sahr regiment; the 1st battalion was later formed from the returning soldiers of the regiment and moved out later

- a battalion of hunters

nine squadrons of cavalry

- three squadrons of cuirassiers

- three squadrons of Uhlans

- three squadrons of hussars

In the spring of 1814 another four squadrons moved away (one squadron each of cuirassiers and lancers and two squadrons of hussars). These were formed from the prisoners who had returned from the cavalry regiments.

artillery

- two foot artillery batteries of eight guns each

- two mounted artillery batteries with six guns each

other troops

- a company of pioneers (joined the army corps on March 16)

- a company of bridge trains

After the reorganization by Thielmann, the population of the Saxon army was around 9,000 men and 1,600 horses. In addition, were Landwehr organized -Infanterieregimenter (first four regiments of two battalions) and banners of volunteers (two battalions of light infantry and five squadrons of cavalry).

On December 3, the Saxon Army joined the 3rd German Army Corps and took part in the campaign against France. The Saxons were placed under the command of Karl August von Sachsen-Weimar . On February 2, the Saxon army marched west under the command of General Le Coq. The 3rd Corps was reinforced by a fusilier battalion from the Duchy of Saxony-Weimar and an infantry brigade from the Duchy of Anhalt . The Saxon part of this corps at the beginning of the campaign was eleven battalions of infantry, nine squadrons of cavalry and 28 artillery riflemen. In March General von Thielmann arrived with another 7,000 men in the 3rd Army Corps. The Saxon corps then moved to Maubeuge fortress and besieged it from March 21st. Other Saxon troops took part in the siege of Antwerp . With the conquest of Paris and the fall of Napoleon, General Nicolas-Joseph Maison signed an armistice and ended the spring campaign of 1814. In June 1814, the third recruiting corps arrived in Flanders. The 3rd Army Corps was deployed in Flanders as an army of occupation. The Saxon corps in France was structured as follows:

| Branch of service | regiment | Manpower | Branch of service | regiment | Manpower | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| infantry | Grenadier Regiment | 2250 | artillery | three six-pound batteries | 24 guns | |

| 1st Provisional Infantry Regiment | 2250 | two batteries on horseback | 12 guns | |||

| 2nd Provisional Infantry Regiment | 2250 | Special troops | a company of pioneers | |||

| 3rd Provisional Infantry Regiment | 750 | a company of carts | ||||

| Jäger Battalion | 750 | a field hospital | ||||

| 1st Light Infantry Regiment | 1500 | a squadron of staff dragons | ||||

| 2. Light Infantry Regiment | 1500 | |||||

| cavalry | Cuirassier Regiment | 600 | ||||

| Uhlan Regiment | 525 | |||||

| Hussar Regiment | 750 |

- Commanding general of the army corps: Lieutenant General von Thielmann

- Chief of Staff: Colonel von Zezschwitz

- Infantry Commander: Lieutenant General Le Coq

- Commander of the cavalry: Colonel Leysser

- Commander of the artillery: Colonel Raabe

Overall, the Saxon corps had grown to 16,000 line infantry, 2,000 cavalrymen and 36 artillery pieces.

At the turn of the year 1814–1815 the corps took up positions near Cologne and Kempen . The corps headquarters was relocated to Bonn .

Division of the army, peacetime until 1848

During the negotiations at the Congress of Vienna , the partition of Saxony was decided. The northern part of Saxony went to Prussia. As a result, on May 1, the Saxon corps was divided into two brigades. The division was based on the place of birth, because all Saxon soldiers who were born in the new Prussian territory had to join the Prussian army. In the course of this restructuring of the troops, there were multiple riots and refusals of orders by entire regiments. From the provisional Guards regiment in seven ringleaders of a smaller revolt against superiors were by a military court sentenced to death and summarily shot . On May 17, all companies were divided into two half companies (one South Saxon and one North Saxon). The division was officially completed on June 13th. On the Saxon side, this was carried out by Lieutenant General Le Coq. 6807 officers, NCOs and men went over to the Prussian military service. 7,968 soldiers remained with the Saxon corps. The Saxon corps was reorganized once again and on July 7th consisted of:

| Branch of service | regiment |

|---|---|

| infantry | 1st Provisional Infantry Regiment |

| 2nd Provisional Infantry Regiment | |

| 3rd Provisional Infantry Regiment | |

| 3rd Provisional Infantry Regiment | |

| Jäger Battalion | |

| Light infantry regiment | |

| cavalry | Body Cuirassier Guard Regiment |

| Ulan regiment | |

| Hussar Regiment | |

| artillery | four six-pound batteries |

| two batteries on horseback |

The mobile army corps marched on July 8th towards the Upper Rhine and united with the army corps of the Austrian Prince von Schwarzenberg. From this point on, the corps was under the command of Colonel von Seydewitz, since Lieutenant General von Le Coq had transferred to Russian military service.

During the rule of Napoleon's Hundred Days and the following summer campaign of 1815 , Saxon units were used to siege Schlettstadt and to observe the town of Neu-Breisach . The Saxon corps was relocated to the Nord department in January 1816 . In the Second Peace of Paris France was obliged to pay 700 million francs in war compensation. The troops of the victorious powers occupied France until 1819. In December 1818, the Saxon troops marched home. The commander in chief of the occupation forces in the North Department, General Arthur Wellington , said goodbye to the Saxons with benevolent words. In the past three years he has never received any negative reports about the Saxon troops, and their reliability was always valued by the Allies.