Bitterfeld

|

Bitterfeld

City of Bitterfeld-Wolfen

|

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 51 ° 37 ′ 35 ″ N , 12 ° 19 ′ 40 ″ E | |

| Area : | 27.85 km² |

| Residents : | 15,125 (June 30, 2017) |

| Population density : | 543 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation : | July 1, 2007 |

| Postcodes : | 06766, 06749 |

| Primaries : | 03493, 03494 |

Bitterfeld is a district of the city of Bitterfeld-Wolfen in the Anhalt-Bitterfeld district in Saxony-Anhalt and a center of the chemical industry. Until June 30, 2007, Bitterfeld was an independent town and district town of the Bitterfeld district . Bitterfeld is located about 25 km northeast of Halle (Saale) and about 35 km north of Leipzig . To the east is the Muldestausee . The district of Wolfen joins in the north and the Goitzsche with the Great Goitzschesee to the southeast of the city , a nature reserve with 24 km² of water.

geography

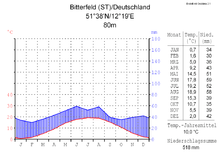

climate

The average air temperature in Bitterfeld is 10.0 ° C and the annual precipitation is 516 millimeters. It is extremely low, falling in the lower twentieth of the values recorded in Germany. The driest month is February, with the most rainfall in June. In June there is twice as much precipitation as in February. The rainfall hardly varies and is evenly distributed over the year.

history

development

The name probably comes from the Middle High German meaning “swampy” of the adjective bitter and therefore means “swampy land”.

Bitterfeld was once located in a Slavic settlement area. It is first mentioned in a document on June 28, 1224. Until 1276, Bitterfeld belonged to Anhalt . In the Middle Ages, Bitterfeld was a small town that lived from handicrafts and agriculture, mainly cloth makers, potters and cobblers, and from its beer breweries.

In 1621, Bitterfeld had a tipper mint in which interim coins (tipper coins) were struck under mint master Barthel Eckardt. These were tipper groschen and cruiser pieces as well as Kipper Schreckenberger .

During the Thirty Years' War the place was sacked by the Swedes in 1637. The city was the seat of the office of Bitterfeld in the Electorate of Saxony and was assigned to the newly formed Prussian province of Saxony in the course of the Vienna Congress in 1815 and the seat of the district office of the Bitterfeld district .

The economic development occurred in Bitterfeld by industrial development and connection to the railway network by 1857. The region was to explore the lignite deposits for Bitterfeld mining area , which resulted in the lignite mining by open pit created many "pits". Some of these were later filled with household waste or used as a lake due to rising groundwater. Well-known examples of this are the Goitzsche or the “Postgrube” lake near Zscherndorf .

Before the Second World War , Bitterfeld was a modern industrial center in which substances essential to the war effort were also manufactured. At the time of National Socialism , several hundred prisoners of war and women and men of various nationalities had to do forced labor in the city's chemical and armaments factories until 1945 . In the final phase of the GDR , the region became a symbol of the ailing equipment of the economy and dangerous environmental pollution , as the modernization of the industrial facilities was neglected and the pollution of the environment continued as it did at the beginning of the 20th century. The accumulation of toxins through environmentally destructive economic activity, especially during the two world wars, resulted in considerable damage to the environment. In those years the city was given the unflattering title of “Dirtiest City in Europe”. As if viewed through a special color filter, a monochrome, greyish-brown-green glaze lay over houses, countryside and factories.

Bitterfeld is one of the most important centers of the popular uprising against the SED dictatorship. On June 17, 1953, up to 50,000 people demonstrated on the central youth square and the Binnengartenwiese - more than Bitterfeld's population at the time. The teacher Wilhelm Fiebelkorn read out a telegram to the government of the GDR demanding the immediate resignation of the government, free elections and the release of political prisoners. The strike committee, to which the electrician Paul Othma , arrested on June 20 as a "ringleader", belonged, deposed Mayor Heinz-Rudolf Strauch. Demonstrators occupied the SED district leadership and the MfS building and read the names of informers.

On April 24, 1959, the first authors' conference of the Mitteldeutscher Verlag, later known as Bitterfelder Weg , took place in the Kulturpalast of the VEB Elektrochemisches Kombinat Bitterfeld , where it was to be clarified how working people can be given active access to art and culture. The “existing separation of art and life” and the “alienation between artist and people” should be overcome. A second conference followed in 1964.

On July 11, 1968, Bitterfeld was shaken by a huge explosion. A detonation occurred in the PVC hall of the chemical combine. 42 of the 57 workers in the hall died immediately, 200 people had to receive medical care. Large parts of the plant were destroyed. Responsible company and party committees tried to ensure that this event did not become public knowledge, which also failed in the city due to the destruction. (→ Chemical accident in Bitterfeld )

Between 1974 and 1993, amber was mined in open-cast mining in Bitterfeld , initially by hand, and from 1976 by machine.

On September 27, 1988, the ARD magazine Kontraste drew attention to the environmental pollution of the region, especially using the example of the Silbersee in the neighboring town of Wolfen (the ORWO film factory disposed of various waste in this residual hole of the Johannes open-cast mine ) - with the contribution bitter Bitterfeld by Rainer Hällfritzsch, Ulrike Hemberger and Margit Miosga with the collaboration of Hans Zimmermann from Bitterfeld and Ulrich Neumann from East Berlin from the green-ecological network Arche . After the Peaceful Revolution of 1989, many industrial closures followed. Figuratively speaking, people, plants and nature could breathe easy again. Even if the loss of many jobs meant an enormous burden for the people, it was now possible to think about making the battered region more livable again. With recultivation efforts worth billions , the post-mining landscape around Bitterfeld was transformed into a forest and lake landscape, which is now a destination for hikers and water sports enthusiasts. Little by little it can be observed how nature overgrows its old scars. Monika Maron portrayed the extremely difficult production conditions in Bitterfeld chemical plants in her novel Fly ash and 30 years later showed the further development described in her report Bitterfelder Bogen .

Despite the closure of many industrial companies and economic problems, Bitterfeld is still an important location for the chemical industry as part of the " Central German Chemical Triangle " around Halle (Saale) and Leipzig with the new "Chemical Park" (see below) . In 2000, Bitterfeld was a correspondence region of the Expo 2000 in Hanover . One of the Expo results still visible today is the August von Parseval vocational school center . It was put into use in 2000.

City merger 2007

On July 1, 2007, Bitterfeld merged with the neighboring town of Wolfen and the municipalities of Greppin , Holzweißig and Thalheim to form the newly founded town of Bitterfeld-Wolfen. The city of Bitterfeld-Wolfen merged with Bobbau as planned on September 1, 2009 (according to a public hearing, 54 percent of Bobbau's residents were against the merger with Bitterfeld-Wolfen). The city of Bitterfeld-Wolfen had around 45,000 inhabitants at the end of 2010, making it the fifth largest city in Saxony-Anhalt. In addition, in the course of the regional reform in Saxony-Anhalt, the districts of Bitterfeld and Köthen merged with large parts of the district of Anhalt-Zerbst to form the district of Anhalt-Bitterfeld .

Bitterfeld syndrome

The Bitterfeld syndrome , which is officially called contaminated site syndrome in the classification , describes anthropogenic soil degradation through local contamination, waste accumulation and contaminated sites. This syndrome was first diagnosed in Bitterfeld in the 1990s. The reasons for the severe environmental problems in Bitterfeld lay in the settlement of the chemical industry without adequate environmental protection measures. This leads to ecological disturbances and increased health risks for humans. Bitterfeld syndrome was also diagnosed for the regions of Cubatão (Brazil), the Donets Basin (Ukraine), Katowice (Poland), Wallonia (Belgium), Manchester - Liverpool - Birmingham (Great Britain), Seveso (Italy), Bhopal (India), Hanford and Pittsburgh (USA).

Population development

| date | Residents |

|---|---|

| December 31, 1840 | 4,649 |

| December 31, 1870 | 5,693 |

| December 31, 1880 | 6,531 |

| December 31, 1890 | 9,047 |

| December 31, 1925 | 18,384 |

| December 31, 1933 | 21,328 |

| December 31, 1939 | 23,949 |

| October 29, 1946 | 32,833 |

| date | Residents |

|---|---|

| 08/31/1950 | 32,814 |

| December 31, 1960 | 31,687 |

| December 31, 1981 | 22,199 |

| December 31, 1984 | 21,279 |

| 10/03/1990 | 18,099 |

| December 31, 1995 | 16,868 |

| December 31, 2000 | 16,507 |

| December 31, 2001 | 16,237 |

| date | Residents |

|---|---|

| December 31, 2002 | 15,985 |

| 12/31/2003 | 15,798 |

| December 31, 2004 | 15,755 |

| December 31, 2005 | 15,728 |

| 06/30/2006 | 15,709 |

| 06/30/2017 | 15,125 |

* Data source from 1995: State Statistical Office Saxony-Anhalt

politics

In the state elections in Saxony-Anhalt in 2016 , the AfD achieved the best result nationwide in constituency 29 (Bitterfeld) with 33.4% of the first votes and 31.9% of the second votes.

Town twinning

Bitterfeld maintains city partnerships with the following cities:

-

Marl (Germany, North Rhine-Westphalia )

Marl (Germany, North Rhine-Westphalia )

-

Dzerzhinsk (Russia), since 1996

Dzerzhinsk (Russia), since 1996 -

Kamienna Góra (Poland), since 2006

Kamienna Góra (Poland), since 2006 -

Vierzon (France), since 1959

Vierzon (France), since 1959

Local council

The local council of the Bitterfeld district has 19 seats. The last election to the local council on May 25, 2014 resulted in the following distribution of seats:

| The left | 7 seats |

| CDU | 6 seats |

| SPD | 2 seats |

| Voters list sport ( free voters ) | 2 seats |

| AfD | 2 seats |

flag

The flag is striped red and white. The city coat of arms is placed in the middle of the flag.

coat of arms

The coat of arms was approved by the Dessau regional council on February 14, 2000 and registered in the Magdeburg State Archives under the coat of arms roll number 4/2000. Blazon : “In silver on a curved green shield ground, a red round tower with a green, red crossed pointed roof and an open arched window over an open arched gate; the tower is surrounded by a floating triangular shield, right: divided nine times by black over gold, covered diagonally to the right with a green diamond wreath (Saxony), left: in silver three (2: 1) red sea leaves (Counts von Brehna) ”. The coat of arms was redesigned by the Magdeburg municipal heraldist Jörg Mantzsch .

Culture and sights

Buildings

- “Fürstenherberge” (1579), two-storey half-timbered building, now plastered, with a Renaissance portal

- Town hall (1863–1865), neo-Gothic brick building based on a design by August Friedrich Ritter

- Villa am Bernsteinsee (1896), manufacturer's villa in the neo-renaissance style

- Roman Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (1896), neo-Gothic

- Protestant St. Antonius Church (1905–1910), neo-Gothic brick building

- Park in the inner gardens, called "Green Lung"

- Kulturpalast (1954), where the “ Bitterfelder Weg ” was announced in 1959 ; 2004 renovated since 2015 unused and threatened with demolition

- only artificial, later flooded by high water open pit " Goitzsche " (called "Bernsteinsee") to the level tower and water front

- Vocational school center August von Parseval Bitterfeld-Wolfen (2000), largest low-energy building in Germany at the time of construction, planning and execution by scholl architects gmbh (Stuttgart)

- High-speed clothoid turnouts on the Berlin – Halle railway line , passable at 330 km / h on the straight track and 220 km / h on the branching track, Germany-wide technical feature

- Bitterfelder Bogen (2006), large accessible sculpture, landmark and vantage point on the Bitterfelder Berg, designed by the German sculptor Claus Bury

Monuments

- Memorials to the fallen in 1870/71 (inland gardens) and 1914/18 (inland gardens), demolished and built over after 1945

- Memorial plaque commemorating the March fights in 1921 at the town hall entrance on the market side

- Memorial stone (1962) on a green area in Dessauer Straße in memory of the communist party chairman Ernst Thälmann , who appeared several times as a speaker in the Red Front Fighters League in Bitterfeld . Another stone and two panels are located on the grounds of the Concordia ballroom

- Memorial (1951) for the victims of fascism on the new cemetery at Friedensstrasse 43 with the mass graves of 43 forced laborers , six unknown concentration camp prisoners on a death march , a Polish Nazi victim and two German resistance fighters against National Socialism

- Soviet memorial (1949) in the New Cemetery for 60 forced laborers, 60 prisoners of war and 69 deceased Red Army soldiers

- Memorial stone (1950) in the former chemical combine, intersection B183 / B184 (“acid crossing”), for six murdered Soviet prisoners of war

- Plaque (1950) on the main workshop of the former Kombinat in memory of the anti-fascists Paul Schiebel , in 1943 in the penitentiary Brandenburg-Gorden was murdered

- Memorial plaque (1981) in Dürener Straße (Richard-Stahn-Straße during the GDR era) in memory of the communist Richard Stahn , who was murdered in Buchenwald concentration camp in 1938 and who was also remembered by the name of an auxiliary school at Hahnstückweg 4

- Memorial plaque (2003) on the Bitterfeld town hall for Paul Othma (1905–1969), strike leader of June 17, 1953, who died as a result of his eleven and a half years of political imprisonment.

Museums

The district museum, which was built as a school building in the city center in 1839, houses permanent exhibitions on regional history, geology, biology and archeology. In addition, a permanent exhibition is dedicated to balloon flights, which in Bitterfeld can look back on a 90-year tradition. In the basement there is a permanent exhibition on Bitterfeld amber, which describes the only German amber deposit that was being mined after the Second World War.

Sports

Twice found in Bitterfeld the FAI World Gas Balloon Championship , the gas balloon World Championship instead. In 1996 the German team led by Thomas Fink and copilot Rainer Hassold from Augsburg won with the GER 1. Ballon. In 2004, the last gas balloon world championship took place in Bitterfeld after eight years. Again a German team won.

Since the 2010/2011 season, Bitterfeld has been represented with the BSW Sixers in the 2nd Bundesliga Pro B basketball.

The volleyball men of VC Bitterfeld-Wolfen have been playing in the 2nd Bundesliga North since 2012 .

Economy and Infrastructure

development

With the start of open- cast lignite mining south of Bitterfeld in 1839, the town enjoyed a rapid economic boom. The layers of clay overlying the coal fields encouraged rapid growth in the stoneware industry, which, along with that in the Rhineland, was one of the most important in the German Empire. In 1893, Walther Rathenau set up the electrochemical works, followed in the same year by the Griesheim chemical factory as another electrochemical company . This laid the foundation for Bitterfeld as the most important place in European chlorine chemistry . The decisive reason for the settlement was the extensive and inexpensive coal deposits, which were required for the production of electrical energy. The chemical industry expanded enormously and gained in importance during the First World War , when Germany, which was poor in natural resources, was forced to create chemical substitutes. One of the largest aluminum smelters was built in Bitterfeld in 1915 , and large power plants were built next to it . Even the brown coal surface mining expanded rapidly, which had a negative impact on the landscape. With the formation of IG Farbenindustrie AG in 1925, Bitterfeld became the headquarters of IG Farben's Central German Working Group from 1926. In the following years the lignite mines came into the possession of IG Farben.

After the end of the war, the companies were transferred to Soviet joint-stock companies in 1946 and then transferred to the GDR as state-owned companies. In Bitterfeld, the VEB Elektrochemisches Kombinat Bitterfeld (EKB) was created, which in 1969 became the VEB Chemiekombinat Bitterfeld (CKB). With the VEB Industrie- und Kraftwerkrohrleitungsbau Bitterfeld (IKR), Bitterfeld housed another important enterprise of the GDR economy. The stoneware works were transferred to the VEB Steinzeugwerke Bitterfeld , which existed until 1959. Another important company was the lignite combine Bitterfeld (BKK), which, in addition to the opencast mines in the region, operated an extensive railway network for the removal of the extracted lignite. The environmental problems caused by the Bitterfeld industry due to a very old equipment without environmental protection measures are legendary. Striking, but not entirely without cause, Bitterfeld has therefore been called the “dirtiest city in Europe”.

In 1990, large-scale industrial operations were shut down and lignite mining ended. Most of the opencast mines were flooded and renatured with considerable funding. The chemical industry site was privatized, and the companies that had emerged from it continued Bitterfeld's tradition as an important chemical location together with well-known new settlers ( Bayer , Heraeus , Akzo Nobel , Degussa ). For example, almost all aspirin tablets for the European market are produced at Bayer's Bitterfeld plant. A composite of materials proves to be a locational advantage, which is carried out via a widely branched pipe bridge system within the chemical park between different neighboring residents, especially in the area of chlorine chemistry . The political change in 1989/1990 and the subsequent reorganization and privatization of industry led to unemployment of over 20 percent, which was mitigated by measures by the Federal Employment Agency .

The establishment of the Q-Cells Group with its subsidiaries made Bitterfeld-Wolfen and the neighboring Thalheim a world center of the solar industry. More than 3000 people were once employed in the so-called Solar Valley . Due to the increasing competition from Asia, Q-Cells filed for bankruptcy with the subsidiary Solibro and Sovello in 2012. Until the end of 2015, Solibro was part of the Chinese Hanergy Holding Group. Solibro Hi-Tech GmbH and Solibro Research AB remained with Hanergy. Q-Cells was sold to the South Korean group Hanwha. No investor was found for Sovello and the formation of a transfer company for the employees failed.

Companies

The following companies (selection) are located in the Bitterfeld-Wolfen Chemical Park , which was established in 2001 and also extends over the districts of Wolfen, Thalheim and Greppin: Akzo Nobel Chemicals GmbH, Bayer Bitterfeld GmbH , Degussa AG, Dow Wolff Cellulosics , Heraeus Tenevo AG / Heraeus Quarzglas GmbH & Co. KG , Lanxess Deutschland GmbH , Linde AG Linde Gas division, Q-Cells SE (today Global PVQ SE) and Solibro GmbH.

traffic

The Bitterfeld district was connected to a regular network of roads in 1823 with a connection to the Chaussee from Berlin via Halle to Kassel . Its course corresponds to that of today's federal highway 100 in the district .

The Magdeburg – Halle (Saale) –Leipzig railway line, opened in 1840, connected the Bitterfeld district to the still young German railway network. However, it was of little use as the line only touched the western part of the circle. The situation improved when Bitterfeld received a rail connection to Dessau in 1857 and was connected to the network of the Berlin-Anhalt Railway Company . Connections to Leipzig, Halle and Wittenberg were established just two years later . Bitterfeld thus became a railway junction in 1859 and had an excellent starting point for the development of the local lignite and stoneware industry. The railway network was supplemented in 1897 with the Bitterfeld – Stumsdorf line , which connected the Bitterfeld railway junction directly with the Magdeburg –Halle line .

In 1868 the Kreischaussee Bitterfeld- Zörbig was opened. In 1906 a commission was set up to prepare the construction of a railway line from Bitterfeld to Eilenburg . However, due to the First World War , which broke out a little later , the plans for this were rejected again.

Bitterfeld was a starting point for electric train traffic in Germany . In 1911, the German Reich's first electrified standard-gauge full-gauge line began operating between Bitterfeld and Dessau . With the nearby Muldenstein railway power station , the first railway's own power station to provide the required traction power was built in 1912 . With the beginning of the First World War, the electrical operation was stopped and only started again in 1922/1923.

The Reichsautobahn from Berlin to Nuremberg (today's A 9 ) touches the district and was opened in 1938. There are three driveways to the A 9 in the former Bitterfeld district : Dessau-Süd, Bitterfeld-Wolfen and Brehna. The federal highways 100 (Halle / Saale – Bitterfeld-Wolfen – Lutherstadt Wittenberg), 183 ( Köthen –Bitterfeld-Wolfen– Torgau - Bad Liebenwerda ) and 184 (Magdeburg– Zerbst –Dessau – Bitterfeld-Wolfen – Leipzig) run through the city .

The Bitterfeld station 's long-distance maintenance of Intercity Express -line Hamburg -Berlin-Halle-Erfurt- Munich . In regional traffic, there is an hourly Regional Express connection to Leipzig, Dessau and Magdeburg. Since December 2013, Bitterfeld has been connected to the network of the Central German S-Bahn . Bitterfeld is the transfer point for lines S2 and S8. There are 30-minute intervals to Halle and Leipzig on weekdays. There is a 60-minute cycle in the direction of Dessau and Lutherstadt Wittenberg, with lines S2 and S8 alternating in both directions.

The railway line to Stumsdorf is only served by freight traffic, local passenger traffic is provided by the Vetter Verkehrsbetriebe bus line 440 , via Sandersdorf and Zörbig .

Personalities

Sons and daughters of Bitterfeld

- Johann Ernst Altenburg (1734–1801), trumpeter and organist

- Adolf Hilmar von Leipziger (1825–1891), Upper President of West Prussia

- Emil Obst (born June 14, 1853, † January 24, 1929) has made an extraordinary contribution as a local researcher in the Bitterfeld region since 1876. His collection formed the basis of the city museum he founded in 1892. Until his death he worked tirelessly as a chronicler and homeland researcher, the local history of the present is based on his research results.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Thon (born April 25, 1859 - † May 7, 1932) Thon was a writer and published numerous works under the pseudonym Fritz Erdner. He studied German and classical languages. After receiving his doctorate in 1888, he came to Bitterfeld as a teacher. His extensive estate is now in the Bitterfeld City Archives.

- Arno Werner (1865–1955), teacher, organist and music historian

- Sella Hasse (1878–1963), painter and graphic artist

- Rolf Habild (1904–1970), district administrator in Bitterfeld from 1933 to 1945

- Hans Werner Schmidt (1904–1991) art historian, museum director in Braunschweig

- Erwin Ding-Schuler (1912–1945), SS-Sturmbannführer and first camp doctor at the Buchenwald concentration camp

- Adolf Drescher (1921–1967), pianist

- Franz Klepacz (1926–2017), football player

- Nikolaus Cybinski (* 1936), aphorist

- Lutz Zülicke (* 1936), theoretical chemist

- Gunter Herrmann (1938–2019), painter, graphic artist and restorer

- Joachim Müller (* 1938), historian

- Rudi Czaja (1939-2001), Member of the State Parliament (DVU)

- Hartmut Weule (* 1940), process engineer

- Hans Zimmermann (1948–2015), site manager, environmental activist (in June 1988 worked on the contrasts contribution Bitteres from Bitterfeld )

- C. Bernd Sucher (* 1949), theater critic and author

- Peter Rasym (* 1953), musician, has been playing bass guitar with the Puhdys since 1997

- Bettina Fortunato (* 1957), politician (left)

- Matthias Hermann (* 1958), writer

- Chris Böhm (* 1983), BMX athlete and freestyler, entertainer and record holder in the Guinness Book of World Records

- Jochen Seidel (1924–1971), painter and graphic artist

Other personalities

- August von Parseval (1861–1942): Some of the impact airships he developed were built in Bitterfeld. In 1907 an airship yard was established here. Parseval was an honorary member of the "Airship Association of Bitterfeld and Surroundings" founded in 1909. In 1910, the Parsevalstraße running there was named after him. The vocational school center, which was newly built between 1998 and 2000, is located on Parsevalstrasse . In the same year, the vocational school center was given the honorary name “August von Parseval” at a ceremony.

- Walther Rathenau (1867–1922): He brought the chemical industry to Bitterfeld by setting up the electrochemical works on behalf of the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft ( AEG ) in 1893, thus establishing the region's rise to an industrial center.

- Paul Othma (1905–1969): Electrician, spokesman for the strike committee of June 17, 1953, sentenced to 12 years in prison.

- Manfred Sult (1934–2016), Baptist pastor and from 1981 to 1991 President of the Federation of Evangelical Free Churches in the GDR

- Klaus Staeck (* 1938): graphic artist and lawyer as well as President of the Academy of Arts, grew up in Bitterfeld and lived here on June 17, 1953.

mayor

The city council consisted of the mayor and up to three council friends. They were all re-elected every year, so that each of them presided over the council at least once every three years.

- 1473 Dictus Poyde

- 1556 Moritz Poyda († 1560)

- from 1558 alternating: Moritz Poyda († 1560), Nicolaus (or Nickel) Harding († 1576), Hermannus Bartholdus († 1589), Hans Quale († 1593) and Wenzel Haynn († 1631)

- 1591, 1594, 1597 Conradus Reuter († 1626)

- 1596 Paul Reuter

Mayors from the 17th to the 18th century are not known except for one Valentin Becker, who died in 1661.

- 1727 to 1731 Johann Christoph Schildhauer (* 1666; † 1745)

- until 1816 Johann Christian Friedrich Schmiedt, Johann Gottfried Barth, Johann Gottlieb Ander

- 1831 to 1837 Friedrich Gottlieb Viole (* 1796; † 1837)

- 1837 to 1846 Johann Gottlieb Ullrich

- 1846 to 1848 Johann Friedrich Liepe (declared mentally ill)

- 1848 Franz Hellwig (election not accepted)

- 1848 to 1850 Heinrich August Atenstaedt († 1850) (interim)

- 1850 to 1851 Johann Friedrich Liepe (apparently recovered)

- 1851 to 1863 Gottlieb Meuche

- 1863 to 1873 Gustav Frischbier

- 1873 to 1890 Robert Sommer († June 18, 1890)

- 1890 to 1914 Hugo Hermann Adalbert Dippe (born June 3, 1853 - † June 4, 1916)

- 1915 to 1927 Ernst Albert Hermann Schmidt (election already 1914, postponed due to military service)

- 1927 to 1939 Arthur Erdmann Ebermann

- 1939 to 1945 Ehrhard Johann Martin Nimz

- 1943 to 1945 Walter Stieb (interim)

- April 26, 1945 to August 30, 1945 Gustav Dietrich (voted out by Soviet city commanders) († 1972)

- September 1945 to 1946 Bernhard Moder

- 1946 to 1949 Ernst Rettel

- 1949 to 1950 Karl Salbach

- 1950 to 1953 Heinz-Rudolf Strauch

- 1953 to 1959 Wolfgang Stille

- 1959 to 1971 Else Petruschka

- 1971 to 1979 Max Dittbrenner

- 1979 to 1982 Karlheinz Sohr

- 1982 to 1990 Klaus Barth

- 1990 to 1994 Edelgard purchase

- 1994 to 2007 Werner Rauball

Local mayor from 2007:

- 2007 to 2009 Horst Tischer

- from 2010 Joachim Gülland

Honorary citizen

- Eugen Gustav Goltz, city councilor, honorary citizen on January 2, 1896

- Heinrich August Piltz , city councilor and industrialist, honorary citizen in 1902

- Albert Richter, businessman and city councilor, honorary citizen in 1924

- Former Chancellor Adolf Hitler and former President Paul von Hindenburg (both in the 3rd Reich), honorary citizens in 1933 (both were revoked from honorary citizenship by resolution of the city council of Bitterfeld on August 16, 1990)

- Lothar Hentschel (born February 19, 1930 - January 18, 1999), mayor of the twin town of Marl, honorary citizen in 1996

- Ernst Thronicke (born September 6, 1920 - † October 28, 2007), drawing teacher and painter, honorary citizen 1998

Note: Honorary citizenship is a right that, according to Section 34 of the municipal code of Saxony-Anhalt, can only be granted to living persons. It goes out with death. The same also applied to the provincial constitution of the state of Saxony-Anhalt that was previously in force. For this reason, strictly speaking, Bitterfeld no longer has an honorary citizen.

Literature on Bitterfeld

- Bitterfeld and the lower Mulde valley (= values of the German homeland . Volume 66). 1st edition. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, ISBN 978-3-412-03803-8 .

- Ehrenfried Keil, Siegfried Kunze: Bitterfeld. When the chimneys were still smoking. Leipziger Verlagsgesellschaft, Publishing House for Cultural History and Art, Leipzig 2004.

- Peter Hoffmann: When Bitterfeld still had a beer. Association for Culture and Help in Life, 2000.

- City of Bitterfeld (Ed.): 775 years of Bitterfeld. Forays into the history of a city . Mitteldeutscher Verlag , Halle (Saale) 1999, ISBN 3-932776-79-8 .

- Peter Hoffmann : Bitterfeld. Mosaic of memories. Bitterfeld 1999.

- Chemie AG Bitterfeld-Wolfen (ed.), B. Tragsdorf, J. Marcy, G. Sandring, Chr. Angermann (red.): Bitterfeld Chronicle. 100 years of the Bitterfeld-Wolfen chemical site. Druckhaus Dresden, Dresden 1993.

- Roswitha Einenkel: 100 years of the Bitterfeld Museum, 1892–1992. Bitterfeld 1992.

- Monika Maron: Fly ash . (Roman) Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 978-3-596-23784-5 .

- Paul Grimm: On the development of the city of Bitterfeld and its corridor. Bitterfeld no year

- Werner Dietze: Chronicle of the city of Bitterfeld. no year (around 1935)

- Emil Obst: Guide through Bitterfeld and the surrounding area. Bitterfeld 1893.

Films about Bitterfeld

- Bitter from Bitterfeld , 30 minutes, article in the ARD magazine Kontraste from September 27, 1988 by Rainer Hällfritzsch, Ulrike Hemberger and Margit Miosga with the collaboration of Hans Zimmermann from Bitterfeld and Ulrich Neumann from East Berlin from the green-ecological network Arche environmental activist Hans Zimmermann recalls in an interview with Hellmuth Frauendorfer, mdr-Magazin Fakt (Magazin) | Fakt from April 12, 2010

- Documentary: That was Bitteres from Bitterfeld , 45 minutes, by Rainer Hällfritzsch, Ulrike Hemberger and Margit Miosga, WIM e. V. Berlin , in coproduction with the MDR , 2005 Background on the film (The film reconstructs how it was possible to make the recordings undetected, despite the presence of 18,000 Stasi employees in the region, to smuggle them to the West and there to be included as a magazine article in the ARD magazine Kontraste .)

Web links

- Website Bitterfeld

- Reports, documents and photos on jugendopposition.de : Volksaufstand 1953 in Bitterfeld

- Portrait of the Bitterfeld strike leader Paul Othma

- Ralf Herzig: Bitterfeld - description of a sadness. A photo essay , in: Horch and Guck , 18th year, issue 64 (2/2009), pp. 12-13.

swell

- ^ German Weather Service, normal period 1961–1990

- ↑ Mitteldeutsche Zeitung: Bitterfeld, one name, many stories

- ↑ Matthäus Merian: Topographia Superioris Saxoniae, Thüringiae, Misniae et Lusatiae (Upper Saxony, Thuringia, Meißen and Lausitz) 1650, page 31. Restricted preview in the Google book search

- ^ Karlheinz Blaschke , Uwe Ulrich Jäschke : Kursächsischer Ämteratlas. Leipzig 2009, ISBN 978-3-937386-14-0 ; P. 22 f.

- ↑ Monika Maron: Fly ash . Novel. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 978-3-596-23784-5 .

- ↑ Ralf Herzig: Bitterfeld - Description of a sadness. A photo essay. in: Horch and Guck , Volume 18, Issue 64 (2/2009), pp. 12-13. Article on the net ( Memento of September 27, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Reports, documents and photos on the 1953 popular uprising in Bitterfeld on jugendopposition.de ( Federal Agency for Civic Education / Robert Havemann Society ), viewed on March 20, 2017.

- ^ Telegram to the government of the GDR on jugendopposition.de ( Federal Agency for Civic Education / Robert Havemann Society ), viewed on March 20, 2017.

- ↑ 1953 popular uprising in Bitterfeld, photos and texts on jugendopposition.de ( Federal Center for Civic Education / Robert Havemann Society eV), viewed on March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Kulturpalast Bitterfeld (see: House with Tradition 1952–2002)

- ↑ July 11, 1968. The big bang from Bitterfeld. In: Jan Eik and Klaus Behling: classified. The greatest secrets of the GDR. Verlag Das Neue Berlin, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-360-01944-8 , pp. 116–117

- ↑ The vernacular said that films could be developed in this lake, but this was not the case, since mainly remnants of synthetic fiber production were initiated. Cf. Ralf Herzig: Bitterfeld - description of a sadness. A photo essay. In: Horch und Guck , Volume 18, Issue 64 (2/2009), pp. 12-13. Article on the net ( Memento of September 27, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The environmental activist Hans Zimmermann from Bitterfeld recalls in conversation with Hellmuth Frauendorfer. In: fact . April 12, 2010, archived from the original on April 17, 2010 ; Retrieved January 5, 2015 .

- ^ StBA: Changes in the municipalities in Germany, see 2007

- ↑ Martin Cassel-Gintz, Dorothee Harenberg: Syndrome of Global Change as an Approach to Interdisciplinary Learning in Secondary School A manual with basic and background material for teachers. 2002, p. 54.

- ↑ Scientific Advisory Council of the Federal Government on Global Change (WBGU): World in Transition: The Endangerment of Soils . Annual report 1994. Economica Verlag, Bonn 1994, ISBN 3-87081-334-2 ( online (PDF; 5.7 MB) [accessed on November 22, 2012]). online ( Memento from May 21, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Saxony-Anhalt State Statistical Office: Election of the 7th State Parliament of Saxony-Anhalt on March 13, 2016 ( Memento of March 14, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ https://www.mdr.de/sachsen-anhalt/dessau/bitterfeld/wahrzeichen-kulturpalast-zukunft-veranstaltungszentrum-100.html

- ↑ Portrait of the Bitterfeld strike leader Paul Othma

- ↑ The mystery of the management responsible for the Solibro insolvency is expanding. November 5, 2019, accessed November 6, 2019 .

- ↑ South Korean company takes over Q-Cells. In: time. August 29, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012 .

- ↑ Sovello solar company fires all employees. In: FAZ. August 21, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012 .

- ↑ Companies at the location on the website of PD ChemiePark Bitterfeld Wolfen GmbH

- ^ Yearbook for Eilenburg and the surrounding area 2006

- ↑ Wolfgang Beuche: The industrial history of Eilenburg Part I, 1803-1950 , 2008, ISBN 978-3-8370-5843-7

- ↑ Motorway openings 1938 In: autobahn-online.de

- ↑ Paul Othma tries to curb violence and tries to enforce the strike committee as the new power center on jugendopposition.de ( Federal Center for Political Education / Robert Havemann Society eV), viewed on March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Short biography of Paul Othma

- ^ Eyewitness report by Klaus Staeck on the 1953 popular uprising in Bitterfeld on jugendopposition.de ( Federal Center for Civic Education / Robert Havemann Society eV), viewed on March 20, 2017.