Ministry of State Security

The Ministry of State Security ( Stasi ), including the State Security Service , known by the acronym Stasi , was in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) at the same time intelligence and secret police and acted as a government instrument of the Socialist Unity Party (SED). Formally, it was a " Ministry of the Armed Organs" within the Council of Ministers of the German Democratic Republic . The main administration of intelligence (HVA), the foreign secret service of the GDR, was one of about twenty main administrations of the MfS.

The MfS was founded on February 8, 1950 and developed into a widespread, well-staffed surveillance and repression apparatus , which in 1989 had around 91,000 full-time employees and between 110,000 ( Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk ) and 189,000 ( Helmut Müller-Enbergs ) unofficial employees ( IM) belonged to. Müller-Enbergs identified primarily political ideals as motives for the cooperation. Money only played a subordinate role, and extorted cooperation with the GDR informers was rare. Domestically, the MfS used as an instrument of power had a protective function for state organs and people.

People from the GDR were targeted by the Stasi when there was suspicion of political resistance to the SED, espionage or flight from the republic . Methodically, the MfS used observation , intimidation , imprisonment and the so-called disintegration against opposition and regime critics (“ hostile-negative persons ”) as means. In the 1950s, physical torture was still used in the Stasi prisons , and later sophisticated psychological methods were used. In the 1980s, the Stasi repeatedly trained terrorists of the Red Army Faction (RAF) in the use of weapons and explosives.

In the course of the peaceful revolution in autumn, the MfS was renamed the Office for National Security (AfNS) in November 1989 , which ceased its activities at the beginning of December as a result of pressure from the citizens' committee and was completely dissolved by March 1990. The Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the Former German Democratic Republic (BStU) has been responsible for researching and managing the written legacy of the authority . The MfS is the only secret service in German history that has been comprehensively uncovered and processed.

With the Feliks Dzierzynski guard regiment , the MfS also had its own military-operational force, which in 1990 comprised around 11,000 men. In addition to the MfS, there was another intelligence service in the GDR, the military reconnaissance of the National People's Army , based in Berlin-Köpenick . Like the border troops and the rest of the NVA, this was controlled by Main Department I (MfS Military Defense or Administration 2000 ) of the MfS.

history

precursor

When it was founded on February 8, 1950, the Ministry of State Security built on two predecessor organizations with Soviet characteristics. The Interior Ministry of the USSR (before 1946 NKVD, a "People's Commissariat", renamed as Ministry from 1946 to MWD) and the then Soviet "Ministry for State Security" KGB (1941–1946 NKGB, 1946–1954 MGB, from 1954 KGB) installed under Lavrenti Beria established a number of independent, extensive intelligence and police active units in the Soviet zone of occupation . Its head was initially the Soviet Colonel General Ivan A. Serow , from 1946 Nikolai K. Kovalchuk .

The Communist Party of Germany had soon after the arrival of the Moscow KPD cadres a "party political department" and a "border Apparatus / transport" established that an intelligence service equaled. In August 1946, the SED, which emerged from the forced unification of the SPD and KPD , founded the "German Administration of the Interior" (DVdI), which was initially headed by Erich Reschke , and from 1948 by the former Soviet military espionage agent Kurt Fischer . The DVdI had a "K5 Unit" for the so-called "Kriminalpolizei 5", or K5 for short. K5 departments were responsible for “class V offenses” (“offenses of another kind”) on site. At the state level, the K5 departments carried out intelligence operations and tasks; they were part of the political police . They had been set up, among other things, by the occupying power required rapid denazification drive by in the Soviet zone of occupation former Nazi officials detected and the judiciary for quick trial was delivered to. From the beginning, employees of the K5 also performed other tasks in accordance with Control Council Act No. 10 (K5c), such as the processing of "attacks on public figures " (K5c1), " sabotage on construction" (K5c2), the fight against "spread of anti-democratic agitation slogans and rumors "(K5c3)," Monitoring of radio and telephone devices "(K5c4) and" other violations of the democratic structure "(K5d1 and K5d2), and thus an overall supervision of the German police, the administration, the Justice and the awakening public life in trade unions , schools and churches, etc. From 1948 onwards, the DVdI's K5 unit standardized the criminal police, which had previously been organized on a federal level , and the associated K5 also at the level of the state criminal investigation offices and police officers 5 of the local police stations. After Walter Ulbricht's interview with Josef Stalin, the K5 became an independent body with his consent and became known as the main administration for the protection of the national economy when the GDR was founded in 1949 . The workforce of the head office for the protection of the national economy rose rapidly from 160 employees in 1946 to 700 employees in April 1948.

Foundation and development

In the 1950s, the Stasi was able to establish itself as the Stalinist secret police and in 1956 already had around 16,000 employees. The basis for the establishment of an independent secret police was laid by the Politburo of the CPSU on December 28, 1948 with the decision to form the "Central Administration for the Protection of the National Economy". With this decision, Walter Ulbricht , Wilhelm Pieck and Otto Grotewohl were able to assert themselves against the fears of the Soviet Minister for State Security, Viktor Abakumow , who was concerned about the effect of this decision on the Western Allies .

On January 24, 1950, the Politburo of the SED passed the resolution to form the MfS. Two days later, the government of the GDR recommended the formation of the MfS in parallel to its own “resolution to ward off sabotage” . On February 8, 1950, the People's Chamber of the GDR unanimously approved the law on the formation of a Ministry for State Security , which came into force on February 21, 1950. Control of the newly created ministry by parliament or the Council of Ministers was not provided for in the law. Wilhelm Zaisser was appointed director on February 16, 1950 . Erich Mielke was his deputy in the rank of State Secretary . By the end of the year, the newly founded ministry had around 2,700 employees.

In the course of the administrative reform of 1952 , the five MfS regional administrations (LV) were dissolved and 14 district administrations (BV) were set up instead. The property management company Wismut (Department "W"), founded in 1951, remained. Furthermore, the construction of a network of initially 192, later 216 object and district offices (KD) was planned. The German border police and the transport police were subordinated to the Ministry for State Security. The administrative reform and the "intensification of the class struggle " led to a doubling of the apparatus from 4,500 (end of 1951) to around 8,800 employees (end of 1952).

Popular uprising of June 17, 1953

After the MfS "failed" in the early detection and suppression of the so-called "rioting" of the popular uprising on June 17, 1953, from the point of view of the Politburo, the Ministry was downgraded to the " State Secretariat for State Security (SfS)" on July 23, 1953 and the Ministry of the interior of the GDR under Willi Stoph ; It was not until November 24, 1955 that it was given ministry status again and was assigned to the foreign intelligence service called the Main Administration of Enlightenment . The measure, however, was also an adaptation to Soviet structures, which Lavrenti Beria had also initiated as a tactical gesture to the West. In the course of the power struggles that took place shortly afterwards, Minister for State Security Wilhelm Zaisser , who had been in office since February 8, 1950, was removed from his ministerial post for "anti-party factional activity", expelled from the SED Central Committee and one year later from the SED. The Deputy Minister Erich Mielke also had to undergo a review of his administration, but was allowed to keep his post. Ernst Wollweber became head of the SfS and then Minister of the MfS .

However, the MfS played an important role in the investigation and arrest of the so-called “ ringleaders ” and “western provocateurs ”. By the evening of June 22, 1953, more than 6,000 people were arrested by the MfS and the People's Police .

Throughout the 1950s, in numerous political purges, party members were arrested who had emigrated to western countries during the Nazi era ; Other SED members were also victims of these actions. Kurt Müller , Willi Kreikemeyer , Paul Merker , Max Fechner , Karl Hamann and Georg Dertinger were among the most prominent victims of the Stalinist party purges in the GDR . In addition, during this time the MfS kidnapped around 600 to 700 people from the West into the GDR in the course of various arrests against “enemy agents”.

A brief phase of de-Stalinization led to the early release of 25,000 prisoners in the summer of 1956, including many political prisoners. The torture practice that had been common up to that point was also discussed internally. But already after the popular uprising in Hungary in 1956 , another wave of repression followed , which also fell victim to prominent communists, Wolfgang Harich and Walter Janka . Wollweber also got into open conflict with Walter Ulbricht . On his order, Wollweber was replaced by his deputy Mielke in 1957. This led the Stasi until November 7, 1989, the day the resignation of Ministers of the GDR to turn .

The MfS after the Wall was built in 1961

The internal unrest in Poland and Hungary as well as the critical statements by the intellectuals led to a renewed change of course within the MfS - the focus was increasingly on repression against internal oppositional forces. This was reflected in the “ Doctrine of Political-Ideological Diversion ” (PID), which traced all forms of internal opposition back to the influence of the “ imperialist enemy” and at the same time established the growing presence of state security in all areas of everyday life. This was favored by the construction of the wall , which prevented opposition members from moving away. If the main tasks of the MfS before the building of the Wall were to fight Western secret services and the escape movement, the MfS should in future increasingly identify potential sources of unrest as a preventive measure. The Prague Spring proved to be the first practical test for the realigned apparatus .

In May 1971 Walter Ulbricht was overthrown by Erich Honecker . In the course of this, the Minister for State Security Erich Mielke was initially elected as a candidate and five years later as a member of the Politburo with voting rights. However, both of them discussed key issues relating to the work of the MfS in weekly one-on-one discussions. Since the early 1970s, the GDR was increasingly concerned with international recognition and German-German rapprochement . This also led to changes in the methods of state security. Since the GDR had declared its intention to respect human rights both in the basic treaty with the Federal Republic of Germany and by joining the UN Charter and signing the CSCE Final Act , the MfS increasingly tried to sanction oppositional behavior without applying criminal law and instead tried to do so To resort to “soft” and “quiet” forms of repression - such as disruptive measures. This required systematic and comprehensive monitoring with the use of up to 200,000 unofficial employees . Through criminal prosecution, foreign and technology espionage, as a mood barometer, censorship authority , to circumvent trade embargoes or to obtain foreign currency through prison labor and the release of prisoners , the MfS achieved a key function in the ruling system of the GDR.

Dissolution of the MfS

According to the plans of the SED, the MfS should be reformed. But developments overtook this. On November 18, 1989, the People's Chamber of the GDR set up the Modrow government , with the MfS being renamed the Office for National Security (AfNS). She appointed Wolfgang Schwanitz , deputy to the deposed Minister Mielke, to be the “head” . A downsizing of the apparatus was planned with the conversion.

However, that did not happen. 17 days later, on the morning of December 4, 1989, the district office of the AfNS in Erfurt was occupied by citizens after it became known that the Stasi files were to be destroyed. District offices in Leipzig , Suhl and Rostock followed on the evening of the same day . Occupations in the other district cities and most recently on January 15, 1990 in the Berlin headquarters followed. With the establishment of vigilante guards and citizen committees , the forced dissolution of the AfNS and the processing of the activities of the MfS began. Less than a month after the establishment of the Office for National Security, the GDR Council of Ministers under Hans Modrow tried again on December 14, 1989, to establish state security, obviously based on the intelligence service structures in the Federal Republic of Germany, through a constitutional protection agency with only around 10,000 employees and one Replace intelligence service . However, this did not happen because of the citizens' protests. On January 15, 1990, the round table urged the state security to end quickly. Citizens committee members from all over the GDR forced a security partnership and demonstrators stormed the grounds. During the night, a citizens' committee was formed to oversee the dissolution process.

MfS early 1990

On February 23, 1990, the Round Table approved the self-dissolution of the MfS's foreign intelligence , the so-called Headquarters Enlightenment , HV A. After two weeks of discussion, it was decided on February 26th to destroy almost all files and data carriers of the AGM. Nonetheless, the mob ( mobilization ) files came into the hands of the CIA under unexplained circumstances in 1990 . They were later known under the name " Rosewood Files " and copied to the federal government in 2003. As of March 31, 1990, all Stasi employees had been dismissed except for a few hundred who had received fixed-term employment contracts in order to continue winding up the institution . Finally, on May 16, 1990, the Council of Ministers recommended forming a special committee “Dissolution of the MfS”, which one and a half years later became the authority of the Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former GDR .

Fiduciary management of the MfS's assets

After the self-dissolution (of the MfS) and the reunification of Germany, the assets of the MfS were subject to the trust administration by the Treuhandanstalt and the Independent Commission for the Review of the Assets of the Parties and Mass Organizations of the GDR (UKPV) according to the Treuhandgesetz .

Legal and social processing

Stasi Records Act

The dissolution of the State Security did not end with the reunification on October 3, 1990. On December 29, 1991, the Stasi Records Act (StUG) came into force, which the German Bundestag had passed with a large majority. The central concern of this law is the complete opening up of the files of the former State Security Service, in particular the access of those concerned to the information that the State Security Service has stored about them. For the first time, citizens were given the opportunity to inspect documents that a secret service had created about them. This was ensured by the specially established office of the Federal Commissioner for the Documents of the State Security Service of the former GDR , often called Gauck , later Birthler and Jahn authority for short after the heads .

According to the provisions of the Stasi Records Act, the naming of IM is permitted for the purpose of clarification and research. In March 2008, Holm Singer ("IM Schubert") obtained an injunction against the exhibition "Christian Action in the GDR" organized by Edmund Käbisch at the Zwickau Regional Court . The exhibition was then temporarily canceled. The legal dispute was ended by the Zwickau Regional Court on March 24, 2010 by default judgment : "It is ... not objectionable that the MfS's approach is personalized to the individual case, and the actions of the defendant (Holm Singer) by the plaintiff (Edmund Kaebisch) is specified with full attribution. In particular, the concretization made on the basis of individual fates is known to make it easier for historical laypeople to familiarize themselves with otherwise difficult-to-understand historical topics ... The concretizing representation enables the full extent of the involvement of the MfS to be made clear and to show on the basis of an individual fate how the MfS was able to infiltrate and manipulate even relatively closed oppositional circles ... ”.

Rehabilitation of victims

The Criminal Rehabilitation Act , which came into force in 1992, regulates the repeal of grossly illegal penal measures and deprivation of liberty. Compensation payments are linked to the criminal rehabilitation . In the opinion of the victims' associations , the rehabilitation legislation only incompletely covers the losses that Stasi victims had to suffer. B. illegal imprisonment or an occupational ban are not taken into account in the pension calculation. Those affected today have to live below the poverty line , while former employees of the Ministry for State Security receive a pension for their work in the Stasi regime.

Historical revisionism by former Stasi cadres

Former Stasi cadres still practice historical revisionism decades after the secret service was dissolved , glorifying and making the SED dictatorship beautiful and trying to defame the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen memorial and earlier victims .

In April 2006, Marianne Birthler , then Federal Commissioner for the State Security Service's records , stated that former full-time employees of the MfS, now organized in associations, tried to “improve the reputation of the GDR in general, and the Stasi in particular, to lie around the facts”. They also draw from the fact that there were only around 20 convictions in 30,000 preliminary proceedings against MfS employees, the cynical conclusion that “it couldn't have been that bad”. There were hardly any convictions because in a constitutional state only acts that violated the law at the time they were committed ( prohibition of retroactive effects, nulla poena sine lege ) can be punished . So if there was no violation of GDR laws at the time of the crime , it cannot be sentenced for this today. Only in the case of serious crimes and homicides that are not treated as criminal offenses, such as the execution of the order to shoot , would the principle apply that the unlawful laws of dictatorships cannot apply ( Radbruch's formula ). Unfortunately, it is a fact that unlawful acts by the MfS against prisoners or people under surveillance who were victims of the MfS 'methods of decomposition cannot lead to convictions. "But to conclude from this that this is not an injustice, that is the height of cynicism ."

Memorials

The Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial now exists in the premises of the former central remand prison of the Stasi, in which from 1951 to 1989 mainly political prisoners were physically and mentally tortured . The research and memorial site Normannenstrasse is located in the main building of the Stasi in Berlin . The museum memorial in the “Runden Ecke” is a Stasi museum in Leipzig. There is also the Bautzner Strasse Dresden Memorial . The Bautzen Memorial dedicates a thematic focus to the Stasi Special Detention Center Bautzen II (1956 to 1989).

assignment

The MfS was mainly the secret police of the GDR, which acted as a surveillance and repression body of the SED without parliamentary and administrative judicial control and controlled the GDR society in all areas. The MfS can only be seen as a foreign intelligence service in the second place.

The main task was reflected in the numerical distribution of the staff. Under the direction of the Stasi , a total of 33,000 political prisoners were deported from the GDR to West Germany in the years 1964 to 1989 in the prisoner ransom transactions, for a per capita payment of between DM 40,000 and DM 95,000.

The methods included partly under torture forced confessions and theatrically staged show trials including the preparation of their judgments.

By resolution of the SED Politburo of September 23, 1953, it was determined that the Ministry of State Security, as a military body, should operate both as a domestic and foreign intelligence service. This included the following areas of responsibility:

inland

- Execution of agent activities, e.g. B. Control of mass organizations and targeted dismantling and splitting of potential oppositional circles, such as intellectuals, dissidents , as well as the church and its youth groups.

- Comprehensive surveillance of GDR citizens and some of their relatives outside the GDR, disregarding their civil rights . In the jargon it was also called "detection and elimination of hostile decomposition activities". This was done, among other things, by spying on, censoring the press and films, and suppressing freedom of expression .

- Investigation and pre-trial detention in the case of criminal offenses such as flight from the republic in accordance with Section 213 of the GDR Criminal Code (referred to there from 1968 as “ illegal border crossing ”) and anti-state agitation .

- Control ("protection") of all armed organs of the GDR (border troops, NVA and people's police)

- Control ("protection") of the state apparatus (other ministries)

- Control ("safeguarding") of the economic organs ( combines and companies)

- Control ("safeguarding") of traffic and tourism

- Cooperation between security organs and the People's Police

- Personal protection of party and state officials

- Monitoring of so-called "privileged persons" ( diplomats , accredited press and business people)

After deaths at the Berlin Wall or the inner-German border, the MfS took over the investigation and concealment of the events from the public and relatives. The MfS “legend” the cases in order to either give them little or no attention or to direct attention in a certain direction. The MfS stylized killed border guards into heroes, for whose death enemy agents or criminals are responsible. Crime scene investigation reports, death certificates and other documents were forged for this. The MfS also checked the whereabouts of the bodies and the circumstances of the funeral. Relatives were obliged to keep silent about the circumstances of death or were told fabricated stories. In 1975 Mielke described his ministry as a “special organ of the dictatorship of the proletariat ”.

foreign countries

- Carrying out covert operations typical of the secret service (MfS term: active measures ) and espionage by the head office of investigation (HV A)

- Educational work in West Germany and West Berlin with the aim of gaining information from all important institutions of the Western Allies ( Bonn government, industry, research).

- Active counter-espionage and defense against attacks by private and state organizations

- Active influencing of public life in the West through intrusion of MfS informants into all important areas (for example through active disinformation )

- In the context of foreign missions of the NVA , for example in Mozambique , due to the possible risk of flight, “civilian missions” for construction projects and infrastructure were carried out with forces (among others from the Feliks Dzierzynski guard regiment ) who did not appear in uniform.

Assassinations

Various assassinations by the MfS on opponents of the regime living in the west are documented. After the Wall was built in 1961, the Stasi trained “fighters” who practiced liquidating people on a secret military training area . MfS agents tried several times to murder the escape helper Wolfgang Welsch , who lived in the Federal Republic of Germany . In the murder of the East German dissident Bernd Moldenhauer , who lived in the West, there was evidence that the MfS had commissioned the perpetrator. Siegfried Schulze, who fled the GDR in 1972 and took spectacular actions against the Berlin Wall, was the target of an assassination attempt in 1975. It was suspected that the MfS was involved in the accidental death of the soccer player Lutz Eigendorf . Accordingly, Eigendorf was first injected with alcohol and then blinded while driving. A former IM with multiple criminal records also stated that he had received an order to murder Eigendorf from the MfS, but had not carried it out. However, the public prosecutor sees no objective evidence of third-party negligence in Eigendorf's death. A letter bomb attack was carried out on the escape helper Kay Mierendorff from Steglitz in 1982, which he survived with serious injuries; his wife died of the long-term consequences. "Mierendorff's right hand was half torn, both eardrums were destroyed (hearing loss), the right eye came out of the cavity, the face was covered with wounds, the abdominal wall and liver torn open, the intestine injured and deep tears in the upper arm and chest." several Stasi attacks foiled, but afterwards “Germany got too hot” for him and he moved to Florida. Assassinations on Rainer Hildebrandt and the Friedrichshain pastor Rainer Eppelmann were planned. The refugee border soldier Rudi Thurow was supposed to be killed in 1963 with a 1000 gram hammer. The defector Werner Stiller was supposed to be kidnapped or murdered in the GDR. The writer, civil rights activist and representative of the opposition in the GDR Jürgen Fuchs and his surroundings were terrorized with numerous " Stasi dismantling measures " because he openly reported about the Stasi and the release of prisoners . Assassinations followed. In 1986 a bomb exploded in front of Fuchs' house and his car brakes were sabotaged.

Assassinations were planned in close coordination with the Soviet secret service KGB , the murder scenarios were personally approved by Erich Mielke. The victims included defectors from within their own ranks, above all from the SED apparatus, the People's Police and the National People's Army, as well as German citizens who were involved in anti-communist organizations.

terrorist attacks

Under the code name “Separat”, the Stasi had been in close contact with the terrorist group of the Venezuelan terrorist Carlos since at least 1980 . It has been proven that the GDR State Security Service was involved in international terrorism through the left-wing extremist terrorist group Revolutionary Cells :

- On August 25, 1983, a bomb attack was carried out on the Maison de France cultural center on Berlin's Kurfürstendamm . One person was killed and 23 seriously injured. The 24 kilograms of explosives destroyed the two top floors of the house, where the French consulate general that was attacked was located. In September 1990, the Federal Criminal Police Office in the Central Criminal Police Office in East Berlin came across a file that revealed the terrorist entanglements of the Ministry for State Security : The Stasi had enabled the German terrorist Johannes Weinrich , the head of the terrorist group Revolutionary Cells, to carry out the terrorist attack to prepare from East Berlin: Weinrich, traveling with a Syrian passport, brought the explosives to East Berlin in 1982, where the Stasi temporarily confiscated it . When Stasi employees were searched during a search of Weinrich's hotel room in January 1983 and gained insight into his plans for the planned bomb attack in Berlin, with which the terrorist Magdalena Kopp was to be freed from French custody, he received his 24 kg of explosives back. Because of this, Weinrich, who was also a member of the Organization of Internationalist Revolutionaries ("Carlos Group") and was considered the "right hand man" of the top terrorist Carlos, was sentenced to life imprisonment in the 1990s. The responsible former Stasi Lieutenant Colonel Helmut Voigt , at the time head of Department XXII (the Stasi counter- terrorism), was sentenced to four years imprisonment in 1994 for aiding and abetting murder.

- According to research by the SED-Staat research association , the MfS was actively involved in the bomb attack on the La Belle discotheque in Berlin-Schöneberg on the night of April 4th and 5th, 1986. The processed Stasi documents show that an unofficial employee of the Stasi was involved in the preparations for the nail bomb attack on the La Belle discotheque in Berlin, which was mainly visited by soldiers of the US armed forces on April 5, in which three people were involved died and suffered hundreds of injuries. The Stasi spy Yasser C., a Palestinian student from the Technical University of Berlin with the code name Alba, has scouted out three possible targets, including La Belle. A call girl with connections to the Stasi, Verena C., placed the bomb at the scene of the attack.

Support for right-wing extremists

According to the federal prosecutor's office, the Stasi helped West German right-wing extremists to flee underground , to the GDR. For example, the neo-Nazi Odfried Hepp (who had carried out several terrorist attacks and bank robberies in Germany with a right-wing terrorist group in 1982 ) was helped to dive into the GDR. The Stasi also helped the German right-wing extremist and arms dealer Udo Albrecht to flee the Federal Republic. Both became employees of the GDR State Security.

organization

In terms of population, the MfS was the largest secret police security apparatus in human history. The MfS staff consisted exclusively of full-time employees. The MfS began in 1950 with around 2,700 employees and ended in October 1989 with over 91,000 full-time employees (around 10,000 of them in international espionage). The full-time employees included career officers and NCOs, NCOs and temporary soldiers in military service, “ Officers in Special Use ” (OibE), “Full- Time Unofficial Employees” (HIM) and a small number of civilian employees. In addition, the Stasi apparatus maintained an army of around 200,000 secret informers, the unofficial employees (IM), who worked on their own initiative and at the same time had to submit to all the instructions of their full-time command officers. In the parlance of the SED, the MfS was referred to as the “shield and sword of the party”.

Recruiting full-time and unofficial employees

Independent applications from citizens were ignored. The MfS always selected its full-time employees individually and addressed the candidates in a targeted manner. In advance, each candidate was subjected to a strict examination and all first-degree relatives were thoroughly screened, which was intended to prevent hostile infiltration . The most important selection criterion for full-time employees was political reliability. Obedient socialist personalities with a clear class point of view were preferred , that is, what all political education in the GDR school system worked towards. Children of Stasi employees were given preference. In the case of forced or voluntary entry into the employment relationship, every employee had to take an oath on the flag of the GDR and the official flag of the MfS, the oath of the flag . In addition, a multi-page declaration of commitment had to be signed, threatening severe penalties - up to the death penalty - in the event of a breach of duty . You usually remained a Stasi employee until you retired. However, the retirement age of full-time employees was mostly far below the official retirement age in the GDR.

The recruitment of unofficial employees (IM) was called "advertising" in Stasi jargon. An "IM-leading employee" or a "management officer" was responsible for the promotion and subsequent management of an IM. As soon as the Stasi required additional information from a certain area, all persons working in this area were read out conspiratorially and "IM preliminary files" were created by suitable citizens. Potential IM candidates were then screened conspiratorially. This included the inspection of the school cadre files, the questioning of the teaching staff and other persons active in education, the review of social activities ( FDJ and GST ), the complete spying on the entire dealings of the aspirant, up to the questioning of the neighborhood by a section plenipotentiary of the People's Police . Then the liaison officer initiated one or more "contact meetings". Anyone who brushed off recruitment attempts or ended their spying activities had to reckon with professional and social disadvantages. Stasi candidates were baited with larger apartments, car purchases without the 15-year delivery time, groceries or technical consumer goods from the West that did not exist in the GDR's shortage economy . Sometimes attempts were made to force advertising with compromising information. If a candidate was hired as an IM, he was allowed to choose one of the secrecy serving aliases with which he had to sign his future spy reports.

Full-time employees

The full-time Stasi apparatus has built up a huge workforce over the decades. While the MfS predecessor, Administration for the Protection of the National Economy, had 1150 permanent employees in 1949, this number rose to 91,015 full-time MfS employees (including 13,073 regular soldiers) by October 31, 1989. During its existence, the MfS employed around 250,000 people full-time, including around 100,000 regular soldiers (including from the Feliks Dzierzynski guard regiment ). Almost 85 percent of the full-time MfS employees were men. Women mostly worked as typists, in the canteen, in the post office of Department M or as nurses in the medical field. Only a few management positions were held by women in the MfS; women only worked as operational employees in exceptional cases. The full-time employees saw themselves as an elite , who, in the tradition of the Soviet Russian secret police Cheka , should defend the GDR relentlessly and with hatred against its enemies.

With regard to the number of inhabitants, it is assumed that the MfS, with a quota of one full-time employee per 180 inhabitants (status: 1989), was the "largest secret police and secret service apparatus in world history" (for comparison: In the Soviet Union in 1990 a KGB- Employees per 595 inhabitants). The full-time Stasi employees spied on one another and, paradoxically, were the best-monitored group of people in the GDR. About 90% of all Stasi employees were members of the SED.

According to the employment guidelines of the Stasi, the employment of former Wehrmacht officers , NSDAP and SS members, as well as members of the police and secret service apparatus of the NS state was not permitted.

Unofficial employees

There was also a network of so-called unofficial employees (IM). In contrast to the case of full-time employees, the total number of unofficial employees was not subject to a continuous increase, but rose sharply in the context of internal social crises (June 17th, construction of the wall, German-German détente). In the years 1975 to 1977 the IM network reached its greatest expansion with over 200,000 employees. The introduction of a changed IM guideline with the aim of further professionalization led to a slight decrease in the number of 173,081 unofficial employees at the end of the 1970s (as of December 31, 1988, excluding HV A). In his book Stasi, Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk comes to the conclusion that this number is too high and that only 109,000 IMs were recently active. The different numbers result from different views on which groups of people are to be classified as unofficial employees and which are not. In the course of its existence, the MfS managed around 624,000 people as unofficial employees.

The majority of the unofficial employees worked in Germany. Agents who were on duty in the non-socialist economic area (NSW) were officially called scouts of peace . Only individual data is available on the scope of the IM network abroad. It is estimated that the MfS (including the HV A) recently employed around 3,000 unofficial employees in the "operational area" of the Federal Republic and 300 to 400 IMs in western countries. According to Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk, however, there were only about 2000 employees in Germany. Overall, the number of German citizens who have been in the service of the MfS in the course of its existence is estimated at around 12,000. In terms of quantity, they only made up less than two percent of the IMs of the MfS.

An entry as an IM is initially only to be regarded as an indication of a secret service activity: It cannot always be ruled out with certainty that mere contacts made by the MfS are documented as an IM in a file. It is not always possible to determine with certainty how close a person was to the MfS from notes and other entries on index cards alone; they only provide clues. The events can often only be comprehensively understood using the networked files. Unofficial activities can be proven if clear assignments are anchored in the MfS system. The F-16 and F-22 files that have been preserved offer the document security required by the Stasi Records Act in connection with file finds and personal (not absolutely necessary) declarations of commitment. Comprehensive documents are still preserved for some IMs, but destroyed for others. However, there are cross-references in other reports that can give a picture of what an IM is doing. The declaration of commitment to cooperate with the MfS can often no longer be found because a considerable number of files were destroyed before the ministry collapsed. In 2011, the BStU assumed that thousands of former western spies were still undiscovered.

Foreign agents

In the 40 years from 1949 to 1989, around 12,000 Western spies were active in the Federal Republic of Germany. At the time of the collapse of the GDR, there were around 2,000 active MfS spies in the Federal Republic of Germany, as the analysis of the so-called Rosenholz files published in March 2004 revealed. The number of IMs who worked for the intelligence headquarters in the GDR itself was put at 20,000. The MfS supported political forces in the Federal Republic of Germany which it considered useful. In West Berlin, the MfS tried in the early 1960s to control the emerging extra-parliamentary opposition (APO) by founding a party including the SEW - but this failed. Under the code name “ Gruppe Ralf Forster ”, the MfS trained selected DKP cadres in close combat and the use of explosives in the GDR . The MfS documents on the “Ralf Forster Group” were shredded and reconstructed in 2004 by the Birthler authorities. The agents of the MfS department for special warfare were supposed to prepare a military occupation of the "operational area" through diversion , espionage and sabotage. They were active in the Federal Republic and other western states, for example in Switzerland with the agent couple Müller-Huebner.

MfS and "Red Army Fraction"

In addition, employees of HA XXII repeatedly trained RAF terrorists in the handling of weapons and explosives in the 1980s . In connection with the assassination attempt on Frederick J. Kroesen , Christian Klar, Adelheid Schulz and Helmut Pohl received weapons lessons from Stasi people and practiced shooting with an RPG-7 bazooka. This paramilitary training and the weapons, foreign exchange and false papers provided by the Stasi made it easier for RAF terrorists to carry out attacks again in the early 1980s. On August 31, 1981, they exploded a car bomb at the headquarters of the United States Air Forces in Europe in Ramstein ( Ramstein Air Base ); seventeen people suffered injuries. On September 15, 1981 Klar fired a bazooka grenade at the vehicle of the Commander-in-Chief of the American Forces in Europe, General Frederick J. Kroesen. The shell hit the trunk of the armored vehicle; Kroesen was injured.

The MfS was also in contact with the Basque terrorist organization Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) and the IRA .

Eight terrorists from the Red Army Faction and two people from their environment found refuge in the GDR, protection from Western criminal prosecution and were given a legendary identity. They were monitored around the clock and settled separately from one another (no one knew the other's place of residence and new identity). According to Wolfgang Kraushaar's assessment, a Stasi planning paper from 1982 indicates the GDR's intention to use RAF terrorists specifically for killings, hostage-taking and bomb attacks in the Federal Republic. Erich Mielke considered using the RAF terrorists who had fled to the GDR as fighters “behind enemy lines” in an internal German conflict.

Control by the SED

In practice, all decisions concerning the MfS came from the Politburo , of which Erich Mielke was a member.

The only exception was the Central Committee for Security Issues (Security Commission), which was set up by the Politburo in 1953 to monitor the implementation of party congress resolutions in the “armed organs” and to guide the MfS in its political work. This security commission was responsible for approving all senior personnel decisions (promotions to colonel or higher). With this, the SED secured control over the key positions within the MfS. That meant that Mielke was also not completely without control within his ministry (there were certainly rejections of MfS personnel proposals).

Within the organization of the MfS, the heads of the district administrations were also members of the SED district leadership. The MfS was formally subordinate to the Council of Ministers of the GDR , but the instructions to the ministry came from the leadership of the SED and at the district level from the 2nd secretaries who were responsible for "agitation and security".

structure

Headquarters

The headquarters of the ministry in Berlin-Lichtenberg took up an entire block between Frankfurter Allee, Magdalenenstrasse, Normannenstrasse and Ruschestrasse. It consisted of 29 houses and 11 yards. The main access was via Ruschestraße. In addition, there was an additional building complex built later on Gotlindestraße. The office of the Minister for State Security Erich Mielke and his secretariat was in the main building (No. 1) with access from Ruschestrasse. In this building complex there were some main departments. The headquarters of the ministry also included a building complex in Berlin-Schöneweide, where some special departments were located. As a result of the upheaval in the GDR, the MfS headquarters was stormed by demonstrators on January 15, 1990 (entrance Ruschestrasse) and later taken over by civil rights activists already present in a security partnership. Since 1990 a museum and the research and memorial site Normannenstrasse have been located in the former building of the ministerial seat . In addition, the building is used by victim and processing groups such as the UOKG and the Citizens Committee 15. January eV. The building is a historical monument.

Territorial principle

The territorial instruction structure of the MfS corresponded to the administrative structure of the GDR in districts , districts and independent cities. Parallel to this, the MfS headquarters in Berlin-Lichtenberg (from July 1952) were subordinated to the MfS district administrations in each district town (until the administrative reform of 1952, MfS administrations of a similar structure existed in the individual countries). These were responsible for the subordinate departments in their territory as well as for selected objects, facilities and people. Operational processes and identity checks were processed in the regionally responsible district administration. In every district town or urban district there were also district offices that were controlled and instructed by the higher-level district administration. The district offices took responsibility for the territory of their respective seat. This territorial principle ensured that an MfS service unit was assigned to every location within the GDR.

Some object services were set up outside of the territorial structure to monitor particularly economically important companies (for example the object management "W" for the Wismut ).

Line principle

Internally, the MfS and its subordinate district administrations were divided into several structural units with technical content-related responsibilities (e.g. line II : counter-espionage; line IX: investigation; line XX: state apparatus, mass organizations, churches, culture and underground activities). Each of these "lines" had a main department based in the MfS headquarters in Berlin as well as corresponding departments or working groups in the district administrations. The main groups were usually numbered with Roman numerals . This line principle was no longer fully mapped at the circle level. Instead, depending on the regional importance of the area of responsibility, there were specialist units within the district offices or individual officers responsible for the area of responsibility.

- Minister for State Security

- Department 26 - Telephone surveillance and wiretapping , conspiratorial intrusion into objects

- Armament and Chemical Services Department (BCD)

- Finance department

- News Department - Ensuring the news system

- Department X - International Relations

- Department XI - ZCO, Central Encryption Organ of the GDR

- Department XIV - Central Prison Administration , securing the pretrial detention centers in Berlin-Hohenschönhausen and at the Minister's seat in Berlin-Lichtenberg , supervision of the remand centers of the 15 district administrations of the MfS

- Department XXIII - Counter Terrorism and Special Tasks, from 1989 integration into HA XXII, previously AGM / S , divided into combat, security and air traffic control escort command, as well as a specialized command with divers and parachutists

- Working group in the area of commercial coordination (AG BKK), responsible for the commercial coordination of Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski .

- Working group of the minister (AGM) - mobilization, protective structures

- Special units AGM / U

- AGM / S - "military-operational special tasks" (e.g. armed flight escort ) Central Specific Forces, was integrated into HA XXII in 1989, previously renamed to Department XXIII.

- Feliks Dzierzynski Guard Regiment

- Working group E with the Deputy Minister, Colonel General Mittig (AG E) - External security of military priority objects, development of technical means of defense against enemy automatic reconnaissance systems

- Working group XVII - Office for Visiting and Travel Matters (BfBR) in Berlin (West)

- Office of the management (BdL) - internal security of the MfS, courier service.

- Office of the Central Management of the Dynamo Sports Association

- Main Department I (HA I) - monitoring and securing the NVA , the military intelligence service and the border troops of the GDR (NVA-internal designation of HA I: Verwaltung 2000 or Büro 2000 ) In this area there was the highest penetration with IM (ratio one to five).

- Main Department II (HA II) - counter-espionage

- Main department III (HA III) - counter-espionage in the field of telecommunications and electronic reconnaissance (radio defense) , cross-border telephone surveillance

- Main Department VI (HA VI) - passport control , tourism (e.g. Interhotels ), security of transit and travel traffic (motorway service stations, transit parking lots, etc.)

- Main Department VII (HA VII) - "Defense" in the Ministry of the Interior (MdI) and the German People's Police (DVP)

- Department VIII (HA VIII) - observation, investigation. Securing transit road traffic , observation of military liaison missions (MVM). HA VIII was a cross-sectional department and was regularly requested by other HAs, with the exception of HA II and HVA, which had their own corresponding structural units.

- Main Department IX (HA IX) - Central Investigation Department, responsible for investigative proceedings in all cases of political importance. The HA had a direct influence on the course of the court hearings and the decision-making process. Minister Mielke underlined the importance of HA IX through his membership in its basic SED organization.

- Main Department XV - Former name of the main administration of the investigation before the spin-off, later as HVA-Dependance under the name of Department XV in the district administrations.

- Main Department XVIII (HA XVIII) - Securing the national economy, securing the facilities for arms research and arms production, control of the industrial, agricultural, finance and trade ministries as well as the customs administration of the GDR , clarification and confirmation of nomenclature cadres , foreign and travel cadres, military construction, HO-Spezialhandel with the GSSD as well as the foreign trade companies of the GDR

- Main department XIX (HA XIX) - traffic ( Interflug , Deutsche Reichsbahn and inland and maritime shipping), post and telecommunications, reconnaissance and confirmation of cadres

- Main Department XX (HA XX) - State Apparatus, Culture, Church, Underground. Ensuring military telecommunications technology and the Society for Sport and Technology (GST)

- Main Department XXII (HA XXII) - "Counter Terrorism"

- Main Department of Personal Protection (HA PS)

- Main Management and Training Department (HA KaSch)

- (Legal) university of the MfS

- Central Medical Service (ZMD)

- Operational-Technical Sector (OTS)

- Rear Services Management (VRD)

- Central Working Group on Secrecy Protection (ZAGG)

-

Central Evaluation and Information Group (ZAIG)

- Department XII - Central Information / Storage. Archive unit, responsible for central verification and information about recorded persons and registered files

- Department XIII - Central Computing Station

- Department M - Postal Control

- Department PZF (1962–1983), control of parcels, parcels and wraparounds as well as western print products, from 1983 merged with Department M

- Legal body

- Central coordination group (ZKG) - Combating flight and relocation

- Central Operational Staff (ZOS)

- Headquarters Reconnaissance - Foreign Espionage (HVA)

Despite the principle of isolation that is common in intelligence services, the respective areas of responsibility were in part closely related to one another. Although the technical guidance and coordination measures were carried out by the relevant central service units, the individual departments remained subordinate to the head of the associated district administration or one of his deputies in accordance with the territorial principle.

Prisons

The central Stasi remand prison was in Berlin-Hohenschönhausen . In a total of 17 pretrial detention centers, among other things, “solidified hostile-negative persons” were particularly closely guarded in order to prevent actions that were effective in the public eye.

education

Training institutions

On June 16, 1951, Walter Ulbricht opened the "School of the Ministry for State Security" in Golm near Potsdam in the presence of Wilhelm Zaisser . Ernst Wollweber, Zaisser's successor, renamed it “ University of the Ministry for State Security ” in 1955 , although at that time it was not a university in the true sense of the word. It was not until 1963 that a diploma could be obtained. Since June 1965 it has been externally known as the “ Potsdam University of Law ”. Internally from 1976 to 1989 the name "College of the Ministry for State Security" was used. On June 18, 1968, the university was granted the right to award doctorates (Dr. jur. ( Doctorate A ), from June 1, 1981 Dr. sc. [Scientiae] jur. [Juris] ( doctorate B )). All work was subject to the usual confidentiality rules of an intelligence service. The aim of this course was to train future MfS officers in leading positions ( lieutenant colonel and higher).

By 1961, a chair for “Legal Education”, a “Criminalistics” working group and institutes for Marxism-Leninism , law and specialty disciplines were established. In 1988 there were chairs for "Basic Processes of Political-Operational Work", "Espionage", "Political and Ideological Diversion Activities (PID)", "Political Underground Activities (PUT)" and "Basic Issues of Work in and After the Operation Area".

On June 19, 1970 the "Legal College of the Ministry for State Security" was founded and opened on November 4, 1970 by Erich Mielke. It was affiliated with the Potsdam Law School. It was possible to complete a technical college or a distance learning course. The prerequisite for admission was previous participation in the MfS. By 1984 there were 6,343 graduates, according to projections it was around 10,000 by the time the school was closed.

Education and Pay

Sometimes students received candidate payments, especially future Stasi officers. Even the student salary was around 1100 East Marks above the GDR average. There were three academic paths: studying at the MfS university , distance learning at the same and studying at one of the fully legendary MfS sections (faculties) at a university. An example of a legendary MfS section at a normal university was the Criminology Department at the Humboldt University in Berlin , which outwardly was a normal civilian section, but in reality, including the entire teaching staff, was in fact a MfS service unit.

The military service could be done with the MfS, for example with the guard regiment or with the guard and security units ( WSE ). Depending on the district, these units had between 50 and 300 men, were subordinate to the district administrations (BVs) and were used by MfS offices to secure property.

equipment

Kristie Macrakis examined the technical equipment of the Stasi against the background of her thesis “that the Cold War also resulted in a growing dependence of the secret services on technology”. She deals with transport containers for equipment, cameras, invisible ink and radio electronics, eavesdropping technology , chemical and radioactive marking of opponents of the regime and the process of odor differentiation , for which odor archives were set up by dissidents in order to narrow the circle of suspicious people. Suspicious citizens created odor reserves in order to be able to use specially trained dogs, for example. B. to locate the publisher of system-critical leaflets. Computers like the BSP-12 were also used from the late 1980s.

In 1968 the MfS obtained a mainframe computer from the French manufacturer General Electric Bull . In 1969, three Siemens S4004 mainframes were purchased for foreign and western espionage, which were officially bought for the Ministry of Science and Technology at a price of 23 million Deutschmarks . The large memory-oriented, list-organized input method GOLEM, also developed by Siemens , was used as software . 1973 began the establishment of the information research system of HV A , Sira .

Device for the conspiratorial recording of conversations with a filler microphone, which is connected to the Memocord k72 tape recorder . The switch (red) designed by the MfS itself controlled the memocord.

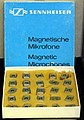

Box of magnetic microphones Sennheiser MM 26 for building bugs.

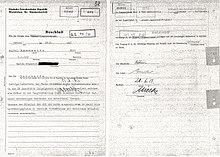

Photo table of Department M - Post control. Letters were photographed and thus u. a. a manuscript memory was created. So should cover addresses tracked foreign intelligence services or recognized unauthorized "contacts with the West" (here, the handwriting inside of the letter was not true in most cases with the envelopes match).

The telegram was an essential means of communication in the GDR, as there were hardly any telephone connections. Every incoming telegram in the Leipzig district was recorded by the MfS by telex . In order to cope with the flood of telegrams, the device shown in the picture was developed for evaluating telegrams.

The Russian photo sniper 12 is a Zenit 12 S SLR camera with a 300 mm telephoto lens and shoulder tripod , for unnoticed photography from a great distance.

Part of a telephone monitoring system of the technical department 26 of the MfS, where telephone calls could be stored on commercially available cassettes .

Radio clock for recording the time stamp for audio recordings that was displayed during playback. Remarkable: Sender 1 (GDR) and Sender 2 (Federal Republic) with automatic switching, so that the clock continued to work even after the end of the GDR. Manufacturer VEB Steremat

Basics and instructions

Legal bases

The dictatorship of the workers 'and peasants' state in the GDR was based on the principles of democratic centralism , control or limitation of state power through the separation of powers was rejected. The MfS was therefore not subject to any parliamentary or administrative legal control and carried out police and public prosecution tasks itself . The surveillance and prosecution of party members were allowed, such operations had to be approved by the department heads ( lieutenant colonel and higher).

In its self -image, the SED assumed that it was in possession of the truth with Marxism-Leninism and that it knew the laws of history , from which it derived its monopoly of leadership. The orders and instructions of the Politburo, which were to be followed strictly and uncritically, were the binding basis for the work of the MfS. The statute of the MfS from 1969 stipulated that the SED program and the resolutions of the Central Committee (ZK) and the Politburo are guidelines for the secret police work of the MfS. These resolutions were presented by party functionaries to the responsible heads of the MfS, whereby the political priorities of the intelligence work, the political and social scope for action as well as the norms of the secret police activity to be observed were determined.

The legal basis for the activities of the MfS was formed by the “Law on the Formation of a Ministry for State Security”, the statutes of the SfS / MfS of 1953 and 1969 (which were subject to the strictest confidentiality and in which the secret service powers were established by the government or the National Defense Council ) as well as the Code of Criminal Procedure and the People's Police Act of 1968, Article 20 of which endowed the members of the MfS with police powers.

Employees and victims

The MfS last had 91,015 full-time employees (as of October 31, 1989).

Employees (selection)

Full-time employees

- Wilhelm Zaisser - Minister for State Security from February 1950 to July 1953

- Ernst Wollweber - State Secretary for State Security from July 1953 to November 1955, then Minister for State Security until October 1957

- Erich Mielke - Minister for State Security from November 1957 to November 1989

- Hermann Gartmann - Deputy Minister for State Security 1951–1957 (?)

- Otto Last - Deputy Minister for State Security 1951–1957 (?)

- Rudolf Menzel - Deputy Minister for State Security 1952–1956 (?)

- Martin Weikert - Deputy Minister for State Security 1953–1957

- Otto Walter - Deputy Minister for State Security 1953–1964

- Markus Wolf - Deputy Minister for State Security 1953–1986, Head of Foreign Espionage (HVA) 1951–1986

- Bruno Beater - Deputy Minister for State Security 1955–1982

- Fritz Schröder - Deputy Minister for State Security 1964–1974

- Alfred Scholz - Deputy Minister for State Security 1975–1978

- Rudi Mittig - Deputy Minister for State Security 1975–1989

- Gerhard Neiber - Deputy Minister for State Security 1980–1989

- Werner Großmann - Deputy Minister for State Security 1986–1989, last head of the HVA

- Wolfgang Schwanitz - Deputy Minister for State Security 1986–1989, Head of the Office for National Security 1989–1990

- Horst Felber - 1st secretary of the SED district leadership in the Ministry for State Security 1979–1989

- Joseph Gutsche - headed the department for special uses from 1953 to 1955 (underground activities in the Federal Republic of Germany)

- Karl Zukunft - Head of the News Department 1964–1989

- Lutz Heilmann - the first former Full-time (HA PS), which in the German Bundestag was elected

- Werner Kukelski - First Head of HA VI Counterintelligence

Known employees in the Federal Republic of Germany

- Walter Barthel - journalist

- Gerhard Baumann - mistakenly believed to have been recruited by the secret service of the office of the French Prime Minister and delivered u. a. Internals from the Ministry of Defense and BND documents to it by the BND Vice President Paul Munster man had been made available

- Lorenz Betzing - civil security guard in partly security-sensitive Bundeswehr objects

- Hagen Blau - spy in the Foreign Office

- Eugen Brammertz - German Benedictine Father of the Trier Abbey of St. Matthias and journalist, working as IM "Lichtblick" in the Vatican

- Josef Braun (politician, 1907) - member of the German Bundestag, informed the MfS about events in the Berlin SPD party and state executive committee and about the activities of Willy Brandt

- William Borm - member of the FDP federal executive committee, member of the Bundestag

- Friedrich Cremer - Member of the Bavarian State Parliament (SPD)

- Christel Broszey - Chief Secretary of Kurt Biedenkopf

- Klaus Croissant - Lawyer

- Anton Donhauser - German politician (Bavarian party or CSU) and agent

- Dieter W. Feuerstein - graduate engineer at Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm , responsible for security

- Gerhard Flämig - member of the Bundestag for the SPD, as a so-called nuclear spy

- Reiner Fülle - Accountant at the Karlsruhe Research Center , known as "Glatteisspion", provided information about the reprocessing technology of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Gabriele Gast - Government Director in the Federal Intelligence Service

- Karl Gebauer - spied as a security officer for the company IBM special systems in Wilhelmshaven

- Otto Graf - initially belonged to the KPD and later for the SPD to the German Bundestag, worked under the code name "Herzog" as a spy for the GDR

- Rolf Grunert - Federal Chairman of the Association of German Criminal Investigators , SED member since 1947

- Christel Guillaume - secretary in the party office of the SPD Hessen-Süd

- Günter Guillaume - spy with Willy Brandt

- James W. Hall - Telecommunications intelligence of the USA against the GDR in West Berlin

- Karl Hauffe - Professor of Applied Physical Chemistry and Institute Director at the University of Göttingen

- Peter Heilmann - Head of Studies at the Evangelical Academy in West Berlin

- Brigitte Heinrich - journalist, politician of the Greens, member of the European Parliament

- Odfried Hepp - Illumination of the right-wing scene in the Federal Republic of Germany

- Horst Hesse - double agent at the Military Intelligence Division in Würzburg, stole two safes in 1956 with the entire agent file of the MID

- Gero Hilliger - from 1977 to the end of 1989 as an agent under the code name "IMB Brunnen", spied on a. a. the politician Dieter Dombrowski

- Hanns-Dieter Jacobsen - political scientist at the Free University of Berlin

- Gerhard Kade (IM “Super”) - economist, “Managing Director” of the Generale Group for Peace

- Anetta Kahane - 1974 to 1982 IM "Victoria" (spied on, among others, West Berlin students from the Free University of Berlin )

- Hans-Adolf Kanter - lobbyist and later authorized signatory of the Flick Group , close friend of the manager Eberhard von Brauchitsch

- Joachim Krase - IM "Günter Fiedler" in the military counterintelligence service

- Klaus Kuron - employee of the counter-espionage department at the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

- Karl-Heinz Kurras - spy with the West Berlin police, killed Benno Ohnesorg on June 2, 1967

- Ursel Lorenzen - employee at the NATO headquarters in Brussels

- Horst Meier - agent and visual artist

- Holger Oehrens (IM “Alf”) - TV and newspaper journalist, HR, Bild-Zeitung

- Johanna Olbrich (alias Sonja Lüneburg) - spy with Martin Bangemann

- Lilli Pöttrich - lawyer in the Foreign Office

- Hannsheinz Porst - member of the FDP and the SED

- Armin Raufeisen - geophysicist at Preussag

- Klaus Kurt von Raussendorff - spy in the Foreign Office

- Ursula Richter - Chief Secretary at the Association of Displaced Persons

- Rainer Rupp (IM "Topas") - spy at NATO headquarters

- Karlfranz Schmidt-Wittmack - Member of the German Bundestag ( Security Committee ) fled to the GDR in 1954; Vice-President of the Chamber for Foreign Trade of the GDR

- Dirk Schneider - politician with the Greens

- Bernd Stange , soccer coach

- Dietrich Staritz - political scientist

- Artur Stegner - member of the Bundestag (for the FDP), offered himself as an informant due to financial problems of the HV A, the cooperation was soon ended because his reports were worthless

- Julius Steiner (politician) - for the CDU in the German Bundestag, spied as a double agent under the supervision of the BND since 1972 the CDU as IM "Theodor" for the MfS and received twice for his abstention in the vote of no confidence against Willy Brandt

- Leo Wagner Member of the German Bundestag, bribed by the Stasi with 50,000 DM on the occasion of the vote of no confidence in Willy Brandt in 1972

- Lothar Weirauch - as FDP federal manager and ministerial official in the Federal Republic, he was a Stasi agent in the GDR

- Karl Wienand - Member of Parliament, Parliamentary Director of the SPD

- Herbert Willner - in the FDP federal office, later in the FDP-affiliated Friedrich Naumann Foundation as a speaker

- Herta-Astrid Willner - Secretary to the Head of Dept. 3 in the Federal Chancellery

- Bruno Winzer - major, spy in the Bundeswehr, key witness of the SED propaganda for West German aggression plans in the GDR

- Karlfranz Schmidt-Wittmack - member of the German Bundestag for the CDU, from 1952 informant of the HVA, applied for asylum in the GDR in 1954

- Peter Wolter - journalist, provided internal findings from the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution

- Hüseyin Yıldırım - Brokered intelligence to Headquarters for $ 300,000 top-secret documents provided by James W. Hall

Defector

- Jeffrey Carney - former corporal of the US Air Force's telecommunications reconnaissance in the Marienfelde radar facility in Berlin

- Werner Stiller - Lieutenant of the HVA and probably a double agent. His escape from the GDR in 1979 is still considered one of the most spectacular espionage affairs to this day.

- Max Heim - Head of Unit, settled in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1959, where he disclosed important structural information about the HV A.

- Karl-Christoph Großmann - Colonel in the MfS named the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution in 1989 a. a. the real names of Gabriele Gast, Klaus Kuron, Alfred Spuhler and Ludwig Spuhler and Hansjoachim Tiedge

- Hansjoachim Tiedge - formerly head of the counter-espionage department at the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution .

- Horst Schuster - Director of Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH until October 1980, then employee of BERAG; Triple agent - for the CIA as "Pfaff", with the MfS as IM "Sole" and with the BND as "Odysseus". Schuster was able to flee the GDR in 1983.

Known victims

- Rudolf Bahro (1935–1997), civil rights activist in the GDR, was deported to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1979 after imprisonment.

- Jörg Berger (1944–2010), soccer player and coach, fled to the West in 1979 and was exposed to threats organized by the Stasi in the West

- Wolf Biermann (* 1936), songwriter, was expatriated in 1976

- Bärbel Bohley (1945–2010), civil rights activist and painter

- Karl-Heinz Bomberg (* 1955), doctor, songwriter and author

- Heinz Brandt (1909–1986), editor, kidnapped to the GDR and imprisoned for years

- Klaus Brasch ( 1950 - 1980 ), actor

- Matthias Domaschk (1957–1981), civil rights activist

- Lutz Eigendorf (1956–1983), soccer player

- Karl Wilhelm Fricke (* 1929) publicist and editor was forcibly kidnapped from West Berlin by the MfS in 1955 and sentenced in a secret trial

- Jürgen Fuchs (1950–1999), writer and civil rights activist

- Michael Gartenschläger (1944–1976), escape helper

- Ines Geipel (* 1960) athlete and writer, subjected to dismantling measures after escape plans became known

- Wolfgang Harich (1923–1995 in Berlin), philosopher, journalist, convicted in 1957 in a show trial for “forming a conspiratorial anti-state group”

- Werner Hartmann (1912–1988), founder and head of the Molecular Electronics Department, dismissed without notice due to a Stasi intrigue

- Florian Havemann (* 1952), writer and painter, critic of the regime and political prisoner in the GDR; Son of Robert Havemann

- Robert Havemann (1910–1982), chemist, resistance fighter against National Socialism and critic of the regime in the GDR

- Hans-Joachim Helwig-Wilson (1931–2009), photojournalist, lured to East Berlin by the Stasi, sentenced to 13 years in prison

- Stefan Heym (1913–2001), writer

- Ralf Hirsch (* 1960), civil rights activist, the MfS planned his assassination

- Gert Hof (1951–2012), light art artist and director

- Peter Huchel (1903–1981), poet and editor

- Roland Jahn (* 1953) - civil rights activist, expatriated from the GDR by force in 1983

- Walter Janka (1914–1994) dramaturge and publisher, arrested and sentenced for counterrevolutionary conspiracy

- Freya Klier (* 1950), author and director as well as GDR civil rights activist, several attempts at murder by the MfS

- Reiner Kunze (* 1933), writer and dissident in the GDR

- Theo Lehmann (* 1934), Protestant pastor

- Vera Lengsfeld (* 1952), civil rights activist

- Walter Linse (1903–1953), lawyer

- Erich Loest (1926–2013), writer

- Monika Maron (* 1941), writer, she refused to name the GDR citizens involved, after which she was monitored and prosecuted

- Bernd Moldenhauer (1949–1980) - dissident, murdered by an unofficial employee of the GDR State Security

- Sylvester Murau (1907–1956) - Major in the MfS who, after fleeing to the West, was kidnapped, sentenced to death and executed in the GDR

- Gerulf Pannach (1948–1998), songwriter and lyricist

- Gerd Poppe (* 1941), civil rights activist

- Ulrike Poppe (* 1953), civil rights activist

- Siegfried Reiprich (* 1955) civil rights activist and writer

- Dieter Rieke (1925–2009), social democratic politician

- Michael Sallmann (* 1953), poet and songwriter

- Jessie George Schatz (1954–1996), Military Liaison Officer

- Edda Schönherz (* 1944), TV announcer and author in the GDR

- Manfred Smolka (1930 - July 1960), sentenced to death in a show trial for alleged military espionage and executed

- Wolfgang Templin (* 1948), civil rights activist and publicist

- Werner Teske (1942–1981), captain of the Stasi and alleged spy

- Rudi Thurow (* 1937), escaped border soldier, several attempts to murder him failed

- Bettina Wegner (* 1947), songwriter

- Wolfgang Welsch (* 1944), political prisoner and escape helper

- Christa Wolf (1929–2011), writer

- Jens-Paul Wollenberg (* 1952), musician

literature

- Christian Adam , Martin Erdmann (ed.): Restricted areas in the GDR. An atlas of the locations of the Ministry for State Security (MfS), the Ministry of the Interior (MdI), the Ministry of National Defense (MfNV) and the Group of Soviet Armed Forces in Germany (GSSD) (= BF informs 34). Developed by Horst Henkel and Wolfgang Scholz, Federal Commissioner for Stasi Records, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-942130-77-6 .

- Jürgen Aretz , Wolfgang Stock : The forgotten victims of the GDR. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1997, ISBN 3-404-60444-X .

- Thomas Auerbach , Matthias Braun, Bernd Eisenfeld , Gesine von Prittwitz, Clemens Vollnhals : Anatomy of State Security: History, Structure and Methods - Department XX: State apparatus, bloc parties, churches, culture, “political underground”. The Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the Former German Democratic Republic (BStU), Department of Education and Research, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-942130-13-4 .

- Thomas Auerbach: Task Force on the invisible front. Ch. Links, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-86153-183-6 .

- Klaus Behnke , Jürgen Wolf (ed.): Stasi in the schoolyard. Ullstein, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-548-33243-9 .

- Gary Bruce: The Firm. The Inside Story of the Stasi. The Oxford Oral History Series, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2010, ISBN 978-0-19-539205-0 .

- Gregor Buß: Catholic priests and state security. Historical background and ethical reflection . Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2017, ISBN 978-3-402-13206-7 .

- Torsten Diedrich , Walter Suess (ed.): Military and state security in the security concept of the participating states of the Warsaw Pact . On behalf of the Military History Research Office and the Federal Commissioner for the Documents of the State Security Service of the Former GDR, Links, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-86153-610-9 .

-

Roger Engelmann (Ed.): The MfS Lexicon. Terms, persons and structures of the state security of the GDR. Ch Links Verlag, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-86153-627-7 .

- Roger Engelmann, Bernd Florath , Helge Heidemeyer , Daniela Münkel , Arno Polzin, Walter Süß: The MfS Lexicon. 3rd, updated edition. Berlin 2016. Ch. Links Verlag, ISBN 978-3-86153-900-1 , online version .

- Peter Erler , Hubertus Knabe : The forbidden district of the Stasi restricted area Berlin-Hohenschönhausen. Jaron, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-89773-506-7 .

- Günter Förster: The Law School of the MfS. BStU, Department of Education and Research, Berlin 1996.

- Rahel Frank, Martin Klähn, Christoph Wunnicke: The resolution. The end of state security in the three northern districts. Schwerin 2010, ISBN 978-3-933255-31-0 .

- Karl Wilhelm Fricke: file inspection. Reconstruction of a political persecution . 4. through and actual Ed. Ch. Links, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-86153-099-6 .

- Stefan Gerber: To train qualified lawyers at the MfS University (Juristic University Potsdam). Nomos-Verlag-Ges., Baden-Baden 2000, ISBN 3-8305-0008-4 .

- Gunter Gerick: SED and MfS. The relationship between the SED district leadership in Karl-Marx-Stadt and the district administration for state security from 1961 to 1989 . Metropol, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86331-127-8 .

- Jens Gieseke : The Ministry for State Security (1950–1990). In: Torsten Diedrich, Hans Ehlert , Rüdiger Wenzke (eds.): In the service of the party. Handbook of the armed organs of the GDR. Ch. Links, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-86153-160-7 , pp. 371-422.

- Jens Gieseke : The GDR State Security. Shield and sword of the party. Federal Agency for Political Education, Bonn 2000, ISBN 3-89331-402-4 .

- Jens Gieseke: The full-time employees of the State Security. Personnel structure and living environment 1950–1989 / 90. Ch. Links, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-86153-227-1 ( on Google Books ).

- Jens Gieseke (Ed.): State Security and Society. Studies on everyday rule in the GDR. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-35083-6 .

- Jens Gieseke: The Stasi 1945–1990. Pantheon, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-570-55161-5 .

- with Andrea Bahr: The State Security and the Greens. Between SED-West politics and East-West contacts . Ch.links, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-86153-842-4 .

- Arik Komets-Chimirri: Operation False Flag. How the KGB infiltrated the West. be.bra Wissenschaft verlag, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-95410-039-2 .

- Uwe Krähnke, Matthias Finster, Philipp Reimann, Anja Tschirpe: In the service of the state security. A sociological study of the full-time employees of the GDR secret service. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt / New York 2017, ISBN 978-3-593-50522-0 .

- Jenny Krämer / Benedikt Vallendar : Life behind walls. Everyday work and private life of full-time employees of the Ministry for State Security of the GDR , Klartext Verlag Essen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8375-0959-5 .

- Frank Joestel (arrangement): The GDR in the eyes of the Stasi. The secret reports to the SED leadership. Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-37502-0 .

- Christian Halbrock : Stasi City - The MfS headquarters in Berlin-Lichtenberg - A historical tour. Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-86153-520-1 .

- Hagen Koch , Peter Joachim Lapp : The guard of Erich Mielke. The military-operational arm of the MfS. The Berlin Guard Regiment "Feliks Dzierzynski". Helios, Aachen 2008, ISBN 978-3-938208-72-4 .

- Peter Joachim Lapp: Border regime of the GDR. Helios, Aachen 2013, ISBN 978-3-86933-087-7 .

- Hubertus Knabe : West work of the MfS. The interplay of "education" and "defense" . Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-86153-182-8 .

- Hubertus Knabe: The discreet charm of the GDR. Ullstein, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-549-07137-X .

- Hubertus Knabe: The infiltrated republic. Ullstein, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-549-05589-7 .

- Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk : Stasi specifically. Surveillance and repression in the GDR. Beck, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-406-63838-1 .

- Henry Leide: Nazi Criminal and State Security. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-525-35018-X .

- Kristie Macrakis: The Stasi secrets: methods and technology of GDR espionage. Herbig 2009, ISBN 978-3-7766-2592-9 .

- Horst Müller et al. (Hrsg.): The industrial espionage in the GDR: The scientific-technical clearing up of the GDR. edition ost , Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-360-01099-5 .