Homicide

A homicide offense is an offense in criminal law that criminalizes an act against a person's life. The formation of the offenses for the various homicides differs from legal system to legal system, in particular there are homicides in many legal conceptions that are not murder (accidental or negligent act resulting in death , according to some legal systems also deliberate killings in which the offense of murder is not fulfilled) . There is no globally applicable definition.

Legal circles

Similarities can be found in legal circles :

German legal circle

In the legal systems of the states of the German legal circle listed here , the most prominent offenses of homicides each belong to a system of basic offense , privilege (s) with less threatened punishment and usually also qualification with higher threat of punishment. Whether a specific crime is to be described as murder or manslaughter, for example, depends on the respective legal system.

- Germany: manslaughter (basic offense), murder (qualification), killing on request (privileged status).

- Austria: murder (basic offense, there is no qualification), manslaughter (privileged status); Homicide on request , involvement in suicide , killing of a child at birth , negligent homicide under particularly dangerous circumstances (qualifications of homicide); Generic term: Offenses against life and limb (without special limitation to acts resulting in death, in particular §§ 75-81 StGB )

- Switzerland: intentional homicide (basic offense), murder (qualification), manslaughter (privileged status).

In the legal systems of the German legal circle, there are in particular many offenses that make killing a person a criminal offense, but do not require intent (see intent (Germany) ) with regard to causing death. In each of the three jurisdictions there is an offense called negligent homicide . Further of these negligent homicides (in a broader sense including qualifications for success ) are, for example, bodily harm resulting in death in Germany and bodily harm resulting in fatal outcome in Austria . An overview of the numerous homicides for the legal system in Germany alone can be found under Killing offenses (Germany) .

All negligent homicides are not referred to as murder in the popular or colloquial sense .

Common law

In England and Wales as well as Northern Ireland a distinction is made between murder , voluntary manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter (in Scottish law homicide instead of manslaughter ).

In the United States , homicides are divided into first degree murder and second degree murder . Third degree murder is only found in a few states in which the crime of murder is not divided into two, but three levels.

Legal history

Antiquity

The development of legal history ties in with the archaic traditions from the Codex Hammurapi and the Bible . The common principle is the talion . The death of the victim is rewarded with the death of the perpetrator. The transition from kinship law to the social concept of a homicide is impressively evident in Lex Numae 16 : Whoever kills a free person is to be punished like a killer of relatives (around 600 BC). In the Bible, however, a distinction is made between intentional and accidental killing in the Book of Exodus . This passage can be found in the various translations, for example, under headings such as "Murder and manslaughter" ( Ex 21.12-27 EU ), "Offenses against life and limb" ( Ex 21.12-27 LUT ) or "Provisions on manslaughter and bodily harm “( Ex 21.12-27 SLT ; the Hebrew word רֹצֵ֣חַ 'murderer' used in Num 35.16-18 EU corresponds to Art. 300 StGB-IL רֶצַח 'murder'). In order to protect the perpetrator, who did not act with intent or deceit, from blood revenge , the establishment of cities of refuge is also ordered ( Ex 21.13–14 HFA , Ex 21.13–14 GNB ).

In the late Republican period of Rome (100 BC) the Leges Corneliae von Sulla show the first stages of a moral act of killing, namely poisoning ( veneficium ) and violent murder ( sicarium ). Later in the reign of Emperor Hadrian , subjective characteristics such as forethought ( propositum ) and affect ( impetus ) become decisive. This almost 2000 year old development was still used in Germany when the Imperial Criminal Code was created in 1871 and is still traced in the literature today.

Germanic law

Germanic law did not yet have a sophisticated differentiation between intent and negligence, but was based on liability for success : "The act kills the man". However, there was an awareness of the distinction between malicious intent and mere oversight. However, this distinction was not made according to the presumed internal motives of the perpetrator, but according to characteristic external features. The external characteristics of the murder were seen as the fact that the perpetrator tried to conceal the crime, for example by trying to move the corpse aside. The cases of approximate work correspond to today's negligence category . Approximately work was used as a basis if, according to the typical external circumstances, the killing situation could not be based on malicious intent, such as accidents while falling trees or hunting. Up until the 12th century, the perpetrators, who otherwise would have been victims of blood revenge, were required to receive a tiered “ wergeld ” (ahd. Who man, man; Latin vir man). For this purpose, the perpetrator had to free himself from the charge of bad intent by taking an oath of cleansing. Sometimes the cases of an approximate work were also equated with the self-defense cases.

Islamic law

The Koran provides retribution ( Qisās ) for deliberate killing , forgiveness is possible (Suras 2: 178 and 5:45), and blood money for unintentional killing ( Diya , Sura 4:92). Proceeding from this, Islamic jurisprudence ( Fiqh ) has produced rules that are now being converted into laws by Sharia- loyal states such as Sunni Pakistan or Shiite Iran .

Middle Ages and early modern times

In the High Middle Ages, the murder was considered a secret killing, with the perpetrator hiding the body to cover up the crime.

With the end of the Middle Ages, the Roman doctrine was received again, so that murder finally appeared in the neck court order of Emperor Charles V ( Constitutio Criminalis Carolina [Art. 134, 137 CCC]) as killing with forethought . The “fursetz” mentioned there was not intent, but foresight.

This regulation continued over the Prussian general land law in the penal code of the North German Confederation ("Thötung durch deliberation"). In the Reich Criminal Code, Section 211 then read: “Anyone who deliberately kills a person will be punished with death for murder if he deliberately carried out the killing.” (In contrast, the provision in Section 212 for manslaughter was: “Whoever willfully kills a person, if he did not carry out the killing with deliberation, he will not be punished for less than five years for death with imprisonment. ") Murder aimed at deliberation, manslaughter was seen as an act of affect. It was not until 1941 that this regulation was replaced by the National Socialist regime with the current state of affairs regulation. The version of Section 211 Paragraph StGB largely corresponds to the preliminary draft for a Swiss StGB from 1896.

Comparative law analysis

Designations

Purely linguistically, four types of designation for homicides can be distinguished:

- 1. Result-related: Derivation (alone) from a root with the meaning ' dead / death / die '

- 2. action-related: derivation from an independent root meaning ' slain / kill '

- dt. death blow , engl. man slaughter , netherlands dood slag (to idg. * slak- )

- isl. man dráp , dan. mand drab , swed. dråp (to germ. * drepan )

- lat. homi / infanti / parri cidium , engl. / French homicide , Spanish homicidio , Italian omicidio (to Latin caedere )

- russ. убийство ubistwo , czech. zabití (next to vražda ), croat. ubojstvo (to idg. * bhei [ə] -, * bhī- )

- arab. قتل qatl

- hochchin .杀人shārén , jap.殺人satsujin , kor. 살인 salin ; indon. pembunuhan

- 3. Type of debt related: engl. criminal negligence causing death

- 4. Further reference: Derived from the name of the medieval sect of the Assassins

Basic structures of premeditated homicide

Legislative engineering

All major legal systems know an offense of the structure "whoever kills another person willfully, is [...] punished" with the elements 1. human 2. other and 3. deliberate killing. In the same way, however, there is consensus in all legal systems that not all forms of intentional homicide are punishable in the same way. The basic structure must therefore be modified in certain cases and different case constellations weighted differently. Three basic types can be distinguished:

- Single stage / unitary offense : In the case of a unitary offense, neither a particularly serious nor a particularly mild form of willful killing is highlighted in the offense. This model is used in Denmark, for example: According to Section 237 Straffeloven, intentional homicide is subject to imprisonment from 5 years to life . In order to avoid legal uncertainty despite this wide range, there is therefore only a single instance court that specializes in homicides.

- Two-stage: In the two-stage model, forms of killing that are rated as particularly mild or particularly severe are classified as separate offenses. The two-tier type is in turn conceivable in two ways: as qualification-related or as privileged-related: The design is qualification-related if a particularly severe form is excluded from the basic offense and transferred to a separate offense and the basic offense includes the mild and medium forms. A model is privilege-related if it assigns the medium and more severe forms to the basic offense and includes particularly mild forms in a separate offense (example: Austria).

- Three-tier: There is a separate offense for each qualification, basic offense and privilege, which includes the particularly serious, medium and mild forms of killing (example: Switzerland).

In terms of legislation, a general clause-like phrase can be used for qualification or privilege (e.g. "killing with deliberation") or the qualifying / privileging features can be attached to a detailed casuistic list. The trade-off between legal certainty and the elasticity of the norm, i. H. Individual justice arises from the respective political understanding of the separation of powers between the legislature and the judiciary .

Not every gradation has to be assigned its own name. Conversely, the word assigned to an offense says little about the scope of punishment and the severity or mildness of the form of killing, but rather serves as a striking effect than a legal assessment.

murder

In the Germanic area , 'murder' usually describes the form of deliberate killing that is rated as the most severe . In the technical-legal sense, there are four types of use:

- for all qualifications, but also only for these (example: Switzerland Art. 112 ),

- only for qualifications, but only part of them (example: Germany 1871, § 211 Mord in addition to § 215 Ascendant Death),

- for all non-privileged cases with privileged two-tier status (examples: Austria § 75 , Sweden Chapter 3 § 1 , England)

- in the case of a single offense for all intentional killings (example: ČSSR 1961 § 219 Vražda).

Linguistically, the Indo-European root * mer- has been developed for the term Mord (see also English murder, French meurtre , but the use of which does not coincide with German murder ) . It stands for the meaning field 'dead, lifeless' . (Examples: Latin mors - death, mortuus - dead , Greek βροτός ( brotós ) - mortal (→ Ambrosia ), Czech smrt, úmrtí - death, mr't - dead meat, fire, mrtvèti - freeze, mrtviti - kill, mrtvola - Corpse ) The German word murder is therefore not a loan word after the Latin mors "death", but both go back to the common Indo-European root. The root * murþa , which is already connected with the act of killing, was reconstructed for the ancient Germanic language . The Gothic maurþr is related to both the German word Mord and the English murder . The term “murder” in its current spelling appears in 1224 in the Treuga Henrici . From “Mord” the outdated cry for help is “ Mordio! “Derived (the extension by the -io makes the interjection callable - cf. Feurio ). Nowadays he is only used in the idioms screaming and screaming murder.

In order to legitimize the maximum sentence for certain cases of intentional homicide, the classic consideration criterion was available in numerous legal circles for a long time . The inadequacy of its use in its pure form has recently led to the development of reprehensible and dangerous criteria and combination models. The main point of criticism of the consideration criterion is that "confusion, ambiguity and uncertainty of the meaning and application of (malice) premediation and deliberation" come at the end of every interpretation of such a constituent element. Its use has therefore been modified in two directions: In the former, the consideration criterion is largely downgraded to a mere indication; With this interpretation of the feature, “even a single second” is sufficient, but to confirm the maximum penalty, further features must be added in addition to this indication. In the second still existing use of the criterion, it appears in a qualified form: The preliminary consideration must extend over a certain period of time. The Portuguese código penal offers a particularly interesting application of the feature :

«2 - É susceptível de revelar a especial censurabilidade ou perversidade a que se refere o número anterior, entre outras, a circunstância de o agents: […]

i) Agir […], com reflexão sobre os meios empregados ou ter persistido na intenção de matar por mais de vinte e quatro horas; »

“2 - The particular accusability or perversity mentioned in the previous paragraph can be inferred from the fact that the perpetrator […]

i) […] acts with consideration of the means used, or that he intends to kill for more than 24 hours maintains "

Often the most severe form of killing does not expire .

homicide

Manslaughter (Engl. Manslaughter ) is widespread in its use the least uniform and in general usage the least. In German law, for example, the word is used for intentional killings that are neither murder nor killing on request, in Switzerland, on the other hand, for privileged cases. Overall, it can be said: If the word is used, it at least also includes the privileges.

Deliberate Killing

In the legal systems of states such as China, Korea , Japan , Denmark , Poland , Russia and Turkey , the term murder is used for a criminal offense without prevalence or tradition; regularly one speaks here only of the willful killing. The term 'intentional killing' (English homicide, French homicide, Spanish homicidio ) can be used in three variants: a) as a comprehensive non-statutory generic term for all deliberate homicides, b) as a comprehensive legal generic term for all deliberate types of killing and c) for the middle range between particularly severe and particularly mild form of killing (example: Switzerland).

Typical models

A total of six basic constellations can be distinguished from the combination of the possible content and linguistic design options:

- The single-stage offense is designated with one word (example: Denmark),

- the two-tier model is used but both forms are denoted by the same word,

- the two-stage model is used and two different words are chosen for the designation (example: Austria),

- the three-stage model is chosen, but all forms are named the same (examples: AE-BT 1970 § 100 , Russia Art. 105 ff.),

- in the three-stage model two terms are used and

- the three-stage model is used and a corresponding triad of terms is assigned to it (example: Switzerland).

Basic structures of non-willful killing

Negligent homicide

The basic case of non-intentional homicide is negligent homicide (Germany § 222, Austria § 80, Switzerland Art. 117). Negligent acts are those who do not consider the consequences of their behavior due to negligent carelessness (unconscious negligence) or who do not take them into account (conscious negligence). Negligence presupposes the subjective predictability and avoidability of the disapproved success (cf. Austria § 6 , Switzerland Art. 12 Paragraph 3).

Culpable success qualification

In German and Austrian criminal law, there are offenses that require intent with regard to the basic offense (e.g. bodily harm, Germany § 227, Austria § 86), but only negligence with regard to the result of death (see Germany §§ 15 , 18 , Austria § 7 ). In Switzerland, these successful offenses were abolished in 1985, in Sweden as early as 1965.

Purely objective attribution

In addition, some legal systems have a purely objective liability for success . In the German area, too, in the past, all harmful consequences resulting from prohibited actions were attributed ( dolus indirectus or versari in re illicita ; Carpzov ). A similar regulation of common law was abolished in England and Canada, but is still widespread in the USA as the felony murder rule .

Tabular overview of relevant paragraphs in DE / AT / CH

| country | year | qualification | Basic fact | Privilege | Negligent homicide | Success qualification | tracking limitation period |

judicial jurisdiction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1941 | Section 211 murder | Section 212 manslaughter |

Section 213 ( standard example ) Section 216 |

Section 222 |

§ 227 u. a. (cf. § 74 GVG ) |

§ 78 | Sections 74 , 28 GVG |

|

|

1974 | Section 75 Murder |

Section 76 Manslaughter Sections 77 , 79 |

Sections 80 , 81 | §§ 86 , 87 u. a. | Section 57 | Section 31 StPO | |

|

|

1985 | Art. 112 Murder |

Art. 111 willful homicide |

Art. 113 Homicide Art. 114 , 116 |

Art. 117 | - | Art. 97 | Art. 19 StPO |

criminology

Due to the prominent position of murder as the destruction of a human life as the most reprehensible act, the most severe threat of punishment is provided in all criminal justice systems in Europe . Rarely (e.g. Austria) is there a heavier sentence for genocide . Since all European states belong to the Council of Europe (with the exception of Belarus), the death penalty has been abolished in almost all European countries (6th and 13th Optional Protocols to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)). Few countries have already abolished life imprisonment (e.g. Portugal and Croatia). The life sentence hardly corresponds to the legal reality. According to a study, life imprisonment is carried out in England for an average of 9 years, while in Germany it is an average of 21 years.

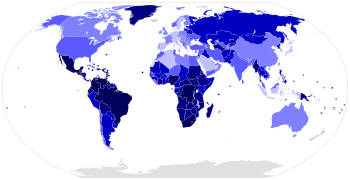

Frequency - international comparison

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) published an international study, including crime statistics, in relation to homicide (premeditated) in 2011 , the 2011 Global Study on Homicide . The study only records intentional homicide ( e.g., willful homicides or homicides with intentional involvement) and includes, in particular, only those crimes in which the perpetrator wanted to cause the death (or at least serious injury) of the victim.

The basis for the survey were clearly identified or completed murder cases per 1,000 inhabitants. According to this, the most people were murdered in Colombia with 0.617847 murders per 1,000 inhabitants, followed by South Africa (0.496008 per 1,000 inhabitants ), Jamaica (0.324196 per 1,000 inhabitants), Venezuela (0.316138 per 1,000 inhabitants) ) and Russia (0201534 per 1,000 inhabitants). With the highest number of murders within the European Union , the Baltic states ( Estonia 0.107277; Latvia 0.10393; and Lithuania 0.102863 per 1,000 inhabitants) ranked 7th to 9th. The United States of America was ranked 24th (0.042802) according to this statistic. In Germany (49th) 0.0116461 per 1,000 inhabitants were murdered in the specified period. Fewer people were killed by murder in Switzerland (56th). Austria is no longer listed in the statistics with fewer cases.

The statistics are to be viewed critically as they ignored several national factors influencing the figures, such as the different level and quality of the criminal investigation , the personnel, technical and material resources of the investigating authority (s) and the quality influenced by different factors the medical examination (s) to establish such a criminal offense, if this occurs at all.

Percentage of the continents in the world population and in the worldwide murders in 2011

Time and scene of the crime

A statistical relationship between month or season and the number of homicides has been the subject of numerous studies. However, the results of these studies often show contradicting results. The opposite view regards the alleged differences as not statistically relevant; the fluctuations are purely random fluctuations both between months and between seasons.

In contrast, most studies confirm that there are differences in the number of homicides over the days of the week. In North American studies, homicides on weekends showed a proportion of 60% to 80%; the number of homicides assumed a value of 50% on Fridays after 8 p.m. An increased number of homicides at weekends is also unanimously found in German studies. An analysis of homicides in Hamburg from 1950 to 1967 showed that 47% of all homicides occurred between Friday 8 p.m. and Sunday midnight. The Hamburg study also found a correlation between weekend crimes and the following criteria: weekend crimes mostly took place in an environment that was unfamiliar to the perpetrator and less often related to family members; The perpetrators and victims were significantly more often under the influence of alcohol. If one also differentiates the offenses according to the convicted offenses, the following picture emerges: Half of all physical injuries resulting in death occurred on the weekend, 29% of all manslaughter and 19% of all offenses convicted as murder. It is also noticeable that the deaths of loved ones and spouses are 41% above the expected value.

In all studies, the number of homicides correlates with the time of day: the vast majority of homicides occur between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m. at night. According to the Hamburg study, murder-suicide combinations that are evenly distributed over the times of day are excluded from this. The number of cases of bodily harm resulting in death is particularly high between 8 p.m. and 4 a.m.

Possible crime scenes - such as differences between town and country, different milieus or the remoteness of a crime scene - are far less characterized by a naturally occurring order than the time of the crime; Expected values are difficult to formulate. That is why the crime scene is regularly very difficult to record statistically. In this respect, however, the home and workplace occupy a special position, as most people spend a large part of their time here. In the Hamburg study, 11.4% of all homicides occurred in the workplace in 360 cases examined: 7.5% at the workplace of the victim, 2% at the common workplace and 2% at the workplace of the offender. The very different working environment of prostitutes means that these cases are not included in the statistics. In contrast, the apartment takes up a much larger space: in the Hamburg study, the proportion was 70%, other studies come to results between 40% and 50%. Within these cases, the shared apartment comes first, the victim's apartment second and the perpetrator's apartment third.

The low proportion of offenses in the workplace is explained for various reasons: For example, conflicts in the workplace would usually be less emotionally charged and therefore more accessible to an objective solution; In addition, the practice of work and the work discipline associated with it are already in conflict with the violent resolution of conflicts. These explanations are supported by the observation of the Hamburg study that in the cases of killing at work 40% of the perpetrators were released from their work due to illness, unemployment or vacation. The excellent position of the apartment is explained by the fact that homicides regularly arise from private conflicts in the immediate vicinity. This is supported by the fact that more than 90% of the murder-suicide combinations take place in the apartment, in the remaining cases between 60% and 70%. If one differentiates further within the apartment, according to the Hamburg study, the bedroom comes first with 19%, followed by the kitchen and living room with 12% each.

The offender

The scientific occupation of psychiatry with the perpetrators of homicides stems from their assessment work in criminal proceedings. The early psychiatric literature in particular revolves around the question of whether the killer personality exists as a separate type of person. Criticism of the attempt at such a classification arose from the problematic comparability of the most diverse possible case constellations: for example the robber who shoots his way free after a bank robbery; the mother who, from an apparently insoluble family dilemma, wants to take her children with her to death; the sexually motivated serial offender.

Studies that have examined and statistically evaluated a large number of offenders using validated methods are rare. Most of the early studies were based on the Rorschach test and, consequently, are fraught with controversies inherent in the test. Ferracuti has summarized the results of these tests as follows: egocentricity and lack of emotional control, lack of maturity and explosiveness, difficulty in contact, low tolerance for frustration and low rational control.

Investigations into the perpetrators of negligent homicide are also small in number; most rely on the perpetrators of road traffic offenses. The comparability of the perpetrators of negligent homicide and negligent bodily harm - act and guilt are alike, success of the act, i.e. H. Injury or death depend on chance - the investigation mass suggests that the perpetrators of negligent bodily harm should be expanded.

- See also

literature

- Final report of the expert group on the reform of homicides (Sections 211–213, 57a StGB) (PDF) June 2015

Legal history

- Michael Sommer (Ed.): Political Murders. From ancient times to the present . Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-18518-8 .

Comparative law

- Arnd Hüneke: The murder fact in comparison to other European norms. Criminological Research Institute Lower Saxony , Hanover 2003.

- Albin Eser , Hans-Georg Koch: The intentional killing offenses. A structural and criteria analysis comparing reform policy and law . In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law . tape 92 , 1980, pp. 491 ff .

- Günter Heine : murder and murder facts . In: Goltdammers Archive for Criminal Law . 2000, p. 303-319 .

- Günter Heine: Status and development of the murder facts: national and international . In: Sensitive and thinking criminal sciences : Gift of honor for Anne-Eva Brauneck . 1999, p. 315-352 .

- Jeremy Horder: Homicide Law in Comparative Perspective . Hart, Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-1-84113-696-7 .

- Nora Markwalder: Robbery Homicide. A Swiss and International Perspective . Schulthess Verlag, Zurich 2012, ISBN 978-3-7255-6500-9 .

- Rudolf Rengier : Exclusion of murder from willful killing? A comparative representation of Austrian, Swiss and German law . In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law . tape 92 , 1980, pp. 459 , doi : 10.1515 / zstw.1980.92.2.459 .

- Schultz: Homicides . Ed .: H. Göppinger, PH Bresser. Enke, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-432-91281-1 , p. 13 ff .

criminology

- Günther Bauer: Violent crime - A. Murder . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts (Hrsg.): Short dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. Volume IV (supplementary volume). de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1979, p. 81 ff .

- Steven Malby: Homicide . In: Stefan Harrendorf , Markku Heiskanen, Steven Malby, European Institute for Crime Prevention And Control, Affiliated With the United Nations (Eds.): International Statistics on Crime and Justice (= HEUNI Publication Series . No. 64 ). European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, 2010, ISBN 978-952-5333-78-7 , ISSN 1237-4741 ( heuni.fi ).

- Wolf Middendorf: negligent homicides . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts (Hrsg.): Short dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. tape V . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-016171-0 , p. 89-103 .

- Dirk Lange: The politically motivated killing. Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56656-5 .

- Wilfried Rasch : Homicides, non-negligent . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts , Hans Joachim Schneider (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. tape III . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1979, ISBN 3-11-008093-1 , p. 353-398 .

- Marvin E. Wolfgang , Margaret A. Zahn, Lloyd L. Weinreb: Homicide . In: Sanford H. Kadish (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice . 1st edition. Volume II (Criminalistics-human rights). Collier Macmillan, London / New York 1983, ISBN 0-02-918130-5 , pp. 849-865 .

psychology

- David Buss : The killer in us. Why we are programmed to kill. 2nd Edition. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8274-2083-1 . (Original: The Murderer Next Door. Why the Mind is designed to kill. Penguin Press, New York 2005, ISBN 1-59420-043-2 ).

- Heidi Möller : People who have killed, depth hermeneutic analyzes of killing delinquents . Opladen 1996, ISBN 3-531-12821-3 .

psychiatry

- Johann Glatzel: murder and manslaughter. Killing acts as relationship crimes. Heidelberg 1987, ISBN 3-7832-0386-4 .

Criminology

- Günther Dotzauer, Klaus Jarosch, Günter Berghaus: Homicides . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts , Hans Joachim Schneider (Hrsg.): Concise dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. tape III . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1979, ISBN 3-11-008093-1 , p. 398-421 .

Documentaries

- Blind spot: Murder by Women. A film by Irving Saraf, Allie Light and Julia Hilder, 2000.

- Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer. Directed by Nick Broomfield , 2003 Amnesty International Award-winning documentary.

Web links

- 2011 Global Study on Homicide. (PDF; 7.1 MB) Trends, Context, Data. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), accessed on November 14, 2011 (International Study of Homicides by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime ).

- UNODC Homicide Statistics. (PDF; 7.4 MB) UNODC , accessed on November 15, 2011 (English, page with data in Excel 2007 tables; cases of homicides, including gender-specific, firearms and in the most populous cities).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Federal law: 18 USC § 1111 (a)

- ^ Garner: Black's Law Dictionary . P. 1177.

- ↑ Bamidbar - Numbers - Chapter 35

- ^ A b Wolf Middendorf: Negligent homicides . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts (Hrsg.): Short dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. tape V . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1995, p. 89-103 .

- ^ Eberhard Schmidt : Introduction to the history of the German criminal justice system . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995, p. 31–33 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Sura 2: 178

- ↑ Sura 5:45

- ↑ Sura 4:92

- ↑ Pakistan Penal Code (Act XLV of 1860) as amended by Act No. II of 1997 (PDF): p. 300قتل عمد (deliberate killing), p. 315 قتل شبه عمد (quasi-deliberate killing), p. 318 قتل خطا (mistaken killing), p. 321 قتل بالسبب (Killing due to indirect cause)

- ↑ Islamic Criminal Code (قانون مجازات اسلامی) from 2013, Book 3 ( Qisās , Art. 217-447) and Book 4 ( Diyāt , Art. 448-727)

- ↑ Materials Swiss Criminal Code : Art. 52 Para. 2 VE 1896 (PDF)

- ↑ ss. 219, 220 Criminal Code (Canada)

- ^ A b c d e f Albin Eser , Hans-Georg Koch: The intentional killing offenses . In: Journal for the entire field of criminal law . tape 92 , 1980, pp. 494-507 .

- ↑ a b c d Günter Heine : Status and development of the murder facts: National and international . In: Sensitive and thinking criminal sciences : Gift of honor for Anne-Eva Brauneck . 1999, p. 315-352 .

- ↑ James Fitzjames Stephen : Digest of Criminal Law 8 . 1947, p. 295 ff .

- ↑ Daughdrill v State , 113 Alabama 7, 21 So. 378 (1896).

- ↑ Christian Köhler: Participation and omission in a successful offense using the example of bodily harm resulting in death (Section 227 I StGB) . Springer, 2000, p. 48 ff . ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Eberhard Schmidt : Introduction to the history of the German criminal justice system . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995, p. 172 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Homicide Act 1957, p. 1. Abolition of “constructive malice”

- ↑ R. v. Martineau , [1990] 2 SCR 633

- ↑ Reason: GP XIII RV 30 (PDF) p. 189 ff.

- ↑ BBl. 1985 II 1009 (PDF) 1020 ff.

- ↑ UNODC: 2011 Global Study on Homicide. Pp. 15-16, 87-88.

- ↑ nationmaster.com Seventh United Nations Survey of Crime Trends and Operations of Criminal Justice Systems, covering the period 1998–2000 (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Center for International Crime Prevention) viewed via NationMaster : February 18, 2010.

- ↑ United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime: Global Study on Homicide 2011.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wilfried Rasch : homicides, non-negligent . In: Alexander Elster [founder], Rudolf Sieverts (Hrsg.): Short dictionary of criminology . 2nd Edition. tape III . de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1979, p. 353-398 .