Danish language

| Danish (dansk) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

See also under "Official Status" in: Canada , Argentina , United States , Sweden |

|

| speaker | 5.3 million (native speakers) 0.3 million (second language speakers) |

|

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in |

|

|

| Recognized minority / regional language in |

|

|

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

there |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

Dan |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

Dan |

|

The Danish language (Danish dansk sprog, det danske sprog ), briefly Danish (dansk), belongs to the Germanic languages and there to the group of Scandinavian (North Germanic) languages . Together with Swedish , it forms the East Scandinavian branch.

Danish sole national language of is Denmark and the Empire Danish (rigsdansk) standardized. The language code is there or dan (according to ISO 639 ).

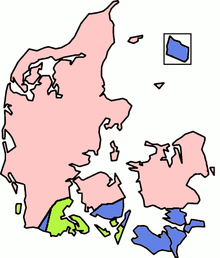

distribution

In Denmark, Danish is spoken by around 5 million native speakers. Other native speakers are mainly from Greenland and the Faroe Islands (both politically part of Denmark), South Schleswig ( Germany ), Iceland , Norway and Sweden , as well as Argentina , Canada and the USA , e.g. B. in Solvang, California .

In the earlier Danish colonies in the West and East Indies and on the Gold Coast , Danish never had more than marginal status; Certain place and fortress names in Danish have been preserved there to this day.

status

Danish is de facto the official language in Denmark , without this being legally recorded anywhere. It is the second official language in Greenland (next to Greenlandic ) and on the Faroe Islands (next to Faroese ). It is taught as a compulsory subject in Iceland , but lost its status as the first foreign language to English in 1990 . In southern Schleswig it has the status of a regional and minority language .

Danish has been the official EU language since 1973, when Denmark joined the EU .

South Schleswig is located in northern Germany, right on the German-Danish border . The region north of the Eckernförde - Husum line was populated by Danish people after the migration of peoples (and the departure of a large part of the fishing rods who had previously settled there ). Until the language change in the 19th century, Danish varieties such as Angel Danish were still widespread. Politically, the region initially belonged directly to Denmark , with the establishment of the Duchy of Schleswig as a fiefdom , and after the German-Danish War in 1864, South Schleswig finally came to Prussia / Germany. Today around 50,000 Danish people from southern Schleswig live as a recognized national minority in the region. Around 8,000–10,000 of them speak Danish in everyday life and 20,000 speak Danish as their mother tongue. Many Danish people from South Schleswig now speak a North German-colored Standard Danish (Rigsdansk), which is referred to as South Schleswig-Danish (Sydslesvigdansk) . The dialect Sønderjysk (South Jutland) is sometimes also spoken near the border . In the Flensburg area, a German-Danish mixed language developed with the Petuh . The Schleswig Low German spoken in the region still has Danish substrate influences to this day. The North Frisian dialects widespread on the North Sea coast of South Schleswig are also partly influenced by Danish. Analogous to the Danish ethnic group in South Schleswig live north of the border between 12,000 and 20,000 German North Schleswig residents, who are accordingly recognized as a national minority in Denmark. About 2/3 of them speak Danish as an everyday language, but German is still a cultural language. Analogous to southern Schleswig-Danish, a German variety influenced by the surrounding Danish language has developed in the German minority, which is known as northern Schleswig-German.

Danish is particularly protected in Schleswig-Holstein by its state constitution . There are Danish lessons in both Danish and, occasionally, in public German schools, especially in the Schleswig region. Since 2008 there have been bilingual place-name signs in Flensburg and since 2016 in Glücksburg (Danish Flensborg and Lyksborg ).

Although it is heavily influenced by Low German in terms of vocabulary , the linguistic boundary to the German dialects is not a fluid one, but a hard one (see, on the other hand, the language boundary between German and Dutch ). Historically, it ran on the same line as Eider - Treene - Eckernförde . Since the High Middle Ages (approx. 1050 to 1250), however, the German language also became increasingly popular north of the Eider.

Scandinavian , which is widespread in Skåne , developed out of a Danish dialect and can now be classified from a linguistic point of view as both a southern Swedish and an eastern Danish dialect. Gotlandic (Gutamål), which is still widespread on the island of Gotland , also has Danish influences (due to the island's long membership of Denmark). In addition to archaic Nordic forms, there are also many loanwords from the Danish era. Corresponding examples are någle (Danish nogle , Swedish några , German some ), saktens (Danish says , Swedish nog visst , German easy ) or um en trent (Danish omtrent , Swedish approx . , German approximately, about ).

In some cases, today's Scandinavian written languages are closer to each other than the most strongly deviating dialects of the respective country; on the other hand, there are also specific Danish, Swedish and Norwegian language characteristics. The dialect boundaries between the languages represent smooth transitions, one speaks of a dialect continuum Danish-Norwegian-Swedish.

However, from political and cultural tradition, three independent languages were retained. The decisive factor for this is that Denmark and Sweden developed their own standardized written languages by the 16th century at the latest. In Norway, this only happened with independence in the 19th century and led to two written languages, because the educated class kept Danish as the standard language until then.

Danish, Norwegian and Swedish

The Bokmål variant of Norwegian is linguistically a Danish dialect with Norwegian influences. In terms of cultural history, however, it is regarded as one of the two official Norwegian written languages and is also clearly perceived as Norwegian by its users. The supporters of the Nynorsk , which is based on the dialects, have, however, often polemicized against this "Danish" language of the urban population and upper class.

From the linguist Max Weinreich the saying "A language is a dialect with an army and a navy" is passed down, which also applies to Scandinavia . Linguistically, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian could be considered dialects of the same language, since the languages are still mutually understandable. Of course, there is no official umbrella language that could take the place of standard Scandinavian. One of the three individual languages is always used for inter-Scandinavian communication. Everyone speaks “Scandinavian” in their own way.

Danish, Swedish and Norwegian make up the group of mainland Scandinavian languages. Unlike Danish and Swedish, Norwegian is a western Nordic language. All three developed from the common Norse language; It was also important that the Scandinavian countries always had close political, cultural and economic ties through the centuries and also largely adopted the same loanwords, especially from Low German and later High German . The "continental" Scandinavia stood in contrast to the island Scandinavian on the Faroe Islands and Iceland, which has retained an ancient ( Old Norse ) character.

It is estimated that the vocabulary matches between Danish and Norwegian (Bokmål) are over 95%, and between Danish and Swedish around 85–90%. The factual communication in the spoken language can depend on the familiarization. Recently, Scandinavians have also spoken in English. The written language is largely mutually understandable, so that non-Scandinavians with a knowledge of Danish can understand Norwegian and Swedish texts (and vice versa).

The East Scandinavian or Swedish-Danish branch is mainly distinguished from the West Scandinavian languages (Icelandic, Faroese, Norwegian) by the so-called East Scandinavian monophthonging (from 800).

- urnordian / ai / becomes Old Norse / ei / and further to East Scandinavian / eː /

- Old Norse / Icelandic Steinn, Norwegian Stein → Danish and Swedish sten 'Stein'

- Old Norse breiðr, Icelandic breiður, Norwegian brei → Danish and Swedish bred 'broad'

- / au / becomes / øː /

- Old Norse rauðr, Icelandic rauður, Norwegian raud → Swedish röd or Danish rød 'red'

- urnordian / au / with i-umlaut becomes Old Norse / ey /, Norwegian / øy / and further to East Scandinavian / ø /

- Old Norse / Icelandic ey, Norwegian øy → Swedish ö or Danish ø 'island'

Around 1200 Danish has both by the Association of Ostskandinavischen as removed from that of the West Nordic by the plosives / p, t, k / after a vowel to / b, d, g / lenited and the related unstressed position vowels / a, i, o ~ u / have been weakened to the murmur / ǝ /. The previous east-west divorce in Scandinavia was thus overlaid by a new north-south grouping. The comparison of Swedish and Danish shows this difference to this day:

- Swedish köpa versus Danish købe 'buy', Swedish bita versus Danish bide 'bite', Swedish ryka versus Danish ryge 'smoke'.

Dialects, sociolects and mixed languages

Dialects

Danish is divided into three main dialects:

-

Jutish (jysk) or West Danish (vestdansk) or mainland Danish in Jutland

- South Jutian (sønderjysk) in Sønderjylland ( North Schleswig and parts of South Schleswig )

- West Jutish (vestjysk) on the west coast (e.g. Esbjerg )

- East Jutian (østjysk) on the east coast (e.g. Aarhus )

- Danish island (ødansk) on Fyn , Zealand (with the Copenhagen dialect Københavnsk ) Ærø , Langeland , Lolland , Falster and Mon.

- Ostdänisch (Østdansk) to Bornholm ( Bornholmsk dialect ) and in Skåne , Halland and Blekinge ( Scanian has increasingly since the 1658 Swedish customized)

The dialects spoken on the Baltic island of Bornholm and in Jutland are difficult to understand for non-native speakers. From a Danish point of view, Scandinavian is interpreted as an East Danish, and from a Swedish point of view as a South Swedish dialect.

The southern Schleswig-Danish spoken by many Danish people from southern Schleswig-Holstein is a variant of Imperial Danish strongly influenced by North German, whose linguistic classification as a mere variety, dialect or contact language has not yet been completed.

Sociolects

The traditional dialects have increasingly been displaced by the standard language in recent decades. Urban sociolects have emerged in the larger cities (e.g. vulgar Copenhagen ), which also spread to the countryside. The social differentiation of Danish has taken place particularly since the second half of the 20th century. The pronunciation varieties of different social classes and generations are more pronounced in Danish than in most other Germanic languages; only English is comparable here.

Mixed languages

The Petuh in Flensburg is related to Danish . Petuh, also known as Petuh-Tanten-Deutsch , is partly based on Danish grammar (sentence structure) and contains a number of Danisms , but its vocabulary is very similar to High and Low German, so that it is more likely to be assigned to the latter. It dates from the 19th century and can be understood as an attempt by Danes to speak German. The Schleswigsche in fishing , that there the former Angel Danish has displaced is also characterized by Danismen and differs from the southern Low German dialects from; the language change did not take place here until the 19th century.

In addition, there was Creole Danish in the Danish West Indies until the 20th century , but it is no longer spoken by anyone and has not survived in writing.

Written language

The Danish orthography is based on the medieval Zeeland dialect. At that time it was the central dialect of Denmark, as Scania was also part of the empire. The pronunciation of the upper class in Copenhagen is setting the tone today. The Danish spelling is relatively conservative, which means that many former sounds that have become mute in the course of language history are still written - or even inserted in an analogous way where they are historically unjustified. Examples are:

- the <h> before <v> and <j>, which can only be heard in the North Jutian dialect and is a holdover from the Old Norse language level, for example hvid [viðˀ] 'white' (Old Norse hvít ), hjul [juːˀl] 'Rad '(Old Norse hjúl ).

- the <d> in connections like <ld>, <nd>, <rd>, which also reflects a historical sound, but is also partly an analogical spelling, for example (etymologically based) in land [lænˀ] 'Land' (Old Norse land ), (introduced analogously) in fuld [fʊlˀ] 'full' (Old Norse fullr ).

There are also some characteristics of vocalism that are not expressed in Scripture:

- the lowered short / e / in words like fisk [fesg] 'fish' and til [te (l)] 'zu'

- the lowered short / o / in hugge [hogə] ‚hauen, hacken ', tung [toŋ]‚ heavy'

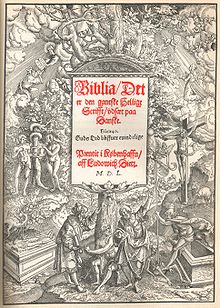

The first Danish translation of the New Testament , the so-called Christian II's Bible , appeared in 1524. It still suffered from numerous orthographic problems. The first Danish full Bible did not appear until 1550.

Danistics and Danish lessons in Germany

Danistik is the Danish philology . In practice it is always practiced in connection with the other Scandinavian languages as Scandinavian Studies (also: Nordic Studies). Larger institutes for Scandinavian studies are located in Berlin , Greifswald and Kiel .

In South Schleswig there are a number of Danish schools that are intended for the Danish minority . Since they have been visited by children of German native speakers for over 60 years, which is possible if the parents also learn Danish (parents' evenings are usually held in Danish), Danish native speakers are now in the minority here. For this reason, the question within the minority is disputed whether the success of the Danish school system beyond the core group is desirable or whether it tends to lead to a dilution of identity. However, since the principle of free confession applies to membership of the minority, no ethnic criteria can be established.

The best- known and most traditional Danish school in Germany is the Duborg-Skolen in Flensburg , which until 2008 was the only Danish grammar school in Germany . With the AP Møller-Skolen , another Danish high school was opened on September 1, 2008 in Schleswig ; It is a gift worth € 40 million from the Copenhagen shipping company Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller to the Danish minority in Germany.

In Schleswig-Holstein there are also individual public German schools where Danish lessons are offered as a foreign language.

Danisms

As Danismus a Danish language or meaning is called, in a different language has been incorporated.

In the Middle Ages, Danish exerted a strong influence on Old English and thus on modern English , as parts of the Anglo-Saxon East of England ( Danelag ) had been occupied by the Great Pagan Army from Denmark, among others , and were subsequently settled permanently; genetically, they can hardly be distinguished from the Norwegian loanwords. In today's English, the Scandinavian loan word and the hereditary word inherited from Old English are often next to each other, whereby the hereditary word is limited in meaning or otherwise specialized. Examples are: Danish. dø ‚die '→ engl. die (besides: starve , die hungers , starve '), old Danish. take (or new dan. days ) 'take' → engl. take (next to it: nim 'steal, steal'; numb 'dazed, numb, from the finger'), dan. box 'throw' → engl. cast (next to it: warp 'throw, warp, from wood'), dan. sky 'cloud' → engl. sky 'heaven', obsolete 'cloud' (next to it: heaven 'heaven in the religious sense').

Faroese is a language that is significantly influenced by Danisms , although many of the words perceived as Danisms are loan words from German or Low German (see Faroese language policy ).

Norwegian has been heavily influenced by Danish due to the country's centuries of political ties with Denmark. The Bokmål variant is therefore a standard variant that tries to combine the Norwegian and Danish heritage, whereas Nynorsk is based on the autochthonous Norwegian dialects.

Foreign language influences on Danish

The influence of German is particularly significant , especially (and mediated by the geographical proximity and trade) of Low German in the late Middle Ages and early modern times. A large part of the Danish vocabulary (25%) consists of Low German loan words and loan translations. In addition, Standard German was the language at the Danish court until the 19th century and was therefore considered elegant, similar to French at the Prussian court , which also encouraged the adoption of German terms.

In today's Danish there are - as in German - a large number of so-called internationalisms ( anglicisms have increased in recent decades ).

Nevertheless, Danish is a Scandinavian language, so there is a hard language border to Standard German. This other origin distinguishes it more from German in the genesis and structure of the language than, for example, English , which, like German, is of West Germanic origin. If, however, there is often a greater similarity between German and Danish than with English, especially in the area of vocabulary, this is due to secondary reasons alone, namely on the one hand the aforementioned Low and High German influence on Danish and on the other hand the strong influence of English during the Middle Ages through French.

The Danish alphabet

The Danish alphabet includes all 26 standard letters of the Latin alphabet . The letters C, Q, W, X, and Z occur only in foreign words, although they have been partially replaced:

- center , center ', censur , censorship', charmerende , charming ' chokolade , chocolate', computer , computer ' cølibat , celibacy'.

- quasi, quiz, but: kvalitet 'quality', kvotient 'quotient'

- walisisk , Welsh ', whiskey, Wikipedia

- xylophone , xylophone ', saxophone , saxophone,' but: sakser , axis'

- tsar, zebra, zenith, zone, zulu, but: dominans, consecutive .

There are three special characters:

- Æ , æ : Typographically , the Æ is a ligature from A and E. It corresponds to the German Ä.

- Ø , ø : From a graphic point of view, Ø was originally a ligature of O and E. It corresponds to the German Ö.

- Å , å : The Å (also called "bolle-Å", which means something like "Kringel-Å") was introduced with the Danish spelling reform of 1948 . It replaces the older double-A (Aa, aa), which is only used for proper names and on "ancient" lettering, but no longer in the other written language . Since 1984,however, place names can be spelled with Aa again, and some places expressly want this old spelling ( see Aabenraa ). In terms of the history of graphics, the ring on Å is a small O, which indicates that it was originally a (long) A-sound, which in the course of language history - as in many Germanic languages and most German dialects - in the direction of O has evaporated. The city of Ålborg z. B. is thus pronounced like "Ollbor". Incidentally, Danish does not have any doubling of vowels in writing, but it does with consonants .

These three special letters are at the end of the alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U , V, W, X, Y, Z, Æ, Ø, Å (Aa).

In German typesetting , these three letters should never be circumscribed with Ä, Ö, and Aa in Danish names, keywords and quotations or even in Danish use (although Danes could still decipher it). The same applies to the Internet, with the exception of domains , although in the latter case the legend is not always clear: for example, the singer Stig Møller is represented on the WWW at stigm oe ller.dk , while the singer Lis Sørensen at the address liss o rensen .dk can be found. Other exceptions outside of the Internet are only personal names such as B. Kierkegaard , this is about preserving the old spelling. In the past, Ø and ø were often replaced by Ó and ó in the handwriting . Today you see this a little less often, but it's all about the script used. Until 1875, the Gothic script , called skrift gotisk , gothic font used ', then the skråskrift, until it gradually at the end of the 20th century by the formskrift (1952 by Norwegian submission of Alvhild Bjerkenes by Christian Clemens Hansen in Denmark introduced) almost was replaced . As cursive a Danish version which was in the 19th century German cursive script used later on the Latin script .

| Letter | Windows | HTML |

|---|---|---|

| Æ | Alt + 146 |

Æ

|

| æ | Alt + 145 |

æ

|

| O | Alt + 157 |

Ø

|

| O | Alt + 155 |

ø

|

| Å | Alt + 143 |

Å

|

| å | Alt + 134 |

å

|

For computer users, there are numerous resources that make it easier to use Danish (and other types of) special letters and accents. For example, under GNU / Linux and Mac OS X, a keyboard variant can be selected that can add various special characters to the actual layout. Alternatively, you can also use character tables (e.g. kcharselect , charmap.exe etc.).

On many UNIX systems you can also use these characters with " Compose " + "a" + "e", " Compose " + "/" + "o", " Compose " + "o" + "a" and " Compose " + Enter "*" + "a".

Under Mac OS X you can create special characters with the help of the option key "alt": alt + a for å, alt + o for ø and alt + ä for æ. The Danish capital letters are obtained by using the German capital letters.

Under Windows , the characters can be entered by pressing the Alt key and entering the character codes from code page 850 (see adjacent table) on the numeric keypad of the keyboard. The HTML codes for the special characters are also given in the table below.

Phonology

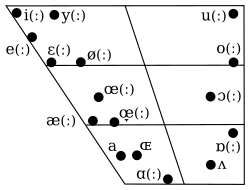

Vowels

Danish has 15 short and 12 long monophthongs .

| front | central | back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| closed | iː | i | yː | y | uː | u | ||

| half closed | eː | e | O | O | O | O | ||

| medium | ə 1 | |||||||

| half open | ɛː | ɛ | œː | œ | ʌ | ɔː | ɔ | |

| open | æː 2 | a | ɶː | ɶ | ɑː | ɑ | ɒː | ɒ |

- The schwa [ ə ] is the unstressed vowel. Example: mile [ˈmiːlə] .

- The almost open vowel / a / is the long counterpart to open vowel / a / .

Allocation letter - sound:

- a ɑ ; ɑː

- e e ; eː ; ə ; ʌ

- i i ; iː

- o o ; O

- u u ; uː

- y y ; yː

- æ a ; æː ; ɛ ; ɛː

- ø ɶ ; ɶː ; œ ; œː ; ø ; O

- å ɒ ; ɒː ; ɔ ; ɔː

Danish has 25 diphthongs :

- [e: ɪ> e:] (eg, webs), [ɛ: ɪ> ɛ:] (læge), [æ: ɪ> æ:] (bag, hage), [ɑ (:) ɪ] (leg, maj), [u (:) ɪ] (huje), [ʌ (:) ɪ] (løg, øje)

- [i (:) ʊ] (liv, blive), [e (:) ʊ] (blev, leve), [ɛ (:) ʊ] (bæve, hævne), [æ (:) ʊ] (lav), [a (:) ʊ] (hav, brage), [y (:) ʊ] (lyve), [ø (:) ʊ] (løve), [œʊ] (neuter), [ɔ (:) ʊ] ( lov, sove), [ʌ (:) ʊ] (låge, love)

- [i (:) ʌ] (Birte, fire), [e (:) ʌ] (flertal, mere), [ɛ (:) ʌ] (lærte, lære), [æ (:) ʌ] (verden, værre ), [y (:) ʌ] (hyrde, hyre), [ø (:) ʌ] (hørte, høre), [œ (:) ʌ] (gørtler, gøre), [u (:) ʌ] (urmager , ure), [o (:) ʌ] (spurgte, bore)

Alternatively, they can be analyzed as consisting of a vowel and / j ʋ r / .

Consonants

Danish has 17 consonants .

| bilabial |

labio- dental |

alveolar | palatal | velar | uvular | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | pʰ b̥ | tˢ d̥ | kʰ g̊ | ||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Fricatives | f v | s z | H | ||||

| Approximants | ʋ | ð | j | ʁ | |||

| Lateral | l |

Allocation letter - sound:

- b b̥

- d ð

- f f ; final: v

- g g̊

- h h

- y y

- k kʰ

- l l

- m m

- n n ; before g and k : ŋ

- p pʰ

- r ʁ

- s s ; in the final: z

- t d̥ ; Initially : tˢ

- v ʋ

The following strings have their own pronunciation:

Source: Hans Basbøll, The phonology of Danish, Oxford 2005.

pronunciation

The burst sound (Stød)

The Stød ['sd̥øð] is a laryngealization that accompanies long vowels and certain consonants. Today there are no longer any uniform rules for where and when the Stød is used; originally the Stød was a feature in the set of stressed monosyllabic words with a long vowel or with voiced consonants in the final. This is not only a question of the dialect , but also of the sociolect , whereby the upper classes use the Stød more often and that it is absent in the south of the entire language area. In addition, there are some cases in which identical words experience a difference in meaning due to the stød, e.g. B. ['ænən] ' other '~ [' ænˀən] 'the duck', ['ånən] ' breathing '~ [' ånˀən] 'the spirit', ['hεnɐ]' happens' ~ ['hɛnˀɐ]' Hands'.

In its Scandinavian relatives, Swedish and Norwegian, the Danish Stød has its equivalent in the “simple” musical accent 1, which originally only appeared in monosyllabic words. See also: Accents in the Scandinavian languages .

Vowel qualities

The Danish vowels are similar to the German ones, but some are not identical. Basically, all vowels before or after the / r / (which is spoken uvularly or vocalized) are more open. The / a / is pronounced lighter (similar to English). The Å is pronounced short and in the position after r like the German o in Torte; otherwise roughly like in French chose .

Mute consonants

If it is complained that Danish is nowhere near as spoken as it is written, this is largely not only due to the soft D (which is softer than the English th in that ), but also to the fact that various historical consonants have become mute or, to put it the other way round: that consonants that have not been spoken for a long time are still being written.

This mostly affects / d /, / g /, / t / and other consonants in the final or in the interior of the word . For example det 'das' is not pronounced [det], but always [de]. Also z. B. the pronouns mig 'me' and dig 'you' are spoken differently than written: ['mai] and [' dai]. Not all of these mute consonants known to Scripture are etymologically justified; for example, the / d / was originally spoken in find (cf. German Find ), whereas in mand it represents a purely analogical spelling (cf. German Mann ).

-he end turns into a vowel like in German, e.g. hammer = ['hamɐ] (similar to the German hammer ).

A well-known song chorus is used to illustrate the diphthong formation of [ei]:

En snegl på vejen er tegn på regn i Spain

[en ˈsnɑɪˀl pʰɔ ˈʋɑɪˀɪn æɐ ˈtˢɑɪˀn pʰɔ ˈʁɑɪˀn i ˈsb̥ænjən]

A snail on the way is a sign of rain in Spain

(From: My Fair Lady , the Danish version of: It's so green when Spain's flowers bloom )

Phonetic equivalents

Some rules can be set up (with a few exceptions).

| Urgermanic | German | Danish | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consonants | |||

| * p | pf-, -ff- (-pf-) | p-, -b- (-pp-) | Pfeffer = peber (b is pronounced like German w), stuff = stop |

| * b | b | b-, -v- | Beaver = bæver |

| * f | v, f | f | Father = fa (de) r |

| * t | z-, -ß- (-tz-) | t-, -d- (-tt-) | two = to, sat = sad, set = sætte |

| * d | t | d | tot = død |

| * þ- | d | t, -d- | Thing = ting, brother = bro (de) r |

| * k | k-, -ch- (-ck-) | k-, -g- (-kk-) | can = kunne, roof = day |

| * sk | sch | sk | Bowl = skål |

| *G | G | g-, -g / v / j- | good = god, to fly = flyve (prät. fløj) |

| Vowels | |||

| * a | a | a, å, o | other = anden, band = bånd, hold = lovely |

| * a ( i-umlaut ) | e, Ä | e, æ | Men = mænd, better = depre |

| * e | self = selv | ||

| * e ( a-umlaut ) | je, yeah | Heart = hjerte | |

| * e ( u-umlaut ) | jo, jø | Earth = jord, bear = bjørn | |

| * ē 1 | a | å | Measure = måde |

| * ē 1 (i-umlaut) | uh | æ | |

| *O | uh | O | Cow = ko |

| * ō (i-umlaut) | uh | O | Cows = køer |

| * au (before r, h) | Oh | Ear = øre | |

| * ouch | ouch | Eye = ø each | |

| * ū | u | House = hus | |

| * u | u | Customer = customer | |

| * u (a-umlaut) | O | u. O | Vogel = fugl, horn = horn |

| * u (i-umlaut) | ü | y | Sin = synd |

| * ū (i-umlaut) | eu, eu | extremely = yderst | |

| * eu (i-umlaut) | eu | interpret = tyde | |

| * eu | ie | to fly = flyve | |

| ē 2 | e, æ | here = here, knee = knæ | |

| * ai | egg | e | Stone = sten |

| * ī | i | Ice = is | |

| * i | i | find = find | |

Modern standard grammar

The noun

Grammatical genders

The standard Danish language has two grammatical genders, the neuter and the uttrum . In the Utrum, the original Indo-European genera masculine and feminine have merged.

Flexion

With the exception of the genitive, Danish has no case inflection in nouns. The genitive is uniformly formed by adding the ending -s : Fars / mors / barnets has 'the hat of the father, the mother, the child'

There are several options for forming the plural:

- In most cases, the plural is formed by adding -er or (if the singular ends in a vowel) -r , e.g. E.g .: køkken 'kitchen' → køkkener 'kitchens'; værelse 'room' → værelser 'room, pl.'

- 15 words have umlaut in the plural ; the three types are nat 'night' → nætter 'nights'; hånd 'hand' → hænder 'hands', bent 'book' → bøger 'books'

- The second most common plural formation is to add -e : bord , table '→ borde

- Four words have umlaut in the plural: fa (de) r 'father' → fædre 'father'; bro (de) r 'brother' → brødre 'brothers'; mo (de) r 'mother' → mødre 'mothers'; datter 'daughter' → døtre 'daughters'

- A small group of nouns in the plural has no ending: tog 'Zug' → tog 'Zug '

- Three words have umlaut in the plural: mand 'man' → mænd 'men'; gås 'goose' → gæs 'geese'; barn 'child' → børn 'children'

- A plural formation that only occurs lexically today knows øje 'eye' → øjne 'eyes'

- Certain foreign words retain the plural from the original language: check 'Check' → checks 'Checks'; faktum 'fact' → fakta 'facts'

Certainty

Danish has two indefinite articles :

- en for the utrum (fælleskøn) and

- et for the neuter (intetkøn)

Examples:

- mand 'man' → en mand 'a man'

- kvinde 'woman' → en kvinde 'a woman'

- barn 'child' → et barn 'a child'

To distinguish that there is one child and not two, one can put an accent: ét barn - to børn ' one child' - 'two children'.

Simple definiteness is expressed by a suffixed (appended, i.e. not prefixed as in German) article. Danish has this in common with all Scandinavian languages:

- - (e) n for Utrum Singular

- - (e) t for neuter singular

- - (e) ne for the plural

Examples:

- mand 'man' → manden 'the man'; kvinde 'woman' → kvinden 'the woman'; opera 'opera' → operaen 'the opera'; hus 'house' → huset 'the house', værelse 'room' → værelset 'the room'

- mænd 'men' → mændene 'the men'; kvinder 'women' → kvinderne 'the women'; huse 'houses' → husene 'the houses'; tog 'trains' → togene 'the trains'; værelser 'room (pl.)' → værelserne 'the room'

If the stem vowel is short, the final consonant has to be doubled: rum 'space' → rummet 'the space' or rummene 'the spaces'.

If an adjective is added, the certainty is expressed as in German by a preceding definite article:

- de in the plural

- the one in the Utrum singular

- det in the neuter singular

Unlike in Swedish and Norwegian, there is no double article setting - the article is not appended if it is placed in front:

- de to brødre 'the two brothers'

- the store kunstner 'the great artist'

- det røde billede 'the red picture'

There are also some special cases such as

- hele dagen 'all day'

The adjective

Flexion of the positive

Like all Germanic languages apart from English, Danish also has a definite and an indefinite inflection. The definite form is independent of gender and number -e , the indefinite form is in the singular uttrum zero ending, in the neuter -t and in the plural -e :

- definite: den store mand 'the big man', det store barn 'the big child', de store mænd, børn 'the big men, children'

- indefinitely: en stor mand 'a great man', et stort barn 'a great child', store mænd, børn 'great men, children'

In the case of polysyllabic adjectives, -l, -n, -r and unstressed -e- are omitted:

- en gammel mand 'an old man', gamle mænd 'old men'

Exceptions:

- Adjectives that end in unstressed -e (this also includes the comparative and present participle) and unstressed -a are not inflected: ægte 'real' → ægte, ægte . Further examples in the indefinite neuter: et lille barn 'a small child', et moderne hus 'a modern house'; et lilla tørklæde 'a purple headscarf'

- Adjectives that end in stressed -u and -y as well as unstressed -es are not inflected: snu , smart '→ snu, snu; sky 'shy' → sky, sky; fælles 'common' → fælles, fælles . Examples: et snu barn 'a clever child'; et fælles attached 'a common concern'; sky fugle 'shy birds'.

- Adjectives that end in a stressed -å have a neuter form, but no specific plural ending: blå , blue '→ blåt, blå . Example: et blåt øje 'a blue eye', blå øjne 'blue eyes'

- Two-syllable adjectives that end in an unstressed -ed have the e-form, but not an indefinite neuter form: foreign med , foreign '→ foreign med , foreign mede . Example: et Fremdmed menneske 'a strange person', Fremdmede mennesker 'strange people'

- Adjectives in -sk do not have an indefinite neuter form if it is an adjective for a geographical area: dansk 'Danish' → dansk, danske; other adjectives in -sk can optionally have a -t in the neuter.

- ny 'new' and fri 'free' know forms with and without -e : ny → nyt, nye / ny; fri → frit, frie / fri

- the plural of lille 'small' is små: et lille barn 'a small child' → små børn 'small children'

Unlike in German, but as in all Scandinavian languages, the adjective is also inflected in the predicative position:

- Manden er stor, barnet er stort, børn er store 'the man is big, the child is big, the children are big'

increase

The comparative is usually expressed by -ere , the superlative by -est :

- ny 'new' → nyere 'newer', nyest 'new (e) st'

The comparative shows no further inflection forms, the superlative knows zero ending and -e .

A small number of adjectives knows in comparative and superlative umlaut plus the ending -re :

- få 'little' → færre, færrest

- lang 'lang' → længre, længst

- stor 'big' → større, størst

- ung 'young' → yngre, yngst

Some adjectives change the word stem, whereby umlaut can also occur here:

- dårlig 'bad', ond 'bad' → værre, værst

- gammel 'old' → ældre, ældst

- god 'good' → bedre, bedst

- lille / lidt 'small' → mindre, minst

- mange , much → ' flere, Flest

Are then irregular

- megen / meget 'a lot' → mere, mest

- nær 'near' → nærmere, nærmest

Most three- and multi-syllable adjectives as well as foreign words and participles can also be increased with mere and mest : intelligent → mere intelligent, mest intelligent

The pronouns

Personal pronouns

The personal pronouns almost all have their own object form:

- any 'I' → mig 'me, me'

- you 'you' → dig 'you, you'

- han 'he' (personal) → ham 'him, him'

- hun , they '(personal) → rising , your,'

- the 'he, she, it' (impersonal) → the 'him, him, it, her, she'

- det 'it' (personal); 'He, she, it' (impersonal) → det 'him, it'; 'Him, him, it, her, she'

- vi 'we' → os 'us'

- I 'you' → jer 'you'

- de 'they' → the 'they, them'

The 2nd person plural I is always capitalized in the nominative, the 3rd person plural in the nominative and objective when it functions as a politeness form De, Dem .

possessive pronouns

Some of the possessive pronouns have an inflection according to gender (utrum, neutrum) and number (singular, plural):

- jed → min (utrum sg.), with (neuter sg.), mine (pl.)

- you → din, dit, dine

- han → hans (if related to another person) or sin, sit, sine (if reflexive)

- hun → hendes or sin, sit, sine

- den → dens or sin, sit, sine

- det → dets or sin, sit, sine

- vi → vores or (more formal) vor, vor, vor

- I → jeres

- de → deres

In the 3rd person plural, De, Deres are capitalized when they act as forms of courtesy.

The numerals

Basic numbers

The numbers are represented from 0 to 12 using separate words, those from 13 to 19 as a combination of the partially changed units digit and thes for 10:

0 nul, 1 en (utrum), et (neutrum), 2 to, 3 tre, 4 fire, 5 fem, 6 seks, 7 syv, 8 otte, 9 ni, 10 ti, 11 elleve, 12 tolv,

13 kick, 14 fjorten, 15 femten, 16 seksten, 17 sytten, 18 atten, 19 nitten

The decimal numbers are multiples of 10:

20 tyve, 30 tredive (or tredve ), 40 fyrre .

In addition to fyrre, there is the older long form fyrretyve, sometimes still used in emphasis , actually 'four tens'.

From the number 50 the decimal numbers follow the vigesimal system , i.e. That is, they are based on multiples of 20:

- 50 = halvtreds, shortened form of halvtredsindstyve, means halvtredje sinde tyve 'half-third times 20'

- 60 = tres, shortened form of tresindstyve, means tre sinde tyve '3 times 20'

- 70 = halvfjerds, shortened form of halvfjerdsindstyve, means halvfjerde sinde tyve 'half-fourth times 20'

- 80 = firs, shortened form of firsindstyve, means fire sinde tyve '4 times 20'

- 90 = halvfems, shortened form of halvfemsindstyve, means halvfemte sinde tyve 'half-fifth times 20'

In addition to this specifically Danish counting method, the common Nordic type “simple number + tens” is also represented in banking:

20 toti (literally: 'two tens'), 30 treti, 40 firti, 50 femti, 60 seksti, 70 syvti, 80 otti, 90 niti

This number system is not a borrowing from Swedish, as is often assumed, but was already known in Old Danish. With the introduction of the decimal currency in Denmark in 1875, it was revived for trade, but no longer gained wide use. The “FEMTI KRONER” on the 50 kroner note was therefore given up again in 2009.

Independent words are finally again:

100 hundrede, 1000 tusinde (or tusind ), 1,000,000 en million, 1,000,000,000 en billion, 1,000,000,000,000 en billion

One thing in common with German is that the units digit is pronounced before the tens digit. For example, the number 21 is pronounced as enogtyve ( en ' ein ', og 'und', tyve 'twenty'), the number 32 as toogtredive ( to 'two', og 'und', tredive 'thirty'), the number 53 as treoghalvtreds, 67 as syvogtres, 89 as niogfirs, 95 as femoghalvfems . If, on the other hand, the banking numbers are used, the English or Swedish word sequence applies; 21 is then called totien .

The hundreds are formed by the corresponding number word from 1 to 9 plus hundrede : 100 et hundrede, 300 tre hundrede . If tens and / or units are used, the numeric word is written together: 754 syvhundredefireoghalvtreds .

Ordinal numbers

The ordinal numbers of 1 and 2 are quite irregular: første , first (r / s) ', Andes , second (r / s)'. As in all Germanic languages, the others are formed by adding a dental suffix (in Danish -t, -d; followed by the ending -e ), whereby numerous smaller and larger irregularities occur:

1. første, 2. anden (utrum ), andet (neuter), 3. tredje, 4. fjerde, 5. femte, 6. sjette, 7. syvende, 8. ottende, 9. niende, 10. tiende,

11. ellevte or elvte, 12. tolvte, 13 . trettende, 14 fjortende, 15 femtende, 16 sekstende, 17 syttende, 18 attende, 19 nittende,

20 tyvende, 30 trevide or trevde .

The ordinal number of 40 is formed from the long form fyrretyve (see above) and reads fyrretyvende .

For 50 to 90 the ordinal number is formed from the long form of the vigesimal system; see. above:

50. halvtredsindstyvende, 60. tresindstyvende, 70. halvfjerdsindstyvende, 80. firsindstyvende, 90. halvfemsindstyvende .

The ordinal numbers of hundrede and tusinde remain unchanged: 100th hundrede, 1000th tusinde . The (rarely used) ordinal numbers of million, billion, billion are formed with -te : millionte, billionte, billionte .

Quantities

- et dusin 'a dozen, 12 pieces'

- en snes '20 pieces'

- et gros 'a gros, 144 pieces'

The verb

infinitive

The Danish verb ends in the infinitive with -e , which is omitted in the stem-closing vowel:

come ' to come', tro ' to believe'.

person

Unlike in German, there is no inflection according to persons in Danish, but only a uniform form. The present ending is consistently -er (or -r for the verbs ending in a stem-ending vowel ), the past ending for the weak verbs is -ede or -te , for the strong verbs the zero ending applies:

- Any kommer, du kommer, han / hun / det kommer, vi kommer, I kommer, de kommer 'I'm coming, you are coming, he / she / it is coming, we are coming, you are coming, they are coming' or everybody tror 'I believe 'etc.

- Any lavede, du lavede, han / hun / det lavede, vi lavede, I lavede, de lavede 'I made' etc.

- Anyone sang, you sang, han / hun / det sang, vi sang, I sang, de sang 'I sang' etc.

A few verbs have an irregular ending in the present tense, see below.

In the older literature there are still plural forms that end in -e ; their use was compulsory in the written language until 1900:

(singular :) jeg / du / han synger → (plural :) vi / I / de synge .

Conjugation classes

Danish has two weak conjugation classes (with the dental endings -ede, -et versus -te, -t ), the strong conjugation (with ablaut , in the participle also dental ending) and different types of very irregular verbs:

- lave → jeg lavede 'I made', jed har lavet 'I made', jeg tro → troede 'I believed', jeg har troet 'I believed'

- rejse → jeg rejste 'I traveled', jeg har rejst 'I have traveled'

- synge → jeg sang , I sang ' jeg har sunget , I sang', representing more ablautende main groups: drive , drive '→ drev, drevet; bide 'bite' → bed, bidt; krybe 'crawl' → krøb, krøbet; bryde 'break' → brød, brudt; gyde 'pour' → gød, gydt; drikke 'drink' → drakk, drukket; sprække ' to burst' → sprak, sprukket; bære ' to carry' → bar, båret; være ' to be' → var, været; give 'give' → gav, givet; fare ' to drive' → for, faret; gå ' to go' → gikk, gået; with uniform ablaut : falde ' to fall' → faldt, faldet; græde ' to cry' → græd, grædt, hedde ' to be called' → hed, heddet; come 'come' → come, come; løbe ' to run' → løb, løbet

A certain number of verbs belong to the backward verbs that combine vowel changes and dental ending ; the different types are:

lægge , lay '→ lagde, lagt; tælle 'count' → talte, talt; kvæle 'suffocate' → kvalte, kvalt; træde ' to step' → trådte, trådt; sælge 'sell' → follow, follow; sige 'say' → say, say; bring 'bring' → bragt, bragt; gjørde ' to make' → gjorde, gjort; følge , '→ follow fulgte, fulgt .

The verb noun substantivum, the verbs have, gøre, vide and ville as well as the past tense present (the infinitive, present tense, past tense and perfect tense are listed ) show larger and smaller (further) flexivic irregularities :

- Burde 'shall' → jeg bør, jeg burde, jeg har burdet

- gøre 'make' → jeg gør (otherwise the backward verb, see above)

- have 'have' → jed har, jeg havde, jed har haft

- kunne 'can' → any can, any can, any can have

- måtte 'must; may '→ jed må, jeg måtte, jeg har måttet

- skulle 'shall; become '→ everyone is scal, everyone is skull, everyone is skullet

- turde 'dare' → jeg tør, jeg turde, jed har turdet

- være 'sein' → jed er (otherwise the strong verb, see above)

- vide ' to know' → jeg ved, jeg vidste, jeg har vidst

- ville 'want; become '→ jeg vil, jeg ville, jeg har villet

passive

The passive voice is either formed by adding an -s or with the auxiliary blive (literally: 'to stay') plus the past participle:

- Zebraen jages / bliver jaget af løven 'the zebra was chased by the lion'

- De ventes på søndag 'you are expected on Sunday'

The s -passive is used more often to express a state or a regularity, the circumscribed passive more often when it comes to an action, compare for example:

- Slottet ejes af staten 'The castle is owned by the state' (literally: 'owned by the state')

- Dørene lukkes kl. 7 'the doors close at seven o'clock; the doors are closed at 7 a.m. ', but usually: Dørene bliver lukket nu ' the doors are now closed '.

The s -passive then occurs especially in the infinitive and present tense; In the perfect and past tense it is not possible with all verbs:

- Hun sås ofte i teatret ‚she was often seen in the theater; she was often seen in the theater '

- but: Hun blev væltet af cyklen 'she was thrown off the bike'

The s -passive is also used in Danish to form impersonal constructions:

- The må ikke spises i bussen ‚you are not allowed to eat on the bus; Eating in the bus is prohibited '(literally:' It is not allowed to eat ')

The s -passive then occurs in reciprocal verbs; Here you can still understand that the ending -s originated from a suffused sig ' sich ':

- Vi mødes i tomorrow aften 'we'll meet tomorrow evening'

- Vi skiltes som gode venner 'we parted (divorced) as good friends'

Finally, a number of verbs appear as so-called Deponentia in the s -passive; here, too, the origin of sig 'itself' is often still clear. These are verbs that are formally passive but have an active meaning:

- findes 'find oneself, appear, give': The findes mange dyrearter 'There are many animal species'

- mindes 'remember': Jeg mindes ikke hans tale 'I don't remember his speech'

- synes 'seem': Jeg synes, at det er en god idé 'it seems to me that this is a good idea'

mode

The imperative ends in the root of the word and has only one form: kom! 'Come! come! '.

Old texts have a special plural ending -er: Kommer hid, I Pige smaa! 'Come here, you little girls!' ( N. F. S. Grundtvig ).

A morphologically independent subjunctive only exists in fixed phrases, it ends in -e or, in verbs ending in a vowel, with a zero ending, so it is formally identical to the infinitive. Examples are, for example:

leve Dronningen ' long live the queen', gentlemen være med jer 'the Lord be with you', Gud ske lov 'thank God' (literally: 'God be praised').

Incidentally, it has either been superseded by the indicative or, in the unrealis, has coincided with the indicative of the past tense: hvis jed var rig ... 'if I were rich'.

Sentence structure (syntax)

main clause

The Danish sentence structure is based on the scheme subject + predicate + object , but it is extended in the main clause by a second rule of the verb , as it is also in German. This means that the main clause has a so-called preliminary field and then a preferred position for the finite verb . Apart from the finite verb, all parts of the sentence can be used in advance, but most often the subject. If a part of the sentence is placed in advance, its place in the inside of the sentence remains unoccupied (this also applies to the subject).

The following field scheme , which goes back to the Danish linguist Paul Diderichsen , shows the structure of the Danish main clause using a few examples.

| Apron | finite verb |

subject | Adverb A: sentence adverbial |

infinite verb |

object | Adverb B: kind + manner |

Adverb B: place |

Adverb B: time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeg | læser | ikke | en bog | i park | i dag | |||

| Yeg | scal | ikke | læse | en bog | i park | i dag | ||

| I dag | scal | any | ikke | læse | en bog | i park | ||

| I dag | har | any | ikke | læst | en bog | i park | ||

| Yeg | læser | arc | tavs | i dag | ||||

| Yeg | spiser | altid | en rulle | til frokost | ||||

| Til frokost | spiser | any | en rulle | |||||

| Hvad | hedder | you |

subordinate clause

In the subordinate clause, the finite verb is usually further inside the sentence, namely together with the position in which infinite verb forms occur in the main clause. In contrast to the main clause, it then follows after the subject and the sentence adverbial:

(Christian svarede, ...)

| Binding field | subject | Adverb A: sentence adverbial |

finite verb |

infinite verb |

Object (s) | Adverb B: place |

Adverb B: time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at | han | ikke | ville | køre | til byen | ||

| at | han | snart | kunne | Fashion | going | på torvet | |

| at | han | ikke | ville | give | going gaver | to jul |

In a few cases, however, the main clause form, i.e. a second sentence, can follow the conjunction at . For more details see under V2 position # Second verb clauses as subordinate clauses .

ask

If you have questions, the sentence has the following structure:

- Predicate + subject + object

| Hedder you Christian? | Is your name christian |

Questions that cannot be answered with “yes” or “no” are preceded by a question word. In this case, the record has the following structure:

- Question word + predicate + subject (+ object)

| Hvad hedder you? | What is your name? |

Language example

Universal Declaration of Human Rights , Article 1:

- All mennesker født frie og lige i værdighed and rettigheder. The front panel and the control panel, and the door handle mod change in the transmitter cables.

- All people are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should meet one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

- Danish spelling reform of 1948 (with the spelling rules for lower case)

- Dansk Sprognævn (Danish Language Commission)

- List of Danish-speaking writers

literature

The Danish Central Library for South Schleswig contains the largest collection of Danish titles in Germany.

Linguistic introduction

- Kurt Braunmüller: An overview of the Scandinavian languages . Francke, Tuebingen. 3rd, updated and expanded edition 2007 (UTB 1635), ISBN 978-3-8252-1635-1 , pp. 86-133.

- Hartmut Haberland: Danish. In: Ekkehard König, Johan van der Auwera (Ed.): The Germanic Languages. Routledge, London / New York 1994, pp. 1994, ISBN 978-0-415-05768-4 , pp. 313-348.

- Hartmut Haberland: Danish . In: Ulrich Ammon, Harald Haarmann (ed.): Wieser Encyclopedia of the Languages of the European West, Volume 1. Wiesner, Klagenfurt 2008, ISBN 978-3-85129-795-9 , pp. 131–153.

History of the Danish language

- Peter Skautrup: Det danske sprogs historie. Vol. 1–4, Copenhagen 1944–1968 (reprinted unchanged 1968) and 1 register volume, Copenhagen 1970.

- Johannes Brøndum-Nielsen: Gammeldansk grammar i sproghistorisk Fremstilling. Volumes I – VIII Copenhagen 1928–1973; Volumes I – II 2nd, revised edition 1950/57.

Textbooks

- Marlene Hastenplug: Langenscheidt's practical Danish language course. Langenscheidt Verlag, Munich / Berlin 2009. ISBN 978-3-468-80361-1 .

- Vi snakkes ved. Danish course for adults . Hueber, Ismaning 2007.

Grammars

- Robin Allan, Philip Holmes, Tom Lundskær-Nielsen: Danish. A Comprehensive Grammar. London / New York 1995, ISBN 0-415-08206-4 .

- Åge Hansen: Modern Dansk. Vol. 1–3 Copenhagen 1967.

Basic grammars:

- Christian Becker-Christensen, Peter Widell: Politics Nudansk Grammar . Gyldendal, Copenhagen 4th edition 2003, ISBN 87-567-7152-5 . (Important sections such as word order are missing.)

- Barbara Fischer-Hansen, Ann Kledal: Grammatikken. Håndbog i dansk grammar for udlændinge. Special-pædagogisk forlag, Copenhagen 1998.

Syntax:

- Kristian Mikkelsen: Dansk Ordföjningslære. Copenhagen 1911 (reprinted Copenhagen 1975).

Dictionaries

Danish – Danish

- Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab (ed.): Ordbog over det danske Sprog Vol. 1–28. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1918-1956, Supplementbind 1-5. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1992-2005, ISBN 87-00-23301-3 . Around 200,000 keywords with job references. The vocabulary covers the period from 1700–1950. Available on the Internet at http://www.endung.dk/ods or http://www.dsl.dk/ .

- Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab (ed.): Den Danske Ordbog . 6 volumes, Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2003–2005, ISBN 87-02-02401-2 . Is to be understood as a continuation of the aforementioned ODS. Available on the Internet at http://endet.dk/ddo .

- Christian Becker-Christensen u. a .: Politics nudansk ordbog. Politics Forlag, Copenhagen, 19th edition 2005, (approx. 60,000 headwords with CD-ROM for Windows 2000 and Windows XP), ISBN 87-567-6504-5 . Is considered a standard work.

- Christian Becker-Christensen u. a .: Politics nudansk ordbog med etymologi. Politics Forlag, Copenhagen 3rd ed. 2005, 2 vol. (Approx. 60,000 headwords with etymology; spelling rules (Dansk Sprognævn). CD-ROM for Windows 2000 and XP, ISBN 87-567-6505-3 . Vocabulary identical to Politikens nudansk ordbog ).

- Politics Retskrivningsordbog + CD-ROM. Politics Forlag, Copenhagen 1st edition 2001, ISBN 978-87-567-6455-1 . (Spelling dictionary, 80,000 headwords + CD-ROM for Windows 98/2000, ME, NT). Official spelling dictionary established by “Dansk Sprognævn” (“The Danish Duden”).

- Dansk Sprognævn (ed.): Retskrivningsordbogen . Alinea Aschehoug, Copenhagen 3rd edition 2006 + CD-ROM. ISBN 87-23-01047-9 . The official book of Danish spelling ("Der Danish Duden"), largely identical to the spelling books published by Politiken, Gad and Gyldendal publishers. About 85,000 keywords. Internet version at http://www.dsn.dk/ .

Danish – German

- Henrik Bergstrøm-Nielsen et al. a .: Dansk-tysk ordbog . Munksgaard, Copenhagen, 2nd edition 1996, ISBN 87-16-10845-0 . Currently the largest and most comprehensive Danish-German dictionary with around 100,000 headwords. As is customary in Danish-German lexicography, the Danish headwords are given without gender, conjugation or declension. No pronunciation information.

- Jens Erik Mogensen u. a .: Dansk-Tysk Ordbog . Gyldendal, Copenhagen, 11th edition 1999, ISBN 87-00-31758-6 . About 73,000 keywords. (See note on previous work).

German – Danish

- Bergstrøm-Nielsen u. a .: Tysk-Dansk Ordbog - Stor. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2005, ISBN 87-00-40058-0 . Currently the most extensive German-Danish dictionary with approx. 153,000 headwords, which replaces the planned but never published Tysk-Dansk dictionary by the same author (Munksgaard, see above).

Danish – German / German – Danish

- Langenscheidt editors (Hrsg.): Pocket dictionary Danish. Danish-German. German-Danish . Langenscheidt, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-468-11103-7 . Around 40,000 keywords each with grammatical information. Pronunciation information. Very good tool for beginners and advanced users.

- Dansk-Tysk / Tysk-Dansk Ordbog, CD-ROM. From Windows 98 and Microsoft Word 95. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2003, ISBN 87-02-01495-5 .

Special dictionaries

- Niels Åge Nielsen: Dansk Etymologisk Ordbog. Ordenes history . Gyldendal, Copenhagen 5th edition 2004, ISBN 87-02-03554-5 . 13,000 keywords.

- Ole Lauridsen et al. a .: Dansk-Tysk Erhvervsordbog . Gyldendal, Copenhagen 2nd edition 2005, ISBN 87-02-03718-1 . 8300 keywords.

- Wilhelm Gubba: Dansk-Tysk Juridisk Ordbog . Gyldendal, Copenhagen 4th edition 2005, ISBN 87-02-03986-9 .

- Aage Hansen et al. a. (Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab ed.): Holberg-ordbog. Ordbog over Ludvig Holbergs sprog . 5 volumes, Reitzel, Copenhagen 1981–1988, ISBN 87-7421-278-8 . (The special dictionary on the language of Ludvig Holberg and on Danish in the 18th century.)

Pronunciation dictionaries

- Lars Brink, Jørn Lund u. a .: The store Danske Udtaleordbog. Munksgaard, Copenhagen 1991, ISBN 87-16-06649-9 . Approx. 45,000 keywords. Only available as an antiquarian. Leading scientific work.

- Peter Molbæk Hansen: Udtaleordbog. Dansk udtale. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1990, ISBN 87-00-77942-3 . Approx. 41,000 keywords.

Web links

Dictionaries

- The Danske Ordbog dictionary of the Danish language after 1950

- Retskrivningsordbogen Danish spelling

- sproget.dk metasearch via Retskrivningsordbogen, Den Danske Ordbog and Ordbog over det danske Sprog as well as other definitions

- The Danske Online Ordbog

Linguistic history dictionaries

- Ordbog over det Danske Sprog Dictionary of the Danish language 1700–1950

- Renæssancens sprog i Danmark The Danish language of the Renaissance

Corpora

Links to learn Danish

- Podcast feed of the weekly program Sproghjørnet on the Danish language

- Subject portal Danish of the Institute for Quality Assurance in Schools Schleswig-Holstein

- German-Danish Teachers' Association / Dansk-Tysk Lærerforening

- GrammarExplorer Danish (German and English)

- IRSAM German-Danish language project

- dansk.nu

- danskopgaver.dk

- Danish as a Foreign Language - Link Collection

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sprog. In: norden.org. Nordic Council , accessed 24 April 2014 (Danish).

- ↑ EUROPA - Education and Training - Europa - Regional and minority languages - Euromosaïc study. October 14, 2007, archived from the original on October 14, 2007 ; accessed on February 28, 2015 .

- ↑ Landtag Schleswig-Holstein ( Memento from July 3, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sources: Society for Threatened Peoples, Institute for Border Region Research, University of Southern Denmark

- ^ University of Tromsø ( Memento from March 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Bund Deutscher Nordschleswiger , 2008

- ↑ Denmark.dk: The German Minority in Denmark

- ↑ The Store Danske Encyclopædi, Volume 4, Copenhagen 1996

- ↑ Christel Stolz: Besides German: The autochthonous minority and regional languages of Germany, Bochum 2009, page 18

- ↑ Niels Åge Nielsen: Dansk dialektantologi, I Østdansk og Omal . Hernov, Odense 1978, ISBN 87-7215-623-6 , pp. 9, 15 .

- ^ Bengt Pamp: Svenska dialekter . Natur och Kultur, Stockholm 1978, ISBN 91-27-00344-2 , p. 76 .

- ↑ a b c Allan Karker: "Sproghistorisk oversigt". In: Nudansk Ordbog (1974), p. 17 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Oskar Bandle : The structure of the North Germanic. Basel / Stuttgart 1973 (since then reissued); Arne Torp: Nordiske språk i nordisk and germansk perspective. Oslo 1998.

- ↑ Peter Skautrup: Det danske sprogs historie .

- ^ Karen Margrethe Pedersen: Dansk Sprog i Sydslesvig . tape 1 . Institut for grænseregionsforskning, Aabenraa 2000, ISBN 87-90163-90-7 , p. 225 ff .

- ↑ Kurt Braunmüller: The Scandinavian Languages at a Glance (2007), p. 86 ff.

- ↑ Karl Nielsen Bock: Low German on Danish substrate. Studies on the dialect geography of Southeast Schleswig.

- ↑ Hans Volz : Martin Luther's German Bible, Hamburg 1978, p. 244

- ↑ Middle Low German loanwords in the Scandinavian languages

- ↑ a b The word component tyve in the last-mentioned example goes back to the old Danish tiughu 'tens' and, although ultimately the same origin, should not be confused with tyve 'twenty'; see. Niels Åge Nielsen: Dansk Etymologisk Ordbog. Ordenes history. Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1966, with numerous new editions.

- ↑ http://sproget.dk/raad-og-gler/artikler-mv/svarbase/SV00000047/?exact_terms=tal&inexact_terms=talt,talendes,taltes,tallet,tals,tales,taler,talte,tale,tallets,talende, talts, tallenes, tallene

- ^ Robin Allan, Philip Holmes, Tom Lundskær-Nielsen: Danish. A Comparative Grammar. Routledge, London / New York 1995, p. 128.