North Schleswig

The part of the former Duchy of Schleswig that has belonged to the Kingdom of Denmark since 1920 is referred to as Nordschleswig ( Danish : Nordslesvig ) . The part that remained with Germany is called Südschleswig .

From the Viking Age to 1864, the Schleswig region was connected to the Danish crown in different ways (initially directly, later as a fiefdom ). From 1867 to 1920, Schleswig was part of the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein . In 1920 Northern Schleswig came to Denmark. From 1970 until the regional reform in 2007 , the area of North Schleswig corresponded to that of the Sønderjylland district . It covers an area of around 5794 km².

geography

North Schleswig stretches from the German-Danish border to the Kongeå ( German Königsau ), in the west to Ribe ( German Ripen ) and in the east to the Little Belt south of Kolding .

The Sønderjyllands Amt, which was opened in the Syddanmark region on January 1, 2007, was geographically identical to Nordschleswig. In Danish, the term Sønderjylland is more common for North Schleswig, even if the term Sønderjylland can in principle be applied to the entire Schleswig region. After 1920, the term sønderjyske landsdele (South Jutland parts of the country) was widespread for North Schleswig . Until the German-Danish War of 1864, the former duchy also included a few parishes up to the coast of the Koldingfjord (all the way to the city limits of Kolding), the Baltic island of Ærø , and - in the Middle Ages - Ripen and its surrounding area south of the Königsau. These areas were added to Denmark after 1864 as part of a land exchange, which in return renounced royal enclaves in Schleswig.

The place names have both a Danish and a German version (see also list of Schleswig place names )

To promote cross-border cooperation, the Sønderjylland-Schleswig region was founded in 1997 . On the German side, the districts of North Friesland , Schleswig-Flensburg , the city of Flensburg and, on the Danish side, the Syddanmark region and the four previous municipalities of Nordschleswigs Tønder Kommune , Aabenraa Kommune , Haderslev Kommune and Sønderborg Kommune work together.

population

Around 250,000 people live in North Schleswig. The German minority , which calls itself the German ethnic group or German North Schleswig-Holstein , makes up around 6 to 10 percent of the population today, around 10,000 to 20,000 people. In the referendum in 1920, around 25,329 residents (24.98%) voted for Germany. Before the Second World War, their size was given as up to 30,000; in the meantime, as a result of assimilation and migration , it has decreased to its present level.

languages

In North Schleswig, in addition to Standard Danish and South Jutian ( Sønderjysk ), German is also spoken, the latter mostly in the form of North Schleswig German as a variant of High German influenced by Danish (or contact variety to Danish). Most Germans from Northern Schleswig are able to speak both German and Danish. About two thirds of the Germans in North Schleswig use Danish as a colloquial language. However, German is still the cultural language of the German minority.

In addition to the two high-level languages, the characteristic Sønderjysk has been preserved mainly in the countryside and is spoken by almost all members of the German ethnic group, around two thirds of whom are the home language, and by many Danes. Differences in the use of the respective language are more evident in the school and standard language; German is preferred for official occasions (e.g. meetings) of the German ethnic group.

The use of Low German (Nordschleswiger Platt) was relatively low in Nordschleswig, and today it is only used by a few families as a colloquial language. In Nordschleswiger , the daily newspaper of the German minority, there is a small daily column on Nordschleswiger Platt.

economy

The region is mainly characterized by agriculture and tourism . Tourism plays an important role on the west coast, but also partly on the east coast. In addition to medium-sized companies, some large companies have their headquarters in the region, namely Danfoss in Nordborg ( German Norburg ), Ecco in Bredebro or Gram in Vojens ( German Woyens ).

media

In Nordschleswig, JydskeVestkysten and Der Nordschleswiger , a daily newspaper each in Danish and German, appear. The former has its central editorial office in Esbjerg and appears in several local editions in the region. In addition to the daily newspapers, Danmarks Radio produces a regional program for the region with Radio Syd .

For some years now, there has also been a private radio program called Radio Mojn . On this, as well as on Radio 700 and Radio Flensburg , German-language news updated three times a day, which is designed by Nordschleswiger , is shown.

Regional news programs and some other TV Syd productions are broadcast on TV2 .

politics

In North Schleswig there is the Schleswig Party (SP) in addition to the nationwide Danish parties . The SP acts as a regional party and represents the interests of the German minority in North Schleswig. SP representatives were elected in three of the four municipalities of North Schleswig, and in the last one (Haderslev, German Hadersleben ), a mandate without voting rights was guaranteed by a special regulation. (See: minority voting rights )

After the regional reform, with which the Sønderjyllands Amt in the Syddanmark region was opened on January 1st 2007 , the SP is no longer represented at regional level.

The German minority is represented in the contact committee for the German minority at the government and the Folketing in Copenhagen, where it also operates a permanent secretariat . In Kiel , the committee for questions of the German minority maintains contact with the Schleswig-Holstein state parliament . The BDN is represented in both bodies.

history

North Schleswig was part of the Duchy of Schleswig . After the referendums of 1920, this part of Schleswig was assigned to Denmark.

Schleswig or South Jutland was still part of the Kingdom of Denmark in the early Middle Ages; but as early as the 12th century it developed into a Jarltum and later a Duchy , which, politically and economically, leaned heavily on the neighboring Holstein . The Holstein influence in Schleswig was particularly evident in the marriage of King Abel to Mechthild von Holstein , daughter of Count Adolf IV of Holstein , in 1237 and from 1375 to 1459 during the reign of the Schauenburgers , who were also princes of Holstein. From 1460 the Danish king was again Duke of Schleswig, the duchy was accordingly in a personal union with Denmark. In terms of constitutional law, Schleswig developed as a fiefdom of Denmark. At times, the king's younger brothers received shares in the duchies to compensate for them ( secondary school ), for example when the country was divided in 1544, Gottorf shares in the duchies were created. In the royal parts of Schleswig, the Danish king ruled both as a duke (vassal) and as a king (feudal lord), while in the remaining parts he was exclusively feudal lord. For the areas with aristocratic or ecclesiastical goods there were also jointly governed shares. There was a common government for matters affecting the whole of the duchies. After the Northern War in 1721, the ducal shares fell back to the king.

In Schleswig, Jutian law (Jyske Lov) still applied until it was replaced by the Civil Code in 1900 . The Danish law (Danske Lov), introduced in Denmark in 1683, only applied in the royal enclaves (such as in the south of the island of Rømø). Otherwise, the jurisdiction of the Danish empire with the nationwide higher courts and the legislation of the Danehof was valid in Schleswig until the reign of King Frederick I (1523-1533). The law of Denmark has been in effect in North Schleswig since 1920 .

19th century

In the 19th century, attempts to completely separate Schleswig and Holstein from Denmark and integrate it into a German federal state, and to incorporate the duchy into the Kingdom of Denmark, led to national and constitutional disputes. Ultimately, the differences culminated in the Schleswig-Holstein Uprising and the German-Danish War (1864).

In the London Protocol of 1852, the major European powers stipulated that the Danish King was not allowed to separate Schleswig and Holstein. Since Holstein, unlike Schleswig, was a member state of the German Confederation , this effectively forbade the planned unification of Schleswig with Denmark.

German time after 1864

After the decision had almost been made in the German-Danish War, negotiations about a possible partition of Schleswig took place at the London Conference (1864) . The Prussian side offered the Aabenraa-Tondern border, while the Danish side offered the Tönning-Danewerk-Eckernförde border. Compromise proposals on the part of Great Britain and France, such as a division at the level of the Schlei or a line from Gelting to Husum, were not approved by the warring parties. Then the war flared up again and Prussia conquered Alsen and, shortly afterwards, all of Jutland with Austria . In the Peace of Vienna (1864) Denmark had to cede the whole Duchy of Schleswig and the Duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg to Prussia and Austria, which both administered it together. Only smaller areas in the north remained against a land exchange with the royal enclaves with Denmark. In the Peace of Prague after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the three duchies were finally assigned to Prussia, which formed the province of Schleswig-Holstein from them. At the pressure of the French Emperor Napoleon III. a special provision was inserted into the contract in paragraph 5, after "the population of the northern districts of Schleswig, if they indicate by free vote the wish to be united with Denmark, should be ceded to Denmark". This paragraph provided hope for the Danish majority in Northern Schleswig; however, it was mutually canceled in 1879 by the actual contracting parties, Prussia and Austria.

National conflicts continued during the imperial era. The Danish part of the population demanded cultural freedom and never gave up the idea of a border revision. Attempts by the Prussian authorities (especially under the senior president Ernst Matthias von Köller 1897–1901) to strengthen Germanness in the part of the country did not have a resounding success, but fueled the conflict further. In 1888, German became the sole language of instruction in all schools with the exception of four hours of religious instruction. After 1896, the Prussian government purposefully bought up farms and converted them into so-called state domain farms (Danish: Domænegårde ), which were occupied by German tenants. Around 60,000 Danish Schleswig emigrants by 1900, of which around 40,000–45,000 went overseas. About 25,000 Schleswiger chose as optants the possibility Danish nationality maintain. The resulting problem of the citizenship of the children of Danish optants was resolved in 1907 in the so-called Optanten contract . Under the repressive language and cultural policy of Prussia, the Danish minority increasingly began to organize, for example with the establishment of the North Schleswig voters' association. In the meantime, there was a slight economic upswing in North Schleswig, and industrialization reached at least the eastern district towns. However, North Schleswig was away from the main traffic flows and its development was hindered by the fact that the previously relatively permeable border between the actual Kingdom of Denmark and the Duchy of Schleswig was now deprived of a border between two national states and the region of its northern hinterland. North Schleswig fell more and more behind, not only compared to Holstein , but also to eastern Jutland. The cities of Hadersleben and Aabenraa , which have dominated the northern hinterland so far, have been significantly overtaken by smaller cities such as Kolding or Vejle in terms of economic power and population and are still in their economic shadow.

5000 young people from northern Schleswig died on the fronts during the four years of the First World War . The part of the country itself did not become a theater of war; but for fear of a British invasion over neutral Denmark, the bunker belt of the security position north was created . At the end of the war, this part of the country, like large parts of Europe, was ruined by the war economy.

Referendum

The representative of the Danish ethnic group in Schleswig in the German Reichstag, Hans Peter Hanssen , received from the new Reich government the concession in October 1918 that the Schleswig question should be decided on the right of the peoples to self-determination . Although the term “Nordschleswig” was quite common, there was no precisely defined space before the vote. After the First World War, Articles 109 to 114 of the Versailles Treaty stipulated that the people of Schleswig could decide for themselves the demarcation between the German Empire and Denmark in a referendum .

The plebiscite was held in two voting zones. The modalities of the vote, however, led to controversy: the boundaries were not - as determined in the Versailles Treaty - set by mutual agreement and also not by the population of Schleswig, but by Denmark, which in the case of the Allied Commission both the division into voting zones defined by Denmark and different modalities the vote in these prevailed. For example, a northern zone (1st voting zone), in which voting took place en bloc as a whole, and a southern zone (2nd voting zone), in which voting took place afterwards, was set up, with the aim of subsequently defining the border according to the To move results further.

All persons born before January 1, 1900, who either came from the plebiscite area or had lived there since 1900, or who had lived there before 1900, had been expelled by the Danish (until 1864) or German authorities (until 1914), were entitled to vote. This set in motion corresponding activities of both ethnic groups to mobilize compatriots outside the voting zones.

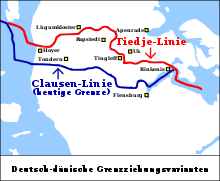

The first voting zone comprised what is now North Schleswig, defined by the " Clausen Line " south of Tønder ( German Tondern ) and north of Flensburg , which marks today's German-Danish border.

By drawing the border, the districts of Tondern and Flensburg were cut up. The aim of the representatives of Denmark - besides H. V. Clausen especially H. P. Hanssen - was to create as large a coherent area as possible, which was also functional in terms of economy and traffic routes. Although the Clausen line corresponded to the line between German and Danish church language, as it ran in the middle of the 19th century, it did not separate language and conviction areas at the time of the vote. In order not to risk a possible electoral defeat in the northern zone by including the populous, mostly German-minded city of Flensburg, the voting border was placed directly north of Flensburg, which even led to protests from the Danish side, as the city was the cultural and economic center of the entire Schleswig. In the Reichstag elections in 1867, the city had shown a Danish majority, in the Reichstag elections in 1907 and 1912 there were already only 13.5% and 13.7% for the entire constituency of Aabenraa-Flensburg, that is, combined with heavily Danish-oriented areas the Danish party. H. P. Hanssen defended his view that Flensburg belongs to North Schleswig, “but not to the Danish North Schleswig” - as the result of the vote with 75% for Germany in the city rightly showed.

In the vote in the 1st zone on February 10, 1920, 74.9 percent of the electorate voted for unification with Denmark.

In the three northern districts of Hadersleben, Aabenraa and Sønderburg, the results for Germany with shares of 16%, 32% and 23% were relatively clear, even though the cities of Aabenraa with 55% and Sønderborg with 56% voted mostly German, the patch of Augustenburg almost 50% and the city of Hadersleben still had almost 40% German votes. Here the rural areas dominated over the cities.

In the northern parts of the two border districts of Tondern and Flensburg, which are also assigned to Zone I, with over 40% votes for Germany and almost 60% for Denmark, however, the situation was almost balanced, such as the patch of Lügumkloster with 49% to 51%. shows, and with the city of Tondern with 77%, the area of Hoyer with 73% and the surrounding area with 70% German votes, there was a zone that overall was mostly German.

These areas, located directly on the dividing line between voting zones I and II, which had voted for Germany by the majority, formed contiguous areas in the south-west around Tondern and south-east north of Flensburg. They were referred to as Tiedje belts because, according to the proposal of the German historian Johannes Tiedje , they should have been allocated to Germany.

The en bloc vote, however, led to the fact that in addition to the cities with a German majority, which were isolated in an otherwise largely Danish-speaking area, this clearly German-minded area around Tondern also came to Denmark and was cut off from its surrounding area.

South of the Clausen Line, in the 2nd voting zone with Glücksburg, Flensburg, Niebüll, Sylt, Föhr and Amrum, 80.2 percent of those entitled to vote voted to remain with the German Reich; the proportion of Danish votes in the west coast districts of Tondern and Husum-Nord was 10–12%, in the city of Flensburg, which has grown rapidly since 1871, and the district of Flensburg at 25% and 17%.

Assignment to Denmark

The overall result of the vote was relatively clear, if not as clear as the result of the subsequent southern vote; But there were still protests on both sides, especially on the part of the German-minded people in the Tiedje belt. Nevertheless, a revision of the division of territory was not considered based on the results of the vote: On June 15, 1920, Northern Schleswig was integrated into the Kingdom of Denmark as "the southern Jutland parts" (de sønderjyske Landsdele) .

In Denmark, the incorporation of North Schleswig is often referred to as “reunification”.

Under international law, Denmark was granted sovereignty rights over North Schleswig in the Paris Treaty of July 5, 1920 from the victorious Allied powers, which referred to the agreement on the border between Germany and Denmark on June 15.

literature

- Axel Henningsen : North Schleswig . Karl Wachholtz Verlag, Neumünster.

- North Schleswig . Husum printing and publishing company.

- Gerd Stolz, Günter Weitling : North Schleswig - Landscape, People, Culture , 1995 edition. Husum Printing and Publishing Company, ISBN 3-88042-726-7 .

- Gerd Stolz, Günter Weitling: North Schleswig - Landscape, People, Culture , 2005 edition. Husum Printing and Publishing Company, ISBN 3-89876-197-5 .

- From a life in two cultures - picture of a border landscape. Christian Wolff Verlag, Flensburg.

- Hans Peter Johannsen: Seven Schleswig Decades - Books, Encounters, Letters. Schleswiger Druck- und Verlagshaus, 1978, ISBN 3-88242-031-6 .

- Jan Schlürmann : The meeting houses of the Danish minority in Schleswig 1864–1920. In: Peter Haslinger, Heidi Hein-Kircher , Rudolf Jaworski (eds.): Heimstätten der Nation - East Central European Association and Society Houses in a Transnational Comparison (= Conferences on East Central Europe Research, 32). Marburg 2013, pp. 115-136.

- Florian Greßhake: Germany as a problem for Denmark: The material cultural heritage of the border region Sønderjylland - Schleswig since 1864 . V & R unipress, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8471-0081-2 ( GoogleBooks ).

Web links

- Institutions of the German minority

- Region of Sønderjylland / Schleswig

- The Nordschleswiger - daily newspaper of the German minority

- Deutsches Historisches Museum - Collective Memory ( Memento from February 20, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl Strupp : Dictionary of international law and diplomacy. 3 volumes. 1924-1929, p. 118.

- ↑ Working Group of German Minorities in the Federal Union of European Nationalities ( Memento of December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Ulrich Ammon: The position of the German language in the world. Essen 1991, p. 306.

- ↑ Museum Sønderborg Slot: Nye grænser - nye mindretal.

- ^ Schleswig Party: History of the Schleswig Party.

- ↑ Torben Mayer: The German minority in North Schleswig and the coming to terms with one's own National Socialist past.

- ^ Elin Fredsted: Languages and Cultures in Contact - German and Danish minorities in Sønderjylland / Schleswig. In: Christel Stolz: In addition to German: the autochthonous minority and regional languages of Germany. Bochum 2009, p. 18.

- ↑ Steffen Höder: North Schleswig German. ( Memento from December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Working Group of German Minorities in the Federal Union of European Nationalities ( Memento of December 8, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Danske Encyclopædi store. Volume 4. København 1996.

- ^ Ferdinand Selberg: The German ethnic group in North Schleswig. In: pogrom 179 (Journal of the Society for Threatened Peoples ), October / November 1994.

- ↑ Mechtilde. Gyldendal Store Danske, accessed November 28, 2015 .

- ^ Robert Bohn: Danish history. CH Beck, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-406-44762-7 , p. 96.

- ^ Karl N. Bock: Middle Low German and today's Low German in the former Duchy of Schleswig . Copenhagen 1948, p. 42/43 .

- ^ Article V , Society for Schleswig-Holstein History

- ^ Schleswig-Holstein History Society: North Schleswig

- ↑ Historisk Samfund for Sønderjylland: Sønderjylland A-Å , Aabenraa 2011, page 80/81

- ↑ Vejen municipality: Tyske domænegårde i Sønderjylland

- ↑ Record of the domain farms in northern Schleswig

- ↑ Jacob Munkholm Jensen: Dengang jeg drog af sted-danske immigranter i the amerikanske borgerkrig. København 2012, pp. 46/47.

- ↑ Jan Asmussen: We were like brothers , Hamburg 2000, sider 361/362

- ^ Inge Adriansen: Places of remembrance of German-Danish history. In Bea Lundt (Ed.): Northern Lights. Historical awareness and historical myths north of the Elbe. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-412-10303-9 , p. 402.

- ^ Treaty Between the Principal Allied Powers and Denmark Relative to Slesvig. In: The American Journal of International Law , Vol. 17, No. 1, Supplements: Official Documents (Jan. 1923), pp. 42–45 (English), accessed on July 4, 2011.

Coordinates: 54 ° 51 ′ 21.1 ″ N , 9 ° 22 ′ 2.5 ″ E